Town Planner, Professor Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957) in 1928 provided East Kent with a plan to meet what was then believed to be a dramatic expansion of the Kent Coalfield. The economic depression of the 1930s put an end to those dreams, but from the Professor’s plan the villages of Aylesham, Elvington and Hersden along with Mill Hill, in Deal, developed.

Dover, during World War II was not called ‘Hell Fire Corner’, for nothing and in 1943, Dover Corporation worked on a plan for reconstruction when peace came. In the event the situation did not abate and following the D-Day landings (6 June 1944) and while the

Germans were being driven out of France, the attacks increased. These intensified as the Canadians were closing in on German gun emplacements along the Pas de Calais.

German soldiers, in their heavily fortified emplacements, seemed to want to use up all their ammunition before surrendering. According to an American reporter the, ‘attacks increased to such intensity at the end of August and throughout September as to be very like the bombardment of a city under siege.’ On Tuesday 26 September, more than 50 shells were fired at the town and at 19.15hrs a shell hit Hubbard’s umbrella shop, Castle Street, destroying it and the adjacent premises. This was the last shell of World War II to hit Dover and do any material damage. The replacement building has a commemorative Dover Society Plaque.

When the shelling ceased it was estimated that the war damaged sustained by the town was proportionally greater than in any other town throughout the country. 957 houses had been destroyed; 898 seriously damaged but in part fit for uneasy habitation; and 6,705 were less seriously damaged. Public buildings, general businesses and industrial premises were also badly damaged.

Dover’s Town Clerk, at the time, was solicitor James Alexander Johnson, known as James A. When he was appointed in December 1944 he had already earned a name for himself as having a brilliant incisive mind and dogged determination. James A. was to use these skills to propel the reconstruction of Dover, based on the plans drawn up by Dover Corporation.

To give weight to the proposal Professor Abercrombie was hired for a fee of 1000 guineas (£1,050), to produce a Reconstruction Plan from which the Council could, ‘proceed systematically over the next twenty years … (and) … which will beautify Dover and make it worthier of its ancient heritage.’

Immediately the Professor submitted an ‘Area of Extensive War Damage’ application to the Government. This was given affirmation in January 1946, at the same time as Abercrombie’s report was published.

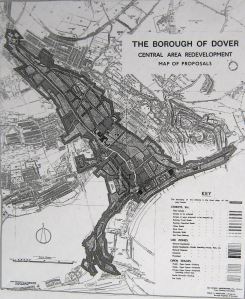

The report, described Dover as a long narrow valley with a series of steep hills on either side, opening onto a bay, with high cliffs at either side. Although Abercrombie recognised the importance of the harbour, the Professor said that ‘the lifeblood of a town of the nature of Dover is undoubtedly its industry.’ Two wide roads either side of the river Dour were proposed, which would accommodate the ‘out-district traffic and to provide access to the eastern and western harbours … whereon no shopping premises will be permitted.’

A new road on the east side of the valley was to be aligned with Barton Road to Frith Road, then through the Dover Girls’ Grammar school to Salisbury Road and Albert Road demolishing most of the properties. The Professor described the properties that had not been devastated during the wartime battering, as ‘of an obsolete design’ that ‘within 10-12 years will be near slums in multiple occupation.’

Charlton Green was to be the industrial hub of the town and would have easy access to the ‘homes of the workers upon the hillsides and nearby valleys.’ In order to dispel the expected squalor and unattractiveness of the industrial Charlton Green area, the Professor advocated ‘an open space around the beautiful Church of St Peter and Paul.’ The workers homes were to be Council built and on the upper slopes of the Buckland, St Radigunds and Aycliffe valleys. Elms Vale and River were to be developed along more select lines by private builders.

In the middle of the town, between Brook House and Maison Dieu House, would be a Civic Centre. The two ancient Houses, both damaged due to the war and years of neglect, were to be repaired and protected. Brook House was to be refurbished as museum and Maison Dieu House was to become the town’s library. The nearby 12th century chapel of St Edmunds on Priory Road would be restored and made a feature, ‘within lawns and gardens’.

This was particularly important to prestige of the town, for following heavy shelling on 24 August 1943, a newsagents and tobacconist shop in Priory Road was wrecked. When the ruins were cleared, St Edmund’s Chapel was seen for the first time in four hundred years! For many in Dover this was seen as a message from God. In a pre-James A Johnson report by the Borough Engineer, Philip Marchant, it was proposed to restore the Chapel as a war memorial and the major feature of post-war development.

A town feature that was implicit throughout Abercrombie’s report was the 4-mile long river Dour. His report recommended the opening of ‘the banks for much of its length, with the ultimate object of securing a pleasant riverside walk from the Sea Front to Kearsney Abbey.’

At the southern end of the town, near the sea, would be the main shopping precinct, ‘undisturbed by other than local traffic and within easy reach of the Omnibus Garage and Station and the service routes.’ The Seafront according to the Professor represented ‘the front door’ of the town and recommended the demolition of East Cliff and Athol Terrace and replace by a wide access road to the Eastern Dockyard. The war devastated Marine Parade was recommended to be replaced by marine gardens.

Waterloo Crescent was to remain and repaired but all other buildings on the west side of the Seafront were to be demolished and replaced by blocks of flats – the Gateway Flats – and residential hotels of ‘high quality, six and eight storeys in height.’ The then Pier District, which included the present Snargate Street, was to be razed and replaced by ‘pleasant gardens and open spaces, so that the full grandeur of the Cliffs may be revealed.’

Abercrombie’s report finished by saying, ‘With vision, courage, determination and faith, and with the good-will and sympathetic understanding of our friends, the building of a better and more beautiful Dover can, and will be, achieved for the lasting benefit of posterity.’

The Professor’s Plan went before the Council in February 1947, who having made some modifications asked the Government for a Declaration Order. This covered 252 acres, extending from Buckland Bridge to Charlton Green to the Seafront. The proposals were fully supported by the Town Clerk, James A Johnson, who put forward the argument to the Government Inspector. He also asked for immediate Compulsory Purchase Orders for the Seafront and other parts of town and made light of objections regarding saving what was left of Dover’s heritage.

In November 1947, James A’s proposals were confirmed excepting areas around the war-torn St James’ Street – the logic of which was lost on everyone concerned. Demolition began in 1948 and many attractive ancient buildings that could have been repaired and would have been of benefit to the town today succumbed to the bulldozer.

Published:

- Dover Mercury 20 & 27 April 2006