Following the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918), Germany swept through Belgium routing the Belgian army. They then defeated the French at Charleroi and the British Expeditionary Force of 90,000 men at Mons, causing the entire Allied line in Belgium to retreat. Although the Germans planned to capture the French ports, the Belgians prevented this by flooding the region of the Yser River. However, by the end of 1914 both sides had established lines extending about 800-km (approximately 500 miles) from Switzerland to the North Sea. These lines were destined to remain almost stationary for the next three years.

The first German submarines appeared in the Channel around the middle of September 1914, sinking the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, off Zeebrugge. All three had men on board from Dover. Immediately after the Admiralty gave notice that a minefield was to be laid in the eastern entrance to the English Channel, between the East Goodwin Lightship and Ostend. The Scout, Attentive, was attacked by a U-boat (submarines) on 27 September and led to the withdrawal of the Scouts from patrol duties. They were replaced by the Dover Patrol whose objectives were:

– To maintain a safe passage of men and materials between England and France throughout the war;

– To lay and clear mines

– To check the cargoes of foreign merchant ships passing through the Dover Strait.

Having bases in both Dunkerque as well as Dover, the Patrol consisted of naval destroyers, small submarines drifters and requisitioned fishing vessels. The latter were manned by fishermen whose duty it was to trawl for German mines at the same time mines were laid as a protection against German submarines. Working closely with the Dover Patrol was the Royal Naval Seaplane Patrol based on the site of the former Guilford Battery, on the Seafront. In command of the Dover Forces in the Channel was Vice Admiral Horace Hood (1870-1916) who was given the order to stop U-boats passing down the Channel. Within a few months he was perceived as not being up to the task and was transferred out and replaced by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon (1863-1947). He ordered a Barrage – a huge net, with minefields on either side – to be strung across the Channel suspended from fishing boats and buoys.

Dover Patrol initially under the command of Rear Admiral Horace Hood (inset) courtesy of Doyle Collection

Regardless that the German offensive against British and Allied shipping continued, Admiral Bacon was convinced that the Barrage was working. Nonetheless, towards the end of 1916 about 300,000 tons of shipping was being destroyed monthly in the North Atlantic. Secret German documents revealed that the U-boats were passing down the Channel at night and on the surface, travelling over the Barrage and minefields.

In April 1917 about 875,000 tons of British and Allied shipping was destroyed and food shortages had led to the introduction of rationing. That month Coastal Motorboats, very fast motorboats armed with torpedoes, were introduced and on the night of 7-8 April, the Dover Patrol made a successful attack on Zeebrugge using them. After this, they were used along with the Motor-Launches that the Patrol had from the outset. These were armed with three-pounder guns and were used largely for convoying ships through the Channel. Vivian Elkington’s Dover Engineering Works was given the responsibility of maintaing the fleet. As the year progressed the German blockade was proving less effectives due to warships, depth bombing and hydroplanes to spot the U-boats. The Admiralty, however, felt that Admiral Bacon’s tactics were inadequate and Vice-Admiral Roger John Brownlow Keyes (1872-1945) replaced him on 31 December 1917.

At about the same time the British First Sea Lord, Sir John Jellicoe (1859-1935), was dismissed from his post but before going he proposed a raid on the Zeebrugge/ Ostend outlets from the Bruge U-boat base. Keyes was given the task of formulating the plan of action this was to sink block-ships in the canal leading to Bruge to prevent submarines getting out. Once approved it was agreed to attack the Zeebrugge outlet first. The harbour was, however, protected from the North Sea storms by a wall or Mole, stretching one and half miles into the sea. To inhibit a German offensive, while the operation was underway, a section of the Mole had to be destroyed. Once successfully completed, there would be a repeat attack on Ostend harbour thus trapping all the U-boats in the canals leading from Bruge to the Channel.

St George’s Day, 23 April 1918, was chosen for the raid on Zeebrugge harbour. The day before a special service was held at the Holy Trinity Church in the Pier District and was attended by Keyes, who was to command the mission from his flagship HMS Warwick. HMS Vindictive was the main cruiser, while commandeered Mersey ferries, Iris and Daffodil carried boarding parties. The flotilla also included 2 submarines, 34 motor-launches, 16 coastal motorboats and 10 assorted vessels. Three concrete-filled blockships, the Thetis, Intrepid and Iphigenia were to be sunk in the canal entrance, these were towed across the Channel.

Zeebrugge Harbour with the Mole in the background. In the foreground blockships in the entrance. Doyle collection

The convoy set off and once outside Zeebrugge burning chemicals were used to create a smoke screen. The blockships with the towboats were just off Zeebrugge when the wind changed direction clearing the smoke screen. Immediately the whole expedition came under heavy close-range fire. Then the prevailing current prevented Vindictive abutting the breakwater but Daffodil nudged her in. Men from the submarines blew up viaducts and the three blockships were scuttled. Zeebrugge was sealed!

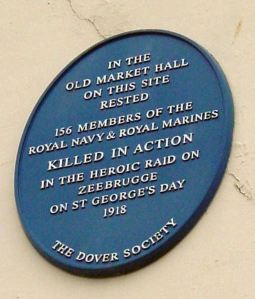

In recognition of the Zeebrugge Raid, 11 Victoria Crosses, 21 D.S.O’s, 29 D.S.C’s, 16 C.G.M.’s, 143 D.S.M.’s and 283 Mentions in Dispatches were awarded. However, out of the 1,700 men who went on the raid, 200 were killed and 400 wounded. Of those killed, 156 were brought back to Dover’s Market Hall, where volunteers assisted in sorting out the mangled bodies. Sixty-six of these men were buried at St James’ Cemetery. On the exterior wall of the museum, in the Market Square, is a Dover Society plaque commemorating those who died during the raid.

On 10 May 1918, the second part of the objective was put into operation, the Ostend Raid. This required the Vindictive to be sunk in the mouth of Ostend Harbour. Unfortunately, after another dramatic battle the Vindictive ran aground and only partially blocked the harbour. This meant that U-boats could still get out and attack allied shipping but the successful Zeebrugge Raid had slowed down the number of U-boats leaving the base. The last Dover Patrol vessel to be lost in that War was the drifter, Glen Boyne, on 4 January 1919. She was engaged in removing the mines from the Barrage when two men, John Bissett aged 32 and Edward Allen aged 18, were killed. The Lord Tilbury, a merchant ship, was the last vessel to be lost by war causes in the Channel; she hit a mine on 21 January 1919.

Before the War had ended Dover’s Mayor, Edwin Fairley, accepted from Vice-Admiral Keyes the Bell used by the Germans on Zeebrugge Mole to give warning of British attacks by sea and air. King Albert I (1909-1934) of Belgium had given it to the town in recognition of the Zeebrugge Raid. Initially, the Bell was placed in St Mary’s Church, but in 1921 it was moved the Maison Dieu and in 1923 placed in its present position at the front under a canopy. In 1933, the Bell briefly returned to St Mary’s Church for a special service broadcast on BBC radio.

Following the War a memorial was erected in the Holy Trinity Church, to those who had lost their lives but Vice-Admiral Keyes felt that there should be something more substantial in recognition of the members of the Dover Patrol. It was acknowledged that approximately 16million troops had been safely transported across the Channel due to the Dover Patrol but during that time, nearly 2000 men belonging to the Patrol had lost their lives. At first, it was agreed to erect a large cairn but nearly £45,000 was raised that meant three obelisks could be afforded.

Designed by Sir Aston Webb RA, the first was erected at Leathercote Point, St Margaret’s Bay, the foundation stone was laid by Prince Arthur of Connaught (1850-1942) on 19 November 1919 and the Memorial was unveiled by the Prince of Wales – later Edward VIII (1894-1972) on 27 July 1921. It was rededicated following World War II in memory of the Officers and Men of the Royal Navy and Merchant Navy who gave their lives in ships sailing in the Dover Strait. There is another obelisk at Cap Blanc Nez and a third at New York harbour in memory of the Dover Patrol’s French and American comrades. The Germans blew up the memorial at Cap Blanc Nez, but it was replaced in the late 1940s. In 2015, the Dover Patrol at St Margaret’s Bay was given Grade II Status.

On 5 November 1924, Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes unveiled Dover’s War Memorial. Afterwards the assembled dignitaries went to the Town Hall where Sir Roger presented the Dover Patrol Golden Book – the Book of Remembrance of the men who lost their lives serving in the Dover Patrol – to Sir Edwin Farley. This can be seen be seen at St Margaret of Antioch Church, St Margaret’s at Cliffe. The Rt. Rev, the Bishop of Dover, dedicated it on 27 December 1928. With the money left over a three-storey Dover Patrol Hostel was established on Wellesley Road. Lady Keyes opened the well-equipped establishment on 7 July 1923. However, during the Battle of Britain, on Wednesday 11 September 1940, Dover came in for heavy attack from about twenty bombers plus shells from across the Channel. A large calibre bomb hit the Hostel completely wrecking it, killing two and injuring many more.

Besides the obelisks and the Dover Patrol Book of Remembrance, a portion of one of the grapnels used on the Vindictive, can be seen in the small Garden of Remembrance, outside Maison Dieu House. It was originally mounted on the wall near the entrance gate of Leney’s Phoenix brewery in Castle Street. A casket made from the Vindictive was given to Lady Farley, the wife of the Mayor and in 2008 the original shrapnel damaged flag from the Vindictive was presented to Dover Town Council.

During World War I a junior officer serving with the Dover Patrol was Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945). In World War II (1939-1945) as Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay, he was in commanded of the Dover Station and from his headquarters in the tunnels beneath Dover Castle he organised the Dunkirk Evacuation.

Every year, including during World War II, Dover’s Mayor leads a special Dover Patrol Memorial service. This impressive ceremony takes place on the morning of 23 April.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury 19 April 2007