Henry III (1216-1272) ascended the throne when he was only 9 years old but like his father’s, King John (1199-1216), reign it was a stormy one. Following the Battle of Dover of 24 August 1217 (see Origins of the Cinque Ports and Dover Part I), the Cinque Ports mariners, known as Portsmen, settled back into earning their living locally. This was from the sea by fishing, ferrying people and goods across the English Channel and piracy. The latter they were able to get away with as the Court of Shepway was the only external court they recognised where the judges were all Portsmen! To try and put an end to the piracy, Henry in 1226, created the post of Warden of the Cinque Ports. At first the Warden, was jointly held by the Constable of Dover Castle, the Lord of Folkestone William d’Averanche at that time. The other person was the Prepositus of Dover who also acted as the Mayor of the town, Henry Turgis at that time. The role of the Warden, it was decreed, was to preside over the Court of Shepway and this the Portsman accepted.

From thereon, however, the Portsmen only accepted Royal orders or mandates from the Crown if they came through the Warden. This they were able to do as they provided Ship Service that was, effectively, the Royal Fleet of maritime England. The Cinque Ports were Hastings, Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich and their role, function and privileges were decreed by Charters. In 1229, Henry issued another Charter to the Cinque Ports that was subsequently lost. A copy dated 1300, was discovered in 1931 in New Romney. This stated that the five ports were equal in status and privileges but differed in the number of ships and crew they were bound to provide for Ship Service. As a whole they were obliged to supply 57 ships a year for 15 days with 20 men and a boy for each vessel and at the Ports expense. The Ship Service was divided with Dover and Hastings being obliged to provide 21 vessels each and the other three towns, 5 vessels apiece. If, however, the King wished to retain the vessels in excess of that period then he would pay the costs.

When Ship Service was first instituted, during the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), Dover was required to provide 20 ships and in order to comply, the town was originally divided into 20 wards with each ward providing a fully crewed ship. At different periods of time the number and names of the wards changed. By 1429, when the names were fully recorded there was 21, Bekyn, Burman, Bully’s, Canon, Castledene, Derman, Delfys, Deeper, Halfguden, Horsepol, Moryns, Nankyn, Ox, Snargate, Syngyl, St Mary, St George, St Nicholas, Upmarket, Werston and Wolvys.

It was evident from the 1229 Charter that Dover had a strong maritime presence and this was because in 1227, Henry conferred on the town the monopoly of the cross-Channel passage by royal charter, given with the consent of Parliament. It was enacted ‘that no pilgrims shall pass out of our realm to foreign parts except from Dover under the penalty of imprisonment for one year.’ The passage was, in those days, the carrying of passengers and cargo across the Channel to Wissant, France and proved to be a very lucrative source of revenue to Dover. Further, on 21 February 1173 the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket (c1119-1170) was canonised and pilgrims came from all over Europe to visit his tomb. Hence, because of the monopoly of the passage, the pilgrims stayed in Dover with the poorer ones at the Maison Dieu, before going to Canterbury.

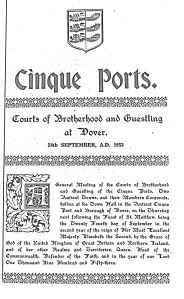

The position of Warden of the Cinque Ports was elevated to Lord Warden and in 1242 Peter de Savoy (1203-1268) the Earl of Richmond, received the first commission for the combined office of Lord Warden and Constable of Dover Castle. It was about this time that two other Cinque Port courts in addition to the Court of Shepway, were established. As they were set up by the Portsmen for the administration of the Cinque Ports they were independent of monarch and country’s judiciary. One of these was the Court of Brodhull, believed to be named after a village near Dymchurch, Kent that no longer exists and the other was at Guestling, Sussex. The jurisdiction of the Court of Brodhull covered only the Kent Cinque Ports and later the name was changed to Brotherhood. Initially, its duty was to control the Bailiffs who administered the annual Yarmouth Herring Fairs that the Portsmen had founded in Saxon times. Other areas regularly discussed were the Kent Ports’ Ship Service and Coronation obligations, a privilege that had been decreed in earlier Cinque Port Charters. The meetings were irregular and presided over by the Speaker whose appointment was, and still is, renewed annually in rotation by the Mayors of the Cinque Ports and their incorporated Limbs.

Generally equated with the Court of Brodhull was, and still is, the Court of Guestling, which was probably called after a village near Hastings of the same name. This Court seems to have been an informal gathering of the Sussex members of the Confederation plus the Antient Towns of Rye and Winchelsea. The subjects discussed included the provision of Ship Service, matters requiring remedial jurisdiction and inhibiting Frenchmen from fishing near the Sussex shore. Like the Court of Brodhull, the Guestling Court was presided over by the Speaker with the Mayors of the Sussex Cinque Ports, Antient Towns and incorporated Limbs, renewed annually in rotation. For centuries, the meeting of port representatives in one county would be followed a few days later by those of the other. The Brodhull Court moved to Romney in the mid-fourteenth century and the proceedings of both Courts were entered into the ‘Great White and Black Bookes of the Cinqz Portes of England.’

Except for Dover, which had the monopoly of the passage, fishing provided the main livelihood for the Cinque Ports. However, as Henry had, up until the founding of the Courts of Brodhull and Guestling, called the Fleet out in excess of their obligation under Ship Service. As he had paid for the privilege and the Portsmen were able to keep part of the booty, they were appeased. Nonetheless, they were increasingly relying on the proceeds of the Yarmouth Herring Fair for their main earnings. When, in 1242, Henry again called them out in excess of their Ship Service obligation, they were not happy.

The Portsmen’s ships, although of the same basic design, had increased in size which enabled them to carry sixteen or more horses plus knights and their retinue. The Portsmens order, on that occasion, was to take troops to France as Henry was planning to regain Poitou with the help of his brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort (1208–1265) 6th Earl of Leicester. Henry‘s brother Richard (1209-1272) had lost Poitou some 15-years before. Albeit, shortage of funds turned the exercise into a disaster and the Portsmen made their anger felt. In recompense, on return to England Henry ordered the Cinque Ports Fleet to ravage the French coast.

They carried out the order with gusto, attacking coastal ports from Calais to La Rochelle – cruelly robbing and killing English as well as the French. The French retaliated by changing the design of their ships and increasing their number. In consequence, towards the end of their pillaging spree, the Portsmen suffered defeats and were driven back to England. A truce relieved the situation and with it came prosperity such that in 1254, Dover, together with the other Cinque Ports, presented Henry with jewels and in return, the King granted Dover his share of the harbour tolls for the defence of the Castle.

Learning from the experience, by 1255, the Portsmen designed a new ship called a cog. This had a much larger clinker built hull than the traditional Cinque Ports ship and it also had a built up poop at the stern, a main mast, a bowsprit and later a mizzen mast. No longer needing to be navigated by a sweep – a large oar – off the stern quarter, it had a rudder. This meant that it was more navigable, performed better in rough seas and could sail much closer to the wind. However, like its predecessors, the cog did not have an anchor, instead the Portsmen filled fishing nets with stones that they threw off the bow. Later modifications included an anchor and together with changes in the rigging the cog design remained in service for several centuries. Further, as the ship relied entirely on sails it could carry much more cargo or/and troops, their horses, weapons and other goods that they required.

However, Henry’s concerns over land holdings on the Continent were becoming an increasing drain on the English economy. Like his predecessors, he raised money by increasing taxation that did not go down well with the country’s elite Barons. They owned castles, vast estates, provided Henry with troops but were powerful in their own right. They had tried to resolve the issues between Henry and the French King Louis VII (1137-1180) through diplomacy, but with little success. They therefore called upon Henry’s brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort to force Henry to surrender power to a Baronial led council.

Initially, Henry appeared to comply with the Barons but in 1261, he successfully gained a Papal Bull exempting him from the agreed resolutions and both sides drew up forces. The Lord Warden at that time was Richard de Grey (d1271) who resigned while the Portsmen sided with de Montfort. A succession of Lord Wardens came and went but the Portsmen remained loyal to de Montfort. At the beginning of June 1263, Nicholas de Crioll was given the post of Lord Warden with the main task of securing Dover harbour against the Portsmen on behalf of the King. After two weeks of skirmishes and brawls it was evident that de Crioll had failed.

The King’s second surviving son, Edmund (1245-1296), was appointed Lord Warden on 15 June but in August de Montfort reappointed de Grey. In December that year, with the help of the Portsmen, de Grey repulsed Henry’s eldest son, Prince Edward (1239-1307) who tried to take over the fortification. Sir Roger de Leybourne (1215-1271) had been a Baronial supporter but had been forced to forfeit his estates by Henry. However, Edward was his childhood friend and he managed to get a message to Leybourne promising the return of his estates if he switched sides. Leybourne raised a small army and seized the Castle releasing Edward.

Nonetheless, the Portsmen remained loyal to de Montfort and on 14 May 1264, supported him at the Battle of Lewes. There, Henry was defeated and he and his two sons were taken prisoners. De Montfort, with the help of the Portsmen, repossessed the Castle and subsequently the two Princes were held prisoners there. In exchange for Portsmen who had been taken prisoners by Royalist forces, Edward was released and immediately raised an army against de Montfort. He then laid siege to the Castle and when he gained control of the Keep, the Castle’s military force surrendered. In the meantime, Henry’s wife, Eleanor of Provence (1223-1291), was on the Continent collecting forces and preparing to invade. Thus, de Montfort asked the Portsmen to patrol the Strait ‘vigorously’, which they did, stopping so much merchant shipping that prices of coastal trade and imported commodities rose significantly. They also razed to the ground Royalist Portsmouth.

In February 1264 Leybourne went to France in order to escort Henry back to Dover and on landing marched with the King to Northampton. The Portsman took advantage of this taking possession of the Castle in the name of de Montfort. He appointed his son Henry de Montfort (1238-1265), Constable and on Leybourne’s returned he refused to allow him access. Henry recognising that the Portsmen would not capitulate gave Leybourne other appointments and they stayed. De Montfort summoned Parliament on 20 January 1265 and insisted that all representatives were to be elected. The vote was given to those who owned the freehold of land to an annual rent of 40 shillings (‘Forty-shilling Freeholders’) and the Cinque Ports and Antient Towns were represented by 28 Cinque Ports Barons – of no relation to the country’s Barons, but an ancient titular rank.

However, many of the Barons thought that the reforms were going too far and de Montfort’s allies started to defect to Prince Edward. Flying the de Montfort banners, Edward met de Montfort at Evesham, Worcestershire, on 4 August 1265, and thus leading him into a trap. Weakened by this, de Montfort, his son Henry and his supporters, including Portsmen, were defeated. From that time until Henry III died, (1272), Edward ruled England.

Stephen de Pencester – Lord Warden 1267-1297 – designed by H W Lonsdale 1892 for a window in the Maison Dieu. Dover Museum

As for Leybourne, he regained the posts of Constable and Lord Warden following the Battle but retribution was high on his list and he used it against the Dover and the other Cinque Ports. Prince Edward hearing of this, on 26 November, he relieved Leybourne of his posts and took them himself. Once in charge, Prince Edward received the Portsmen into the King’s grace, confirming their liberties and forgiving all homicides and depredations. By March 1266, the Prince was able to state that he had overcome the rebellion and resigned as the Constable of Dover Castle and Lord Warden.

The following year, Sir Stephen de Pencester (d 1303) was appointed Constable and Lord Warden. An administrator, Pencester collected and collated the Dover Castle Charter Book, which gave an account of the Castle rights, privileges and immunities since Saxon times. He then went on to lay out a set of Statutes for the efficient running of the Castle. This gives a unique insight into the daily life of the Castle at that time. He was also one of the witnesses of the Great Cinque Ports Charter of 1278 that Edward gave the Portsmen. Pencester also started the ‘Red Book’ listing the ships that each Port was obliged to supply and in 1293, he produced the first authoritative list of Cinque Ports Confederation Members. It is believed by some that Pencester Gardens were named after him.

Following his Father’s death in 1272, Edward I (1272-1307) ascended the throne though he was on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and did not arrive back to Dover until two years later. At the time, it would appear, the country was at relative peace with the Portsmen going about their business of fishing, providing passage and pillaging the French coast. When the King was crowned, the Portsmen Baron’s attended the Coronation and in 1274, the Cinque Ports Fleet was back in action. They were part of Edward’s campaign against the Welsh, creating a blockade along the coastline to prevent French supplies.

However, the demand on the Portsmen was in excess of Ship Service and this led to riots in Dover and discontent in the other Cinque Ports. Nonetheless, the demand for the Portsmen’s services, over and beyond the call of Ship Service, continued. In 1277, in order to appease the Portsmen, Edward granted them the rights of all plunder taken from the Welsh and the right to ransom all prisoners taken except those the King wanted for himself. The Portsmen inflicted and suffered heavy losses but overall they helped to secure victory and financially, did very well.

Cinque Ports Flag showing the three lions passant guardian conjoined to as many ships hulls. Stone Hall, Maison Dieu LS 2009

Further, in reward for the victory, in 1278, Edward granted the Great Cinque Ports Charter, that encapsulated all their duties, rights and privileges of the former Charters and effectively confirmed the Cinque Ports as providing England’s first true navy. Unlike previous Cinque Ports Charters, this one was a comprehensive and carefully written document, typical of Edward, and it was possibly this reason as to why it was treated with great honour. It was about this time that the Cinque Ports device of three lions passant guardian conjoined to as many ships hulls, came into use.

In 1282, the Portsmen were back in action off Wales, supporting the King, before aiding him in his forays into Scotland. On 13 May 1286, Edward and his wife Eleanor of Castile (1241-1290) left Dover, in a fleet of ships, including those of the Cinque Ports, to pay homage to Philip IV of France (1285-1314). Edward was the Duke of Aquitaine and therefore, regarding the lands that Edward held in Gascony, he was the French King’s vassal. Four years later Edward’s beloved Eleanor died but for political reasons, he was soon looking at Blanche (1278-1305), sister of Philip IV, as her successor.

Although England and France were on peaceful terms the Portsmen carried on pillaging the French coast when circumstances allowed. The extent of this was such that Philip complained and it was Edward who called a Commission of Inquiry. At face value, it would appear that the Inquiry found the Portsmen not to be as pugnacious as had been reported. In reality, as Edward’s exchequer received one-fifth of the Portsmen’s booty, the result was not a surprise! Albeit, the lie was exposed on 15 May 1293 when the Portsmen went on a pillaging foray along the coast of Brittany. The French were ready and engaged them in a sea Battle off Point St Mathieu, Brittany.

About 400 vessels were involved with the Portsmen holding their own, taking many prizes but not before throwing about a thousand Frenchmen overboard to their deaths. They then went on to ransack and raze Cherbourg and sack La Rochelle. Following the massacre Edward was ordered, as Duke of Aquitaine, to appear before Philip and explain. Edward refused. For punishment, Philip declared Gascony forfeit and Edward retaliated by embarking on an expedition to recover the province. A protracted war ensued during which time Blanche rejected Edward as a suitor.

Thomas Hale’s Murder at the Priory 1295 from the Life and Passion of Thomas de la Hale by John of Tynemouth 1377

On the night of Tuesday 2 August 1295, a French fleet of 300 ships landed a large force of soldiers on the beach under Western Heights. Dover was sacked, the houses burnt to the ground and the town folk slaughtered. Only the churches and religious houses survived the fire and they were pillaged. Anyone found within the religious establishments were also put to death. At the Priory the French could not find any valuables but did find Thomas Hale, a frail elderly monk. Although they tortured him, he refused to tell them where the valuables were hidden and was subsequently killed.

Coronation Canopy being carried by Cinque Ports Barons at the Coronation of Charles I. LS Collection

After dealing successfully with another revolt in Wales, Edward decided to try and retake Gascony and with the Cinque Ports Fleet, they left for France on 9 October 1295. To raise money for the expedition Edward had called a parliament but the Clergy and Barons refused financial help. Edward, therefore reconstituted parliament, taking on board many of the reforms that Simon de Montford had advocated. The new Model Parliament met on 13 November 1295 but as the Portsmen were away, the number of their representatives was reduced to 14, considerably less than the number de Montfort had advocated. In order to placate the Portsmen, Edward issued a mandate granting the right of the Cinque Ports Barons elected to Parliament, to carry the Canopy over the head of the sovereign at Coronations.

The Scottish King (1292 to 1296), John Balliol (1249-1314) made a pact with Philip of France in 1295 against Edward‘s wishes. In response, Edward gathered an army of 25,000, including Portsmen, one of which was John de Aula, from Dover. He commanded a division of Kentish men-at-arms. On 30 March 1296, Edward’s forces arrived at the border town of Berwick-on-Tweed, but the citizens refused to open the gate. The troops stormed the town and massacred nearly the whole population. Edward then marched his troops into Scotland forcing John Balliol to abdicate. The Cinque Ports Fleet was off the Scottish coast when they received the order to help the army to take on William Wallace (d1305) who was leading a counter attack.

At the same time Philip of France was in a hostile situation against Guy of Dampierre – Count of Flanders (1251-1305). Although the Count’s relationship with Edward was not good, he called upon the King for help. On 22 August 1297, Edward sailed for Sluys, (these days Sluis or L’Ecluse) Flanders (these days the Dutch speaking northern part of Belgium) with the Cinque Ports Fleet to wage war against Philip. The Fleet included ships from Yarmouth. Much to the annoyance of the folk of Yarmouth, their town was still under the control of the Cinque Ports and off Sluys, an altercation took place. The Portsmen burnt 20 of Yarmouth’s ships and in consequence, Edward’s mission was aborted. Instead of punishing the Portsmen, as the mariners of Yarmouth expected, the King granted the Portsmen another profitable Charter and the Yarmouth men were ordered to keep the peace!

The rebellion still raged in Scotland and at the Battle of Stirling on 11 September 1297, Wallace and his army routed the English. However,the following year, at the Battle of Falkirk, things did not go so well for him. Although the Scottish rebellion continued, with France, peace was restored in May 1303, when Philip returned Gascony to Edward. That year the Cinque Ports Fleet were sent to Scotland to help the English army against Wallace. The following year, 1304, Philip asked Edward for help to deal with Guy of Dampierre and he sent his old enemy, twenty fully equipped Cinque Ports ships!

The Scottish wars were costing Edward money that he did not have and in consequence, he increased taxes and included the Cinque Ports as a request. Although this was not the first time such a request had been made, it was still against their constitution. The Courts of Brodhull and Guestling met and the Portsmen agreed to pay 2,000 marcs. Hastings paid 700 marcs and the four other Ports 1,300 marcs between them. On 3 May 1305, Wallace was captured at Strathclyde and brought to London where he was publicly executed in the most horrific manner. This was to serve as a warning to other rebels.

On 3 July 1307, Edward died of dysentery and was succeeded by his son, Edward II (1307-1327). On ascending the throne, he was taken by the Cinque Ports Fleet to France where he married Isabella (1295-1358) the only surviving daughter of Philip. They returned on 2 February 1308 and were met by the King’s favourite, Piers Gaveston (c1284-1312), much to the annoyance of Isabella. In June the Portsmen were asked to provide vessels for another war against Scotland but instead, they went to the help of their previous foes, the Bayonnaise, to defeat the Gascons. In August the request was countermanded and an Inquiry took place. It would appear that Edward had not paid for Ship Service in excess of the Chartered days. This appeared to remain a problem for although the King was increasingly calling upon the Portsmens services, this only led to rioting within the town of Dover.

To try and deal with the Ship Service problem instead of paying the outstanding debts, Edward, in 1309, issued an edict forbidding passage from Dover to the Continent of fighting men. This, in effect meant nearly all men and therefore directly weakened Dover’s economy. Recognising that Dover no longer had the protection of the King, the French and Wissant in particular, made the most of the situation by undercutting prices charged for the passage crossing. This became so serious that Portsmen from Dover attacked a Wissant ship. In response, Edward ordered the Lord Warden (1307-1327) Robert de Kendall, to appoint justices to look into what was happening and to settle the grievances. Eventually a fixed timetable for passage ships from both ports was implemented along with an equitable tariff structure. However, piracy continued and within Dover, rioting was becoming the norm. The blame, for all of this, was put on Kendall and he was brought to trial but acquitted.

While this was going on, in 1310, the King had ordered Robert de Kendall and his Deputy Henry de Cobham the younger (c1260-1339), to assess the Cinque Ports, the Antient towns and the incorporated Limbs for taxation. As they did not respect Edward in the same way as his father, they refused. Unlike elsewhere in England, Edward offered the Portsmen a compromise, he allowed them to undertake the assessments to raise the gross sum demanded.

Throughout the medieval period and probably before, a number of specialist industries had developed in Dover, from shipbuilding to rope making and from carpentry to sail making and with them ancillary specialities such as bakeries, builders and so on. These had all been assimilated into the Fellowship of Freemen with obligatory apprenticeship entailments and came under the generalised category of Portsmen. Ship owners had also developed into specialist groups, broadly fishermen and merchants with, at the top end of the first and the bottom of the second, an overlap. Some of the fishermen owned their own small boats, while those at the top of the strata owned a number of similar size boats that they leased out or used themselves. None of these fishing boats were large enough to count for Ship Service although their mariners were. They were also responsible, at that time, for attacking Dutch fishing vessels and stealing their fish.

The merchants, on the other hand, provided passage service across the Channel and carried cargo and passengers along the coast of England and the Continent sometimes running a convey of trading ships into the Mediterranean. Within this group there were a few at the top of the strata that dominated the most lucrative aspects of the industry, notably the passage. When it came to Ship Service, it was the smaller ship owners who were forced to undertake the obligation recruiting fishermen to make up the numbers. It was this aspect that was behind both the piracy and the rioting. So the Justices, in order to try and combat the monopoly of the passage by the wealthier ship owners, recommended that if Dover was to retain the overall monopoly of the passage the town was to accept another Charter. This was drawn up and issued by Edward in 1313, and named the twenty-one Dover ships, with the different owners and stating that each ship was to work in turn to make the Channel passage. Further, each ship owner was to charge exactly the same price that was acceptable to the whole fleet. If a ship owner failed to comply they faced a fine of 100 shillings. Edward, also expressly forbid all Portsmen attacking Dutch vessels and stealing their fish.

Nonetheless, in 1312 the Portsmen were accused of pilfering cargo from Flemish vessels when they were sailing past the Breton Coast. However, little seems to have been done to curb their piratical behaviour. The next year they were called upon to take Edward to France for a length of time greater than obligatory Ship Service. On their return, they were sent to Scotland The Battle of Bannockburn took place on 24 June 1314 and the Portsmen were once again called upon to undertake a military role. However, the King’s handling of the Battle did not impress them, so they left the field and returned to sea. Later that year Robert de Kendall was ordered to account for this and, it would appear, that he gave an acceptable reason. Not long after, Dutch and Flemish merchants were complaining that the Portsmen had returned to piracy. Again, Kendall was held to account and accused of ‘winking’ – ignoring the Portsmen’s piratical activities.

Although cleared, Kendall was directed to persuade the Portsmen to provide ships for the King at their own expense. The hapless Kendall, in March 1316, was ordered to go to every port between Greenwich and Southampton to persuade each of those towns to send as many fully equipped ships as they could, at their own cost, in the King’s service as long as required. Edward’s edict stated that the ‘King wishes to provide ships for the better keeping of the English sea, and for the repulse of certain malefactors who have committed manslaughter and other enormities on the sea upon the men of this realm.’ Similar edicts were issued to every other port between Lynn, in East Anglia and Greenwich and between Southampton and Falmouth, Devon.

The country, at the time, was devastated by a series of bad harvests and as the price of grain reached high prices, starvation was on the increase. This gave the Portsmen another way of making money by stealing grain from the Continent and selling it in England. The Yarmouth men also plundered the Continental ports for the same reason but in 1316,a fleet of Portsmen and the Yarmouth men attacked the same stretch of Continental coast. The Yarmouth men burnt and sank the Cinque Ports ships killing the crews. The Portsmen back in Kent and Sussex, prepared to retaliate but Edward threatened that if they put to sea they would be treated as rebels. For once the Portsmen did as they were bid but Yarmouth was ordered to pay the towns £1,000 compensation.

Albeit, the poor economic state of the country was increasing and along with it, political unrest. The Portsmen returned to their piratical pursuits with vigour and in order to bring them into line, Hugh de Despenser (1286-1326), Edward’s favourite, was appointed Constable and Lord Warden in August 1321. He along with his father were effectively running the country and their rule was later referred to as ‘the Tyranny.’ As the Lord Warden, Despenser took the piratical lead of the Portsmen and like a ‘a sea monster, lying in wait for merchants as they crossed his path‘, they became a frightening force. When Despenser was busy elsewhere in the country, he appointed his friends as Deputies both as Lord Warden and as ‘Pirate King’. Thus, the Portsmen ravaged Channel shipping, the Continental coast, Yarmouth and the coasts of Hampshire, Dorset and Cornwall. The inhabitants there pleaded for the King’s protection against ‘homicides, robberies and ship burning!’ But to no avail.

In France, Charles IV (1322-1328), Edward’s brother-in-law, ascended the throne in 1322. Soon after, he made moves to occupy Aquitaine and the probability of war increased. Charles then allied France with Scotland and in 1324, the Cinque Ports Fleet were paid by Edward to take the English army to Aquitaine as Charles was threatening to retake Gascony. The Portsmen were not asked to fight but to return home and wait instructions. On the way home they attacked towns and shipping, taking the booty back with them. In March 1325, the Portsmen were asked to take Queen Isabella to France where she was instructed to persuade her brother not to invade Gascony and, instead, to accept a peace settlement. The report at the time stated that Isabella was overjoyed to be leaving England and in France did obtain the agreement asked for. However, this required her husband Edward to go to France and pay homage to her brother Charles. Angry, at this affront, the Despensers seized Isabella’s English land holdings and Edward sent his young son, Prince Edward (1312-1377), to persuade his mother to rescind the agreement. Once Isabella had the Prince with her, she joined forces with her lover, the Earl of March, Roger Mortimer (1287-1330).

As an invasion was inevitable, in August 1325, Edward ordered a survey of all English vessels of 50 tons and over to take place in Portsmouth. In September 1326, when Isabella and Mortimer arrived at the river Orwell in Suffolk the crews of the English fleet, which included Cinque Ports vessels, mutinied. This was followed by riots in London and Edward abdicated in January 1327 in favour of his son, Prince Edward. The King was imprisoned and finally ended his days on 22 September 1327 at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, in mysterious circumstances – possibly tortured to death. Hugh Despenser, had been executed on 24 November 1326 but the Portsmen were seen as too valuable an asset to punish. However, ten years later the young King Edward III (1327-1377), in order to keep peace with France, ordered the Portsmen to pay 8,000 marks compensation for their activities against the French under Despenser. Whether they actually contributed all of that sum is unclear but the event marked the start of the decline in the importance of the Cinque Ports Fleet.

When Edward III came to power England was at war with France and one of his first acts was to order the Lord Warden, Bartholomew Burghersh (d1355), to survey the ships of the Cinque Ports and to keep them in repair. At that time, Dover was providing one ship of 140 tons, one of 80 and two of 60 tons to the Fleet. A year later, the order was rescinded as peace with France was declared. This lasted until Philip VI (1338-1350) ascended the French throne. Isabella, Edward’s mother, was the last direct heir to the French throne but as a woman, she was ineligible to rule. Further, Salic Law debarred succession through the female line. Under this law, Philip as a distant cousin of Edward’s, was next in line and Edward objected. Philip’s supporters rallied round him and further, claimed a hereditary claim on Aquitaine. Edward retaliated by declaring himself the rightful king of France and thus started what historians afterwards would call the Hundred Years War (1337 to 1453).

The French attacked Portsmouth and Southampton, Jersey was captured and France controlled the Channel. In dealing with what Edward saw as an impending invasion, he blamed Portsmen for the attacks, saying that it was their duty to guard the sea coast, ‘as the Commons did the land’. He then summoned by proclamation, men of the Cinque Ports to resist the King’s rebels. About this time geological changes to the south east coast were causing the silting up of the Cinque Ports harbours and only Dover and Sandwich were able to match the size of the ships the French were building. The French ships were, on average, about 100 tons and their much larger ones required manning levels of at least sixty-five. Nonetheless, when the King’s exchequer stated that they would meet half the costs, the Cinque Ports did provide a squadron of 21 ships and 9 more came from the Thames. From other sources, Edward’s fleet was eventually increased to 100 ships, all of which were fully equipped and he was ready to do battle.

To ensure that the Portsmen did not use their new ships for piratical reasons, the Lord Warden, William de Clinton, 1st Earl of Huntingdon (c.1304-1354), was told that, ‘as governor of the mariners (he) ought to rule them in all their laws and customs. … Sailors were bound to obey his orders and no master of a ship was to hoist sail or cast anchor before the Admiral. All ships were to keep close to the flagship as possible, and none were to enter port, land any of their crew, leave the fleet or enter an engagement without order.’ This, the Portsmen resented but as part of the Ship Service, in 1339, took Edward and his Army to the Continent. In Ghent, the following February, Edward was officially crowned King of France but Philip retaliated by the French fleet attacking the Cinque Ports of Hastings and Rye. The Portsmen quickly returned from Flanders with vengeance on their minds but by that time the French fleet had sailed off. The Portsmen took revenge by attacking Boulogne, partly burning the town and in the port they sank ships taking 12 sea captains prisoners. Holding a kangaroo court, they accused the captains of attacking English merchant vessels, found them guilty and hung them in the town square.

Philip deployed his navy in the Western Scheldt estuary and in April 1340 proclamations were read in the Cinque Ports towns. The one applicable to Dover stated that persons living within six miles were to withdraw to within the walls. Besides the Castle walls, the town had partly been walled from the late 11th century and by the beginning of the reign of Edward II they probably enclosed much of the town. Edward III‘s fleet met Philip’s fleet outside Sluys on 24 June 1340. The Earl of Huntingdon led 60 Cinque Ports ships. A further 70 ships came from western ports and were commanded by the Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel (c.1306-1376). Edward arrived with a much smaller Royal Fleet of ships, on one of which were Queen Philippa (1314-1369) and the ladies of the court, but he was in overall command. The French had about 190 ships, under three separate commanders. Edward ordered this fleet to position themselves to their best advantage and to work together. He then sent his ships in units of three – two carrying archers and one man-at-arms. From the two ships with the archers, the longbow men, fired the first shots and as they came closer to the French ships, all the archers rained arrows, then the men-at-arms boarded and fierce hand-to-hand fighting took place.

While this was going on, some of the English crewmen clambered aboard the French ships and cut the halliards, thus disabling them. The remaining crewmen stayed on board defending the English ships by attacking boarding Frenchmen and despatching injured ones overboard. The battle had raged for about twelve hours by which time between 20,000 and 30,000 Frenchmen had been killed including two of the three commanders. However, as the French were retreating, one of their ships, James de Depe, turned and attacked one of the Sandwich ships. The Earl of Huntingdon brought the other Cinque Ports ships to the Sandwich ship’s aid and the French ship was captured. On board were four hundred men killed or dying. The English had also suffered a large number of casualties but nothing like the French and they brought the captured ships back to England. These were commandeered by Edward for his navy and in consequence of the Battle, England assumed dominance of the Channel. Shortly after, Edward set up an advisory council that included a delegation from the Cinque Ports.

The following year, Edward sailed from Sandwich leading a fleet of 357 vessels, nineteen of which were from Dover. By 1344 he had about 700 ships in his navy and that year he appointed a Clerk of the King’s ships in charge of the 34 Royal ships. Although the Cinque Ports Fleet was still being called upon in excess of their Ship Service obligation, the towns themselves were coming under increasing attacks from the French. In that year, 1344, Edward decreed that the Dover Portsmen ‘shall give, in the aid of the commonality, out of every ship freighted with horses 2shillings, with foot passengers 12pence, to be collected before leaving the shore, and deposited in a common box by the mayor and jurats.’ The decree finished by stating that this applied in perpetuity for the ‘better supplying of other necessities of the town as they arose.’

Two years later, in July 1346, Edward left England with a force of 15,000 men using the Cinque Ports Fleet to transport them to Caen, Normandy. Once there, the Portsmen instructed the troops on how to quickly sack a town, causing the greatest amount of destruction and loss of life while leaving as much booty to take as possible. The fleet was then instructed to return back to England. This they did, ravaging other French ports en route. From Caen, Edward’s army marched across France and at Crécy, north of the Somme, the English met the much larger French force. Crécy is generally seen as the second great battle of the Hundred Years War and took place on 26 August 1346. The French army was about 50 times greater than the English and well rested. Albeit, Edward made particular use of the long bow with the occasional use of the recently introduced cannon. The French army was decimated.

After Crécy, Edward marched to Calais and on September 1346 he laid siege to the town. He had an army of 35,000 men and a fleet of 710 ships manned by 14,151 men which, besides the King’s ships included squadrons from Bristol, Dartmouth, Dunwich – Suffolk, Fowey – Cornwall, London, Portsmouth, Plymouth and Southampton. From the Cinque Ports:

- Dover furnished 16 ships and 336 men

- Faversham 2 ships and 25 men

- Hastings 5 ships and 96 men,

- Hythe 6 ships and 122 men

- Margate 15 ships and 160 men

- Romney 4 ships and 65 men

- Rye 9 ships and 156 men

- Sandwich 22 ships and 504 men

- Seaford 5 ships and 80 men

- Winchelsea 21 ships and 596 men

- Yarmouth 43 ships and 1,075 men

Although the English planned to adopt the Portsmen’s barbaric tactics, Calais defences were so strong that they were unable to break them down. Instead they went for starvation tactics and the people of Calais held out until 3 August 1347 when six Calais Burghers offered the town up to Edward and asked for clemency for the townsfolk. The King ordered the Burghers to be executed and his troops were ready to go in and do their worst, when Edward’s Queen Philippa threw herself at his feet. She then pleaded with Edward not to commit the atrocities. Instead, she begged him to send the six Calais Burghers and their servants to England as hostages. In return, the people of Calais were to accept English rule. As this gave Edward an English base in France, he accepted this suggestion and Calais was saved.

The Portsmen brought the Burghers and their servants’ back to England, landing at Dover. The Burghers were then taken to the Knights Hospitallers’ main house at Temple Ewell before journeying to London while the servants were taken to the village of Braddon, on the Western Heights. In 1348 the Black Death plague swept England and according to Dover folk-law the Burghers servants brought the petulance to Braddon before it reached the rest of the country. To stop it spreading the villagers of Braddon isolated themselves and thus the village died. Albeit, finding in-roads elsewhere, the disease took its toll throughout the country.

Two years later, on 29 August 1350, an English fleet of 50 ships including many from the Cinque Ports was fighting again. This time at the Battle of Winchelsea or as it was referred to by the Portsmen, the Battle of the L’Espagnols sur Mer. Taking place in the Channel off Winchelsea, the English Fleet was under the combined command of Edward and his eldest son, Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376), better known as the Black Prince. The slightly smaller, though with larger ships, French fleet was under the command of Charles de La Cerda (1327-1354). Although the English won and Edward was given the title ‘Le Roi de la Mer’, his fleet suffered heavy losses. Of the ships the English captured, fourteen came from Spain.

Although Dover lost some ships and men during the Battle, the town at that time was buoyant. Calais had developed into an English market and as Dover had the monopoly of the passage, these were years of great prosperity. However, the Hundred Year Wars continued and in 1355 the Mayors of the Cinque Ports were authorised to press carpenters and others with the necessary skills to build and repair ships. The following year saw the Black Prince bringing John II King of France (1350-1364) as his prisoner, through Sandwich following the Battle of Poitiers of 19 September 1356.

Three years later in 1359 as the Lord Warden (1355-1359) Roger Mortimer, the 2nd Earl of March (1328-1360), was vested with the office of Admiral of the Cinque Ports in perpetuity. Thus every subsequent Lord Warden has held the position. The office was created to prevent complications due to the Cinque Ports being in two counties, Kent and Sussex. Initially, the Cinque Ports Admiralty Court was held in Sandwich, and was designed for local inquests to determine questions of wreck and piracy. However, this conflicted with the role of the Lord Warden within the Cinque Ports chartered rights. The Portsmen complained to Edward that the Earl was listening to pleas beyond the Cinque Ports. The King upheld the Portsmens complaint and forbade the Lord Warden to encroach upon the Portmens chartered privileges.

Albeit, the powers of the Portsmen were already decreasing and as they continued to do so, the powers of the Lord Warden increased. Over time the Lord Warden’s jurisdiction, as Admiral of the Cinque Ports became to include the regulation of trade, especially fishing within the Ports. Also determining all offences at sea, in an area extending from Horse of Willingdon in Sussex to Naze Tower in Suffolk, and seaward to a point 5 miles off Cape Gris-Nez. It was sometimes expedient to hold the Court in other ports than Sandwich but eventually it settled permanently in St James Church, Dover. The increased responsibilities profited the Lord Wardens, as they were entitled to the best anchor and cable from every wreck, shares in goods captured from pirates and payment for fishing licences. Before the end of the century, the post of Lord Warden had become a life appointment.

During these years the French reorganised their fleet into a major force with the aim of regaining the Channel. At the same time Edward’s health went into decline, as did England. Although taxes increased, Edward was forced to increase shipping payments to merchants but for his own contracts, wages were left unpaid including services beyond Cinque Ports’ Ship Service. The French made the most of this and ravaged Winchelsea. The Portsmen were given leave to seek retribution, which they did. Nonetheless, the French continued to gain control of Continental ports and by 1369 controlled the Channel. By 1375 only Calais, Cherbourg, Brest, Bayonne and Bordeaux remained in the hands of the English and the Lord Warden, Ralph Spigurnell was given orders to send the leading men of the Cinque Ports to the King in order to be consulted about the future Navy.

Edward the Black Prince and heir to the throne, after a long and debilitating illness, died in 1376 and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. His father, Edward died on 21 July 1377 and within a week the French attacked Hastings and Rye. They appeared off Dover but did not attack, instead they sailed east then north entering the Thames and burning Gravesend. Towards the end of that year Parliament called upon inland towns as well as ports, to build more ships. Of the Cinque Ports and the Antient Towns, only Dover, Hythe, Romney and Sandwich had functional harbours, the others were becoming land-locked due to silt.

The Black Prince’s 10-year-old son succeeded his grandfather as Richard II (1377-1399), and the war with France continued. To raise money, a poll tax at four pence a head from all lay people over 14, was introduced. This led to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, whose leader, Wat Tyler, came from Kent. The revolt was crushed and what concessions that were initially given, were revoked soon after. In December 1382 a writ was issued for a general press of men in the Cinque Ports following the French military advance into Flanders. This threatened Calais and put a stop to the lucrative English wool trade that through taxation was providing much of the revenue into the Royal coffers. The following year Henry le Despenser (1341–1406), the Bishop of Norwich – grandson of Hugh de Despenser – led an ill trained and ill-equipped expedition into Flanders and was routed by the French.

In April 1386, Charles VI (1380-1422) of France announced a planned invasion of England and assembled an army and fleet at Sluys. Once again a proclamation was issued, stating that persons living within six miles of Dover and other Kent ports should withdraw into the towns for protection. All that summer, along the Scheldt in Flanders, the shipbuilders were busy. In the Cinque Ports, particularly Dover, the shipbuilders were equally active. By September at Sluys, with a navy of 1,200 vessels Charles VI had assembled some 40,000 knights and squires, 50,000 horses and 60,000-foot soldiers. French intelligence stated that Charles intended to land at Dover and the town was instructed, by the Lord Warden (1384-1388), Sir Simon de Burley (c1336-1388), to be fully surrounded by a wall of stone and lime. For this, Dover received ten marks yearly.

Lord Warden Edmund of Langley – Edward Astley window, Connaught Hall design by H W Lonsdale 1892. Dover Museum

At the Castle, 500 men-at-arms and 1,200 archers under the former Lord Warden (1376-1381), Edmund of Langley, the Earl of Cambridge and 1st Duke of York – fourth surviving son of Edward III, were stationed. September came and went but the French invasion did not come. Langley’s intelligence sources said that Charles VI was waiting for John the Duc of Berry (1340-1416) and his men, who finally arrived in October. By the end of that month the weather in the Channel had deteriorated and a succession of westerlies deterred the invasion. However, in 1388, de Burley, the Lord Warden, was charged with the intention of selling the Castle to the French and in May that year, executed for treason.

Between 1394 and 1396 the Cinque Ports provided their full Ship Service for Richard’s passage to both Ireland and Calais, even though only the four functioning ports provided the ships. In November 1396, Richard landed at Dover with his second wife, child bride Isabella of Valois (1389-1409), the eldest daughter of Charles IV of France. The marriage was for diplomatic reasons as it was hoped that it would seal a truce between the two countries. Isabella left France with a large dowry and many expensive gifts that Richard had bought. However, during the rough crossing her dowry, most of the gifts and Richard’s money chest was lost overboard. Dover was obliged to raise £40 as a loan to Richard but was never repaid.

The country’s poor economy strangled by heavy taxation and general discontent brought Richard’s reign to a premature end. In 1399 when he was forced to abdicate to his cousin, Henry Bolingbrook (1367-1413) the Duke of Lancaster and grandson of Edward III. The King was subsequently murdered in Pontefract Castle. His 12-year old widow, Isabella returned to France, through Dover and carried by courtesy of the Portsmen. Henry IV (1399 to 1413), (Henry Bolingbrook) succeeded Richard but by this time the Royal fleet consisted of just four ships, ten years later, only two.

In 1409 Henry Prince of Wales, (later Henry V 1413 -1432) was appointed Lord Warden but due to the increasing ill-health of his father, within a year he was in all practical purposes ruling England. During his tenure as Lord Warden and in the name of his father, Prince Henry made a Treaty with John the Fearless (1371-1419), the Duke of Burgundy (1404-1419), guaranteeing the safety in the Narrow Seas (Channel) for three years. This was achieved by the use of the Cinque Ports Fleet as quasi coastguards. At about the same time an agreement was reached with mariners from Southampton to Thanet with those along the French coast from Honfleur to Hendrenese for a fixed tariff of captured mariners and seamen on their coasts. This was to pay for the prisoners’ board while they were held. Fishing boats, straying into the wrong waters had to be released on payment of 3s 4d and all disputes were to be settled by arbitration.

Thomas FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel (1381-1415), succeeded as Lord Warden in 1413. As the Court of Shepway was still the only external court recognised by the Cinque Ports and their Liberties, it was in the Lord Wardens best interests to foster this. Over time, the Lord Warden became known as the ‘Judge Supreme’ and to suit his convenience the bulk of the work of the Shepway Court was transferred to St James Church in Dover. The first documented case at Dover was heard in 1414 and concerned a breach of contract between Hugh Rys of Sandwich and a Genoese merchant, Thomas Suffye.

After months of negotiation in August 1414, it was agreed that Henry would marry Catherine of Valois (1401-1437), the youngest daughter of the increasingly mad Charles VI of France. This was providing that the crown of France passed to Henry on the death of Charles. However, a feud between the French royal family and the House of Burgundy was causing chaos and anarchy throughout that country and the Treaty of the Narrow Seas broke down. Shortly afterwards, in 1415, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1390-1447), youngest brother of Henry V was appointed Constable and Lord Warden. He retained the position until his death in 1447.

From ancient times, Dover’s harbour was under the eastern cliffs and together with the Bay, made Dover a well favoured port. However, the Eastward Drift that was causing problems to the Cinque Ports west of Dover, and making Dover’s harbour inaccessible at times. The Eastward Drift was also denuding Dover’s beaches such that at high tide the sea came in as far as the present Market Square. To stem the problem the Corporation built a retaining wall from near the corner of Snargate Street and Bench Street along the sea front to the harbour, which they called the Wyke. This created a large quay where passengers and goods could disembark and ship repairs take place. Although the Wyke was initially paid for by the Corporation by wharfage dues. Ship and boat owners – all of whom were Portsmen – had the ancient right of being free of such dues and therefore protested.

The problem was successfully resolved by the Lord Warden – Duke Humphrey who gave the Corporation the fines paid to the Admiralty Court by pilots and ship owners for breaches of regulations. At the same time he gave Dovorians the right of free wharfage in perpetuity. This, the Corporation ignored but an appeal to Henry resulted in a Charter that granted the privilege of free wharfage of Dovorian ships forever. In 2004 this was put to the test by Richard Mahony who operates sea and land tours promoting local tourism. The Dover Harbour Board successfully argued that the privilege had long since fallen into disuse.

At the national level, negotiations over Henry’s claims to the French throne continued until July 1415, when they broke down. With the consent of Parliament he assembled an invasion force at Dover. This consisted of 1,500 ships, including some from the Cinque Ports, and an army of 25,500 men from all over the country and beyond. The Officers of State administered the contingency from the Maison Dieu. On 13 August 1415 the largest force, until World War I (1914-1918), ever to leave Dover departed for France. The convoy arrived at Saint Denise Chef de Caux, at the mouth of the River Seine the following day. They then marched to Harfleur where the town was besieged. The intention had been to go on and take Paris but dysentery was taking a heavy toll on the English force and the siege lasted until 22 September. Henry considered remaining at Harfleur until his men had recovered and further contingencies arrived. On recognising the vulnerability, he decided that his army would be safer to march the 150 miles (240 kilometres) to the English stronghold of Calais.

Henry’s army did not leave Harfleur until 8 October 1415, by which time it numbered about 9,000 and included Portsmen as they decided to stay with Henry. In the meantime, the French Armagnac family who opposed the Burgundian family and Henry’s claim to the French throne, under Charles d’Albret Constable of France, had raised an army of 20,000. The French had reached Rouen and were heading for the River Somme in order to block Henry’s way to Calais. By the time Henry’s men reached the Somme, they were weak, hungry and tired and death due to dysentery was still taking a heavy toll. In order to cross the River, Henry was forced to go south and on 24 October he reached Agincourt, a village three miles northwest of Arras. Henry’s army was reduced to about 5,500 men and the last thing anyone wanted to do was to fight. However, as the French were blocking the way they knew there was no alternative.

d’Albret’s army was considerably larger, fresh, well fed and better equipped. Early in the morning of 25 October, St Crispin’s Day, Henry assembled his men and he deployed them in a single defensive line. Most were dismounted and long-bowmen made up the largest part of the force. Although the French were divided into three large forces, the woodland surrounding the site narrowed their attack. Their first division, that of heavily armoured horsemen were met with a hail of arrows and were unable to manoeuvre. The second division, again mainly consisting of the heavily armoured horsemen, were met with another hail of arrows and besides lacking maneovrebility their way was blocked by the casualties of the first force. Within three hours the French started to withdraw, 6000 of their men lay dead or dying on the battlefield one of which was Charles d’Albret. The English lost about 500 men.

Henry having carried out a victorious campaign sailed from Calais to Dover, where he was hailed as a ‘conquering hero‘ and carried shoulder high through the town. After an equally ecstatic welcome in London, Parliament granted Henry the customs revenues for life, which helped to secure his finances. Then, along with the Cinque Ports Fleet, he returned to Calais in 1416 only to find that the Armagnac dynasty were supporting the Dauphin Charles’ claim to the French throne. On returning to England, Henry revived the navy by ordering larger ships designed to meet changes in naval warfare and many were built in the Cinque Ports. He also modernised his army and in 1417 the Cinque Ports Fleet left Dover escorting Henry back to France. The Portsmen were a small part of a large fleet of ships that Henry‘s army, horses, weapons and sundry baggage required for a military campaign.

On 4 September 1417, Caen in Normandy fell to Henry and on 14 July 1418 he laid siege to Rouen. This was to last until 19 January 1419 during which time John the Duke of Burgundy was seeking a reconciliation with the French Armagnac dynasty. In response, the English government issued a proclamation, on 8 June 1418, calling the inhabitants of the Cinque Ports to arms. However, in September that year the Duke of Burgundy was murdered by a member of the Armagnac faction and was succeeded by his son Philip (1396-1467). In December, Philip aligned himself with Henry against the Armagnac dynasty.

Henry returned to France, by way from Dover, taking with him 24,000 archers and 4,000 choice men-at-arms and on 21 May 1420, at Troyes, signed a Treaty with Charles VI securing his claim to the French throne. On 2 June, Henry married Catherine of Valois and the couple returned, through Dover, to England. On 6 December 1421, Catherine gave birth to their son, also called Henry. However, the Dauphin Charles supported by the Armagnac dynasty refused to accept the Treaty of Troyes and Henry again returned to France, escorted by the Cinque Ports Fleet, in order to secure his claim. On 31 August, during the siege of Meux, Henry fatally succumbed to dysentery and was brought back in a coffin to Dover, once again escorted by the Cinque Ports Fleet. At the port, Henry’s coffin was carried by Cinque Ports Barons while Portsmen with their ceremonial oars reversed and knights with black plumes and lances reversed and many more joined a procession. The sad entourage passed the through the town and along the London Road until it reached London and the warrior King was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. Before he died, Henry appointed his brother Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, his son’s protector.

Most of France was under English rule with John the Duke of Bedford (1389-1435), supported by Philip Duke of Burgundy, as Regent. In October 1424, using the Cinque Ports Fleet, Humphrey invaded Hainaut, which his wife, Jacqueline of Holland (1401-1436) laid claim. As Holland was ruled by the Burgundian family this put the Anglo-Burgundy alliance in jeopardy. Using diplomatic tactics, the Duke of Bedford secured Philip of Burgundy’s allegiance again and Dauphin Charles supporters suffered a string of defeats. That is, until 8 May 1429, when Joan d’Arc triumphantly led the Dauphin’s army of 4,000 into Orléans relieving the city from an English siege. This, together with the coronation of the Dauphin as Charles VII had a tremendous effect on the French morale and a succession of French victories followed. On 24 May 1430 Joan d’Arc was captured by the Burgundian faction at the Battle of Compiegne but one year later she was burnt at the stake by the French. Henry VI of England was crowned Henry II of France on 16 December at Saint-Denise near Paris.

In the wake of the sense of nationalism that was sweeping France, Philip Duke of Burgundy changed his allegiance to supporting Charles VII. On 29 July 1436 French forces under him besieged Calais, but Duke Humphrey, as the Portsmen affectionately referred to him, with the Cinque Ports Fleet attacked and Philip withdrew. Nonetheless, attacks and battles over Henry’s holdings in France raged such that on 14 July 1439 a truce was agreed between England, Burgundy and France. It was agreed that Henry would hold onto lands in France but would not hold the title of King of France. Two years before, Henry’s mother, Catherine of Valois, the sister of Charles VII, died. On her death it was revealed that she had secretly married her lover, Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur – known as Owen Tudor, (c1400-1461). He was a Welsh squire who had attended Henry V at Agincourt and they had three sons and a daughter.

Henry’s English counsel refused to accept the truce and subsequently the battles raged on. By this time William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, (1396-1450), was gaining a great deal of power, particularly at the expense of Duke Humphrey, who was next in line to the throne after Henry. In 1441 Duke Humphrey’s second wife, Eleanor of Cobham (c.1400-1452), was charged with witchcraft and treason. Found guilty, she was imprisoned for life in Peel Castle on the Isle of Man. The Portsmen, always loyal to Duke Humphrey, also came under attack with a number of severe penalties served on the Cinque Ports Barons.

In August 1443, de la Pole landed at Cherbourg with 8,000 men and associated military equipment, with a view to take new lands. This was against the advice of Duke Humphrey as he was using all the resources available to him, including the Cinque Ports Fleet, to retain a hold on Gascony and Normandy. De la Pole, took no notice and further, failed to form a logistical plan on feeding and accommodating his large force or moving equipment. In order to meet these requirements de la Pole levied unlawful taxes on the locals and commandeered their horses and carts. Nonetheless, the exercise still proved to be an expensive fiasco and Duke Humphrey made this known.

Trying to prevent uprisings in occupied France were taking their toll on the English economy and a search for peace became a matter of urgency. Regardless of the Cherbourg fiasco, de la Pole remained a favourite of Henry who promoted him to Lord Chamberlain. In this capacity, de la Pole negotiated a marriage treaty between Henry and Margaret of Anjou (1430-1482), which gained a two-year truce. The couple married on 22 April 1445 and in November 1446, Henry, under Margaret’s influence, gave the Cinque Ports Barons a number of awards to win their trust. Meanwhile, except for his position as Lord Warden, the Portsmens’ beloved Duke Humphrey retired from public life.

In February 1447 de la Pole called a Parliament at Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. On arrival Duke Humphrey was arrested and charged with treason but he died before he could be brought to trial. The next Lord Warden was de la Pole’s supporter, James Fiennes, 1st Baron Saye and Sele (1395-1450) and with the death of Duke Humphrey, this made de la Pole, the most powerful man in England. During the next three years Henry lost nearly all of his possessions in France and holding de la Pole and Saye and Sele responsible he had them arrested. They were imprisoned in the Tower of London and tried for treason. Henry, possibly in a fit of remorse over his favourite plight, commuted de la Pole’s sentence to 5 years exile and he left Ipswich for Burgundy on 30 April 1450. On 2 May, off Dover, his ship was seized and de la Pole was thrown into a rowing boat. There his head was cut off with a rusty sword and his body was dumped on Dover beach. According to local legend, his head was buried in a chalk casket in St Peter’s Church, Dover – it was never found. Lord Saye and Sele was beheaded by a mob in London on 4 July that year.

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1402-1460) succeeded Saye and Sele as Lord Warden, but in March 1454 Henry succumbed to a mental illness. This was not the first time but the appointment of Lord Protector, as was required, led to a power struggle. This led to the civil war known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487). Taking advantage of the turmoil in England, the French attacked the Cinque Ports coast and in 1457 they killed the Mayor of Sandwich, John Drury. To this day, as a mark of respect, the ceremonial dress of the mayor of Sandwich and the mayor of its Limb, Deal, are black robes. The other Cinque Ports mayors wear full length scarlet robes, trimmed with fur.

The Lord Warden, Humphrey Stafford was killed in the Battle of Northampton 10 July 1460 and was replaced as Lord Warden by the Earl of Warwick, Richard Nevill (1428-1471). Neville, was at that time a Yorkist supporter and between 4 March 1461 and 3 October 1470, Edward Duke of York (1442-1483) ruled England as Edward IV. After a dispute with Edward, Nevill switched sides and was instrumental in restoring Henry to the throne. However, he was killed on 14 April 1471 at the Battle of Barnet. On 9 July that year, with the Wars of the Roses still raging, Edward having regained the throne seized the Dover Liberties.

At the time, Yorkist supporter, Sir John Scott (c.1423-1485), was the acting Lord Warden. Edward assumed that Scott and the Portsmen had followed Nevill’s lead and joined the Lancastrian cause. In the Portsmen’s defence, Scott stated that as of ancient right, the Cinque Portsmen were independent in civil wars. Nonetheless, Edward mounted a Commission of Judges to try and punish those responsible for using the Cinque Ports Fleet against him. Thomas Hexstall, the Mayor of Dover and by virtue of office, a Baron of the Cinque Ports, was singled out and arrested. He was put on trial in St James Church. The judges were Nicholas Statham – Baron of the Exchequer, Cardinal Thomas Bouchier (1404-1486), Thomas Dynham, John Fogge, Thomas Echyngham, and William Nottingham. After listening to all the evidence, they pardoned Hexstall who went on to be the Mayor of Dover six more times!

Henry VI was imprisoned in the Tower of London where he died on 21 May 1471. By that time Edward had appointed the William fitz-Alan the 16th Earl of Arundel (1417-1487) Lord Warden. From then on the Portsmens political influence was superseded by the Lord Wardens and this was on the ascendancy. Nonetheless, on 26 May 1475 Edward called out the Cinque Ports Fleet to wait off Sandwich. On the 26 June they were ordered to take his army from there to Calais, from where Edward proposed to launch an invasion. This was to claim the throne of France especially as the French King, Louis XI (1461-1483), had backed the Lancastrian cause during the Wars of the Roses. Edward expected a military support from Charles Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477) but although the Duke turned up, he only brought his body guards. Edward was therefore forced to compromise and agreed to leave France on payment of £15,000 and an annual pension of £10,000 a year for 7 years. Also for Louis’s son, Charles (1470-1498), to marry his daughter Elizabeth of York (1466-1503).

On the death of Edward, Richard Duke of Gloucester (1452-1485) claimed the throne as Richard III (1483-1485). The Lord Warden, Earl of Arundel attended his coronation. It was expected the Cinque Ports Barons would do the same and also carry the coronation canopy. Instead, the Courts of Brodhill and Guestling was convened and after a discussion the Cinque Ports Barons issued the order ‘No precept from Dover Castle to be obeyed.’ Whether any did attend is unclear but following the coronation, Richard, showed particular favour to Dover by imposing on persons, horses, sheep, cattle and merchandise carried between Dover and Calais, a tax to enable the town to build a new sea wall. Two years later on 22 August 1485, Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field – the last battle of the civil war. The victor was Henry Tudor, 2nd Earl of Richmond (1457-1509), whose paternal grandparents were Catherine of Valois and Owen Tudor. Henry married Elizabeth of York and when he was crowned Henry VII (1485-1509) the Earl of Arundel attended. He held the golden coronation canopy over Henry’s head along with the Cinque Ports Barons!

Dover harbour c1540 following the completion of Sir John Thompson’s new harbour at the western side of the Bay

About this time there was a massive cliff fall that rendered Dover’s Eastbrook harbour useless. As all but Sandwich of the other Cinque Ports harbours had or were succumbing to the Eastward Drift, Henry transferred the cross-Channel traffic to Sandwich. He then issued an edict stating that goods were only to be carried in English ships. John Clark, the Master of the Maison Dieu, on behalf of Dover, successfully petitioned Henry for a grant to build a small harbour on the western side of Dover Bay. When this was granted, it would seem that the other Cinque Ports did the same. In response, Henry made a grant in recognition of the past services of the Ports, ‘for the better enabling the ports in their ordinary charges at sea and maintenance of shipping, and not in particular for the furnishing out of shipping upon extraordinary occasions of state.’

The Cinque Ports and their ships had become the target of pirate attacks and in 1487, Henry, for a fee, agreed to provide three guard ships. Five years later, in November 1492, the Portsmen took part of Henry’s army to Calais from Sandwich. Although preparations for war were being made the expedition ended amicably. The following year Henry appointed his younger son, also called Henry (1491-1547), the Lord Warden. Prince Arthur (born 1486) as the elder son, was the heir to the throne until he died in 1505. Even though elevated to that of heir, Prince Henry retained the office as Lord Warden until he ascended the throne in 1509 as Henry VIII (1509-1547).

The Cinque Ports Fleet maintained their ancient obligations as best they could during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547), taking his army from Sandwich to Calais in 1513 and from Dover to Calais in 1520, 1544 and 1545. Having six ships of one hundred and sixty tons each, the Portsmen remained at sea for five months at their own expense in order to show that they were still viable. Indeed, in 1588, the Cinque Ports Fleet set sail from Sandwich, to confront the Spanish Armada. Each of the six ships had one pinnace of thirty tons, in attendance and one of ships, said to have belonged to Dover, acted as decoy leading one the Spanish galleons onto a treacherous Goodwin Sandbank. There, the beleaguered galleon was set upon by the other Cinque Ports ships, her crew killed and the ship completely destroyed. This was the last action of the Cinque Ports Fleet but in 1590, the Lord Warden, Sir William Brooke, 10th Baron Cobham (1527-1597) officially acknowledged the existence of the Courts of Brodhull and Guestling.

At the beginning of the reign of Charles I (1625-1649), the Cinque Ports fitted out two large ships which served for two months and cost them £1,800. In 1663 the Cinque Ports bailiffs made their final appearance at the Yarmouth Herring Fair but the office of Lord Warden continued to go from strength to strength. In 1673, the Lord Warden was given the right to raise a militia within the liberties of the Cinque Ports but during the War of American Independence (1775–1783) this was superseded by the Cinque Ports’ Volunteers Regiment (see Western Heights part I). The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) brought renewed threats from the Continent, and the Lord Warden raised several volunteer horse and foot soldiers in the ancient name of Ship Service and were named the Cinque Ports’ Fencibles. Shipbuilding remained one of the mainstays of the Cinque Ports with fishing one of the main industries. The passage from England to the Continent that had been given to Sandwich was returned to Dover and became a major industry that the port still retains.

Baron of the Cinque Ports Costume worn by Wollaston Knocker at the coronation of Edward VII 1902. Dover Library

With the passing of time, most of the ancient rights and privileges that the Portsmen had enjoyed ceased to exist. The individual Courts of Brodhull – renamed Brotherhood – and Guestling united in the 19th Century and are these days generally referred to as the Confederation. The Speaker is drawn from the Mayors of the members of the Confederation, in rotation and on 21 May each year. The Confederation, with all the traditions of former times, meets to witness the transfer of the Speakership. Each port and corporate member of the Cinque Ports are expected to send a deputation even though the business transacted is nominal. The title, Baron of the Cinque Ports devolved to the Mayors and these days the title only applies to Mayors on the accession of a monarch to the throne.

The office of Admiral of the Cinque Ports was extended to cover the whole of the English fleet and gave the Lord Wardens the right of exercising jurisdiction in Admiralty cases according to maritime law. The Admiralty jurisdiction continues to this day, being confirmed by the Municipal Corporations Act of 1883. Within its defined limits it is concurrent and equal to that administered by the Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice. The last full sitting of this court was in 1914, however the Lord Warden still appoints the Judge Official and Commissary. Albeit, like the Court of Chancery the Admiralty Court, in reality, survives in name only.

The importance of the Shepway Court to the Lord Wardens decreased along with the importance of the Portsmen. These days, the only real purpose of the Court of Shepway is the installation of the Lord Warden. Once installed, the Lord Warden can exercise the right of presiding over it. In August 1923, during the Wardenship of William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp (1872-1938), a Cross was erected on the site where it is believed the original Court of Shepway was held.

Dover Councillors as Barons of the Cinque Ports at the Installation of Lord Boyce as Lord Warden April 2005. Dover Mercury

Lord Warden’s role was extended in 1606 to that of presiding over the Dover Harbour Commission, later Dover Harbour Board. This lasted until 1905 when George, the Prince of Wales was appointed – later George V (1910-1936). A special Act of Parliament relieved him and subsequent Lord Wardens of serving on Dover Harbour Board. In 1708, Walmer Castle was made the official residence of the Lord Warden and this remains so today. The substantial salary that the Lord Wardens once received ceased in 1828 but the inauguration ceremony was given a new lease of life with the appointment of Lord Palmerston as Lord Warden in 1860. At the same time, Dover became the Head Port. In 1978 Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, became the first female Lord Warden and not only proved to be a great favourite with the folk who live in Cinque Ports, she resurrected its historic significance. The Present Lord Warden is Admiral of the Fleet Michael Cecil Boyce, Baron Boyce, who was appointed on 10 December 2004 and installed on 12 April 2005.

Sadly, the twin institutions of the Cinque Ports and the Lord Warden have, over the last few years, become increasingly remote and elitist. Such that following the publication of this story a considerable number of people, many of whom live in the Dover area, were surprised to read that the twin institutions still existed.

- Presented: 29 February 2016