One of the Dover Society trips some years back, was to Chartwell, Westerham, the home of Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1985), from 1924 to his death, and the nearby Quebec House. The latter was the home Sir General James Wolfe (1727-1759) during his childhood and the National Trust now owns the house. My interest in the latter, General James Wolfe, stemmed from when I was preparing the case against a proposed development on Western Heights back in the late 1980s / early 1990s.

The case was heard at a Local Plan Inquiry where, with the help of Jack Phillips and Alan, my husband, we were successful in stopping the development going ahead. A further outcome, we hoped, would be the recognition that the Heights was an Ancient Monument, and placed under the auspices of English Heritage in conjunction with Dover District Council (DDC). Therefore, we hoped the area would no longer be starved of finance in order to make it ripe for developers to move in. Sadly, the site is still starved of money, nonetheless, the story of Western Heights is well worth telling.

Dover is a narrow valley opening up to the sea between two high cliffs, Dover Castle dominates the Eastern Heights and on the opposite side of the valley are the Western Heights. The main thrust of my case was the historic fortifications and I drew parallels with those in Quebec, Canada. The latter are located within a World Heritage Site a designation given in 1985. In English history, James Wolfe is synonymous with Quebec and I had every reason to believe that the General was in Dover prior to the Quebec campaign. The trip to Westerham confirmed this.

General Wolfe was born at the vicarage in Westerham, the elder of two sons of Lieutenant-General Edward Wolfe (1685–1759) and his wife, Henrietta (d. 1764). Shortly afterwards they family moved along the road to what is now called Quebec House and in 1738, the family moved again, this time to Greenwich. In 1731, James was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant in his father’s regiment and followed a military career. On 27 June 1743, he distinguished himself at the Battle of Dettingen (1743) on the River Main, Germany, during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). In January 1749, he was appointed Major in the 20th Foot and began compiling his ‘Instructions for Young Officers,’ published in 1768.

The instructions were initially prepared in the event of a French Invasion. At the time, the British Army used a technique known as platoon firing, whereby the infantry battalion was subdivided into small platoons who would fire in sequence thus maintaining constant firing and throughout the musket was held at shoulder height. Wolfe introduced the much simpler technique of levelling the bayonet with the hip and creating an offensive rather than defensive weapon. These and other techniques were later incorporated into the official regulations and were the basis of British Infantry tactics in the American War of Independence (1776-1783) and the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815).

Around 1753-1754, Wolfe was stationed at Dover Castle and was involved in discussions that were taking place in order to convert it into an artillery fortress. Over the following two years extensive alterations took place at the Castle including:

– The defence of the landward approaches from the north and east;

– Lowering the towers between Fitzwilliam Gate and Avranches Tower to give the artillery a field of fire;

– A new Mote Bulwark had been built in the 1730s and included a semi-circular Battery that had places for eight guns. This was enlarged.

In May 1756, Britain declared War on France – the start of the Seven Years War (1756-1763) and on 6 September 1857, Wolfe sailed with an expedition to Rochefort on the Atlantic coast of France. The French town had been designed as the ‘refuge, defence and supply’ for the French navy and its harbour had been fortified under the instructions of the Marquis de Vauban (1633–1707).

The landing was successful on the nearby Île d’Aix where the ramparts were destroyed. However, the raid on Rochefort was failure due to a combination of Vauban’s defences and indecision in the British command. Afterwards Wolfe wrote a detailed account and was reported as saying, ‘I am not sorry that I went, notwithstanding what has happened; one may always pick up something useful from amongst the most fatal errors’ (5 Nov 1757, The life and letters of James Wolfe, ed. H. B. Willson, 1909). Wolfe’s observations were to put him in good stead against the French at Quebec in 1759 and help to formulate the plan for Dover’s Western Heights.

French explorer, Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) stayed in the area that became Quebec in 1535 returning in 1541. His intention was to build a settlement but the harsh winters and hostility from the indigenous population led to the idea being abandoned. However, in 1608 Samuel de Champlain (1574-1635) founded what became Quebec City within a stronghold with defences designed by Vauban. The city was situated on a high promontory formed on one side by the St Lawrence River and on the other by the much smaller St Charles River.

On 23 January 1758, Wolfe was appointed one of three brigadier-generals in North America serving under Major-General Jeffrey Amherst (1717–1797). They were to lead an expeditionary force to capture the fortress of Louisburg on Cape Breton Island. Wolfe distinguished himself and the army besieged Louisburg. He then returned to England without authorisation and managed to persuade the Prime Minister (1756-1761 & 1766-1768), William Pitt the 1st Earl of Chatham (1708-1778), to lead an expedition to take Quebec. Wolfe was promoted to Major-General, given the authority he needed and put together a force led by officers he knew would serve him well. They sailed for Canada on 14 February 1759.

Wolfe was 4 miles downstream from Quebec by 27 June 1759 with every intention of making an attack. What happened next is well covered in the history books; suffice to say things did not go well for Wolfe and his troops. During the following weeks Wolfe spent his time looking for weaknesses in the French defences and a second attempt was made in the early hours of 13 September. By dawn his army had scaled the cliffs, where the defences were weakest, to the Plains of Abraham. The French made a counter attack but were routed. Wolfe, was fatally wounded and his body was brought back to England where it was interred in the church of St Alfege, Greenwich, on 20 November 1759. Quebec surrendered five days after Wolfe had been killed and eventually the whole of Canada came under British rule.

The notes that Wolfe made on the French defence weaknesses were brought back to England, and among those who studied them was Captain Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821). In the 1870s, Captain Page was stationed in Dover and later built 110 London Road, Buckland – which still stands – with his wife Albinia formerly Woodward (b1760) of Dover. Both Captain Page and his wife played an active part in the town’s activities and the continual threats from France, was instrumental in setting up the Dover Volunteer Association. They were trained to operate the town’s gun batteries. His other lasting legacy was the beginning of the fortifications on Western Heights based on Wolfe’s observations in Canada.

When the American War of Independence (1776-1783) broke out, France supported the colonials and Britain, fearing an invasion, strengthened the national defences. Captain Hyde Page was put in charge of Dover’s defences and due to the close proximity to France and in the light of Wolfe’s exploitation in the weaknesses of the Quebec defence system, Page, organised the building of fortified batteries along the seafront, for which he was knighted. These were Guilford Battery, under the Castle cliffs; North’s Battery, where Granville Gardens are today; Amherst Battery to the east of where the Clock Tower at present stands; and Townsend Battery close to the present day Lord Warden House.

Between AD 115–200, the Romans built a large fort, the Classis Britannica at the base of north-eastern slope of the Heights. They also built two massive lighthouses, or Pharos, one of the Heights and the other on the eastern cliffs. The latter still stands, close to St Mary-in-Castro Church, within the Castle. Close to the Classis Britannica fort was a large civilian settlement with many substantial buildings. One of these was the ‘Roman Painted House’ (circa c. AD 200), so called because of the painted wall plaster used in its fine decoration – this can still be seen today. From about AD270 Roman Britain came under increasing attack from Saxon pirates and it became necessary to fortify the shores. Large, strong Roman Shore Forts were built, including one at Dover but eventually the Romans abandoned Britain.

By the twelfth century the round church, or chapel, long time attributed to the Knights Templars, was built on Western Heights – the foundations can still be seen. Nearby, was the medieval village of Braddon. Following the Restoration (1660), the installation of the Lord Warden took place near what remained of the old Roman Pharos, at the time called the Breden Stone – later Bredenstone. The area was, at the time, called the Devil’s Drop, as it was from here that felons were hurled off the Heights to their deaths. The Lord Warden Installation ceremony continued to take place on the Heights until 1891.

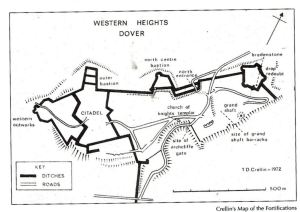

The Board of Ordnance, in 1781, bought two parcels of land on the Heights, totalling 33 acres and when peace returned Captain Page was given the job of creating a redoubt, of the type that Wolfe had advocated but with modernising modifications. The works on Western Height, designed by Page, incorporated a self-contained redoubt fort at the eastern end of the hill and a Citadel on the west, with entrenchment’s between. It was the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) that led to the building of the large fortress on the Western Heights. For this and based on the works of Wolfe and Page, Captain William Ford drew up plans with the intention of housing a garrison of sufficient size to secure the Heights against attack from the west or the rear. At the same time, enabling to direct flanking fire onto any invasion force attempting to assault the town and port.

Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Twiss (1745-1827), the building of the defences on Western Heights began in April 1804. Followed Page’s fieldwork’s, strong defensive lines linked the Citadel – the main defence – with the redoubt on the eastern side. The Citadel was strengthened; the Drop Redoubt and the North Centre Bastion along with bombproof barracks and connecting lines were constructed. He had previously designed the Guilford Shaft, on the eastern side of the valley, to link the Mote Bulwark with the Castle. Within this structure Twiss designed Casemate Barracks were begun in 1793 to provide accommodation for soldiers. Initially they were four parallel tunnels extending approximately 100-feet into the cliff with vertical ventilation shafts and reached by a terrace that extended from just above Canons Gate. Along what are now Townwall Street and Woolcomber Street a defensive canal was dug – all traces of which have now gone.

At St Margaret’s Bay, a wall that formed part of the defences can still be seen. This and similar outlying defences were built at the instigation of Sir Henry Popham, from East Kent, and Sir Charles Gray then commandant the South East Kent Forces. The defence of the coast was manned, for the most part, by the Cinque Ports Volunteers.

For the troops at Western Heights a link between the barracks with the port to enable rapid troop movement was built. The monumental Grand Shaft was designed by Page, was constructed between 1805 and 1807. It consists of three spiral staircases around a vertical circular brick shaft that descends for 140 steps to a tunnel linking up with Snargate Street. The Barracks, named after their proximity to the Grand Shaft, was erected and could accommodate 1,300 men, 59 officers and eight horses. Nearby was a 180 bed military hospital was completed in 1804.

All of these works were carried out under the auspices of William Pitt the younger (1759-1806), Prime Minister (1804-1806) – the then Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1792-1805) and the Secretary of State for War (1802-1806), Sir William Dundas (1762-1805). When finished the Western Heights fortifications could accommodate 5,000-6,000 men and cost approximately £240,000. On 11 May 1807, some three years after the military works began on Western Heights, a special court was convened to ascertain the amount of compensation that the former Western Heights land owners should receive.

The Hearing was held at the Ship Tavern on Strond Street, besides what later was renamed Granville Dock. In the Chair were General Sir Thomas Trigg (circa1742- 1814) and General Twissly Moore with the jury drawn from Dover freeholders. These were Samuel Latham (1752-1834) – foreman, Robert Hunt (b1754), Charles Stone, William King (b1747), John Thomas Neates, Thomas Chester (1752-1823), William Cullen, George Harman (d1841), William Collins (b1740), Samuel Collett, Richard Marsh (1751-1840), and Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819).

The Council for the Crown was a Mr Garrow who started proceedings by looking at the lands that had belonged to Thomas Papillon of Acrise. He called Mr Wyatt, Surveyor for the Government and also George Leith (1756-1832) and Mr Baldock, both of whom had surveyed and valued the land at the request of Thomas Biggs of the Ordnance Office. Papillon’s land amounted to 41 acres on the Heights plus 10½acres at the nearby Archcliffe Fort for which he demanded £8,000 compensation.

The jury estimated that the 41 acres were worth £60 an acre, which amounted to £2,460, while the land taken by Archcliffe Fort was worth £4,100. This came to £6,560 so they rounded the compensation down to £6,000guineas equalling £6,300. The next case appertained to William Coleman of Dover for damage and loss sustained by him at different times since the works have been carried on lands, which he had held as a tenant of Papillon. The jury decided that Papillon should compensate Coleman out of the £6,300.

About six acres of land opposite Archcliffe Fort that belonged to John Monins’ heirs, was the next case. At the time the War Office commandeered it, George Stringer (1767-1839) of Castle Hill House held the land. He had rented this out to the town’s butchers for their livestock and they had paid Stringer £16 a year out of which he gave the Monins estate an agreed percentage. The jury estimated that the land was worth about £333 per acre and decided in total that the compensation would be £2,000 for the six acres. It was left to the different parties as to how this would be divided. Robert Walker (1767-1834) did equally as well, asking for and receiving £40 for posts and rails and other damages and expenses he had sustained.

Military Hill – building started to take place after the 1860 ruling as can be seen in this c1900 view from Priory Place. Dover Library

James Gunman (1747-1824) made what turned out to be the longest lasting and the most controversial claim for £600 as compensation for agricultural land taken from him. This was to create the Military Road from above York Street to part way up Military Hill. This, Gunman argued, had also reduced the value of his land on either side of the new road but the jury decided that this land would increase in value as it had effectively been turned into building land. They therefore awarded Gunman £100 and, as they predicted, Gunman sold the land on either side of the Military Road for building purposes.

The Town Council with the intention of building a small housing estate bought this land, but the War Office barred none Military personnel using Military Road. The Council protested but when the Government’s Privy Council assessed the situation they supported the War Office giving them permission to close the road for 12months. When the time was up, the Council again asked to use the road for access to their land but again the Privy Council sided with the War Office and it was closed for a further 12months. This annual situation went on for nearly 50years and on each occasion the Dover Council had to pay the costs of both parties. To make matters worse, as they owned the land on either side of Military Road, they had to pay for the upkeep of the verges/pathways.

In the meantime, on what was the Council owned land the local military had encouraged the development of a ‘red light’ slum to serve the ‘needs’ of the garrison. The residents of this ‘red light’ district did not pay rates either to the military or to the Council. About 1855, instead of the annual legal contest with the War Office by Dover Council, the War Office authorised the building of terraces on the Council owned land! The infrastructure was laid and Mount Pleasant, Bowling Green Hill, Durham Hill, Union Row and Blucher Street were built. When the properties were fully occupied the War Office submitted a bill to the Council for the annual rent of the land on which the properties were built!

Dover Council refused to pay so in response, the War Office authorised the estate’s newly laid roads with water and sewerage pipes underneath, to be smashed using heavy gun carriages. Although the Council protested and tried to show them the evidence that they actually owned the land, the War Office took no notice. The War Office again demanded the ground rent and threatened to smash Dover’s infrastructure nearer the town centre and at the same time, openly encouraged the red light district personnel to use the residents gardens as lavatories.

In 1860, local solicitor, Edward Knocker (1804-1884) was appointed the Town Clerk and his first job was to try and reach a compromise with the War Office. On examining the evidence, Knocker realised that in fact the disputed area did belong to the Council and he also worked out a way of dealing with the red light district. The council agreed to allow Knocker to pursue the case as he saw fit. Using the Public Health Act of 1848 and with authorisation from the General Board of Health, Knocker ordered the relaying of the water mains and sewerage drains. Then, under the auspices of the Town’s new Surveyor, John Harvey (d 1879) from Gloucestershire, the pipes were covered with a sufficiently strong road surface to take the weight of the heavy gun carriages. When completed, Knocker then sent the bill to the War Office with notice that he would take legal action if they did not pay up.

At first the War Office tried to call Knockers bluff but he issued a writ which the War Office asked him to withdraw, saying that they would send the money. Knocker did as they asked but instead the War Office did exactly what Knocker expected them to do, they started legal proceedings against the Council! They argued that the land on which the estate was built was on land owned by the military for which the Council owed them the ground rent. Further, the Council had no right to lay the water and sewerage pipes on what was military land.

Knocker responded, saying that the Council had built the houses on land that the deeds confirmed belonged to them and that they had undertaken their obligatory duties demanded by the Public Health Act and approved by the General Board of Health. Further, the War Office had made no attempt to provide any services, as prescribed under the Public Health Act, to the shanty town that had developed on their land and had encroached on Council owned land over the previous 50years. The Court’s judgement was that the War Office were obliged to accept the Laws of the Nation and the Public Health Act prevailed over the views of the War Office. They added, that in their opinion, the deeds proved that the Council owned the disputed land.

The War Office were furious over the decision and initially sought to appeal but possibly on legal advice withdrew their claim. Instead they closed the bottom of Military Road with a gate manned by armed guards. Although this blocked vehicle access to the small estate as well as over the Heights to those without military authority, locals quickly found ways around this. Further, as the roadblock seriously limited access to the red light district it started to empty and under the Public Health Act, Knocker had the area cleared. Although the roadblock eventually disappeared the council’s Mount Pleasant estate, as it was called, by the early twentieth century had become a slum.

Using the Housing Act 1930, Dover Corporation considered the housing needs of Dover for the following five years and this included the clearance of Dover’s slums. One of the areas earmarked was this estate however World War II (1939-1945) intervened and during that time the area succumbed to significant amount of shelling. Following the War the area was cleared and was replaced by the Durham Hill flats we see today. About the same time the lower part of Military Road was formally dedicated for public use over 150 years after it had been purchased by Dover Council!

Part II of the Western Heights focuses on its military history.

- First Presented: 23 August 2013, Expanded 20 May 2018