On 27 January 1844, the South Eastern Railway Company’s (SER) line from London, via Folkestone, to Dover was completed and the 2-2-2 steam locomotive number 36 Shakespeare, made a trial run. At 16.00hours on Tuesday 6 February, a shrill was heard from the Shakespeare engine pulling four carriages. On board was the chairman of SER, Joseph Baxendale 1785-1872), along with the directors and they came into the Town Station in the maritime Pier District of Dover. A multitude including dignitaries was there to great them, for this was the first train ever to come to Dover. The next day the railway opened to public traffic and according to the Railway Times of 24 February, six trains a day were provided in each direction.

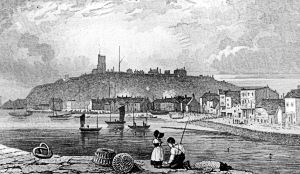

Given Royal Assent on 21 June 1836, the Act to build the line required that SER and the Brighton Railway Company used the same line from London Bridge to Redhill. From Redhill through Tonbridge to Ashford the line was almost, and still is, straight. From Ashford to Folkestone it is relatively straight but from Folkestone to Dover there are the cliffs on one side and the sea on the other. As dealing with these problems was going to be costly the company decided to abandon the idea and buy and refurbish Folkestone harbour as their terminal for cross-Channel ferries to France. They took the line across a viaduct at Folkestone, which can still be seen today, to the harbour where they built a station.

The Dover Corporation and Harbour Commissioners put pressure on the railway company to with the Act and the line was carried through to the town. Tunnels were excavated through the cliffs and Round Down Cliff was demolished. For the journey from Shakespeare tunnel to Archcliffe tunnel the track went along a platform of earth that was laid alongside Shakespeare beach. Town Station was close to Dover’s harbour, which at that time was on the western side of the bay. On 2 April 1848 the foundation stone was laid for the Admiralty Pier, jutting out to sea on the west side of the harbour and even while it was being built it became the main quay for cross-Channel ships to Dover.

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1808-1873), who had been elected President of the French Republic, staged a coup d’état on 2 December 1851, and became the country’s sole ruler. A year later, he declared himself Emperor Napoleon III and introduced a number of reforms one of which was modernising the French banking system. This made France financially attractive and gold started to flow from London to Paris. Thus, besides carrying passengers and goods SER was increasingly carrying gold.

The Robbery

On the evening of 15 May 1855, three boxes of gold were delivered to London Bridge Station by John Chaplin of Messrs Chaplin & Co. – security conveyance. One of the boxes contained gold belonging to Messrs Abell & Co., a second to Messrs Spielman & Co. and the third Messrs Bult. All the boxes were sealed, weighed and entered on the manifest at Chaplins before being transported to the station – Abell’s was the largest and weighed 2,125½ ounces.

On reaching the station, they were unloaded and with the help of bullion porter James Sellings, John Chaplin took them into the stationmaster’s office. Edgar Cox, the clerk there, weighed and signed for the bullion. Cox, Sellings and porter John Bailey carried the three heavy packages into Superintendent Weatherhead’s office where senior clerk, William Tester put the bullion into two iron chests. The company had four of these chests, each had two Chubb locks with two keys fitted all four. At London Bridge, one of these keys was kept in Superintendent Weatherhead’s office and this Tester used to lock both chests. The other key was kept in the stationmaster’s office and this Cox had brought with him for the other locks. The two chests were then wheeled into the strong room.

A few minutes before the mail train was due to leave, at 20.30hrs, the chests were wheeled out by Tester and with the help of train’s senior guard, James Burgess, they were put into the brake van. This was behind the engine of the train where, except at each station, the senior guard remained. Bullion was only carried on the mail trains and the brake van was designed with this in mind. Trains did not have corridors in those days and the design of each carriage was based on a coach.

The under guard was in the rear coach and it was his duty to help passengers on and off the train, check doors were closed, check that the red lights at the back of the train were lit and wave his flag to the senior guard when all was done. At the stations the senior guard stayed close to the brake van and when under guard waved his flag, the senior guard who blew his whistle to tell the driver he could carry on. The under guard that evening was John Kennedy.

It was SER Company policy that the senior guard was not allowed to have anyone in his van. Along with the gold consignment, there would be other goods, packages and cases belonging to passengers travelling on the train or sending their goods by train. The guards worked to rosters that were compiled by the deputy superintendent or a senior clerk in the superintendent’s office. At the time of the robbery this was Tester’s job. The guards were only allowed to work on the mail train, at the most, once every three months and the senior and under guards were not allowed to work regularly together on the mail train.

At Folkestone, the iron chests were unloaded but only unlocked if anything was to be taken out for collection or put in at the port. If not, the chest would remain locked and at least one member of staff was designated to stay with the chest until the cross-Channel ship berthed. As there were two chests on the night of 15 May, watchman Spicer and telegraph clerk, Robert Mackay were given the task with porter Richard Hart as relief. Police Constable James Knight relieved them on the morning of 16 May.

That morning four seamen took the two chests on board the Lord Warden steamer, built by Laird Bros in 1847, where they were left in charge of Captain James Golder. On arrival in Boulogne, the Captain unlocked the chests and Jaques Feran, porter at the customs office took the three packages out of the chests carrying each separately into the customs office at the French port. On picking them up, he commented to the ship’s Captain that none of the packages appeared secure. The Captain inspected them and noted this in his log.

James Major of the Messageries Imperiales at Boulogne took charge of the three packages and they were weighed in the custom house. The weights did not correspond to the manifest – the one belonging to Abell’s was found to weigh 40lb lighter, Bult’s was slightly heavier and Spielman’s was much heavier.

Major took them into his own office and again weighed them but the weight was the same as at the custom house. The packages were loaded into similar chests as in England and again locked but Major decided to travel with them to Paris. The first package, from Messrs Abell & Co., was delivered to M. Everard of Everard and Co. and when opened was found to contain lead shot. The other two packages also contained lead shot although the smaller one, Bult’s, did contain some gold.

After leaving Folkestone, the train carried on to Dover where it terminated at the Town Station. That evening there were two members of staff on duty, porter and booking clerk Henry Williams and porter Joseph Witherden. The latter was young, clumsy and according to Williams, lazy. Williams had sent Witherden off to help passengers with their luggage from the Ostend boat and should have returned by the time the mail train came in but he was nowhere to be seen.

In fact, he did not return to Town Station until the last passengers from the mail train were leaving. He told Williams that he had been waiting in the customs shed for passengers to come off the boat but there were none. Angry, Williams gave Witherden a dirty menial task to do while he, along with the two train guards, Burgess and Kennedy, enjoyed a pipe and a cup of tea in the booking office.

There were two passengers booked onto the mail train’s return journey to London. This was due to leave at 02.00hrs but about twenty minutes before two men came into the station. One was shorter than the other with fair hair and clean shaven. The second, older man was taller with black hair and whiskers. Both were carrying heavy carpetbags and wore short caped coats. They walked through the barrier towards the stationary train and Williams was about to leave his office and tackle them over their tickets when Witherden appeared. He asked to carry the shorter man’s bag, checking if Williams was watching him doing his duty.

The shorter man refused to let his bag go and this surprised Witherden, who already had hold of the handle. The ‘gent’ was then rude to Witherden who did let go but demanded to see their tickets. The dark haired man produced two blue first class tickets from Ostend to London. Looking at these Witherden said that there had been no luggage passed through the custom house that evening from Ostend to which the fair-haired man replied ‘No, we came yesterday.’ and gave Witherden a shilling!

The Investigation

On receipt of the telegraphic news from Paris announcing the robbery, two police officers, Sergeant Smith and Sergeant Thornton, from Scotland Yard London, were despatched to France. There they saw James Major of the Messageries Imperiales at Boulogne and the three bullion dealers for who the gold was intended. The lead shot was identified having been made in England and this together with the discrepancies in the weights on the manifests convinced them that the robbery had taken place between London and Boulogne.

On returning to London the officers inform the directors of SER but they were of the opinion that the robbery had taken place after the gold had left their jurisdiction. This had been told to Abell’s who immediately started legal action against the French railway company. With the fear of legal action, SER arranged for their solicitor, Mr Rees, to be co-opted onto the core investigation team. The fourth member of the team was Metropolitan detective F Williams.

On looking at the evidence brought from France even Rees had to admit that the robbery had taken place between London and Boulogne. Within a week of the robbery, a man named Seal drunkenly boasted that he had executed the robbery when the gold was being transported to London Bridge Station. He was arrested but it was found that Seal, who ran a betting office, was given to such boasting and was subsequently released.

The four investigators called a meeting that included representatives from the SER, Metropolitan, Folkestone and Dover police forces. They told them that it was believed by the directors of the SER that the robbery had taken place in France. However, to have the full picture of the transhipment they wanted everyone who was in anyway connected with the gold, the train, all the railway stations the train stopped at – including Dover – and the ship to be interviewed. Following the meeting, as the investigators were given the names of all those directly connected with the shipment, they had them put under the surveillance of officers from Scotland Yard.

At Dover, Police Superintendent Coram was the senior police officer. He had been a sergeant in the Metropolitan police and knew the core-investigating police officers. Coram personally took charge of the investigation within the town including interviewing Henry Williams and Joseph Witherden. He flagged up Witherden’s statement about the two men who arrived twenty minutes before the 02.00hrs train carrying heavy bags. With this in mind, he gave out the description provided by Witherden and sent his men to every pub, hotel and guesthouse near to the station to see if anyone recognised them.

Robert Clark, waiter at the Dover Castle Hotel, 6 Clarence Place, said that the two men answering the description came to the hotel about midnight on 15 May, carrying heavy bags. They ordered brandy-and-water to be served in a soda water bottle, which he thought was odd. Widow, Mrs Elizabeth Divers, the owner of the hotel, found such a bottle and took a look at the two men before going to her bed. Clerk took a further order for drinks, which the men drank before leaving at about 01.30hrs.

A couple of day’s later Werter Clark, the keeper of the Rose Inn, Cannon Street, called at the police station to see Superintendent Coram. Having heard of the investigation, he said that back in October 1854, two men answering the description of those the police were interested, stayed over night. They gave their names as Adams and Peckham. During the evening, they were joined by a third man, who was known to Werter Clark as Burgess – a railway guard – who frequented the Rose. The next morning Adams and Peckham left after breakfast inquiring the way to Folkestone saying that they would walk. Clark pointed the way over Western Heights.

In London, SER Directors were proving a constant constraint, not only did they firmly believe that the robbery had taken place in France, they had great confidence in the train guard, James Burgess. Only with great deal reluctance did they allow him to be interviewed. Burgess was in his early thirties, lived in London near the station and had ‘remarkable self possession.’ He denied all knowledge of the robbery but did admit that sometime he allowed ‘gents‘ to ride with him in the brake van. He was emphatic that on the night of the robbery he was on his own throughout the journey. Further, he pointed out to the investigating officers that the driver and fireman could see into his van from the engine.

As the interview was about to finish, Burgess raised the possibility that the chests could have been broken into while waiting on the quayside for the ship to take them to France. he had seen the telegraph clerk, Robert Mackay, chalk the time of the ship on the side. Although those assigned to look after the chests, said Burgess, may have been vigilant, they could have fallen asleep and when the robbers saw their chance, they took it. The four investigators had already decided that it was not an opportunist robbery but told Burgess that they would bear in mind his observations. One of the police officers assigned to watch Burgess noted that he was frequently in the company of William Tester, the senior clerk in the Superintendents office.

William George Tester was in his mid-twenties, well educated and was always smartly dressed. He wore a distinguished trimmed moustache, bushy black whiskers and had a military bearing. Tester had started as a clerk with SER at Folkestone before being promoted to stationmaster at Margate. There he met Elizabeth Page and they had married in early spring 1855, a few weeks before the robbery. He had been promoted to London Bridge in 1853 and the couple lived in Lewisham. Tester was also highly thought of by the directors of SER and while the investigations were on going they gave him an exemplary reference for a more senior position. This was in Stockholm with the Swedish Railway Company and he took up the position in September 1855.

Besides dealing with bullion and other valuables following their arrival at the station, part of Tester’s duties was to arrange the roster for the railway guards. He was given this job after returning from his honeymoon as the deputy superintendent, Mr Finnegan, had left. Company policy was that guards only travelled on the mail train once every alternate month and the senior and under guards were not to work the same trains on a regular basis.

Albeit, it was noted by the investigating officers that Burgess had worked the mail train almost every evening for the two months prior to the robbery and John Kennedy was frequently the under guard. John Kennedy’s journey book confirmed the officers’ observations and when interviewed he said that on the night of the robbery the only odd thing he noticed was at Reigate. There, Kennedy said that he thought, because it was dark but the oil lamps were lit, that he saw Tester leaving the train. If it was Tester he was carrying a dark bag but it may not have been him as Tester lived in Lewisham so had no reason to be on the train.

Police Officer W Dickinson was on duty at London Bridge on the night of the robbery and described the various passengers that came in on the Dover mail train. This included two men carrying what appeared to be heavy shoulder bags. He was adamant that they did not have carpetbags and it was their behaviour at the cab rank that caught his attention. The fair one, PC Dickinson said, was younger and shorter than his dark haired companion was and he offered to get them a cab.

They declined instead they walked down the rank and appeared to be walking away from the station. However, when they seemed assured that the police officer had disappeared into the station they returned and took the first cab in line. PC Dickinson noted the cab number and on its return the cab driver told him that he had taken his fare to Hampstead Road, London.

After hearing of the robbery Mr Chubb, the locksmith, contacted SER. Interviewed by Mr Rees, the solicitor on the investigating team, he said that in June 1854 his company had been asked to change the locks on two of the chests as they had seized up. The letters were written in William Tester’s handwriting and signed by the then Superintendent a Mr Brown.

Others that came forward included a Mr Bailey from the Bank of England. He told the team that on 28 May 1855 a tall, fair-haired man with a northern accent brought 600 sovereigns into the bank and asked for them to be exchanged for six £100 notes. The man said that Messrs Edginton of the tarpaulin manufacturers of Duke Street, had sent him.

The company were frequently employed by SER but the senior teller was none too happy about the transaction. He therefore made a note of the numbers of the £100 notes – 45,420 to 45,425 inclusive – and all were printed on 9 January 1855. After the man left, Mr Bailey contacted Edginton’s who knew nothing of the transaction. Hence, he issued an order stating that when the notes came back to the Bank a note was made as to who endorsed them.

One of the notes, 45,422, was presented for exchange for 10x£10 notes on 10 September 1855 , it was brought in by William Tester’s father. George Raffin paid in the note numbered 45,425 on 21 November. Raffin was a fruitier who told the investigators that he had changed the note for a William Pierce. He went on to say that at about the same time, he exchanged a further 200 sovereigns for £200 in notes with the Bank of England on behalf of Pierce. James Burgess endorsed the notes numbered 45,421, 45,423 and 45,424. The remaining note was endorsed by publican J Stearn who later endorsed a further £500 of notes. Stearn was questioned and said that he had made the exchange on behalf of Pierce.

Inspector George Hazel, the senior police officer with SER at Folkestone interrogated all those involved in the transportation of the bullion at Folkestone. This included Charles James Chapman who kept one of the keys to the chests in his office and Thomas Ledger, who was responsible for the other. The Inspector also went through the police note books from the previous year and was reminded of an incident a year before the robbery.

In May 1854, Hazel saw William Pierce with another man on the Pier at Folkestone near where the Boulogne ship tied up. Up until 1850, Pierce had been employed by SER as a ticket printer near London Bridge station. One day a letter addressed to Mr Pierce arrived at the superintendent’s office where another William Pierce worked as a clerk. The clerk opened the letter and was surprised to read that it was a request for fraudulent tickets. Hazel, then a police sergeant at London Bridge, was informed and Pierce – the printer – was questioned by him. Pierce was sacked but SER directors decided not to prosecute.

Hazel saw the two men several times and put PC Thomas Sherman to watch them and report back. Hazel described Pierce as in his late thirties originally from Lancashire and retained the accent. He was about 5foot 8inches, thin, fair and imperfectly educated. The other man, was about 5foot 6inches had fairish hair was in his middle to late twenties and could easily pass as a ‘gent’.

PC Thomas Sherman reported that at first the two men arrived at the port and left together and were on friendly terms but after a few days they arrived at different times from different directions and left separately. During that time, neither men spoke to each other. Sherman had noted that the younger man seemed particularly interested in the transportation of bullion to France.

Following Sherman’s report the previous May, Hazel contacted Superintendent James Speer of Folkestone police. He told Hazel that he knew one of the other railway guards, Stephen Jones, who had told him that a man was not only attentive to the departure of boats but also the station booking and masters offices. Jones had given a description of the man and Speer set a plain-clothes police officer to watch. The man’s description fitted that of Pierce. Speer’s police officer reported that the man was staying at Mrs Hooker’s boarding house, 27 Victoria Terrace, Folkestone and had registered using the name Peckham. Another man, who fitted the description of Hazel’s second man, was sharing rooms and had given his name as Archer.

In October 1854, Hazel saw Archer coming out of the Folkestone booking office where Chapman was the clerk on duty. Instead of going on his way, Archer stopped and appeared to be watching what Chapman was doing. When he eventually moved on Hazel asked Chapman what Archer was about and what the clerk was doing after he had left the office. Chapman replied that Archer had been enquiring about a money parcel he was expecting but had not arrived. The job Chapman was doing was making up the money taken that day.

The following day Archer again enquired about the parcel at the Folkestone booking office, which still had not arrived. On third day, it had but Chapman had to sign for it as Archer said that he had hurt his hand, which was bandaged.

The consignment was addressed to C E Archer c/o Mr Ledger or Mr Chapman, Senior Clerks, Folkestone Harbour station. Ledger was on his honeymoon at the time. Hazel again assigned PC Sharman to follow Archer who reported that he had seen him on the Pier with another man, who was not Pecham/Pierce. They appeared to be on friendly terms and left together walking towards the Pavilion Hotel. Hazel had already told Speer of Archer’s return and the latter had organised a tail. The two senior police officers went to the Pavilion Hotel where Archer was with the other man whom Hazel identified as Tester, whom he knew as an employee of SER.

The Arrest for Forgery

Fanny Bolam Kay was working as an attendant in the refreshment room at Tonbridge railway station when senior railway guard James Burgess, introduced her to Henry Agar. She was in her early twenties and was totally besotted by Henry’s worldliness, wit and erudition. Eventually she moved in with him and on 11 June 1853, gave birth to their son Edward Robert Kay – they had not married. Not long after, Henry left for a business trip to United States that turned out to be very successful. On his return, they moved to Harleyford Road, Vauxhall and hired a maid, Charlotte Painter.

William Pierce, who frequently did jobs for Henry, increasingly monopolised Henry’s time and in May 1854, he spent a couple of weeks with Pierce on the south coast. All through that summer and autumn, the two men went off on similar jaunts over which Fanny and Edward were not included. Further, although Fanny was perfectly happy with their home, when Pierce suggested that the family should move, Henry complied without any reference to Fanny. She was angry but reluctantly moved to Cambridge Villas, Shepherd’s Bush, and Charlotte moved with them. The new home consisted of two rooms and a kitchen on the ground floor and three rooms upstairs. There was a separate washhouse in the yard that was accessed through the kitchen.

Still Pierce monopolised Henry and the rows between Fanny and Henry increased. Then, in the middle of May 1855, following another jaunt to the south coast, Henry and Pierce came home one night. They brought with them several leather shoulder bags and dumped them in the kitchen. Pierce told Fanny that if she touched them he would … and then drew his finger across his throat.

The next day Pierce arrived before breakfast and stayed until 17.00hrs. The two men took the bags into the washhouse and spent most of the day in there. They did come into the kitchen at midday for a meal and were hot and dirty. When Henry was out of the room, Pierce sourly told Fanny to keep her nose out of what they were doing. Later Henry, told Fanny that they were ‘making leather aprons.’

Over the next few days the men spent most of the time in the washhouse and when they were not in there, the door was kept locked. Although the windows were whitened so she could not see in, Fanny was aware that they had a charcoal fire going. She could also hear a lot of hammering and knocking, something on which Charlotte had commented.

One day, they left the door unlocked and went out so Fanny told Charlotte to tidy it up and sweep the floor. The young maid was doing this when Pierce returned, saw the girl and that evening, 20 May, Henry told Charlotte her services were no longer needed. Pierce cleared out Charlotte’s old room, except for the bed, and for the next ten days they worked in there keeping the door closed. Fanny looked into the room once and saw a fire in the grate that was brightly lit – the weather at the time was hot. When Henry saw her, he quickly closed the door.

In the evenings, after Pierce had left, Henry would go out coming back late. All of which reduced Fanny to tears. In July, she had enough and leaving the toddler with a neighbour went out, met up with some old friends and had a bit too much to drink. The friends brought her home in a wheelbarrow and Henry was furious. Pierce was there and called Fanny a drunken whore. Henry moved in with Emily Campbell, whom they both knew just coming back during the day with Pierce to work in the spare room.

Emily Campbell had had been living with a man known to Fanny as Humphries and he knew that Henry Agar made his money through forgery. Agar, using the names Archer or Adams, would rent a room, set up an office and advertise for young men as clerks. On engaging one, he would send him to a bank with a forged cheque to exchange for Bank of England notes, with an accomplice following – usually Pierce but sometimes Humphries. If the bank was in anyway suspicious the accomplice would return and inform Agar and between them would clear out the ‘office’ and disappear. This rarely happened and Agar amassed a great number of Bank of England notes. However, as they were numbered and therefore easily traceable, about once a year, Agar went to the US to exchange the ‘hot’ notes for none traceable ones.

In August 1855, a couple of weeks after Agar had moved in with Emily, a young man replied to one of his adverts. Agar employed him and asked to take a cheque for £700 to Messrs Stevenson, Salt & Co. bankers in Lombard Street, for it to be exchanged for cash. The young man did as he was bid and was given a bag of money in exchange for the forged cheque. On this occasion, neither Pierce or Humphries were involved and Agar followed the young man. On realising that the young man had picked up a tail, Agar yelled to him, ‘Sling the stuff over to me and I’ll bolt.’

Agar caught the bag and two police officers, Goddard and Forester, gave chase. Agar was captured and when the bag was opened, it contained 700 farthings. Humphries had tipped off the bank and Scotland Yard was called. Agar was held in Newgate prison and the trial was at the Mansion House, London, in front of the Lord Mayor Sir David Salomons, (1797–1873). Henry Agar stated that was his real name and was found guilty of forgery. He was sentenced to Transportation.

During Agar’s trial, that lasted less than a day, Detective Williams and SER solicitor Mr Rees of the bullion robbery investigative team were joined by Inspector George Hazel and Superintendent James Speer in court. Both the Hazel and Speer identified Agar as Archer. That morning the other two members of the core investigative team, Sergeant Smith and Sergeant Thornton travelled to Dover. There they summoned Witherden to accompany them back to London.

South Eastern Railway track on trestles alongside Shakespeare Beach going to the Town Station. Dover Library

Poor Witherden was in a state of shock as the only information the two policemen gave was that it was to do with the bullion robbery. By the time they arrived at the Mansion House lock up, Witherden was in quite a state and when he saw Agar being led down the steps, his temper blew. He identified Agar as the man who had argued over the bags on Dover station, said that he and his companion had come over on the Ostend boat – which they had not – and then given him a tip on the night of the robbery!

Agar denied any knowledge of Witherden’s accusation and was moved to Portsea to await Transportation. However, at the request of Scotland Yard, he was held at Portsea while they continued their investigations.

- Presented:

- 11 May 2014