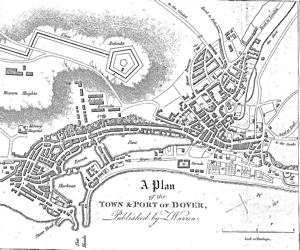

Dover shipbuilding can be traced back to the Bronze Age (2100BC-700BC) – see Shipbuilding Part I. The demand for ships produced in the town had oscillated over the centuries reaching new heights in the 18th century. As the century progressed, the town had seen the sailing ships built on its beaches earning the accolade the ‘Pride of Europe’ see Shipbuilding part II. They were mainly built out of locally grown oak, Quercus Robur, in sustained forests that surrounded the town at Alkham, Elham, Lydden, Lyminge, Temple Ewell and Whitfield. The ships were ordered and bought by passage and cargo operators as well as merchants and could be easily adapted as fighting machines in times of hostilities. At such times, regardless that the Royal dockyards of Portsmouth (founded 1496) Woolwich (founded 1513) and Chatham (founded 1547) provided much of the Royal Navy needs, they too bought Dover built ships. Particularly Brigs, a two masted vessel with square sails on each mast for power, and fore-and-aft staysails for manoeuvrability along with jibs and a spanker.

Napoleonic Wars part one 1793 to 1802

On 1 February 1793, France declared war on Britain and the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) began and this brought increased prosperity to Dover. Corn mills supplied flour for the troops billeted in the town and naval ships in the harbour, the number and variety of retail shops along with family industries increased. Even Dover’s dark industry of smuggling continued to thrive adding to the town’s wealth and the amount of black market goods that were sold by street sellers and available in the town’s shops!

However the Wars put a great deal of strain on the British economy as the country’s defence forces and the constant attacks on both imports and exports had the effect of increasing prices. Between 1793 and 1796, the increase in the government’s deficit abroad amounted to £36,439,269 with excise and customs duties its main source of income. This was of a similar magnitude to the deficit that had started the chain of events culminating in the French Revolution (1789-1799). Because of the influx of both the military and the naval forces into the town, Dover’s economy boomed but this was not reflected elsewhere in the country. Adding to Dover’s wealth, the Royal Navy ordered new ships and hired existing ships as well as issuing Letters of Marque were issued to existing ship owners giving a rise to the demand for more ships to undertake privateering.

Privateer Bury Air from Dublin bound to London taken by hired armed cutter Dover by Patrick Donavan. Michael Sharp

The Dover, an armed cutter owned by Thomas Spice and captained by William Sharp was hired by the Board of Admiralty and stationed at Plymouth. In a letter dated 02 November 1796, belonging to Michael Sharp, written to Evan Nepean (1752-1822) Secretary to the Board of Admiralty 1795-1804 by Captain Sharp, the captain gives an account of his duties writing: Sir, I am to acquaint you that in the execution of their Lordships orders I fell in with NNW of Dodman (Head) a French privateer La Marie Anne with six guns and 37 men from Brest (Brittany) 4 days and had taken the Bury Air 130tons berthen laden with provisions from Dublin bound to London. I have the satisfaction to inform you that I have taken the above vessel and arrived at this Port (Plymouth) with the prize.

I am your obedient servant

William Sharp

Fight between the Ladd shipyard built Enterprise and the French brig Flambeau summer 1800. Wikimedia

Dover Diarist, Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819), who lived on Townwall Street, gives numerous accounts of confrontations between Dover and French privateers during this time. Another contemporary account of privateering in the Channel off Dover tells us that these conflicts usually took place in the late evening and provided entertainment for the locals. ‘It was curios on these occasions, to see men, women and children, running in multitudes and as eager to witness these conflicts, as they would have been to view some harmless amusement. None seem conscious of fear; but the field pieces, firing unexpectedly before the crowd, would sometimes cause them to scamper behind buildings.‘ While Dover’s Latham Bank, run by Sam Latham (1752-1834) loaned money to mariners to buy their own privateers. He wrote, ‘We always charge 2½% commission in advance of money to Captains of ships. Or an amount in prizes. We furnished the Duke of Montrose with an auctioneer here, regulated and charged accordingly.’

King George I cross Channel sailing packet the 70-ton sloop owned by John Minet Fector. Painting by Gordon Ellis. A model can be seen at Dover Museum.

At this time, the senior member of Dover’s other bank was John Minet Fector (1754-1821), who had already earned the reputation as East Kent’s Godfather of smuggling. He was not only highly respected, he was loyal to those who worked for him. This was shown when the captain of the Prince of Wales, one of the Fector cross-Channel packets, was found carrying a substantial amount of contraband. Fector stood bail for a ‘considerable sum’ and although the smuggled cargo was impounded, no charges were brought against the captain. Nonetheless, there was concern over Fector’s alleged smuggling activities, in particular, expressed by Thomas Mantell (1751–1831), who was six times Mayor between 1795 and 1824. Mantell led a crusade against smuggling and in April 1799, Fector was accused of ‘aiding the enemy‘ by smuggling gold to France in return for wine and brandy. Although the evidence against him was strong, not only due to the rumours surrounding his cross Channel packet King George I but because of Fector’s own frequent crossings to Revolutionary France in the King George I. For reasons unclear at the time the case was dropped. It later transpired that Fector had been heavily involved in bringing French aristocrats, who potentially faced the guillotine, to England.

Plans of profile and decks of the Zephyr, built as a packet ship by the King shipyard. National Maritime Museum Greenwich; Admiralty Collection

At the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars, the King shipyard, on Dover beach, was the only commercial ship builder in the country that the Royal Navy ordered or/and bought non-custom built ships. The shipyard had completed the gunbrig Piercer in 1794 while the 243ton brig Zephyr, that was being built as a packet ship, was purchased during construction the following year. However, they did charter (hire) ships, including those built by other Dover ship builders. The Nancy, a 46tons 6gun armed cutter with Master Henry Watson and 19crew was chartered to carry despatches. She had been a privateer during the American War of Independence (1775-1783) under Captain Edward Norwood and was then owned by William Mellish and Captain Norwood. In 1794 she was taking despatches to Admiral Samuel Hood (1724-1816) at Hyères Bay, near Toulon, South of France, but was captured by four French frigates. When the Peace of Amiens was declared in 1802, she was released and returned to Dover and was then bought by William Crow. He changed her name to Francis and between 1805 and 1806 she was chartered by the Admiralty to carry despatches again.

When the Zephyr was purchased in February 1795, she carried 76 men 16x6pounders and 10x4pounders and cost £2,660. Registered in May that year, the Zephyr had a glittering career, in January 1797, she took 12gun privateer La Reflechie while on a passage to the West Indies. Later that year she took the 4gun La Vengeur des Francais, the 6-gun La Legere, the 2-gun Le Va-Tout, the 8-gun privateer L’Espoir and with the Victorieus the 6-gun privateer La Couleuvre. Other Dover built ships based at the port were also involved in confrontations, as French privateers were constantly attacking shipping in the Channel. In 1793 the Cumberland, under the command of Matthew King had survived a fight with a French privateer while bringing much needed wheat over from Belgium. Other ships that had ferocious battles in the Channel at this time included the 72ton Favourite and the Union, both against French privateers.

Battle of Copenhagen – 02.04.1801 the Harpy next ship to the bottom. Sir William Laird Clowes (1856-1905).

1796 saw the launch of the 314ton Diligence class brig Harpy and the 192ton brig-rigged cutter Rambler at the King shipyard, the latter purchased while being built. The Harpy was launched in February 1796 and cost £3,683. She was commissioned in April under the command of Dovorian, Henry Bazely (1768-1824) and with a crew of 120men, she set sail for the Downs. There she took French privateers Le Cotentin in February 1797 and L’Esperance June 1797. She was part of Rear Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham’s (1762-1820) squadron at Ostend on 8 May 1798 to destroy the sluice gates of the Bruge canal. February 1800 saw her in action with the Fairy against 46-gun Le Pallas and in April 1801, the Harpy was part of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson’s (1758-1805) fleet that defeated the Danish Fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen (2 April 1801). It was in this battle that Nelson, having been signalled to withdraw his fleet, is said to have put the telescope to his blind eye and pressed on with the attack, saying that he did not see the signal.

The result of the battle was that Denmark ceased being part of ‘The armed neutrality of the North,’ which allowed Russian grain to be brought through the Baltic thus helping to combat shortages in Britain and strengthening the blockade against the French. The French, for their part, retaliated by blockading British ports and attacking more Channel shipping. Following the Battle, the Harpy was paid off but was recommissioned and involved in many of these hostilities in the Channel. This included the attack on invasion craft at Boulogne in July 1804, gunboats off Vimereux (Wimeroux) in August that year and invasion crafts near Cap Griz Nez, April 1805.

Nelson fails against the flotilla near Boulogne 15.08.1801 Louis-Philippe Crepin (1772 – 1851) Wikimedia

The King shipyard launched the 18-gun sloop Echo, designed by Sir John Henslow (1730-1815), in 1797 at a cost of £4,010. She was fitted out at Deptford having sailed there using a temporary, or more correctly, a jury mast and the final cost, including fittings was £9,014. She was commissioned in October 1797 under Commander Graham Hamond and with a crew of 121 men the Echo sailed for the North Sea. On 14 February 1797, 15 ships of the British fleet, under Sir John Jervis (1735-1823), attacked 23 battleships of the Spanish fleet at the Battle of St Vincent off the south west coast of Portugal. Six months later, on 1 August, 13 French battle ships were attacked while at anchor by 14 battleships under Nelson at Abu Qir bay, near Alexandria, Egypt. Known as the Battle of the Nile, after a fierce fight all but two of the French ships were captured or destroyed.

Albeit, on 22 July 1801, it was said that soldiers from the Castle reported that on the hills around Boulogne they could see Napoleon’s army getting ready for invasion. In the harbour ships were being prepared to bring an army across the Channel. Within five days a convoy, under the command of Nelson assembled in the Downs off Deal. At 22.30hrs on the night of 15 August ‘8 flat boats 8inch howitzers with a Lieutenant in each and 14 men and artillerymen … and 6 flats with 24 pounder carronades with a Lieutenant in each, seamen and 8 marines … under the command of four captains,’ crept into Boulogne harbour. Unfortunately, the boats did not arrive together and the first ones roused the French who quickly took to their boats. They defeated the British flotilla such that of the men who set out, 44 were killed and 128 were wounded. Not long after, the Echo sailed for the West Indies and was based at the Jamaica station. She was laid up in October 1806 and sold in May 1809.

The War brought prosperity to Dover and one of the many beneficiaries were Dover’s corn mills. They supplied the troops billeted in the town and naval ships in the harbour with flour and the Maison Dieu was used as a giant bake house. The Royal Navy had built Stembrook mill in 1792 and it was rebuilt and enlarged in 1799 and again in 1813. Thomas Horne (1754-1824) rebuilt the Town Mill in 1802 and his corn mill at Charlton was in full swing. In 1812, the Pilcher family rebuilt the Crabble corn mill we see today and they also rebuilt Temple Ewell and Kearsney Court mills. Some of the materials for the buildings were brought to Dover by ship as was the corn, mainly from Belgium, used in the milling industry. This increased the demand for local ships and in turn increased the number of ships being built by Dover shipbuilders.

Head of the long established shipbuilding yard, Henry Ladd junior (1755-1801) died in 1801 leaving the shipyard, which would start making a profit when the finished ships were paid for, to be run by his brother Luke (b1758). Henry’s sons Thomas (1781-1851) and William (b1783) were preparing to be apprenticed as shipwright/boat builders with their uncle but by October 1801, moves were being made to sign a peace treaty between Britain and France. This resulted in the Peace Treaty of Amiens of 27 March 1802.

Castle Hill House where the Mayor George Stringer held a grand ball to celebrate the Peace Treaty of Amiens of 27 March 1802. Alan Sencicle

In the Castle a French prisoner was making a model of the French Man O’War the Cesar out of the bones left over from his food rations. With the signing of the Peace Treaty he voluntarily remained a prisoner so he could finish the model! On the evening the Peace Treaty was signed, Mayor George Stringer (1769-1839) organised a Grand Ball at his home, Castle Hill House, but many in Dover, including Luke Ladd, were hoping that Peace would not last. While of those who attended the Ball and were privy to the terms of the Treaty, did not expect it to last as the terms meant that the French could exclude the British from trading with ports that had French ties.

Nonetheless, the Dover garrison was reduced from 10,000 men to just a few hundred and the major turn down in the economy was rapidly leading to the neglected harbour entrance becoming increasingly blocked with shingle. Local traders were drifting into bankruptcy and although 40 shipyards were recorded to exist on Dover beach, the rapid economic downturn meant that many of these premises were desolate.

Dover’s most successful shipyard, owned by the King family was suffering badly as they had specialised in providing ships for the Royal Navy. Not only was there a fall off of orders, ships that had been ordered but not paid for, were no longer required and left at the shipyard without a buyer. Whether it was the situation that caused Thomas Jones King’s incapacity is difficult to know but at about this time, either through an accident or illness, he was permanently moved to a sanatorium. John King took over the running of the business but the completed brigs Gannet and Hunter stood as stark reminders that they had no takers and John King had to lay off all his skilled and unskilled men.

Round Down Cliff showing the entrance to the smuggling storage cave called the Coining House. Alan Sencicle

Many of Dover’s out of work mariners turned to the age-old occupation of smuggling, with those shipbuilders still in existence adapting ships to hide contraband. This was the only aspect of the town’s economy that was improving. Indeed, when Kent historian, Edward Hasted (1732-1812) was writing, circa 1798, he noted that in the middle of Round Down cliff, to the west of Dover, ‘are two large square rooms cut out of chalk’. ‘One‘, he wrote, ‘is within the other, they are called the Coining House, and have a very difficult way to come at them, the cliff here being upwards of four hundred feet high.‘ It was said that the Coining House caves, in the Parish of Hougham, were used to store smuggled goods and the parish church of St Laurence Church was one of Dover’s main clearing houses of contraband. The vicar of Church Hougham was Thomas Tournay (d1795) and he was also the rector of the mariners’ St James Church, close to Dover’s Castle cliffs and an area known for the storage of contraband. On his death, Tournay’s son, William (d1833), was appointed Church Hougham’s vicar and it was still generally acknowledged that St Laurence Church was a clearing centre. Albeit, it was not until major restoration of St Laurence Church in 1866, that this was proved. Evidence of smuggled contraband was found hidden among the Church rafters, within the pulpit, the font and numerous other places!

Napoleonic Wars part two 1802 to 1815

The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports,William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), whose niece, Lady Hester Stanhope, (1776-1839) acting as deputy, set up the Cinque Ports Fencibles or Volunteers. The 1805 painting shows, the Lord Warden in his full dress uniform. Dover Museum

Hint of possible end to the peace first arrived in Dover one day in early March 1803, when two officials from the Admiralty arrived at the King shipyard. They ordered thirteen brig-sloops of the 1795 Merlin design and brig-sloops built to Royal Navy’s surveyor, Sir William Rule’s Cruizer Class design of 1797! Within days, the possibility of war became a reality and with it the much-needed demand. By the end of March 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte announced that Britain had violated the Peace of Amiens Treaty and subsequently occupied Switzerland as well as closing the Dutch Ports to British trade. On 17 May, Britain declared war on France, the government remobilized the Navy and reintroduced the Letters of Marque. Many of the shipbuilders fitted out cross-Channel packet boats as fighting ships. However, in order to raise more money to finance the War, the government re-introduced Income Tax that had been set up and abolished the year before. To recruit more men to the armed forces, they passed the Army Reserve Act to encourage the enlistment of volunteers. In Dover Lady Hester Stanhope, (1776-1839), acting as deputy on behalf of her uncle, the Lord Warden William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), set up the Cinque Ports Fencibles or Volunteers.

The Army Reserve Act also enabled the setting up of the Impress Service or Press Gangs. Made up of both naval officers and men, they went into taverns or even entered homes uninvited to enlist men. At Dover, they preferred to take seamen from merchant ships that stopped at the port. Or alternatively, seamen ‘recruited’ under the 1805 Prevention of Smuggling Act, which enabled any physically fit seaman found on vessels seized, regardless of whether contraband was found, to be impressed into the Royal Navy for five years. They also duped men from the maritime Pier District of Dover and shipbuilders along with those involved in the ancillary ship building trade were also coerced. At Dover, while awaiting transportation, all of these men were held in the town goal and in 1806 the Riot Act was read when a mob tried to release them. When control was regained, the Mayor, Robert Hunt (1754-1808) managed to commit the angry seamen and reluctant volunteers and sent them under escort to Newgate prison in London. It was later reported that at the time of the Battle of Trafalgar – 21 October 1805 – over half the Royal Navy’s 120,000 sailors were pressed men.

At least two of Dover built and owned ships were hired by the Royal Navy to be used by the Impress Service, which at this time was under the command of Lord William Allen Proby (1779-1804). One such ship was the 68ton with 6x3lb carriage guns, Minerva that was leased to the Service between 1803-1804 at £2,090 per annum by businessman and banker, Henshaw Latham (1782-1846). The second ship was the 48ton x 4gun Ant, owned by businessman Richard Mowll (1763-1811) and was hired for pressing between 1803-1810. Unlike ships commandeered by the Royal Navy, neither Latham nor Mowll were expected to provide crews, instead, the base crew were the pressed men augmented by seamen ‘recruited’ by the press gangs or through the Prevention of Smuggling Act.

The renewal of hostilities for Dover meant an influx of about 20,000 soldiers into the town and at the same there was an increase in the demand for Dover built ships. These were for both transportation of the soldiers and also as back-up vessels in the war zones. Then on 18 May 1804 Napoleon declared himself Emperor and the fear of invasion was very real. By 9 August, more than 100,000 seasoned French troops had amassed on the hills outside Boulogne, while in the French harbour there were 2,000 landing craft at the ready. The Cinque Ports Volunteers set up a chain of semaphores from Dover to London, so messages could be passed to George III (1760-1820) should the invasion force arrive. Queen Charlotte (1744-1818) was sent to Worcester with the Crown jewels for safety. The Volunteers then stood to arms for four successive nights along the shore waiting to resist the invasion. For the remainder of the wars, they manned the defence of the coast and built a defensive wall at St Margaret’s Bay, which can still be seen.

The Grand Shaft triple stairway built in the Napoleonic Wars to get soldiers quickly down to the harbour from the barracks on the Western Heights. Dover Museum

In Dover, a massive defence programme was also started on Western Heights, with the Citadel at the centre. The complex also included the Drop Redoubt Fort, batteries, deep moats, barracks, a military hospital and the Grand Shaft triple stairway to get soldiers quickly down to the harbour – and can still be seen. Across the valley, at the Castle, the Mote Bulwark and the Guilford Shaft were built to link the Castle with the shore. On the seaward side of Townwall Street a defensive canal was dug – all traces of which have long gone. Military building together with victualling meant that local trade boomed in the town as never before and bricks that were initially brought in by sea from Ipswich but at a cost of £3.12s 6d per thousand, galvanised Dovorians into manufacturing them. Dover’s first recorded brickfield was started at Dodd’s Lane, off Crabble Hill, in 1808.

The defence programme, as expected, included shipbuilding but there was a shortage of experienced shipwrights and ancillary trades brought about by the over zealous Impressing regime of Dover men. The Admiralty, however, particularly wanted Cutters, Brigs and Sloops, to accompany the Royal Navy fighting fleets or to carry despatches. Word went out and skilled men came to the town but due to the archaic town’s Freemen laws, they were not allowed to set up workshops on their own account. Nonetheless, by the end of 1804 there were some 40 shipyards recorded on Shakespeare Beach, owned by local Freemen. These included, the Cullin, Divine, Duke, Gilbee, Gravener, Hedgecock, Hubbard, Johnson, Kemp, Kennett, King, Large, Pascall, Pilcher, Walker and Worthington families.

Espoir sloop of 14guns with the Liguria of 44guns by Nicholas Pocock Published by Bunney & Gold 1801 Wikimedia

The King shipyard had already accepted four orders from the Royal Navy and managed to employ sufficient men to work on the first, the 383ton Scorpion, launched in October 1803. She was fitted and coppered at Sheerness and was Commissioned under Commander George Hardinge in November 1803 for the Channel and the Downs. The Scorion was involved in several confrontations and in 1807 sailed for the Leeward Islands, where again she had several successful confrontations. She was laid up at Sheerness in July 1813.

The shipyard then built the 385ton, 14gun, sloop Espoir launched in September 1804 and commissioned the following month. After an active career she was paid off October 1816 and laid up in Portsmouth April 1821. While the Espoir was being built, the King shipyard had managed to recruit a full complement of workers and started on the 385ton 18gun sloop, Moselle. She was launched in October 1804, commissioned in December and had an eventful career. Most notably at Cadiz on 27 February 1806 (see below), following the Napoleonic Wars, she was sold at Deptford in December 1815. The Ladd shipyard, just managed to remain viable such that by 1805 Luke Ladd signed his nephew, Thomas as an apprentice and the following year his brother, William.

A cutter, frigate and an Indiaman with other ships all of which are typical of the ships that had been produced by the Dover shipyards. Wikimedia

To save money, the Admiralty decided to augment the Royal Navy’s specially commissioned ships and ships awaiting customers in shipyards. To this end they chartered vessels, with the numbers steadily increasing during the following years, each ship being subject to a contract. This was usually for a period of 12months with possible extensions with the contract between the owners and three commissioners from the Admiralty. The owners were expected to fit the ships out with the crew, guns, ammunition and stores and to strictly comply with the contract terms. If there was any deficiency in any of the stipulations, such as the number of qualified officers, the number of the crew or the amount of supplies etc., deductions were made accordingly. This could mean that the owner could make a loss on the transaction, as it was often difficult finding and retaining crews. Further, the ship might be captured or lost at sea, in either case the contract came to an abrupt end.

In 1803 -1804 the following Dover shipyard built ships were hired by the Admiralty – owners name given if different from the shipyard:

From Peter Becker (1764-1842) & Richard Jell’s (1762-1847) shipyard came the 120tons Ann – a brig with 39 crew and carrying 10 carronades. She was chartered from 1804 to 1809.

From Samuel Collett and Messr Thomsett’s yard came the Venus, a 50ton ship originally owned by John Minet Fector (1754-1821) and armed with 6x3lb carriage guns. She was hired by the Admiralty between 1803 and 1805 for £2113 a year but was captured by a French Squadron in the Mediterranean in January 1805, so Collett and Thomsett lost heavily on the deal.

Richard Emmerson (1749-1817) of Sandwich owned the 84ton Hope, which carried 8x12lb carronades. She had a crew of 30 and was chartered in 1803-1805 for £2,605 per annum.

William Crow, William Pepper and Captain John Blake, owned the 124ton Nile. She was chartered between 1804 and 1806 for £4,576 year and carried 18x6lb carriage guns.

John Gilbee (1742-1815), by this time the single owner of the former Gilbee and Farley shipyard, rented out the 44ton Alert II, the smaller of two Dover ships of that name, with 20 crew and carrying 6x12lb carronades between 1804-1813.

Ship owner, packet contractor and banker, John Minet Fector rented to the Admiralty a number of Dover built ships including the larger, 78ton Active II with a crew of 27 under the ship’s Master, John Middleton (1751-1835). She carried 8x4lb carriage guns and was chartered between 1803-1814 for £2,360 a year. Fector’s 76tons 8 guns and 3masted cutter with 25 crew, Swift I was chartered in 1803 for an expected prolonged usage. She had been a privateer under different owners during the American War of Independence and was a sturdy ship, but was taken by the French in the Mediterranean in April 1804. The 100-ton Swift II with 8x12lb carronades and 30 crew was chartered 1803-1806 for £2,732 per year. The 75 ton Queen Charlotte I carrying 8x4lb carronades and 25 crew, jointly owned by Fector, Collett and Thomsett was chartered from 1803 to 1814 for £2,211 a year. While, the 60ton Queen Charlotte II with a crew of 25 under the ship’s Master, James Thomas and was chartered between 1803-1812.

Other Dover built ships Fector chartered to the Admiralty included the 50ton Athens with 24 crew and carrying 10x4lb carriage guns for £1,695 a year. The 56ton Dart with 6guns and 21 crew; 60ton Dolly with 22 crew, which Fector jointly owned with John King (b1769) and the 160ton Nymph with 10x4lb carriage guns, 23 crew under Master James Michael Boxer (1758-1840) were chartered between 1803 and 1804. Jointly with Collett, Fector owned the 79ton Phoenix with 8guns and 25 crew, he also owned the 124ton cutter Hawk with 40 crew under the Master James Cullen. Normally, he used her as a cargo vessel to Yarmouth, the Channel Islands, Belfast and Lough but chartered her to the Admiralty between 1803-1805 for £3,569 a year.

The Fector owned 128-ton cutter King George II with a hull designed to offer the minimum resistance in the water. She was chartered between 1803 and 1804, renamed Georgiana. In September 1804, she was grounded in the mouth of the river Seine on the ebb tide and set on fire by the crew before escaping from the French. Although, notice was given that the Georgiana was destroyed, in fact Fector and the crew rescued her! They brought her back to Dover where she was repaired and refitted by the King shipyard. On taking her original name she resumed service in Fector’s fleet.

The King shipyard built and rented a number of ships to the Admiralty at this time, including the 129ton former privateer Drake with 43 crew under Captain Matthew King (1759-1832), with 12 x 12& 6lb carriage guns. Chartered between 1804 and 1805, the Drake was jointly owned by John King (born 1769), Thomas King (1739-1815), Nicholas Ladd and Nicholas Steriker (1767-1830). The Lord Nelson I renamed Frederick in 1804 – 68tons 6x4lb carriage guns was chartered between 1803-1805. However, due to shortage of finances, following the Peace of Amiens, the King shipyard could not afford to have her coppered. When this was realised by the Admiralty, the Frederick was discharged. It was also stated that because of her size and deficiency of crew she was not seen as competent against the enemy.

Another ship owned by the King family and chartered to the Admiralty was the 76ton Albion. She was chartered between 1803-1812 for £3,626 a year and carried 6x4pound carriage guns and was crewed by 27 under Captain John May.

Charered between 1803-1814 for slightly less at £3,164 a year, was the 106ton Princess of Wales with 36 crew under Master James Slaughter and carried 10x12lb carronades.

The lute sterned Camperdown carried 14×12 carronades, had 53 crew under Master James Murray Cowham with Solomon Bevill. She was later owned by John Iggulden of Deal and chartered in 1804 for £4,677.

The 71ton Griffin had a crew of 24 and carried 6x3pound carriage guns, she was chartered between 1803 and 1805 for £2,106 per annum. While the 52ton Rose that had a crew of 20 and 6x3lb carriage guns was hired during 1803-1804 for £1,705 per year.

Fox renamed Friske in 1804 was a 98ton vessel with 30 crew and 8x4lb carriage guns owned by the Kings’ along with Collett and Thomsett. She was chrtered between 1803 and 1806 for £2,728 per annum.

The 163ton Althorpe – renamed Earl Spencer carrying 14x12lb carronades with 54 crew under Captain Thomas Chitty (b1763) was chartered in 1804 for £4,789 a year but foundered in the Channel in 1805. Thomas Finmore captained the 194ton Earl St Vincent with 60 crew and 14x12lb carronades and was chartered between 1804 and 1806.

Matthew King was the captain of the 129ton Drake with a crew of 43 and 12 x 12& 6lb carriage guns. The Telemachus carrying 40 crew with 10guns was chartered from the King shipyard between 1803 and 1804.

Ship owner, packet contractor and banker, Henshaw Latham owned a fleet of Dover built ships and chartered a number to the Admiralty. They included the cutter Countess of Elgin that was a privateer in the American War of Independence and had impressed the Admiralty such that they chartered her from 1803 to 1814. The Countess of Elgin’s Master was Richard Hammond and she was fitted with 8 carriage guns and had a crew of 25.

The 66 ton Duchess of Cumberland with a crew of 23 and 8x3lb carriage guns was chartered between 1803 and 1805 for £2,008 a year. Favourite, renamed Florence in 1804, was 72tons, with Master Abraham Hammond a crew of 25 and carried 6x3lb carriage guns, was chartered between 1803 and 1811 for £2219 a year. Charles Bostock was the Master in 1811 and a letter from Latham to the Admiralty, states that he was a very active and zealous man.

Other Latham ships included the 69ton Britannia with a crew of 24 and 6x3lb carriage guns, chartered 1803-1811 for £2,096; The 71ton British Fair with 6x3lb carriage guns and 3×12 carronades, she had a crew of 23 under Master Richard Rogers (1752-1835) and was chartered from 1803-1814 for £2,045 a year. While the 114ton Spider with 40 crew and 10x12lb carronades was chartered between 1803 and 1804 for £2,839 a year.

Businessman and banker, John Lewis Minet (1766-1829) also owned Dover built ships that he chartered to the Admiralty. They included the 163ton Earl Spencer with a reduced crew of 42 under Master William Forsyth and carried 12x12lb carronades. She had been sold to Minet by the King family after refloating and fitting out. This followed her foundering in 1805 and she was chartered until 1814 at the reduced rate of £3,832 per year.

The 98ton Joseph with 30 crew and 8x4lb carriage guns, owned by Minet along with James Cullen and John Gilbee was chartered between 1803 and 1809 for £2,721 per annum. The 181ton Fanny, with a crew of 28 under Master Thomas Gritton was chartered in 1804. The 100ton cutter Hind with 8guns and 30 crew under Master James Cullen was chartered in 1803/04 as a convoy protector for merchant ships. Together with Minet she was jointly owned by Collett, Thomsett and John Iggulden. The following year, they paid John Coad £4 19shillings to take the Hind from Chesapeake to Hampton Roads, in the United States, and from there out to sea without the assistance of another pilot.

The War was becoming more intensive by the beginning of 1805 as Napoleon, using his military strength, sought to tighten his grip on mainland Europe. His well-equipped and well-trained army under an elite of competent officers was still at Boulogne. England’s only substantial hope was with the Royal Navy so the Admiralty hired more Dover built ships to augment those already in service. These included the 114ton Courier with 12 guns and 38 crew from sail and ropemakers, Messrs Becker and Jell, for two years. They also chartered the 96ton schooner, Princess Charlotte from Henshaw Latham for one year paying £2,698. She was carrying 8x12lb carronades and had a crew of 30. On completion of the contract, the Princess Charlotte was chartered again and carrying just 3lb & 4lb carriage guns her crew was reduced to 12 and commanded a commensurate reduced fee. On this occasion the Admiralty chartered her as a despatch ship.

From the King shipyard in January 1805, the Admiralty bought the brigs Nightingale and Seagull, built to a John Rule design approved by the Admiralty, along with the gun-brig Resolute. The latter, Resolute, was about 200tons with 12x6pounder carriage guns, 20 swivel guns and a crew of 60. Following the Wars the Resolute was fitted out

as a diving bell ship at Plymouth and commenced this career based on the south coast. In 1826 the Resolute was transferred, in the same capacity, to Bermuda until 1844 when she was converted into a Convict hulk before being paid off in 1852.

On the Continent, Napoleon was still winning victory after victory and on 26 May 1805 had himself crowned King of Italy at Milan. Along the south eastern English coast Martello Towers – small, round defensive forts with thick walls – were being built from Folkestone to Lydd. To arm them, twenty-four and twelve-pound guns were landed at Dover. Ships from the British fleet were heading towards Cadiz, in Southern Spain, where Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson would join them to take command. At Cadiz were the joint French and Spanish fleets under the able command of Vice-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve (1763-1806).

By September 1805, Villeneuvre’s fleet was in an ideal strategic position to lead a maritime attack on Britain. Nelson had drawn up an offensive battle plan that centred on decisive combat when the French put to sea. His intention was to annihilate the enemy and put to an end to Britain having to accept a defensive stance.

Briefly, Villeneuvre’s fleet put to sea on 19 October 1805 with a combined fleet of 33 French and Spanish ships, while Nelson had 27 British vessels. At dawn, two days later, the two sides were in visual contact off Cape Trafalgar on the southern coast of Spain to the east of Cadiz where Nelson’s fleet was formed into two columns. This was risky, as it left the vulnerable unarmed bows of Nelson’s leading ships exposed, but he took that chance. Nelson’s strategy was to lead the first column into the attack and destroy the enemy flagship. This was the decisive part of the Battle as it would leave the French/Spanish, leaderless and confused, to be destroyed by the second column, led by Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (1748-1810). Once the enemy was so weakened, Nelson planned for the Royal Navy to deal with the remaining opposing fleet. That morning, Nelson sent his famous signal ‘England expects that every man will do his duty‘ to the fleet and the men cheered.

Battle of Trafalgar over the combined forces of the French & Spanish fleets by Frederick Stanfield Clarkson (1796-1867). Tate Gallery Wikimedia

The Battle of Trafalgar, on 21 October 1805, was hard going with the sailors on board the first 12 ships involved in the first confrontation, sustaining some 1,200 deaths and injuries. Nonetheless, as Nelson had stated, this was the decisive part of the Battle. Following this stage, the enemy was weakened and because the British maintained their speed and flexibility, at 14.15hours Villeneuve surrendered. However, at the height of the Battle, Nelson was mortally wounded and died at 16.30hours. In total, approximately 1,700 British, several from Dover, were killed or wounded, while the French/Spanish sustained 6,000 casualties and nearly 20,000 men were taken prisoner.

Thwarted, Napoleon turned his attention east where he routed the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz (now Slavkov u Brna, Czech Republic) on 2 December. Following the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson’s body was preserved in brandy to be brought back to England for a State funeral. His ship, the Victory, carrying Nelson’s body, arrived off the South Foreland on 16 December and came into Dover as a gale was blowing. She left on the 19 December for Chatham with Edward Sherlock (1743-1826), a Dover pilot, at the helm. From the Battle of Trafalgar until the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) in 1914, Britain had almost uncontested power over the world’s oceans, and it was generally acknowledged that ‘Britannia ruled the waves’.

The Battle of Trafalgar was a decisive victory in the Napoleonic Wars, but the confrontation was far from over, with many more battles and skirmishes to be fought before peace was restored in 1815. For instance, the 27 February 1806 saw action between the Royal Navy 38-gun frigate Hydra and the French brig Furet. Following the Battle of Trafalgar, the Furet along with three French frigates, managed to seek safety at Cadiz. Waiting for them to come out was Vice-Admiral Collingwood who had positioned the Hydra supported by the Dover built 385ton 18-gun sloop Moselle near the entrance to Cadiz harbour and positioned his heavier ships further out to sea. On the morning of the 23 February there was a strong easterly wind blowing and the Hydra and Moselle were blown off station. The French ships used the opportunity to make their escape. On seeing this, the captain of the Hydra despatched the Moselle to tell Collingwood who then gave chase. The ensuing fight culminated with the capture of the Furet. Of note, the crew of the Hydra shared the resultant prize money with the crew of the Moselle.

After the start of the second of the Napoleonic Wars, the Customs Riding officers became more effective and ruthless in dealing with smugglers. This led to those taking part in the industry becoming more evasive. This was exacerbated by a growing anti-smuggling campaign within the town, particularly orchestrated by Mayor Thomas Mantell. The upturn in Dover’s economy, brought about by victualling and provision of other services as well as shipbuilding, to the Navy and Military had given him the opportunity, in 1804, to demand the government to build a new Custom House to augment or replace the old one on Custom House Quay. This was on the north side of the Inner harbour or Bason – the present Granville Dock. The Government eventually agreed on condition that the town provided the land and when it opened, they said, they would increase the number of Custom officials including Riding officers. Land was donated, on Custom House Quay, by ship-owner John Minet Fector, next to his own premises and the new Custom House opened, with much pomp and ceremony, on 9 October 1806. At the ceremony Fector was thanked and praised much to the amusement of most of the crowd that gathered. It would seem that except for Mantell and his cronies as well as the Customs officials, most of the audience knew that Fector was East Kent’s smuggling Godfather!

On 27 November 1806 the King shipyard launched the 18-ton sloop Cherub and three days later, on 30 November, the brig Foxhound. That year they also built the 384ton brigs Belette, Forester and the Leveret. The last naval vessel built by the King shipyard at Dover was the 384ton brig Eclipse, launched in August 1807. John King then moved to Upnor on the Medway selling his Dover yard to James Duke (1791-1881), son of John Duke who had been a shipbuilder since the 1780s. James, with his brother John Henry Duke (b1787), operated as J.H. & J Duke shipyard. On his death in 1815, Thomas King was buried at St James Church and all his property and ships were ordered to be sold following which his Will was valued at £100,000.

Other shipbuilders commissioned by the Admiralty at this time included James Johnson (c1760-1824) who built them two cutters. The Cheerful was launched on 12 November and the Surely three days later. Although built to Admiralty specifications as fighting ships, Johnson ensured that the hulls were such that they could easily be converted into cross-Channel packet boats, cargo ships and smuggling vessels if necessary. The earlier suddenness of the Peace Treaty of Amiens (1802) and its disastrous effects on Dover’s economy had made everyone wary.

Albeit, the state of the harbour left a lot to be desired and the Admiralty, although the Royal Navy frequently used it, refused to pay for the privilege nor did they feel obliged to contribute to the cost of the badly needed repairs. Following the death of William Pitt, on 30 January 1806, Robert Banks Jenkinson 2nd Earl of Liverpool (1770-1828) was appointed the Lord Warden (1806-1828). A year later the ‘Case of Dover Harbour’ was presented to parliament in an attempt to extend the Tonnage Dues Act (previously called Passing Tolls) that were about to expire. This tax had been introduced in 1579 and granted Dover the right of charging all ships passing through the Strait of Dover with the proviso that the money collected was only to be used for harbour repairs.

In parliament, Lord Liverpool presented the argument to justify renewal of the Act and this was that the Harbour Commission had a debt of £9,000, the south-pier head needed rebuilding and an estimate of the cost was £25,000. Following the submission, parliament agreed not only to extend the Act for another period, but also to take the right of tonnage dues away from Rye as they had failed to construct a useful harbour, as they had promised to do since 1723. Further, the new Act stated that the dues were to be levied on all vessels from twenty to three hundred tons, passing from, to, or by Dover. That those laden with coal had to pay one penny on one chaldron (approximately 28 cwt, 3,136lb or 1422 kg) and the same for every ton of grindstone, Portland and Purbeck stone.

In January 1808, a storm did considerable damage to the harbour mouth. Repairs and new methods of trying to eradicate the continual build up of pebbles were undertaken by James Moon (1763-1832), the Harbour Master. He had built, a small dry dock and a basin for the use of shipbuilders. All of these works were completed before 1820 and the dry dock, it was planned, would fulfil a desperate need due to the damage sustained by the constant skirmishes, in the defence of the town and in the name of privateering. Since 1803 the increasing number of attacks on the town by French privateers firing red-hot shot into the heavily populated areas had caused a great deal of devastation. Then on 8 May 1808, a massive fire, after one of these attacks, destroyed the Fector warehouses, the largest in the town and on the sea side of the harbour. English privateers chased after the culprits, and although angry they took the crew prisoner rather than throwing them overboard, as they would have done in the past. Following disembarkation the prisoners were taken to the town’s goal before being moved up to the Castle. In his diary, Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819) recorded that three escaped by boat, but they were pursued and recaptured by Dover mariners, in the Channel despite thick fog.

As the Wars progressed, the Admiralty hired more Dover built ships. Back in 1803 they had chartered the cutter, Lord Nelson II, owned by Samuel Collett and they chartered her again five years later, this time for two years. Unfortunately she was lost on 5 August 1809 with all hands. At the same time as they chartered Lord Nelson II for the 2nd time, they chartered the 50ton lugger Ox with 22 crew from Robert Hammond (1779-1826) and Captain John Blake for one year. A lugger is a two or three masted sailing vessel with lug, or four cornered (square) sails, suspended from a yard. In 1809 the cutter Dover, owned by sailmaker Thomas Spice (1765-1839), of Snargate-over-Sluice – now Union Street – was chartered once again. Her Master was William White, she had a crew of 13 and was chiefly to be used as a dispatch ship.

They were part of Sir Richard John Strachan’s (1760-1828) fleet. He was appointed Commander-in-Chief, North Sea watching the Dutch coast between 1809-1811. Two more Dover built ships were also part his squadron based off Flushing (Vlissingen), on the island of Walcheren in the West Scheldt River estuary. One of these ships was the 71ton cutter, Princess Augusta, carrying 8x12lb carronades and 30crew, owned by John King. She had been in constant service since 1803 and remained so until 1814 for which the King family were paid £2,240 a year. The other was the 74ton schooner, Flying Fish, under Master William Mate (1768-1833), owned by Henshaw Latham, chartered in 1809 and remaining in service until the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Bombardment of Flushing in the 1809 Walcheren Campaign. British Battles on Land and Sea, volume 3, British Library.

On 9 June 1809, Strachan was appointed the naval commander of an expedition to destroy the French arsenals on the swampy island of Walcheren. This expedition was the largest in the Peninsular Wars (1807-1814) that were part of the Napoleonic Wars. His fleet consisted of 264 warships and 352 transport ships, some of which were built in Dover as mentioned previously. They were carrying 44,000 troops, some 15,000 horses, field artillery and two siege trains. The expedition landed on Walcheren on 30 July 1809 at the height of the mosquito season. Some 4,106 men died of which 4,000 died of malaria, known at the time as Walcheren Fever and the French lost about the same percentage of troops to the disease. When the campaign was abandoned nearly 12,000 men were still sick and most of those who survived the illness remained permanently weakened. Strachan was blamed for the expedition’s failure but in his defence, he did make it clear that the ships had done all that had been required of them.

In 1811, the Admiralty hired more Dover owned and built ships. These included the Henshaw Latham’s cutter the Countess of Elgin; the 118ton schooner Charles with 40 crew owned by Thomas Lloyd (1766-1820) and the 183-ton schooner, True Briton with 30 crew owned by John Gilbee and sailmaker Peter Popkiss (1750-1822). The Royal Navy wanted to charter Fector’s flagship, ex-Royal Navy 70ton sloop, King George I, built by the King shipyard and the fastest ship on the cross Channel packet run. However, Fector reminded the Admiralty that they had already chartered the 58ton cutter, King George III that carried 6x4lb carriage guns with a crew of 22 under Master Thomas Mercer, on an agreement that was made in 1803 for £1886 per year and due to run until 1814. She was owned by a consortium consisting of Fector, Matthew King, Steven Collett and Thomsett. He then successfully suggested that the Admiralty charter his 160ton cutter Nymph armed with 10x4lb carriage guns and crewed by 23 men under Master James Boxer and partly owned by James Boxer.

Privateering by both British and French mariners continued, with the French increasingly homing in on Dover ships. Typically, on 13 January 1811 four privateers off Folkestone set upon Fector’s ship, Cumberland, under Master John Hammond (1780-1854) on her way home from Quebec, Canada. During the confrontation, the French boarded her three times, but the Cumberland’s crew managed to fight them off. The fracas finished when the Cumberland, firing a number of rounds, disabled at least one of the French vessels. On arriving in Dover, Captain Hammond reported that the Cumberland had lost one man and that the mate was injured but that they had taken three French prisoners. He also reported that during the encounter, the crew of the Cumberland had killed sixty French privateers but this was never substantiated.

Another shipyard opened on Dover beaches in 1812 owned by Thomas Vincer (1789-1859). He was born in Dover in 1789 becoming a Freeman in 1812 having served his apprenticeship in his father William’s shipyard and on completion his father leased him his own yard in Fishermans Row. The year was particularly special for Vincer, for not only did he become his own master, he married Margaret Marlow of Deal. They went on to have 12 children but dark clouds were gathering for Dover shipyards due to the lack of orders for new ships by the Admiralty. At about that same time as Thomas Vincer married Margaret, it appears that the Ladd shipyard closed.

A typical Clipper – the Westward-Ho in 1852. State Street Trust Company, Boston, Massachusetts. Wikimedia

On the international front there was increasing tension between Britain and the United States of America (USA) as US traders took advantage of Britain’s lack of resources due to the demands of the Napoleonic Wars. To try to deal with the US problem, in 1812, Britain implemented trade restrictions on the country. As a result, the US retaliated by declaring war on Britain – the United States War of 1812-1815. A number of Dover built ships owned and chartered by the Admiralty were sent to escort the British merchant shipping along the US/Canadian coast, as these merchant ships were coming under increasing attacks. The British also implemented a blockade of US ports. To run the blockade, the US developed the clipper, a form of either a schooner or a brigantine but developed for speed. Dover seamen that had been recruited by the press gangs and were on board the British ships took note of the design of this new style of US ship. They brought these drawings back to Dover and on the town’s beaches, shipbuilders used their expertise to recreate the design. The Admiralty, however, was not interested as they did not conform to their specifications. Nonetheless, the more affluent local ship owners such as Fector and Latham were and they purchased the Dover type clippers.

The Napoleonic Wars were not confined to the European mainland, but also included the Caribbean and South America. One of the Dover built ships involved in the West Indies Campaign (1804-1810), was the 18ton sloop Cherub, launched by the King shipyard in 1806. In 1809, she was under the command of Thomas Tudor Tucker (1775–1852). Following the capture of Martinique on 24 February 1809 the Cherub was reclassed as Sixth Rate and carried 20guns. Eventually British naval forces dominated the seas in the West Indies and in the following year every single French, Dutch and Danish colony was firmly under allied (mainly British) control. The Cherub was then sent to South America and together with the 60ton cutter Dover and the Phoebe formerly the Betsy, carrying 6x12lb carronades and 20 crew – on loan to the Royal Navy by Fector for £1,905 a year, they took on the United States frigate, Essex at Valpariso, Chile, on 28 March 1814.

The following month, on 6 April 1814, following the capture of Napoleon, the Chaumont Peace Treaty was signed and the former Emperor was imprisoned on the Isle of Elba, in the Mediterranean. On Saturday 23 April Louis XVIII (1814-15 & 1815-24), arrived at Archcliffe Fort aboard the Jason. He was on his way to being restored to the throne of France after 21 years in exile and was received by a guard of honour headed by Mayor John Walker. The following day, after spending the night at Fector’s Pier House, on Strond Street in the Pier District, the King left for France. The shipbuilding fraternity had already recognised that their heyday was over unless smuggling increased or another outlet for their ships was established. However, on 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from imprisonment on Elba and quickly reassembled his Grand Army. Determined to regain his supremacy Napoleon prepared for battle and Dover became a hive of activity as troops embarked on Dover ships for Holland.

On the Continent, the events were going Napoleon’s way and by 15 June 1815, he was advancing towards Brussels. The next morning Napoleon’s forces attacked the Prussians, driving them back and splitting the allied defence. He next attacked the British, under the command of Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852), who had been previously elevated to the Duke of Wellington in 1814. Wellington withdrew to a ridge across the Brussels road near the village of Waterloo and the ensuing Battle took place on 18 June 1815. The British victory brought Napoleon’s reign and the Napoleonic Wars to an end. It was later reported that during the Napoleonic Wars the Royal Navy lost 344 vessels due to non-combat causes, 75 by foundering, 234 shipwrecked and 15 from accidental burnings or explosions. In the same period the Royal Navy lost 103,660 seamen: 84,440 from disease and accidents, 12,680 by shipwreck or foundering and 6,540 by enemy action.

The Cesar, a French Man O’War model made out of bones from the food rations by a French Prisoner of War during the Napoleonic Wars. Dover Museum

Shipbuilding Part 4 follows

Presented: 20 July 2018