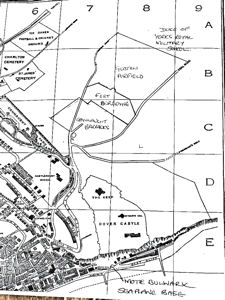

Mote Bulwark is given as Battery on this 1890 map to the north west of Guilford Battery overlooking Marine Parade. The Seaplane Base included the lower part of these sites and crossed Marine Parade to the sea.

Dover Seaplane Base and Mote Bulwark, the ruins of the latter can still be seen, were on the east side of Dover Bay close to the present day A20 access road to Eastern Docks. Although both played important roles in Dover’s, and indeed national history, these days they have been almost forgotten. Further, following a recent presentation of part of the story in Dover, when there was a call for a plaque to be erected as a reminder, a member of the audience with a lot power, argued vociferously against this as a waste of money! Nonetheless, Doverhistorian.com, has expanded the story from that given at the presentation and is leaving it to readers to make up their minds whether the story is worthy of interest. It is presented in two parts, Part One from the founding of Mote Bulwark and the World War I Seaplane base to the summer of 1916. Part Two takes the reader from the summer of 1916 and the development of the seaplane base, to changes that have occurred from the inter-war period to the present day.

1. The history of Mote Bulwark

England in the late 1530s was in danger of invasion from the combined forces of France and Spain. France was England’s historical enemy and Henry VIII’s (1509-1547) divorce of Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), had upset her nephew, Charles V Holy Roman Emperor (1519-1558) and King of Spain (1516-1558). ). On 18 June 1538, Francis I of France (1515-1547) and Charles V signed the Truce of Nice, this raising the possibility of invasion of England. Consequently, Henry instituted a massive defensive programme around the east and south coasts that included the building of Castles at Deal, Walmer and Sandown. In Dover, to defend the harbour, three batteries or bulwarks were begun in March 1539. The first, on the western side of the Bay, was situated on a small platform cut into the cliff with caves for the magazine but had disappeared by 1568. The second battery was also on the western side of the Bay and eventually became Archcliffe Fort and both batteries were aimed at protecting the recently created harbour on the west side of the bay.

Shortly before, the sea came up to the foot of the cliffs below the Castle but due to the Eastward Drift, a natural phenomenon that deposits shingle along the coast line of Dover Bay, the sea was starting to recede leaving the Castle vulnerable. It was for this reason that the third battery was built and was known from the outset as Mote Bulwark – from Mote and Bailey a defensive structure enclosed by a wall or palisade. Like the other two bulwarks, it was made of earth revetted with timber but was more elaborate than the other two. The Mote Bulwark consisted of a long platform with two semi-circular gun ports pierced by six gun loops for mounted cannons. Behind the platform there was a long timber building which was probably a store house with the battery connected to the Castle by a tunnelled stairway. Completed by midsummer 1540, the total cost for the three bulwarks was £1,496 and to pay for these the King appropriated lands from Dover Corporation! Following the crisis, Mote Bulwark remained occupied by the military and at the time of the Henry VIII’s death in 1547, the battery had five pieces of ordnance of mixed calibre.

The Bulwark was again put on alert during the Spanish Armada of 1588 when a defensive extension was built along the shore to the Three Gun Battery, at the east end of present day Snargate Street. In 1607-1608, an Assessment of Ordnance in Kent stated that a Captain, two soldiers, one porter and two gunners manned Mote Bulwark. War with Spain again threatened in 1623 and a survey was undertaken of Dover’s military strength. Following much needed repairs to the Mote Bulwark, the Castle and Archcliffe Fort, all three were reported as being of a sound condition. The cost of these repairs came to £1,048 17shillings and the Mote Bulwark was mounted with 6 guns.

England’s King Charles I (1625-1649) had been at loggerheads with Parliament and this culminated, in mid-1642, in the Civil Wars (1642–1651). Kent was under Parliamentary rule in 1647 when the government decreed that Christmas festivities were illegal. Canterbury townsfolk refused to obey and their disobedience culminated with a rampage through the city with the crowd shouting, ‘For God, King Charles and Kent!’ The rioters took control of Canterbury until a force of some 3,000 Parliamentarians recaptured the city and subsequently, a special court was convened. The carefully selected jury were designed to return a verdict of guilty but instead, they used the opportunity to instigate a petition. This not only angered the Parliamentarians it led directly to the Kent Uprising (1647-1649) in which the Mote Bulwark played a pivotal part.

Dover Castle by Wenceslas Hollar (1607-1667). Mote Bulwark is at the foot of what appears to be a cleft below the Castle. wikimedia commons

By May 1649, Walmer, Deal and Sandown Castles were captured from the Parliamentarians and the fleet, lying in the Downs, took the rebels side. This meant that only Dover Castle was in the hands of the Parliamentarians. One of the rebel leaders, Sir Richard Hardres (1606-1669), together with local Royalist, Arnold Braemes (1602-1681), marshalled some 2,000 men to mount an offensive and they seized the Mote Bulwark. The battery was full of ammunition and this they used to attack the Castle towers and corners. Although they fired some 500-cannon balls at the Castle, these were ‘without doing any material injury‘. Meanwhile, Parliament dispatched troops of the New Model Army under the command of Colonel Nathaniel Rich (1614- c1701) and Colonel Birkhamstead to retake Sandown, Deal and Walmer castles, and raise the siege at Dover. Colonel Birhamstead’s troops relieved Dover Castle on 6 June, which spelt the end of the uprising and the Civil Wars came to an end. This was followed by the Commonwealth (1649-1653), under the rule of a Republican Council of State headed by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), as the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England becoming, in 1653, the Interregnum (1653-1660).

In October 1651, Cromwell introduced the Act of Navigation (1651), which in essence meant that any goods imported into England or transferred from one English colony to another could only be carried in English ships. This meant, for instance, Dutch ships passing through the Strait of Dover were searched and goods deemed as unlawful were confiscated. Further, all foreign ships had to strike, that is, lower their flag in acknowledgement of English supremacy, when passing Dover Castle. It was only a matter of time before a confrontation took place and this happened on 19 May 1652. The Dutch Admiral Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp (1598–1653) was leading a convoy of 44 ships along the Downs, off the east coast of Kent, and he refused to strike when he met the English fleet of fifteen vessels, headed by Admiral Robert Blake (1598–1657). In response, Blake ordered a shot to be fired across Tromp’s bows to which the Admiral retaliated with a broadside and a fierce battle began lasting 5 hours.

Possibly the Battle of Dover 1652 – A naval battle on choppy waters 1652 by Catharina Peeters- wikimedia commons

The guns of the Castle and the Mote Bulwark fired but they lacked sufficient range to be of any use. The English were only saved by the poor gunnery on the part of the Dutch, which gave them time to send for reinforcements. Thomas Kelsey (d 1680) was, at the time, the Captain of Dover Castle and he arranged for eight ships from Dover, under the command of Captain Nehemiah Bourne (c.1611–1690), to join Blake’s fleet. At the same time, John Dixwell (1607-1689), Dover’s MP, used special powers to raise a county militia to guard the coast. During what was later called the Battle of Dover (1652), Blake’s forces sank one Dutch ship and took another. At nightfall the Dutch fleet retired towards Holland.

Following the Battle of Dover, Mote Bulwark was strengthened and the number of men increased. Later in 1660, saw the Restoration of Charles II (1649-1685). On 4 August 1661, the Dutch artist, Willem Schellinks (1627-1678), who kept a diary of his travels in England between 1661-1663 reported that he and his party visited Sir Wadeward the Commander at Mote Bulwark. Apparently, they were ‘hospitably entertained by him with claret wine.‘ During the visit, the Ambassador representing Frederick William the Elector of Brandenburg (1640-1688) embarked on a ship to Calais. He had been in England to discuss the guardianship and education of the ten-year-old orphaned Prince William of Orange (1650-1702), whose late mother, Mary, the Princess Royal (1631-1660), was the sister of Charles II. As Charles II’s reign progressed the Castle garrison was reduced and so was Mote Bulwark’s.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 led to Prince William of Orange becoming England’s William III (1689-1702), who along with his wife Mary II 1689-1694), the daughter of Charles II, ruled the country. By that time, the Castle was in a ruinous and unarmed state and the tiny remaining military contingency had moved into the equally neglected Mote Bulwark. In 1691, fearing an invasion from France in support of the deposed James II (1685-1688), repairs were made plus installing 45 guns at the Castle and 11 at Mote Bulwark.

Rebuilding of Mote Bulwark with stone, was started sometime before 1737 and was sited below and to the west of the older Bulwark. This rebuilding was possibly provoked by the raising international tensions that eventually led to the Wars of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). The Wars involved, amongst other nations, the ancient foes of England and France. The new Mote Bulwark consisted of a series of terraces cut into the cliff and in front of the lowest one was a new semi-circular Battery that had places for eight guns. On a higher terrace there was a paved area in front of a building which was marked on the Plans as the ‘Master Gunner’s House’ and nearby was another building labelled ‘Guard Room and Store House’.

Mote Bulwark – Detail of the gate from which the stairs led up to the Castle, also part of the 18th century gun platform. Alan Sencicle

The semi-circular Battery was enlarged in 1755-1756, as part of an extensive programme of defensive works at the Castle. They were being undertaken in order to address the potential of the Castle for artillery defence. Other works included the building of a number of Castle batteries, improving the defence of landward approaches from the north and east, and lowering the towers of Fitzwilliam Gate and Avranches to give the Castle guns a field of fire. A description of about 1772 states that Mote Bulwark consisted of a gate with rooms above and on both sides, a house for the gunner and an angled flight of brick steps connecting the different levels. The entrance to Mote Bulwark was from the east by a gradual ascent.

During the American War of Independence (1776-1783) France supported the colonials and Britain, fearing an invasion, strengthened the national defences. Four Batteries were built around the Bay by Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821). They were Amherst Battery – east of where the Clock Tower is today; Townsend Battery close to the present day Lord Warden House; North’s Battery, in front of New Bridge – present day Granville Gardens; and Guilford Battery, below Mote Bulwark. The latter was built on a spur of land that had accumulated following the building of Castle Jetty in 1753 – a wooden pier below the Castle. Guilford Battery, like North’s Battery, was probably named after Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (1732-1792), who was the Lord Warden (1778-1792). At this time, Guilford Battery was armed with four 32-pounder guns and a number of carronades. Mote Bulwark’s defences were also repaired and these, according to financial statements, cost £1,200. The Castle Guard at Mote Bulwark were also in charge of the four new Batteries and they were manned by Volunteers of the Dover Association formed by Thomas Hyde.

Just before the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), the Guilford Shaft was excavated to link Mote Bulwark with the Castle on the cliffs above. In 1813, Reverend John Lyon (c1838-1817), vicar of St Mary’s Church wrote, ‘near the edge of the cliff, and not far from the end of the wall, a shaft has been sunk, one hundred and ninety feet deep, to form a communication with Mote’s Bulwark … In this shaft there are circular stairs, and when the Prince of Wales* visited the Castle in 1798 he was conducted down it, as the nearest way to the town.’ *The Prince of Wales was later George IV (1820-1830).

Troops outside the Castle Casemate Barracks . Watercolour by William Burgess, circa 1840. Dover Museum

A few months later, the Casemate Barracks were begun. Designed by Lieutenant Colonel William Twiss (1745-1827) they too were excavated in the chalk cliff and provided accommodation for soldiers. Initially, there were four parallel tunnels extending approximately 100-feet into the cliff with vertical ventilation shafts and reached by a terrace that extended from just above Canons Gate. Three larger tunnels with ventilation shafts and a communicating tunnel, were excavated in 1798 to provide officers quarters. Later another communicating tunnel was built along with another entrance out onto the cliff face. The tunnels and the cliff face were finished with bricks – the windows, casemates, verandas and brickwork can still be seen from Townwall Street, above Mote Bulwark. It was said that in Casemate Barracks, one room could accommodate 200 men. These rooms were lit by oil lamps and heated using fireplaces and the chimneys took the smoke out through the top of the cliffs. The men slept on iron bedsteads.

Also under the auspices of Lieutenant Colonel Twiss, in April 1804, the building of the defences on Western Heights began. Strong defensive lines linked the Citadel – the main defence – that was also strengthened with a Redoubt on the eastern side. The Drop Redoubt, as the fortification was called, and the North Centre Bastion along with bombproof barracks and connecting lines were constructed at about the same time. Other works included a defensive canal between the Eastern and Western Heights, since long gone, and considerable defensive works including one at St Margaret’s Bay, that can still be seen and along the coast to the west, Martello Towers.

Castle Casemates above Mote Bulwark facing the Seafront. Originally excavated for barracks, during World War II they were the offices of the Commander-in-Chief of Fortress Dover. Alan Sencicle

Napoleonic prisoners of war were held at the Castle and the caves that had formed in the cliffs at sea level were used to house them. To while away their time the prisoners made carvings and some of these works, it was said, were spectacular. In 1894, a Captain Lang gave the Cesar, a Man o’ War model, believed to have been made by a French prisoner out of bones left over from food rations. The ship can still be seen in Dover Museum. The caves are now in the care of English Heritage as part of its Dover Castle property.

The strip of shingle, at the foot of the eastern cliffs under the Castle, created by the Eastward Drift, continued to widen and in the late 18th century, Captain John Smith owned the newly created land east of Mote Bulwark. By 1816, there was a windmill and makeshift residences on this land. Sir Sidney Smith (1764-1840), the son of Captain Smith, sold the land to Willson Gates (c1758-1844) a builder who started the development of East Cliff and the adjacent Athol Terrace that we see today. Most of the major building programme took place between 1817 and 1840 but in 1847, when Colonel William Burton Tylden (1790-1854) was undertaking an audit of Dover defences, he was none too happy. He reported that three 18pounder guns were mounted on Mote Bulwark but that their fire was restricted by these developments at East Cliff. To deal with the problem Guilford Battery parapets were raised and 42-pounder guns installed on traversing platforms.

To ease access, in 1870 a double set of stairs was built from the Castle to the Casemates and by May 1886, the Guilford Battery was armed with six 8-inch, 65 cwt smooth bore guns. However, not long after it was recommended that they be removed, possibly due to their relative lack of firepower and the proximity of the East Cliff dwellings, and thereafter artillery remained for ornamentation only. By that time, Fort Burgoyne, north of the Castle, and Castle batteries on the cliffs above Mote Bulwark, both armed with heavy guns, formed the real line of defence on the east side of the Bay. On the west side, similar armaments had been placed on Western Heights and together, this ensured that the whole Bay was protected. Of the Thomas Hyde Page’s original four Batteries, erected c1775-1783, only Guilford Battery remained and this had been disarmed. Eventually the building became the Headquarters South East Military District and a drill hall was built for the Territorial Army.

Work started on Dover’s Admiralty Harbour in 1898 and the cliffs at the east end of the Bay were cut back. The Eastern Arm of the new harbour, 2,800-feet (approx. 854 metres) in length and with depths between 26-32 feet (7.93-9.8 metres), was started in January 1901 and completed by 1904. The Admiralty Harbour was officially opened on Friday 15 October 1909, by George Prince of Wales later George V (1910-1936). Sir William Crundall (1847-1934), chairman of Dover Harbour Board (DHB), laid the last coping stone on the widened part of Admiralty Pier on 2 April 1913. A month later work started on building the Marine Station at the landward end of Admiralty Pier with the foundations having been filled in by 1 million cubic yards of chalk taken from the eastern cliffs (see Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Railway Line part I). To enable the chalk to be transported across the bay Castle Jetty was extended and used for this purpose.

Prior to World War I (1914-1918) Mote Bulwark came under the care of the Ancient Monuments Branch of the Ministry of Works and no longer played a part in defence. Part of the old Guilford Battery grounds, next to the Territorial Army Drill Hall were rented out and it became a popular County Roller-Skating rink. The rink doubled as a dance hall that was equally, if not more popular. From September 1911, the remaining part of the grounds was used as an open-air theatre and cinema.

2. Seaplanes part one

On 31 October 1908 Louis Blériot, (1872-1936), designed a monoplane that managed to fly a distance of 17 miles from Toury to Ateny both in Northern France, making two landings en-route and setting a record for distance flown. Two weeks before, 16 October, a former American cowboy, Samuel Cody (1867-1913), made the first powered flight in the British Isles. Together, these two events led the Daily Mail to offer a £1,000 prize to the first person to cross the English Channel in a heavier-than-air machine. This Blériot achieved on Sunday 25 July 1908, flying his Blériot No XI 25-horsepower monoplane from Sangatte, on the northern coast of France, to Northfall Meadow behind Dover Castle. From then on the development in aviation was rapid.

Orville & Wilbur Wright followed by Horace Short. The Short brothers won the right to build Wright planes. Eveline Larder

By 1910 the Dover Aero Club was established at Whitfield and was described as the ‘first air station in England.’ In fact this was an exaggeration as the airfield that earned the accolade with Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, where Horace Short (1872-1917) and his brother Oswald (1883-1969) also opened the World’s first aeroplane factory at Mussell Manor in 1909. Flight magazine, was also founded in 1909 as ‘A Journal devoted to the Interests, Practice, and Progress of Aerial Locomotion‘, described the Dover club, in 1911, as ‘one of the most powerful aeronautical clubs in the country.’ At that time, the president was John Charles Pratt, 4th Marquess Camden (1872-1943) Lord Lieutenant of Kent (1905-1943) and the vice presidents included Field Marshall Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), and Admiral of the Fleet, Lord John Rushworth Jellicoe (1859-1935). Ironically, during the pending War neither of these two gentlemen were particularly enthusiastic about the use of air support in combat.

Harriet Quimby 16 April 1912, next to the Blériot monoplane with a 50hp Gnome engine at Whitfield aeropdrome. Giacinta Bradley Koontz.

On Tuesday 16 April 1912, aviatrix Harriet Quimby, (1875-1912), was the first woman to successfully fly across the Channel from England. She set off from Whitfield airfield and there is a plaque commemorating her achievement at the Ramada Hotel, Whitfield.

In the summer of 1913 the Daily Mail offered £5,000 for the first hydroplane, waterplane or seaplane capable or rising and alighting on water and flying a 1600-mile set course. The race was organised by the Royal Aero Club and started at Netley, Southampton Water. Each plane taking part had to stop for 30 minutes at eight control points and complete the course in 72hours or less. It had originally been planned that one of the compulsory stops would be Dover but by that time Europe was politically unstable and following the Aerial Navigation Acts of 1911 and 1913, Dover Harbour was a prohibited area. The alternative compulsory stop became Ramsgate and when the seaplanes flew near Dover they were obliged to pass at least 900yards from the end of Admiralty Pier, while the height above sea level was not to exceed 300feet. Finally, with the coming hostilities in mind, a report noted that seaplanes would be efficient at reconnoitring and in the detection of hostile submarines as submarines could easily be seen underwater by seaplanes travelling at great heights. Thus, it was mandatory for both the contestants and machine to be British.

Back in 1862, the Royal Engineers had undertaken the first military aviation experiments in Britain. By 1878 the first Air Estimate of £150 was passed by Government to enable aviation research to be undertaken. Six years later balloons were used in the Bechuanaland Campaign (1896-97) – now Botswana, South Africa – by the army. They were quickly recognised as of value and balloons were frequently used and saved British troops from ambush. In 1890 the Royal Engineers were granted a full Balloon Section with its own factory at Farnborough Airfield, Hampshire, from which developed the first Royal Aircraft Establishment.

The first British person to actually take off and land on water in an aeroplane appears to have been Commander Oliver Schwann / Swann (1878-1948), in 1910. Credit for building the first successful seaplanes goes to the Short brothers on the Isle of Sheppey (see above). By 1911 the Royal Engineers had an air battalion of two companies – Number 1 for airships and Number 2 for aeroplanes. They also received a grant from government of £85,000 and the following year the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) formed. Made up of a naval wing and a military wing the aviators were trained at the Central Flying School, at Upavon, Wiltshire.

Short Folder seaplane (S.64), serial number 81, being hoisted out from the Royal Navy ship Hermes with wings folded. wikimedia commons

On 7 May 1913 the Royal Navy cruiser Hermes was specially commissioned and fitted out as the first experimental seaplane carrier. Under the command of qualified pilot Captain Gerald William Vivian (1869-1921) the Hermes had a launching platform and room to stow 3 seaplanes. His team were all Royal Navy aviators and included Francis Rowland Scarlett (1875-1934), who eventually reached the rank of Air Vice-Marshal; James Louis Forbes (1880-1965) who eventually reached the rank of Air Commodore in the Royal Air Force and Francis Esme Theodore Hewlett (1891-1974). He was the son of Hilda Beatrice Hewlett (1864-1943), the first English aviatrix to earn a pilot’s licence. Hewlett retired as a Group Captain in the Royal Air Force and emigrated to New Zealand where he distinguished himself in World War II (1939-1945) and was promoted to Air Commodore.

Trials then took place to test launching and recovery methods and soon Captain Vivian and his team had developed tactics for use in fleet operations. Then on 23 December, Vivian was ordered to pay Hermes off and give the crew Christmas leave. At first effectively mothballed, the Hermes was recommissioned by Commander (later Air Vice-Marshall) Charles Laverock Lambe (1875-1953) on 31 August 1914 as a seaplane tender.

Vivian team’s work on the Hermes had impressed the Admiralty who procured the Ark Royal that was being built by Blyth Shipping Company, Northumbria for the Royal Navy. On the advice of Vivian and his team the Ark Royal was modified to accommodate seaplanes and she was launched on 5 September 1914. Spending most of World War I in the Mediterranean, in 1922 the Ark Royal was placed on reserve with occasional recommissioning. In 1932 she was renamed Pegasus and in World War II, amongst other duties, she served in her original role as a seaplane carrier. Following the War, the grand old lady was sold to a Panamanian company but was seized, in 1949, for debts and scrapped the following year.

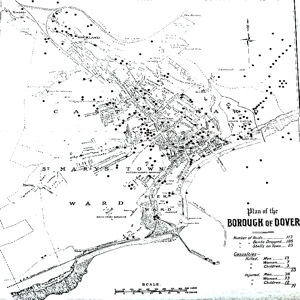

As a preparation for the impending World War, in June 1913, the Royal Navy requisitioned Guilford Battery and the surrounding grounds. At the outbreak of War the area became the base for the Royal Naval Seaplane Patrol station as part of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The naval wing of Royal Flying Corps became the RNAS on 1 July 1914 and on 1 August 1915 the RFC that had remained as the military wing, was officially separated from the army. At the time War broke out, RNAS was made up of 127 officers and 500 men with 93 single seater seaplanes, 6 airships and 2 balloons.

Some of planes including Short S41 tractor were based at Dover. A hangar was built in the Guilford Battery grounds that had previously been used for an open-air theatre/cinema. At the same time the skating rink was converted into workshops and the Territorial Army building, a training school. The whole came under the command of Sheerness Naval District and officially named the Dover Hydro Aeroplane Station. At the time, the flying boats lay at anchor in Admiralty Harbour but due to difficulties were only hoisted out for major repairs. This was done by the use of steam cranes on the eastern arm, where the repairs were carried out until the hanger was built. Then the seaplanes were manually carried over Marine Parade until the steam cranes were moved there.

In May 1914, British pioneer aviator, Gustav Hamel (1889-1914), left Hardelot aerodrome, near Boulogne, France to fly to Hendon aerodrome, north west London. He then disappeared and was last seen heading for the Channel. Hamel was flying a Morane-Saulnier monoplane and when he left a stiff westerly wind was blowing plus mist over the Channel. The light cruiser Pathfinder and four Admiralty boats (t.d.s), Mullard, Osprey, Star and Bat, left Dover harbour in a vain search for Hamel. They were joined by a number of boats from the Royal Navy base at Nore in the Thames estuary and two seaplanes.

By the evening the wind had become stronger and shifted to a north-easterly direction when Seaplane number 72, piloted by Lieutenant Brodribb was about to land in Dover harbour. A heavy gust capsized his plane off the end of the Prince of Wales Pier but luckily Lieutenant Brodribb managed to escape and was rescued. Although the plane stayed afloat, the rough sea quickly broke it up and this raised caused concerns over their vulnerability. It was not until 6 July that anything was known of what had happened to Hamel, on that day the crew of a fishing vessel sighted what appeared to be his body off Boulogne.

At about the same time, mobilisation in preparation for War was taking place in Germany and most European countries, while in the UK, in order not to appear alarmist, such preparations were subjected to government spin. Typically, there was a flat denial that the works at Mote Bulwark were for the establishment of a seaplane base even though local workman were well aware of what they were building! While a news bulletin stated that the large squadron of seaplanes seen in Dover Harbour were there in order for George V to undertake a review!

How the authorities were going to explain away the constant stream of seaplanes flying over Dover on their way to Calshot, Southampton, where the RFC had established a Naval Air Station in March 1913, had become a local betting game! That is until one of the seaplanes broke down and landed in the harbour. According to the report published in the Dover Express of 17 July 1914, the seaplane was ‘was one of the latest type of machines with a very powerful engine and although great in size, by its wings folding back it could be reduced to such small compass that there was no difficulty stowing it away on the upper deck of the Shannon. It resumed flight at a quarter past ten.’ Four days before, a Short type 74 seaplane had broken down near St Margaret’s Bay and was towed into the harbour on 13 July. A Dover Express photographer was there to capture the scene.

Land at Swingate and a private airfield at Capel were commandeered by the RFC. The Swingate site was to be converted into an airfield for military purposes and it was talked about Capel becoming an RNAS airship station. On 3 August 1914, thousands of people came to Dover from the surrounding areas and as a far away as London to see the preparations that were being made for War. At 13.00 the French cruiser squadron of six ships came up the Channel and the crowds lining the cliffs, cheered. During the evening the first aeroplanes arrived at Swingate where approximately £14,000 had been spent to create the Military Aeroplane Station, as it was then called.

The pilots of aeroplanes and seaplanes, at that time, did not possess any armaments other than their own revolvers, automatic pistols and rifles. Experiments in the use of machine guns had been undertaken and in early 1914 the details of a device that would enable a machine gun to fire through the propeller had been submitted to the War Office. However, it was generally believed that the main use of aircraft was reconnaissance so they would not be participating in combat. While some, such as Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), who commanded the British Expeditionary Force, saw even this role as unnecessary. He was of the firm opinion that soldiers on horseback best undertook reconnaissance and that aeroplanes were strictly for recreational use.

At 23.00hrs on Tuesday 4 August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. Immediately notices were signed by Mayor Edwin Farley (1864-1939) and Brigadier-General Fiennes Henry Crampton (1862-1938), the Dover Coast Defence Commander. The port and town of Dover were declared to be ‘Fortress Dover’ with the headquarters at the Castle and Rear Admiral Horace Hood (1870-1916) was appointed the Commander in Chief of Fortress Dover, and the next day Brigadier-General Crampton was promoted to the General Officer Commanding (G.O.C.) Fortress Dover. Notices were distributed that stated mobilisation had been ordered and the Defences of Dover had been placed on a war footing on both land and at sea.

Entrance and exit to Dover could only take place by the railways and the main roads to Folkestone (old A20), Deal (A258) and Canterbury (old A2). Special ‘Dover Garrison’ passes, limited in number, were necessary for all those who required to enter or leave the town, whether they were military, naval or the general public, and were issued by Dover’s Chief Police Constable David Fox (1864-1924). The Military Authorities had the power to arrest and search. All local newspapers were subject to censorship by the military and anyone approaching any defensive works was to be stopped, questioned and searched. The South East and Chatham Railways triple screw turbine packets, Empress II launched in 1907, Engadine and the Riviera both launched in 1911, were commandeered by the Government and fitted out to carry sea planes.

Guston Aerodrome off Deal Road. Duke of Yorks school clock tower can be seen. Dover Transport Museum

On 55acres of farmland between Fort Burgoyne and the Duke of York’s school just off the Deal Road, to the east of Dover, an officers’ and ground crew messes were constructed. Also tin accommodation huts (later called Tin Town) for the RNAS personnel. Adjacent, on a field that was commandeered by the RNAS, a runway of hardened earth was laid and named Guston aerodrome. Initially used for RNAS aeroplanes to carry personnel and goods to the Mote Bulwark seaplane station it became a main base for RNAS aeroplanes.

The British Expeditionary Force left for France between Sunday 9 August and Thursday 13 August escorted by Dover seaplanes, along with seaplanes from elsewhere and aeroplanes from Guston and Swingate. The first pilot to arrive was Lieutenant Hubert Dunsterville Harvey-Kelly (1891–1917), whose Blériot Experimental (BE 2) had left Dover at 06.45hrs and landed at Amiens at 08.20hrs. By the end of the day Squadrons 2,3 and 4 were in France and No 5 six days later.

As both the seaplanes and aeroplanes were extremely fragile and easily broke up, so their main duties were limited to observing German military and naval movements in order to provide information on exposed flanks and weak points in the German lines. When the pilot was sure that they were over an enemy position and they had been given permission, they were allowed to drop bombs over the side. Very quickly the pilots became highly skilled at spotting troop, train and ship movements, artillery placements, supply depots and harbour modifications. Such that even Haig was forced to admit that aeroplanes were becoming an invaluable asset to the ground forces and seaplanes to naval shipping!

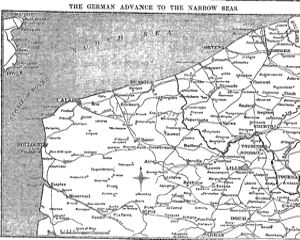

Albeit, the German troops swept through Belgium routing the Belgian army and then defeating the French at Charleroi on 21 August 1914 and two days later the British Expeditionary Force of 90,000 men at Mons. This caused the entire Allied line in Belgium to retreat and the Ostend seaplane base to close. Although the Germans planned to capture the French ports, the Belgians prevented this by flooding the region of the Yser River. By the end of 1914 both sides had established lines extending approximately 800-kilometers (approximately 500 miles) from Switzerland to the North Sea.

Although the initially named submarine base was in the Camber, at the Eastern Dockyard, on completion the Sixth Destroyer Fleet was based there. The general feeling by government was that the problems on the Continent were to be short lived. Peace was expected by Christmas and the seaplanes, aeroplanes and the destroyers would be transferred elsewhere. From then on, just the pre-War military bases would be stationed permanently at Dover. The military were not so optimistic and Brigadier-General Crampton issued a warning notice, through Mayor Farley’s office, to nearly every household in Dover. This notice stated that if the Military order for them to evacuate the town they were to do so IMMEDIATELY.

The first of the German submarines (U-Boats) appeared in the Channel around the middle of September 1914, sinking the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, off Zeebrugge. Immediately after the Admiralty gave notice for a moveable V-shaped boom to be fitted across the Eastern entrance of Dover harbour. This was to prevent U-boats entering but it fitted so badly that it was carried away during a heavy sea, as was its replacement! Blockships were sunk to prevent torpedoes entering the Western entrance and minefields were laid in the Channel between the East Goodwin Lightship and Ostend. The scout ship, Attentive, was attacked by a U-boat on 27 September and this led to the withdrawal of the scouts from patrol duties. They were replaced by the famous Dover Patrol to which the Dover seaplane base and the RNAS No 1, and not long after No 2, aeroplane Squadron at Guston were based. Initially two Wright seaplanes, five Avro 504 seaplanes and two Henri-Farman F20 aeroplanes came on station. All the pilots were armed with either Winchester or Martini-Henri rifles and their own pistols and carried bombs.

At first the town’s only anti-aircraft defence weapon was a single 12-pounder anti-aircraft gun at Langdon Cliff but there were no searchlights. In October 1914, two 6-pounder Hotchkiss quick-firers were placed on the Western Heights. In November 1914, a local Anti-Aircraft Corps was set up by the Admiralty under the command of local General Practitioner Dr Ian Howden supported by a Chief Executive Officer, Lieutenant-Commander Capper. The role of the Corps was to take charge of the new searchlights that were being erected at the Drop Redoubt, Castle Keep and Langdon Battery by the Admiralty much to the annoyance of the Military! On 30 October, Captained by Lambe, the Hermes arrived at Dunkirk having taken seaplanes from Portsmouth. On the following day, off Calais, the German U-27 submarine sank the Hermes. The South East and Chatham Railway Company’s Cross Channel packet Invicta, and two destroyers rescued Commander Lambe and the crew.

Dover Society Plaque – First Aerial Bomb to fall on the United Kingdom.Taswell Stree Christmas Eve 1914. Alan Sencicle

On 21 December 1914 a lone enemy plane flew over Dover and dropped a couple of bombs on the harbour before returning to the Continent. Three days later, 24 December, the weather was cloudy when at just before 11.00hours the first aerial bombing raid in the United Kingdom took place and this was on Dover. The first bomb landed in the garden of Thomas Achee Terson (1843-1936), of Leyburne Road, Dover and had been dropped by Lieutenant Alfred von Prondzynski. He was flying a Taube aeroplane and had been aiming to drop his bomb on the Castle. It fell into a cabbage patch and the blast broke a number of windows in the vicinity and threw the St James Rectory gardener, James Banks, out of a tree in which he was perched cutting holly for Christmas decorations. He was only slightly injured. There is a Dover Society plaque nearby recording the event.

Crew member of a British SS ‘Z’ Class airship about to drop a bomb from rear cockpit of the gondola. Wikimedia Commons

Two British aeroplanes and a seaplane, the pilots armed with pistols, rose in pursuit, but failed to sight their quarry. Fragments of the bomb were mounted on a shield and presented to George V (1910-1936). A man from Bootle, on Merseyside, bought another fragment for £20 at an auction, the proceeds were given to the Red Cross. This was one of the rare occurrences of an aeroplane bombing attack in the early part of the War by the Germans. The German airforce, throughout World War I was made up of the military Luftstreitkräfte and the naval Marine-Fliegerabteilung and they generally preferred the less flimsy Zeppelins that could carry much larger bombs than the hand thrown ones carried by pilots of aeroplanes and seaplanes.

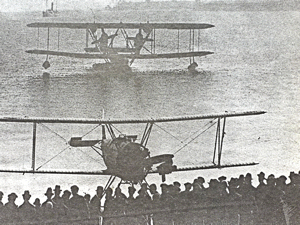

The next day, Christmas day, Royal Naval ships and submarines supported by seven seaplanes, including a significant number from Dover, battled against German Zeppelins, seaplanes and submarines. This was at Cuxhaven on the North Sea coast of Lower Saxony, Germany, some 30miles from the Kiel canal. There, the German surface naval fleet had remained in the harbour throughout the fracas. Nonetheless, this was the first time that the British had used the combination of ships, seaplanes and submarines. Moreover, it was the first time that seaplanes were involved in combat and they demonstrated their capabilities well. During the battle they flew as low as was consistent with safety with the pilots dropping their bombs by hand, over the sides of the cockpits onto targets. It was believed that they did considerable damage including the destruction of a Parseval airship shed and an airship.

On 21 January 1915, German submarines moved into newly erected submarine bases along the coastline they had captured and into the Baltic. The main one for the Channel was at Bruges with outlets at Zeebrugge and Ostend and on 23 January 1915, the Guston aeroplane squadrons used the airfield at Dunkirk to attack German submarines at Zeebrugge. On 12 February, under the direction of Wing Commander Charles Samson (1883-1931), 34 aeroplanes attacked various submarine bases serving the Channel and the North Sea and on 16 February, 48 aeroplanes bombarded Ostend, Middelkerke, Ghuistelles and Zeebrugge, Belgium. Retaliation was various and fierce but on 3 April a German minelayer was driven into Dover harbour while coming under attack from aircraft based in Dover.

Flight Lieutenant Harold Rosher (1893-1916), of No 1 Squadron based at Guston and having flown from the Dunkirk airfield, told his parents of the raid. He wrote, ‘… my orders were to drop all my bombs on Zeebrugge … we went in order … slowest machine first, at two minute intervals … we had four destroyers at intervals across the Channel in case we or our engines went wrong, also seaplanes. It was mighty comforting to see them below.’ Shortly after, the Admiralty decided to make Dunkirk an aeroplane base and future air raids on a large scale would be undertaken from Dunkirk and other bases in France.

About the same time, the Dover seaplane establishment received an Admiralty directive informing them that the role of seaplanes was strictly to support the Dover Patrol by providing observations and intelligence but not combat. Following the directive, the seaplane personnel numbers were reduced and most of the seaplanes were relocated to other bases. The Dover Patrol had been set up by Rear Admiral Hood in order to try and stop German submarines passing down the Channel and into the Irish Sea and the Atlantic, where they were destroying British shipping. Hood’s perceived failure to achieve this goal led to him being replaced as the Commander in Chief of Fortress Dover in April 1915 by Admiral Sir Reginald Hugh Spencer Bacon (1863-1947).

On taking over, Bacon had Guilford Battery demolished and replaced by two sheds. The Dover seaplane station and Guston aerodrome were brought under the Nore Command, which covered all RNAS establishments from Felixstowe to Dover, but remained attached to the Dover Patrol. Flight Commander John Henry Lidderdale (1890-1933) a founder member of the RNAS later retiring as a Squadron Leader, was appointed commanding officer of Dover’s seaplane establishment. Within days, recently qualified personnel arrived along with Sopwith Baby seaplane fighters and ground support personnel. The directive confirmed that they were to work closely with the Dover Patrol but added was the statement to ‘hunt for German machines.’

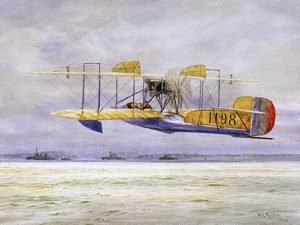

White & Thompson No. 3 flying boat by William Lionel Wyllie 1851-1931. Delivered to Dover September 1915. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

During the summer of 1915, Dover seaplane establishment was equipped with Short Type 830 seaplanes, fitted with bomb emplacements below the fuselage; a Wight Type 840 anti-submarine patrol seaplane and on 14 September 1915, a White & Thompson No3 tractor biplane flying boat fitted with a Lewis gun on the port side of the cockpit for use in anti-submarine patrols. It would also seem that the base acquired a Franco-British Aviation (FBA) Type A and a Wight 171 pusher seaplane and a couple of experimental airships until the airship station was completed at Capel. Supporting the seaplane station was the commandeered and converted as a seaplane carrier, the South East and Chatham Railway packet Riviera

Short type 830 seaplane. Two bomb bays shown below fuselage. William Lionel Wylie. Wikimedia Commons

Guston was supplied with Sopwith Schneider and Martinsyde G.100 aeroplanes with synchronised machine guns that fired through the propeller. The pilots there particularly liked the Sopwith Schneider for night flying, much to the annoyance of locals. The recently qualified seaplane pilots practised over Dover harbour, testing the planes’ capabilities, particularly for speed along the Southern Breakwater. However, on 31 May, a Sopwith Type 830 and pilot had to be rescued from the sea by the crew of the South East and Chatham Railway’s ship Biarritz, which, at the time, had been commandeered for War service.

In early summer 1915, seaplanes accompanied the British Grand Fleet for the first time since the Cuxhaven attack on Christmas Day, nearly five months before. This was an exercise to northern waters to observe the movements of squadrons. Since the Cuxhaven attack, aeroplanes had been tried for this purpose but they had difficulties in rising from the deck of ships at sea. The 14 seaplanes were carried on the former Cunard Liner the Campania that had been gutted and converted by Cammell Laird shipyard, Birkenhead, for the purpose. In the initial trials the seaplanes were lowered into the water using a crane but it was then decided to extend the bow deck by 220feet to create a sort of flight deck and use land planes.

For this the Campania’s front funnel was removed and replaced with two narrower funnels. At the same time, at the request of the Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Jellicoe, the aft deck was cleared and the aft mast remove to enable the ship to carry kite observation balloons. From February 1915 to February 1918, the Campania was under that command of Captain Oliver Swann and it was probably due to his influence that seaplanes were used. They played their first significant role in the Battle of Jutland (31 May-1 June 1916) and continued to do so for the remainder of the War. As for the Campania, she sank on 5 November 1918 following a collision in the Firth of Forth. The wreck site is now classified as being of historical importance under the 1973 Protection of Wrecks Act.

On 10 August 1915 a Zeppelin bombed the harbour near the western entrance killing one sailor and injuring three. Fifteen days later there was another Zeppelin attack on the town but there were no casualties and anti-aircraft guns brought the Zeppelin down. Then on 15 September the first fatal flying accident occurred when Guston based Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Hobbs age 19, was killed near Martin Mill. During his career he had flown between 45 to 50 hours but was flying one of the Martinsyde G.100 aeroplanes for the first time. Flying at least 3,000 feet, all appeared to be well until the plane suddenly circled two or three times, turned over several times then fell to the ground.

Sea Scout (SS) airship, nicknamed ‘Blimps’ powered by BE2 single-engine tractor mount. Dover Transport Museum

Admiral Bacon, on 23 September 1915, welcomed George V and showed the King round Admiralty harbour and other aspects of naval defence. This included the Mote Bulwark seaplane base, the Guston aerodrome and the Capel airship station. There the production of cheap Sea Scout (SS) airships, nicknamed ‘Blimps’ had begun. These, at this time, were powered by the BE2 single-engine tractor mount, with the airscrew mounted in front, pulling the balloon through the air rather than pushing it.

During that day, the prospect of using planes as part of the offensive were discussed with top officials, particularly in the light of the continual attacks by the German Zeppelins, seaplanes and aeroplanes on Channel shipping. Flight Commander Lidderdale stated that Zeppelins had been brought down and that the Dover Patrol preferred seaplanes to aeroplanes for Channel operations. Adding that, all planes were subject to engine failure but if an aeroplane came down over the sea, they sank. Lidderdale went on to say seaplanes had wooden boat like hulls that were planked with mahogany and cedar with steps on the bottom. As the seaplane was pulled along by its propeller it rose onto these steps and skimmed along the water until it took off. If the seaplane came down over water problems could be dealt with at the time, once these had been done the seaplane could take off again. If the trouble was not too serious, then the pilot could possibly get engine going sufficiently well for him to use the seaplane as a powered boat and if not, the seaplane would still stay afloat until help arrived.

Lidderdale was thanked, relocated elsewhere in the country and Wing Captain Commander Charles Lambe replaced Flight Commander Lidderdale. Further, it was stated, the pilots’ of airships based at Capel were better at spotting submarines in the Channel than the pilots of seaplanes. Thus, preference was to be given to expanding Capel, reducing the number of seaplanes at Dover and augmenting both with aeroplanes based at Guston.

During the winter of 1915-1916 the formidable German Fokker monoplane made its appearance showing the full potential of aerial warfare. Fast and manoeuvrable it was fitted with interrupter gear and synchronised gun and airscrew. Throughout January, Dover was under constant attack and this showed the woeful inadequacy of the town’s defences. Further anti-aircraft guns were erected at the Castle and Fort Burgoyne, along with two 6inch guns on the Eastern Arm and the Prince of Wales Pier for the better protection of the harbour. These too, quickly proved to be inadequate and it was quietly recognised that the introduction of the Fokkas had enabled the Germans to acquire a marked superiority in the air. This was not only due to the quality of their machines but resulted from the sheer amount of them and the training of the men who flew them.

Compounding the situation, German seaplanes still remained a major force to be reckoned with. During the moonlit night of 23 January 1916, German seaplanes raided Dover dropping eight bombs that killed one person and injured several others included children, some seriously. At lunchtime the following day, two German seaplanes circled Dover and the pilots dropped bombs on the Marine railway station, Western Heights barracks and the Western Docks. The following day a German airship dropped bombs on the air sheds at Capel and questions were raised in the House of Commons. These centred on the lack of British aircraft to deal with the foe and those that did, only did so when the foes were returning to the Continent.

At the time, Field Marshall Kitchener, was the Secretary of State for War (1914-1916). His office stated that due to economic reasons, the number of seaplane pilots and seaplanes based at Dover had been reduced. Nonetheless, the Commons were told, there was still a large contingency of aeroplanes at Guston and they had seen off the attackers. To this, Canterbury MP Captain Francis Bennett Goldney (1865-1918) said that the previous weekend he had taken a walk to the RNAS Guston airfield and although the mess buildings were functioning, as the airfield had hardly been used since the previous autumn, the farmer was ploughing it up in preparation for crops!

Following Bennet–Goldney’s relentless questioning, the House was told that on the day Dover was attacked, 24 January, the German planes had arrived when the seaplane pilots were at the mess having lunch at Guston, some two miles away. However, there was a seaplane pilot and a couple of ground crew at the Mote Bulwark depot working on a faulty machine when the German planes arrived. Although he had not received permission from the Admiralty and was later in serious trouble, the pilot managed to scramble the seaplane and armed with his pistol, gave chase. At Swingate an aviator also managed to get an aeroplane in the air and armed with a Winchester rifle and five rounds of ammunition, he too gave chase.

Unfortunately, the House, were told, the Swingate pilot mistook the seaplane as German and opened fire and although he did little harm to the British seaplane, the German seaplanes made off. Parliament were also told that although Fortress Dover had been fitted with anti-aircraft guns, for economic reasons they were armed with percussion shells. These, the Members were told, required a high degree of accuracy to be of any use and as the gunners were firing at moving objects, high up in the air, success was only achieved by accident. On the day of the bombardment of Dover, the British gunners’ only significant impact was on Walmer Church tower!

On 24 February 1916, off Dover, the liner Maloja – the largest ship in the P&O fleet and carrying 456 passengers and crew was torpedoed. 155 people drowned in the cold sea but many of the survivors were taken to the Lord Warden Hotel near the Admiralty Pier. The few seaplanes still based in Dover had helped in the operation. The attacks on Dover continued and throughout the raiders were heavily and continuously fired at by the new defence guns, but still without results. The plight was still played down by the Admiralty and War Office but locally an aircraft recognition poster was issued.

In March 1916 a Zeppelin dropped a number of bombs on Whinless Downs and two incendiary bombs at Hougham. Then on the afternoon of Sunday 19 March, two German seaplanes flew over Dover at about 14.00hours and dropped six bombs on the harbour before heading north-west, dropping more bombs on the town. One of these went through the roof of St Vincent Convent in Eastbrook Place, which at the time cared for children and was crowded. Falling tiles injured Sister Vincent but luckily none of the children were hurt. This was the second air-raid attack the Convent had suffered in ten days and subsequently they moved to temporary accommodation in St Leonard’s-on-Sea, East Sussex. In the 19 March attack on Dover, a bomb wrecked the storehouse and stables near St Mary’s Church and another bomb exploded some ten yards away from the Salem Chapel on Biggin Street blowing out the windows of nearby shops. In total, 7 people were killed in the town and many more were injured. Another seaplane dropped several bombs on Deal, while two others attacked Thanet.

Once permission was given, several Dover seaplanes led by Flight-Commander Reginald John Bone (1888-1972), went in pursuit but 30 miles out to sea, after an action lasting 15minutes, they had to give up. Albeit, during this fight a German machine was hit and an observer was killed but in East Kent, a total of 11 civilians were killed of which 5 were children and 28 were injured of which 9 were children.

An enemy airman came over Dover on 25 April, at a height of 6,000feet and circled round, but did not drop any bombs. He was in full view but the warning sirens of an impending attack were not allowed to be sounded until, again, the Admiralty had granted permission. In Dover, the sirens were sounded until 20 minutes after the hostile plane had been spotted and 15 minutes after it was over the town. After which the RNAS planes including the seaplanes had to wait for clearance from the Admiralty before they took off. This meant that unless seaplane pilots took off without permission and thus finding themselves in serious trouble, as had happened in January, the Germans were well on their way back home by the time permission was granted.

In Ramsgate, locals said that the RNAS pilots and their crews were sitting around while raids were taking place. Initially, they were not believed, but on investigation it was found that what they had said was true. The reason given was that RNAS aeroplanes were not allowed to scramble until they too had received orders from the Admiralty. A deputation of Mayors from East Kent, led by Dover’s Mayor 1913-1919, Edwin Farley (1864-1939), tried to see the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French (1852-1925), to rectify matters. However, their efforts were met with procrastination and eventually they were told that Field Marshall French had declined to give orders to change the procedures. Throughout the spring and summer that year, the attacks continued on East Kent and the number of fatalities and injured continued to rise.

On 20 May there was another moonlight raid at 02.15 by two or three German seaplanes that dropped their bombs in rapid succession. On this occasion Dover College, where the boys were in residence had a narrow escape. A bomb fell close to the Grand Shaft Barracks on Western Heights, and one fell on the roof of the Ordnance Inn in Snargate Street, throwing several tons of masonry into the street. Another fell on Commercial Quay but throughout this raid the guns of defence were silent as orders from the Admiralty had not been given. The same happened on 9 July when several bombs fell but luckily they did little damage.

Part 2 of Dover’s Seaplane Base and Mote Bulwark follows on.

A short version of this story was published in the Dover Mercury on 26 October 2014 and a longer version was Uploaded on 8 July 2017. Following a talk given at Dover Museum on the World War I Seaplane base, as part of the Zeebrugge Raid Centenary celebrations, of 21 April 2018, the story was expanded to include a more detail account of Dover and Seaplanes. This was Uploaded to coincide with the Royal Air Force centenary celebrations of July 2018.

For further information:

Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust: http://www.abct.org.uk