With the end of Napoleonic Wars in 1815, spending on defence in Britain was dramatically reduced although on Western Heights the Shaft Barracks and the Drop Redoubt continued to be manned. In Quebec the situation was very different, between 1820 and 1832, the Citadelle, the fortress that can be seen today, was constructed. This includes structures that the French had built such as the Cap-aux-Diamants redoubt (1693) and a section of the French enceinte (enclosure) of 1745. The new fortification was less dependent on the bastion; instead, heavily armed, multi-tiered towers were built enclosed by ditches. These were defended from covered structures, ‘caponnieres’ that projected into the ditches creating sheltered flanking positions for defending troops.

Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, the 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava was appointed Governor of Canada 1872-1878 and he ensured that the fortress was preserved. Of note, the Marquess was appointed the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports from 1891 to 1894 and the installation took place by the Bredenstone, close to the Drop Redoubt, on 22 June 1892. That was the last time the ceremony was held on the historic site.

The perceived threat of Napoleon III led to the setting up of a Royal Commission on 20 August 1859 to look into the Defence of the United Kingdom. Major William Francis Drummond Jervois (1821-1897), whose advice eventually led to the building of the Admiralty Pier Gun Turret – was Secretary. Dover was chosen as the primary point for what turned out to be the most extensive and expensive programme of defence construction up to that time.

Extensive works were carried out on Western Heights between October 1859 and February 1862, costing £37,577, and included a ditch and lines connecting the Citadel to the Drop Redoubt. At the Redoubt, four caponnieres were erected in the ditches so that guns could be mounted to fire along the floors and bombproof barracks for officers. A report noted that there were positions for 17 guns on the terreplein (the level surface on which heavy guns are mounted) and 15 in the caponnieres. Other changes that took place at this time ensured that as much heavily artillery could be used on the enemy at the earliest opportunity.

The works also included the introduction of the noonday gun that was first fired on 2 June 1859 and continued until 1912, when the lack of time accuracy called for it to be stopped much to the displeasure of the towns folk! The works in the Drop Redoubt for a while exposed the foundations of the western Roman Pharos – the Bredenstone.

Lord Palmerston (1784–1865), the then Prime Minister, was installed as the new Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports on 29 August 1860. The event took place around the newly exposed Bredenstone. It was reported that a grand procession, in their full regalia, ‘was marshalled and toiled up the hills to the conspicuous height from which the noon gun was fired, and the ceremony of the inauguration having been performed.’ Afterwards, work continued on the Western Heights defences, and by the end of the 1860s, it had evolved into a large and impressive fortress.

Western Heights remained a major fortification with continuing modernisation throughout the remainder of the century. Effective breech-loading guns were introduced, along with electric searchlights, telephone, telegraph communications, and along with fire fighting equipment, used to supplement equipment at the Castle and in the town.

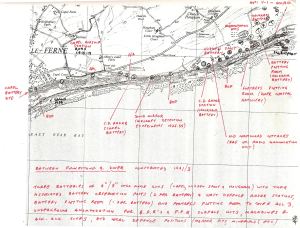

As a new threat was perceived from the German warship construction, from the mid-1890s the defensive batteries close to the harbour were augmented by alterations to existing higher batteries, such as St Martin’s Battery on the Heights. There, high-angle and longer-range mountings were provided for guns and two powerful long-range batteries, 3-miles, apart were built on either side of Dover. Langdon Battery on the east side of Dover Castle and the second, just beyond the extremity of the Western Outwork. In 1900, a new war signal station came into operation at the Citadel and from 1911, the number men accommodated at the Heights, as the country prepared for War, increased dramatically.

With the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918), Western Heights was primarily used for accommodation. Albeit, the existing defences were strengthened and supplemented with a ring of field redoubts on the hills around Dover. In 1916, these were replaced with lines of entrenchments. The first aerial bomb on the United Kingdom was on 24 December 1914 that landed in a garden that backed on to Taswell Street, near where the Dover Society Plaque is today. This led to new enforcements being set up to guard against air attacks such as anti-aircraft guns and searchlights.

As heavy fighting on the Continent increased, South Front Barracks, on the Heights became a rest camp for soldiers on leave from France. The number of men staying there between Christmas 1917 and the end of March 1918 became a cause of concern, but the great German offensive soon emptied the barracks as the men went back to the Front.

Although the war to end all wars was over, the military presence stayed on Western Height until 1929, when it was reduced. During the War concrete-slab sound mirrors were built along the cliffs to the west of Western Heights as well as at Fan Bay, to the east of Dover. More were added in the 1920s and the sound mirror at Abbot’s Cliff can still be seen. However, in the 1930s, it was generally agreed that peace was to stay and calls for the demolition of military emplacements became vocal. In 1936, the South Lines Battery was converted into a promenade.

Following the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), the number of military personnel increased significantly, defences were strengthened and anti-aircraft gun batteries were built equipped with radar for target-detection and gun-laying. In early 1940 the first Heavy ack-ack regiment created five sites across the Dover area with 3-inch open-sight guns. The sites were numbered D1 to D5 and DI was located on Western Heights above Farthingloe Farm, close to the Citadel Battery – remnants of which can still be seen. The others were located east of Langdon Battery, at Frith Farm near the Duke of York’s Military School, north of St Radegund’s Abbey and Marine Parade. The latter was found to be unsuitable but the remaining four, in 1944, were were part of the ‘trip line’ batteries along the Kent coast that countered VI flying bombs.

Western Heights role in providing barrack accommodation again became its primary function. The defences were, like elsewhere, strengthened. In St Martin’s Battery three 6-inch breech loading gun were installed, the old gun pits were filled with concrete, and concrete brick gun houses were built over the top. Two Type 23 pillboxes were also constructed nearby. At the Citadel Battery, two 9.2-inch guns were mounted and two Type 24 pillboxes were constructed. Types 23 and 24 pillboxes were built around the perimeter along with weapons pits, slit trenches and blast shelters.

When peace returned the government decided to run the military establishment on Western Heights down and in 1949 the War Department said that it was willing to lease the land for 99 years but not to sell the freehold. Three years later, it was announced that the Citadel was to be converted into a male prison for 300 inmates. The building was taken over by the Home Office in 1954 for use as a prison but four years later the Prison Commissioners relinquished it to HM Borstal Institution. Eventually, the site became a Young Offenders Institute, during which time houses for officers were built on the area where once the village of Braddon stood.

The War Office ordered the demolition of most of the South Lines Casemates and the adjoining caponniere in 1959. The following year the Department wrote to Dover Corporation giving details of land surplus to military requirements on the Heights. David Bevan, the Borough Engineer, stated that approximately nine acres in the vicinity of Grand Shaft Barracks could be considered for industrial purposes. The council authorised the Town Clerk, James A Johnson, to open the negotiations and eventually 23.5 acres of land were acquired by the council. That same year the demolition of South Front Barracks began in earnest.

The War Department transferred 81 acres to the Prison Commissioners in 1962, for the Borstal Institute. Land was also leased to Dover Corporation, including 15 acres adjoining what had been the Grand Shaft Barracks. This the council designated for residential purposes. The former South Front Barracks site (16.5 acres) was designated for industrial use and 118 acres, mainly consisting of the north facing, steeply sloping, hillside was to remain undisturbed. However, it was agreed that a further 1.5 acres of moats, that had been acquired, were to be filled in using the town’s domestic rubbish.

1962, also saw the demolition of the Garrison Church, built in 1859, and adjacent Victorian housing. The bell and the ornate cross were given a new home at Old Park Barracks. Shortly afterwards the massive gate with drawbridge on the South Front Road, which used to control the entrance to the Western Heights from the Ropewalk was demolished. These were carried out by the Dover Erection and Demolition Company, owned by John Ullman, and authorised by the Prison Commissioners. That year Avo’s opened their factory on land designated for industrial purposes.

Authorisation was given for Dover Corporation to purchase all the military land on the Western Heights in 1963, with the exception of the Borstal Institution. Comprising of approximately 126 acres, the land, to quote a report at the time, extended from the ‘rear of Clarendon Road, Westbury Crescent and Mount Road, over the top of the hill, encircling the Citadel, and down the other side to the rear of the Corporation’s Ropewalk and Aycliffe estates, along to the Grand Shaft Barracks and down as far as Cowgate Cemetery.’ The council purchased the land for £20,250.

Of this, 96 acres was expected to be unsuitable for any development. The 11-acre Grand Shaft Barracks and land behind Westbury Crescent were earmarked for residential purposes and the remainder, approximately 17 acres, for industrial purposes. This included the site of the South Front Barracks that was not already occupied by Avo’s, the former Royal Engineers Headquarters and the Military Hospital on the right of Channel View Road.

Although the Commissioners for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments were interested in proposals for all of these sites, Dover’s elite, generally felt that there was very little of historic significance in the area, only citing the buried western Pharos – Bredenstone – and the demolished Garrison Church. Instead, emphasis was given to dealing with the town’s rubbish problems. The lease, for 21-years, the South Front Barracks site to Corrall’s as a coal-stacking yard was agreed in 1963, subject to a number of covenants to guard against dust. The rent for the first seven years was £360 increasing to £560 for the last seven. Surface works were to be carried out by the company at an estimated cost of £8000.

James A Johnson, Dover Town Clerk 1944-1968 saw the designation of the Western Heights as an Ancient Monument as a ‘piece of nonsense’

The Corporation gave permission for the demolition of the Grand Shaft Barracks in 1965 at a cost of £3,100. However, the Ancient Monuments Commission designated the foundations of the Knights Templar church, the site of the remains of the Bredenstone and part of the moats of historic interest. The latter blocked the Corporation intention of using the moats for the town’s rubbish. In their objection, the Corporation stated that it was necessary to fill in the moats to enable a major road to be built across the Heights.

In 1966, Avo’s increased their floor space and Racole Trading and Manufacturing Company Ltd won an Industrial Development Certificate from the Board of Trade to build a factory nearby. This followed representations by Dover’s MP, David Ennals. However, the following year, much to the Council’s disapproval, the Ministry of Public Building and Works stated that even more of the military features on the Heights were to be preserved. These included the Grand Shaft, Drop Redoubt and the moats. In order to placate the council, the Ministry agreed to contribute £12,000 towards the cost of a new access road to the Heights from Military Road.

By February 1968, Dover Corporation had raised £17,250 from the sale of land on the Heights. A year later the council were favourably considering two development proposals, on what they classed as ‘one of the best development sites in the town,’ – where the Grand Shaft Barracks had once stood. Consideration was given to flats and a possible hotel. In 1971, the council made application to Kent County Council (KCC) for the construction of an estate of good class houses and flats on the site. If consent was granted, it was expected that the land would be sold to an interested development company.

Led by Customs Officer Doug Crellin, volunteers that included the author, worked hard to clear the Grand Shaft of dumped cars, defunct twin-tub washing machines and abandoned fridges and then restore it. During that time, Doug died and in April 1980, a special ceremony was held when a plaque was unveiled by his widow, at the top of the Grand Shaft. Doug was a member of the New Dover Group, which later became the Dover Society, and the Chairman of both, Jack Woolford, gave the address.

Townsend Thorensen moved into their purpose built offices in Channel View Road in 1983. Named Enterprise House the 7,500 square metre office block was designed blend in with the shape of Western Heights. Within the next few years, under the auspices of English Heritage, we volunteers and Junior Leaders from Old Park Barracks cleared the Drop Redoubt of dumped vehicles, machines and general rubbish. In 1986, it was opened to the public for the first time.

However at the Dover District Council (DDC) Land Committee meeting of 9 November 1988, it was resolved, ‘That subject to the outcome of the A20 Inquiry land at Western Heights, Dover now identified, be offered for sale by tender for residential or other appropriate purposes.’ In August 1989, DDC announced that they were putting 10.5acres on the market and the council produced a Developers Guide. Organised by Jack Philips, some 4,300 locals signed a petition against the proposal but the council took little notice.

At the time, this author was teaching at the University of Kent and a colleague pointed out that she could object to the proposal at the Planning Inquiry into the Local Plan that was going through the process at the time. She put the case together that was accepted for a Hearing, much to the annoyance of Councillors and Officers of DDC. Much of Part I and the above comes from the submission to the Inquiry.

The Hearing lasted one day and the author was supported by husband Alan and one witness, Jack Phillips. The fight was gruelling and although the media were not in attendance, it was expected that we would lose at great expense to the ratepayers of Dover. However, the Planning Inspector upheld our objections, writing, ‘Even if I could be persuaded that some developer could produce an exceptional scheme that would be suitable for the site I would still take the view that the allocation should not be made. I say that because once an allocation is made there is a limit to what a local planning authority can do to maintain special standards.’ Neither the 1996 nor the 2002 Local Plans approved of similar developments on the Western Heights and this was reflected in the current Local Development Framework.

Following the results of the Inquiry and with the help and perseverance of the then DDC’s Director of Planning, John Clayton and the White Cliffs Countryside Project (WCCP), much was achieved during the following years. The clearing rubbish and scrub, introduction of Dexter Cattle to keep the scrub down, the ‘Soldiers Life’ trail, the north bastion steps, wooden gates etc. In 1994, IMPACT – The Joint Environmental Initiative of KCC and DDC – started work on the faithful reconstruction of the Grand Shaft that we see today.

In 1999 Dover’s former Chief Executive, John Moir, was quoted as saying that the council were working with English Partnerships on a new imaginative scheme for the Western Heights. This resulted in the setting up of the Western Heights Preservation Society (WHPS) by English Heritage in 2000. The Society is made up of enthusiastic volunteers but financial resources have been scarce.

Shortly after, the Dover’s Young Offenders’ Institute in the Citadel closed and refurbished as a detention centre for asylum seekers. During the previous years, the officers’ houses were sold and bought by their occupants. Led by Richard Pimblett, these residents applied for, and successfully gained, village status for the estate. Taking the ancient name of Braddon at midnight on 20 October 2001 – the full story and that of Farthingloe can be read in the author’s book, Haunted Dover.

In July 2003 the Victoria Hall, erected in 1898 by the Church of England Soldiers and Sailors Institute as a temperance alternative to existing recreational facilities, was razed to the ground. It was a long single storey building with a dedication stone, laid by Lord Roberts of Kandahar VC, on 8th December 1898. Following the addition of a two-storey wing, it was converted into an infant’s school and Men’s Education Room in 1903. In 1922, a large Dining Room was added and in the 1950s, the Hall became the Young Offenders’ Institution Officers’ Recreation Club. Following the fire, what was left of the building was left to rot.

English Heritage, in 2010, announced that they planned to use prison inmates on day release to clean up Western Heights. This, they said, was to be undertaken in an effort to get the 18th-19th century fortifications off the Heritage at Risk register. Although Western Heights was protected from development, China Gateway International (CGI) were seeking planning permission for a housing and hotel development on the Heights, together with a massive housing development along the ancient Arthurian valley of Farthingloe. The latter is within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and of equally important tourism potential to Dover.

The proposal was outside DDC’s Core Strategy, adopted in 2010 and neither of the sites was listed in the supporting Strategic Housing Land Allocations Assessment. Because Western Heights and Farthingloe are some distant apart, traditionally, they have been treated as separate entities. However, it was apparent that they were combined so that Western Heights – with the desperate need for finance – was the proverbial ‘sprat to catch a mackerel’, for the urbanisation and profit potential of the virgin Farthingloe valley.

The ‘sprat’ used by CGI, and endorsed by those who were happy for the urbanisation to be at last realised, rested on Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. This allows developers to enter into a legally binding agreement to provide funds in return for granting of planning permission – usually for Executive style housing – without the 30% Affordable housing that is normally required. In this case, under Section 106, CGI have said that they will give £1million with a further £5million later but this appears to be dependent on profits.

Lara Pimblett, the daughter of the late Richard Pimblett, led the main campaign against the development and hundreds of objections were lodged. English Heritage made it clear that they had grave doubts about the wisdom of the proposed development and the Council for the Protection for Rural England (CPRE) were at the forefront of the national organisations objecting.

Nonetheless, planning permission was given for the developments on both Western Heights and in the Farthingloe Valley. This is for 521 residential units, 90-apartment retirement block, 130-bed hotel and 150-person conference centre, a health facility, conversion of a thatched barn to pub/restaurant and the conversion of stable block to retail shop and the conversion of the Drop Redoubt to a visitor centre. It is expected that the project will take seven years to complete.

This contrasts with Quebec, where the Citadelle is a National Historic Site of Canada and is located within a World Heritage Site a designation given in 1985.

- Presented: 23 August 2013