Biggin Street looking north 1930s, the man walking towards the camara is approximately outside what was no 6 where the Dover’s first public library opened in 1935. Hollingsbee Collection Dover Museum

It had taken almost 100 years to get a public library in Dover and this opened on 13 March 1935 at 6 Biggin Street – 85 years after the introduction of the first Public Libraries Act of 1850. The Act had permitted councils to use ratepayers’ money to provide a building, light and fuel and employ a librarian – further details can be read in Part I of the Library story. Subsequent to the 1850 Act, there were several more designed to encourage towns and cities to set up Libraries but in Dover, these were ignored. The main reason given was that ‘a free library was a luxury that the ratepayers of Dover could ill-afford and that the ratepayers already contributed 1pence in the £ towards elementary education, which many saw as a waste.’ (Cllr. Birkett 1913) – A view echoed today (2015) in regards to the future of Dover’s public library.

When Dover’s first municipal public library opened on that spring day in 1935, it was under the auspices of Dover Borough Council. William S Munford Bachelor of Science, aged 23, was appointed Dover’s first public librarian. The capital cost of the building was approximately £7,000, with an expected annual expenditure of about £3,000. The library was stocked with over 7,600 books and in the fortnight before opening 900 people had registered as readers. Immediately after the opening, people queued to enrol and two weeks later 19,641 books had been issue. It was commented in the local press that a centenary party should have been held, as it had taken that long to get the facility that people obviously wanted!

In his annual report a year later, Munford said that the number of readers registered was 12,262 amounting to 29.5% of the town’s population. The average percentage of readers to population over the whole country was 16.7%. The number of books issued in the previous year was 366,106. Concerning classification, the most popular books were fiction especially modern (79.5%) followed by geography and history (5.6%) then other non-fiction. The reference library contained three special collections, 234 books about Dover, 864 books on Kent and 239 on Dickens. The Dickens material was a gift of William Barnes (c1850-1942), the Dover Corporation honorary librarian at the Museum. Munford went on to say that following the opening of the library, the Carnegie Trust had given a grant of £650 spread over three years to buy books.

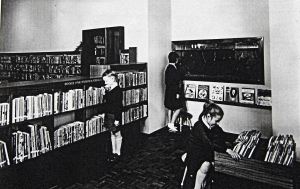

Munford reported that since the opening of the adult library, having acquired 1,300 children’s books a junior library had opened. It had been said that children would not be interested in books but 2,933 children had registered and the number of books had since been increased to 2,638 and more donations were desperately needed. Children, he went on, preferred non-fiction to fiction and all told, the number of issues in the year amounted to 62,460 books. Further, the junior library was increasingly being used as a study room as well as a resource centre. The following year Munford issued the library’s first magazine, ARGO. Named after the ship, in Greek mythology, when Argonauts went to seek the Golden Fleece. Designed to establish closer contact between the library and its readers it gave accounts of recent additions to the book stock. Proving popular, ARGO was issued four times a year and was free to readers at the library.

On 5 January 1938, Munford told the local press that the library contained 20,000 volumes and its millionth book had been issued! His annual report, published in May, stated that the percentage of readers to the population was 26.7%, still significantly higher than the country’s average. That modern fiction remained the favourite at 76.6% of adult books issued, followed by history and geography, social science, literature, fine arts, technology, science, and biographies. Young people still preferred non-fictional books but there was a significant trend towards classic and adult adventure books in preference to books aimed at children.

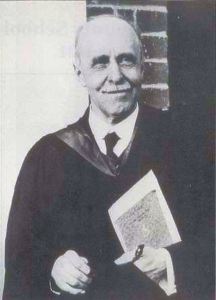

Fred Whitehouse Headmaster Dover Boys’ County School who successfully put forward the argument for a public library in Dover

In January 1939 Fred Whitehouse, who did a great deal to establish the public library in Dover, died and the library closed on the day of his funeral so the staff could attend. On 3 September 1939, World War II (1939-1945) broke out and from May 1940 until September 1944, Dover became Hell Fire Corner. With the influx of armed forces personnel, the demands on the library increased significantly and the YMCA introduced a mobile library van, provided by the British War Relief Society of USA. This worked in conjunction with the library and made weekly visits to the various gun batteries etc in the Dover area.

A large bomb fell at the rear of the library building on Maundy Thursday, 2 April 1942, causing a great deal of damage. Although the building was beyond repair, the library staff worked throughout the Easter weekend rescuing most of the books and furnishings. Temporary premises were found at 16 Effingham Crescent, where the library opened two weeks later. At about the same time, the slipper baths were removed from Biggin Hall and it was planned that the library would move in. For a variety of reasons, it stayed in Effingham Crescent. On Tuesday 26 September 1944 more than 50 shells were fired at the town, this was the last day of the four-year bombardment.

When the shelling ceased it was estimated that the war damage sustained by the town was proportionally greater than in any other town in the country. A reconstruction plan had already been drawn up and Maison Dieu House, at the time the Borough Engineers’ offices, was to be the new home for Dover’s public library. In October 1945, the library moved from the house in Effingham Crescent into Biggin Hall. About the same time, William Munford resigned as Dover’s librarian to take up the post of Cambridge City librarian and was succeeded by Bernard Corrall.

Biggin Hall proved to be totally inadequate through lack of space. To help the situation the junior library was moved to one of the Museum’s rooms under the then Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu. To make room for the junior library, the town archives and local book collections held by the museum were stored in a lavatory cubicle at Ladywell police station! Nonetheless, Bernard Corrall managed to reintroduce the pre-War successful quarterly magazine in spring 1947 and renamed it ‘New Leaf.’ However, in his annual reports Corrall was not complementary about the facilities at Biggin Hall. Indeed, in his report of 1948, he wrote, ‘We now operate under the most trying conditions, as you know and where all activities from the consulting of reference works to the borrowing of novels and the reading of periodicals all takes place in one room.’

In July 1948, the Town Clerk’s department moved from Brook House to New Bridge House, or Harbour House as it was then known. The council decided, in May 1949, to apply for a loan of £1,750 for repairs and adaptations to Brook House for the use by the Borough Engineers department’s staff and the move to Maison Dieu House became a step nearer. However, Maison Dieu House – a scheduled Ancient Monument – was in a bad condition as the result of war damage, death-watch beetle and ‘nails having been driven into walls and woodwork to hang things on.’ The council took a vote on whether to demolish the building and go for a purpose built library or whether to preserve the Jacobean House and adapt it for a library. With a vote of six to four, the latter was agreed and an application for a loan of £5,000 was made to the Ministry of Health.

Special bricks, made by Hawkinge Brickworks, were used for the repairs, the building was strengthened using weight bearing steel and ‘tying the front wall into position’. The floor covering in public rooms was cork and in staff rooms, the areas were either covered with linoleum or needle loom felt carpeting. Most of the furniture came from Biggin Hall with only shelving and racks being new. Wood facing in public rooms was first quality oak and African hardwood in staff only areas. Low-pressure gas fired hot water central heating was installed with the boiler housed in a separate building. The main lending library was on the first floor. This was chosen as the room had previously been divided into 6 by poor quality partition walls and so were easy to remove. The ground floor walls were part of the structure and could not be removed.

Mayor Bill Fish welcomes Lady Cornwallis before handing her the silver key to unlock the library door at Maison Dieu House. Dover Express 13.06.1952

The cost of war damage, conversion and equipment came to £10,181 of which £3,000 came from war damage grants. The refurbishment was started by Philip V Marchant, Borough Engineer under the direction of the Ancient Monuments branch of the Ministry of Works, and completed by his successor, David R Bevan. A loan of £3,500 was raised to purchase books and on 11 June 1952, the new library was to be formally opened by the Lord Lieutenant of Kent, Col Wykeham Cornwallis, 2nd Baron Cornwallis (1892-1982). Unfortunately, he was not well, so his wife Lady Esme Cornwallis took his place. The library had a total of 25,000 books and in September that year, librarian Bernard Corrall reported that a thousand books a day were being issued, the highest since 1936.

The junior library remained in the basement of the Town Hall but the old library premises in Biggin Street, by that time, had been demolished. On the site and adjacent sites, in 1955, the buildings on the east side of Biggin Street, below Maison Dieu House, that we see today had been erected.

In July 1956, a new Dover Corporation Act received Royal Assent. Its main purpose appertained to buses and the repeal of sections of an old Act, which made owners of East Cliff properties liable to the cost of maintaining sea defences. As with such Bills, the council took the opportunity to include other provisions. On this occasion, a provision to charge fines on non-return and overdue library books.

The library was becoming increasingly more popular but many of those who wished to join lived outside of the Dover boundaries. Concessions were made and at the same time the council pressured Kent County Council (KCC) to pay for these borrowers. In the end, KCC agreed to a one off payment but this was not acceptable to the council and so both sides returned to the negotiating table. The 1961 annual report for Dover Library stated that 86,305 non-fiction books had been issued that year and the number of fiction books was 193,112. The total number of books issued was 23% higher than ever before. The junior library, on the other hand, had trouble attracting interest for which, Corrall – Dover’s librarian – blamed wholly on the cramped, inappropriate location.

A site in Maison Dieu gardens opposite the bowling green was earmarked for a junior library in 1961 and £9,000 was set aside. However, there were loud objections pointing out that the children’s library in the basement of the Town Hall was hardly used. Further, the vociferous middle class residents of Dover said that the main reason that their children did not use the libraries was because they could get all the information and entertainment they needed from the radio, television and gramophone records. Libraries were for ‘old fuddy-duddies’ and their children ‘wouldn‘t be seen dead in the public library!’ So the junior library project was postponed and the widening of Biggin Street, opposite new shops that were to be built (at the time Tesco’s and up until recently Dorothy Perkins) was given priority.

Eventually, the purpose built junior and teenagers library opened, with great pomp, on Wednesday 20 November 1963 by Mayor Cyril Chilton. One of the children shown in the publicity photographs taken on the first day was the offspring of the ‘middle class complainer who had been reported as saying that her child would not be seen dead in the library,’ cited above, but asked not to be named!

During the War L R McColvin, the City Librarian of Westminster, undertook a survey of the country’s libraries and found a wide variation in standards, with poor book stocks, inadequate staffing, unsuitable buildings and a general lack of cooperation and enthusiasm. ‘Economic factors tend to be too strong to permit the maintenance of an efficient library service,’ was his conclusion. This became the basis of the Roberts Report on County Libraries of 1959, when they found that little had changed.

The government in 1957 had appointed the Roberts Committee to look at the Public Library services and they recommended that every public library should have a statutory duty to provide efficient services. That the Minister of Education should oversee the service and appoint two advisory bodies, one for England and one for Wales, to assist him. In 1962, a working party was appointed by the Education Minister, Sir Edward Boyle (1923-1981) and chaired by H T Bourdillion. Using the Roberts’ recommendations as a basis, resulted in the 1964 Public Libraries and Museums Act that briefly stated Local councils had to abide by the Public Libraries Act, which makes public library services a statutory duty for local authorities and that Councils must:

- Provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons in the area that want to make use of it.

- Lend books and other printed material free of charge for those who live, work or study in the area.

The government was to superintend the councils’ role and had a duty to oversee and promote the public library service and take action where a local authority fails to perform its duties.

Under the new Act, inspectors checked out libraries. Following Dover’s inspection, the library was held up as an epitome of a small town library. However, there were some comments made over inadequacies due to the constraints of the building. Due to rising costs and cutbacks, the quarterly newsletter, New Leaf, ceased to be published following the 1965 March edition. It was replaced by a monthly duplicated sheet advising on latest additions of books and any changes within the Dover library services.

In 1965, together with the museum, the recently formed New Dover Group (now Dover Society) and backed by more than 50 local firms plus all the local schools, the Dover Library organised the Dover, Past and Present exhibition in the Connaught Hall. This proved so successful that in 1971, when local photographer, Ray Warner and local historian, Ivan Green launched the Annual Dover Film Festival a concurrent exhibition was put on jointly by the museum and library. The annual Dover Film Festival is still popular today.

Dover’s chief librarian, Bernard Corrall, retired in 1966 and was succeeded by Tony Ricketts. Asked, by the council to provide a synopsis on how the library should develop, Ricketts’ made three suggestions. The first was the introduction of a record library at a charge of 1shilling (5pence) a record for 2 weeks borrowing. Ricketts’ pointed out that classical records, in shops, cost £5, which was a lot of money to spend by someone who had heard a piece only once and would like to hear it again. He said that new, replacement records, could be bought out of the charges levied and he envisaged the initial overall cost to be £1,500.

Ricketts second suggestion, was that there should be a Local History Department. The town, he said, had a considerable store of ancient documents, deeds, and local history books and some of these were available to readers in the reference section of the library. If there was a special room with restrictive access and supervised by a specialist librarian, most if not all could be made available and that he was sure this would prove popular. Finally, Ricketts suggested a mobile library service for the disabled and those who lived more than a mile from the library. This, his predecessor had long argued for, and he was aware that a vehicle was been considered. It was less than two years later, in January 1968, that the mobile library van was introduced to serve Dover and outlying areas including Crabble and Kearsney. Before 1974, the other two of Rickett’s recommendations were introduced.

The 1972 Local Government Act led to the formation of Dover District Council (DDC) on 1 April 1974 and from this date Dover’s library came under KCC. With this, the ownership of Maison Dieu House, Dover’s books and records were transferred to KCC. At the time, the library facilities and services provided included:

- Lending, reference/information, children’s section, meeting rooms, collections of periodicals, record library, technical and commercial literature, international documents, a full and documented range of archive and local history room and materials.

- Support for smaller village libraries by providing a basic lending reference/information service.

- Mobile library taking books to the aged and housebound, to hospitals, persons and others that were unable to reach the library.

- Activities such as lectures, exhibitions and displays that helped to advertise the library services to a wider public. Also a thriving local studies and cultural centre where local historians could share their expertise and encourage others to share the interest.

- Working closely with local schools and colleges, industry and other institutions such as the then Young Offenders Institute on Western Heights.

- Providing technical information services and special collections for the use of groups, such as dramatic societies, workers educational associations and local history enthusiasts.

Tony Ricketts was appointed the group librarian and his domain included the local villages, however the quarterly newsletter New Leaf ceased. Three years after reorganisation, the village libraries of Alkham, Capel, Church Hougham, Guston, Kingsdown, Langdon, Ringwould, Staple and Temple Ewell were closed. The mobile library van routes were extended, as this was seen by KCC as a more efficient way of serving rural areas. The old Dover Corporation van was replaced in June 1981 with a £18,000 mobile van.

By 1980, the number of LP records borrowed was in decline, but the borrowing demand exceeded the footfall into the local studies section. The record collection was moved to a different part of the library and loaning was extended to include audiocassettes. CDs were included shortly after, videos in the 1990s followed by DVDs during which time the LPs had ceased to be stocked.

Group librarian, Tony Ricketts suddenly died in August 1988 and Gavin Wright was appointed. He held a post-degree diploma in Librarianship and had worked at Dover library for five years. November 1988 saw the 25th anniversary of the opening of the junior library and it was reported that during that time 1,500,000 books had been borrowed. Over 2,000 children from 14 Dover schools attended the celebrations. Two years later, schoolchildren along with old age pensioners lost the ‘no fines’ concession for overdue books but it was agreed that librarians could use their discretion.

Dover museum had been in the cramped basement of the Town Hall since the War, but in 1989, it was moved to the purpose built premises in Market Square. This was behind the preserved facade of the old Market Hall and next to what was expected to be the iconic White Cliffs Experience. The museum library was, and still is, on the first/second floor in a very narrow room immediately behind the facade. All the time the museum was in the overcrowded Town Hall basement, most of Dover’s ancient documents had been looked after by the library. When the new museum opened, instead of going there, the ancient documents were moved to the newly opened Local Studies facility in Maidstone.

A new specially converted mobile library was introduced in 1990. With glass panels in the roof to provide better light, while inside the van was a paperback carousel for teenage stock, a seating area alongside the picture books area and its own heating system and built-in washbasin. The van called at 63 stops in the district and carried 25,000 books. During the previous year 69,000 loans had been made from the mobile van. In February 1993, a £200 induction loop system for the hard of hearing with hearing aids was installed and paid for by the Dover Club for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. At about the same time, the Dover Lions provided the library with an ‘easy reader’ to help users with eyesight problems.

However, there was talk at government level, of making public libraries financially self sufficient. At the same time, at the local level, a lot of the library books were put on sale as, it was said, a major refurbishment was in the offing. After many years of agitation to provide disabled access to the upstairs main section of the library, in September 1993 the library underwent major structural work and refurbishment. The building is Grade 2* listed and special permission had to be gained for the installation of a lift. The work closed the library for 9 weeks, cost £80,000 but before work started masses of books were sold. KCC councillor Paul Verrill cut the official tape to open the refurbished building. At the end of the year the quarterly newsletter, New Leaf was re-launched and replacement books made up for those that had been sold.

In the mid-1990s, the first PC was made available for public use in the library and in 1999 connections were made to the Internet. Two years later, in 2001, new computers with Internet connections were installed. At the end of 1993 this author’s book, Banking on Dover was published. Much of the basic research was undertaken at Dover library with the help from the Local Studies specialist, Trish Godfrey. However, because of the amount of Dover’s historic material that had been moved to Maidstone, a great many railway journeys had to be made.

Albeit, it was in that Local Studies room that my interest in Local History was born and fostered by Joe Harman, who became my mentor. It was there that I met, shared views and was encouraged by other local historians including, Tony Belsey, David Collier, John Douch, Sylvia Dunford, Bob Hollingsbee and Doug Welby. On 22 November, after my work was published, the library reopened and a special exhibition for my book was mounted. This was not unusual, as Gavin Wright did this for ALL local authors on publication.

Agitation by locals having to travel to Maidstone to view local archival material brought a change in October 2000 when a new archives centre opened near DDC offices at Whitfield. The collections that had been moved to Maidstone could be ordered and viewed. Records including those of Dover Corporations spanning seven centuries, Dover Harbour Board, the Cinque Ports Confederation, Courts and prisons amongst others, were available. Only open for two days a week both tables and archival material had to be booked in advance and one had to know exactly what one wanted, which was fine for seasoned local historians. However, KCC did say that it was committed to make such material even more accessible to all members of the public in the Dover area.

Queen Elizabeth II sent a letter of congratulation to Dover library on 11 June 2002, when the library celebrated its Golden Jubilee at Maison Dieu House. A special exhibition was mounted for the event with the publication of a booklet by librarian Keith Howell. The exhibition featured a Time Line with a photograph display from 1952 and the booklet, Maison Dieu House and Libraries in Dover given out free.

The White Cliffs Experience, adjacent to the Museum in Market Square, closed due to mounting losses on 17 December 2000. The building was sold by DDC to KCC for £1 and renamed the Dover Discovery Centre – for some odd reason to equate with the initials of Dover District Council! On Saturday 14 June 2003, the library at Maison Dieu House closed pending a move to the Dover Discovery Centre. Until the end of July a mobile library parked outside the former library had served the town. As had happened in 1993, masses of books were again sold but this time they were not replaced.

2003 the Junior Library is put up for sale but KCC gave the wrong address and the wrong building in the for sale advert!

On Monday 28 July 2003, the ‘new’ library opened to the public and was formally opened in September that year. As for Maison Dieu House and the junior library, both of which had been purchased by Dover Corporation using local ratepayers’ money, were put on the market by KCC. The asking price for Maison Dieu House was £400,000 and the junior library for £175,000. Further, in the advert for the junior library, not only was address wrong but the photograph was of the former Technical college!

In a letter from Sir Sandy Bruce-Lockhart (1942-2008) – Leader of Kent County Council and dated 31 July 2003. Sir Sandy said that KCC had invested £1.45m in the new Whitecliff Library – we assume that he meant the Dover Discovery Centre – saying that it would be a ‘flagship library’. He went on to say that Maison Dieu House was taken into account in raising the £1.45m and that it was agreed that KCC would sell Maison Dieu House to Dover Town Council for £310,000. The shortfall of £90,000 would come from both KCC and Dover District Council.

Letter from Sandy Bruce-Lockhart – Leader of Kent County Council outlining the sale of Maison Dieu House and the planned future of the library at Dover Discovery Centre 31.07.2003

Following the £1.45million make over of the former White Cliffs Experience, a ‘One Stop Shop’ was introduced by KCC to the Dover Discovery Centre. From observation and write ups in the local press, part of the library area and the remaining librarians dealt with bus passes, helped immigrants fill in official forms and registered births and deaths.

The local studies section of the library continued for a short while but a change in KCC policy from specialist to ubiquitous librarians meant further loss of valuable expertise. On 2005, the number of professional librarians across the county was cut by one-third. However, for the Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Dover library in 2006, ‘officials’ arrived giving the appearance of the well-staffed library of yesteryear.

A year later, plans were afoot for further cuts in the number of professional librarians. At the time KCC were responsible for 106 libraries across the county and a KCC representative was reported as saying that this showed a lack of efficiency. The areas to be cut back, besides libraries, were visits to schools and play schools, homework clubs, local history sections, local history events, author visits and IT sessions.

Pending the opening of the £12m, Kent History and Library Centre at Maidstone in 2012, on Friday 11 November 2011, the East Kent Archive Centre, at Whitfield closed. Since then, those interested in local history have to travel to Maidstone.

January 2014 saw a ‘makeover’ of what is generally known as the ‘dull corridor’ that led into the junior’s part of the library. Volunteers with the Princes Trust carried this out as part of a community project. The volunteers also funded the project by undertaking sponsored walks and general fund raising in Dover’s town centre.

At the beginning of Part 1 of this story on Dover Library, reference was made to the Dover woman who made it clear that Dover library should be allowed to close because neither she nor her children ever used it. One of the reasons she cited was that the library lacked modern technology such as Internet access. Although Dover library has been allowed to run down, as shown above, computers with Internet connections were introduced in 2001. Indeed, these are shown on the plan view of the present library published by KCC.

In 2011, locality boards were set up including, supposedly, one in Dover. The person/people involved were/are to enable KCC determine the best model for the library and, according to KCC Councillor Mike Hill, to ‘tailor the library services to the needs of each community.‘ To date, doverhistorian.com is not aware of any person claiming to be Dover’s representative. Further the KCC website does not refer to such representatives. However, in January 2015, KCC asked the people of Dover to accept a proposed public library that would be run by a Charitable Trust with a token financial backing by the Statutory Authority – KCC and staffed predominantly by volunteers.

On 18 December 2014, a report on the nation’s libraries was published. This was commissioned by the present government (to May 2015) and generally known as the Sieghart Report. Amongst other things – See Submission on the KCC proposal – the report stated that across England 35 per cent of people use a library regularly and ‘among the poorest it’s closer to 50 per cent. It’s a vital lifeline for a lot of people.’ Dover district has 5 of the poorest wards in the county. Statistically the library will be used by 15% more than a library in the more affluent towns.

Not only did KCC break the promise given by Sir Sandy Bruce Lockhart that Dover Public Library would become a ‘Flagship Public Library again’ as it was hoped, by those who care about the people of Dover’s future. Sadly, they preferred to listen to the woman with a lot of weight and her cronies mentioned at the start of Part I Library story. In May 2015 they announced that the people of Dover would have to travel to Maidstone to access full public library facilities.

- Presented:

- 16 March 2015