Up until the mid-19th century communicating over distances was fraught with natural problems such as the weather. At the time of the Armada (1588), beacons were used to transmit to London, Dover and elsewhere in the country that the Spanish had been sighted off the Lizard in Cornwall. During the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), peace was achieved on 25 March 1802 when the Amiens Peace Treaty was signed and, indeed Mayor George Stringer held a ball at his home, Castle Hill House. However, the Treaty only lasted a year and when Britain declared war on France a chain of semaphores was used between Deal and London to transmit the news.

In 1833, Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855) and Eduard Friedrich Weber (1806-1871) used copper wire to carry an electric current to a sensitive galvanometer, or current detector. They recognised that the movements, caused by electric signals, could be used as a code to pass messages. Adapted by Sir William Fothergill Cooke (1806-1879) and Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), the first electric telegraph for public use was established in 1837 along the Great Western railway from Paddington to West Drayton. This lead to the adoption of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) as the base for international time zones. The transmission wires, along the railway track, were supported on overhead poles as air is a great insulator of electric current. The ground, on the other hand, is a good conductor of electricity, particularly so when wet.

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791-1872) in America in 1838, demonstrated his Morse code in which varying combinations of short and long signals – dots and dashes – represented different letters of the alphabet and numbers. At about the same time he introduced the relay, an electrically operated switch by which a signal sent along the wire was strengthened at intervals, making long distant communication possible. Water, like the ground, is a good conductor of electricity so a good insulator was needed to prevent the electric current from leaking into the water. Morse insulated a wire with tarred hemp and in 1842 at New York Harbour, he successfully telegraphed through the submerged wire. Wheatstone successfully repeated Morse’s experiments in Swansea Bay.

Wheatstone had given evidence to the House of Commons two years before over the possibility of laying a Channel telegraph link between Dover and Calais. That year, 1840, he patented an alphabetical telegraph, or, ‘Wheatstone A B C instrument,’ out of which he developed his type-printing telegraph that he patented in 1841. This was the first teleprinter and printed a telegram in type using letters of the alphabet and numbers. These were on revolving hammers and were worked by two circuits, actuated by the current, that pressed the required letter on to the paper.

Charles Vincent Walker (1812-1882) had also been undertaking experiments with electricity and in 1845, the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) appointed him as the Company’s electrician. In that capacity, he had introduced Cooke and Wheatstone’s electric telegraph on the new railway line to Dover. Aware of Wheatstone’s experiment on underwater cables he tried various insulating materials to send submarine signals. It was already known that the emulsion exuding from an injury to the palaquium gutta tree, found in Malaysia, produced the emulsion latex that coagulated when exposed to air becoming rigid. However, gutta-percha, as it was called, also had insulating and adhesive properties. It was these qualities that those experimenting in submarine communication recognised.

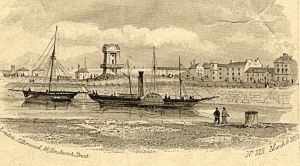

Folkestone harbour mid 19th Century where Charles Walker undertook experiments in the use of submarine cables for transmission. Dover Museum

To prove to the Company directors that submarine transmission was possible Walker ran several wires from Folkestone harbour to Copt Point, east of the town. These were soaked in different insulating materials, one of which was gutta-percha. Several days later, in front of the directors, Walker, with the help of his apprentices including John Francis Costello, attempted to transmit a telegraph signal through each of the wires. The wire soaked in gutta-percha was successful showing that it was possible to use a permanent cable to communicate with France.

John Watkins Brett (1805–1863) had also been perfecting underwater electric telegraph cable and an electric form of typewriter. In 1847, together with his brother Jacob, he obtained a decree from the French King, Louis Philippe (1830-1848), to establish a link between France and England. However, before they had chance to undertake such a project the revolution of February 1848 had forced Louis Philippe to abdicate. Later that year Louis Napoleon (1808-1873) declared himself president of France so John Brett set about persuading him of the virtues of telegraphic communication between France and England. Louis Napoleon eventually agreed to an experimental communication. Brett had already persuaded the British government to allow such an experiment to go ahead.

The Widgeon was a wooden paddle steamer that had been a mail packet on the Dover – Calais crossing before becoming an Admiralty survey vessel. In the third week of August 1850 the Widgeon, made several crossings of the Channel laying flagged buoys that marked the course of Brett’s experimental cross Channel cable. The steamer Goliath, during this time had arrived in Dover. On board was 30 miles of copper wire, a tenth of an inch thick encased in a coating of gutta percha 9/16 of an inch thick.

It was reported that it was a fine calm day with a favourable wind on Wednesday 28 August 1850. The Goliath, under Captain Beer with a crew of 30, accompanied by the Widgeon, under Captain Bullock, left Admiralty Pier. On board, besides scientists and engineers was John Brett. The ship followed the flagged course across the Channel, laying the cable. This was coiled around a large drum, 15-feet by 7-feet, amidships. The cable weighed five tons and the cylinder two. The last 300-yards of cable was enclosed in leaden tube to go over the ground on the French coast.

The cable was paid out at the rear of the ship and every sixteenth of a mile weights from 12lb to 24lb were clamped onto it to ensure that the cable sank. There was concern that the shifting sands of the Varne and the Colbert would prove a problem but in the event, this was not so. However, as the Goliath approached the French coast the wind started to get up.

Back in Dover, that afternoon, the children of the Pier District were awe-struck when they saw large crates, in which were batteries, being carried into the Pilots Tower. Then, at the nearby Town station, they saw a horsebox taken into a siding and were emphatically told not to touch the thick wire running from the Tower to the horsebox. A large crowd of children and some adults had gathered when a table, chairs and a large crate were taken into the horsebox. By the time Jacob Brett, Mayor Steriker Finnis, Charles Walker along with his young assistant Costello, and other interested parties arrived that evening, a large crowd had gathered. As well as the locals there were reporters who had arrived on the train from London. They were saying that an experiment was about to take place that was so incredible, it would change the world. On being told this, even the adults were awe-struck!

When the Goliath reached France the leaded end of the cable was taken on shore and at 20.30hrs. John Brett using the Brett printing machine sent the first telegraphed message across the Channel. It was in legible Roman lettering and was received by the apparatus, manned by Jacob Brett, in the horsebox. The message said: ‘The Goliath has just arrived safely; and the complete connexion of the underwater wire with that left at Dover this morning is being run up the face of the cliff.’ The first message from Dover to France was sent at 21.00hrs and, is said, to have been dictated by Mayor Finnis. ‘The Ancient Ports of Dover and Calais must be the great highway of communication with the whole Continent; in fact, the whole world!’

The exercise had cost approximately £2,000 but it was an epoch-making experiment of which the news quickly spread. Indeed, the Lord Warden, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), came over from his official residence at Walmer Castle the following day to inspect the apparatus at Dover. However, he was too late to send a message as fisherman, close to the French coast, had cut the cable!

In June 1851 John Brett along with Charles Fox – later knighted (1810-1874), Francis Edwards and Charlton James Wollaston, set up the Anglo-French Submarine Telegraph Company for the purpose of organising regular communication by sub-marine telegraph between England and France. He had already obtained, from the British government, monopoly rights for ten years and the French government readily agreed to the same terms. Work had started on improving the cable at the Blythe and Co. Submarine Telegraph Works, Wapping.

Sixteen copper wires were twisted into four wires, covered with gutta percha a ¼inch thick, and plaited by a machine in the manner of an ordinary rope around a shaft. Hemp yarn, having been previously soaked in pitch and tallow, was then tightly twisted around this and the hemp was overlaid with a series of six similar soaked hemp yarns. This was then covered with ten layers of galvanised wire, each one about ¼-inch thick. 25 miles of wire was made this way and having been rolled up was five feet in height, twenty feet in circumference and weighed approximately 20-tons.

The cable was loaded onto the Admiralty ship the Blazer under the command of Captain Bullock. Before this operation began, the ship’s funnel, masts, upper gear and boilers had been removed and by a laborious but cleverly orchestrated series of manoeuvres, the cable was moved from the factory and stowed into the ship. The whole operation took some 70 hours. The Blazer then left Wapping towed by two steam tugs to Dover.

Blazer laying the first submarine cable. Although the operation started from South Foreland, illustrators of the time showed Shakespeare Cliff in the background. Illustrated London News 01.10.1851

At 07.00hrs on 24 September 1851 the Blazer, accompanied by the two tugs, one lashed to each side, set out from the South Foreland to Cap Gris Nez. On board, as well as the cable and the engineering contractor Thomas Russell Crampton (1816-1888), were the four members of the Submarine Telegraph Company and a retinue of scientific engineers including William Cook and Charles Wheatstone. The ship had cast off from Dover harbour at 04.00hrs and on reaching South Foreland, near St Margaret’s the English end of the cable was taken ashore to a cave below the lower lighthouse. Here the communication apparatus had been set up and was attached. During the crossing, Charlton Wollaston supervised the lying of the cable and even though a number of problems were encountered, each was satisfactorily resolved. That is until one of the tug’s ropes parted and the wind and tide carried both it and the Blazer off course. By the time another tug, that was behind in case of such an occurrence, could be attached, the Blazer had gone about 1½ miles from the given course.

With the tug re-attached, the journey progressed slowly but at 18.00hrs, when the Blazer was about three miles off Cap Gris Nez, Charlton Wollaston calculated that there were only 2½miles of cable still on board. By this time, the seas were getting rougher and it was decided to go no further. On the following afternoon, the Blazer was towed as far as the cable would reach and this was secured to a buoy. To the end of the cable a coil of gutta percha was temporarily attached and run to the shore. Eventually communication began. In the meantime, connections had been made from South Foreland to a temporary office of the Submarine Telegraph Company under the Castle walls. There, in an upper room, the wires were attached to the various items of telegraphic apparatus but when the fuses were connected, there was an ‘explosion.’ This, both Jacob Brett and Charles Walker expected but it caused alarm among the dignitaries in the rooms below and someone shouted ‘fire’ and then there was panic!

The following morning, for Brett and Walker, there were a few anxious minutes and then communication was made and signals were interchanged with Calais. The Lord Warden, the Duke of Wellington, was at a meeting with the Harbour Commissioners in the then Harbour House in Council House Street in the Pier District. He was due too catch the 14.00hrs train to London and it was agreed that a signal from Calais would trigger a gun to fire a salute from Western Heights when the Duke’s train left. The signal was sent and the loud retort reverberated around the town and caused a ‘tidal wave’ in the Bay! A 32-pounder had been loaded with ten pounds of powder and a ball had been fired by a signal from Calais into Dover Bay!

Within a few days, the temporary length of cable was replaced and when a number of other problems were sorted out, great celebrations were held in both England and France. A portion of the coil was placed in the Calais museum next to the balloon that aeronauts Blanchard and Jeffries had used to make the first aeronautic crossing of the English Channel. The Black Eagle, under the command of Captain Hutchings towed the Blazer back to Wapping and all augured well. Unfortunately the weather deteriorated and by the time they had reached Margate the Blazer, not having any ballast, was tossing about so much that Captain Bullock and the crew had to be taken off.

On 13 November at 13.00hrs, the Submarine Telegraph Company opened their office to the public at 30 Cornhill, London and during the afternoon, a number of distinguished visitors called. Most were particularly interested in the communication room that was upstairs. There was a Wheatstone printing machine also Brett and Morse machines and a machine invented by Frenchman, Louis François Clément Breguet (1804-1883). All were in direct communication with Paris. The Brequet machine was of particular interest as the printout was in semaphore as this was extensively used in France and the French government were concerned that the new telegraph system would throw many of their semaphore communication employees out of work. Machines using Morse code were favoured in England and it was these that were to be used until teleprinters came into regular use.

By November 1852, the Submarine Telegraph Company together with the European and American Telegraph Company had laid down wires along the turnpiked roads from London to Dover (A2), where they were connected to the submarine cable and in France, connected with the cable to Paris. On the first day all the connections were made the French transmitted that the weather was, ‘Foggy in Paris and Overcast and dull in Arras.’ The British replied, ‘May this wonderful invention serve under the Empire to promote the peace and prosperity of the World!‘

May 1853 saw the iron screw collier William Hutt arrive in Dover carrying 70 miles of cable that was laid between the cave at St Margaret’s and Middlekirk on the Belgium coast. The William Hutt was helped by two Admiralty packets, Vivid, under the command of Captain Luke Smithett and the Lizard under the command of Captain Washington. On completion, a message was sent to the Company office at 30 Cornhill, London announcing the success of the project.

During the next ten years, submarine cables were laid between England, Ireland and the Continent. The 500-ton wooden paddle steamer Monarch, launched in 1830, was the main ship used. Soon after, many of the countries and islands in the Mediterranean were linked by cable and plans were put afoot to join Britain with the United States. In 1856, the Atlantic Telegraph Company was formed but the connection was not achieved until 1868. Two years later a cable was laid between Egypt and India and the laying of that cable played a significant role in the British dominance of World trade.

In Dover, the Submarine Telegraph Company opened an office at 7 Clarendon Place, not far from the Town Station, and the Superintendent was John William Edwards. The station had their own telegraph machine, manned by John Costello, and both the military establishments at the Castle and on Western Heights had machines. On 15 May 1855, the Great Bullion Robbery took place on the London Bridge – Dover, South Eastern Railway Company train. The telegraph system was used extensively in communicating between the different bodies involved in both England and France and so helped in catching and bringing to justice the perpetrators.

The cross Channel shipping industry were also quick to recognise the importance of the telegraph especially if decisions were to be made as to delaying a crossing due to adverse weather conditions. However, submarine telegraph cables were vulnerable to damage and on the night of Monday 5 January 1857, during a storm force 10 a 700-ton heavily laden ship lost her anchor in the Downs. Driven by wind and tide she was in danger of colliding with a schooner whose crew let the anchor play out. 40-fathoms of the schooner’s anchor chain had been released, when the ship suddenly came to a halt. This was sufficient to lessen the impact.

In Ostend, Captain Edmund Lyne of the 293-ton, 128 horsepower Channel packet, Violet was trying to communicate with Dover by telegraph because of the wind and sea conditions and poor visibility. The Violet was carrying the mail and the Captain needed prermission from Dover to delay departure. As the telegraph line was dead, the Captain was obliged to make the crossing and the Violet cast off at 20.30hours with a crew of 17, a mail guard and the one passenger. She never arrived in Dover. Meanwhile, the schooner as quickly as she had come to a halt suddenly swung round and was careering forward at great speed when, for the second time, she came to an abrupt halt. She eventually broke away and came to grief by which time her crew had taken to the lifeboats.

The wreck of the Violet was found on the southern spit of the Goodwins the following day. Captain Luke Smithett sailed in the Empress to investigate and found the vessel, sitting upright in the sand, without her funnel. Doors and part of the decks and bulkheads were missing. The bodies of three stokers were recovered, as well as mailbags. Further investigation found that the schooner’s anchor had fouled both the Ostend and Calais telegraph cables. It took a month to make repairs at a cost of £1,627.

A submarine cable was laid between Boulogne and Abbots Cliff, to the west of Dover, in 1859 and in 1860 the National Signal Station Company, part of the Submarine Telegraph Company, were operating from the Company building at 7 Clarence Place. Their advertisement stated that they communicate with shipping by flag semaphore and signal lamp blinkers, by the use of telegraph, to ship owners, Lloyds Insurance and any persons interested. Nationally the number of telegraph companies had escalated and the British Government, in order to gain control, in 1868 voted to nationalise the service under the Post Master General. The Act was extended two years later, in 1870, and made it clear that the Submarine Telegraph Company would not come under the Post Office.

The engineer in charge of the Submarine Telegraph Company in Clarence Place at this time, was John Bourdeaux. He was a major promoter of telecommunications and gave frequent lectures and mounted exhibitions, particularly at the Dover Working Man’s Institute, in Biggin Street. In January 1878, Bourdeaux took a party of local dignitaries that included the Mayor of Dover, Percy Simpson Court, to the telegraph cave at St Margaret’s Bay. There, he explained to the assembled throng, how the submarine telegraph worked and then he took out of his bag two instruments of polished mahogany that looked like ‘champagne glasses without stems.’ After sending a telegraph message to Calais, he then disconnected some wires and replaced them with wires from the mahogany instruments. Within minutes, he was talking into one of the wooden instruments holding the other to his ear. He passed these over to the Mayor who started to sing Auld Lang Syne! Bourdeaux shushed him so they all could hear the telegraph man in Calais singing the same song! Bourdeaux had successfully demonstrated submarine telephone communication.

Telephones had simultaneous been invented by Graham Alexander Bell (1847-1922) and Elisha Gray (1835-1901). Both filed their patents on the same day – 14 February 1876 – but as Bell got there first he was given universal credit. The following year Thomas Edison (1847-1931) developed his variable-resistance carbon transmitter and the modern telephone was born. Like the telegraph at that time, the telephone needed wires to communicate and so in Britain, the telephone came under the same body as the telegraph, the Post Office.

The price of telegrams to the Continent was a concern, especially the amount paid by the Post Office to the Submarine Cable Company. Henry Raikes (1838-1891), Post Master General (1886-1891) replied to a question in the House of Commons in March 1887, that during 1886, on account of these lines, £37,906 had been paid by the Post Office. He added that the total earnings of the joint arrangements between the Post Office and the Company had netted £132,229 for the same period and this was shared equally. In France, the Administration des Postes et Télégraphes had taken over the post and telegraphs with the Submarine Cable Company concession up for renewal in 1889. The Company felt that a new concession would not be as favourable as before and the Company opened negotiations with the British Government.

In February 1888, the Government agreed to buy the two cables between England and Belgium, the four between England and France, and one between Jersey and France. They also purchased the Company’s repair ship, the Lady Carmichael and their buildings in Dover, Ramsgate, Beachy Head and Jersey. The transaction cost the British Government £67,163 and they officially took over on 1 April 1889. The South of England Telephone Company had introduced the first commercial telephone to Dover in 1888, and with the expertise of John Bourdeaux, the company established a permanent telephone link between Dover and Calais the same year.

Lady Carmichael Paddle Steamer was converted to cable laying and renamed Alert in 1889. Dover Museum

The wooden paddle steamer Monarch, which had been used for both laying and repairing marine cables by the Electric Company, was taken over by the Post Office following the 1870 Act. Soon after she broke down and was replaced by a purpose built ship, also named Monarch. When bought by the Submarine Cable Company the 760-ton paddle steamer, renamed Lady Carmichael after the Company chairman’s wife, was converted into a cable ship to repair the telegraph cables. Following the takeover, she was renamed Alert and kept in the Granville Dock.

Over the following decades, considerable advances took place in telegraph communication. William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (1824-1907), invented the ‘Recorder’, which traced the message in code on a strip of paper. Alexander Muirhead (1848-1920) invented the automatic transmitter and then, in 1901, Sidney George Brown (1873-1948) designed the first automatic cable relay. This received signals from one section of cable and reinforced them before transmitting them to the next cable section. In 1875, Duplexing, permitting simultaneous operations in opposite directions on the same cable, was introduced. However, submarine cable breaks remained a huge problem.

Dropping a marker buoy to show the start of a line that is being examined for a fault. Alan Sencicle Collection

Up to this time, it was necessary to raise the whole of the cable from the sea bed, which by the sheer weight could cause another break. To get round this the cutting and holding grapnel was invented. The grapnel would be lowered from the ship to pickup the cable from the seabed and raise it to the surface. The cable was then cut and tested to find out on which side the fault lay. The ‘good’ end was sealed and buoyed. The faulty end was placed over the bow sheaves and as it was wound through, it was constantly checked until the fault was found. The faulty part was removed, good cable was spliced in and then the repaired cable was attached to the buoyed cable. Checks were then made to ensure that the cable was working again.

Laying a direct line between London and Paris was the next stage in the evolution of the telegraph system and this took place in 1891. The total distance was 271 miles and it was decided to adopt a loop circuit, which meant that the amount of cable needed was 542 miles including 42 miles of submarine cable. There were two separate lines with a common cable and four conductors belonging to both the English and French governments. Across land, the wires were carried on poles 30-feet above the ground, the English landlines were of copper wire and every mile weighed 400lb. The French used copper that weighed twice as much.

The connecting submarine cable consisted of four insulated wires each made up of seven copper wires and weighed 160lb. This was coated with gutta percha wrapped in tanned hemp and sheathed with 16 galvanised steel wires each 0.28-inch thick. The cable with a breaking stress of 3,500lb, was made by Siemens Brothers of Woolwich and laid by the new Monarch. The new cable joined the 14 cables that were already across the floor of the English Channel and there were two more running along its length. Three years later in 1894, at the Union Jack Bazaar held in Dover’s Town Hall, the Dover Postal Telegraph staff were operating telegraphic apparatus that could convey 400 words a minute. At the Castle and on the Western Heights, the military had introduced electric searchlights, telephones and improved telegraph communications. The station on Western Heights station was called Spion Kop and eight personnel under the command of T Wallace, the Chief officer, manned it.

Upper South Foreland Lighthouse above the Submarine cable cave, where Guglielmo Marconi conducted his experiments. Dover Museum

January 1895 saw the twenty-fifth anniversary of the nationalisation of British telegraphs and although telephones were making in-roads into the telegraph market, as they both came under the nationalised post office, they used the same wires. That year 71,465,000 inland, press and foreign telegrams were sent through 32,831 miles of lines. The lines were made up of 206,304 miles of wire, the number of instruments in use was 8,500, the speed rate was between 70 to 600 words a minute and the average charge for an inland telegram, by the Post Office, was 7 pence and three farthings. However, in 1899 at the upper South Foreland lighthouse, on the cliffs above the submarine cave, Gugliemo Marconi (1874-1937) demonstrated his revolutionary new technique of communication – a wireless telegraph. Messages, during the experiment, were relayed between Connaught Hall and Wimereux near Boulogne.

By 1898, the Submarine Telegraph Department had moved to North Yard Quay and W R Cuffey was the Superintendent. His assistant was F Pollard and the Alert was moored nearby. Ten years later the Submarine Telegraph Department Superintendent was F Pollard and the town boasted of 13 telegraph offices! On 12 May 1913, at the age of 82, the oldest telegraphist in the world, John Francis Costello died. He lived at 2 Osborne Villas, Elms Vale Road and before retirement had been with South Eastern Railway for 61years. As stated above, he was Charles Walker’s young assistant in the horsebox at Town Station on Wednesday 28 August 1850!

During World War I (1914-1918), the submarine telegraph came into its own, especially for communication between the military based in the UK and those on the Continent. In Dover, the scouts took over the role of the telegram boys delivering messages fast and efficiently. They were also in charge of guarding telegraph and telephone routes, reporting when any wires were down. However, at sea, the crew of the Alert faced a new problem, the necessity of building bypasses around sunken torpedoed ships that were laying across cables they had broken when sinking. The Alert crew also had to run the gauntlet of torpedo attacks. In 1915, the first cable ship Alert was sold out of service and was to be replaced by a pre-ordered new purpose built ship. However, following the sinking of the Monarch by a torpedo, the new ship took her name and duties.

The second cable ship named Alert based in Dover came into service in 1918. She was built by Swan, Hunter and Wigman Richardson, 941-ton twin screw, 196-foot in length with a beam of 31-foot and a draught of 20-foot and designed to operate in shallow waters only. Her 105 horsepower engines gave her a maximum speed of 10.5 knots. The new Alert was constructed from steel and had a clipper stem with cable sheaves and a cruiser type stern. She had three cable tanks of 10,160 cubic feet capacity that could hold up to 81 miles of single core cable, 54 of 4 core or 35 of 6 or 7 core. Originally, she was coal-fired, but was converted to oil fuel in 1920. A year later, her archaic second-hand cable gear was replaced.

The General Post Office (GPO) moved their Submarine Divisional Telegraph station from the Western Docks to a purpose built depot on land belonging to the Admiralty in the Eastern Dockyard in 1921. Nearby, in the Camber, the Alert had her own mooring. The British telegraph service received a special recognition on 23 April 1924 when King George V (1910-1936) formally opened the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, London. From the stadium, a special line was laid and when the King declared the Exhibition open his message was transmitted by the Atlantic submarine cable to Halifax, Nova Scotia. From there around the World through as many routes as were available until it returned, by the cables under the Channel, back to London. Automated working was employed throughout so as the message came in to each telegraph station it was pushed on without any manual intervention. 80 seconds after the message was sent it, had gone round the World. A telegram boy delivered it to the King!

The submarine cables to France were re-laid in 1930, coming ashore at St Margaret’s bay beach. In 1932, a large repeater station was completed on Bay Hill, St Margaret’s Bay. The French purchased one of the cables from a German company as part of the reparation account. In 1926, one of the cables had been re-laid to Holland and was of Dutch manufacture. Otherwise the entire submarine cables around Great Britain were of British manufacture. Concerning receiving and sending telegraph messages, Britain appeared to have fallen behind other countries preferring automated Morse apparatus to the teleprinter. By the 1920s the teleprinter was in commercial use and the GPO considered switching over but the state of the country’s economy slowed this down. Nonetheless, in 1932 teleprinters, operated by superposed trains of waves of tonic frequency transmitted over telephone circuits, were introduced.

As the clouds of World War II (1939-1945) were gathering in the late 1930s, the Defence Telegraph Network (DTN), later called Q, was set up. This was to provide a communications network for the Armed Services separate from the public telephone. At the outbreak of War, many of those involved in telecommunications and adept at using Morse apparatus were drafted into the Armed Services and in the Army, the Royal Corps of Signals. The Alert remained on station in Dover, going out, often under enemy fire and torpedo attacks, repairing broken cables, creating bypasses when cables had been cut by sunken torpedoed ships and undertaking many jobs that she was never originally designed to do. For instance, she replaced German cables in the eastern end of the Channel with anti-submarine cables and in 1942 helped to lay an oil pipeline. Siemens, in conjunction with the United Kingdom Physical Laboratory, adapted submarine cable technology for Operation PLUTO – an oil pipeline to Continental Europe. Following the D-Day invasion of June 1944, the Alert laid the (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) between Dungeness and Ambleteuse, north of Boulogne in the Pas de Calais.

Following the retreat of the Germans from the Pas de Calais, the bombing and the shelling of the town ceased and Dover became a busy port of embarkation. Reinforcements of men, munitions and machinery of war were sent to parts of Europe still under occupation. This meant that the menace of war was not far away. In February 1945, a cable break in the Dumpton Gap – La Panne No2 phone cable was reported off the North Foreland and the Alert went to investigate. What happened next is unknown, only that on 25 February 11.05hrs, some 30 hours after the last communication, evidence of the wrecked Alert was found. All the crew of 54 plus 6 gunners were lost, many were Dover men.

The following is the official list of those who lost their lives:

J G B Oats – commander; E G N Dellow and J Dixon, second officers; J C Stivey, third officer; J C Taws, fourth officer; H C Fisher, chief engineer; E Prince and J Cassingham, third engineers; R A Robinson, fourth engineer; J G Millar, ships doctor; H T Cronin, purser; N A MacLeod, wireless operator; H Bates, chief steward; W Smith, cable foreman; H W O’Beirne, assistant cable foreman; W E S Shepherd, boatswain.

W G Shelton, D C Phillips, F A Drury and A Gregory, quartermasters; A Insole, seaman cable joiner; F S Everall, F S B Baldwin, F S G Sharp, W F Cornwell, WTC Hunter, A V Godden, G H Jones, J C Brookshaw, P W Ellis, R S Button, FA Gilchrist, G R Peters, H F Hurford and G H Millard seamen cable hands.

W J Tickner, chief cook; F W Payne, second cook and baker; R C S Wakefield, second steward; L S Martin, FW Cant, A K J Kitt, R F Blamey, E J Smith and F H Williams assistant stewards; F A Hampsall, carpenter; W J Maple, donkeyman; C J Dowle, storekeeper, F Hope, cable engine driver; W J King and V W Mackay, leading stokers; R E Booker, E J Demellweek and A G Wade, stokers; L C Voss, assistant engineer.

Gunners R.N. – S Heale, H W Bunting, M Campbell, F W Rivett, F Clarke, R P Stoyle.

St Mary’s Church, Cannon Street where those who lost their lives on the sinking of the Alert cable ship, off Dumpton Gap in February 1945, can be seen. Alan Sencicle 2009

The bodies of J Dixon, H C Fisher and J C Taws were found on an Alert raft that came ashore near De Hann, Belgium some days later. They were buried at Oye Plage cemetery. Norman MacLeod’s body was recovered from the sea and buried at Calais. Although there is no memorial to those lost on the Alert in Dover, their names are listed in Dover’s St Mary’s Church Book of Remembrance. Two months after the Alert was lost, the Monarch was sunk off Orfordness, on the Suffolk coast, but luckily 69 of her 74 crew survived.

After the tragic loss of the Alert, the cable layer Iris was based in Dover until 1947 when the twin-screw Ariel took her place. Built in 1939 by Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson the Ariel 1,479-ton had a length of 251-foot 8-inch, breadth of 35-foot 3-inch and a draught of 16-foot 4-inch. She had triple expansion engines of 1,400 i.h.p. giving a maximum speed of 12 knots. Although based in Dover to maintain the cables in the southern North Sea – Dover Strait area she was also called upon to repair cables further a field, from Norway in the north to Gibraltar in the south.

On the 1 October 1969, the GPO ceased to be a Government department but beyond the prefix H.M.T.S. Ariel changing to CS, nothing much else happened. The future of the Ariel at Dover was assured, indeed in 1974 it was said that she would be involved in laying a proposed a new generation undersea telephone cable between Britain and Belgium that would be capable of carrying 4,000 telephone calls simultaneously. There was also talk of laying optical fibre cables, made up of strands of glass each finer than a hair that would increase transmission capacity a million fold.

At Eastern Docks, the number of passengers and their cars passing through Dover to the Continent was escalating and freight traffic was also increasing. At Southampton, a new Post Office Central Marine Depot was being created and it seemed logical to Dover Harbour Board that if the Cable Laying facilities moved to Southampton, there would be room for new freight berths. Pressure was put on the GPO and as a spokesman for the Marine Division was reported in the local press, as saying, ‘It is with great regret that operational necessity has compelled so many to tear up roots – cultivated so long in this port. The association between Dover and the Post Office has always been happy.’

Ariel cable ship in the Camber 1959 in front of the two oil tanks, the offices are to the left. The two cross Channel ships are Maid of Kent nearest the quay and Lord Warden on the outside. Dover Harbour Board

The departure of the cable vessel CS Ariel was at 16.00hrs on Thursday 2 January 1975. This brought to a close a significant chapter in Dover’s, Great Britain’s and the World’s history that had lasted for some 125 years. Shortly after the Ariel sailed away the cable depot building was flattened and made into a lorry parking area. The Ariel was withdrawn from service and scrapped in 1976. Her earlier Dover berth in the Camber has more recently been replaced by ferry check-in booths.

- Presented:

- 20 December 2014

Useful sites:

- British Telecom Heritage and Archives: http://www.bt.com/archives

- Telegraph Museum Porthcurno: http://www.telegraphmuseum.org