The tiny Chapel of St Edmund on Priory Road, sometimes in 19th century books referred to as the Church of St John, has had a chequered history. It is believed that a ‘Cemetery of the Poor’ was established in 1131 by the Priory of St Martin’s on ground between the Priory (now Dover College) and the Maison Dieu. The latter, a religious hospice, particularly administered to pilgrims going to and from Canterbury Cathedral where there was a shrine to Thomas Becket Archbishop of Canterbury (1162-1170). Many of the pilgrims were sick and those who died and had no money were buried in the poor peoples’ cemetery. This was established facing the monastery walls for which the small chapel was built.

Edmund Rich (1175-1240) was born in Abingdon, Berkshire, educated at Oxford University where he later taught logic (1219-1226) and was appointed a canon of Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire in 1222. He quickly gained fame as a preacher in England and France and was commissioned by Pope Gregory IX (1227-1241) to preach, throughout England, in support of the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229). Following the death of the Archbishop of Canterbury (1206-1228) Stephen Langton (c.1150- 1228), Pope Gregory appointed Richard le Grant, to the See in 1229 and he held the office until his death in 1231. By then, the Archbishop had fallen foul of Henry III (1216-1272) over the Clare estates in Tonbridge, Kent. The King was supporting Hubert de Burgh, (c.1160–1243), his Chief Justicular, who was also the 1st Earl of Kent, Constable of Dover Castle, the benefactor of Dover’s Maison Dieu. Not long after, in 1233, De Burgh also fell foul of the King and in 1233, was imprisoned in Devizes Castle, Wiltshire.

On the death of Archbishop Richard le Grant, four men were put forward to become the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first was rejected outright by both Pope Gregory and King Henry while the other three, although supported by the King, had their election quashed by the Pope! In the end, in 1234, Pope Gregory put forward Edmund Rich and at first Henry agreed. However, that year he married Eleanor of Provence (1223-1291) and the new Queen insisted that high offices including the See of Canterbury should go to her own kinsmen. Pope Gregory refused to be over-ruled.

As the new Archbishop Edmund instituted reforms in the ecclesiastical courts, monasteries and among the clergy but, not surprisingly, these reforms did not go down well with some. They complained to both the Pope and the King and the Pope ordered 300 English benefices to be assigned to Rome. Although Edmund was physically far from well he decided to go to Rome to plead his case before the Curia (the administrative unit of the Holy See). To accompany him, the Archbishop called upon his protégé and Chancellor, Richard de la Wyche (1197-1253).

Richard, born in Droitwich (then called Wyche), Worcestershire, had been one of Edmund’s students at Oxford. He then went on to study at the Universities of Paris and Bologna, Italy, where he read Canon Law. On returning to Oxford in 1235, Richard was appointed Chancellor and soon after Edmund asked him to become the Chancellor to the Province of Canterbury. In this role Richard would have been responsible for administration and the preparation of documents etc. of the See.

The late autumn weather in 1240 was treacherous and took its toll on Edmund’s health such that when they arrived at the Cistercian Monastery of Pontigny, near Paris, the feeble Edmund became sick. They decided it would be best to return to England but Edmund’s health continued to deteriorate and a few days later on 16 November 1240 Edmund died. He was buried in the Great White Church, Pontigny.

Subsequent to the death of Edmund, Richard decided to follow his beloved master’s calling and to devote the remaining years of his life to the priesthood joining the Dominican Order. St. Dominic (1170-1221) founded the Order in 1215, the monks been known as the Black Friars due to the black cloaks they wore over their white habits. Unlike, other monastic institutions, Dominicans did not stipulate as belonging to a designated House. In consequence the friars could, and were, sent anywhere and at any time, to preach the Christian doctrine. Because all the other Orders stipulated that preaching was the prerogative of bishops and their delegates, the Dominicans were, at best, frowned upon by the other monastic institutions. Under the Dominicans, Richard studied theology in Orléans, France, for two years and was Ordained. Following Ordination, Richard returned to England and in 1243 he was appointed the Rector of Charing, Kent.

On 16 September 1243 Boniface of Savoy (c. 1207- 1270), the uncle of Queen Eleanor, was nominated as the Archbishop of Canterbury and this was confirmed by Pope Innocent IV (1243-1254). Boniface arrived in England the following year but found that the Canterbury See was in debt by 22,000 marks and immediately instituted sweeping financial stringency on both tenants and clergy. Two years later, in 1245, the First General Council of Lyon was held when the Pope consecrated Boniface into office. He was enthroned when he returned to England in 1249. While in Lyon, in 1246, Boniface put forward the case for the canonisation of Edmund of Abingdon and offered Richard his former post, that of the Chancellor to the Province of Canterbury.

Meanwhile, in February 1244, Ralph Neville the Bishop of Chichester died. He was also the Lord Chancellor, the Keeper of the Great Seal, the Chief Royal Chaplain and adviser to Henry in both spiritual and temporal matters. The King’s favoured candidate was Robert Passelewe (d 1252) the Archdeacon of Lewes who had recently regained favour of the King as an adherent of Peter des Roches (d 1238). Roches had been appointed the Chief Justicular of England, Hubert de Burgh’s former post. And he had also been given de Burgh’s manors, some of which he had passed on to Passelewe. Archbishop Boniface, on the other hand, favoured his Chancellor, Richard de Wych. Pope Innocent had the final choice and he declared Passelewe’s candidacy void while supporting the Archbishop’s choice by confirming Richard’s election.

Henry III was so angry that he refused to give up properties and revenues of the See of Chichester and banned anyone helping or offering hospitality to Richard. Although Pope Innocent wrote to the King on Richard’s behalf, Henry refused to accede. Thus, Richard was forced to wander around his own diocese, dependent on charity, in return for which he showed folk how to make the most of their farmland. At the same time, Richard sought redress through Henry’s Royal Court but to no avail, while letters from the Pope to the King on Richard’s behalf, made no impression. Eventually, in 1247, Pope Innocent threatened to excommunicate Henry if he did not accept Richard as the Bishop of Chichester and the King was forced to acquiesce.

The Holy Land Crusades (1095-1291) were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the incumbent Pope with the intention of permanently recovering Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Islamic rule. In 1244 Jerusalem was in the hands of the Muslims and Pope Innocent IV advocated the need for another crusade. However, he was heavily caught up in a power struggle against the Holy Roman Empire’s Frederick II (1220-1250), as well rebellions in the Baltic along with Mongol incursions. The French King Louis IX (1226-1270), a devout Christian, made the decision to lead what became known as the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254). Given Pope Innocent’s blessing, his aim was to reclaim Jerusalem by attacking Egypt, then the main seat of Islamic power under As-Salih Ayyub (1205-1249). Although Henry III declined to be involved, he did not discourage members of his Court from joining and he even signed a truce promising not to attack French lands during the Crusade!

Initially, the Crusade was a success and following the death of As-Salih Ayyub, Louis felt confident of victory. This did not last long, for the proclamation of the Sultan’s son Al-Muazzam Turanshah (1249-1250) gave the Egyptians renewed impetus. In April 1250 the Crusaders were defeated at EI Mansûra in Egypt and Louis IX and his army were taken into captivity. Although the King was held for a ransom the ongoing power struggle between the Pope and Frederick II continued to dominate European politics, so outside of France, little notice was taken of the plight of Louis and his Crusaders. Then, in December 1250, Frederick died peacefully in bed wearing the habit of a Cistercian monk. His Empire was divided between his sons and he willed that all the lands he had taken from the Church be returned. Thus, the Pope’s attention was able to focus on the plight of the Crusaders and he called on Richard and other bishops to raise funds to pay the ransom of 400,000 livre for Louis IX.

Maison Dieu the religious hospice founded by Hubert de Burgh in 1203, where Richard of Chichester sought refuge.

Richard set out from Chichester in early January 1253 in order to raise money by preaching about the Crusade and the plight of the Crusaders. Wearing a hair-suit and simple open sandals he was well known for his frugal clothes and eating habits. Slowly, he worked his way eastwards along the south coast and although welcomed every where he went, the already cold, wet and windy weather continued to do its worst throughout February and March. Indeed, by late March 1253, when Richard arrived in Dover, there was no sign of spring. Both emaciated and sick he sort refuge at the town’s Maison Dieu, the religious hospice founded by Hubert de Burgh. Under the care of the Master, Michael de Kenebalton, Richard gained a little strength and he was asked by the Brethren to consecrate the nearby, rebuilt, poor people’s cemetery Chapel in honour of St Edmund of Abingdon. This, Richard was more than happy to do.

The dedication ceremony of the Chapel took place on Refreshment Sunday, 30 March 1253, but the next day Richard health rapidly deteriorated and at midnight of 3 April, at the age of 56, he died in the Maison Dieu. Before the Bishop’s body was returned to Chichester Cathedral for burial, his heart was removed, put in a leather pouch and buried in a Cist, or pit, under the Chapel’s altar. On 22 January 1262, 9 years after his death, Richard was canonised at Viterbo, Italy, by Pope Urban IV (1261-1264). As St Edmund’s chapel was the only church in England dedicated to one English Saint by another it quickly became a place of pilgrimage that lasted until Reformation (1529-1536).

During the Reformation the Chapel, the Maison Dieu and the nearby Priory of St Martin’s were surrendered to Henry VIII (1509-1547). The Wellard family, who were of considerable importance in Dover at this and for some time after, built their mansion on the site of the Chapel incorporating it into their dwelling. Reverend John Lyon of St Mary’s Church, Dover, described this in his two volume History of Dover published in 1813.

In the years that followed the mansion was demolished but the Chapel remained and was incorporated into buildings facing the town’s main thoroughfare, Biggin Street. The site of the old Priory became Priory Farm and was bounded by a stone wall, probably the original one that also went around the Chapel’s small cemetery. It is reported that there was a small gate in the corner of this wall, approximately where the Prince Albert pub now stands. This opened onto a path that led to the front of the Priory Farm.

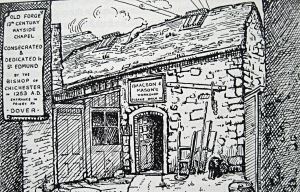

Priory Road was laid in 1872 by which time Fred Turtle, a whitesmith, plumber and electrician, was using the Chapel as a workshop. Mabel Martin captured this in a drawing she made 1939. In 1875, the floor of the adjoining Comet Inn collapsed and to everyone’s surprise, in the debris were found coffins! These roused a great deal of interest and local historian, Reverend S.P. Stretham wrote a description of the Chapel stating that it was still incorporated in the surrounding buildings. He described the Chapel as small – 28 feet long (8.5 metres) and 14 feet broad (4.26 metres) with walls ‘which are fairly intact.’ These, ‘are 2 foot thick (0.6 metres) and built of rubble masonry with Caen stone quoins and dressings.’ Reverend Stretham conjectured that the Chapel belonged to the Priory, the Maison Dieu or the Hospital of St Bartholomew in Buckland.

Reverend Stretham’s speculation was, at best, dismissed as it was generally agreed on the evidence available, that the building was a medieval wayside chapel that was dedicated to St John. It wasn’t until 1932 that anyone dared to contradict that theory but in that year local historian, W J Baker, suggested that it was possibly the Chapel consecrated by St Richard of Chichester in honour of St Edmund of Abingdon in 1253. In January 1935, during the relaying of Priory Road, Professor F M Downey of Oxford University came to Dover and examined the building carefully. At the time Isaacson & Mason were using the building as a forge but the Professor was able to confirmed Mr Baker’s opinion.

On 3 September, World War II (1939-1945) was declared and on 24 August 1943, during heavy shelling, Bricknell’s newsagents and tobacconist shop in Priory Road was wrecked. When the ruins were cleared, St Edmund’s Chapel was seen unattached to surrounding buildings for the first time in four hundred years! For many in Dover this was seen as a message from God and revered. Indeed in 1944, following a request from the Reverend Stanley Cooper, vicar of St Mary’s Church, Borough Engineer, Philip Marchant, proposed to restore the Chapel as a war memorial. With this in mind it became a major feature of the proposed post-war Abercrombie Plan for the future development of Dover.

Much to the surprise of many, in 1953 a memo from the Ministry of Works stated that St Edmund’s Chapel was not an ancient monument and its preservation could not be described as of national importance. At the time the Buckland branch of Toc H – the international Christian Charity movement, occupied the Chapel. They had undertaken some restoration before refurbishing the Chapel as a workshop to make and repair toys as Christmas presents for poor and sick children, assisted by lads from the Borstal on Western Heights. Among other charitable deeds, Toc H collected and chopped wood to give to the elderly poor of the town who had open fires. Throughout their tenure moves were made to have the 1930’s Downey and Baker report that the building was of historic significance recognised and for it to be listed as an Ancient Monument. Albeit, at that time although some of old Dover was still standing following the War, this was succumbing to demolition in the twin names of reconstruction and progress.

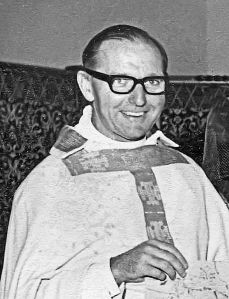

In 1963, the Chapel was designated for demolition along with adjacent buildings. Father Terence Tanner (1916-1982), Parish Priest of St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church responded by launching an appeal to buy all the properties. Patron of the appeal was former Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan (1894-1986) but two years later, the appeal was still £1000 short of the £12,000 needed. Dover Corporation gave £100 and Kent County Council another £100 and finally an anonymous donor gave £2,000 and the Chapel was saved!

On 16 November 1966, restoration began under the auspices of historic buildings architect and consultant, Anthony Swaine of Canterbury. The work was carried out between 1966 and 1968 by local craftsmen and local contractor, Richard Barwick’s, using only genuine medieval materials. The flagstones came from Faversham Abbey in Kent (1152-1160). The main part of the altar was built from recovered stone from Bell Harry tower of Canterbury Cathedral, (1475-1507). The ‘Mensa’ Stone (the top stone) of the altar is pre-reformation, and was found in a farmyard adjoining the church of St. Clement in Old Romney, Kent.

The two central tie-beams came from a barn on the Barham Downs at Elden, Kent. The east beam is original but it would appear that there was never a west beam. The roof is considered a fine and remarkable example of 13th Century construction. There is still a number of its original tenon joint securing pegs in place. The floor area in front of the altar was probably laid in the 14th century and has since remained undisturbed. The Crucifix on the east wall, is a contemporary carving in the style of the 13th century by Bob Forsyth. A small relic of St. Edmund in the south wall niche was donated by the Abbey of Pontigny, France, where St. Edmund’s shrine still stands today. The finished Chapel was presented, as it would have looked in the thirteenth century and therefore, there are neither pews nor fabric hangings.

On the right is the Cist under the Altar where the heart of St Richard was buried. Droitwich Heritage Centre

During the restoration, the Kent Archaeological Research Unit (KARU) under Brian Philp, conducted a 4-day archaeological investigation. The archaeologists removed nearly a metre depth of ‘soil’ to get back to the ground level of the 13th century. They dated the walls between 1150 and 1253 and the foundations of boundary wall after 1253. While they were excavating the archaeologists came across a nearly vertical tubular impression in the soil. The impression was left by a wooden stake and since rotted away, that had been driven into the ground to the Cist where the leather bag that contained the Saint’s heart lay. The stake enabled pilgrims to ‘touch’ the relic of St Richard and, it was reported, miracles were performed. The Cist is now empty but can still be seen.

The Chapel dedicated to St Edmund was re-consecrated on 27 May 1968 by Archbishop Cyril Cowderoy (1905-1976) of Southwark. In attendance was the Mayor of Abingdon, Leslie Steggles – an old boy of Dover Boys’ Grammar School. Following the consecration part of the bone of St Edmund enshrined in a gold reliquary was given to the Chapel by Henri Marie Charles Gufflet (1913-2004) the Bishop of Limoges, France. This was stolen in July 1973 but within days two local boys were arrested and the casket was returned.

Later that year, on 5 November, the St Edmund of Abingdon Memorial Trust was set up to maintain the building. A narrow passageway from Biggin Street to Priory Road that runs past the Chapel was named St Edmund’s Walk.

The Civic Trust was founded in 1957 and established their award scheme two years later. The Awards recognised the very best in architecture, design, planning, landscape and public art and in 1969 the Restoration of St Edmund’s Chapel won an award. Unfortunately, the judges had been told that Dover Corporation’s borough engineer, David Bevan, had initiated the restoration and he was given the prize. To give Mr Bevan his due, he did inform the Civic Trust that it was Father Terence Tanner who was responsible. Sadly, the Civic Trust went into administration in 2009 due to a shortage of funding.

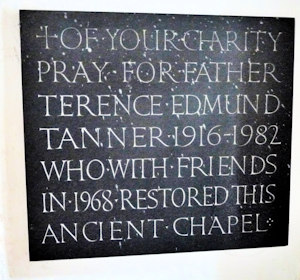

In April 1971 Father Terence Tanner of St Paul’s Church, Maison Dieu Road, was transferred to the smallest parish in the diocese at Goudhurst. No reason was given and it was met with considerable opposition. In June he left Dover following a failed appeal to Rome and was formerly seconded to work in drug rehabilitation in London. Father Tanner, the saviour of St Edmund’s Chapel died in Leominster in 1982. In recognition of Father Tanner’s endeavours, a memorial plaque is mounted in the Chapel and his ashes are interred close to the altar.

St. Edmund’s Ecumenical Chapel – accepts all faiths and denominations.

It is the smallest church in England that is still used for services.

For further information about St Edmund’s Chapel see: http://www.stedmundschapel.co.uk . Included on the website is a copy of Fr Tanner’s book which he produced following the restoration.

For the information on St Richard, thanks are given to Droitwich Spa Heritage Centre

Very interesting. Thank you for taking the time and trouble to do the research.

Useful much appreciated by Dover Greeters, who love to share our little chapel with visitors.

Thank you. I’ve been fascinated by the story of this chapel since moving to Dover 17 months ago. I also love the funny little passage that leads to it from Biggin St.