Dover Harbour Commission the predecessors to the Dover Harbour Board (DHB), was set up by Charter in 1606. At the time, Dover’s harbour was at the west end of the bay and consisted of the Great Paradise and the Great Pent. The latter eventually became the Wellington Dock. The Great Paradise was the outer harbour and its entrance was frequently choked with shingle caused by the Eastward Drift.

The Eastward Drift is a natural phenomenon that brings shingle from the west and before the building of the Admiralty harbour, deposited it at the eastern end of the bay and on the east side of any obstruction built out into the bay. This included the then harbour entrance – now approximately where the north and south pier heads are. The Eastward drift problem was particularly bad at neap tides, as the tidal flow was too weak to wash the pebbles out of the harbour. In order to try to combat the problem the waters of the River Dour were collected in the Great Pent, which was dammed at the Great Paradise end (now Wellington dock) so that it acted as a reservoir. At neap tides, the reservoir was released through great sluices to wash away the shingle that had collected in the harbour entrance.

The first harbour to be created at the western side of the bay was given the name of Paradise Pent by the mariners. This had silted up by end of the 16th century and a new larger outer harbour was created and called the Great Paradise. In 1579 Elizabeth I (1558-1603) granted Dover the right of ‘Passing Tolls’ – a tax to pay for harbour works and initially 3d (1.25p) per ton, was paid by all ships passing through the Strait of Dover, whether they stopped at Dover or not. The Passing Tolls Acts were renewed many times over the next 400 years and the money was used for harbour repairs.

By the time Charles II (1649-1685) landed on Dover beach at the Restoration in 1660, the Great Paradise was becoming marshland covered by seawater at high tides. Thus, the King’s ship was forced to anchor in the bay and he had to be rowed ashore! The original Paradise harbour had long since become a marsh and was, by this time, drying out. On this reclaimed land, the Pier district was already growing. Indeed, the 1606 Charter gave the ground rent gained from reclaimed land to the Harbour Commissioners and this still holds.

On the reclaimed land along the north side of the Great Paradise, the rich merchants of the town built their homes and warehouses and laid down quays with the houses fronting onto Strond Street. In 1670, the Harbour Commission exerted their rights to create one continuous quay on which was built the Custom House. At the time, the Custom House was near Bench Street but that was falling into disrepair and demolished in 1682.

The problem of the Eastward Drift remained such that towards the end of the 17th century the town was so poor that the council had to sell some of its precious artefacts – three silver maces. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William III (1689-1694) ordered Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovel (1650-1707) and Captain Whitham to make a survey of the state of Dover harbour and give recommendations. They advocated that the Harbour Commission spent some of their revenue on harbour repairs, so nothing happened!

Queen Anne, before 1713 by Godfrey Kneller(1646-1723) , she ensured that recommendations for clearing the harbour of silt were instituted. Dover Museum

In 1699, Mayor Edward Wivell successfully petitioned the King for the renewal of the Passing Tolls Act for harbour repairs but it was not spent fruitfully. When Queen Anne (1702-1714) ascended the throne, Mayor John Hollingbery, petitioned her and she listened. The recommendations of 1689 were to be carried out and the first Crosswall was built across the Great Paradise.

The Crosswall went from Union Street, then called Snargate over Sluice, to the Pier district and was built of wood. The wall created an inner harbour called the Bason and the main outer, Tidal harbour. Gates were fitted into the Crosswall opposite the mouth of the Tidal harbour and during neap tides, the gates would be opened in the hope that the whoosh of water would wash away the shingle bar. It was not very effective then or for the next hundred years.

As the population of the Pier district grew so did the popularity of using the wooden Crosswall as a short cut. Even in dry weather, it was dangerous, especially when it was crowded, but on wet days, it was treacherously slippery. Between 1727-1732, it was faced with stone but the relatively narrow lock gates still proved dangerous. In 1738, a swing bridge was erected over the entrance to the Bason and shortly after stalls appeared. At the west end of the Crosswall a bustling, thriving fish market grew.

Between 1819 and 1821, the Crosswall was reconstructed by the then harbour master, engineer James Moon, and given new gates and sluices. The operating mechanism for the new sluices was more cumbersome than before so it was decided to build an edifice to house them and to turn this into a feature. The final building was a clock tower, with four faces that, with great ceremony, was opened on 14 April 1830. Because of the lack of symmetry, a second tower was built and this had four compass faces and James Walker using plans by Thomas Telford made improvements to the sluices in 1834.

In 1847, work started on the Admiralty Pier and it was hoped, amongst other things, that this would deflect the Eastward Drift away from the harbour entrance, it did not. The London, Chatham and Dover Railway opened in 1861 with the Harbour Station flanking the Tidal Basin adjacent to Custom House Quay. To accommodate the new line properties were demolished and the Crosswall was reduced in length at the west end forcing the fish market to move further east along the Wall.

When the Harbour Commission was reconstituted to a Harbour Board (DHB) in 1861, the Passing Tolls Acts were abolished. At the time Steriker Finnis (1818-1889) was chosen as one of Dover Town Council’s representatives on the Board and on the death of Captain Jeffrey Wheelock Noble RN (1805-1865) in March 1865, Finnis succeeded him as the representative of the Admiralty. Finnis was voted deputy Chairman a position he held for almost a quarter of a century. The position of Chairman was held by the Lord Warden who at that time was George Leveson Gower Granville, 2nd Earl Granville (1815–1891), Lord Warden 1866-1891.

As sail was giving way to steam ships it was decided to widen the entrance to Bason and Finnis’ used this to persuade the Board to undertake major improvements to the dock. Work commenced in May 1871 with the demolition of the clock and the compass towers. The clocks were installed in the newly built clock tower, on the Esplanade in 1877. The entrance to Bason was widened to 70-feet, and the sill lowered to allow vessels drawing 20-feet at spring tides and 16-feet at neap tides to enter. The refurbished dock was opened by the Earl of Granville on 6 July 1874 and renamed Granville Dock. The aggregate expenditure was £74,416 13s 1d. The occasion was marked by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company’s paddle steamer, Maid of Kent, carrying passengers from Admiralty Pier into the dock, led by the harbour tug Palmerston, after an official lunch at the Lord Warden Hotel.

Dover was to all intents and purposes the Harbour of Refuge for ships in trouble in the Channel. The pressure on parliament to turn Dover into an official Harbour of Refuge had been ongoing since 1836. Throughout that time, the number of shipping catastrophes continued to increase and troubled vessels were brought into the new Granville dock. To pump seawater out of damaged ships, in 1887, steam pumps were erected on the quay and one of the first ships that the new machine was used on was the Leander of Bremen. She struck a sunken vessel in November that year. Shortly afterwards the barque Norman, was brought to the Granville dock following a collision off Lowestoft.

Besides dealing with shipping catastrophes, as the quays were wide, the dock was used by cargo vessels. Commensurate buildings, such as Bradley’s corn store where once the Ship hotel had once stood, were built. In 1894, DHB built two sets of warehouses alongside the dock to hold goods for ocean going steamers.

August 1899 saw a national dock strike and following a visit by flying pickets from London, men working on unloading timber at Granville dock went on strike. They demanded an increase from 4½d an hour to 6d but the demands were ignored. Instead, men were brought in by a private firm and they unloaded the timber under the protection of the police. Although the situation was eventually resolved, it caused a great deal of resentment by locals of DHB that was to last a long time.

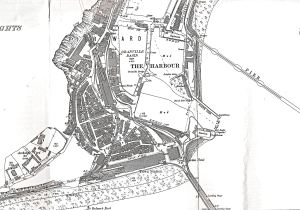

Granville Dock with Pier District on the left and Tidal Harbour on right. Archcliffe Fort is at extreme left. 1890

In 1912, the dumpheads were removed from the inner side of the dock entrance giving a longer quay that enabled the Clyde Shipping Company to use it as a berth. The following year, as work was being undertaken in preparation for possible war, the destroyer Kangaroo struck the quay badly twisting her stern and causing structural damage to the quay. In early November 1913, the Sixth Submarine Flotilla comprising C7 to C13, arrived and moored in Granville Dock.

Following the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) on 4 August 1914, the naval personnel built a floating repair shop in the Granville dock, using the shell of an old steel lighter belonging to DHB’s works department. Throughout the War, the dock was used for the repair of trawlers and cross-Channel ships. Railway materials for France were also loaded and shipped from the dock.

After the War DHB decided to utilise Granville dock for commercial activities and in particular, the coal and timber trades. They started in a small way at the end of the hostilities when the harbour was still in the hands of the Admiralty. However, by the time it was handed back to DHB, on 29 September 1923, the export coal trade was in decline due to the exchange rate out-pricing British coal. Nonetheless, there was a need for domestic coal in East Kent and for this there was gradual increase in the facilities for unloading coal from the north east of England. Following the 1926 General Strike imported coal from the Continent increased along with the arrival of coal from north America. Much of the latter was unloaded from berths on the Admiralty Pier. Over the following years other commercial activities including importing material for road building and bricks. The latter to meet the needs of Dover’s municipal housing schemes and Kent coalfield villages.

Yachts sometimes berthed in the Granville dock and in 1926 Police Constable Bill Griggs, 36, and colleagues, answered a call to a fire on the motor yacht Quo Vadis. Shortly after arrival, the yacht blew up killing P C Griggs. Two years later, in December 1928 at night, Police-Constable Steele dived into the dock to rescue Captain W J Thomson of the steamer Kenrix. Steele towed the unconscious man 40-yards to the steps of the dock where two other police officers rendered artificial respiration. Meanwhile, Steele dived in again to help a crewmember, James Huggeth, who had gone to help the captain but ran into trouble because of the cold. Huggeth was taken on board his ship and the captain to the Royal Victoria Hospital where he eventually made a good recovery.

In 1928 the Dover Harbour Board, sought parliamentary approval to close Commercial Quay, on the landward side of Wellington Dock in order to increase the size of the Dock and to create more quayside accommodation. The Dover Corporation opposed the Bill as it involved demolition of many of the properties between Commercial Quay and Snargate Street – Northampton Street. The Bill was passed in July 1929 and Wellington Dock was increased to 8 acres.

In preparation for possible war, during the night of 5 February 1939, an emergency was organised in which many of the town’s inhabitants took part. Arrangement had been made with RAF Hawkinge for aircraft to simulate attacking forces, but due to fog, they were cancelled. Nonetheless, the areas they had supposed to have attacked carried on with the exercise. The central control station was established in the basement of the then Town Hall (Maison Dieu) under the command of the Town Clerk, Samuel Loxton and all 70 wardens’ posts were manned by nearly 600 people with 50 motor vehicles. The police Chief Constable, Marshall Bolt and other borough officials, had drawn up hypothetical incidents.

The supposed attack included seven high-explosive bombs, two incendiary bombs, three mustard gas cases and a plane crash. The latter was supposed to have occurred at Charlton Green and set a house alight. At Granville dock an incendiary bomb was suppose to have set fire to a coal lighter and part of the quay causing two casualties. The alarm was given at 02.15hrs, within six-minutes the auxiliary fire fighters were on the scene, and the casualties were taken to hospital in an ambulance within 15-minutes. The feedback was that the communication had worked smoothly and that the results of enemy attacks on the dock could be dealt with.

The reality was far more serious than was envisaged. World War II (1939-1945) began on 3 September 1939 and from the start of the Battle of Britain, nine months later, Granville Dock became a prime target. On 8 October 1940, a 500kg bomb made a direct hit on the trawler HMT Burke under repair in the Dock. Eight people were killed including five Dover ship repair workers: Fred Stanford 18 of Clarendon Place, welder George Lamkin 18, of York Street, Cyril Playford 20 of Pilgrims Way, shipwright Arthur Young 33 of Endeavour Place and George Dewell of St John’s Road, Elvington.

However, such information was not made available for naval or army personnel so the other three casualties were not listed. Another example of this secrecy happened on Wednesday 1 October 1941, just before midnight, when a JU88 drop a bomb that set alight trawlers and motor launches in the Dock. The reports of damage and casualties were withheld, as were the many other attacks on Granville dock.

At about this time concern was being expressed over the Dock gates, fitted in 1874, they were wearing thin and there was a danger that they would not withstand many more attacks to the dock. In 1943 new mild steel, self-balancing gates, each leaf weighing some 67 tons, were ordered from Head, Wrightson & Co of Thornaby-on-Tees, Teesside. They were designed by Coode, Wilson, Vaughan-Lee and Gwyther and were reassembled off Admiralty Pier.

It was not until May 1945 that the Dock was emptied and an ancient caisson was fitted to keep it dry. The new gates were then floated across the harbour and fitted. Electronic winches with patent hydraulic couplings, the first of the type in the country, were installed to replace the original hand operated winches. Ransomes and Rapier of Ipswich made these; however, the original system of chain operation for opening the gates was retained. The whole cost nearly £35,000 and was the first part of a scheme to repair and modernise the dock.

The first export of coal following the War was in June 1948 from Granville dock. With a modicum of fanfare, a Dutch vessel left, taking cargo of screenings to Rotterdam. The following year permission was given to demolish Custom House Quay and Strond Street was realigned. This was to provide space for a massive transit shed on the north side of the Dock and large electric cranes were installed. The Dock became a cargo terminal for grain, fruit, vegetables, stone, timber, wood pulp, coal and scrap metal. In 1951, authority was given for the closure of Strond Street to provide more cargo space.

In 1966 that DHB demolished the last of the few remaining ancient buildings on Strond Street. This was Mrs Adamson’s shop, believed to date from Tudor times but had an attractive Georgian-like facade. No thought was given to moving it to another location for at the time, Dover’s elite decreed that the town was to be forward-looking. Modern office blocks were built but on 27 July 1972, the British cargo ship, Salerno (1,559 tons), hit the Granville dock quay on which stood a two-storey office block. The building was badly damaged but luckily, the office-workers managed to escape shaken but unhurt.

Albeit, some people were looking back and 26 May 1985 saw a flotilla of 30 out of the 500 boats that took part in rescuing the British Expeditionary Force off the beaches of Dunkirk in 1940, left Granville dock. They belonged to the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships, the founder and Admiral of which was broadcaster, Raymond Baxter (1922–2006). In 2000, to mark the 40th anniversary of the evacuation 40 little ships congregated in the Granville Dock, all flying the St George Cross, a privilege bestowed on the little ships that took part.

As cargo vessels became larger, the decision was made to create a berth at the Eastern Dock. With this in mind, in the early 1990s a major waterfront development plan for Western Docks was launched. The scheme was expected to cost £100m and included a yachting marina, blocks of luxury flats, a superstore, a 100-bedroom hotel and offices. The first phase was scheduled to start in 1994 with a superstore adjacent to Wellington Dock but requiring part of that to be filled in.

Once the cargo vessels were moved out of Granville dock, the plan was to turn it into a marina with space for 400 yachts. However, the redevelopment did not take place as the Environment Agency objected tothe development on the grounds that it could precipitate an increase in the unacceptable levels of flooding. Although much of the redevelopment plan did not happen, about £1m was spent on modifications and work on the gates, sluices and quay faces of the Dock providing space for about 136 yachts.

In 2006, another Western Docks regeneration plan was launched. This time to create a second ferry terminal with four new berths and a marina. A representative for the Dover Harbour Board said that ‘in thirty years the number of lorries using the port had increased by 530% to 1.98 million a year. It was forecast to double by 2034.’ With these figures in mind, ‘Dover is a freight port that handles lots of tourists, rather than a tourist port that handles lots of freight.’

At that time, there was talk of a buffer zone off the A20 between Folkestone and Dover, where freight vehicles would be held and released to the port as shipping space became available. The proposal is slowly becoming a reality and includes the widening of the Prince of Wales Pier in order to turn it into freight cargo berths. The freight lorries, it is envisaged, will be held on ‘reclaimed land’ – that is, the present Granville dock and the Tidal dock. In October 2015 Dover’s popular marina, which Granville Dock is part of, was awarded a Five Gold Anchor rating by the Yacht Harbour Association.

- Presented:

- 19 May 2014