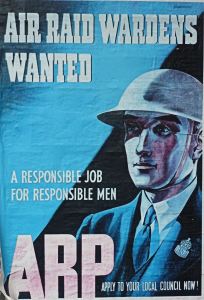

In the run up to World War II (1939-1945), the United Kingdom was preparing for the eventually of war. In 1938, air raid wardens were being recruited and households were given advice on how to build air-raid shelters in their gardens. War was declared on 3 September 1939 but it was not until 1940 that the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV) were set up. This was made up of men too young, too old or employed in vital civilian work to enable them to join the Armed Forces. Instead, these civilians took on the unpaid, part-time role of defending the country.

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports William Pitt as the Commanding Officer of the Cinque Ports Volunteer Fencibles c1805. Dover Museum

This was not the first time that local men in Dover had volunteered to defend the homeland. Back in 1775, in support of the American War of Independence (1775-1783), France declared war on Britain. As Dover was the nearest town and port to France, it was the most vulnerable and the Dover Volunteers were formed. These men were trained to fight the French should they invade and when troubles again appeared across the Channel in 1798, the Dover Volunteers were re-formed as the Cinque Ports Fencibles. This was by the decree of the Mayor, William Knocker and the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1792-1806) at that time, William Pitt (1759-1806), who signed up as a private. Dover’s contingency was part of a national movement that about 350,000 volunteers joined and William Pitt gained experience in every aspect of their duties and rose to become the commanding officer.

In Dover eight companies were formed, their main duties being that of observation and signalling. The latter meant that they were ‘stationed at different places along the coast to transmit to the others inland the news of the approach, if it should ever come, of the French fleet.’ At about the same time the Corps of Sea Fencibles for the Defence of the Coast of England against Invasion, was formed. Made up of seafaring men resident in Dover and other ports, their duties were to gain intelligence and to offer greater security to coast-trading vessels. With the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), the volunteers prepared to defend the South East corner of Kent including building fortifications as well as observing and signalling. However, in 1811, five years after William Pitt had died, the government voted to disband the volunteer militia and suggested that members should join the regular army. During the Wars the women of Dover made banners for the Dover Volunteers and these can still be seen hanging in the Stone Hall of Dover’s Maison Dieu. With rise of Napoleon III (1808-1873) in 1852, the volunteers were given an official blessing and reformed!

Inauguration of the Earl Beauchamp as Lord Warden 1914 – Market Square. Bob Hollingsbee Collection Dover Museum

The Boer War (1899-1902) gave rise to concerns that Dover was ill prepared in the event of European hostilities and a meeting was convened in the Town Hall under the Chairmanship of Mayor William Crundall. On 27 February 1900, the Dover Rifle Club was formed to help in the defence should invaders arrive. Initially, members practised in the Market Hall until, in 1903 the council provided a rifle range near Aycliffe. The East Kent Rifles evolved out of the Club and the mounted sectioned gained the Royal accolade. In 1914 when William Lygon 7th Earl Beauchamp (1872-1938) was installed as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, the riders of the Royal East Kent Mounted Rifles were part of the colourful procession. With the advent of World War I (1914-1918), the Volunteer Training Corps was set up, whereas members of brigades such as the Royal East Kent Mounted Rifles were encouraged to join the regular army.

With the preparations for war taking place before the outbreak of World War II volunteer organisations were officially set up including the Civil Defence Service in 1935. In 1941 a number of other services, such as the Air Raid Precautions (ARP), came under the Civil Defence umbrella, for instance, first aid and stretcher parties, the fire watcher service, gas decontamination teams, messengers, observers, rescue parties, wardens and welfare units assisted by the Women’s Voluntary Service. The uniform was dark blue battledress and berets with circular badges incorporating the letters ‘CD’ topped by the king’s crown and a larger one on the left pocket. However, although Germany was invading other countries at that time, little thought was given to the defence of Britain if it too was invaded.

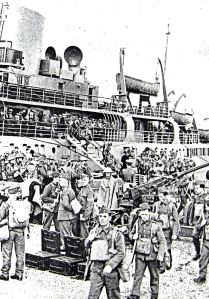

To keep the foe at bay, plans were drawn up for the transportation of men and materials to France and following the invasion of Poland, Britain declared War on Germany on Sunday 3 September 1939. The plans were immediately put into operation and the port and town was, as in World War I (1914-1918), declared Fortress Dover. This meant that all the restrictions applicable to a military fortress were put into place. Men of the British Expeditionary Force arrived and with guns, tanks and all the equipment and supplies necessary to maintain an army in the field were shipped across the Channel to Continental Europe.

In October 1939, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill (1874-1965), suggested the setting up of a volunteer Home Guard force. His idea was that the Force would be made up of men not eligible to be called up due to age or because they were in reserved occupations. Ideally, they would have the military background of taking part in World War I. Such organisations were already developing at the time, for instance the members of the Dover and District Rifle Club had formed themselves into an unofficial voluntary defence corps. Nothing more came of the suggestion due to the Munich Appeasement Agreement of 29 September 1938, when Germany, Britain, France and Italy agreed to the annexation of Sudetenland in Western Czechoslovakia. This, it was hoped would avert war.

However, in March 1939, Adolph Hitler (1889-1945) violated the Agreement and Nazi Germany firstly invaded Czechoslovakia. Their forces had employed blitzkrieg tactics, that is attacking with a dense force of parachuted-armed soldiers quickly followed by armoured, motorised infantry with close air support. Although each subsequent invaded country fought back, they were falling like dominoes and on 15 April 1940, at 11.00hrs the Netherlands Army signed their declaration of capitulation.

Later that day the British War Office announced their decision to create the Local Defence Volunteers as a last stance against the possible German invasion of Britain. On 3 May 1940 the Allied forces of Britain, the Commonwealth and countries already or under threat of invasion, were forced to pull out of Norway and on 10 May German forces were rapidly moving through France. In Britain an All Party Coalition was formed, headed by Winston Churchill, to rule the country. On 13 May the provisional outline for the Local Defence Volunteers had been drawn up.

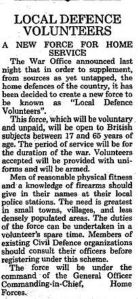

In the evening of 14 May, the new Secretary of State for War, Anthony Eden (1897-1977) made the radio broadcast announcing the formation of the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV), the purpose of which, he said, would be to guard against the possibility of German parachute troops landing. These troops, he went on to say, were specially trained and their function was to seize important points, such as aerodromes, power stations, villages, railway junctions and telephone exchanges. Their purpose was to disorganise and confuse as a preparation for the main body of troops. These, he said, he expected would come by both aircraft and by sea.

The War Minister then called for men who were British subjects between the ages of 17 and 65 to come forward to offer their services, on a part-time basis over and above their full-time work, for which they would not get paid, to help defend the country. Members of existing civil defence organisations, the Minister said, should see their commanding officers before volunteering. Further, men who would ultimately be called up under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act may join this new force temporarily but on receiving their calling up papers were to join the regular armed services. Mr Eden finished by saying that the volunteers should be fit, have a knowledge of firearms and would receive a uniform and arms. Those interested were to go to the local police station to sign on.

Almost immediately men started to arrive at Dover police station, but were told to come back at 08.00hrs the following morning. Over twenty volunteers were at the police station before 08.00hrs, where a specially manned table had been set up. Within an hour, a second table was set up and the call went out for more staff to come in and help out. Throughout the day men, mainly between the ages of 40 and 50 years signed up, the majority being World War I veterans. They included a General and several musketry instructors. Within the first twenty-four hours throughout the country some 250,000 men volunteered of which 600 had enrolled at Dover. The demand to join the local rifle club was unprecedented!

John Pratt, the 4th Marquess of Camden (1872-1943) as Lord Lieutenant of Kent (1905-1943) was made responsible for the Kent LDV’s and he sent telegrams explaining how they would operate. They were to function as units corresponding to police districts or in large organisations, within the work place, and be co-ordinated by a General Staff Officer with an hierarchy of area organisers, group organisers, company commanders, platoon commanders and section leaders. On 16 May, with the publication of the Defence (Local Defence Volunteers) Order in (Privy) Council, the LDV achieved official legal status. The following day, 17 May, the War Office by Statutory Rules and Orders 1940, No 748, stated that the LDV members would be subject to military law as a soldier. They then issued orders to the regular army on what had been decreed adding that the leaders of units would not hold commissions or have the power to command regular forces. The role of the LDV’s, in the case of invasion, was to try to slow down the advance of the enemy, even by only a few hours, in order to give the regular forces time to regroup.

That week the Commander-in-Chief of Home Forces (1940), General Sir Edmund Ironside (1880-1959), requested owners of rifles who were willing to lend them to the LDV’s to notify the police station nearest their homes, giving details of type and any ammunition held. This was followed by instructions from the Home Secretary (1940-1945) Herbert Morrison (1888-1965) for the police to take possession of stocks and firearms in gunsmiths’ shops, and an Order issued prohibiting aliens (foreign nationals) from possessing firearms without permission from the police.

On 18 May Captain William (Bill) Moore was appointed to command the Dover Company of the 8th (Cinque Ports) Battalion of the Local Defence Volunteers and on the 22 May, five platoons were formed and prospective officers appointed. However, not having any premises, for the first year Dover’s LDVs headquarters were vacant rooms separately located in premises along the Seafront. A couple of boxes of uniforms did arrive – one contained linen overalls and the other field service caps. This lack of the promised uniforms was reflected elsewhere and so an official announcement was made that those without uniforms were to wear armbands with the letters L.D.V embroidered on them.

Dunkirk Evacuation 27 May – 3 June 1940, line of evacuees making their way to a waiting ship. Doyle Collection

By this time the German forces were rapidly approaching Amiens, northern France, and by 21 May advance attachments had reached Aisne. Although putting up desperate resistance, thousands of Allied troops, mainly comprising of the British Expeditionary Force, were being cornered at the port of Dunkirk. Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945), who had served with the Dover Patrol in World War I, was in command of Fortress Dover and also in charge of the Evacuation of Dunkirk. On Sunday 26 May Operation Dynamo was put into action when under Ramsay’s direction. A fleet of 222 British naval vessels and 665 other craft, known later as the Little Ships, went to the rescue of the beleaguered troops. The Dunkirk Evacuation continued over the following nine days when 180,982 men were landed at Dover and some 327 trains took the survivors to locations throughout the country.

The collapse of all Continental resistance gave the Nazi’s complete command of Europe’s western seaboard from Narvik in the north to the Spanish frontier in the south. This provided air and naval bases that made Britain within easy range for invasion.

Road Block on Folkestone Road at Farthingloe. Dover Museum

On the evening that Operation Dynamo was put into action, Captain Moore and the LDV volunteers went out on night-duty patrols over the hills and cliffs surrounding Dover. The LDVs main duty was to work in close collaboration with the local stations of the Observer Corps by watching out for and to report enemy landings. Also, to prevent movement by blocking roads and patrolling and protecting vulnerable locations. However, in order to avoid mistakes and confusion, all men were to act on the instructions of their commanding officer, who in turn had to act in accordance with his section commander. In the event of invasion, they were to deal with the enemy paratrooper parties as they landed and this led to the LDV’s being given the nickname parashootists. A bit of a misnomer as most of the LVDs were armed with home produced weapons such as pikes made of well-sharpened kitchen knives attached to staves. Anger was vented against the 1937 Firearms Act, which had removed from private hands the now much needed weapons and those earlier weapons had subsequently been destroyed.

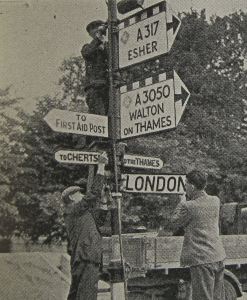

On 4 June Churchill made one of his many resounding speeches, on this occasion to Parliament and opened with, We shall defend our island whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the landing grounds, in the fields, in the street and in the hills... Apparently, afterwards, Churchill said to a colleague, and we will fight them with the butt end of broken beer bottles because that’s all we bloody well have got! A Defence Area consisting of the coastline and twenty miles inland from the Wash in Lincolnshire to Sussex was put into force. Within this Defence Area movement was restricted and passes were essential The manning of checkpoints was mainly undertaken by the LDV. They were also ordered to remove all place name signs within the Defence Area and to help with camouflage, under the directions of professionals from film studios and theatres such as Glyndebourne.

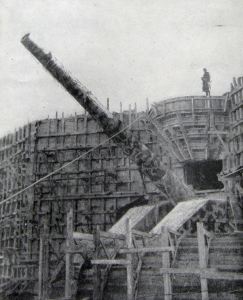

Winnie or Pooh 14-inch ex-naval gun capable of firing their missiles across the 21-mile wide Dover Strait to France. Dover Museum

The LDV also helped the military to erect a continual barbed wire barricade along the coast with a battery of guns covering every likely line of approach. They built sentry boxes by the checkpoints and watched all approaches to cities, towns and villages. They built pillboxes, dug trenches and prepared to take on the enemy at close quarters if necessary. Around Dover and the harbour, all batteries were manned 24/7 and local railway lines were utilised as mobile batteries. Behind the cliffs of St Margaret’s Bay the first big artillery batteries were being prepared and within a month Winnie and Pooh, two 14-inch ex-naval guns capable of firing their missiles across the 21-mile wide Dover Strait to France, were installed. On 2 June 1940 the evacuation of 2,899 school children to Monmouthshire in Wales began. They left from Dover Priory railway station with teachers and helpers.

It was again announced that the LDV would be issued with uniforms and that the dark blue berets worn by the Royal Army Service Corps were about to the despatched. Although some 90,000 khaki coloured cotton twill overalls consisting of an army style blouse and trousers were about to be despatched, re-equipping men returning from Dunkirk took precedence, so only a few arrived. In the meantime, the LDV men made do with their own practical clothing and members of the local WVS were asked to make armlets, more correctly called brassards, out of whatever khaki coloured material was available and to embroider LDV on them until special ones were manufactured. In all, there were at that time, some 1,500,000 LDVs but eventually uniforms along with some arms, ammunition and bombs arrived at battalion HQs at all times of day and night and in Dover at the LDVs different locations!

America, at this time, was following a policy of isolation and their Neutrality Act forbid any involvement in what was happening in Europe. Albeit, the American Committee for the Defense of British Homes had been set up following the introduction of the 1937 Firearms Act in Britain. One of the leading members was industrialist and businessman Richards W Cotton. Shortly after War was declared, although the Neutrality Act forbid any involvement on either side, nonetheless, he set up a counterpart organisation in Britain. The role of this organisation was to receive and distribute gifts sent by the American fraternity. These gifts were arms, ammunition and money for equipment and on arrival in Britain were distributed to the LDVs. Of interest the guns often had tags attached asking for them to be returned to the owner after the war was over! It was estimated that prior to the US entering the War in December 1941, Cotton’s organisation had sent 1million World War I rifles and 1,000 privately owned field guns plus the appropriate ammunition!

Local Defence Volunteers – Training included learning how to make ‘Molotov Cocktails’ to throw under enemy tanks. Doyle Collection

Training of the LDVs was held at weekends when, except for shift workers, most could attend. The sessions were organised with the co-operation of the National Rifle Association and with the help of regular soldiers. It was assumed that all the volunteers had firearms experience but before going out into the range, instruction was given on the different parts of the rifle and about the use of fixed apertures or battle sights, as they were called. Once on the range, the shooting was at 200 yards and the volunteers were allocated targets and told to aim about a foot below the bulls eye. About 1,000 volunteers were trained each weekend that summer and given instruction in unarmed combat, making and throwing Molotov Cocktails to deal with enemy tanks – bottles partially filled with a mixture of petrol, paraffin and crude oil – and given instruction on discipline, observation, judging and recalling distances. The LDVs were instructed on making verbal and written reports of what they did and any occurrences when they were on duty.

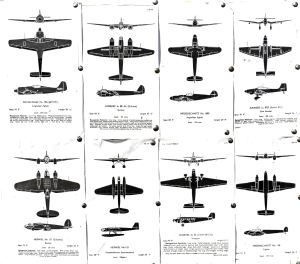

By the end of June, Northern France was in German hands leaving Britain open to attack. The roles of the LDVs by now had developed into the needs of the locality they served and the scale of the attack likely to be encountered. In the Dover area, some of the LDVs had almost the static job of manning positions, roadblocks and vulnerable points in order to slow down the enemies advance, should they land. Others were responsible for the manning of searchlights and undertaking patrols either on foot, bicycle or horseback. Should invasion occur, this section were to be a mobile reserve, acting and striking quickly. At 05.20 hours on 6 July the first enemy bomb fell on Dover and 10 July saw the start of the Battle of Britain – the prolonged aerial conflict for the control of the skies above the Channel and South Eastern England. This was between the Luftwaffe (the German Air Force) and the Royal Air Force. The Battle was to last until 31 October 1940.

The Battle for Britain was the first phase of the German Operation Sea Lion, a three phased planned invasion commanded by Reischsmarshall Hermann Goering (1893-1946) the top ranking soldier of all Germany, and Grand Admiral Eriche Raeder (1876-1960) who was in charge of the German Navy. This first phase was envisaged to be the aerial bombardment of Britain’s coastal defences. This was to be followed by an elite unit, called the Wild Dogs, who would wear British Army uniforms. They were to be parachuted in and hold key positions until the main body of troops arrived. These were to be nine divisions of 67,000 men who would be towed across the Channel in barges. The barges were already in place at the Continental Channel ports. During the crossing and throughout that invasion, the main force was to be supported by an airborne division.

The main attack was to be on Dover but at the same time, to cause confusion and split the defences, there would be an attack on Brighton. At Dover, the Wild Dogs would have been expected to have seized the harbour, railway stations and the cliffs by the time the main force arrived. The German Forces would then take London and impose the New Order. Resistance was expected and therefore all men between the ages of 17 and 45, with the exception of those belonging to the vital professions, were to be deported to Continental camps.

Home Guard outside the Royal Oak, Capel-le-Ferne c1940 . Note the greatcoats and steel helmets, possibly borrowed for the photograph. Dover Museum

At the instigation of Churchill, on 22 July the LDV were renamed the Home Guard. The administration was put on a firm footing by being given to the Territorial Army Associations and Auxiliary Air Force. Home Guard battalions of over 800 men were to have an administrative assistant, specially released from the regular forces, for the efficient functioning of the battalions. In Dover, most of the Home Guards had uniforms but that was more due to distribution logistics than to needs. Dover was a town with railway stations and frequent trains! In many rural areas and relatively isolated towns, the situation was entirely different. It was even worse where battalions were scattered over a number of villages each with their own company. Most battalion commanders had to find their own transport and large boxes were not easy to distribute especially with wartime petrol restrictions. By the end of August, blankets started to arrive in Dover that were to be used until great coats were ready. In fact, due to shortages of materials and other demands, the notion of providing greatcoats changed to that of capes made out of heavy serge. The men were also issued with simple canvas bags for carrying arms and ammunition.

Although asked for, steel helmets were slow to arrive, so make do and improvise created various forms of head protection. Training in towns tended to be in Drill Halls where many, like in Dover, had its own miniature firing range. However, in Dover, the Drill Hall, near Mote Bulwark, was being used by the military so it was not available for use by the Home Guard. They like their counterparts in the country battalions had to make do with whatever facilities were available. However, they were better off than the Home Guard Volunteers living outside of the town in one respect were. The country Home Guard had to cycle maybe three to five miles to the training facility and then back again all after a hard day’s work. In Dover, at least the facility was not far away but the Home Guard faced a bigger and more dangerous problem – the constant attacks that made any journey in the town precarious. Towards the end of July, on one of his many visits to Dover, Churchill suggested that the Home Guard’s night-duty patrols on the hills and cliffs were to be transferred to the Seafront.

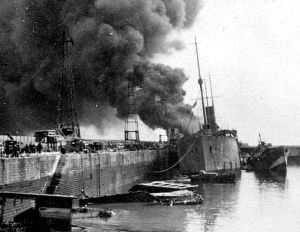

Every night for the rest of the War, without official waterproofs but with steel helmets and Lee-Enfield rifles, the Dover Home Guard patrolled Dover’s Seafront – England’s front line to the enemy held Continent. Very quickly, these Home Guards were also asked to help within the gun batteries, of which there were many on the Seafront and on 29 July they had their first taste of direct action against the enemy. Since capturing northern France, the German firepower was aimed at Channel shipping. That morning, Junker 87s dive-bombers attacked the harbour. Initially there was a single reconnaissance aircraft that was speedily driven off but shortly after, flying out of the sun came the Junkers escorted by some 50 Messerschmitts.

As they approached the harbour the Junkers formed groups of eight and in almost vertical dives they attacked. The Naval Auxiliary ship Gulzar and other vessels in the Camber, Eastern Dockyard, were wrecked and the Codrington nearby was hit, setting on fire the 10,000-ton naval supply ship Sandhurst which was full of torpedoes, ammunition and fuel oil. Dover’s firemen fought the blazes for many hours and they were justly awarded the George Medal and King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct. It was reported that the high rate of gunfire took their toll on the German planes and although the Home Guard did not officially come on duty until late that day, those that were during and immediately after the attack, were congratulated on the part they played.

German pilot Artur Dau shot down 28.08.1940 over Hougham being interviewed by PC Hills, with left to right Home Guard, Jack Wood, ARP Warden Cyril Souton and local Mr Worrall. Kath & Bob Hollingsbee Collection

On 12 August shelling started from the big guns erected on the cliffs of France and a man and a woman in Dover were killed. Following this attack, shelling became a frequent occurrence, coming out of nowhere and causing instant death or injury – a special shelling siren was introduced in October. On 28 August, Squadron Leader Peter Townsend (1914-1995) had shot down the plane that Hauptmann Artur Dau was piloting. Dau bailed out, landed near Hougham and quick on the scene were Jack Wood of the Home Guard, Police Constable C Hills, Cyril Souton of the ARP, a Mr Worrall and a camera man. The photograph taken that day shows the German pilot being taken into custody by PC Hills with the others looking on. Of note, Cyril Souton, a bus driver with East Kent Road Car Company, became a Parish Councillor and died in 1981 in his 80s.

In September formal training of the Home Guard was started with residential courses for officers and local courses for the rest. The courses provided military defence training, including the manning of batteries. Those on Dover’s Seafront were, by this time, being manned at night by the Home Guard in order to release some regular soldiers so they could return to the Front. The number of checkpoints in the South-East corner of Britain continued to increase and for the same reason, were taken over for the Home Guard to man. Pedestrians, cyclists and motorists were stopped at every post and had to produce the relevant passes. The closer they approached Fortress Dover, the more frequent the checkpoints. On one occasion a motorist refused to stop on the Dover-Deal Road (A258) checkpoint near the turn off for St Margaret’s, and was shot.

On Saturday 7 September General Headquarters to Home Forces broadcast the code word Cromwell at 20.00hours . This signified that the German invasion was imminent. In Dover that day, folk had watched what seemed like a thousand German aircraft, made up of bombers and fighters, overhead. The objective of the planes was to blitz London. The Home Guard in Dover was out in force that evening when the code word was issued. On the Seafront they were at the ready. However, excepting for a lone Heinkel 11 heading back to base, they did not see anything untoward. The Heinkel was shot at and it dropped its load into the harbour but did little damage.

During the summer of 1940, the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, General Ironside, advocated a special line of defences to delay the enemy if invasion took place. To use his words, it was to ‘prevent the enemy from running riot and tearing the guts out of the country as has happened in France.’ Colonel Colin McVean Gubbins (1896-1976) was appointed commander of these special units and the task of setting them up was given to Captain Peter Fleming (1907-1971) – the elder brother of Ian Fleming (1908-1964), author of the James Bond stories. Known as the 201 Battalion of the Home Guard it was formed in the late autumn of 1940 from volunteers within the Home Guard who met certain requirements. They had to be willing, able to keep secrets and have knowledge of every nuance and crag in their locality. Royal Engineers were given the task of building underground bunkers located in areas suggested by the new recruits, ideally in woodland with an entrance that could be well hidden.

One special unit was at Drellingore, not far from Bushy Ruff, in the Alkham Valley. Local military historian, Roy Humphries, described the underground bunker as having an entrance covered by a hinged large old tree stump. Underneath was a concrete lined vertical shaft about three feet square and eight feet deep with iron climbing rungs let into the side. At the bottom of the shaft was a large chamber approximately 16-feet square with a small tunnel at the furthest end and known as the bolt hole. The main chamber was roofed with corrugated iron sheeting and had a wooden floor. In it were two three-tier wooden bed-frames, a trestle table, locker, chairs, a 50gallon galvanised-iron water tank, an Elsan toilet, enough rations to last the occupants three weeks and a small keg of rum.

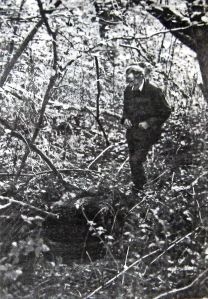

Drellingore Top Secret camp with one of the special Home Guards, Sam Osbourne looking at the entrance. Dover Express War Supplement 01.09.1989

The Drellingore platoon under the command of Lieutenant Cecil Lines and his team, nicknamed the scallywags, consisted of Sergeant George Marsh, Samuel Osborne, Thomas Holmans, Charles Fayers and Dennis Dewar. The armaments supplied to the platoon included rubber truncheons, a Thomson Sub Machine Gun, two Springfield .300 rifles, two bayonets, grenades, phosphorus bombs, paraffin incendiaries, delayed pencil fuses, detonators, gelignite, sticky bombs, mines, spools of trip wire and plastic explosive. Each man was personally issued with a .38 Smith & Wesson revolver, a Fairbairn Commando knife, a brass knuckleduster and a pair of rubber plimsolls.

The men underwent regular training sessions at Tappington Hall, Denton in the Elham Valley, where they were taught the best way to destroy vital emplacements without the enemy realising it was sabotage and with particular emphasis on the destruction of fuel and ammunition dumps. The men also became experts in unarmed combat and were taught to kill silently. However, they were made aware that because of the nature of the job, if captured the six men would be considered to be outside the rules of the Geneva Convention so could be shot as spies.

Because of the secrecy involved, there are very few details as to how many and the location of these secret units but it was believed that there was one at Wanston Farm, St Margaret’s. This was close to the Battery complex that was constructed in 1941, which housed two 15-inch guns, nicknamed Jane and Clem. On the Romney Marsh, four special platoons were established, one of which was at Snargate, where the special chamber still exists and is registered as an ancient monument. The special units were phased out during 1943 but as D-Day of June 1944, approached there was a move to parachute these specially trained men into France to help the resistance Forces but the idea was dropped.

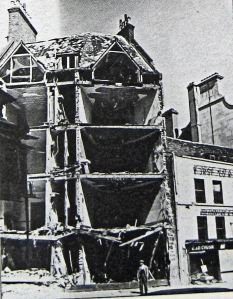

Wellesley Road looking towards Townwall Street attacked on the same day that Home Guard Fred Hayward was killed. Dover Library

Gas fitter Fred Hayward was the first Home Guard to be killed by enemy action in Dover. On Wednesday 11 September, from just after 15.00hrs in the afternoon until nearly midnight Dover was subjected to both bomb and shell attacks. One of the bombs fell near the entrance to Priory Station goods yard off the Folkestone Road, causing a large crater and cutting gas, water and electricity mains, which was an emergency. Once the water supply was cut off, dealing with the multi-fractured gas pipe became the priority but because of the mess in the crater this was proving difficult. Several hours had gone by and at 23.15hours, with shells being fired overhead, Fred was trying to seal the fractured pipe and was beginning to feel that his job was almost done. Nearby the bomb-disposal officers were still trying to disarm the bomb when it exploded.

Fred, a married family man who lived at 52 Tower Hill was killed. Even though he was not on duty as a Home Guard, Fred was buried with full Home Guard honours in Charlton Cemetery. By this time serious consideration was being given by the government, to the local Civil Defence personnel being trained as a special local Home Guard battalion. Undertaking their volunteer duties within the Civil Defence, as normal but if invasion was imminent, they were to take up arms as part of the Home Guard.

Norman Sutton one of the Home Guard who manned Dover’s Seafront during World War II and also provided the national newspapers accounts of weather over Dover. Terry Sutton

On 12 October, Hitler postponed the Operation Sea Lion invasion to the spring of 1941. This was, of course, unknown at the time especially as the bombing and shelling of Dover remained unremitting. The Home Guard kept up their nightly vigil on the Seafront and from there they could see the anti-aircraft gun (ack-ack) flashes over Calais. When asked about this, one Home Guard was reported as saying, ‘We’re giving Jerry a taste of his own medicine.’ An upbeat answer to what was being seen by the War Cabinet as ‘suicide duty’ by Dover’s Home Guard on the Seafront. At the time Home Guard, Norman Sutton (1914-1986) was one of those whose duties were on the Seafront and he was also a reporter with the Dover Express (later the Editor). Reporting restrictions had been imposed within Fortress Dover with the outbreak of War but in 1940 they were lifted. From then on, Norman Sutton’s weather reports from Dover were published on the front page of most national newspapers and became famous!

Philip Henry Kerr, the 11th Marquess of Lothian (1882-1940) was the British Ambassador to the United States and in November 1940 he came to Dover, ‘to see what Hell’s Corner was really like.’ During his visit the Ambassador saw the bomb damaged Dover Police station – where the first volunteers for Dover’s Home Guard signed on. He then met members of the Home Guard manning Dover’s Seafront and it was planned that his report to the US Government would be aimed at gaining economic support for Britain from the US. Albeit, on arrival in New York on 23 November journalists there reported that he told them that ‘Britain was broke, it’s your money we want,’ this had the negative effect of being exploited by German propaganda. A Christian Scientist, Lord Lothian died on 12 December 1940 having refused medical treatment.

At the end of 1940, Captain Moore, the Commanding Officer of the Dover Company of the Home Guard, left the town and Major M G Logan took his place. By this time employers platoons in the town included the Post Office, Southern Railway, Dover Harbour Board, East Kent Bus Company and the municipal Gas and Electricity works. The main task of the members of these Home Guard units was the defence of their employers’ premises. During the first few months of 1941, the Germans were concentrating their efforts on night bombings and so the Dover Company was on full alert. However, as London, industrial areas and ports further to the west and north east of the country were the main targets, the town and port of Dover was left relatively free from attack.

Flashman’s Depositary, Dieu Stone Lane shelled 31 March 1941. Kent Messenger Group

There were the occasional tipper and jettison raids, the latter applied to the enemy aircraft that jettisoned their remaining bombs before returning to the Continent. In March that year, five jettisoned bombs were dropped near Granville Gardens totally demolishing one of the Home Guards gun sites but there were no casualties. By the end of that spring, the situation hotted up again with the Junker dive-bombers causing deaths and injuries. Further, in the first six months of the year the town was heavily shelled on 15 separate occasions adding to the mounting injuries and loss of life and property.

Although, the Dover contingency of the Home Guard were well armed and had been issued with respirators and tin hats, in other parts of the country the Guardsmen were relying on home made weapons and no protective clothes. In June 1941, Churchill put pressure on the War Office to do something about this and in response 250,000 pikes, made out of steel tubing with a welded bayonet on the end, were issued! This caused uproar with questions being asked in Parliament, to which Baron Henry Page Croft (1881-1947), the Under Secretary of State for War (1940-1945) responded, saying that ‘a pike was the most effective and silent weapon!’ It seemed evident to many that the Under Secretary had little respect for the Home Guard and general moral went down.

Eventually, Sten Sub-Machine Guns were issued to the Home Guard but some units had to wait until 1943 before receiving them. To increase moral, administrative assistants were superseded by adjutant-quartermasters during 1941 and a permanent staff instructor was allocated to each Home Guard battalion. However, the call-up of men to join the regular forces was taking its toll on numbers, particularly in specialist fields. This meant that existing members were expected to take on the mantel of these specialist skills as well as their own and train new recruits. Further, as Home Guards, on reaching the age of retirement – 65-years, were expected to leave this was having an adverse effect. At local levels, where the men were fit and keen to stay on, they did but gave up any rank they previously held.

The number of German pilots forced to bail out of their burning planes steadily increased and one such badly injured pilot landed in a Hougham field. He was met by Home Guard Percy Atkins and his colleagues who released the pilot from his parachute and carried him to the nearby farmhouse. There, first aid was administered by the Civil Defence volunteer and following the pilot’s arrest, the local police took him to hospital. At St Margaret’s the Home Guard were quickly on the scene when another injured pilot, Hauptman Pingle, carefully landed his disabled plane. Pingle was arrested and taken to hospital but on examination of the plane it was found to be a new Me 100f. Experts were soon on the scene and announced that it was sufficiently intact for examination. It was carefully loaded onto a lorry and taken away.

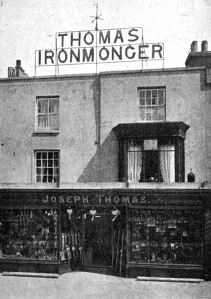

Thomas’ Ironmongers 84-86 London Road for a while the HQ of the Dover Home Guard during World War II. Dover Museum

Around the first anniversary of the forming of the Dover Home Guard, their headquarters in rooms on the now battered Seafront, moved. This was to Thomas’s ironmongers’ store 84-86 London Road and the previous March, Major Logan was succeeded by Major F A Belchamber as the Commanding Officer. The main brief of the Home Guard at this time, besides controlling roadblocks, was the ‘waiting and watching’ while manning of the night time defences on the Seafront. A reporter writing in the 27 August 1941 edition of the Times described the coastal batteries in and around Dover as well-hidden strong points. He went on to give an account of looking through powerful field glasses from one of the Home Guard’s observation posts towards Calais. He said that he could make out one of the long range gun emplacements and was told that the number of such batteries were constantly being increased. With them, the number of attacks on shipping in the Channel and the town also increased.

Burlington Hotel following an attack by a Junkers dive-bomber 7 September 1941. Dover Library

On the evening of Thursday 2 October 1941 Home Guard William Stacey, aged 66, after doing his stint, was walking to his home at 10 Rope Walk when three Heinkel flew over the western side of the town. Dropping part of their load, these exploded along Limekiln Street and on Archcliffe Road demolishing a row of houses and two pubs. William Stacey was killed instantly. Buried in St Mary’s cemetery his coffin was covered with the Union Flag and his Home Guard colleagues attended.

Royal Engineer Army Officer, Lieutenant Alfred John Whittingstall from Jarrow was giving hand grenade instruction to the men of the Capel-Le-Ferne platoon B Company 8th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, when one of the Home Guards dropped a live grenade. The Lieutenant ordered the men to lie down and he threw himself, with his feet pointing at the grenade to limit the danger area. It exploded and Lt.Whittingstall was injured. For his bravery the Lieutenant was awarded the MBE on the recommendation of Lt General Bernard Montgomery, Commander-in-Chief, South East Command but a year later Lt Whittingstall was killed on active service in Egypt. It was about this time that it came to light that due to the lack of facilities some Home Guard commanders were keeping grenades and other lethal explosives under their beds and equally unlikely places at home! The Royal Engineers were drafted in to help the Home Guard build ammunition storehouses, which then became compulsory for the storage of such weapons.

On Thursday 18 December 1941, Captain Henry Margessen (1890-1965), the Secretary of State for War (1940-1942), proposed the compulsory enlistment for the Home Guard with a maximum of 48-hours duty in any four-week period. Built into the proposal was a certain amount of flexibility to take into account the demands on members’ full-time jobs, for instance, farm labourers during harvest time. It was also proposed that the age of joining would be reduced to 16-years but that the youngsters would be limited in the duties they were expected to undertake. The compulsory enlistment of men to the Home Guard was confirmed by the National Service Act of 1942, with the added clause that those who failed to attend practices, parades or turn up for rostered duty were likely to be prosecuted. In September 1944 David Davies, a 20-year-old miner at Snowdown Colliery was fined £8 9shillings 6pence at Dover Police Court for not attending a Home Guard parade. Consideration was also being given to women joining the Home Guard and in December 1941 the Women’s Home Defence was formed. Headed by politician and writer Edith Summerskill (1901-1980) the women were given basic military training and undertook duties within platoons.

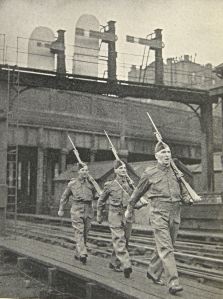

Royal Army Service Corps and members of the Home Guard searching the vegetation along a Southern English beach for enemy paratroops – government leaflet. Doyle Collection

To release more men for front line duties, the Home Guards’ duties were extended to include the general manning of coastal artillery guns and at Dover this meant day operations as well as at night. In 1942 Home Guards being used to defend airfields operated by the Royal Air Force, on the premise they knew their locality better than the regular troops, were learning how to shoot paratroopers while they were descending. Home Guard transport units were set up to relieve regular Royal Army Service Corps drivers and these units of the Home Guard were given the authority to impress vehicles for military use on action stations. 48hundred-weight vehicles were provided for country battalions and motor cycles were issued for despatch riders. Having come a long way in training and equipment since June 1940, military authorities had be constantly reminded that the Home Guard was still a part-time force made up of men with full time jobs as civilians that, nevertheless, could find themselves facing highly trained German troops.

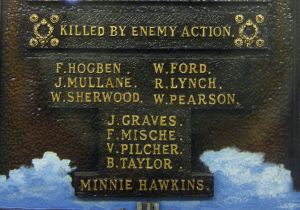

The East Kent Bus Company had its own Home Guard of which William George Ford, Robert Magnus Lynch, Frederick Mische, Victor William Pilcher, Walter Sidney Sherwood and Brian Taylor were all members, indeed, Brian Taylor was a lieutenant. The garage in Dover was in St James Street and on the evening of 23 March 1942, they were finishing for the day when, at 19.15hours they heard the sirens. In the Market Square, the East Kent Bus Office was hit killing members of staff and at the bus garage all but local manager, Brian Taylor who wanted to finish something, ran to the shelter in the basement. Bus conductress, Minnie Hawkins, didn’t quite make it when the German Junker’s JU88 dropped its the armour-piercing bomb that penetrated the roof of the garage and the shelter below.

The Civil Defence, soldiers and locals were quick on the scene. On clearing the rubble they found Brian Taylor, aged 32 and of Rose Cottage, Kearsney, who was killed in his badly damaged office. Minnie Hawkins was killed just outside the shelter but the shelter itself was filling up with water from a burst main. The rescue squad managed to get into the shelter through a hole in the roof by the time doctors and nurses arrived and a shuttle service of ambulances was arranged to take victims to hospital. Bus Inspector William Pearson was one of the first hauled through the hole. He was followed by William Ford, aged 29, Frederick Hogben, Robert Lynch, aged 37 of Elms Vale Road, Frederick Mische, age 45 of Winchelsea Street, was an ARP Ambulance driver as well as being a member of the Home Guard and bus driver, Walter Sherwood age 31 of Underdown Road. They were all dead. Victor Pilcher aged 26 was found still alive but died four days later at the Casualty Hospital, now Buckland Hospital, from internal injuries. Members of the Home Guard were bearers of their colleagues’ coffins and representatives of the Transport and General Workers’ Union attended. The bus company’s office was moved to Lydden. A memorial and special display can be seen at the Dover Transport Museum, Whitfield.

Drill Hall Townwall Street 1912 badly damaged in World War II but after repairs were undertaken, in October 1942 it became the HQ of Dover Home Guard. Dover Museum

The second anniversary of the forming of the Home Guard was marked by King George VI (1936-1952) becoming the Colonel-in-Chief. To reinforce the national importance of the organisation, the training branch was transferred from a Directorate to the General Head Quarters Home Forces. The term volunteer ceased and all ranks in the Home Guard matched regular army usage. In addition regular army officers were appointed to every three battalions for training purposes and a car was provided for the adjutant. He was also given the regular services of an army quartermaster to relieve him of some of his administrative work. Major Belchamber was obliged to resign as Commanding officer of the Dover Brigade in September 1942, as he was over 65years old and was succeeded by Major PA Mills. The following month, the Company moved to the repaired, badly damaged, Drill Hall in Liverpool Street, which had its own miniature firing range.

A few weeks before the anniversary, a 17-year-old Home Guard private was picked up trying to get onto the heavily guarded Dover beach. In his statement to the police, he said that he had come from Suffolk with the intention of killing Pierre Laval (1883-1945) a French politician and Jean Louis Darlan (1881-1942) a French Admiral and politician. Both men were serving in the pro-German French Vichy regime. The young Home Guard saw both politicians as traitors who should be dealt with. He also planned to shoot a few Germans and do some serious destruction en-route. When arrested he had with him a Thompson sub-machine gun (tommy gun) and ammunition and told the court that he took the gun, as he knew that a rifle would be no good. He went on to say that he had never fired a tommy gun but that he had read the instructions! The magistrates fined him £2.8shilling and put him parole for stealing the gun and ammunition. Of note, a young Frenchman assassinated Darlan on 24 December 1942 and Laval was tried for High Treason and executed by firing squad following the end of the War.

On the evening of Saturday 6 September 1942, some hundred shells were fired at Dover and an armour piecing type hit Pioneer Road damaging nearby properties. On Home Guard duty was farm worker, Lance-Corporal Leonard White age 37, who was seriously injured and died later in hospital. Loud speakers came into operation on Dover streets in early October 1942, to warn people of imminent danger and on 23 October, the battered but still functioning Priory Station was the scene of lasting historical interest. Field Marshall Jann Christian Smuts (1870-1950) the Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa (1939-1948) visited the town accompanied by regular visitor, Prime Minister Winston Churchill. They inspected some 130 representatives of the Civil Defence Services and members of the Home Guard. Shelling was almost a daily occurrence and on the evening of Thursday 10 December one of the many shells was an airburst type. This exploded over Priory Station and another shell hit 79 Folkestone Road where Home Guard, Company Sergeant Major David Burns, was killed.

Although the destruction and devastation of Dover continued, at the end of 1942, William Boulton Smith, the Borough Engineer since 1920 put forward a plan for the reconstruction of Dover in the event of peace. The plan covered a period of fifty years and was adopted by the council at that time but it was not until the late 1940s that the plan, with adjustments made by Town Planner, Professor Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957), was put into action. This was the basis of what we see today. In the meantime, the War carried on and the destruction and casualties mounted. In February 1943 the former manager of Dover’s Lloyds Bank, Ernest Lyford, who had retired to Surrey, was accidentally killed by a bomb at a Home Guard practice. In March there were reports of mysterious explosions coming from the French coast that led to speculation that a new type of weapon was being introduced. Fear quickly mounted that it would be tried out on Dover.

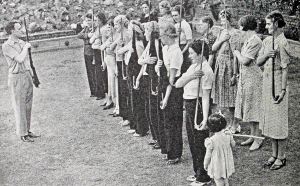

On 16 May 1943 the local Home Guard celebrated its third anniversary by staging a display at Crabble Athletic Ground and Home Guard battalions in the surrounding villages also held celebrations that day. A formal parade took place in London, with the King accompanied by Sir James Grigg (1890-1964) Secretary State for War (1942-1945) and General Sir Bernard Paget (1887-1961) Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces (1941-1944) taking the salute. The parade was made up of officers and other ranks from every Home Guard battalion in London and there were representatives from every area and from the specialist groups. They all wore battle dress, steel helmets and respirators. In the evening there was a special service at Westminster Abbey.

In the US, Churchill gave a speech at the White House in praise of the British Home Guard, which was broadcast in Britain. He said that there were 2million Home Guards and spoke of their faithful unwavering and indispensable work from the darkest days of the summer of 1940. When Britain stood alone, he said, and the Home Guard relied on improvised weapons and wearing armbands. The Prime Minister went on to say that the Home Guard, each had uniforms, were well trained and were equipped with arms and ammunition. There were also women Home Guards who handled guns, were involved in manning coastal batteries and drove and maintained motor transport. Further, Churchill reminded his audience, they all had daily work in fields or factories and that their work in the Home Guard was gratis.

Post Office, Priory Street, shelled on 28 June 1943 killing Walter Garrett, George Kerry and John Parfitt. Kent Messenger.

The night of 28 June 1943 saw a German convoy of three merchantmen with an escort of E-boats traversing the Dover Strait on which British gunners opened fire. The Germans on the French coast retaliated and many shells hit Dover. One large shell hit the General Post Office in Biggin Street/Priory Street on the Priory Street side, killing Walter Garrett, George Kerry and John Parfitt. George Kerry and John Parfitt were members of the Home Guard and at their burial their coffins were covered with the Union Flag and borne to their graves by their colleagues in the Home Guard. On that night, while helping at the incident, ambulance driver William Golding was killed. Due to the damage, the town was without telephones for three weeks except for emergency calls.

This retaliatory action of the Germans of firing on the town was a deliberate ploy in the hope that locals would complain about the British long-range guns attacking the enemy’s shipping passing through the Strait of Dover. Dovorians, however, were stoical and were more concerned about their children who were drifting back from evacuation in Wales. As the weather had been kind to farmers producing one of the biggest crops in years, many mothers took their offspring to the surrounding countryside to help get the harvest in and keep them out of harms way. Members of the Home Guard, also planned to help out on the farms but orders came that they were to help troops in the area to widen lanes, erect telegraph poles and build more gun emplacements. Before the end of August 1943, truck loads of food, fuel and armaments arrived in the town, which the Home Guard helped to unload. When they had the time, they were undergoing further military training.

At the beginning of September, Operation Sankey was put into effect. This was an amphibious exercise involving hundreds of men going through embarkation routines and partial crossings of the Channel on various types of craft. Overhead, the seagoing craft were protected by waves of Royal Air Force and Unites States Air Force planes. On land, the Home Guard manned the increased number of checkpoints and gun emplacements that they had erected. Others, along with military personnel, were marching, in full uniform and carrying weapons at the ready along the cliffs and around the country lanes or manning the newly erected gun emplacements.

The spring of 1943 had seen the successful ending of the Siege of Stalingrad (1942-1943) and at El Alamein, North Africa (October-November 1942) the German advance had been checked. In Britain, months of planning and careful preparation were taking place and this began to take shape on 10 July when the Allies landed in Sicily. This was the start of a continual offensive that would liberate country after country until the Allied armies reached Germany and was noted for the remarkable degree of co-operation. Operation Sankey was part of this offensive and what was one of the biggest, longest running and dangerous charades of the War – that of deceiving the German’s into believing that the invasion would come from the south-east of England. The operation was a continuing success for in speeches the German leaders boasted that their fortifications and coastal defences along the Channel and Atlantic Coast were impregnable. Parties of press men were escorted around some, especially those outside Calais and Boulogne built by men of the Todt Organisation – the Nazi civil and military engineering group made up of forced labour from occupied countries – who also built bomb-proof shelters of steel and concrete for housing ‘U’boats. These new massive guns along the French coast were housed at the entrances to natural caves and in other strong positions and surrounded by generally heightened defences.

The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was offered Honorary Freedom of Dover in September 1943, which was accepted. Churchill had already been offered the post of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and again this he had accepted but on both counts made it clear that he would not take up the positions until peace returned. Sir Winston Churchill was installed as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1946 and was bestowed the Honorary Freedom of Dover in 1951.

For months, people in Dover and surrounding areas been hearing the steady drone of RAF and USAAF planes on their way to bomb German cities and hoped that peace was not too long away. However, on the evening of 21 January 1944 the German retaliatory Operation Steinbock started when numerous Luftwaffe crossed the Channel with the intention of bombing London. On the Seafront, the Home Guard manning the anti-aircraft (ack-ack) guns along with soldiers manning the batteries along the cliffs created, it was reported, ‘the biggest concentration of flak seen since the Battle of Britain.’ Thus, Operation Steinbock was not as successful as was planned with many of the aircraft being brought down long before reaching their targets.

Thus far, servicemen had manned the Admiralty Pier Turret Battery but on 1 April it was handed over to the Dover Harbour Board Home Guard to enable soldiers to be relocated for the Second Front. One officer and eight Home Guard servicemen were to be on duty at any one time so the contingent was supplemented by sixty men from the main Dover Home Guard. The day before an order had been issued by Sir James Grigg, Secretary of State for War, making the Seafront out of bounds for anyone without a special pass. The combined British and American Operation Fortitude had begun. This built on Operation Sankey and troop movements around the town increased considerably.

Dummy tank landing craft were constructed in what is now the De Bradelei Wharf shopping complex but at that time the building housed the Dover Harbour Board workshops. Along the Seafront concrete aprons and small piers were constructed and a fleet of the hoax landing boats were moored alongside and in the Bay. Members of the Home Guard erected specially stencilled signs at road junctions and next to field gates, supposedly to help troops orientate. To add to the deception, official meetings were held at Dover’s Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu, to discuss dealing with washed up bodies following landings in Calais. In February 1944, General Montgomery attended one of these meetings and addressed the troops in Dover.

Local historian Joe Harman was a member of the Home Guard at the time, and he recalled going on a motorbike, out to Lydden in the line of duty. When he reached the plateau along Swanton Lane where there was an emergency airfield, he saw a great deal of activity with planes taking off and landing. He later found out that the exercise consisted of a few planes that after take off were flying away from the field in one direction and returning from another, only take off again after refuelling etc. This was to give the illusion of a lot of activity, as Joe had initially surmised, but of importance was that these movements would appear as a considerable number of blips on the enemy radar screens in France!

D-Day Landings June 1944 from the base of Admiral Bertram Ramsay statue at Dover Castle. Alan Sencicle

While all of this was going on, the Germans stepped up their attacks on Dover wreaking death and destruction. Then, in the early hours of Tuesday 6 June General Dwight Eisenhower (1890-1969), the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied forces, gave the ‘Go’ to Operation Overlord – the Normandy Landings. The Allied Naval Commander in Chief was Admiral Bertram Ramsay and throughout the day, as Allied ships traversed the Channel, minesweepers and coastal craft were looking out for both submarines and mines as well as laying smoke screens. In France, the Germans batteries were in full operation bombarding the Channel and the town of Dover constantly.

To add to the carnage in Dover, on 13 June the first of the VI pilotless flying machines propelled by rocket motors and carrying 1-ton warheads appeared. When the motor stopped those who were in earshot knew that they were likely to be the victims but had little time to seek shelter. A heavy concentration of ack-ack guns, many handled by the Home Guard, brought many down but it was the arrival of the US 127th AAA Gun Battalion at Swingate that had the greatest impact. The Battalion was equipped with four remote controlled 90-milimetre guns, linked to radar and an early form of computer that dealt effectively with flying bombs. Swingate, however, was open and therefore vulnerable to cross-Channel shelling and the Germans took advantage of this.

As the Allied Armies worked their way along the French coast from Normandy the launching of flying bombs and shelling of Dover and East Kent increased. The last flying bomb was from Calais on 1 September but the shelling continued to increase as if the Germans wanted to get rid of all their ammunition before being overrun. Although the town had become used to its ‘Hell Fire Corner’ image, what was happening and what was still to come was the worst of the whole War. Day after day, night after night, the shelling continued, Wednesday 13 September was no exception and shortly after a train arrived at Priory Station a shell exploded killing service personnel, civilians including a child and a police officer. Buildings at Charlton Green ceased to exist and others were badly damaged, including the school. What gas, water and electricity were still functioning ceased and in Kearsney Avenue on duty Home Guard John Price was killed.

Castle Street following the last shell to hit Dover on Tuesday 26 September 1944. Kent Messenger. Dover Library

Although the battering did not let up, Dover folk were aware that only twenty-miles away, across the Channel, the Allies had reached the Pas de Calais and were closing in. This was interpreted by journalists, working from their London offices, that Dover was no longer under attack. Those that actually ventured down to Dover had a rude awakening when they arrived in the, by now, wrecked town, to have shells whizzing past them. The nightmare continued until Tuesday 26 September when the bombardment was savage from just after midday until late afternoon. Over 45 shells fell on the town and although a lot of buildings were hit there were only four casualties. The shelling then stopped and the All Clear was sounded. Two hours later, the again sirens again shrieked and a solitary shell came in at 19.16hours. This hit Hubbard’s umbrella shop in Castle Street, destroying the shop and adjacent premises. Then, that was it! Four years of Hell were over! In the last 26 days, from the 1 September, 500 homes had been destroyed and 1,500 had been seriously damaged in the town!

At first there was disbelief, when the bombardment ceased, then tentative celebrations, when the truth eventually dawned that it had ceased the real celebrations started! Dover Home Guard after four years in the most exposed part of Hell Fire Corner were relieved of duty and on Wednesday 18 October George VI and Queen Elizabeth came to Dover to inspected Civil Defence workers. Some of the original members of Dover’s Home Guard were present at the event in the Town Hall. Of the original members, only sixty were left, those who had left had been called up to serve in the Armed Forces, were past the age requirement or because their industry had been relocated out of town.

The previous Sunday, 15 October, over 3,000 officers and men of the Kent Home Guard had attended a ‘stand-down’ thanksgiving service at Canterbury Cathedral. The final stand down was on Sunday 3 December, when the Dover Company was honoured by the town being selected as the venue of the final parade of the 8th Cinque Ports Battalion. That day the rain poured but 600 Home Guards assembled on the Seafront where they were addressed by the Commanding Officer of the battalion, Lieutenant Colonel R.W.Brent They then marched to St Mary’s Church, headed by the band of the Royal Marines. After the service, the men formed up on Biggin Street, and with the band leading them, they marched back to the Seafront. There the salute was taken at Cambridge Terrace by Colonel W.H.D. Wilson, Home Guard Commander, East Kent. Forming up in a line abreast, Lieutenant Colonel R.W.Brent gave the Battalion the order ‘DISMISS!’ for the last time.

Nearly a thousand men, ineligible for military service, were at one time or another members of the Dover Company. The British Home Guard was finally disbanded on 31 December 1945. Members had won two George Crosses and thirteen George Medals but 768 were killed during the War and 5,750 were wounded. Approximately 50 civilians were killed by members of the Home Guard. Following stand down, all the male members of the Home Guard were issued with certificates and on request, Defence Medals. After campaigning in 1945, women volunteers received certificates. Later, Winston Churchill wrote, ‘If in 1940 the enemy had descended suddenly in large numbers from the sky, he would have found only little clusters of men mostly armed with shotguns…’

The last missile to land near Dover was a V-2 rocket which exploded five miles off Shakespeare Cliff on 27 February 1945 and Dover’s last alert was sounded at the end of March that year. During the years 1940-1944 the enemy dropped 464 bombs on Dover borough and 2,226 shells crashed down on the town between 12 August 1940 and 26 September 1944. There were also three parachute mines and 1,500 incendiary bombs. Just over 3,000 alerts were sounded of which 2,872 were giving warning of enemy aircraft and 187 after shells had landed. The very high speed of shells gives little or no advance warning. As a result of the raids, 216 civilians were killed, 344 severely injured and 416 slightly injured. In total 957 homes were destroyed, 898 seriously damaged and 6,705 were less seriously damaged. Public buildings, general businesses and industrial premises were also destroyed or badly damaged.

Home Guard having officially stood down in December were part of the victory celebrations at Crabble Athletic Ground in 1945. Jim Davis

Following the end of the War in 1945 a special celebration was held at Crabble Athletic Ground. There, the Dover platoon of the 8th Cinque Ports Battalion, in front of townsfolk, took a final salute to those they had helped to defend against all odds during the War. On standing down, former members set up a rifle club using a 25-yard range in Trevanion Street caves. These are near the present Swimming Pool and had been used as air-raid shelters in the War. The club chairman was Norman Sutton, Editor of the Dover Express. In 1961, due to flooding at the Trevanion Street range, the Dover Home Guard (1944) Rifle Club joined with another local rifle club to become the Dover and District Rifle Club. The Admiralty and the War Office, on 18 September 1945, handed back to the Harbour Board most of the harbour they had controlled from 1939. On 30 November 1946, Dover ceased to be a naval base.

The Cold War (1947-1991) blew in during 1947 and with it a new threat, this time from the Soviet Union. In May 1949 a Parliamentary Committee was set up to look into the possibility of re-establishing the Home Guard and this was taken up by Winston Churchill, when he became Prime Minister in 1951. The organisation became effective with the Home Guard Act of 7 December that year and recruitment started on 2 April 1952 with the aim of enlisting 170,000 men in the first year. The 8th Kent (Dover) Home Guard was formed under Lieutenant-Colonel Cecil Lines, with headquarters at the Drill Hall on Liverpool Street, but recruitment was slow.

Nationally the picture was no different with only about 25,000 men committing themselves plus a further 21,000 agreeing to join if an emergency arose. As the fear of a nuclear war gripped the nation, more joined but still not sufficient and in 1956 the Home Guard were put on the Reserve List. On 31 July 1957 they were disbanded altogether. That year saw the long range guns that had defended the town during World War II broken up, the coastal artillery disbanded and railway lines serving the gun sites dismantled. In 1968 the first episode of the highly popular television series Dad’s Army was broadcast. It ran until 1977 with 80 episodes, a radio version based on television scripts, two feature films and a stage show. Confirming that the Home Guard had a place in the country’s memories.

Frontline Britain memorial to those Civilians and Services killed in East Kent 1939-1945 – Dover Seafront. Unveiled by Countess Mountbatten of Burma 20.09.1994. LS

Albeit, there is one aspect of the Home Guard over which little consideration has been given but sums up that first and foremost, the Home Guard were soldiers defending Britain during World War II against all odds. It concerns one of those 768 members of the Home Guard who were killed in line of duty and centres on his Estate. Home Guard, Frederick Mirrielees was killed when a hand grenade was accidentally dropped on 17 August 1940. At the time a regular Army Sergeant was giving instruction and it was he who had dropped the grenade. The Inland Revenue treated all the Home Guards’ Estates when killed in the line of duties as those of civilians and demanded death duties – taxes on the decease’s Estate. The Mirrielees family lawyers argued that under the Finance Act of 1891 the Estates of common members of the armed forces killed in action were exempt from death duties. The Inland Revenue retaliated by saying that Mr Mirrielees had been appointed company commander within his platoon but, argued the Estate’s lawyers, in the Home Guard there was little difference in the duties performed by officers to those of the common members. They were all soldiers who were doing the job for King and Country without financial recompense. Needless to say the Inland Revenue found this amusing saying the Local Defence Volunteers were just that, volunteers … amateur soldiers, Dads Army playing at soldiers but in reality, civilians.

Government Information recruitment advert for the Local Defence Volunteers May 1940 later the Home Guard. Doyle Collection

The case wended its way through the full British legal system ending in the House of Lords in October 1944. There, the Lord High Chancellor (1940-1945), John Allsebrook Simon (1873-1954) ruled that by Statutory Rules and Orders 1940, Number 748 dated 17 May 1940, ‘members of the then Local Defence Volunteers later the Home Guard, should be subject to military law as a soldier.’ He went on to say that a ‘soldier is one who risks his life for the defence of his country; and no other characteristic of his calling carries any comparable weight in defining it. It is in public acknowledgement of this dedication that he enjoys any privileges that the law allows to soldiers. In this case the testator’s life had not only been risked but given; and the law and the nation would have been churlish indeed if they had denied a soldiers rights to one who had died a soldiers death.’ House of Lords 9 October 1944.

- Presented: 5 April 2016