World War I (1914-1918), was the bloodiest war in modern history and after four years and three months Catholic politician and Chef de Mission – Matthias Erzberger (1875-1921), German Army General Detlof von Winterfeldt, Count Alfred von Oberndorff (1870-1963) of the German Foreign Ministry and Admiral Ernst Vanselow of the German Imperial Navy, signed the Armistice Document. This was witnessed by French Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) and Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss (1864-1933) the First Sea Lord, on behalf of the Allies. This memorable event took place between 05.12hours and 05.20hours, French time, on 11 November 1918 in Marshal Foch’s railway carriage in the Forest of Compiègne, Picardy, France. In attendance were French General Maxime Weygand (1867-1965), Rear-Admiral George Hope (1869-1959) – the Deputy First Sea Lord and Captain John Marriott (1879-1938) of the Royal Navy.

At 10.20hours, that morning the British Prime Minister (1916-1922), David Lloyd George (1863-1945) announced that, ‘the Armistice was signed at five o’clock this morning, and hostilities are to cease on all fronts at 11 a.m. to-day.’ At the precise time all fighting ceased on the battlefields and shortly after, it was estimated that during the conflict some ten million souls had perished. Of these, estimated at the time, about 960,000 were British and Dominion servicemen. By coincidence, the 11th of November is celebrated as St. Martin’s feast day, the patron saint of soldiers, France and Dover. Martin was a soldier in the 4th century Roman Army and on his discharge went to Poitiers, France. There, he became a disciple of Saint Hilary and in AD371, was appointed Bishop of Tours. Many miracles were attributed to him, most notably offering half of his cloak to a beggar at the gate of Amiens and afterwards experiencing a vision of Christ relating the charitable act to the angels. It is for this act that St Martin was venerated and this is how he is depicted in Dover’s coat of arms.

World War I Victory Parade 19 July 1919 the Cenotaph was a temporary structure for the occasion. Evelyn Larder Collection

A year after the signing of the Armistice, in 1919, at the then recently erected wood-and-plaster temporary Cenotaph – designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944), in Whitehall, London a special Armistice Day service was held. The monument had been erected for the Victory Parade held on 19 July 1919 and was scheduled for demolition shortly after. However, pressure from the general public was such that by the end of the month it was announced that the temporary Cenotaph would remain until replaced by a permanent structure and would be in memory of all who had fallen during World War I. The Portland stone Cenotaph, which is seen today was started in early 1920 by Holland, Hannen & Cubitts of London and was scheduled to be unveiled by King George V (1910-1936). As part of the 1919 Armistice Day service, for two minutes from 11.00hours all but essential traffic, including railway trains, were stopped and silence was observed. Up until 1945, Armistice Day continued to be celebrated on 11 November and included the two-minute silence.

During World War I, some 300,000 British and Dominion soldiers with no known grave had been killed and there was a groundswell of public opinion that a representative nameless hero of the War should be dignified with a national burial. The government, in 1920, appointed George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (1859-1925) to look into the possibility. Lord Curzon was a senior Conservative politician who in 1905, had held the position of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. He set up a committee and it was agreed that Westminster Abbey would be a fitting burial place. Although it is said elsewhere that George V was against the proposal, the King immediately announced that he would represent the nation as the chief mourner at the burial. The date chosen was 11 November 1920 – Armistice Day and the day chosen for officially unveiling the newly built Cenotaph.

Following George V’s announcement, applications to attend the Westminster Abbey service came from some 1,500 of British and foreign members of high society and dignitaries, but Lord Curzon had other plans. The service in Westminster Abbey would take place after the Cenotaph service where representatives of the fighting forces would be. At the Abbey, there were places for 2,800 people and seating would be available at the windows in the Government Offices along Whitehall.

There would have to be seats at the Abbey for the immediate Royal family, 40 representatives of the Government and Dominions – including two Prime Ministers that had served during the War – the heads of the prominent religious denominations and principal walks of public life. A further two hundred were to be set aside for Peers and Members of Parliament who had lost a close relative in the War and a hundred for representatives of the various ex-servicemen organisations.

Thus, there would be approximately 2,400 seats at the Abbey and these, the Curzon committee decided, would be made available to the relatives of those who had fallen but whose identities had been lost. At the top of the list were women who had lost their husband and sons or husband and only son. Next, were mothers who had lost all or only sons. Third, widows who had lost their husband and finally, women who had lost their husband or sons but whose graves was known. If there were more applicants than seats the same principle was to be applied to the allocation of seats in the government office windows along Whitehall. For those who were still unlucky there would be a reserved section along Whitehall, near the Cenotaph. If, on the other hand, the spaces were not all taken, there would be a ballot of those who had lost a close relative with a known grave.

The War wounded had areas reserved for them along Whitehall near the Cenotaph as long as they wore their medals and ex-servicemen, also wearing their medals, would have sections reserved from them. They would all be encouraged to join in a parade following the Cenotaph Service and to lay wreaths, if they wished, during a slow march past. They would also have sections reserved for them outside of the Abbey.

The Curzon report was accepted by Parliament and the order of the proceedings was such that the King, Royal Princes, the government, church and the other representatives would all be attending the Cenotaph service before going to Abbey. The unveiling of the new Cenotaph was to take place at 11.00hours and for two minutes, excepting essential traffic, all traffic including railway services was to be stopped. However, Parliament decided, the occasion would not be a Bank Holiday as, they decreed, it would cause a great dislocation of business and a public holiday was one for ‘national rejoicing and therefore hardly suitable for a day on which so solemn and an impressive ceremony was to take place.’

Members of Parliament representing naval constituencies asked if an unknown sailor could be buried alongside the soldier to which Prime Minister, Lloyd George responded by saying that ‘representatives from the Admiralty and from the Air Board had attended the discussions. The conclusion come to be all the Services was that under the circumstances the course that has been adopted is the right one. The inscription on the coffin is not a soldier but as an unknown warrior.’ (Hansard 01.11.1920) Representatives from foreign governments asked if they could have seats at Westminster Abbey but were told that they could attend the Cenotaph service, the service at the Abbey was exclusively a national ceremony.

Meanwhile, officers and soldiers had been sent to Aisne, Arras, Pyres and Somme – the four major battlefields – to exhume four bodies of soldiers buried there who had died in the early years of the War. The bodies had to be as old as possible in order to ensure they were sufficiently decomposed to be unidentifiable. Having been examined to check that there were no identification marks, the four bodies were wrapped in old sacks and taken to a chapel at Saint Pol-sur-Ternoise, near Arras, northern France. This was on 7 November 1920 and there the Reverend George Kendall (1882-1961) and two undertakers received the bodies. At the stroke of midnight Brigadier Louis John Wyatt (1874-1955) General Officer Commanding British Troops in France and Flanders and Lieutenant Colonel EAS Gell of the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries went into the chapel alone.

The bodies were on stretchers, each covered with a Union Jack. The two officers did not know from which battlefield the individual bodies had come from. Brigadier Wyatt, in some reports say blindfolded, others with his eyes closed, touched one and then the two officers placed that body into a rough coffin, which had been left for the purpose. The other three bodies were given a ceremonial burial led by Reverend Kendall. The one chosen was taken by an army ambulance to Boulogne and carried into the Officers’ Mess by eight non-Commissioned officers drawn from the various Armed services including one from Australia, another a Canadian. There, it was then taken into the library that had been quickly converted into a Chapelle Ardante. The floor was strewn with autumn flowers and the coffin was placed on a table, covered with a tattered Union Jack from the Front and guarded by the non commissioned officers.

HMS Verdun – Admiralty ‘V’ class torpedo-boat destroyer that carried the Unknown Warrior home to Britain. Wikapaedia

In the meantime the British torpedo-boat destroyer, HMS Verdun, carrying an iron bound oak coffin provided by the Undertakers Association had arrived at Boulogne. The Union Jack covering the coffin was the same one used to cover the coffins of Nurse Edith Cavell (1865-1915) and Captain Charles Fryatt (1872-1916) when their bodies were brought home. Nurse Cavell had helped some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium to neutral Netherlands during the War. She was arrested and tried on 7 October 1915 and shot five days later. Captain Charles Fryatt had commanded the Great Eastern Steamer Brussels, which had been a scourge to German shipping. Captured in June 1916 after he had failed to ram the German U-33, Captain Fryatt was convicted before his trial and executed on 27 July 1916. The Verdun was named after French victories at Verdun, and was one of twenty vessels of the Admiralty ‘V’ class then in service. Built by Messrs Hawthorn, Leslie and Co. at Hebburn-on-Tyne she was delivered in November 1917 and attached to the Fourth Destroyer Flotilla of the Atlantic Fleet. Her commanding officer was Lieutenant-Commander Colin S Thomson.

The iron bound oak coffin was taken to the Chapelle Ardante and the body was moved from the rough coffin and placed into the oak one. Fastened to the lid was a sword from George V’s personal collection and a plaque bearing the inscription:

A British Warrior who fell

in the Great War 1914/1918

In the early hours of the 10 November, the eight non-commissioned officers, who had vigil, placed the coffin, covered with the Union Jack that Captain Thomson had brought from England and wreaths, onto a wagon. With an escort of French and British soldiers the precious cargo was taken through Boulogne where, even though it was early in the morning, thousands of French men and women lined the streets to pay their respects. One Frenchman summed up the general feeling by saying that the British Warrior had died ‘for our country as much as his own.’ At the Quai Gambetta, where the Verdun was tied up was Marshall Foch and General Weygand. The White Ensign was lowered to half-mast while the coffin was carried up the gangplank and piped aboard with an Admiral’s salute.

The Verdun, with an escort of destroyers, arrived outside Dover’s Western entrance at 13.00hours. The sky, it was reported, was solid grey – appropriate to the occasion. The colour was reflected in the calm sea and the normally white cliffs of Dover took on a grey hue as did the town and Castle. Although Dover’s seafront was crowded, all was quiet when at 15.00hours the Verdun, followed by her escort, slowly steamed along the entire length of the Southern breakwater to the Eastern entrance. From there she came in alone, the escort of destroyers having returned to sea. The Verdun made her way across the harbour and at the same time the Field-Marshal’s salute of 19 guns was made from the Castle. The silence returned and the lines of troops waiting along the entire length of the Admiralty Pier stood, their heads bowed and arms reversed.

As the Verdun drew closer to her mooring, stern first, the military bands on the quayside struck up Sir Edward Elgar’s (1857-1934), Land of Hope and Glory. In the stern was the coffin covered by the special Union Jack on top of which were wreaths given by the French, the crew of the Verdun and the various British Units that had attended during the Unknown Warrior’s time in Boulogne. At each corner was a Verdun sailor, with his head bowed and rifle reversed. Behind stood the Adjutant-General, Sir George McDonough (1865-1942). The Verdun crew were at their stations standing to attention. The coffin was taken off the ship by six warrant officers, representing the different services all of which had taken an active part in the War. It was then passed to the pallbearers – six senior officers of the different Services who too had played an active part. The Adjutant-General followed the coffin and after him came Major General Sir John Raynsford Longley (1867-1953) and Colonel Knight who was in command of the Dover garrison.

The coffin of the Unknown Warrior being carried along Admiralty Pier to the awaiting train. Dover Mercury

On the quayside were dignitaries representing Royalty, the Armed Services and the Church as well as Dover’s Mayor Charles Selens and Councillors. The coffin was then transferred, with great ceremony, into the waiting South Eastern and Chatham Railway passenger luggage van no 132. The same special carriage that had carried the bodies of Nurse Cavell and Captain Fryatt. Inside was decorated with laurels, palms and lilies and the coffin, still covered with the Union Jack, was guarded by four servicemen, arms reversed and representing each of the armed services. The wreaths, carried from the Verdun, were placed on the top of the coffin.

However, locals were prevented from paying their respects at Admiralty Pier, which caused a great deal of upset. The Dover Express commented, ‘Not even those widows from Dover who mourn their husbands who have no known grave, were allowed entry.’ At the time the villages of Eythorne, Swingfield, St Margaret’s and Temple Ewell had unveiled War Memorials to their inhabitants that had been killed. In Dover, there was a strong movement wanting the town to forget about the past and to concentrate on moving forward. It was not until the 29 October 1924 that Dover’s War Memorial, in front of the Maison Dieu House, was unveiled. Sculpted by a former student of Dover’s Art school, Richard Reginald Goulden (1876–1932), it was unveiled by Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes (1872-1945), who oversaw the Zeebrugge and Ostend Raids. Most of the town‘s inhabitants including War-time Mayor, Sir Edwin Farley, attended. A plaque was added after World War II in memory of locals who fell during that conflict.

A small shunting engine that also hauled two more carriages pulled the long railway carriage carrying the Unknown Warrior from Dover to London. One carriage was full of wreaths and flowers and the other, soldiers. As the train steamed into Victoria station it had an impromptu effect on those on the concourse. Dignitaries and onlookers alike fell silent and quietly wept. The silence remained as the train drew to a halt and Officers and Grenadier Guardsmen drew up, saluted, but the silence continued. The coffin was taken to a specially created Chapel of Rest at the station and everyone stopped and bowed their heads.

The weather on the morning of 11 November 1920 was bright and clear. The coffin was placed onto a gun carriage and covered with the special Union Jack. On the flag, soldiers placed side arms and a steel helmet. Taking their positions at the side were, Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdoe (1859-1945), Admiral Sir Charles Madden (1862-1935), Field Marshal John French 1st Earl of Ypres (1852-1925), Field Marshal Lord Haig (1861-1928), Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson (1864-1922), General Lord Horne (1861-1929), General Julian Byng Viscount Vimy (1862-1935), and Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard (1873-1936). The Unknown Soldier left the railway station followed by lines of soldiers doing a slow march to the sound of muffled drums. The entourage took an hour to reach the Cenotaph and along the way the London streets were crowded with silent, motionless, folk – many with their heads bowed.

George V and the selected dignitaries were at the Cenotaph and when the coffin arrived the first thing the King did was to place a wreath of laurel leaves and crimson flowers on the top of the coffin. A brief service followed and when Big Ben struck 11.00hours, George V pressed a button and the Cenotaph veiling flags – Union Jacks – dropped to the ground and two minute silence ensued. The stillness was broken by the sound of the Last Post and George V placed a wreath at the base of the Cenotaph. This was followed by the lying of wreaths by dignitaries and appointed representatives of the armed services.

Headed by massed bands, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London and the heads of the other denominations, they left the Cenotaph. Behind them the coffin of the Unknown Warrior was escorted by the senior military personnel, followed by the King, the Royal Princes and the dignitaries. Four sentries were posted at the Cenotaph, one at each corner drawn from the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Army and Royal Air Force, heads bowed and resting on their Arms reversed. Then came the march past by members of the Armed Forces of Britain and the Dominions, followed by hundreds of former service personnel all wearing their medals and many carrying wreaths.

Family members of those lost during the War were already in the Abbey when non-commissioned officers of the Guards carried the coffin in. They passed between two lines of men who had either won the Victoria Cross or had otherwise been distinguished for special valour during the War. George V walked behind followed by the Princes, Peers, Statesmen and selected dignitaries. The coffin was lowered into the grave and the King scattered it with soil brought from the battlefields. Hymns were sung and the short service ended with the throbbing of drums and bugles sounding the réveille.

Following on from the former servicemen and women passing the Cenotaph came the ordinary folk of which there were so many that there were still queues as darkness fell. After the service had finished in Westminster Abbey, members of the Armed forces, former service personnel and ordinary folk filed passed the tomb of the Unknown Warrior until closing time. The next day and for days after both the Cenotaph and the tomb of the Unknown Soldier were visited by thousands. On one afternoon a number of ex-servicemen, in wheelchairs having lost both legs, lay wreaths at the Cenotaph before going on to the Abbey. On one of the wreaths were inscribed the words ‘Lest We Forget.’

The tomb of the Unknown Warrior was finally sealed on 18 November 1920 by which time over one million people had paid their respects. Soil brought from the battlefields of France and Flanders filled the grave. Capped with a black Belgian marble stone, the inscription by the Dean of Westminster, Herbert Ryle (1856-1935) engraved in a brass plate from melted down wartime ammunition reads:

Beneath this stone rests the body // Of a British warrior //Unknown by name or rank // Brought from France to lie among // The most illustrious of the land // And buried here on Armistice Day //11 November 1920, in the presence of // His Majesty King George V // His Ministers of State // The Chiefs of his forces // And a vast concourse of the nation //Thus are commemorated the many // Multitudes who during the Great // War of 1914 – 1918 gave the most that // Man can give life itself // For God // For King and Country // For loved ones Home and Empire // For the sacred cause of justice and //The Freedom of the World // They buried him among the Kings because he // Had done good toward God and toward // His House

Around the main inscription are four texts, at the top: The Lord knoweth them that are his, the side: Unknown and yet well known, dying and behold we live, the other side: Greater love hath no man than this and at the base: In Christ shall all be made alive.

One of those who stood in silence that day at the Cenotaph and walked down to gaze into the tomb of the Unknown Warrior was a young soldier, brought up in Dover and suffering from shell shock. His name was Edward Aldington (1892-1962) and using the name Richard Aldington, not only became one of the county’s acclaimed War Poets he is acknowledged as such in the Poets’ Corner, in Westminster Abbey. Christened Edward Godfree Aldington, he was born at Portsmouth on 8 July 1892, the eldest son of Albert Edward Aldington (1864–1921), bookseller and later a solicitor‘s clerk and his wife, Jessie May Godfree (1872–1954). Jesse later became an acclaimed novelist in her own right and was the keeper of the Mermaid Inn, Rye.

The family came to Dover around 1898 and after attending preparatory schools at Walmer and St Margaret’s, Edward was enrolled into Dover College in 1904, which apparently he did not like. His father Albert opened his own legal practice at 18 Castle Street about 1905, and it was expected that Edward would train to become a solicitor when he grew up. However, Albert’s business acumen left a lot to be desired and after two years, the family, which by this time included two daughters, moved to Eastry and Edward left Dover College. The family then moved to Kingston-upon-Thames where, in 1911, another son, Paul – known as Tony – was born. When Edward was about 17-years-old he published his first book of poetry and shortly after enrolled at University College, London.

Due to his father’s continuing financial problems, Edward had to leave university before graduating but he did manage to secure a job as a sports writer. Albeit, Edward’s real interest was writing poetry and prose and he soon came under the wing of literary hostess, Ethel Elizabeth (Brigit) Patmore (1882–1965). Bridget introduced Edward to like minded individuals, including poet and critic Thomas Ernest Hulme (1883-1917) who had founded the influential Imagist Movement in the United States. With poet and critic Ezra Pound (1885-1972), poet and translator Frank Stuart Flint (1885-1960) and American poet and novelist Hilda Dolittle (1886-1961) – known as H.D – Edward was a founding member of the British Imagist Movement. Others who joined included Folkestone’s novelist and historian John Mills Whitham (1883-1956) and Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888-1965) known as T.S.Eliot. The Imagist principles were that of directness, precision, concreteness and free rhythmic cadence and Edward was the editor of their magazine, The Egoist. In 1913 Edward and H D married and in 1915 they published their joint work on translations from Greek and Latin, Images, Old and New.

Richard Aldington- Images of War 1919 front cover, designed by Paul Nash and published by Cyril William Beaumont of Beaumont Press

At the outbreak of World War I, having been rejected as unfit for military service, Edward worked as the secretary to novelist and poet Ford Maddox Ford (1873-1939) writing propaganda material. Albeit, Edward continued to apply to join-up and on 24 June 1916 he was accepted by the 11th battalion of the Devonshire regiment. T.S.Eliot, took over the editorship of The Egoist and Edward was reported as saying that ‘I was 19 when I was brought into it, and by 1916 I was deep into first war and out of Imagism.’ (Victory in Limbo – A History of Imagism 1908-1917 by J B Harmer – Secker & Warburg 1975). Securing a Commission six months later Edward embarked for the Front. During the remaining war years, he saw some of the worst fighting in France and Flanders. One of his jobs was to collect the identification discs of those who had been killed. Of this, he later wrote:

‘Well, as to that, the nastiest job I’ve had

Was last year on this very front

Taking the discs at night from men

Who’d hung for six months on the wire

Just over there.

The worst of all was

They fell to pieces at the touch

Thank God we couldn’t see their faces;

They had gas helmets on …’ (Images of War, Beaumont Press, 1919)

Besides shell shock Edward suffered from chronic bronchitis due to exposure to mustard gas and he was gazetted out of the Army in February 1919. Shortly after he and H D separated. During the War, American art student Dorothy (Arabella) Yorke (1891–1971) had moved into the flat above the Aldington‘s. She and Edward became lovers and they stayed together for a number of years. Using the first name of Richard, Edward wrote his anthology of War poems, the Images of War. The cover and the decorations were designed by surrealistic artist Paul Nash (1889-1946) and the typography and binding was arranged by Cyril William Beaumont (1891-1976). The book was printed by hand on Beaumont’s press at 75, Charing Cross Road, Westminster, London on the evening of St George’s Day (23 April) 1919.

Although, initially, only a limited number of the anthology were published it was a great success and Edward adopted the name Richard. He and Arabella moved to Berkshire where Richard worked as a critic and translator of French poetry. He also wrote a book about his friend, novelist David Herbert (DH) Lawrence (1885-1930): D. H. Lawrence, An Indiscretion. Signed up by Alexander Stuart Frere (1892-1984) for the publisher William Heinemann – Frere later became the chairman of the publishing House – he encouraged Richard to write. Over the next ten years Richard produced a proliferation of novels, short stories and poems. His most famous novel, Death of a Hero, was published in 1929 and was described by novelist and critic George Orwell (1903-1950), as ‘the best of the English war books.’ It is a semi-autobiography centring on a George Winterbourne who enlists in the army at the outbreak of World War I. As a poet, Richard’s acclaimed piece was A Dream in the Luxembourg, dedicated to his old friend, Brigit Patmore. In recent times it is seen as evocative of the 1920s.

The first time the BBC broadcast the Armistice Day ceremony was in 1930. That evening the Company broadcast the British Legion’s Festival of Remembrance from the Albert Hall and was followed by an anthology of War poems, including Richard’s. In the early 1930s, journalist Mark Goulden (1898-1980) took over the editorship of the Sunday Referee turning it into a lively and popular journal for the British thinking classes. His columnists included many famous intellectuals from the literary world and Richard was one of those who contributed. However, Richard spent much of the late 1920s to the mid-1930s in France with DH Lawrence and Brigit Patmore. While in France, he wrote seven novels and discovered and encouraged Irish novelist Samuel Becket (1906-1989).

In March 1936, Richard led a contingent of well known authors, including T.S.Eliot, Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), A.A. Milne (1882-1956), Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962), H G Wells (1866-1946) and Virginia Woolfe (1882-1941), in a plea to the British government to change the laws of libel. At the time an author only had to describe a fictional character, for a person with means to seek legal action. They would then contend that the character was a deliberate misrepresentation of them and provide two witnesses to confirm the accusation. However, in November 1937, Richard was in court and was forced to pay £1,500 in damages. He had been cited in a notorious divorce case for having committed adultery with Netta McCulloch (1911-1977), the daughter-in-law of Bridget Patmore. Later that year Richard and HD finally divorced and he married Netta. During World War II (1939-1945) the couple moved to the United States.

During his time in the US, Richard worked in Hollywood and New York, but his greatest achievement was his biography of the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), published in the US in 1943. In March 1947, following the book’s publication in the UK, Richard was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for best biography. By this time, Richard was an acknowledged author of biographies but his work on T.E. Lawrence (1888-1935), Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry, came in for a great deal of flack by British critics. Richard had spent a great deal of time in France during the Inter-War years, where Lawrence was seen as an enemy and the critics there applauded Richard’s biography. In essence, Richard had painted Lawrence as a legend of his own making. Following the publication, Richard was effectively blacklisted in the English speaking world, but by the late 1950’s, his works were back on the shelves. Following which, they were translated into Russian where they became very popular.

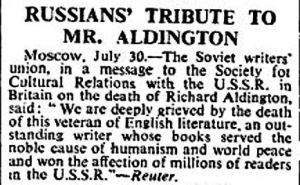

Richard Aldington died at his home at Sury-en-Vaux, France, on 27 July 1962, having recently returned from Russia. On hearing of his death the Russian Society for Cultural Relations wrote, ‘We are deeply grieved by the death of this veteran of English literature, an outstanding writer whose books served the noble cause of humanism and world peace and won the affections of millions of readers in the USSR.’ Some in the British press took a different stance with the Times of 30 July saying that Richard was an ‘Angry Young Man, years before they became fashionable and became an Angry Old Man.’ However, the Telegraph, of the same day, was kinder saying that, ‘Aldington’s brilliance in so many fields of literature has been rivalled by few of his generation and is indeed rare at any time’. To date there is nothing in Dover to mark this celebrated writer.

Richard’s brother, Paul Anthony Glynn Aldington – Tony, became a solicitor and marrying in 1932, he returned to Dover living and practising at 25 Castle Street. Tony remarried in 1948 and in 1953 was joined in the practice by Welshman, Thomas Robert (Bob) Davies. On 1 October 1963, the partnership was dissolved but both men appeared to carry on working in the practice. Tony became a salaried partner on 1 April 1964 and retired in July that year. However, on 25 May 1965, Tony was struck off the roll of solicitors, having been found guilty of breaches of the solicitors’ accounting rules. His name was restored in July 1974 but in the meantime the firm of solicitors, Knocker, Elwin and Lambert absorbed his and Davies’ practice. Later, Knocker, Elwin and Lambert was of one of the firms that amalgamated to become Knocker, Bradley and Pain – the present day Bradleys solicitors now in Maison Dieu Road.

Unknown Warrior – Unveiling of the Dover Society Plaque programme at Marine Station 17.05.1997. David Iron Collection

Up to World War II (1939-1945), the annual National Service of Remembrance was held on the closest Sunday to Armistice Day, 11 November. Following the War, Remembrance Sunday was fixed as the second Sunday in November. The Unknown Warrior’s grave in Westminster Abbey is the only floor grave/stone in the Abbey that people are not allowed to walk on. On 11 November 1985, 16 Great War poets were commemorated by a slate stone unveiled in the Abbey’s Poets Corner and Richard Aldington heads the list. The inscription, from the work of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) reads: ‘My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.’

On 17 May 1997, at the former Marine Station on the Admiralty Pier, Dover – now the entrance to Cruise Terminal One – General Sir Charles Guthrie, Chief of the Defence Staff unveiled a plaque commemorating the arrival of the body of the Unknown Soldier into Britain. Commissioned by the Dover Society, Sir Charles said that, ‘the plaque would remind people that the Unknown Soldier was one of 908,000 soldiers, sailors and airmen from the British Empire who went out and were killed in World War I.’

Presented: 11 November 2015

Shortened Version in the Dover Mercury: 03 & 10 November 2011