August 1914– Outbreak of World War I

On the perceived premise that Russia was about to attack Germany, the Germans, under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888-1918), in accordance with the Schlieffen plan, on Saturday 1 August 1914, declared War on Russia, invaded Luxembourg and crossed the French frontier at several places. In Britain, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, issued the order to mobilise all Royal Navy personnel and warships to establish a war footing. At Dover, Channel ferries were crossing Dover Strait at speed and out of schedule in an attempt to bring back as many people as possible from the Continent before War broke out. In towns throughout Britain crowds surrounded information posts to find out the latest news and in Dover one of the most popular was Leney’s brewery office on Castle Street. Leney’s was kept up to date by telephoning official bodies such as the Dover Coastguard at Spioen Kop wireless telegraph station on Western Heights.

The following day, Sunday 2 August, Germany demanded the right of passage for her armies through Belgium. Towards the end of July the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) No 1 Squadron had been designated an observation balloon squadron, made up of airships to be transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The aeroplane squadrons had been designated as RFC Nos. 2,3,4 and 5, primarily to be used for reconnaissance and were sent to St Margaret’s Aerodrome (Swingate) near Dover, and arrived that evening. During that day, Germany announced that she had joined in the mounting conflict on the side of Serbia and on 5 August Austria-Hungary also declared war on Russia. King Albert I (1875-1934) of Belgium (1909-1934) refused to comply with Germany’s request for safe passage for her troops through Belgium in order to attack France so Germany proceeded to march through Belgium. This violated the Treaty of London of 1839 that recognised and guaranteed the independence and neutrality of Belgium as well as confirming the independence of the German-speaking part of Luxembourg.

During Monday 3 August thousands of people came to Dover, some from as a far away as London to see the preparations that were being made for War. That day Germany declared War on France and thus laid the basis of the Western Front. At 13.00 the French cruiser squadron of six ships came up the Channel and the crowds lining the cliffs, cheered. At the time RFC No 2 Squadron, based in Montrose, Scotland had left for St Margaret’s Aerodrome (Swingate). One of their team, Lieutenant Hubert Dunsterville Harvey-Kelly (1891-1917) had, at the time, already arrived in Dover so he undertook a reconnaissance flight to ascertain the logistics of getting to France. He took off from St Margaret’s Aerodrome (Swingate) for the newly chosen site of Amiens Airfield, Saint-Fuscien, France at 06.25hrs that morning and returned to Dover by the time the rest of his squadron arrived in Dover.

The 1839 Treaty of London signatories: Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, German Federation, Russia and the Netherlands.

At 23.00hrs on Tuesday 4 August 1914, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith, on behalf of Britain, declared War on Germany in accordance with the 1839 Treaty of London. It was expected that Germany would realise she had not been in danger of being attacked by either Russia or France and on this realisation, the need for a War would cease with the possibility of hostilities on the Western Front would be over by Christmas. As we know, this did not happen for hostilities had already broken out by Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia prompting Russia to start mobilisation for war. Austria-Hungary’s ally Germany had demanded Russia to cease preparations but they refused, hence on August 1st, they declared war on Russia creating the Eastern Front. On 23 August Japan declared war on Germany after the latter refused to withdraw its warships from protecting its Chinese colony of Tsingtao, creating a Far Eastern Front. During this time political fractions in Italy decided to go to war against Austria-Hungary creating an Italian Front. Some three months later the Ottoman Empire, that had controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia and North Africa since 1299, joined in on the side of Germany and Austria-Hungary creating the Balkan Front. The result was an intensive and vicious World War that was to last until 11 November 1918.

Commander of the BEF Sir John French and Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith at BEF Headquarters, 1915. The War Illustrated

In Britain, meetings of ministers, chiefs of staff and other senior officers took place on 5th and 6th August in what was described as a Council of War. Using the major element of the Haldane report, the decision to send a British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France to stop any German advance on Paris was ratified. This consisted of six infantry divisions and five cavalry brigades under the command of Sir John French. The BEF’s 1 Corps was under the command of Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) and II Corps under the command of Sir James Greirson (1859-1914). Until November it appears that the Cabinet made decisions over the general conduct of the War.

On Monday 10 August some fourteen hangers were erected at St Margarets / Swingate aerodrome, Dover, by which time there was a large assembly of aeroplanes and more were arriving from all over Britain. The same day, France declared war on Austria-Hungary and two days later Britain also declared war on Austria-Hungary. Both aeroplanes and seaplanes escorted the BEF across the Channel to France and occasional bombing was achieved by the pilots dropping 10lb and 20lb bombs over the side of the plane. A seaplane base was established at Ostend, Belgium, attached to Dover, with the order to escort the BEF 1 Corps under the command of Sir Douglas Haig. Sir John French landed in France on 8 August.

A small RFC advance party of ground crew and personnel of 3 Squadron led by Major (William) Geoffrey Salmond (1878-1933) on 11 August, left from Newhaven for Boulogne and then on to Amiens. On arrival in Boulogne they were greeted with flowers and shouts of ‘Vive l’Angleterre’. Their job was to prepare Amiens airfield at Saint-Fuscien, a commune in the Somme department, for the arrival of the main contingency of the RFC and their aeroplanes. That same day Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson was appointed to command the RFC in the field. He left Farnborough, crossing the Channel from Southampton arriving Amiens on Thursday 13 August. That day the new airfield was named Amiens Aircraft Park. During World War I two Amiens Aircraft Parks opened on the designated Amiens airfield, 2 and 102 which was north of the actual village of Saint-Fuscien and north-east of the modern junction of the A29/E44 and the D7. After the war the former Aircraft Park became a private airfield under the name Amiens-Montjoie and subsequently was returned to agriculture.

The Swingate memorial to the Royal Flying Corps 2,3,4,5 Squadrons that flew to Amiens in 1914 as part of the BEF. Alan Sencicle

On the afternoon of 12 August and the morning of 13 August 2, 3, 4 and 5 Squadrons in 56 aeroplanes left Swingate for Amiens Aircraft Park, at intervals of about one minute. As soon as the individual Squadron’s aeroplanes left Dover their ground crew left for Boulogne by sea then overland to the Aircraft Park with stores, tools, equipment, spares, supplies, horses and vehicles. On arrival in France, a total of 63 aeroplanes, 105 officers, 755 men and 320 transport vehicles made up the RFC (BEF) air support contingent. From then on the name Aircraft Park was given to the travelling base of Squadrons for the remainder of the War and not only carried the basic provisions like those brought from Dover but reserves of equipment and aircraft. Some of these were transported in crates or flown over to France by personnel of the Aircraft Park or by spare squadron pilots.

The BEF II Corps under the command of Sir James Grierson embarked for France on 15 August escorted across the Channel by seaplanes. On arrival in France the contingent left by train for Amiens but just before arrival at 07.00hrs on 17 August Grierson died of a heart attack. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930) who arrived on 20 August replaced him.

Not all the aeroplanes that left Dover for France went to Amiens. Many flew on to Maubeuge, close to the Belgian border, northern France, and close to the Front Line. Nearby was a French military aerodrome and from 16-23 August this became the HQ of the RFC. From 24 August the confrontation against the German invasion forces were coming closer so the RFC looked for another base. On 27 August the Marines of the Royal Naval Division landed at Ostend in Belgium to safeguard the town. Their duties included protecting the British seaplane base there before re-embarking on 31 August for Dunkirk. At 13.00 hours on 29 August the German main assault began and the French were gradually overrun. Maubeuge was captured on 7 September and remained in German hands until 9 November 1918. On 21 August at the Battle of Charleroi the weight of the German offensive drove the French and Belgians back. From both cavalry and air reconnaissance reports, it was evident that the German forces were rapidly closing in on the Belgium town of Mons and on 22 August the BEF moved up to Mons with the intention of supporting the French Fifth Army. The tactic was in two lines, like a broad arrow with its tip at Mons. German superiority, which included the use of aeroplanes in combat, overcame the Allies resistance. The Battles of Le Cateau (25 August), Noyon (26 August) and St. Quentin (29–30 August) followed.

Wing Commander Sampson and the first RNAS unit, the Eastchurch Squadron, landed in France on 27 August. On Tuesday 1 September they were renamed No.3 Squadron RNAS and had arrived at St.Pol-du-Mer aerodrome, Dunkirk, Flanders, close to the port of Dunkirk. The airfield had opened in 1913 but at the outbreak of War the French authorities commandeered it for their air force who were assigned to attack and bomb German military installations in Belgium. As the Protection of Dunkirk was paramount the RNAS were given use of the aerodrome as an emergency-landing depot. In return, but against orders from the British Army command, RNAS pilots attacked and bombed German military installations in Belgium! Following the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force in Flanders, No.3 Squadron RNAS were assigned to escort them to the battle area and subsequently took an active part in their defence. Throughout this time Ostend remained under constant attack and on 15 October the Germans captured both the town and port.

Having been effectively mothballed at Christmas 1913, the Hermes was decommissioned by Commander Charles Laverock Lambe (1875-1953) on 31 August 1914 as a seaplane tender. On 30 October, captained by Lambe, she arrived at Dunkirk having brought seaplanes from Portsmouth. On the following day, off Calais, a German U-27 submarine sank the Hermes but the South Eastern and Chatham Railway Company’s Cross Channel packet Invicta and two destroyers rescued Commander Lambe and the crew. Squadrons from Swingate and Dunkirk, on 23 November, successfully bombarded the Belgium port of Zeebrugge, then later on 21 January 1915, German submarines moved into newly built bases the main one of which, for the Channel, was at Bruges with outlets at Zeebrugge and Ostend. Squadrons based at Guston airfield, near Dover, used the airfield at Dunkirk, and on 23 January 1915, they attacked German submarines at Zeebrugge. On 12 February, under the direction of Sampson, 34 aeroplanes attacked various submarine bases in Belgium and on 16 February, 48 aeroplanes bombarded Ostend, Middelkerke, Ghuistelles and Zeebrugge, Belgium.

Flight Lieutenant Harold Rosher (1893-1916), of No 1 Squadron based at Guston and using the Dunkirk airfield, wrote to his parents telling them of the raid, saying, ‘… my order were to drop all my bombs on Zeebrugge … we went in order … slowest machine first, at two minute intervals … we had four destroyers at intervals across the Channel in case we our engines went wrong, also seaplanes. It was mighty comforting to see them below.’

Shortly after the Admiralty decided to make Dunkirk an aeroplane base and from there large scale air raids on the Western Front, went from Dunkirk airbase and other bases in France. The RNAS remained at Dunkirk throughout the War even when the American Naval Air Service arrived in 1917. From November 1918 to April 1919 the 8th Canadian Stationary Hospital took over Dunkirk’s hospital. During the War it is estimated that 7,500 shells and bombs fell on the town, yet shipbuilding and other port activities continued. Located at the south-eastern corner of Dunkirk is the Town Cemetery where there are 460 Commonwealth graves of World War I service men of which ten are unidentified. The graves can be found in Plots 1 to 3 of the public part of the cemetery to the right of the main entrance and in Plots 4 and 5 of the Commonwealth War Graves section adjacent to the Dunkirk Memorial.

On 12 August 1914 the order was issued for the Army to construct a temporary camp north of the village of Catterick, North Yorkshire to accommodate two complete divisions with around 40,000 men in 2,000 huts. The base was originally named Richmond Camp but was changed to Catterick Camp in 1915. In less than a month, south of the village, the RFC Catterick aerodrome opened to train pilots and to assist in the defence of northern England. On formation of the Royal Air Force (RAF) on 01 April 1918 Catterick aerodrome was renamed RAF Catterick and became 49 Training Depot Station. In 1927 to July 1939, coming under Army Co-operation Command, RAF Catterick supplied any requirements the army had for air support. In 1935, the site had been subject to a major expansion programme when most of the original buildings were demolished and replaced on a much grander scale.

At the outbreak of World War II RAF Catterick became a Fighter Sector Station within 13 Group Fighter Command and in 1943 the Station Block was replaced by a protected operations block identical to those built at other WWII Fighter Sector Airfields. The last fighter to use the airfield was in March 1944 from when RAF Catterick was downgraded to a second line airfield becoming, in 1945, an air crew allocation centre. That year the war film ‘The Way To The Stars’ was shot at Catterick and the opening scene is of the airfield – deserted.

In 1946 the RAF Regiment depot and the Band of the RAF Regiment moved to RAF Catterick from Belton Park, Grantham, and for nearly 50 years the station became a training establishment where all ranks in the RAF gained their professional skills. The introduction of the regular use of aircraft powered by jet turbine engines spelt the end of Catterick airfield as the single runway could not be extended due to the AI at one end and the River Swale at the other. In consequence the airfield was only used for light communications aircraft and gliders and the flying units were redeployed to other stations.

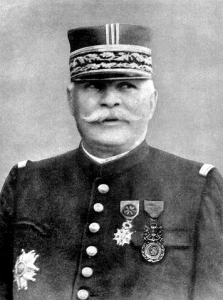

French Commander-in-Chief, General Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre (1852-1931) Nations at War by Willis John Abbot (New York, 1917)

On 1 July 1994 RAF Catterick closed and the base was transferred to the British Army as Marne Barracks part of the Catterick Garrison, the largest British Army garrison in the world. Of note, Marne Barracks is named after the site of two significant WWI battles. The First Battle of the Marne between 6-12 September 1914 and the Second Battle, which took place 15-18 July 1918. The first Battle centered on a joint offensive by the French and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) against the advancing German Army who were within 30 miles of Paris. The RFC played a vital reconnaissance role that maintained accurate information to the ground forces. After which the French Commander-in-Chief, General Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre (1852-1931) thanked the RFC aviators for being kept accurately and constantly informed of General Alexander Heinrich Rudolph von Kluck’s (1846-1934) movements adding that ‘To them he owed the certainty which had enabled him to make his plans in good time.’

Once work started on RFC Catterick, the RFC were looking for another airfield in the north of England to work alongside Catterick aerodrome. Back in 1910 it was reported that aviators found the long sandy beach of Marske-by-the-Sea, about 5 miles west of Redcar, North Yorkshire, was an excellent landing ground. They noted that although Marske-by-the-Sea airfield had opened on 25 June 1910, due to the lack of facilities it had been rejected by the RFC at the time. Nonetheless, the RFC officers of 1914 decided to have another look and noted that, indeed, it did lack the relevant infrastructure. However, they were told that about 14 miles west of Marske-by-the-Sea airfield, on the south bank of the River Tees, there was once an air display at Thornaby-on-Tees. Further, the display featured the famous aviator, Gustav Wilhelm Hamel (1888-1914). Earlier in 1914 Hamel had made the headlines when he had attempted to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in a specially built Martin-Handasyde monoplane. Not long after, on 22 May 1914, he had made the headlines again when he disappeared while flying a Morane-Saulnier monoplane across the English Channel. His body was found off Boulogne on 6 July but there was no trace of his aircraft and due to the international tensions of the time the media reports implied that Hamel’s death was suspicious.

On checking army records the officers could not find any mention of an air display at Thornaby-on-Tees or even a possibility of an airfield. Further, Hamel was dead so was unable to confirm either way. Nonetheless, they paid a visit to farmer Matthew Young of Vale Farm, who owned the land where the supposed display had taken place. The farmer confirmed that on a summer’s day in 1912 he had been paid 100 gold sovereigns to let one of his fields for use of an air display. Those behind the display had advertised the event and on the day spectators, aeroplanes and aeronauts turned up. He showed RFC officers a cutting from a local paper. This confirmed what farmer Young had said and a paragraph mentioned the death of aviator Edward Petre in 1912. He had been killed while trying to land on Marske beach having crashed near the village Church.

The RFC officers then inspected the Vale Farm site at Thornaby-on-Tees and were pleased to note that it was close to the Tees Valley Railway Line, which ran between Bishop Auckland and Redcar via Darlington. The site had other aspects in its favour and immediately they commandeered it. Soon after the Thornaby-on-Tees airfield was laid. At the same time Marske-on-sea airfield was commandeered and a railway line spur was laid between Redcar and Saltburn-by-the-Sea, about 2miles away from Marske. Thornaby-on-Tees airfield was detailed to bring in goods and equipment and work started on creating Marske military aerodrome by laying a larger runway and buildings of the standard RFC design. When completed, Thornaby airfield became a staging post between Catterick Aerodrome and Marske air gunnery school. It was not until the mid 1920s that RAF Thornaby was commissioned as an airfield and in 1939 it came under the control of RAF Coastal Command. During World War II it was mainly used for reconnaissance work, anti shipping strikes, and attacks on enemy airfields etc. The base closed to flying in October 1958 and was sold to Thornaby-on-Tees Borough Council for redevelopment in 1963.

From 1 November 1917 Marske military aerodrome specialised in training qualified pilots in tactics and methods of aerial combat and between April and August 1918 William Earl Johns (1893-1968), author of the fictional air-adventurer Biggles was a flying instructor there. During the Battle of the Somme, on 21 April 1918, the famous German flying ace Manfred von Richthofen (1892-1918) ‘The Red Baron’ was leading 20 Albatross Scouts, D5s and Fokker triplanes towards the British lines. The formation was seen by Captain Arthur Roy Brown (1893-1944), a 24-year-old Canadian pilot leading eight RAF Sopwith Camel biplanes of 209 Squadron who went into attack. Manfred von Richthofen was killed and Brown was officially partially credited by the RAF, with his death along with Australian anti-aircraft gunner Sergeant Cedric Popkins (1889-1968). Brown’s citation states: Lieutenant (Honorary Captain) Arthur Roy Brown, DSC.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On 21 April 1918, while leading a patrol of six scouts, he attacked a formation of 20 hostile scouts. He personally engaged two Fokker triplanes, which he drove off; then, seeing that one of our machines was being attacked and apparently hard-pressed, he dived on the hostile scout, firing all the while. This scout, a Fokker triplane, nose dived and crashed to the ground. Since the award of the Distinguished Service Cross he has destroyed several other enemy aircraft and has shown great dash and enterprise in attacking enemy troops from low altitudes despite heavy anti-aircraft fire. London Gazette (Supplement). 18 June 1918. p. 7304

Nine days after the combat with von Richthofen, Brown was admitted to hospital with influenza and nervous exhaustion and in June, he was posted to No. 2 School of Air Fighting at Marske Aerodrome. There he joined William Earl Johns (1893-1968) the author of the fictional air-adventurer Biggles, as an instructor. On 15 July Brown was involved in a nasty air crash and spent five months in hospital. He left the RAF in 1919 and returned to Canada. Marske School of Air Fighting closed in November 1919. During World War II the site was taken over by the Royal Artillery but the airfield remained in case of emergencies. In the 1990s all that was left was demolished and part of the site was sold for housing. Albeit in St Mark’s Church in Marske the aviator’s window has images and a dedication to the young men who trained at Marske Aerodrome!

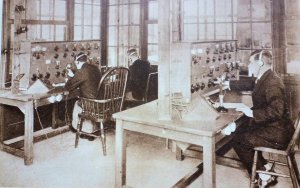

Sir Winston Churchill, as the First Lord of the Admiralty, took over full responsibility for Britain’s aerial defence in September 1914 and made several visits to France to oversee the war effort. Back in March 1913 an experimental branch of the Military Wing of the RFC was formed to research into ballooning, kiting, photography, meteorology, bomb-dropping and wireless telegraphy. The latter led to the creation of the Headquarters Wireless Telegraphy Unit (HQ WTU) on 27 September 1914. Between 13 –28 September during the Battle of the Aisne the Germans were pushed northwards and the RFC pilots took aerial photographs. No 4 Squadron special Wireless Flight under Hugh Dowding, later IX Squadron RFC, used wireless telegraphy to aid reconnaissance in guiding the artillery and in particular ranging onto targets. Shortly after the RFC chose another site for an airfield at Writtle near Chelmsford, Essex. A traditional picture postcard English village set in rolling countryside with pretty churches, timbered houses and a village green complete with duck-pond. It was believed to be on the flight path between Germany and London for Zeppelin attacks.

WWI Observer testing wireless transmitter of his Armstrong-Whitworth F.K.8. at Poperinghe 17.02.1918 Nederlands Nat Arch

Two fields were cleared for the 22 acre site and with temporary facilities established the airfield opened in October 1914. However, as the village was not subjected to any aerial attacks Writtle airfield was soon after downgraded. Allocated to No 1 Reserve Aeroplane Squadron as a temporary landing ground, occasionally fighter patrols landed and a closing order was issued for November 1916. Long before that date the Marconi Company showed an interest to use the airfield for pioneering flying radio tests and the site was rented to them. Prior to the War, every evening a wireless time signal was transmitted from the Eiffel Tower in Paris and that was the only regular broadcasting service in the world! Further, only those with Marconi sets could receive the signal. As the War progressed, official wireless telegraphy became more sophisticated and increased in frequency, but messages were in cipher and sent by Morse code! To help reconnaissance, by early 1915, two-seater aircraft were equipped with a radio transmitter but no receiver so artillery batteries were required to communicate with aircraft by laying strips of white cloth on the ground in prearranged patterns. The Writtle airfield with the Marconi company, using Airco DH6 and then Avro 548 aeroplanes to test their developments in radio communication, became important to the progress of the War. The Marconi Company left Writtle in 1924.

As noted above, on 29 August 1914 the Germans launched their main assault on the Western Front and the French were eventually overrun. Maubeuge, the town where the RFC HQ was first located, was captured on 7 September by which time it had been moved to Clairmarais, Longuenesse, in the Pas-de-Calais, about a mile from the centre of St Omer. Near a small chateau at the foot of a hill was a racecourse, which made an excellent airfield and on 11 September 1914 the first RFC aeroplane landed at what was first named Clairmarais Aerodrome but by then had been renamed St Omer Aircraft Park. On 8 October 1914 the castle overlooking the airfield became the new Headquarters of the RFC on the Western France. It was not long after that St Omer Aerodrome was renamed again and housed not only the HQ operational squadrons but all squadrons being deployed in France before going on to other locations.There was also a Pilots Pool, as well as support, repair and wireless units and training facilities for RFC service officers and men first arriving in France.

As the War progressed all new Squadrons that were formed on the Continent, formed at St Omer Aerodrome and this necessitated increasing the number of aircraft and pilots there. As equipment had to be repaired and machines put back together again after encounters, St Omer Aerodrome rapidly became the forefront of a huge and growing behind-the-scenes operation base. Hence, as the physical establishment grew the airfield itself was extended such that by the time the Americans arrived in 1917, St Omer airfield was the largest British airfield on Western Front. By then logistical support was its primary function. Between the start of the War and Christmas 1914, while St Omer’s aerodrome was expanding so was the RFC and the Army. In October 1914, the Army’s 7th Division arrived by sea in France and formed the basis of III Corps. The cavalry also grew after their arrival on the Continent and formed the Cavalry Corps made up of three divisions. By December 1914, the BEF had also expanded to such an extent that the First Army and the Second Army were formed.

King Albert I of the Belgians and General Hubert Gough on the old Somme battlefield. Netherlands National Archives

In October 1914 Churchill visited Antwerp to observe Belgian defences against the besieging Germans and promised Belgian Minister of War (1912-1917) Charles de Broqueville (1860-1940) that Britain would provide reinforcements for the city. The Belgian constitution prescribed that King Albert I was in command of the Belgium army and he agreed with Churchill to hold the Germans off long enough for Britain and France to regroup. However, Broqueville wanted Belgium to be an unprovocative neutral power, in consequence Churchill left the city and agreed to the BEF retreat. This allowed the Germans to take Antwerp for which Churchill was heavily criticised but countered by arguing that his actions prolonged the resistance that enabled the Allies to secure Calais and Dunkirk. In October the de Broqueville government moved to Le Havre in France, while King Albert I established his staff in the Flemish town of Veurne, Belgium, making it clear that it was inappropriate for the King to leave his own country.

Back in Britain, the RFC continued to look for more potential airfield sites and Hounslow Heath, west of London, was known to a number of them. From Roman times the Heath was recognised for its strategic importance when main roads cross it between London and the west and south west of England. Due to its flatness and its relative proximity to the Royal Greenwich Observatory, in 1784 the Heath was chosen as the base line by the Ordnance Survey when mapping the whole of the United Kingdom. From 1793 to early twentieth century the Heath was used as a training ground for horse-mounted cavalry based at Hounslow Barracks and in 1909, like many other open areas, following Bleriots successful Channel crossing, the Heath became a fascination for would be aeronautics. Within a year a hangar was built to support a proposed flying training for army officers following which the Heath became a popular but unlaid airfield. In the summer 1914, approval was given for the site to become RFC Hounslow and Hounslow Heath Airfield opened on 14 October 1914 when a grass airfield was laid. Two B.E.2c aircraft landed on the Heath airfield from Brooklands aerodrome that day and by spring the following year some 200 military personnel had received intensive air training there. Following which the Hounslow Heath Aerodrome was used for both training and in April 1916 a base for No 39 Squadron Home Defence fighters, as part of a ring of ten aerodromes around London to protect the City from Zeppelins.

The training at RFC Hounslow was aimed at the development of pilots, aircraft and squadrons ready for transfer to battlefronts in France, the first of which was 10 Squadron RFC. They arrived from Farnborough Airfield at the end of March 1915. They were followed by 14 Squadron in May for training and in August 14 Squadron they left for France. Both squadrons were equipped with B.E.2cs. In September 24 Squadron was formed at Hounslow Heath Aerodrome, which was initially commanded by Captain Lanoe George Hawker (1890-1916) before he too left for France. There Hawker was credited with seven victories and became the third pilot to receive the Victoria Cross but he too was killed in a dogfight against the Red Baron, von Richthofen. 24 Squadron finished training in February 1916 when they were posted to France. Throughout the War several more front line squadrons formed and were trained at Hounslow Heath Aerodrome. On formation of the Royal Air Force on 01 April 1918 Hounslow Heath Aerodrome was renamed RAF Hounslow and became a Training Depot Station. Following the November 1918 Armistice, the airfield continued to operate on the Heath and was the only London aerodrome with customs facilities. Then in May 1919 it was announced that the airfield would be reserved entirely for civil aviation and the following August a number of early airlines, headed by Aircraft Transport & Travel began the world’s first international air services. However, at about the same time it was also announced that Croydon Airport would became London’s Airport replacing Hounslow Heath Aerodrome on 28 March 1920.

In 1919 the Australian government offered a prize of £A10,000 for the first Australian in a British aircraft to fly from Great Britain to Australia. Ross Macpherson Smith (1892-1922) his brother Keith Macpherson Smith (1890-1955) together with James Mallett (Jim) Bennett (1894-1922) and Walter Henry Shiers (1889-1968), flew from Hounslow Heath Aerodrome, on 12 November 1919 in a Vickers Vimy (G-EAOU), eventually landing in Darwin, Australia on 10 December, taking less than 28 days. The four men shared the £10,000 prize money and initially appeared to cement Hounslow Heath Aerodrome standing as London’s main permanent international airport. However, as noted planners favoured Croydon Airport as London’s approved airport and on 28 March 1920 the last commercial flights took place from Hounslow Heath Aerodrome. The Army repossessed Hounslow Heath Aerodrome for use as a repair depot and training school and in the 1930s, occasionally aircraft demonstrations took place. By the end of World War II what had been Hounslow Heath Aerodrome had largely reverted back to an undeveloped public open space. At the time of writing the area is managed for wildlife and supporting several rare or declining plant and animal species.

Northolt airport in South Ruislip, West London, boasts of having the longest history of continuous use of any RAF airfield. These days it is used by both military and civilian aircraft and is the home to units from all three Armed Services and the Ministry of Defence. The early fitful history of Northolt airport dates back to 1910, when aviator, Claude Grahame-White (1879-1959) purchased more than 200 acres of land converting Hendon balloon airfield into a recognised airfield for aeroplanes. Within a year, Hendon aerodrome became the main London airfield and the first ever ‘official’ UK airmail was flown from Hendon to Windsor and vice versa. The following year, 1912, a group of businessmen decided to develop another airfield in west London that they named ‘Harrow Aerodrome’. The project was floated on the Stock Exchange but came to nothing. In 1914 one of the RFC officers looking for suitable airfield sites, Major William Sefton Brancker (1877-1930), undertook aerial surveys of Glebe Farm in Ickenham, Hundred Acres Farm and Down Barnes Farm in Ruislip. The latter was close to Northolt Railway Junction, a Great Western Railway and Great Central Railway joint line to High Wycombe carrying services from both Paddington and Marylebone railway stations.

Before the year was out Brancker put forward his recommendation and in January 1915 the government requisitioned the land. Northolt airfield opened on 1st March 1915 and on 3 May the No. 4 Reserve Aeroplane Squadron was relocated from Farnborough and the airfield was officially named ‘RFC Military School, Ruislip’ but was generally called Northolt. The airfield was designated as part of the ring of ten aerodromes around London to protect the City from Zeppelins and No. 4 Reserve Aeroplane Squadron was heavily involved flying Bleriot Experimental biplanes.

In 1916 No 43 Squadron was formed at Northolt under the command of Major William Sholto Douglas (1893-1969), flying Sopwith 1½ Strutters built by the Fairey Aviation Company, North Hyde Road, Hayes, Middlesex, for Sopwith Aviation Company owned by Tommy Sopwith (1888-1989). The Strutter made its first test flight from Northolt in 1916 flown by Harry Hawker (1889-1921) Sopwith’s chief test pilot. Fairey Aviation Company had been founded by electrical engineer Charles Richard Fairey (1887-1956) known as Richard Fairey and Belgian engineer Ernest Oscar Tips (1893-1978) both having previously worked for Sopwith Aviation. Richard Fairey attended Merchant Taylors school in Northolt and possibly because of his affinity to the town from 1917 Fairey’s Company continued to conduct test flights there after World War I.

When the Royal Air Force was formed on 01 April 1918 the aerodrome became RAF Northolt but following World War I the Sopwith Aviation Company had gone bankrupt. Tommy Sopwith along with his test pilot Harry Hawker and three others bought the assets and formed H.G. Hawker Engineering in 1920. The Company was renamed Hawker Aircraft Ltd in 1933 when it built the Hawker Interceptor Monoplane. This went into production and entered squadron service in December 1937, with Northolt being the first station to take delivery. In World War II Northolt played a key role in defending the UK during the Battle of Britain and was the home to Polish fighter Squadrons. Following the War, both military and civilian aircraft used RAF Northolt then in May 1954 the station reverted back to military use. In 1995 the Royal Squadron was reformed and amalgamated with the Queen’s Flight as 32 Squadron based at Northolt. This operates in VIP and general air transport roles augmenting the duties of RAF Uxbridge.

Based at RAF Uxbridge is former Queen’s now the King’s Colour Squadron, which undertakes ceremonial duties. From 1990 it also became operational as field squadron RAF 63 Squadron. When on 31 August 1997 Diana, Princess of Wales was killed in a car crash in Paris her body was taken to Villacoublay airfield, Paris. From there she was flown to Northolt and met by eight members of the Queen’s Colour Squadron, who acted as the coffin-bearer party.

Queen Elizabeth II died on 8 September 2022 at Balmoral Castle, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Her body was taken to Edinburgh Airport on 13 September and flown to Northolt. The Queen’s Colour Squadron transferred the coffin from the aircraft to the hearse, which was taken by road to Buckingham Palace. Following the accession of King Charles III, the Queen’s Colour Squadron’s name was changed to King’s Colour Squadron on 27 October 2022.

At Northolt in April 2013 it was proposed to increase the number of private flights from 7,000 to 12,000 per year as part of plans to increase the income generated by the station. At the time of writing, Northolt has one runway in operation, spanning 5,535 feet × 151 feet (1,687 metres × 46 metres), with a grooved asphalt surface.

Although Great West, Croydon and Heathrow were airfields of the future they fit here as the seeds were sown early in World War I. As noted in the section above, Richard Fairey’s Aviation Company designed and manufactured aircraft at their factory in North Hyde Road, Hayes, Middlesex, and undertook their flight testing at Northolt Aerodrome up until 1928. That year the Air Ministry gave notice to the Company for them to vacate the aerodrome, which meant looking for another airfield or site near to their factory. The Company’s chief test pilot, Norman Macmillan (1892-1976) was in the RAF and in 1925 had made a forced landing and take off from flat farmland near the hamlet of Heath Row, in the parish of Harmondsworth, Middlesex. This was about three miles by road from the Hayes factory so he took surveys of the area and recommended the site. At the time it was still being used for farming and for market gardens. Fairey Aviation Company Ltd offered £10 an acre, the then market rate, and bought 177 acres (72 hectares) of the land. They laid a grass airfield, built a hangar and Harmondsworth Aerodrome became operational in June 1930 for testing aircraft.

Over the next ten years Fairey bought a further 53 acres (21 hectares) of adjacent farmland and in May 1935, put on the airfield’s first airshow, advertised to take place at Heathrow Aerodrome, Harmondsworth. Four years later, using the same airfield, their airshow was advertised as taking place at the Great West Aerodrome, near Hayes. During World War II the aerodrome was used as an emergency back up airfield to RAF Northolt and in the meantime Fairey bought 10 more acres of farmland to incorporate into his Great West Aerodrome. In 1942 Fairey was knighted and planned to move the factory nearer the aerodrome once the War was over. This seemed credible in 1943 when the government started to look at possible post war reconstruction and as London’s pre-war major airport was Croydon, it was generally expected that it would take up that role and Croydon Aerodrome would be expanded accordingly.

During the following year the outcome of the War was looking increasingly positive

and Fairey was confident that he could expand Great West Aerodrome to meet the needs of his planned expanding business. At the same time post war redevelopment of London had become the government’s priority especially as the blitz had destroyed great swathes of the city. By the end of the War over 50,000 inner London homes were completely destroyed and more than 2 million dwellings suffered some form of bomb damage. In preparation, London County Council had commissioned architect and urban planner John Henry Forshaw (1895–1973) and architect and town planner Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie (1879–1957) to produce The County of London Plan. This had been published in 1943 and was immediately followed by Abercrombie’s tome A Greater London Plan.

The latter was an expansion of the County plan and focused on five main issues facing London: population growth, housing, employment and industry, recreation and transport. The Cabinet decided that the details of the plan were to be kept secret until final decisions were made as land would have to be requisitioned. Due to lack of money such requisitions were to be under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 as this World War I legislation provided no obligation to pay compensation to the landowners. Abercrombie’s plan was published on 14 December 1944 with the final section of the report, transport, focusing on roads and railways with lip service being paid to air transport stating there would be a ring of airports round London. This was based on the ten, designated in World War I, airfields suggesting that there would be one large trans-ocean airport that would be Heathrow, twelve miles from Victoria railway station!

Captain Harold Harington Balfour MP, Under Secretary of State for Air, sitting at his desk at the Air Ministry 1939-1945

This was the first time both Croydon airport management and Fairey the owner of the Great West Aerodrome had heard of the decision and they were furious. At the time, Sir Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair (1890-1970) was the Secretary of State for Air in the coalition Churchill government and a keen aviator. He had been given the remit to find an appropriate site and produce the plans for the proposed trans-ocean airport. Sinclair gave the project to his Under Secretary, Harold Harington Balfour (1897-1988), a WWI ace, and it was he that was instrumental in the choice of the Great West Aerodrome.

Although Fairey could not claim compensation for the loss of his Great West Aerodrome the government, praising their own generosity, offered him £10 an acre – the same amount as he had paid for the original parcel of land. Fairey refused, so the Air Ministry requisitioned the whole aerodrome land without any compensation. This, however, did not include many of the airport buildings so Fairey continued using the airfield to fulfill his wartime contracts. As a retaliation the Ministry of Aircraft Production delayed sanction on the contracts until the company moved to another airfield. Fairey’s Aviation Company moved twice but neither of the aerodromes could accommodate their needs. Thus Fairey continued to fight for adequate compensation but the Great West Aerodrome was officially renamed Heathrow Airport and designated for use by RAF Transport Command.

On 19 December 1945, the British Transport Policy White Paper was published in which all airport services were placed under national ownership and control. Also which airports were to be used for scheduled services. Three corporations were also set up, they were the British Overseas Airways Corporation (B.O.A.C) to run the Commonwealth, Atlantic and Far East routes; the second, at the time unnamed, for the internal services and those to and from the Continent of Europe and the third, also unnamed, for the South American route. The White Paper stipulated that until parliamentary approval was given, the Associated Airways Joint Committee was to continue to operate internal services and B.O.A.C together with RAF Transport Command would operate external routes.

Although the White Paper mentioned Heathrow Airport, saying that it was expected that two runways would be completed by February 1946 and it would be developed to the highest international standards. However, for a short period Hurn, now Bournemouth, airport served as London’s international airport until the opening of facilities at Heathrow by the Minister for Civil Aviation Rt. Hon Lord Reginald Fletcher (1885-1961) Lord Winster. Heathrow International Airport was formally opened on 01 January 1946 when the airport was handed over to the Ministry of Civil Aviation. During this time, legal proceedings for adequate compensation continued by Fairey, which meant, among other things, the former Fairey hangar was not allowed to be demolished. It stood in the way of the proposed developments and this impasse lasted until 1964 when the hangar was incorporated into Heathrow Airport as a fire station.

As noted above, with the constant threat of attacks from Zeppelins in World War I, ten aerodromes were commissioned to form a protecting ring around London. Another such one was Beddington Aerodrome, north-east Surrey, an RFC station that opened in December 1915 adjacent to Plough Lane. In the following month two B.E.2Cs arrived as part of Home Defence. The station, named RAF Beddington, subsequently became a Reserve Aircraft and Training aerodrome and later in 1918 became a training airfield in its own right. Prince Albert (1895-1952) – later George VI (1936-1952) – having served in the Royal Navy transferred to the newly formed Royal Air Force. In 1919 he gained his ‘wings’ at Beddington with 29 Training Squadron, the first member of the royal family to learn to fly. Within a year his elder brother, Edward, Prince of Wales (1894-1972), later Edward VIII (1936), also received flying training with 29 Training Squadron at Beddington.

About this time across Plough Lane, an aircraft testing facility for De Haviland DH9s, Waddon Aerodrome was laid. On 29 March 1920 the two aerodromes were combined to become Croydon Aerodrome. Advertised as the gateway for all international flights to and from London replacing Hounslow Heath’s function. However, Plough Lane remained a public road so a man with a red flag was employed to stop traffic when an aircraft were due until a gate replaced him! Eventually, Plough Lane was temporarily cut into two dead ends that were never reunited – the old road is now parkland.

Croydon aerodrome quickly proved successful in attracting British and foreign airlines operating domestic and international flights and on 25 August 1919 Croydon inaugurated the first London to Paris air service. Soon after the Croydon to Le Bourget near Paris became the world’s busiest air route! Albeit, fog was a constant problem and at such times Penshurst aerodrome, a military airfield in Kent, was designated as an alternative destination. In 1921 Croydon became the first airport to introduce Air Traffic Control. Further, as both the French and German governments were heavily subsidising their airlines, the British government decided that they too would help to establish a British airline based at Croydon aerodrome. Two years later the Secretary of State for Air, Samuel Hoare (1880-1959), provided a £1 million state subsidy over ten years to aid the merger of Britain’s four principal private air carriers. These were British Marine Air Navigation Company Ltd, the Daimler Airway, Handley Page Transport Ltd and the Instone Air Line Ltd. The amalgamation, named Imperial Airways Limited, was launched on 31 March 1924 based at Croydon aerodrome.

Croydon ‘Wireless Transmission room between pilots in the air on directions & weather conditions.’ Gvt publicity 1924

Less than a year later, on 24 December 1924, an Imperial Airways de Haviland DH.34 crashed at nearby Purley with the loss of eight lives. The subsequent Public Inquiry led to the 1925 Croydon Aerodrome Extension Act and major expansion and redevelopment of the aerodrome took place. This included a new airport terminal; airport control tower, the first airport hotel and extensive hangars. Lady Maud Hoare (1882-1962) opened the complex on 2 May 1928. Of note, many of the procedures, training and concepts developed at this complex are still used today. From March 1937 British Airways Ltd started operations from Croydon to serve European routes while Imperial Airways, served routes to the British Empire. On 3 September 1939 World War II broke out and Croydon International Airport became RAF Croydon. During the Battle of Britain (10 July-31 October 1940) it became a fighter airfield and in 1943 the RAF Transport Command was founded at Croydon when thousands of troops were transported in and out of mainland Europe. Meanwhile, on 24 November 1939, the British Overseas Airways Act was ratified creating British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) to become Britain’s state airline.

Following the War on 1 August 1946 British European Airways (BEA) division of BOAC became a crown corporation in its own right. Much later on 1 April 1974 BOAC was merged with BEA to form British Airways. In 1946, it was expected that Croydon would resume its pre-war eminence as London’s International Airport. However, in 1952 the area surrounding the aerodrome was earmarked for post-war suburban expansion. But, as noted above, the Great West Airfield, renamed Heathrow, had been given the mantle of London’s International Airport. The last scheduled flight from Croydon Airport was on 30 September 1959 and the airfield officially closed at 20.20 that evening.

Conclusion – December 1914.

When World War I was declared on Tuesday 4 August 1914, in Britain it was firmly believed that Germany would see sense and that any confrontation would be over by Christmas. As the months went by that belief began to wane but by November how to deal with the inevitable, deeply divided the British Cabinet. Nonetheless, they did agree to set up a War Council to direct the overall conduct of the War but what form this would take was contentious. The War Council consisted of Herbert Henry Asquith (1852 – 1928) Prime Minister (05.04.1908-05.12.1916), David Lloyd George, (1863-1945) Chancellor of the Exchequer (16.04.1908 – 25.05.1915 and Prime Minister from December 1916), Edward Grey, (1862-1933), Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (10.12.1905-10.12.1916), Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) Secretary of State for War (05.08.1914-05.06.1916) and Churchill the First Lord of the Admiralty (1911-1915).

According to George H. Cassar, in his 1994 book Asquith as War Leader (The Hambledon Press), they formed two groups, the ‘Westerners’, and the ‘Easterners’. The Westerners were headed by Asquith, who supported the military in believing that the key to victory lay in ever greater investment of soldiers and equipment on the Western Front in France and Belgium. While the Easterners, led by Churchill and Lloyd George, believed the Western Front was in a state of irreversible stagnation making the only chance of victory to be through action in the East. Asquith, as Prime Minister, held the key to the policy chosen and this not only dictated the initial strategy but also, in relation to this narrative, the development of British military aviation.

Although a number of airfields had been opened by both the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) since early 1914, powered aircraft was still considered a small part of the British armoury, particularly by some senior personnel in the army, headed by Lord Kitchener. The Military Wing of the RFC comprised of 147 officers, 1097 men and 179 aeroplanes, whereas the RNAS had 93 aircraft (aeroplanes and seaplanes), 6 airships, 2 balloons and 727 personnel. The Germans, on the other hand, had realised the value of aviation and in consequence their air force, made up of the military Luftstreitkräfte and the naval Marine-Fliegerabteilung, had 232 aeroplanes between them. Further, highly trained pilots who were expected to play an active part in the German fighting force flew their aeroplanes. By way of contrast, although both RFC and RNAS squadrons had actively shown themselves to be adept in aerial combat on the Western Front, directives were issued by the War Council, stipulating that pilots could only undertake reconnaissance and were only allowed to carry revolvers or automatic pistols for personal defence.

Others in the War Council, notably Churchill, did not agree and another directive was issued on 29 November 1914 announcing that the term Military Wing of the RFC was abolished. The Farnborough Squadrons Depot, Aircraft Park and Record Office were regrouped as the Administrative Wing, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Edward Bailey Ashmore, (1872-1953). They emphasised that the British military air fleet consisted of seven squadrons, the former RFC No 1 Squadron – an observation balloon squadron, made up of airships, had been transferred to the RNAS. The remaining squadrons were part of the RFC and at the outbreak of War, four RFC squadrons had been based at Dover’s Swingate aerodrome and when the RNAS opened a base in Dunkirk, 2 of those squadrons were sent there. The six squadrons had been divided into 2 ‘Wings’ of 3 squadrons each, commanded by a lieutenant colonel.

On 23 November, 6 days before the changes in the RFC directive was issued, all six squadrons had left from Swingate and Dunkirk and successfully bombarded the Belgium port of Zeebrugge. Using the occasion as an illustration, those in the War Council argued that British pilots, like their German counterparts, were capable of playing an active part in combat. It would seem that the position was not exactly resolved.

On 21 December 1914 a lone enemy plane flew over Dover and dropped a couple of bombs on the harbour before returning to the Continent. Three days later, at 11.00hours on 24 December, the first aerial bombing raid in the United Kingdom took place. The first landed in the garden of Thomas Achee Terson (1843-1936), of Leyburne Road, Dover, dropped by Lieutenant Alfred von Prondzynski. He was flying a Taube aeroplane and had been aiming to drop his bomb on the Castle. The blast broke an adjoining window and blew the St James Rectory gardener, James Banks, out of a tree though he was only slightly injured. There is a Dover Society plaque nearby, commemorating this event.

The next day, Christmas day, Royal Naval ships and submarines supported by seven RNAS seaplanes including some from Dover, battled against German Zeppelins, seaplanes and submarines. This was at Cuxhaven on the North Sea coast of Lower Saxony, Germany, some 30miles from the Kiel canal where the German surface naval fleet had remained in the harbour throughout the fracas. This was the first time that the British navy had used the combination of ships, seaplanes and submarines and it was also the first time that seaplanes were involved in combat.

Four years later, in the final year of the War, on 1 April 1918, the RNAS and the RFC merged to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). By the end of the War the RAF had become one of the United Kingdom’s three armed services. Their strength in November 1918 was nearly 300,000 officers and airmen, and more than 22,000 aircraft. At the Armistice, the French Aéronautique Militaire had some 3,222 front-line combat aircraft on the Western Front, making it the world’s largest air force at that time.

Always interesting, so much more going on than I realised. Thanksm D xxxx

>