On 19 August 1921, the Railways Act received Royal Assent that proscribed all the railway companies, which were in private hands, to merge into four ‘Groups’. One of these was the Southern Railway Company and was made up of railway companies that operated south of the Thames. These included the two companies that served Dover – South Eastern Railway Company, which used the line through Shakespeare Tunnel to the then Town Station and Marine Station, at Western docks; and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company, which went to the Marine Station via Priory Station and Harbour Station.

Southern Railway came into operation on 1 January 1923 and although subject of intensive discussions, legal threats and counter threats within the company, as far as Dover was concerned the amalgamation did not cause much of a stir. Possibly because the two railway companies serving Dover had semi-amalgamated on 1st January 1899 to form the South Eastern and Chatham Railway Companies Management Committee (SECR).

The Re-Grouping of the railway companies had been seriously considered since World War I when the logistical needs of government had effectively nationalised the system. Although the individual railway companies had been returned to private ownership, shortages and lack of maintenance had taken their toll.

Brigadier-General Sir Hugh Drummond was appointed Chairman of the new company, but died on 1 August 1924 being succeeded by Brigadier-General the Hon. Everard Baring. At the outset, three joint General Managers were appointed one of whom was Sir Herbert Walker, the other two resigning before the year was out.

For administrative purposes, Southern was divided into three sectors and Dover became the headquarters of the Eastern section. Preparations had already been taken place to convert part of the old Town station, to the west of the Lord Warden Hotel, into offices. From there, 744 miles of railway would be controlled by the operations staff headed by a Traffic Manager.

Under the Traffic Manager were specialist Superintendents one of which, at Dover, was William Reginald Busbridge. From the early days of the SECR, he had held the position of Chief Assistant Superintendent for the area. Highly thought of by the Company and his work mates, he was awarded the MBE in 1934 but died the following year. He lived at Gresham Villa, Priory Hill.

The position of Chief Mechanical Engineer was given to a former employee of the SECR, Richard Maunsell (1868-1944). The rolling stock was inherited from constituent companies and Maunsell, on appointment, began the standardisation of the inherited railway lines. Although these were of a standard gauge, they varied in the types of rails, fastenings and so on. The new company also inherited 135 different types of locomotives. These he either had modified or replaced as soon as possible along with the rolling stock painted in the Southern’s livery of olive green with gold lettering. The Works, for the Eastern section, was at Ashford and again inherited from the SECR.

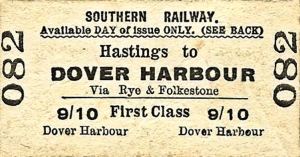

The company had also inherited many different types of carriages; these Maunsell eventually replaced with a standard design of carriage based on the former London and South Western Railway’s Ironclad. They were classified between 0 and 4 to tally with the width restriction of the line they were to be used on, an 8 feet 0¾-inch wide carriage equalled ‘Restriction 0’ – ideal for the then heavily restricted section between Tunbridge Wells and Battle. Southern reduced the number of passenger classes of carriages to First and Third. Second class compartments were withdrawn except for trains designated as ‘Continental’ on the London-Dover lines.

For logistical and maintenance purposes, the carriages were marshalled into fixed numbered sets with reserve carriages kept in case of breakdowns and to deal with increases in passenger numbers, such as holiday periods. Although Southern Railway catered mainly for passengers, they did have their own freight wagons and at one point boasted of 37,500. These were mainly four-wheeled and painted dark brown with white ‘SR’ on the side. Luggage carriers attached to boat trains had four-wheeled bogies.

Southern also inherited all the railway stations and related activities such as hotels including Dover’s Lord Warden Hotel, and a fleet of ships. The Maritime subsidiary, branded as Channel Packet, included a number of ships based at Dover. These were the Canterbury – steel twin screw passenger and cargo steamer that had arrived in Dover from the Clyde 30 January 1901; Invicta – Steel twin screw turbine steamer launched 21 April 1905; Victoria – Steel triple screw passenger and cargo steamer launched 6 March 1907; Empress, steel triple screw turbine steamer launched 12 April 1907; Biarritz– Steel twin screw passenger and cargo steamer launched 7 December 1914; Maid of Orleans – Steel twin screw passenger and cargo steamer launched 4 March 1918.

With them, Southern had inherited the contract for carrying Mail to and from the Continent. Both the Invicta and the Empress were sold to the French in 1923 but still worked the Passage until 1933 when they were scrapped.

At the time, Davison Alexander Dalziel (1854-1928) was chairman of the International Sleeping Car Share Trust Ltd, better known as Wagons-Lits. It is general accepted that Dalzeil put forward the notion of Southern’s Continental Express boat train that was introduced on 14 November 1924. Designed to be the height of luxury, it consisted of six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and a brake van. Like all boat trains to Dover, the London terminus was Victoria Station and the luxurious Continental Express left at 10.50hrs connecting with a packet ship at Dover and the return Continental Express train left Dover for London at 17.30hrs.

Some members of the fledgling company’s board had grand ideas that included building a Channel Tunnel to replace the ferry services. This, the government of the day was not so enthusiastic, so a combination of rationalisation and upgrading of the ferry services took place. The number of Channel crossings was reduced from the pre-war nine, to seven and the night boat between Dover and Boulogne was axed.

Among Maunsell’s many innovations was the introduction of ‘class’ to locomotives. In 1925, he introduced the King Arthur class, an advance on the R.W.Urie designs for the London South Western Railway. Each locomotive named after a character from the court at Camelot. The carriages were Pullman and the name of the locomotive was in polished brass, as were the number plates, and their background was either red or black. A King Arthur class engine was used for the Continental Express.

At the Company meeting of February 1925, Southern’s Board passed a covetous eye over the Port of Dover, telling shareholders that it would be in the best interests of the Port if it came under their control. Locally, many of the influential agreed citing Southampton docks, already controlled by Southern, as an excellent example.

They also announced that the Biarritz and the Maid of Orleans were to be refitted during the winter of 1925/26, converted from coal to oil and on return to be based at Folkestone. The Dover crossing was to have two new ships, Isle of Thanet and Maid of Kent. Both were steel twin-screw turbine steamers built by Denny’s of Dumbarton and the Isle of Thanet was launched on 23 April 1925, the Maid of Kent on 5 August that year. They were provided with Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers, oil-instead of coal-fired. The Isle of Thanet made her inaugural voyage to Calais on 24 July; however, in November that year she was transferred to Folkestone for the Boulogne passage.

The Maid of Kent arrived in Dover on 28 October and took over from the Isle of Thanet. However, on 9 March 1926 and again on 13 February 1927, the ship struck blockships, left over from World War I, in the western entrance. Calls had already been made to close the entrance permanently and the accidents reinforced the decision, but it never became a reality.

By this time Southern had introduced the first professional Public Relations department on the railway network. Under the influence of John Elliot (1898-1988), it was instrumental in creating the positive image for both the company and the places it served. Elliot, knighted in 1954, introduced special excursions, typically on Wednesday 1 June 1927, a Derby Day train to Tattenham Corner, leaving Dover at 09.25hrs and costing each passenger 10-shillings (50p). He also initiated the ‘South for Sunshine’ campaign, taking passengers to the ‘finest resorts in the World’, these included Dover.

Further, as far as Dover was concerned, and besides taking over the port and closing the Western entrance, the Company was interested in the boat trains and the coal industry. In 1926 Maunsell introduced what were the most powerful 4-6-0 locomotives of the time – the Lord Nelson class – for the London-Dover boat trains. The tractive effort was 33,510-lb.

The price of imported coal from the Continent was at an all time low, Southern was exploiting the situation through their monopoly of carriage from the south coast ports, including Dover. Indeed, in 1926 they sold the Canterbury when more cargo carrying tonnage was deemed necessary. However, the Government in 1925 attempted to combat the rising coal imports by, amongst other things, increasing investment in the Kent coalfield.

In February 1926 Southern took up unissued capital of the East Kent Light Railway Company (EKLR) and invested some £300,000 on the line. In the spring of 1926, due to strong sterling the price of imported coal continued to fall that led to a cut in the number of miners needed and for those who did have work, their wages. The General Strike began at midnight on 3-4 May 1926 and a State of Emergency was declared. Southern’s railway men came out in support of the miners. Although the national strike ended on Wednesday 12 May but it was not until the Friday that Southern agreed to the men resuming work.

Back on 18 October 1923 members of Southern’s Board met Dover Corporation to discuss reconstruction of Priory Station, based on plans agreed with SECR prior to Grouping. The work was estimated at £125,000 and included a new railway bridge on the Folkestone Road. The following 24 June, at another meeting with Dover Corporation, the Company announced that they planned a new engine depot, marshalling yards, goods yard and the rebuilding of the Customs sheds on the West Quay, near Marine Station as well as laying a double track past Archcliffe Fort. Besides costs, the first would require the demolition of Harbour Station and the latter, the demolition of the 50-yard (45.7 metre) tunnel that ran under the sea side of the Fort. This would require parliamentary approval and the estimated cost was £250,000.

Permission was granted and demolition began in October 1926. During the removal of part of the original Fort, two intact skeletons were found. Locally, they were believed to be pirates that had been hung and then interred. As part of the parliamentary approval, it was agreed to replace what had been a pathway from the station area to the block yard used for construction of the harbour as well as the station. It was envisaged that the new road would make a ‘nice seaside promenade’ along what was then called the Western Beach, later renamed Shakespeare Beach.

The weather in 1927 was noted for being particularly wet. On the morning of 24 August, there were three heavier than normal thunderstorms in the vicinity of Sevenoaks and the ground was waterlogged. The 17.00hrs Cannon Street to Deal Express pulled by the River Cray, River Class engine was derailed causing several of the carriages to smash against the supports of a bridge and thirteen passengers were killed.

A significant number of passengers came from Dover, one of whom, Miss Helen Hatton of 4 Pencester Road lost her life. Leslie Parfitt, a young boy from Sutton, near Dover, was also killed and four of his family injured. Other Dover people injured included Mrs Hatton and another daughter, Constance, Mr and Mrs Alfred Leney and a Miss Pipe. An inquiry undertaken by the Ministry of Transport blamed both the waterlogged track and the River Class engines, which were withdrawn and then re-built as tender engines.

Prior to the 1926 General Strike, Richard Tilden Smith had bought Tilmanstone Colliery, which he planned would be the centre of an Industrial Eden in East Kent. Southern, on the other hand, saw the pit as a lucrative source of income, as the coal would have to be transported on the EKLR, so they could set the price. Tilden Smith, in response, applied to the Railway and Canal Commission to build an aerial ropeway from his colliery to what was then known as the Eastern Dockyard. There, Dover Harbour Board had already planned, in conjunction with Southern Railway, to build two coal staithes for bunkering coal-fired ships at an estimated cost of £35,000. In March 1927, the Commission turned Tilden Smith’s application down but following a legal battle, permission was granted and work started on his aerial ropeway in the autumn of 1928.

Southern were slow to recognise the growth in car travel and made little effort to accommodate passengers who wished to take their car across the Channel. At the same time, they charged exorbitant prices and demanded that the petrol tanks were to be empty, forcing owners to dump fuel into the harbour. Captain Stuart Townsend, formerly of the Honourable Artillery Company, found this irritating but was incensed when his vehicle was damaged during a crossing.

In 1928,he chartered Artificer, a 272-tons gross collier, to carry cars across the Channel for the summer season commencing in early July. Dover Harbour Board gave him permission to use the Camber at the Eastern dockyard and charging approximately half the rate of that of Southern’s, he carried up to 15 cars and 12 drivers per crossing. A crane was used to lift the vehicles on and off the ship.

The following year Captain Townsend increased his capacity with the replacement ship Royal Firth, 411-tons gross and then by the ex-naval vessel, Forde, which carried 307 passengers and 26 cars each crossing. Southern responded with the steel twin-screw steamer Autocarrier launched 5 February 1931 making her maiden voyage to Calais on 26 March. She carried the same number of passengers and cars and like the Townsend ships, vehicles had to be craned aboard. Nonetheless, the Autocarrier was Britain’s first railway owned cross Channel car ferry. She only operated as a car ferry in the summer and in the winter covered the Folkestone – Boulogne passage.

About the time Autocarrier was ordered Southern sold the Victoria to the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company and introduced the Golden Arrow service. Offering super-class travel from London to the Continent, the Golden Arrow made its first through journey on 15 May 1929. The train consisted of 10 Pullman cars and luggage vans, hauled by a 4-6-0 Lord Nelson Class engine sporting the Union Flag and French Tricolour. The carriages were individually named, resplendent in chocolate and cream and boasted of the first public address system on a train.

The French, in September 1926 had followed Southern’s lead over the Continental Express and launched an all-Pullman train between Paris and Calais, giving it the title of Fléche d’Or. To take passengers across the Channel, connecting the two luxury trains, Southern had ordered the Canterbury. A steel twin-screw turbine steamer built by Denny’s of Dumbarton she was launched on 13 December 1928 and arrived in Dover on 29 April 1929, making her maiden voyage on the same day as the first Golden Arrow from London. The journey between London and Paris was advertised to take 6½ hours.

Partial demolition of Harbour Station was completed by June 1929 when the ferry captains put forward the case for keeping the clock tower as it provided an excellent leading line. The tower was reduced in size, a light fixed and it was decided to keep the connecting building. This was sold on 27 July 1984 and in August 2002, P&O gained full possession of the Harbour Station by which time the building was Listed. The bonded warehouse, during Southern Railways tenure, was part of the original building until they moved the stock to what became known as the ‘Champagne Caves’ on Limekiln Street.

The London commuter lines, south of the Thames, were, and still are, the most lucrative for Southern and in September 1929 saw major modernisation by replacing AC overhead electrification with 660-volts third rail (now 750) DC. However, the rolling stock comprised of converted steam-hauled carriages. Nonetheless, by the end of that year the Company boasted of operating 2771/2 route miles (447 km) of 3rd rail electrified track. During 1929, the Company again proposed the building of a Channel Tunnel but once again, the Government rejected this.

In February 1928, Southern Railway submitted a Parliamentary Bill to enable the company to provide and work road vehicles in any district to which access is afforded by its system for the conveyance by road of passengers, their luggage, goods and livestock, and to apply its funds for the purpose. The Bill also sought to enable the company to enter working relations with Local Authorities, companies or persons owning or running road transport services. By August that year Southern Railway had acquired 49% of the shares in the East Kent Road Car Company and came to an arrangement with the Post Office to carry parcels.

The Southern Railway Bill was opposed by Dover Corporation but withdrawn and the Bill was given Royal Assent on 3 August 1928. In 1929 Southern introduced a fleet of goods vehicles providing a door-to-door delivery service tying the service in with their rail services. Using Conflat-type wagons, they could carry containers by rail and road to the delivery address. They introduce the Kent Fruit service for the soft fruit market in July 1932 enabling fruit, beginning with cherries, to arrive in time for an early market in northern and midland towns. In 1934, they expanded this part of their business further when they acquired Pickford’s haulage and removal company.

However, on 24 October 1929, thirteen million shares changed hands on the New York Stock Exchange that led to its crash. This was followed by a severe world-wide economic depression. As a result Southern closed its divisional offices at Dover Town Station laying off 90 staff. Much of the Station was subsequently demolished to make way for a turntable that enabled one man to turn a heavy locomotive for the return journey to London.

The rebuilding of Priory Station had still not taken place but the Company managed to see its way clear to give authorisation. The western platform was roofed over and Messrs Rice and Sons built station buildings on the eastern side. The Goods Yard was transferred to the western side, with an entrance and office in St. John’s Road. The station was opened on 8 May and the Goods Yard on 20 May 1931.

At the end of 1930, the catering contract for the Eastern and Western sections of Southern Railway was given to Frederick Hotels Limited. The previous holders had been Spiers and Pond who pioneered railway catering in the UK. Frederick Hotels had been providing the catering on the ferries and was also running the Lord Warden Hotel.

Dover Harbour Board’s proposal of a coal staithe at the Eastern dockyard remained on track. Southern, along with Messrs Pearson and Dorman Long, the owners of Snowdown and Betteshanger Collieries, were more than interested and proposed to build the staithe. Tilden Smith’s 7.5 mile (11 kilometres) long aerial ropeway from Tilmanstone colliery to the Eastern Arm was completed in 1930 and was capable of carrying up to 120-tons of coal an hour in each bucket had the capacity if 16-hundredweight. Tilden Smith had died and all parties agreed that a 5,000-ton coalbunker would be built.

When Tilden Smith’s giant coal staithe was almost ready, Southern Railway and Pearson Dorman Long, who owned Snowdown and Betteshanger collieries, through DHB, asked for the staithe to be altered. They wanted a lower staithe constructed and to use the giant staithe’s loading facilities but Tilden Smith refused. Coal, up to that time, had been unloaded at Western docks but due to passenger trains using Marine Station and goods trains using the Wellington and Granville Docks, congestion was a major problem. In 1918, the Admiralty had built the Sea Front Railway, using rails from the Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Light Railway that ran over the cliffs to the Eastern dockyard in order to transport war material to the Camber.

Seafront Railway c 1955 adjacent to Waterloo Crescent No 31027 a P-class 0-6-0 tank-engine. Dover Museum

The railway was handed over to Dover Harbour Board and Southern Railway in 1923, as a joint operation, and they had used it for carrying fuel oil once a day. It seemed natural to use this Railway to carry coal from Western Docks to the Eastern Arm and together with the coal brought in by the aerial ropeway justified them using the large coal staithe. Over this, Tilden Smith had refused but in 1931 Southern Railway paid to have a low coal staithe built adjacent to Tilden Smith’s giant staithe.

Southern’s staithe was designed to take ten hours to load 5,000 tons of coal and cost £22,000. The first ship to be loaded was the Kenneth Hawksfield that took on board 2,400-tons from Snowdown Colliery on 19 April 1932. Southern anticipated using the track 14 hours a day and to carry 800,000-tons of coal a year along with scrap iron and oil for refuelling ships. The first coal train ran on 15 April 1932 choking its course with smoke and dust. 17,000 Dovorians signed a petition that was sent to the House of Lords, and Parliament restricted the Sea Front Railway to carrying 300,000 tons of coal a year but this, argued Southern, was not viable and they were dropping the idea but in reality did not do so.

The economic depression hit the Golden Arrow bookings such that on 15 May 1932 the service was extended to Second class passengers. However, the French in 1931 introduced the Côte d’Azur and in 1933 the Côte d’Argent to the Channel passage. Both ships were similar to the Isle of Thanet and the Canterbury. The last two ships inherited from SECR, the Empressand Invicta, were declared redundant and scrapped.

Maunsell had introduced the School’s Class in 1930 to the Southern locomotive fleet. This was a 4-4-0 passenger express and all 40 engines were named after English public schools. On 28 March 1933, number 911 was Dover, named after Dover College, made her first visit to the town. The class operated until 1961 though three are still preserved on heritage railways in Britain.

Following the success of the 1928 Parliamentary Bill, Southern Railway, along with the Great Western Railway and the London Midland & Scottish Railway, sought powers to undertake air transport. This was to provide rapid transportation and to meet emergencies such as those brought about by the General Strike of 1926. The Act was passed but it was not until 1933 that Southern Railway employed consultants Airwork Services run by Air Vice Marshall Sir Henry “Nigel” Norman (1897-1943) and Alan Muntz (1899-1985), with architect Graham Dawbarn (1893-1976) to look into possibilities. Throughout the consultants liaised with a junior officer within the railway company, Leslie Harrington (1906-1993) who later lived at Marine Court, on Dover’s seafront.

The report noted that besides Channel packet ships, ocean going and coal carrying ships were increasingly using the harbour. However, there were physical problems of using the harbour as a seaplane base. On the north-east side were/are cliffs and along the Eastern Arm was the Tilmanstone Colliery aerial ropeway, which could be a liability. The harbour was notorious for its major negative tidal and wind effects and although the Channel Air Express, owned by Air France, did offer a service, the previous summer it had only operated 50 flights and hardly operated any during the winter.

Albeit, as the economy recovered, the report said, people may prefer to fly across the Channel and reclaim their cars transported by ferries, on the other side. An alternative splendid site for such an operation, they suggested, was the former Swingate aerodrome owned by the Ministry of Defence. Although, part of the site was rented out to a golf club it might be made available for civil aviation. The report also mentioned a landing field at Whitfield 3½ miles to the north of the harbour but the schemes never put into action. By the time the report was published Harrington had moved on becoming the Marine Manager at Dover and rising through the ranks of Southern Railways and its successors, he retired in 1969 as British Rail General Manager of the Shipping & International Services Division.

Due to repeated landslips on the line between Folkestone and Dover, Southern successfully applied to Parliament, in 1934, to build a 4-mile loop from the main line at Folkestone to 557-yards east of Abbots Cliff tunnel but was never laid. October 1934 saw the Southern Railway Marine Department Divisional Offices move from Admiralty House, on Marine Parade, to a suite of offices in what remained of the old Town Station. The station was finally demolished in February 1963.

On July 17 1934, the Twickenham Ferry, the first of three steel twin-screw turbine steamers for the new railway-ferry service from Dover to Dunkirk, arrived at the Port.

In the first week of December 1931, Southern had given notice that they were going to promote a Parliamentary Bill, the main feature of which would be a new train ferry dock at the South Pier. In August 1933 start was made on the concrete dock, 415-feet long and 72-feet wide, and having a depth of water from a minimum of 17-feet to a maximum of 36-feet.

Using powerful pumps and specially designed dock gates the water level was raised or lowered so that the ferry in the dock was quickly brought to the required berthing level whatever the water level outside. Two branch lines linked with the main line and the trains were put on board the ferry over an electrically operated lifting bridge, or link span, that connected the ship and the shore. John Mowlem & Co along with Edmund Nuttal, Sons & Co built the dock.

Twickenham Ferry twin-screw, 2,839 tons gross, built as part of Southern Railways train-ferry fleet.

The specially built ferries were ordered from Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, Newcastle-on-Tyne and were the Twickenham, Hampton and Shepperton, 2,839 gross tons each, coal-fired and had an average speed of 15 knots. The length was 359-foot; 63-foot 9-inch beam and 12-foot 6-inches draft. Each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars, 500 passengers during the day, or approximately 40 goods wagons. There was also a small floor above the train deck to accommodate approximately 20 cars. The formal opening of the service took place on Monday 12 October 1934 and included an official crossing to Calais and back with many distinguished guests on board.

On 5 October 1936, a night service between London and Paris was introduced. Featuring newly constructed, blue liveried, sleeping coaches from the French, Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits leading to the nickname Blue Train. Adapted for the British loading gauge, each overnight train carried up to five and occasionally six, sleeping cars and because of their weight, the train was double-headed.

The train left Victoria Station at 22.00hrs with the passengers remaining undisturbed for the whole journey until arriving in Paris at 08.55hrs the following day. The counterpart left Paris for London and there was a daily goods service via the ferry, which allowed the commodities being consigned to and from any part of the Continent without transhipment. The service used the Hampton, Shepperton and Twickenham ferries and their successors.

Earlier in the year, on 25 – 26 January 1936, Southern ran 7 extra continental ferries, 10 special trains and 13 special coaches to carry crowned heads of Europe and senior dignitaries to London for the funeral of King George V. The majority of the traffic came through Dover. On 31 December 1936 the Dover tram service, run by the Corporation gave way to a bus service operated by East Kent Road Car Ltd. The contract was lucrative to both parties; further, the bus company had a long-standing working agreement with Southern Railways. Later that year, the Twickenham Ferry was sold to the Société de Navigation Angleterre-Lorraine-Alsace for £150,000 and re-registered in Dunkirk under the same name and colours.

1937 saw major changes at the top of Southern’s management structure, Sir Herbert Walker retired and was replaced by Gilbert Szlumper. He stayed until the outbreak of war when he was recalled by the War Office and was succeeded by Sir Eustace Missenden who remained in post up until Railway Nationalisation. Richard Maunsell also retired and was succeeded by the innovator, Oliver Bulleid, nicknamed the ‘Last Giant of Steam’.

Bulleid made a number of meritorious changes to the establish designs of locomotives, for instance, welded steel boilers and fireboxes that were easier to repair. He replaced the traditional spoked wheels with those of the boxpok type, made up of hollow box sections that provided better and more even support of the tyres. The livery was also changed to Malachite green, a blue/green. The lettering as well as other aspects of the locomotive were painted bright yellow. For the duration of the war, only the colour of lettering remained high lighted with Malachite green, the rest of the stock was matt black. Following the War the livery was reinstated using gloss paint.

A further change took place on 28 June 1937 when a ramp replaced the crane for getting road vehicles on and off the Dover-Dunkirk ferries. There was room for 25 cars housed in a steel garage and drivers were now allowed to leave petrol in the tanks. The first car to use the service, which was on the Shepperton Ferry, was an 1898 Benz and the passengers included Alderman George Norman, Mayor of Dover and General Manager Szlumper.

Railway services from and to Dover, according to a 1938 advert included:

- Special pullman trains

- Through services run in conjunction with other Railways from all parts of the British Isles

- Daily, weekly and monthly return discount tickets

- 7 day season tickets enabling passengers to travel when, where and as often as they like within a specified area for one week.

Of note, a railway company recently (2013) seeking further franchise operation deplored such services, saying: ‘regional managers had a considerable degree of latitude when setting local fares … (they created) a patchwork of fares that did not necessarily reflect passenger volumes from individual stations or market conditions.’

Tenders were invited in January 1939 for a new ferry to take the place of the Canterbury and the order was given to Southern’s favourite contractor, Denny’s of Dumbarton. A steel twin-screw turbine steamer, the Invicta, as she was named was launched April 1940 and immediately commandeered by the Admiralty for war service.

Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain together with Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary, travelled by way of Dover, on the Golden Arrow then the Canterbury, for Rome on 14 January 1939. This was to meet with Benito Mussolini, Italian political leader in an effort to persuade him not to become involved in the pending conflict. Marine Manager at Dover, Leslie Harrington, conducted the party across the Channel. As Harrington was seeing them off at Calais, Chamberlain turned to him and whispered ‘ Young man, haven’t you forgotten something? … My umberella.’ The Prime Minister had left it in his cabin and would not be seen in public without the umberella! The port of Dover was closed on 5 September 1939 and the Marine Station was pressed into military service and utilised for the movement of troops belonging to the British Expeditionary Force.

Southern was well equipped to carry passenger traffic, which was 75% of its rail load. As the war progressed although the number of passengers carried was on average the same, the amount of freight increased significantly eventually making up 60% of the rail load. This Oliver Bulleid, with his customary innovations dealt with.

Two days after War was declared all civilian cross-Channel traffic diverted to Folkestone where the normal service was continued. Only authorised vessels were allowed to enter Dover. The Canterbury, in September 1939, was converted into a troop carrier and the Hampton and Shepperton into minelayers. The Twickenham manage to escape from France and operated between Stranraer and Larne under the auspices of the Admiralty. The Maid of Kent was converted into a hospital ship but on 23 May 1940, as wounded soldiers were being loaded at Dieppe, a designated hospital port, she was bombed and sank with the loss of 28 merchant crew and medical staff.

Later in the War, the Germans moved the wreckage to deeper water but her bell was rescued. After the War, the proprietor of a garage in Germany gave the bell to the Nationalised Southern Railway and it was hung in Southern House, as the Lord Warden Hotel was then called. It can now be seen in the Dover Transport Museum.

Up until May 1940, it was smartly attired troops who were being carried through Dover to the ferries to take them to the Continent. In May 1940, the scene changed dramatically to that of dirty, bedraggled exhausted troops being brought back from the beaches of Dunkirk. On peak days, some 60,000 men boarded special trains. All told nearly 200,000 British and Allied troops passed through Dover.

The Isle of Thanet was the first hospital ship to go into Dunkirk and made several trips. The Autocarrier, Biarritz, Canterbury, Hampton Ferry, Maid of Orleans, Shepperton Ferry, also rescued thousands of troops and all these ships came under heavy bombardment. The Canterbury was badly battered on while standing off the Mole at Dunkirk, on reaching Dover was hastily repaired and returned to pick up more troops. It was reported that the Maid of Orleans with so packed with troops that they were standing shoulder to shoulder, was attacked by five planes. When she arrived in Dover, it was reported that ‘blood was running down her sides.’ The Dinard was also there, a Southern ship that after the War returned to Dover to work the passage.

On 12 May, during the evacuation, the town and port was declared a ‘Protected Area’ and following the evacuation Marine Station was ‘closed’. All trains and stations, by this time, were subject to the blackout. Station names were removed so passengers had to rely on a porter shouting out the name. At night, as most station lights were sprayed with blue paint, platforms were ghostly lit and even that was extinguished when the air raid warning was sounded.

As the war progressed, carriages were fitted with a special white light as long as the window blinds ensured complete black out and even then, these would be turned off during an air alert. Nonetheless, the bright shiny railway lines were beacons to enemy aircraft and were subject to constant attacks. The glow of the firebox, that identified locomotives as targets, was dealt with by hanging heavy storm sheets over the cab. However, the white smoke from the chimney remained an intractable give away.

Railway lines were used for artillery purposes by the Germans and caused havoc on British convoys passing through the Dover Strait. Static guns were installed along with three13.5-inch calibre railway guns manned by the Royal Marines and called Gladiator, Piecemaker and Sceneshifter. All three guns were survivors of World War I and were hauled by diesel engines. During periods of inaction the guns were normally hidden in Guston tunnel but sometimes in tunnels at Shepherdswell and Martin Mill.

On Sunday 2 June 1940, 2,899 local children, teachers and helpers left Dover Priory Station to be evacuated to Monmouthshire in Wales. The first train left at about 07.45hrs and the fourth, and last train left at 12.40hrs but it was estimated that between 800 and 1000 children remained in the town. The Battle of Britain started on 19 July 1940 and the town and harbour quickly earned the name ‘Hell Fire Corner’. The network of railway tunnels around Dover was used to keep rolling stock, railway workers and passengers’ safe.

During the night of 11 September 1940, a bomb exploded near the entrance to the Priory goods yard killing gas company employee, Home Guard, Fred Haywood. The footbridge over the station was also demolished that day. The signal office at the station was hit by a shell on 25 October injuring six, one of whom was Assistant Linesman Arthur Lyus aged 29, who later died in hospital.

Although the Battle of Britain was over, the Priory Station came in for another shell attack on 1 November. In June 1941, Marine Station was ‘opened’ to military traffic going to the Second Front following Germany’s invasion of Russia. In October that year dive-bombers badly damaged Priory Station but on Good Friday the following year, the bombers missed the station and demolished two houses in nearby Priory Gate Road killing two and injuring eight.

1941 saw the introduction of Bulleid’s powerful Merchant Navy Class, all-welded boiler, chain-driven valve-gear, and air smooth casing with a tractive effort = 37,515-lb. Each was named after a famous shipping company and were particularly useful at moving heavy wartime freight. The Q-1 Class, also designed by Bulleid was introduced that year. With its large, squat chimney, flat-topped dome and devoid of a footplate and wheel splashers, the Class was nicknamed Austerity!

On 19 August 1942 Operation Jubilee or the Dieppe Raid, as it is better known, took place. 6,086 commandos, mainly Canadians, were deployed to investigate the extent of the German defences. One of the troop carriers taking part was the Invicta. 60% of those who made it ashore were killed, wounded, or captured.

The railway lines and stations were under constant attack throughout the War and many of the repairs were carried out by the Home Guard – off duty railwaymen. When on duty they would be manning stations, driving trains or carrying out wagon and carriage maintenance or repairs. The battered Priory Station still functioned and on 23 October 1942, it was the scene of lasting historical interest when South African Prime Minister, Field Marshall Smuts, visited the town accompanied by regular visitor, the Prime Minister Winston Churchill. They inspected some 130 representatives of the Civil Defence Services.

7 February 1944 was the centenary of South Eastern Railway reaching Dover and Southern put on an exhibition of historic prints and records at the Town Hall. The luncheon was attended by the Chairman of the Southern, Sir Eustace Missenden.

Spring 1944 saw increased activity in preparation for the D-Day landings and the need to fool the Germans that the landing would be in the Pas de Calais. At the same time as D-Day – 6 June – drew near ‘real’ preparations were underway. Southern ships taking part in the landings included Biarritz, Canterbury, Invicta, Isle of Thanet, and Maid of Orleans. The Isle of Thanet was the deputy HQ ship of Force J commanded by Admiral Vian, however, converted troop carrier, the Maid of Orleans, after making several trips to the beaches hit a mine on 28 June and sank off St. Catherine’s Point, Isle of Wight. Five crew members were lost. After the explosion, the Master and four Officers remained on board one of which was Cyril Robert Cubitt, Chief Engineer, who was awarded for rescuing a brother Officer.

In Dover, on 7 June, Southern’s Loco Shed near Marine Station received a direct hit seriously injuring Henry Whitewood, aged 60, who died a week later. As troops drew nearer to Calais, the attacks on the town became more intense. On Wednesday 13 September, just as a train arrived at the Priory, nine-year-old Frederick Spinner, Mrs Julie Green 61, two servicemen and an ATS girl were killed during a shell attack. The Marine Station came in for sustained shelling and on 25 September, it was all but destroyed.

Following D-Day, the Train Ferry Dock became a hive of activity and on 29 June 1944 the Twickenham, with a large gantry, protruding over the stern and carrying a transporter crane capable of carrying 84 tons, delivered the first load of British-built locomotives to the Continent. Both the Hampton and Shepperton, similarly adapted, joined their sister ship in transporting engines to Calais and Boulogne. When the War in Europe ended, British and Allied troops returned for demobilisation leave on Southern ferries. Some of these men were sent to makeshift camps in and around Dover but most were sent to London and beyond. Often there were thirty full trains a day carrying returning troops.

On 18 September 1945, the Admiralty and the War Office handed back to the Harbour Board most of the harbour that they controlled from 1939 and on 30 November 1946, Dover ceased to be a naval base. Southern’s Lord Warden Hotel had been commandeered on 2 September 1940 as HMS Wasp, the headquarters of the Coastal Force Base and was returned to the Railway Company on 30 November 1946. Battered and badly scarred it was listed for a makeover and re-opening as a hotel. Southern, short of money and staff had other priorities. The building was repaired but not refurbished as a hotel, instead it was, and still is, used as offices.

Marine station was handed back to Southern and another plaque was added to the station’s war memorial stating, “And to the 626 men of the Southern Railway who gave their lives in the 1939-1945 war.” A considerable number of railway and seagoing personnel received awards for outstanding courage during and in the immediate aftermath of the war. Many came from Dover.

Once repairs and renovation had taken places, both of which were limited by lack of money and resources, Marine Station came into operation in April 1946. Later renamed Dover Western Docks, services to the station discontinued after 24 September 1994 and it was subsequently refurbished as a cruise terminal. The building is Grade II listed.

The official restoration of civilian services was inaugurated by the Golden Arrow linking up with the Canterbury on 15 April 1946 and the service resumed. The first exclusive train was hauled by Bulleid’s Merchant Navy Class, Pacific locomotive Channel Packet. Eventually, British Railway’s standard Pacifics, Iron Duke and William Shakespeare took over until electrification was introduced in June 1961.

The Autocarrier resumed service on 15 May 1946, later transferred to the Folkestone – Calais route until she was withdrawn in 1954. On 15 October 1946, the refitted Invicta replaced the Canterbury and became the company’s flagship carrying the prestigious Golden Arrow service. The Canterbury worked the Folkestone-Boulogne service passage until 27 September 1964, when she was towed away to Antwerp to be scrapped. The Invicta made her last Golden Arrow sailing on 8 August 1972 and the last Golden Arrow train ran on 30 September that year.

Following the War, the gantries were removed from the sterns of the train ferries and the Twickenham returned to the French until withdrawn in 1972. The Hampton, was taken out of service in 1969, re-fitted on the Clyde and towed to Greece, where she operated for 2 years before being sold for scrap in 1973. The Shepperton was withdrawn from the train ferry service in August 1972 and was taken to the breakers yard in Bilbao. The last overnight sleeper train arrived in Dover on 1 November 1980 at 06.30hrs and the final train ferry passenger service was 27 September 1985. The Dover Train Ferry dock closed on 8 May 1987.

The Victoria, from 1945 to 1947, returned to Dover to bring troops back from the Continent. She then returned to the Isle of Man and worked the passage there until August 1956 when she was sold for breaking up. The Biarritz also returned to Dover as a troop transporter until 1947 when she was transferred to Harwich. She returned to Dover in 1949 and June the following year was towed from Wellington Dock to the Eastern Arm to be broken up. The Isle of Thanet reopened the Dover-Boulogne service in July 1947 but in May 1948 was transferred to Folkestone until September 1963. She too was then brought to Dover until towed away on 10 June 1964 to be broken up.

On 1 January 1948 Southern handed over their ships, hotels and some 1,780 locomotives to the newly formed Southern Region arm of the Nationalised British Railways. The old company continued to exist as a legal entity until 10 June 1949 when it went into voluntary liquidation.

Published:

- Dover Mercury: 31 January 2013 – 14 March 2013 (8 parts)

Further Information:

- National Railway Museum York: http://www.nrm.org.uk