The 1606 Dover Harbour Charter did not include land to the east of the Boundary Groyne on Dover’s seafront. At that time, much of this area was covered by sea at high tide. However, harbour works, at the western end of Dover’s great bay was causing the Eastward Drift to deposit shingle below the Castle cliff. This, from mid 18th century was being built on. The inhabitants claimed the area as theirs until asked to contribute to the repairs of Castle Jetty. Their objection led to Dover Corporation taking over the beach and the inhabitants were obliged to pay rates to Dover Rural District Council until 1934.

For a long time there had been the demand for a Harbour of Refuge along the Channel coast and in the early 19th century the demand centred on Dover as the ideal port to serve this purpose. The first stage of the Harbour of Refuge was the Admiralty Pier, started in April 1848 and completed in 1871.

In 1893, Dover Harbour Board (DHB) decided to create a Commercial Harbour using the Admiralty Pier at the west and building a second – the Prince of Wales Pier – as the eastern boundary. It was envisaged that this would, with the then end of Admiralty Pier, create an entrance into the Commercial harbour. The Prince of Wales Pier was opened on 31 May 1902 by the Marquess of Salisbury, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. However, before then international changes brought a change to its finished design.

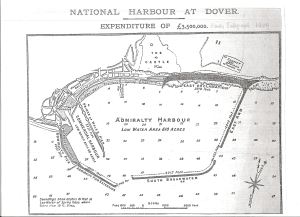

The German government, under Bismark, had been building up armaments and warships and in 1897 the Admiralty announced that it was to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy. They envisaged the closure of the whole of Dover bay with a harbour comprising of a 3,320ft (1,012 metres) Eastern Arm and a 4,200ft (1,280 metres) long Southern breakwater curving from the Eastern Arm to the Admiralty Pier. To meet the Breakwater and so creating the western entrance, the Admiralty Pier was to be extended by 2,000ft (610 metres). This change of plan meant that the end of Prince of Wales Pier was turned less to the south-west than was originally intended. Work began in December 1898 with the extension of Admiralty Pier.

S Pearson & Sons’ tendered to build the Admiralty Harbour. This was accepted on 5 April 1898 in co-operation with Sir John Jackson, engineer, who had been responsible for the Prince of Wales Pier. The ironwork for the new harbour was sub-let to Messrs Head, Wrightson & Co of Teesdale Iron Works, Stockton-On-Tees. Different aspects of the construction were sub-let including to local firms including Barwicks.

The actual building of the Eastern Arm, 2,800-feet (approx. 854 metres) in length and with depths between 26-32 feet (7.93-9.8 metres), was started in January 1901. Initially the seabed was levelled from diving bells, each measuring 17-feet (5.2-metres) long by 10-feet (3 metres) wide and weighed 35 tons and said to be the largest in the world. They were lit by electricity and the air was pressurised at 27lbs per square inch. Four men at a time worked inside them for three hours.

The spoil was raised by giant grabs lowered by crane and carried away in trucks hauled by steam locomotives. As work progressed, a temporary bridge was built and a track was laid on the Southern Breakwater. The frame for the Arm was built out of Huon Pine, a heavy wood that does not float and was brought from Dover, Tasmania. Using this framework, massive concrete blocks were laid.

These were made in a dockyard covering 24½ acres (9.915 hectares) built under the East Cliff. It had been formed by the reclamation wall, 4,000 feet (1,220 metres) long, back-filled with chalk from the cliffs. Shingle and sand came from Stonar, near Sandwich, and was brought by railway to Martin Mill and then on the specially constructed Dover Martin Mill Railway. The shingle and sand were mixed with concrete and water in six lines of giant electric mixers. The contents were emptied into giant moulds and some 250 blocks were made at the same time.

Two goliath cranes, with a span of 100-feet (30.5-metres) and a lifting capacity of 50-tons were used to move them. The blocks were dovetailed and keyed together with concrete and laid, on average, 600 a month. They were faced with granite that was shipped in from Plymouth. Men, wearing diving suits and breathing compressed air that was pumped down to them, put the blocks into their final positions.

The Eastern Arm was completed by 1904 and in May 1905, an official notice was published stating that the Admiralty had taken over the sole control of the Eastern Dockyard – the name then given to the reclaimed eastern part of the bay.

In January 1908, Messrs Pearson secured the contract for the erection of a Camber or tidal dock at the Dockyard for a submarine station. Work started immediately on the 1,000 feet square (304.8 metres square) Camber. The minimum depth was 15-feet (4.58 metres) at low tide and it was protected from all seas.

At the end of January 1909, the 650-feet wide (198-metres) eastern entrance was opened and a fort was erected at the seaward end of the Arm. This had breech-loading medium and light quick-firing guns mounted in concrete emplacements along with searchlights, quarters, and magazines. There was also machinery for a quick drawing boom to be put in place across the harbour entrance if needs necessitated.

Official opening of the Admiralty Harbour, Eastern Arm. Stone laid by the Prince of Wales 15.10.1909

The Admiralty harbour was officially opened on 15 October 1909 by HRH the Prince of Wales. The final Stone, which he ceremonially laid, is on the inside of the Eastern Arm wall at the cliff end. In 1910, oil installations in the shape of two oil tanks with a holding capacity of 110 tons and costing £10,000 were erected for the proposed submarines.

In July 1911, Germany sent her gunboat Panther to Agadir, Morocco to supposedly protect the country’s firms even though the port was closed to non-Moroccan businesses. The Admiralty reacted by, amongst other things, ordering the Camber to be altered for use by both torpedo craft and submarines. The depth was deepened to 17-feet (5.19 metres); a pair of breakwaters and submarine shelters was constructed with a small dry dock along side. In addition, several lubricating oil tanks were erected and a new asphalt road was laid.

As international tensions deepened so was the Camber in order to create a safe anchorage for destroyers. In 1913, tests proved satisfactory and it was finished by March 1914 becoming operational on 22 May that year. A parapet on the Southern Breakwater was erected at a cost of £27,000 and oil-fuel storage facilities were increased at a cost of £5,800.

Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914 and a floating dock was brought to the port and placed in the Camber. The boom across the entrance was put in place but it fitted so badly that it was carried away during a heavy sea, as was its replacements!

Although the Dockyard was designated for the repair of auxiliary craft, destroyers and submarines by naval staff, the work was actually carried out by Dover Engineering Company. The caves behind the Dockyard were used for the safe storage of explosives and ammunition while the Camber became the base for fast motor torpedo boats, gunboats as launches, pinnaces, and tugs. Even though facilities for the seamen, such as barracks had not been given consideration. In order to carry explosives to ships berthed in the Camber, the Sea Front railway from the Harbour station at the Western docks opened in 1918.

Towards the end of the war, the Naval uses of the Eastern Dockyard diminished so the facilities were used for ship repairs. Following Armistice, the Dockyard was used for shipbreaking of ships classed as obsolete and in March 1920, the Admiralty leased the Dockyard to Stanlee Shipbreaking Company for ten years. The firm’s first job was the battleship Duncan that arrived in Dover on 18 June 1920. Shipbreaking soon became a major activity that employed up to 600 men except during a temporary slump in steel prices in 1921.

Back in 1889 the Post Office Marine Division had acquired the privately owned Submarine Telegraph Company. This firm had been responsible for laying the first submarine telegraph link between England and the Continent. At the time of the take-over, the company’s vessel was the paddle steamer Lady Carmichael, which the GPO renamed H. M. T. S. Alert. A second ship of the same name built by Swan, Hunter and Wigman Richardson in 1918 replaced her. The Division was based at Western Docks until 1921, when it moved to purpose built accommodation in the Camber. The lifeboat station, which had closed for the duration of the war, opened again in 1919, using the Camber, but closed in 1922.

On 29 September 1923, the Admiralty Harbour, comprising of 610 acres, was handed over to the control of the DHB and officially renamed the Outer Harbour. The Admiralty retained the Camber. Stanlee Shipbreaking Company, although still working at full capacity, were aware that the numbers of ships to be broken up was ending. Negotiations started with colliery owners, Pearson Dorman Long to take over part of the lease for a coal yard.

The Official Receiver wound up the Stanlee Shipbreaking Company in 1926 and the remaining time of the lease was taken over by A G Hill Ltd. They undertook an extensive trade in scrap metal particularly exporting to Spain. The Admiralty relinquished their control of the Camber the spring of 1927 to DHB, having removed the floating dock and crane to Rosyth in 1925. The Post Office submarine cable depot remained.

On 5 November 1926, application was made by Tilmanstone (Kent) Collieries Ltd for the right to carry an Aerial Ropeway for a distance of 6½ miles from the colliery to the Eastern Arm. The proposed course extended over land owned by 18 different personages one of whom was Southern Railway. Although permission was granted, Southern Railway, amongst others, appealed.

At a hearing, held on 17 March 1927, the application was refused. At the same time, Southern Railway sought permission to carry coal on the Seafront Railway and along Eastern Arm to specially built giant bunkers. The main shareholder of Tilmanstone Colliery was Richard Tilden Smith, who, after fierce battle, won the right to erect the aerial ropeway. Permission was also given for two tunnels to be cut through the cliffs. However, before the now 7½ mile aerial ropeway was completed Tilden Smith died on 18 December 1929, in the House of Commons. The formal opening of the ropeway took place on 14 February 1930 when the coal from Tilmanstone carried in buckets. Each bucket weighed 5hundredweight and had the capacity if 16hundredweight. Tilmanstone coal were emptied into a massive coal staithe capable of holding 5,000 tons of coal and built by the Yorkshire Hennebique Company . The first ship to be loaded was the collier Corminster belonging to Messrs W Cory and Co.

The Lifeboat was brought back into service from the Camber in 1929 and in May and the following year the Post Office replaced the wooden jetty with reinforced concrete. The Yorkshire Hennebique Company carried out the work. In the meant time in July 1928, Captain Stuart Townsend chartered the 386-ton coastal collier Artificer and launched a new car-carrying cross-Channel service between Dover and Calais for the transport of motorcars. Although vehicles had to be craned on and off, some 6,000 vehicles were carried that year and various motor associations opened special shipping offices in the town. The Artificer was replaced by the Royal Firth followed by the Forde, an adapted Admiralty sloop costing £5,000 that carried 168 passengers and 26 cars. The Forde, made her first trip on 15 April 1930 and although her stern door could be folded down onto the quay enabling cars to be driven on or off, because of the variable heights of tides, cars had to be craned.

In August 1928, work started on Tilden Smith’s giant coal staithe however when it was almost ready, Southern Railway and Pearson Dorman Long who owned Snowdown and Betteshanger collieries, through DHB, asked for the staithe to be altered. They wanted a lower staithe constructed and to use the giant staithe’s loading facilities but Tilden Smith refused. Coal, up to that time, had been unloaded at Western docks but due to passenger trains using Marine Station and goods trains using the Wellington and Granville Docks, congestion was a major problem. In 1923, an Act of Parliament had allowed the military built Seafront Railway, by then in the ownership of DHB, to be used once a day. It seemed natural to use this Railway to carry coal from Western Docks to the Eastern Arm and together with the coal brought in by the aerial ropeway justified the giant coal staithe.

Rails were laid for the assembling of coal wagons to feed the staithe and to make room the old blacksmith’s shop and World War I ambulance sheds, afterwards used for oil lorries, were demolished. In the spring 1930, DHB had two railway tracks laid along Eastern Arm to the staithe. The up railway line ran underneath and the down line was on the seaward side of the giant staithe. In 1931 Southern Railway paid to have a low coal staithe built adjacent to Tilden Smith’s giant staithe.

Designed to load ships, the coal arrived by train and each wagon was upturned into one of the low staithees by a ‘tippler’. From the low staithe the coal was carried by a conveyor belt of steel 4-foot wide. The inclined belt raised the coal sufficiently high to be above the sidings and onto a specially designed apparatus the transferred the coal by the means of a telescopic to the holds of ships. It was designed to take ten hours to load 5,000 tons of coal and cost £22,000. The first ship to be loaded was the Kenneth Hawksfield that took on board 2,400-tons from Snowdown Colliery on 19 April 1932.

However, Southern Railway had made it clear that it was their intention was to use the Sea Front Railway for coal traffic at least 14 hours a day. This provoked a public outcry. In the event, a statutory restriction of 500,000 tons was imposed and the hours in use limited.

On 10 February 1931, the shipbreaking firm, C A Hill Ltd, was taken over by Messrs Peterson and Albeck of Copenhagen. In 1933, the Dover Corporation successfully sought to have their boundaries extended to include the Eastern Dockyard this came into operation the following year. At the same time, both the oil depot and the Submarine Cable Depot were extended. The demand for the car ferry service operated by Townsend continued to increase, even if cars were loaded on and off by crane. To meet this increase in traffic, the customs examination shed doubled in size in 1936. In the summer of 1939, Townsend’s carried 31,000 cars across the Channel.

That summer two 12-pounder guns were installed at the end of the Eastern Arm and the Camber was commandeered for the Royal Navy for motor torpedo boats, motor gunboats, launches and other miscellaneous craft. World War II broke out on 3 September 1939. During the Battle of Britain, on 27 June 1940, dive-bombers attacked the harbour and the pipeline was damaged. Oil leaked into the sea and caught fire and soon the 10,000-ton naval supply ship Sandhurst and other vessels were alight. The Sandhurst was full of torpedoes, ammunition and fuel oil. Dover’s police/firemen attended the scene, and persuaded the authorities to allow them to fight the fires. It took 12-hours to extinguish and the Dover firemen went with her to the Thames, still pumping out her holds. Captain Fred Hopgood, one of the Harbour Board tug masters, along with Dover’s police/firemen Ernest Herbert Harmer, Cyril William Arthur Brown and Alexander Edmund Campbell were awarded the George Medal for their part in saving several ships that day and the following two days.

Following the attacks on the harbour during the Battle of Britain, in the summer of 1940, the Camber pens were strengthened with steel and concrete. The 3-metre thick roof contained eight layers of reinforcement and weighed 23,000 tonnes. This was supported on a grid of large reinforced concrete columns that sat on large concrete caissons driven into the chalk seabed. A two-storey office block with quarters was also erected on the crosswall. For protection, on the flat roof there was a reinforced concrete pill box-cum-observation post with mountings for a light machine gun.

Operating from the Camber, throughout the War, was the Post Office Cable ship Alert. However, on 24 February 1945, while cable repairs were being undertaken off Dumpton Gap, near the North Foreland, the ship disappeared. With a crew of 60, many of which were local men, it is believed she was torpedoed. There were no survivors but their names are listed in Dover’s St Mary’s Church Book of Remembrance.

After the Germans had been driven from the Channel coast in late autumn 1944, Dover became a busy port of embarkation of men, munitions, railway engines and machinery. At the Eastern Dockyard, embarking jetties were built. At about the same time Dover Corporation drafted a plan for the future of the town that was, when Peace returned, embodied in the post-war Abercrombie Report.

The Eastern Dockyard was earmarked for industry and firms were encouraged to move in. Dover Industries Ltd opened a shipbreaking business and A.W. Burke, small engineering firm, made specialist parts for the British aircraft industry. Sunbury Cross Engineers Ltd and Whitecliff Works followed and in 1948, Parker Pens opened a large factory. The coal staithe was, by this time, in a poor state of repair but a decision on its future had not been made. The Post Office submarine cable depot in the Camber and the Shell /BP and Esso oil installations, for fuelling ships remained.

Next: Eastern Docks

- Published:

- Dover Mercury 27 June, 04, 11 & 18 July 2013