Many cities and towns boasts of ancient markets and Dover is no exception. Markets developed out of Fairs and once upon a time Dover’s Fair was one of the most celebrated in the country. Fairs were originally religious festivals usually held in honour of the local patron saint and were a time of celebration as well as providing a day when hard working folk would dress in their finery, pray and celebrate. In Dover, the main church was St Martins-le-Grand, situated on the west side of Market Square, traces of which can still be seen from the Dover Discovery Centre steps.

Dover’s Holy Day, or holiday, was the feast day of St Martin of Tours, 11 November, and celebrations originally lasted three days. The event attracted large crowds from the surrounding countryside and possibly from across the Channel, with many bringing with them goods to sell. It was only a matter of time before codes of behaviour were introduced. Typically, an Act of Lothaire, King of Kent 673, stated that no persons should barter, except in front of a credible witness the penalty for so doing was thirty shillings and the forfeiture of the property to the superior, in whose jurisdiction the transaction took place.

There were then few, if any, local shops so it was only from the travelling salesmen who bought wares to these fairs that the people were able to buy such things as cloth and household utensils. As time passed towns introduced local controls but to add weight to these and to provide conformity throughout the country, a town would apply and pay for a warrant from the monarch. Dover received its Royal Charter around 1160 by which time St Martin’s fair lasted ten days and the Charter stated that it was not to get any longer!

However, the Charter effectively legitimised that Dover’s fair could last ten days that made it very popular indeed! Other restrictions included the revival of the ancient barter rule, which required such transactions only to take place in front of a credible witness, under the penalty of double the value of the goods sold and the loss of the trader’s booth. The Charter dictated with where the fair was to take place, when and the times of operation. The Corporation were also given the privilege of holding a court of Piepoudre, where disputes were settled and fines for misdemeanours were levied. This, the town was allowed to keep free of taxes.

By Edward I’s reign (1272-1307) fairs had a bad reputation so rules and standards were tightened. These included forbidding fairs to be held in church yards, the council have to state how much it would cost to hire a site and duration for a stall and what form punishment of offenders would take. It was also stipulated that councils had to state what could be sold and at what times and any bias, for instance in Dover local produce and livestock had priority over goods brought from further a field. From what is known of fairs at this time, there would have been food and ale-sellers, local craftsmen and itinerant peddlers the latter selling goods such as utensils and cloth that could not be produced locally. There would also have been a great deal of merry making.

For centuries Dover’s main industry was fishing, particularly herrings as they were part of the English staple diet. It was the sturdy little fishing boats built in Dover and the other towns that made up the Cinque Ports, which were called upon by successive monarchs when they went to war. In June 1278, Edward I besides granting Dover’s Fair Charter issued one encapsulating the role and function of the Confederation of the Cinque Ports. This effectively confirmed the Cinque Ports as England’s first true navy. In return the Cinque Ports were given a number of privileges including the right to dry fishing nets and to take control of the yearly Yarmouth Herring Fair. Dover’s Herring Fair was part of the 10-day St Martin’s Fair.

In 1479, the council decided that a half-year maletot (rate) should be levied on the town’s folk to pay for a new cross in Cross Place – the name for Market Square at that time. It was also decreed that in future the market for local produce and livestock, as well as St Martin’s Fair, should be held in the vicinity. Two years later, it was agreed that on market day merchants could sell butter, eggs, geese, capons, hens and chickens all day. Town’s folk could buy and sell corn between 08.00hrs and 12noon but strangers (non-townsfolk) were not allowed to buy or sell corn until after 16.00hrs. Butchers, drapers, mercers and others had to close by mid-day and to have left the market by 13.00hrs or they would be fined.

After the Reformation (1529-1536) saints lost much of their veneration in England but as Dover thrived on its fair Henry VIII (1509-1547) granted the Archbishop of Canterbury the right to hold three fairs in the town. These were St Margaret’s Day (19 July), St Bartholomew’s Day (24 August), and St Martin’s Day (11 November). The profits were, however, to go into the King’s coffers! Nonetheless, the Corporation still had the privilege of holding the court of Piepoudre from which the town could keep fines. During the reign of Mary I (1553-1558) it was decreed that the Mayor should have the power and authority set the prices charged in the Market. At about the same time the Corporation built at least four shops in or near the market place for which they charged 13s 4d (67p) a year rent. Whether they were taken up is not known but by 1569 the council had ‘improved’ the shops in the fish market. There the take up was poor, with only William Lovell, John Whetstone and Robert Bonyard mentioned by name as renting them. The fairs, however, continued to be very popular and entertainment had become an important part of the festivities.

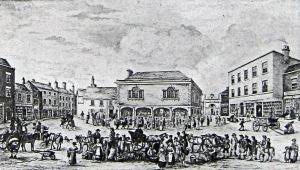

Court Hall 1606-1834 demolished 1841. The market was held underneath inside of the wooden pillars. Dover Museum

About 1500 the council considered building a place in which they could hold meetings and court sessions. At the time they were held in a building belonging to St Martin-le-Grand in King Street. Following the Reformation, the council laid claim to the site of what had been St Martin-le-Grand and on 6 July 1606 the order was given that a new building would be erected on the site where the Market Cross stood. The new Court Hall (also referred to as Council Chamber, Town Hall and the misnomer – Guild Hall), stood on wooden pillars carved with grotesque faces created by a local named Weekes. It was opened in 1607 with the business of the town taking place in the upper rooms and below, within the wooden pillars, meat, butter and vegetable markets were held. From the ceiling hung grappling irons and hooks, in case of fire.

James Hugesson gift of the Market Place and Court Hall etc. to the town published in the Dover Year Book 1874

Much to the surprise and consternation of the council, in 1633 James Hugesson (d1637), a wealthy merchant adventurer, claimed possession of the St Martin-le-Grand lands that included the site of the new Court Hall and market. The case was taken to the King – Charles I (1625-1649) – who upheld Hugesson’s claim. Once Hugesson was acknowledged as the owner he leased part of the site to the parish of St Mary’s for 1000 years to be used as a cemetery – St Martin‘s cemetery. The remainder of his lands were given to the town on the promise that £3 was to be given annually to six poor widows of Freeman. The land given included the whole Market Place, with the Court Hall and surrounding streets and buildings.

By the reign of Charles II (1649-1685), only St Martin’s Fair remained but as a way of thanks for the welcome the town gave him at the Restoration in 1660, he granted a fair for cattle, on the 23 and 24 April, and on the 25 and 26 September. The King also confirmed the St Martin’s Fair but to begin on 23 November with ‘piccage, tallage and toll’ and all other profits arising from the fairs to go to the town. However, much of the remainder of the Charter was so complex that it caused more problems than it resolved. Gradually many of the rules were abolished and replaced by more convenient ones for both buyers and sellers.

Towards the end of the 17th century St Martin’s Fair had become synonymous with the hiring of servants and labourers. Those looking for employment would gather around the Market Cross hoping to have a master seal their contract with the gift of a ‘fasting penny’, also known as a ‘godspenny. The value varied over time but the contract was binding to both parties. If either party infringed the deal they could be fined or imprisoned. This way of seeking work and hiring workers lasted well into the 19th century.

Over the next century, the different wares for sale and other attractions increased, as did the Fair’s popularity. The market under the Court Hall was held every Wednesday and Saturday, the latter being the principal market. On that day folk from miles around would come early into town to sell their produce. There was also a butter market in the same locality and a butchers shambles nearby.

By 1790 St Martin’s Fair started on 22 November and continued over the following three market-days (about 10 days). To accommodate the ever increasing size of the market the Corporation in 1826, promoted through parliament, the Dover Market Act enabling them to demolish part of the west side of King Street. The same Act provided for the removal of elections from St Mary’s Church to the Court Hall. In Buckland there was St Bartholomew‘s Fair on 24 August and the traditional date for Charlton Green Fair was 6 July. The latter was particularly noted for merrymaking until it ceased about 1840.

From late medieval times the land below the Western Heights had been drying out, a situation that was taken advantage of by mariners and became known as the Pier District. In a rate book of 1665, a Fisherman’s Street (later Middle Row) was listed and eventually a purpose built fish market opened near to where the Clock Tower stands today. This site proved to be so unpopular that the council were obliged build a new one that opened in what became known as Fishmongers Lane, near Townwall Street, on the same days as the main market under the Court Hall.

In the Royal Oak Yard – adjoining an ancient inn on Cannon Street – was Dover’s centuries old corn market. In 1861, it was of national interest due to a legal case. The year Farmer Gambrell bought wheat seed but later found that it to be giant sainfoin seed, which was not what he wanted. He could have also bought the sainfoin seed much cheaper elsewhere. He returned to the market and confronted Mr Terry, the merchant who sold him the seed and an heated argument took place that included strong language and insults. Terry took the matter to court accusing Gambrell of slander and Lord Chief Justice, Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn (1802-1880), heard the case. The Lord Chief Justice stated, in his summing up, that the case should be thrown out as both men were respectable and that the matter should be settled without recourse to court proceedings and recommended that both men shared the costs and go home. However, this was not acceptable to either party and the jury found for Gambrell. The corn market closed in 1893 when the Royal Oak was demolished to make way for the buildings on the east side of Cannon Street.

In 1886 a wholesale fish market was built by Dover Harbour Board near the Crosswall, adjacent to the Tidal Basin. In the early morning the ‘catches’ were sold by auction. However, the commercial fishing was starting to decline for in 1871, there were 21 first-class fishing vessels by then there was only 52 Dover registered (carrying the DR boat registration) fishing boats, employing 185 men. In 1906 only ten DR fishing vessels remained and four years later the numbers had fallen to five.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 22.06.2006