Between 26 May and 4 June 1940, 338,226 British and Allied troops were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk, France.

The town and port of Dover, together with many civilians, played a crucial part.

Following the German invasion of Poland, World War II (1939-1945), was declared on 3 September 1939 but there was no stopping Adolph Hitler’s (1889-1945) forces. By 21 May 1940, they were approaching Amiens, northern France, and advance attachments had reached Aisne. The previous day, (20 May) Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945), who had served with the Dover Patrol in World War I (1914-1918) was in command of the Dover Station. He attended a meeting to discuss ‘an emergency evacuation across the Channel by very large forces.’ His intention was to utilise the ports of Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne to evacuate 10,000 men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from each port every 24 hours.

Ramsay’s headquarters was the gallery in the tunnels below Dover Castle, cut by French prisoners of war in Napoleonic times (1793-1815) and housing a dynamo during WWI. The latter, it is popularly believed, gave the name Operation Dynamo to the Evacuation. Ramsay’s staff worked in adjacent rooms also cut in the chalk. The look out balcony facing the Channel can still be seen along with mock-ups of the rooms at that time.

On 22 May, the Germans captured Amiens, Arras and Abbeville and reached the coast despite the most desperate resistance. Throughout, they had used dive-bombers to clear away ground obstacles followed by vast numbers of tanks. The infantry followed light armoured cars and motor cycle units. In Dieppe harbour on 23 May, a stick of five bombs hit the 2,789-ton twin-screw Southern Railway’s cross-Channel ferry, Maid of Kent, which had been utilised as a hospital ship. The flames spread rapidly, killing and injuring many on board and reached a crowded hospital train alongside. Commandeered Belgium trawlers brought the survivors, including the Master of the Maid of Kent, Leonard Addenbrooke, to England.

Although the French were doing all they could to slow down the advance and Allied forces ceaselessly battered German communications, the forces kept on coming. On the night of 24 May, Boulogne fell and Calais quickly followed. British forces, along with French and Belgium comrades, had only one escape route, Dunkirk. On the 26 May, Operation Dynamo was put into action and it was later described, in an Admiralty communiqué, as the most, ‘extensive and difficult combined operation in British naval history…’

Dunkirk Evacuation 27 May – 3 June 1940, line of beleagured soldiers making their way to a waiting ship. Doyle Collection

Thousands of soldiers were stranded on the Dunkirk beaches but under Ramsay’s direction a fleet of 222 British naval vessels and 665 other craft, known later as the ‘Little Ships’, went to the rescue. The ‘Little Ships’ included, motor launches, pleasure boats, lifeboats, yachts, trawlers, drifters, tugs and paddle steamers, many handled by their civilian owners.

Mona’s Isle, an Isle of Man packet, was the first ship to make the round trip between Dover and Dunkirk but was bombed on leaving a beleaguered beach on 27 May. The 26-year-old Dover Harbour Board tug, the Lady Brassey along with Simla, another tug, went to her assistance. Under constant fire, the two tugs towed the ship, packed with troops, back to Dover. Two nights later, the same two tugs went to the help of the Montrose, which had been severely damaged off Dunkirk.

The 29 May saw 50,311 men rescued, 30 May, 53,227 and the peak day, 31 May 68,014 men were rescued with 34,484 landing at Dover. Twenty-five destroyers, sixteen motor yachts, fourteen drifters, fourteen minelayers, twelve transporters, twelve Dutch skoots, four hospital ships, and twenty-one assorted foreign vessels, including French and Belgium as well as British, were involved in the operation that day. On the final day of Operation Dynamo, the Air Sea Rescue and Marine Craft sections of the Royal Air Force, under constant fire, searched the Channel between the Goodwin Sands and Boulogne for survivors. They returned with thirty-five French troops and two British seamen.

Over the nine days of the Evacuation, 180,982 men were landed at Dover with just under 400 taken to what had been Buckland workhouse but for the purpose of the war converted into a casualty hospital. It was equipped with 110 beds and a massive under ground concrete bunker containing an operating theatre with two operating tables. A team of doctors including Dr. Gertrude Toland (1901-1985) carried out operations. Altogether, approximately 350 wounded were dealt with in the nine days and 300 survived. In addition, 108 bodies of men who had died on the ships before reaching safety were taken to the town’s Tower Street Mortuary, in the Pier District.

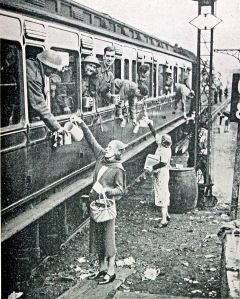

Dunkirk Troops being given food and drink enroute by train out of Dover – tired but cheerful. Doyle Collection

Lining up in Snargate Street, were EKRCC buses that took whole battalions of soldiers to destinations in Kent while some 327 trains took the survivors to locations throughout the country. On the journey the trains stopped at stations for about eight minutes so that women volunteers, working eight-hour shifts, could give food to the starving soldiers. 60,000lbs of bread a day were baked in ovens at Shorncliffe barracks, Folkestone, and private contractors provided another 50,000lbs. Men, at the barracks, made tea and cut sandwiches for 24 hours a day. Although there were initial problems, such as the tea being provided in china mugs, which broke when thrown from the carriage windows as the trains moved off! The cups were quickly replaced by tin cans fitted and paper cartons.Some 327 trains took the survivors to locations throughout the country. On the journey trains stopped at stations for about eight minutes so that women volunteers, working eight-hour shifts, could give food to the starving soldiers. 60,000lbs of bread a day were baked in ovens at Shorncliffe barracks, Folkestone, and private contractors provided another 50,000lbs. Men, at the barracks, made tea and cut sandwiches for 24 hours a day. Although there were initial problems, such as the tea being provided in china mugs, which broke when thrown from the carriage windows as the trains moved off! The cups were quickly replaced by tin cans fitted and paper cartons.

Throughout the Evacuation, the German aircraft were constantly over the Channel firing at the packed boats and ships. Mines had been strewn across the Strait so minesweepers were constantly at work in the dangerous task of sweeping. When they found and destroyed the mines, the explosions made houses rock in Dover. Many of the Little Ships were lost or seriously damaged along with Royal Naval vessels, Basilik, Grafton, Grenade, Havant, Keith and Wakeful.

In June 1957, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (1900-2002) unveiled a war memorial in Dunkirk (Dunkerque) to the soldiers who lost their lives while awaiting Evacuation and have no known graves. On Dover’s seafront, the Dunkirk Veterans’ Memorial was unveiled on Saturday 16 August 1975, by Major-General John Carpenter (1921-2009), to honour those who took part in the Evacuation. On behalf of the Town, the Mayor George Ruck, laid a wreath and a flypast salute was made by an Air Sea Rescue helicopter from RAF Manston.

Major-General Carpenter was a subalterton at Dunkirk in 1940 and in the early hours of 31 May he led his platoon on foot to the beach at Bray Dunes. As there wasn’t any ships he waded out and grabbed an abandoned lifeboat into which he crammed in his men. They were machine-gunned by enemy aircraft but were eventually picked up by a Dutch coaster and with only a few casualties returned to England. At the time of the unveiling of the plaque on Dover Seafront, Major General Carpenter was the chairman of the Dunkirk Veterans’ Association.

In St Mary’s Church, there is the Red Ensign of the ‘Fleet of Little Ships’. The flag was paraded through Paris when General de Gaulle (1890-1970), the French wartime leader, took the salute at the end of the War. There is also a window dedicated to all those who served in the Air Sea Rescue and Marine Craft sections of the Royal Air Force during World War II. It too was dedicated by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother when she was the Lord Warden (1978-2002).

For the maritime organisation of the withdrawal from Dunkirk, on 26 June 1940, Vice-Admiral Bertram Home Ramsay was awarded the Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath – Military (KCB) at Buckingham Palace. In 1944, as Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, he was given responsibility of organising Operation Neptune, the naval support for the D-Day Landings (6 June 1944). On 2 January 1945, the Admiral was killed in an air crash. A memorial statue of Admiral Ramsay was erected in Dover Castle grounds in November 2000.

The Southern Railway’s cross-Channel Ferry, Maid of Kent that was sunk at Dieppe on 23 May 1940 was later raised by the Germans and scuttled in deep water outside Dieppe harbour. Her bell was kept as a souvenir and found in a garage in Germany some years later. It was then returned to the British Railways Board, the successor to Southern Railways and hung in what had become Southern House – now Lord Warden House. The Bell now has a permanent home in the Dover Transport Museum, Whitfield.

The Isle of Man Post Office authority featured the Dunkirk Evacuation in 1981 to commemorate the diamond jubilee of the Royal British Legion. The stamp featured the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company’s ferry Tynwald outward bound for Dover, passing the sunken King Orry, which had been dive-bombed while taking troops on board. The Tynwald made her first trip to Dunkirk on 28 May 1940 and her last on 4 June. It is claimed she was the last ship to leave Dunkirk, by which time she had saved nearly 9,000 soldiers. The King Orry, while evacuating troops on 29 May, was badly damaged and sank near Ostend.

Rev. William (Bill) Purcell was in charge of St Mary’s Church at the time of the Dunkirk Evacuation kept a diary in the vestry book. On 25 May 1940, the day before the Evacuation started, he wrote, ‘The feeling of nightmare has been very strong these 15 terrific days. 15 days and Holland is conquered, Belgium and North France over-run the Germans in the Channel ports and 19 miles from this house, the BEF cut off and the Empire tottering. All of us waiting for bombs to drop, sirens to wail, parachute troops to invade us. Horror and inconceivable disaster on all sides. The sun has shone all the time, there is a hard drought, the spring is most beautiful. We can hear guns.’

Following the Evacuation, anti-invasion measures were frantically enhanced around Dover but by the 22 June, France had surrendered and on 10 July, the Battle of Britain began.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 27 May 2010