Part 1 of Dover’s Seaplane Base and Mote Bulwark started with the foundation of Mote Bulwark, the military site at the base of the Castle cliffs on the east side of Dover bay. This remained in the hands of the military up until a few years before World War I (1914-1918), when the site was given over to leisure activities. However, as the storm clouds of War started to gather, the area was taken over by the Admiralty and a Seaplane base was established. Part I of Mote Bulwark and Dover’s Seaplane base, discussed the development of aviation at that time and the role of the Dover seaplane establishment in the first year and a half of World War I. Part 2 of the story begins at this point.

1. Dover Seaplane base from the summer of 1916

In the early summer of 1916, Field Marshall Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) was the Secretary of State for War (1914-1916) and he was looking to close Dover’s seaplane base. Dover at the time was under military rule and officially called Fortress Dover with Admiral Reginald Bacon (1863-1947) in command. In 1912, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) formed and was made up of both military and naval personnel. On 1 July 1914 the naval wing became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) while on 1 August 1915 the RFC, that had remained as the military wing, was officially separated from the army. The Seaplane station was part of the RNAS and at Guston was its sister establishment, the RNAS aeroplane base.

Lord Kitchener was killed on 5 July 1916, while on board the Hampshire when the ship struck a mine off Orkney. The next day David Lloyd George (1863-1945) was appointed Secretary of State for War, a post he held until the end of the year when he was appointed Prime Minister. Admiral Bacon used the opportunity and wrote to Lloyd George reiterating previous correspondence and emphasising the role of the Dover seaplanes within the context of the Dover Patrol. ‘Pilots’, he wrote, ‘were able to recognise sections of coastline from great heights and distances at the same time familiar with the different kinds of seagoing craft.’

Bacon followed this with a number of requests, including more seaplane and aeroplane pilots based at Dover; as well as increasing the number of naval personal training as pilots. In support, specially trained gun crews on both types of planes and the increase in the numbers of ground crew. Finally for the provision of more effective seaplanes. He was particularly interested in the Handley Page Type O, later nicknamed the bomb-dropper. This was a large, unequal-span three-bay biplane that was surprisingly light, as the spruce fuselage and flying surfaces, where possible were hollow. The four-bladed propellers, rotated in opposite directions to cancel torque and the four engines were enclosed metal nacelles. This was agreed with 7A Squadron of the newly formed 5th Wing RNAS coming to Guston before being based at Dunkirk. However, not long after a Handley Page Type O one was captured by the Germans and they adapted the design to what became the Gotha three-seater. Like the Handley Page aircraft, they carried about one-third of a ton of bombs the size of which was about 110lbs each. The shape of the bombs were designed so that they fell straight down and with increasing speed affording them more penetrative power.

The No 5 Wing together with members of the newly formed No 6 Squadron came to Guston before being sent to France. At the same time at the Seaplane base, the much better Short Type 184 machines replaced the Short Type 830 seaplanes. These were two-seater aircraft that not only increased the efficiency of reconnaissance and bombing, but could also carry 14inch torpedoes. At the same time a few Fairey Hamble Baby single-seater naval patrol aircraft were brought on station. Then, towards the end of 1916 the seaplane base was supplied with more Short Type 184’s and also Wight Type 840 anti-submarine patrol seaplanes.

Shortly after Coastal batteries and patrol boats were given authority to take defensive action without clearance from Admiralty HQ! Although, under difficult circumstances of inadequate searchlights and armaments but with a strength of 137 volunteers, the Dover Anti-Aircraft Corps, which operated every night for nearly two years, were stood down. The air defences were totally reorganised and manned by military personnel and new stations were also erected but well outside the Dover boundary. At the harbour, the Admiralty had two 6-inch, anti-aircraft guns placed on the Prince of Wales Pier and the Eastern Arm respectively. Although they could not fire at a great angle their presence, it was believed, would act as a deterrent! The guns remained until after the May raids of 1918, when they were both removed.

World War I Zeppelin brought down August 1915 by Dover Anti-Aircraft guns courtesy of Doyle collection

Later in the summer of 1916, the seaplane personnel, sanctioned by Bacon, started making modifications to the Short Type 184 seaplanes. These improvements were such that the Admiralty renamed them Dover Type Short and ensured that the modifications were incorporated into Short Type 184 based elsewhere. These modifications included the introduction of uprated Sunbeam engines and a modified radiator, designed by Flight Lieutenant Charles Teverill Freeman (1894-1967). In October 1916 the Flight Lieutenant was awarded the Distinguish Service Cross in recognition of his gallantry and skill on the night of 2 August when he made a determined attack on a Zeppelin at sea. Returning a second and a third time, Freeman only abandoned his attack when he had exhausted his ammunition.

Freeman was one of the many seaplane pilots that spent time at the Dover base, others included Charles Langston Scott (1891-1972) who had been stationed at Dover before being assigned to command the Flying Boat Development Flight at the Royal Naval Air Station, Felixstowe. Before leaving Dover he had suggested to Bacon’s predecessor, Rear Admiral Horace Hood (1870-1916), the use of flying boats at Dover. Scott was subsequently promoted to Wing Commander and in 1931 was in charge of an experimental flight from England to Egypt. In November 1916, after Scott had left for Felixstowe, eighteen-year-old Adrian Henry Paull (1898-1965) entered the RNAS. Two months later he was appointed Flotilla Squadron Leader aboard the Lightfoot, a Marksman-class flotilla leader destroyer and was seconded from Harwich to the Dover Patrol in charge of a seaplane squadron made up of 23.

At Capel, again sanctioned by Bacon, the engineering section had built a successful variant of the SS Airship, with an improved car and a 75 horsepower Rolls Royce Hawk aeroengine. In a test flight it had been shown that the airship was capable of flying at over 50mph and was capable of carrying bombs weighing 350lbs. However, the modifications did not please Kitchener but following his death Bacon brought the modifications to the attention of Lloyd George. In August 1916, the Secretary of State for War supported by a retinue of personnel from the Admiralty came to Capel to watch a test flight. The modifications were then incorporated and also into the production of Sea Scouts as SSZero’s.

The air raids on Dover by the German airforce continued. This was made up of the military Luftstreitkräfte and the naval Marine-Fliegerabteilung. Albeit, on the night of 2-3 August 1916, a Zeppelin endeavoured to approach Dover when it was driven off by heavy gunfire. On 12 August, at 12.25hours, two seaplanes dropped four bombs from a height of 7,000feet to 8,000feet. One fell on the harbour and another caused slight injuries to some soldiers on parade at Fort Burgoyne. Thirteen days later, on 25 August a Zeppelin approached Dover from the west but was forced by gunfire to turn south and emptied its bombs into the sea off Shakespeare Cliff. On 22 September a seaplane, which remained in view for eight minutes, dropped bombs near the Duke of York’s school but caused no casualties.

In the Channel, regardless of the efforts of the Dover Patrol, both Royal Navy and merchant ships were succumbing to torpedo attacks from German destroyers and U-boats. During the nights of January and February 1917 German destroyers and U-boats shelled, Dover, Southwold, Broadstairs, Margate, Ramsgate and Dunkirk. Each time, the vessels returned to their bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend undamaged. The German press made great play on the supposed British naval superiority, especially as the British fleet were being decimated. In the air, there was not a great deal of success and the bombing by the German combined airforce continued.

On 17 March 1917 a Zeppelin came towards Dover from the direction of Canterbury, and dropped an enormous bomb, reputed to have weighed 600lbs on Whinless Down, in a corner of Long Wood, Elms Vale. This was the largest bomb dropped in the district during the War. The Zeppelin also dropped two other bombs near Hougham, and then made off over the sea. She was brought down in France later that day. On the same day an aeroplane dropped several bombs near Langdon Battery and in the Camber. Following the raid, the German press falsely claimed that Dover Gas Works had been destroyed along with Swingate aerodrome. From October 1916 the British military Swingate aerodrome, to the east of the Castle and on the seaside of the Dover-Deal (A258) road, was mainly involved in training. At the time of the supposed attack the men were preparing the site for new occupants. On 6 April 1917, the United States of America declared war on Germany and the USAir Force took over Swingate.

When the German press reported that one of their seaplane squadrons had successfully bombed British vessels lying in the Downs, off Deal, and searchlights at Ramsgate, Reuter’s news agency negated the story. Based in London, the highly respected news agency reported that a single hostile plane had passed over some of Kent’s coastal towns dropping eight bombs but most had exploded on open ground. In fact on 19 April, the monitor Marechant Ney, while anchored in the Downs was attacked by a German seaplane that had swooped down very low and released a torpedo. This, missed the target and was brought down in the mud outside Ramsgate Harbour.

It was noted by the Royal Navy that the German press had not reported that on 7 April the sea wall at Zeebrugge, or the Mole as it was correctly called, was bombed by Dover RNAS seaplanes and aeroplanes. The contingency had also bombed ammunition dumps in Ghent and Brussels. At the same time G.88, a large German destroyer in Zeebrugge harbour, was torpedoed and sunk by the Dover based Coastal Motor Boats. Taking part in the RNAS attacks were large Curtiss H.12 Flying boats based at Dover. These had been sent to Dover on loan as a try out following the recommendation of Scott. He recommended for them to be tried out undertaking the same kind of work as seaplanes with the advantage of greater power and endurance in bad weather. The main problem was hoisting them onto dry land so they were kept at sea in the harbour, when not in use.

On Friday 25 May 1917, the Germans sent a squadron of about 16 Gotha bomber aeroplanes to attack East Kent. This was part of a German Gotha campaign that was to last until April 1918 and usually operated on a patrol line that stretched from Throwley, south of Faversham through Bekesbourne to Dover. During this period there were 113 air-raid alarms and the town was bombarded with 185 bombs and 23 shells. The number of civilians killed was 23 and 71 were injured. On that Friday, 25 May, the Gotha bombers travelled further afield. Using the Thames for navigation, they were intent of extending the attacks to Essex airfields. However, due to heavy cloud on reaching the Thames they turned south and at about 18.20hours the sky cleared when the squadron was just north of Folkestone. They dropped their loads over the town but no sirens were sounded. Tontine Street, which received the brunt of the attack, was crowded with shoppers. The British official response, initially, was to deny that the raid took place even though it was known that the casualty rate was high. When this became public knowledge, there was a blanket refusal to disclose the names of the victims.

Captain Alan Hughes Burgoyne (1881-1927) the Conservative Member of Parliament for Kensington brought this to the attention of the House of Commons. He asked, amongst other things, why had neither Folkestone nor Dover been warned of a possible impending attack. Further, why although many seaplanes lay ready for instant service in Dover harbour, orders to scramble were not given until 20minutes after the attack had taken place. Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French (1852-1925) responded by saying that it was not possible to prevent attacks by aeroplanes, but that one of the Dover aeroplanes had shot down one of the German planes. Further, ‘he hoped that the measures that had already been taken would make any future raid a risky operation.’ East Kent had already found to their cost that Lord French tended to contradict orders that changed accepted procedures. However, in the light of the Folkestone attack, procedures were changed.

The response from the Germans was to say that the attack was on Dover harbour and that most of the naval and military ships and machinery had been destroyed and personnel had been killed. Their report went on to say that the British had fabricated the story that it was an attack on an unprotected South coast town and that the casualties were civilians to turn international feeling against the Germans. Following this communiqué, the Government agreed to make it officially known that the raid took place over Folkestone and that 71 civilians – 16 men, 28 women and 27 children – had been killed, while those injured amounted to more than 94. Still under attack by the German propaganda machine supported by news agencies in the UK, the British government eventually allowed the publication of the names of those who had been killed in the attack.

On 5 June 1917, monitors of the Dover Patrol carried out a bombardment of the German occupied port of Ostend. The Harwich Force, including the Lightfoot, patrolled to the North East of Ostend to screen the bombarding force from attack. Taking part were seaplanes and flying boats under the command of the Lightfoot’s Flotilla Squadron Leader Paull, still on secondment to the Dover Patrol. Although no longer having to await Admiralty permission to meet hostile planes until after they arrived, the problem of not knowing when they were coming remained. Thus the bombing continued.

In July 1915, a 16-foot sound mirror had been cut into the chalk face by Professor Thomas Mather (bc1856-1937) of the City & Guilds Engineering College, London working at Binbury Castle near Maidstone, Kent. He claimed that it could detect aircraft from 20 miles away. The sound mirror was hemispherical with a sound collector mounted on a pivot at the focal point. The sound collector was a trumpet shaped cone and the listener, who wore a stethoscope, moved the sound collector across the face of the mirror listening with his stethoscope. When he found the point where the sound was loudest bearings were taken and were read from vertical and horizontal scales on the collector. In 1917 these Sound Mirrors were being constructed along the south and east coast and the Thames estuary. The one in Fan Bay, below Swingate and another at Abbots Cliff can still be seen.

No 212 Squadron had been formed at Dover in June 1917, and large Felixstowe F2 flying boats were brought on station to augment the existing fleet. These were designed and developed by Lieutenant-Commander John Cyril Porte (1884-1919) at the Royal Naval Air Station Felixstowe and were fitted with two 350 horsepower Rolls Royce engines. Soon after arrival hydrophones were introduced that would allow the occupants of these flying boats, while ‘sitting’ on water, to listen for U-boats. To accommodate the F2s the Boundary Groyne was adapted to catapult the F2’s into the air and the launchway – the official name given at the time – consisted of two long shallow wooden channels to house the aircraft’s floats. The launchways were well greased and as the seaplane was prepared for take off, ground personnel held it down until the engine was opened up. As they let go, the flying boat was described as ‘leaping’ off the end of the launchway and into the air but sometimes into the sea! A concrete slipway was laid on the eastern side of the launchway and two more hangars were erected. A motor-powered winch for hauling the planes from the sea was housed in each hangar and thick wires, running over pulleys, hauled the flying boat onto a cradle and up the slipway.

At about the same time De Havilland DH9 and 9a together with Sopwith 2FI Camel naval fighters arrived and were based at the Guston airfield Wing Commander (later Air Vice Marshall) Charles Laverock Lambe (1875-1953), on 10 June 1917, had written to the Admiralty saying that British seaplanes had poor armaments and were inferior in performance compared to the German machines. The German heavily armed fighter seaplanes based at Ostend and Zeebrugge, he wrote, could attack the British slow-flying seaplanes while protecting their own fighter seaplanes. Although he recognised that aircraft sank if shot down over the sea, he recommended that with the exception of a few seaplanes kept back for reconnaissance purposes, they should all be withdrawn. He finished by recommending that they were replaced with aircraft fitted with airbags in the fuselage.

By August 1917, sirens alerted locals some 10minutes before enemy seaplanes and aeroplanes arrived and naval and military personnel were alerted before if possible.

On 22 August a group of seven or eight Gothas in squadron formation came over the town at a height of from 11.000 to 12,000feet and dropped a dozen bombs. Most of these fell into the Harbour but one bomb dropped in the yard of the Admiral Harvey Pub in Bridge Street. Another fell in the grounds of Dover College, near a party of reservists in training, killing two and wounding three others. One fell on a house in Folkestone Road and passed through the floors without exploding. By the time the German aircraft arrived the Dover seaplanes were already in the air and along with coastal defence artillery, they fought off the invaders and two enemy aircraft were brought down. This was the last of the daylight Gotha raids.

Then on 2 September a single Gotha dropped seven bombs at 23.00hours – this was the first of the Gotha moonlight raids. Three fell in rapid succession and created unusually large craters. One fell near Castlemount that had been requisitioned as a Hospital, on the east side of Dover and two others just missed houses. Before the War Castlemount was a teacher training college operated by the French Les Frères des Ecoles Chrétiennes monks and opened in 1911. Following the War, the monks returned and stayed until 1939. One man was killed and four women and two children were injured, including one woman who was blown bodily out of her cottage. This was followed by an attack that was reported as coming in waves, lasting twenty to thirty minutes with the bombs causing a great deal of structural damage and injuries.

Almost immediately after dusk, on Monday 24 September 1917, the drone of Gotha bomber aeroplanes could be heard approaching and bomb dropping commenced as soon as Martin Mill was reached. The plane followed the Dover-Deal railway line into Dover, dropping bombs at intervals on the track. Another Gotha approached Dover from the sea and it’s first bomb fell in the passage leading from Castle Street to Dolphin Lane, but did little damage. The next bomb fell on the Wesley Hall in Folkestone Road where it hit the apex of the northern end wall blowing it away. The result was that the roof slipped off either side of the building and the crossbeams fell inside. Luckily no one was in the building.

The next bomb fell in the front garden of 10 Folkestone Road, occupied by J B Smith, some five or six yards away from the windows. In one of the front rooms Miss Pilcher was conducting a shorthand class, at which there were six young ladies present. When the bomb fell they were all injured, and one of them, Dorothy Eleanor Wood (1900-1917), subsequently died of her injuries. Miss Pilcher sustained a fractured thigh and Winifred Mary Greenland (b1902) lost an eye. The next bomb fell on the rear of 55 Folkestone Road where it fell on a garden wall, and its concussion did a great deal of damage to the adjoining houses. Another fell in the front garden of 57 Folkestone Road, but did not explode. Another bomb fell on the top of the railway entrance tunnel under the Western Heights. A bomb hit the back of 3 Selbourne Terrace, demolishing the detached wing of the house where the occupants had a narrow escape and an incendiary bomb fell on the allotment grounds at the back of Clarendon Place. A bomb was dropped on 40 Glenfield Road and the back of the house was blown in. Annie Keates (1865-1917), who had gone to reside at this house, after her own house in Wood Street had been damaged in a previous raid, was killed and her daughter, Annie Evelyn Keates (1905-1917), was so seriously injured that she died at the Hospital. Two houses were demolished in Pioneer Road, luckily the occupants were out. Another bomb demolished 75 Crabble Hill where Ellen Maria Kenward (1862-1917) was killed and buried in the ruins. Her father, Edward Kenward, (1840-1917) was pinned beneath the debris and later died at the hospital. The bedridden lady next door, Jane Gould (1831-1917), died later as a result of shock and injuries.

Over the following ten nights a succession of attacks were made. However, knowing that enemy planes were en route meant the artillery barrage ensured that the damage was not exacerbated. At the same time, Dover seaplanes were being used extensively in action over the Channel and Belgium but both seaplanes and aeroplanes were lost. One casualty was Flight Sub-Lieutenant Cecil Barnaby Cook, age 19 who crashed as tried to land back at Guston. Before his untimely death he had flown seven different types of aircraft since arriving in Dover.

In December that year, Lambe reiterated his recommendations that aeroplanes were superior to seaplanes, suggesting the total abolition of seaplanes for anti-submarine patrols. He did, however suggest keeping the Short Type 184s for communication and short patrol work only. A few weeks before, on 31 October 1917, a Gotha bomber dropped incendiaries along the length of the seafront and the seaplane sheds were set alight. Following the attack, Lambe strongly recommended the closure of the base but when Bacon refused, suggested just retaining a skeleton crew of ground staff to undertake repairs of seaplanes landing in Dover. Again, Bacon, did not agree and the base was quickly repaired.

Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes (1872-1945) appointed Commander in Chief of Fortress Dover on 31 December 1917

Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes (1872-1945) replaced Admiral Bacon on 31 December 1917. Captain Lambe, at the first meeting, was quick to express his delight and views that aeroplanes were superior to seaplanes. He particularly emphasised that Bristol F.2, a two-seat biplane fighter and reconnaissance aircraft made by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, some of which were based at Guston, were proving particularly successful against the German moonlight raids. Keyes accepted Lambe’s point of view but added that he concurred with Admiral Bacon over the importance of seaplanes, saying that ‘the daily round and the common task of the Dover Patrol was the coastal patrol kept up from dawn to dusk, through all seasons of the year, by the seaplanes, only intermitted because of fog or gale. But for this persistent anti-submarine patrol, of which very few people have heard of, the losses of British shipping would be far more serious, for hostile submarines are bound to keep well under the surface for fear of detection, and shipping is thus able to pass by in comparative safety.’

WWI Bristol F.2 two-seat fighter and reconnaissance biplane favoured by Lambe over seaplanes. Wikimedia

Keyes went on to say that the day to day work of the seaplanes involved two kinds of anti-submarine patrols, intensive and extensive. The intensive kind was concerned with spotting and escorting in the Channel. This was the area extending from the coast to a line marked by a number of buoys ten miles out. It was within this section that British and friendly convoys travelled and the older single-seater seaplanes in pairs, worked to protect them. Further out, Keyes said, often to beyond the 30-mile line the newer, faster seaplanes that could cope with heavy weather operated. In an emergency they could react swiftly as combat machines and if brought down, stay afloat. Even further away from the coast of England, the airships from Capel operated and flying boats when they came on station. The Channel, Keyes, finished, was therefore patrolled by every form of seaplane showing that they are essential for the defence of the country.

On 16 February 1918 seaplanes stationed at Dover were escorting a number of British ships crossing the Channel to Rotterdam when 16 German planes attacked the convoy. An air battle ensued and according to the Germans one of the seaplanes was brought down. According to Keyes, a seaplane pilot in a single-seater Fairey Hamble Baby, was in a fight against two of the hostile aeroplanes when his right arm was hit twice causing it to haemorrhage. Holding his arm tightly above the damaged artery, with his good hand, the pilot held the stick between his knees and safely navigated and landed the seaplane in Dover harbour. An Admiralty statement reported that none of the ships in the convoy were hit and that the seaplane patrol reformed and immediately returned to base.

By this time more fighter aeroplanes were based at Guston to escort and defend the seaplanes and flying boats that had arrived. These included the Pemberton Billing designed PB29 Zeppelin Destroyer that was test flown. Although the pilots said it climbed like a rocket it was difficult on take off and landing and therefore never went into production. Following the fracas of 16 February, the German’s were quick to respond with reprisals and over the next four nights, commentators wrote, were the most anxious for Dovorians throughout the War. During the night of Saturday 17 February, twenty-three bombs, all one hundred weight (112 pounds) each, rained on St Margaret’s Bay, to the east of Dover, in a line from Corner Cottage on the cliffs to the sports field near the village. The French Convent of the Annunciade or the Blessed Virgin Mary, founded in 1904, suffered severely as did a number of residences. Both aeroplanes and seaplanes planes went up to meet the attackers and together with anti-aircraft fire, the enemy flew off with one machine falling into the sea off Dover.

On 1 April 1918 the Royal Air Force (RAF) was formed by the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. Keyes called these combined forces at Fortress Dover the Dover Patrol Air Force and he used them to great effect. By this time access and egress to Dover had been tightened up and speculation was afoot that a major sea offensive was about to take place. This seemed to be verified on the 11 April when Royal Navy monitors left the harbour and bombarded Zeebrugge and Ostend harbours. Throughout the War U-boats, based at Bruge with outlets to the sea at Zeebrugge and Ostend, had kept up a constant attack on British shipping and the 11 April counter attack was generally assumed to be the major British offensive on the Continental ports.

That day Dover seaplanes and aeroplanes also dropped bombs onto the one and a half mile sea wall, or Mole, that protected Zeebrugge harbour from the North Sea. Following the raid of 7 April 1917 the Germans had erected a fearsome array of mounted artillery to protect the harbour from attack. After the attack, planes from both bases flew over Zeebrugge harbour to assess the damage, the repairs that were taking place and what additional defence measures were being taken.

Sunday 21 April, at just before 11.00hours the most successful fighter pilot in the War was killed. Lieutenant Manfred von Richthofen (1892-1918), better known as the ‘Red Baron’, was shot down in a dogfight and his death was seen as a good omen by many of the airmen involved in the Zeebrugge Raid. This was near Vaux-sur-Somme and Richthofen was flying a red Fokker triplane over Morlancourt Ridge. He was pursuing Canadian pilot Lieutenant Wilfrid Reid ‘Wop’ May (1896-1952) of RAF No 209 squadron flying a Sopwith Camel. Between 16 February and 20 March 1918, the Squadron had been based at Dover’s Guston aerodrome. Canadian Captain Arthur Roy Brown (1893-1944) attempting to come to May’s rescue, at high speed, dived steeply and then climbed before going in for attack. Richthofen turned to avoid Brown when he was hit by a single .303 bullet penetrating his heart and lungs. Richthofen managed to make a rough landing before dying. Who actually fired that bullet is still the subject of debate and speculation.

Holy Trinity Church Strond Street Pier District 1835, where the Church Service was held prior to the Zeebrugge Raid of 22&23 April 1918. Lynn Candace Sencicle

Monday 22 April, was a lovely day with blue sky, light winds and spring flowers everywhere, it was the day the famous raid on Zeebrugge began. In the morning a special service was held at Holy Trinity Church in the Pier District attended by Keyes, other senior officials and members of the Dover Patrol. While this was going on seaplanes left the base on the seafront and aeroplanes from No 6 Squadron based at Guston joined them as they headed for Zeebrugge.

Zeebrugge Harbour following the raid of 22-23 April 1918, showing the sunken ships,blocking the entrance. Doyle Collection

The marine flotilla set off at 16.00hours on 22 April and included destroyers, submarines, motor launches, coastal motorboats, two commandeered Mersey ferries with three commandeered ships filled with concrete in tow. Heading the convoy was Keyes on his flagship Warwick. Escorting the convoy were Dover seaplanes and Sopwith Camel fighters. The attack on Zeebrugge was in order to block the canal from the U-boat base at Bruge to the port using the concrete filled ships. The attack lasted all night and the following day – which was St George’s Day and succeeded in blocking the harbour mouth and the canal to Bruge. The Zeebrugge raid is still annually celebrated in Dover on 23 April – St George’s Day, the Patron Saint of England. In St James Cemetery on Copt Hill, off Old Charlton Road, there is a section dedicated to those in the armed services that lost their lives in World War I along with a memorial to Vice-Admiral Keyes. There are also Dover Society Plaques on the outside of the Maison Dieu, on Biggin Street and the exterior wall of the museum, in the Market Square, telling of the event.

9 May saw the second part of the mission, to seal off the canal from Bruge at Ostend. From the weather to the nuances of the strategy everything was the same as the Zeebrugge raid. Again the Dover seaplanes and aeroplanes were involved in the preliminary operations, then escorting the flotilla across the Channel and during the raid dropping bombs on gun emplacements. However, the raid was not so successful, primarily due to only one blockship being sunk and therefore not totally blocking the canal entrance. Albeit, the damaged done did inhibit the German’s use of the Bruge base and the port as a destroyer base. Further, due to the overall effect of the Zeebrugge and Ostend raids on the German’s, this was to make that part of the Channel coast useless to them and they withdrew their marine operations.

The German reaction to both attacks was predictable and major attacks on Southern England took place over the next ten days. On the final day, Whit-Sunday, 19 May 1918, the Germans lost seven machines, two of which were brought down in the sea off Dover. In one the body of a flight commander was found, wearing the Order of Merit. Another German machine was brought down in flames near Canterbury. From then on, the Germans almost left England alone but increased their fury on Calais and Boulogne. There they flew down the Channel and on turning towards the town selected, they heavily bombed it.

The Dover Patrol Airforce, which included the Dunkirk base, turned their attention to the Continent, where they repeatedly, at low altitudes, bombed aerodromes from which the German aeroplanes set out to bomb England. In Command at Dunkirk was Geoffrey Rhodes Bromet (1891-1983) who had gained his early experience flying seaplanes in Dover and rose to the rank of Air Vice Marshal. Later, he was appointed the Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Man 1945-1953. Meanwhile, over the Channel seaplanes and flying boats attacked U-boats while the aeroplanes based at Guston chased after and attacked Zeppelins.

On 21 March 1918, following the surrender of the Russians 18 days before, the Germans started their Spring Offensive (March-July 1918) under General Erich von Ludendorff (1865-1937). This was to try and break through the Allied lines from the Somme to the Channel and from early April their objective was to force the British and Allies back to the Channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk and out of the War. Captain Lambe was promoted to Colonel and temporary Brigadier General of the Royal Air Force and sent to France.

The ensuing Fourth Battle of Ypres (7-29 April), was bloody with an estimated 86,000 German, 82,040 British, 30,000 French and 7,000 Portuguese casualties. The War was still raging and it looked, as if Ludendorff’s objectives were being achieved, albeit, there was a perceptible running down of the Dover seaplane base. It was hoped in Dover that the President of the new Air Board, Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray (1856-1917), who had strong connections with the town – his company had built the Admiralty Harbour – would recognise the need to keep the Dover Seaplane Base.

On the Continent Ludendorff introduced a new tactic and was advancing, deeply penetrating the British lines. On 8 August the Allies launched their counter offensive with the introduction of strategic blanket bombing of German industrial targets, under the responsibility of Sir Hugh Trenchard (1873-1956). At the same time low flying aircraft were to be used to drown out the sound of tanks as they moved forward at night and at first light the RAF launched low-flying, pre-emptive attacks on German airfields and shipping. During this time, the RAF destroyed more than 8.000 enemy aircraft, dropped 8,000tons of bombs and fired 12million rounds of ammunition at ground targets.

Trenchard’s work had previously impressed the Commander in Chief, Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), for which he was knighted and appointed the Chief of Air Staff in January 1918. His vision for the RAF was as a separate senior service in its own right. Admiral of the Fleet, David Richard Beatty (1871-1936), on the other hand, saw the fledgling RAF in a supportive role to the other two services. Further, he had the backing of Harold Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere (1868-1940), the then President of the Air Council (1917-1918), along with cabinet ministers, the military and senior naval officers, In March 1918, Trenchard resigned after a difference of opinion with Lord Rothermere but was re-appointed by the newly appointed President of the Air Council, William Douglas Weir, 1st Viscount Weir (1877-1959). This had led to Trenchard playing a leading role in the blanket bombing of German industrial targets, a strategy that was to be used again in World War II (1939-1945). On gaining the appointment Trenchard based his headquarters in France and under his leadership, proved that the RAF had the capability to be a senior armed service in its own right.

The War was rapidly moving towards its final days on 1 July 1918, when the order came that Dover’s seaplane base was to close. In less than a month, on 20 July, at 09.25 hours, the sirens in Dover sounded and a German machine flew over the town from the direction of St Margaret’s Bay. The Seaplanes went up to fight it off and at the same time, the plane was heavily fired upon from the ground. Faced with this combined barrage, it turned away towards Ostend without dropping anything. That was the last air raid on England and given as the justification for running down of the Seaplane Base except for keeping the token number of four Short 184s and support staff. Thereafter, there was only one more air raid warning given at Dover, this was to announce the end of the War at 11.00hours on 11 November 1918 – Armistice Day.

The Marine Parade Seaplane base officially closed in March 1919 and the remaining staff had a farewell dinner.

From when the RAF was formed on 1 April 1918 to 31 October 1918 in UK anti-submarine patrols in Home waters was:

Total number of hours flown: 39,102

Hostile submarines sighted: 216

Hostile submarines attacked: 189

Hostile aircraft attacked: 351

Hostile aircraft destroyed: 184

Hostile aircraft damaged: 151

Hostile mines spotted: 69

Hostile mines destroyed by aircraft: 32

Total number of bombs dropped: 15,313 – This was equal to 666.5tons

Total Convoy fights: 3,441

Total photographs taken: 3,440

Map of Dover showing the number and where the town was bombed and shelled in World War I and the number of fatalities and injuries. Dover Library

The number of Raids during World War I on Dover

Were: 113

Bombs dropped: 185

Shells on the town: 23

The civilian casualties:

Killed:

Men: 13

Women: 7

Children: 3

Injured

Men: 36

Women: 23

Children: 12

Throughout World War I and for some weeks after the Armistice was signed the town remained Fortress Dover under military rule. Strict regulations still applied including publicity and in consequence, a hundred years later, other towns which played a much lesser role in the defence of the country can, and have, made tourist capital with respect to their roles. So successful have they been that during the centenary coverage of World War I in 2014, Dover – one of the key players in the defence of nation – was ignored by Royalty, Parliament and the mainstream media such as the British Broadcasting Company – the BBC!

Although the nation in 2014 chose to ignore Dover’s pivotal role during World War I, back in Post-World War I Britain, society’s attitude was very different. The country collected the money to pay for a memorial to the Dover Patrol, of which the Squadrons that flew and maintained the Dover seaplanes, aeroplanes and airships based at Mote Bulwark, Guston and Capel. Many of the pilots that had been based at Dover, Guston and Capel were highly decorated but a great many more lost their lives during the conflict. Hence, they were part of those honoured on 27 July 1921, when the Dover Patrol Memorial Obelisk was unveiled by Edward Prince of Wales (1894-1972) on Leathercote Point, St Margaret’s Bay. Shortly after a second Memorial Obelisk was unveiled at Cap Blanc Nez and a third at New York harbour in memory of the Dover Patrol’s French and American comrades. In 2015, the Dover Patrol Memorial at St Margaret’s Bay was given Grade II Listed Status.

InterWar Developments

The Air Ministry was created on 10 January 1919 to manage the Royal Air Force and the Secretary of State was Winston Churchill (1874-1965). He re-appointed Trenchard as the Chief of Air Staff on 31 March whose main job was the demobilisation of the RAF and establishing the service on a peace time basis. However, before Trenchard took up post, on 26 March, under Air Commodore Charles Lambe, the aeroplane squadrons at Guston were moved to Hawkshill aerodrome, Walmer and the Dover Seaplane base was formally closed. Once in office, Trenchard re-opened the Dover Seaplane file and following a debate in Parliament the decision was reversed as it was agreed to keep a token number of RAF ground crew there. All but one of the hangars was removed and the launchways and slipways were buried. Renamed the Marine Aircraft Repair Depot, the establishment’s role was to refuel and undertake emergency repairs on RAF seaplanes or flying boats that landed in the harbour.

At Folkestone, during March 1919, arrangements were made for the introduction of flying trips in seaplanes, as a tourist attraction. These machines were designed to carry four passengers in addition to the pilot and Jacob Pleydell-Bouverie, 6th Earl of Radnor (1868-1930) made the first flight. However, the Air Ministry quickly reminded the company that civilian flying was not allowed. On 1 May 1919, this was reversed and the Air Ministry issued the first official post-war rules and regulations. On 5 May the Government advertised the sale of former World War I aircraft. On the list were a number of seaplanes that had been based at Dover and these included the last four of Dover’s Short 184s. Former pilots set up flying companies, bought these planes and a number contacted Dover Corporation with a view to using the harbour as a seaplane terminal. They stated that their companies would be offering flights to places within Britain and also Europe.

Although the War was over, the harbour was still in the hands of the Admiralty so in 1919, neither Dover Harbour Board (DHB) nor Dover Corporation had the authority to give permission. Nonetheless, both the Corporation and DHB were keen on the idea and suggested that aircraft companies made their own applications to the Air Ministry, adding that they would endorse such proposals. The Admiralty declined and the aviators went elsewhere. On 9 September 1923, by Act of Parliament, the Admiralty Harbour was transferred to DHB and British seaplane companies were contacted but the country was in a recession that was getting worse and there was no viable response.

The pre-War Territorial Army Drill Hall at Mote Bulwark that became the County Skating rink before commandeered by the Royal Navy for the WWI Seaplane service. Following the end of the War, it reverted to its original purpose as a Territorial Army Drill Hall. Hollingsbee Collection

About this time, the RAF initiated an air service between London and Paris. The Post Office, in early 1919, had opened an airmail service to and from Cologne, Germany. They opened a second airmail service to Cairo, Egypt and onto Baghdad, Iraq in 1922. Over the following decade the RAF pioneered all the major air-routes to what was then British Empire Countries (formalised in 1931 as the Commonwealth of Nations), using both aeroplanes and seaplanes. Once it was realised that private enterprise was not interested in setting up a seaplane base at Dover, DHB jointly with the Corporation approached the Post Office to persuade them to set up a seaplane operation between Dover and the Continent. They, however, were not interested. By this time, what was left of the former seaplane buildings at Mote Bulwark had been converted into army married quarters and the one remaining hangar housed a military riding school. The former skating rink building reverted to its original use as the Territorial Army Drill Hall.

It was not until 1928 that seaplanes returned to Dover’s harbour when French Henri Balleyguier’s (1887-1969) Compagnie Aérienne Française set up the Channel Air Express. This started out as a seaplane taxi service between Dover and Calais. DHB were so keen on the idea they designated a seaplane anchorage east of the Prince of Wales Pier with landing runs of 1,000, 1,200, 1,600 and 1,800 yards. The service quickly proved popular with journeys taking 20-minutes to Calais but passengers, on boarding the plane from the Pier, were almost guaranteed a wetting! However, the possibility of the rapid transhipment of mails was not lost on the French railways and this was soon after, put into operation using the Channel Air Express.

So successful was the Channel Air Express that Dover was designated as one of England’s eight official airports and only one of two for seaplanes – the other was at Woolston, Southampton. Of note, Lympne aerodrome, near Hythe, was designated as the third largest such airport in England, it operated from 1916 to 1984. By the beginning of 1933, Compagnie Aérienne Française service at Dover harbour was earning more from carrying post and light freight than passengers and it was possibly this that galvanised Southern Railway in to action. They employed consultants Airwork Services run by Air Vice Marshall Sir Henry ‘Nigel’ Norman (1897-1943) and Alan Muntz (1899-1985), with architect Graham Dawbarn (1893-1976) to look into possibilities of the Railway Company using seaplanes for freight transport.

While compiling their report, the consultants liaised through a junior officer, James Leslie Harrington (1906-1993 – and known by his middle name), within Southern Railway. Knowing Dover and remembering the seaplane base at Mote Bulwark, Harrington put forward the case for Dover harbour as an ideal place for Southern Railway to introduce a seaplane service. He pointed out that Dover’s then main railway station, Marine Station, was located on Admiralty Pier, to the west of the Prince of Wales Pier, from where Compagnie Aérienne Française operated.

Southern Railway published the report internally in March 1934. The consultants stated that besides Channel packet ships, ocean going and coal carrying ships were increasingly using the harbour. Although, Southern Railway could establish a successful air transport facility at Dover there were physical problems of using the harbour as a seaplane base. On the north-east side of the harbour, they wrote, were/are cliffs and along the Eastern Arm was the Tilmanstone Colliery aerial ropeway, both of which could be a liability. The harbour, itself, was notorious for its major negative tidal and wind effects and although the Channel Air Express, taken over by Air France in the summer of 1933, did offer a service, the previous summer it only operated 50 flights and hardly operated any during the winter. They also mentioned the landing field at Whitfield 3½ miles to the north of the harbour but this they also rejected.

However, the consultants enthusiastically suggested an alternative site. During the War, Nigel Norman had spent time as a Royal Flying Corps pilot at Swingate, which the consultants believed, would make a ‘splendid site’. At the time, the site was owned by the War Office and used by the Territorial Army except for a part that had been referred to as the Swingate aerodrome up to the War Office renting it out to a golf club a couple of years before. This, they suggested, almost certainly be made available for civil aviation. Further, the Swingate site offered the greatest possibilities for in 1933, Parliament approved a DHB Bill for a 1.75-mile railway line from the Kearsney junction, on the Deal line, through a tunnel to the Eastern dockyard. Southern Railway, Norman suggested, this could be used as a base for laying a line to Swingate and the ideal place for a Dover airport. The report was published and shelved. By that time Harrington had moved on becoming the Marine Manager at Dover and rising through the ranks of Southern Railways and its successors. He retired in 1969 as British Rail General Manager of the Shipping & International Services Division.

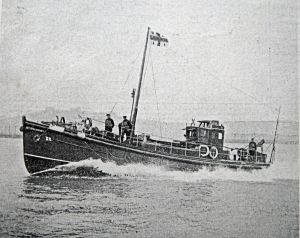

The RNLI Sir William Hillary Lifeboat, built 1930 and based at Dover primarily to rescue pilots and passengers on aircraft coming down in the Channel.

Back in the late 1920s, the recreational use of aircraft had started to increase and with this, the number of casualties. To deal with this growing problem, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) ordered a new and special lifeboat for their Dover station. Named Sir William Hillary after the founder of the RNLI, she came on station in 1929. Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) officially launched her on the Wellington Dock slipway on 10 July 1930 having flown in to what was then generally called Swingate aerodrome especially for the occasion. The Sir William Hillary’s successful rescues were predominantly maritime, due to the speed with which crashed aircraft sank.

Typically, in 1932 a German mail and freight aeroplane was reported missing, while on a flight from London to Berlin. The plane was a single-engine low winged Junkers that had left Croydon airfield, Surrey, at 20.55hrs with two crew and no passengers At 21.37hrs, three mayday distress signals in rapid succession were received but when the Dover lifeboat searched the area there was not a trace. On 2 October 1934, a twin-engine De Havilland 89 belonging to Hillman Airways and with a highly experienced pilot and six passengers on board crashed into the sea off Folkestone. On crossing the Channel, the pilot reported that the visibility was poor and Croydon suspected that he was off course. The Folkestone lifeboat recovered the bodies and the Dover lifeboat searched the area to collect evidence as to the cause of the accident. Of note, Hillman Airways formed November 1931 and from 1 December 1934 the airline was given the contract to fly airmail to Ostend and Brussels operated by the Railway Air Services. In 1935, the company merged with Spartan Air Lines Ltd and the British United Airways Ltd to form British Airways Ltd.

During 1934 the Royal Air Force was strengthened and several new types of aeroplanes were coming on station. These included Vickers-Scarpa twin engine flying boats and the four engine Short S.19 Singapore Mark III seaplane with living and sleeping quarters for the crew. In November units of the Coastal Area were engaged in operations against the Home Fleet, as it attempted to pass Dover harbour. Crowds turned out to watch and there was talk that Dover was to become a seaplane base again. By that time the riding school at Mote Bulwark had been refurbished as a second Territorial Army Drill Hall and the older Drill Hall became the Castle Garrison Library.

Correspondence was exchanged between Dover Harbour Board jointly with Southern Railway to the Royal Air Force and it slowly became evident that the re-establishment of a seaplane base at Dover was not even being considered. Albeit, Dover’s economy was picking up and the town was becoming increasingly popular with day-trippers. As the Mote Bulwark area was unlikely to be used as a seaplane base it was suggested that a lift from there to the Castle should be built. This was estimated to cost £9,788 and although Dover Corporation promoted the idea, World War II (1939-1945) was in the offing and the scheme was abandoned.

Meanwhile, changes had been taking place at Swingate. British scientist, Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, (1892-1973) had described a technique that he called Radio Detection and Ranging, or RADAR, to the British Air Ministry. He had been looking at ways to detect thunderstorms. With the help of his assistant, J F Herd, by 1923 he had constructed a low-sensitivity radio direction finder and by using three radiotelegraph receivers for triangulation, they could track the direction of an incoming storm. From this Watson-Watt and his team, drew up plans for a system to detect aircraft using radio waves and soon after five experimental radar stations were constructed, designated as Air Ministry Experimental Stations. One of these was at Swingate where four wooden transmitting towers were erected and to the east, four receiving towers at right angles to each other. The transmitting towers had large platforms at the top and halfway down and between the towers were strung long wave and short wave transmitting aerial arrays. Trials took place and by the late 1930s they had proved so successful that Chain Home System (CHS) consisting of eighteen radar stations were erected along the coast that gave early warning of approaching enemy aircraft.

World War II, the Nuclear Age and Neglect

Casemates above the Mote Bulwark that were the offices of the Commander-in-Chief of Fortress Dover, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945) . Alan Sencicle

In the final days before the outbreak of World War II, Dover was again taken over by the armed forces and designated Fortress Dover. As in World War I, restrictions were imposed and the Castle became the headquarters. From 24 August 1939, the Casemates above the Mote Bulwark took on an important role as the offices for the Commander-in-Chief of Fortress Dover, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945). These can be seen from the Seafront. The Vice-Admiral had served in the Dover Patrol between 1915-1918 and his first major duty was planning and co-ordinating Operation Dynamo, the Dunkirk Evacuation, (26 May to 4 June 1940). Some 100 Royal Navy Officers and 1,000 Women’s Royal Naval Service worked in the Casemates, helping to co-ordinate the rescue of 338,680 British and Allied servicemen from the French coast in the face of invading Germans.

Throughout this time, the Guilford shafts, first excavated in the early 19th century and developed during periods of hostility throughout that century (see Part I of the Mote Bulwark & Seaplane story), were lined with steel. Tunnelling and excavations created an underground hospital with the former underground Casemate barracks and tunnels being hollowed out to increase capacity. This created accommodation and a workplace for the Coastal Artillery, whose job it was to defend the Dover Strait. Below, and to a depth of some 144-feet (43.9-metres), excavations were undertaken to create DUMPY, started in August 1942 and completed by April 1943. The name DUMPY is often translated as Deep Underground Military Position Yellow and was to serve as The Channel Headquarters.

The Drill Halls and married quarters on the former Seaplane site, below Mote Bulwark, were used by the Royal Army Medical Corps to deal with medical emergencies from naval ships in the harbour. An anti-aircraft battery was built nearby. In early 1944, the World War I seaplane launchways and slipways were unearthed, repaired and used as landing stages to train troops in assault landings ready for the D-Day Landings on the beaches of Normandy from 6 June 1944. Once the Landings took place, the heavy bombardment that Dover had undergone since the beginning of the Battle of Britain on 10 July 1940, increased. As the Allied troops were drawing closer to Calais the attacks on Dover became even more intense. On Wednesday 28 June 1944, shells hit one of the former Drill Halls, killing three soldiers and injuring thirteen.

Opening of the Eastern Docks 30 June 1953. The photograph shows the Minster of Transport – Rt. Hon. Alan T Lennox-Boyd, Chairman of Dover Harbour Board – H T Hawksfield and the Register/General Manager of Dover Harbour Board – Cecil Byford. Lambert Weston.

Following the War the metal parts of the launchways and slipways were removed, leaving the concrete foundations. The Drill Halls were repaired and eventually were refurbished for use by the Territorial Army Voluntary Reserve and Divisional Headquarters. On 30 November 1946, Dover ceased to be a naval base and the Eastern Dockyard became a light and heavy industrial zone. One of the companies that opened was A.W. Burke, a small engineering firm that made specialist parts for the British aircraft industry, particularly jet engines. Then in 1953, the Eastern Docks opened as Dover’s second major passenger terminal and the industrial companies moved out.

Aimed at the private motorist, the Eastern Docks quickly proved to be very popular and the town roads serving it soon became congested. In 1956, the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation (1955-1959), Harold Watkinson (1910-1995) announced that a trunk road was to be created from Townwall Street to Eastern Docks and was completed in 1958. From Townwall Street, the trunk road took a right turn, opposite Mote Bulwark, into Duoro Place next to Gateway Flats. Then there was a sharp left turn on to the Seafront and then another sharp right turn on to Marine Parade towards the Eastern Docks. Traffic coming in the opposite direction used the same two lane narrow roads. Consequently, throughout the summer months it was congested, a situation that was to remain for over twenty years.

The armed services moved out of the Casemates in 1958 and the DUMPY level was taken over by the Home Office. The following year they were both refurbished as the top-secret Regional (South Eastern) Seat of Government in the event of nuclear war. The Complex provided radiation-proof living quarters for 420 people who may have had to remain underground for a considerable period of time. DUMPY was closed in the 1970s, in 1988 it was abandoned and finally declassified in 1992.

In the meantime, in February 1963, the Castle was handed over to the Ministry of Works, (Ancient Monument Branch), to be preserve as an ancient monument. The military retained St Mary-in-Castro as the garrison Church and the Constable’s Tower as the official residence of the local military commander, who was also the Deputy Constable of the Castle. After a time the Castle came under the auspices of Dover Corporation and from 1974, Dover District Council. The Grade I Listed Buildings, are now in the care of English Heritage and in 1990 the Dunkirk Operations rooms and the Casemate Level were open to the public and more recently, part of DUMPY.

Territorial Army site on the old Seaplane site, some years before demolition in the summer of 1981. Dover Express.

The Territorial Army moved to purpose built Head Quarters in 1980 built on the site of the old Odeon cinema, London Road, Buckland. Following this, the old Seaplane shed/Drill Hall was demolished in the summer of 1981. At the same time the cliffs above were ‘made safe’. The following year, the remaining Drill Hall and other buildings were demolished and a bypass of the Douro Place-Marine Parade, East Cliff, junctions was created. The situation improved but as the number of lorries using Eastern Docks increased so did congestion.

Following the Territorial Army moving to their new HQ at Buckland, their former HQ at Mote Bulwark was virtually rebuilt as an Army Recruitment Centre with an associated building to the east. Both closed in the late 1990s and in 2002 the 120-year lease of the then derelict buildings along with the site was put up for sale. They were sold through Avon Estates Ltd of London, to a private buyer but two years later the building and the site was on the market again. This time the asking price was £350,000, and there was a strong demand in the town for the site to be bought for an aeronautical museum. Dover Town Council were approached but said that they were not interested a number of private local consortiums were and offers were made, but turned down. The site was eventually sold in 2008 to a private buyer but it remained derelict, although in 2017, what had been a boathouse was taken over by second-hand goods store but burnt down on 10 July 2018. The site remains in a poor state.

Old Territorial Army buildings below Mote Bulwark on Townwall Street. Since demolished but the site remains overgrown and derelict. Lorraine Sencicle

Nonetheless, the demand for an aeronautical museum on the site remains. This would not only celebrate the Seaplane Base at Mote Bulwark and Dover’s other lost World War I airbases, such as Capel, Guston, Swingate, Whitfield and Hawkshill but also aeronautical pioneers with strong connections to Dover. Such as:

Jean-Pierre Blanchard (1753-1809) and Dr John Jeffries (1744-1819) – The first aviators to cross the English Channel by balloon.

Louis Blériot (1872-1936) – The first person to fly across the Channel in a heavier-than-air craft;

Charles Rolls (1877-1910) – the first two-way, non-stop English Channel flight;

and Harriet Quimby (1875-1912) – the first woman to fly across the Channel.

If only …

A Short version of this story was Published in the Dover Mercury on 26 October 2014 and a longer version was Uploaded on 8 July 2017. Following a talk given at Dover Museum on the World War I Seaplane base, as part of the Zeebrugge Raid Centenary celebrations, of 21 April 2018, the story was expanded to include a more detail account of Dover and Seaplanes. This was Uploaded to coincide with the Royal Air Force centenary.

For further information:

Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust: http://www.abct.org.uk