Dover’s first railway terminus, Town Station, was built by the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) and opened on 6 February 1844. The company had been given Royal Assent on 21 June 1836 and incorporated the Canterbury – Whitstable Railway that opened in 1830 and the London and Greenwich Railway that opened in 1833. The station was located on Beach Street, in the Pier District of Dover and was named Town station in 1863 even though it was closer to the harbour than the centre of town, nearly a mile away. Throughout the 19th century, the Pier District was the maritime area of Dover comprising of short streets that had been built on shingle banks, which had formed on the seaward side of Paradise Pent, a small harbour built at the end of the 15th century.

Besides Beach Street, the other main streets were, Great Street, Round Tower Street, Council House Street, Middle Row, Seven Star Street, Elizabeth Street and Clarence Place. Paradise Pent had long since silted up and had been replaced by the much larger inner harbour or Bason (later Granville Dock). Access to the sea from the Bason was through the Tidal harbour, the western side of which was Clarence Place. To the south of Clarence Place and east of Beach Street and the Town Station, the Admiralty Pier was started in 1847. With the coming of the railway, via the SER line to the Town station and the building of Admiralty Pier – planned at the time to be the Western Pier of a Harbour of Refuge – Dover had great hopes for the future. However, SER bought the derelict Folkestone Harbour in 1842 with the intention of turning that into their main passage port to the Continent.

SER had previously successfully applied for permission from parliament to build a railway line from London to north-east Kent, called the North Kent Line, and by 1846 had opened a track from their main London-Folkestone line at Ashford to Margate in Thanet. This was by way of Canterbury – now Canterbury West station – and Broadstairs. The following year they opened a spur from Margate down the east coast to Sandwich and Deal but discounted the need to connect Dover with either Canterbury or Deal. By 1849, SER had built their North Kent Line from London through Greenwich and Dartford to Strood but did not consider it economically viable to join this to the Canterbury – Margate spur.

In the meantime a second company, the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway, was set up in 1845. One of the committee members was Sir Brook W Bridges (1801-1875) of Goodnestone Park, Member of Parliament (MP) for East Kent in 1852 and again in 1857-1868. This company planned to lay a railway track from Strood to Ramsgate and join the SER lines at both ends.

The Canterbury and Dover Railway Company was floated in October 1845 to provide a connection at Canterbury with the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway from Dover. The company also planned to extend their line from Dover to Deal. The committee included Dover Aldermen – Roger Stephen Court, Charles Kesterman, Edward Rutley and William Sankey. Dover Common Councilmen – Josiah Hollyer and Edward Seward along with Benjamin Worthington and John Birmingham. One of their three bankers was Latham & Co of Dover.

At Rochester on 30 January 1850, the North Kent Railway Continuation Rochester to Chatham group held a meeting to sanction the proposition by the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway to connect with the SER line at Strood. They also proposed to sanction the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway to build a railway connecting Strood to Dover and Downs (Deal) via Canterbury. Both resolutions were unanimously agreed. On Thursday 9 June 1853, in parliament, the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway were given permission to construct a railway bridge over the River Medway, a railway line between Strood and Canterbury and a branch from Faversham to Faversham Creek. Although the Company had applied for running powers over the existing SER North Kent Line to London Bridge, due to strong opposition from SER, this was watered down to giving SER the power to treat the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway traffic as its own for a financial consideration.

While the Bill was going through parliament, the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway, in 1852, had amalgamated with the Canterbury and Dover Railway to form the Strood, Canterbury and Dover Railway Company. The directors were, chairman – Stephen Rumbold Lushington (1776-1868) who was born in Godmersham, Kent and was a former Governor of Madras (now Chennai). Deputy chairman – Canterbury Alderman David Salomons. The other directors were Philip Blyth, G T Braine, Charles Jones Hilton (1809-1866) – cement manufacturer of Court Street Faversham, Charles Manners Lushington (1819-1864) MP for Canterbury 1854-1857 and son of the Chairman, Edward Twopeny and Sir John Tylden. The supporting land owners and Members of Parliament (MPs) included George John Watson Milles, 4th Baron Sondes (1794-1874), George Francis Robert Harris (1810-1872), 3rd Baron Harris also a former Governor of Madras, Sir Brook Bridges, Dover’s MP Edward Royd Rice (1790-1878), Admiral George Hughes D’Eath of Knowlton Park, Steriker Finnis of Dover and John Birmingham in his capacity as the Mayor of Dover.

The Strood, Canterbury and Dover Railway Company proposed a 44-mile line from Dover to join the SER London-Strood line at Strood but when the Company applied to parliament to sanction their proposition SER vehemently objected. The company was dissolved and reconstituted, in September 1852, as the East Kent Railway Company, (EKR) under the Chairmanship of Lord Sondes and the Company Secretary George Augustus Frederick Charles Holroyd 2nd Earl of Sheffield (1802-1876). The rest of the Board was made up of the directors of the old company and the shareholders remained, on the whole, as before. One of the shareholders was a major investor in EKR, Thomas Russell Crampton (1816-1888). The company’s capital was £70,000 in 28,000 shares of £25 each and EKR made a great point of comparing their proposed mileages with those of SER.

Utilising the Act of 1853, EKR started by building a railway line between Strood and Canterbury under the direction of Thomas Crampton. Coming from Broadstairs, Kent, he had previously been a senior engineer with SER and had been involved in the laying of the successful England-France Submarine Cable. During his time with SER, Crampton had worked with engineer Edward Ladd Betts (1815-1872) who was born at Buckland, near Dover. However, Crampton had fallen foul of SER’s Consulting Engineer, Joseph Locke (1805-1860) on the subject of SER extending their North Kent Line from Strood to Margate and was dispensed with.

Laying the track from Strood by EKR was slow progress due to lack of finance but eventually, on 25 January 1858, they opened their line between Chatham and Faversham, with intermediate stations at Rainham, Sittingbourne and Teynham. The Rochester Bridge over the Medway to Chatham and designed by Joseph Cubitt (1811-1872), opened in March 1858 with an intermediate station named New Brampton – renamed Gillingham on 1 October 1912. The journey between Strood and Faversham took about 50 minutes instead of nearly a day by horse drawn coach.

In June that year, SER put forward proposals to amalgamate with EKR but due to concerns by SER’s own directors over the precarious financial state of EKR, the discussions failed. Therefore, EKR applied to parliament to extend their line from Strood into London by a separate route. SER knowing of EKR’s financial situation, did not offer any resistance. In October 1855, EKR held shareholders meeting to discuss extending the railway, when it was built, from Canterbury to Dover. In the chair was Brooke Bridges supported by the company secretary, Edward Knocker. Brooke Bridges made it clear that EKR planned to break SER’s monopoly over Kent and Knocker gave details of the population that EKR’s line would serve. He told the shareholders that including Dover and Canterbury and the villages in between, there lived 75,731 persons and estimated that collectively they would use the new line sufficiently to give EKR an annual revenue of £16,000. If the railway was connected to London, Knocker tentatively suggested, ‘where the population was nearly 2,500,000 persons, the annual revenue could be expected to be £30,000 from 150,000 annual passengers visiting the Kent coast or/and crossing the Channel!’ He went on to say that it was expected that with Dover’s Continental connections and goods traffic would provide significant revenue while a Deal branch would generate £6,000 per annum.

The Duke of Wellington had backed the idea of an alternative railway line between Dover and London to that of SER’s . Painting by John Lilley 1837. Dover Museum

In answer to questions, the directors stated that it was envisage that the railway, in Dover, would go under the Western Heights and a station would be built next to the harbour. There, the shareholders were told, the station would be in a sheltered position and from where the company would run a fleet of cross Channel ships. A Mr Taylor, then read out a letter from the deceased Lord Warden 1829-1852 the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), dated 3 November 1849. In the letter Wellington totally endorsed a railway line as proposed by EKR, saying that in the interest of national security there should be two separate railway routes from Dover to London. Emphasising, that he was particularly concerned over the vulnerability of the SER line between Folkestone and Dover. The resolution to go ahead with the construction of the Canterbury – Dover railway line was proposed by Dover’s MP Edward Royd Rice, seconded by the Mayor of Canterbury and carried unanimously by EKR shareholders.

EKR’s Parliamentary Bill of 1858, to extend their line from Strood into London was going through the process when, in July 1859, EKR re-designated their title as the London, Chatham & Dover Railway Company (LCDR). The Bill provided for a new line from Strood to St Mary Cray, where it was expected to connect with the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway Company at Shortlands – then named Bromley. From there, two possible routes existed for the Thames crossing, one was via Blackfriars and the other via Battersea. The proposed London terminus was to be at Manor Street, Westminster.

The Bill also included the proposed railway track from Canterbury to Dover with a spur from Dover to Deal. As had been discussed at the meeting of June 1858, the Canterbury-Dover the line would go under the Western Heights terminating at the harbour. LCDR envisaged making Dover their main crossing point for the Continent. During the parliamentary inquiries, representatives of LCDR emphasised that SER had chosen to make Folkestone their main harbour for the Continent and had created a monopoly to the detriment of the general public.

Among those who gave evidence on behalf of LCDR was Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge (1819 -1904). Shortly after being given Royal Assent in 1860, LCDR started work in earnest on both the Eastern and Western sections of their proposed operation, the centre section being the Strood to Faversham line. The first section of the Eastern operation was the laying of the line to Canterbury then to Dover. However, in Dover there was much opposition, particularly as homes would have to be demolished in the heavily populated Pier District. In January 1860, the Mayor of Dover, James Cuthbert Ottaway, called a public Common Hall meeting where Alderman Edward Knocker, Alderman James Wood, Councillor Baker, Rowland Rees, Reverend Briggs and Steriker Finnis all put forward the arguments for the line. The meeting concluded with agreement.

The branch line from Faversham to Faversham Creek was opened on 12 April 1860 and the line between Faversham and Canterbury, with an intermediate station at Selling, opened on 9 July 1860. The line from Canterbury to Dover was calculated to be just under 17-miles and until it was completed, LCDR laid on a regular horse drawn omnibus service. Advertising that there would be three omnibuses a day leaving Dover for Canterbury, the first class fare between Dover and London was 11shillings, 2nd class 9shillings and third class 7shillings. The omnibus service made strategic stops at villages where LCDR proposed to open railway stations in order to attract passengers. Four intermediate stations were planned, they were Bekesbourne, Adisham, Shepherdswell and Kearsney before Dover Town station as LCDR decided to call their Dover station. In 1863 LCDR changed the name of the station to Dover Priory.

The track was through undulating terrain requiring cuttings, embankments, bridges and tunnels. The bridges were chiefly over or under country roads and were all built of brick. There were four tunnels but as the line was principally going through compact chalk, it was believed, that once consolidated these would be easily maintained. From Canterbury to Bekesbourne, the distance was some 3 miles. Using an engine with 32 trucks attached to carry and remove materials, all was going well. By the 19 January 1860, a bridge plus a lengthy embankment had been built but at 17.00hrs, not far from the village of Bekesbourne, men were working in one of the cuttings when one of them realised something was amiss and rang the danger bell. Most of the men were out when some 100-tons of earth collapsed into the cutting burying three men and a horse. Following the accident, measures were taken to erect more substantial boarding in an effort to stop further such accidents. The station at Bekesbourne was/is situated between Bekesbourne Hill and the village itself.

At this time men had already been working on the next section of track to Adisham station, approximately 7-miles from Canterbury. On this section another high embankment was required plus a bridge with two arches. Adisham, at this time was a quiet rural village on the west of the line but this changed in the early part of the 20th century with the coming of the Kent Coalfields, the opening of Snowdown Colliery and the village of Aylesham with its own railway station. Back in 1860 the next station down the line after Adisham was Shepherdswell or Sibertswold as the village was originally called. The name Sibertswold had been change to Shebbertswell by the end of the 18th century and during the early part of the 19th century, to Shepherdwell, yet a myth exists that it was LCDR that changed the name. Although a station was not built at Lydden, to get there from Shephersdwell, LCDR were required to excavate a 2,376yard tunnel. The compact chalk meant that the tunnel was completely dry throughout the time the men took to brick it with cement throughout.

After the tunnel, the line passed to the east of the village of Lydden. The next village was Temple Ewell where a viaduct was erected across the Lower Road just before the line reached Kearsney Station. This was built with a small goods siding and platforms for passenger trains to serve the villages of River and Temple Ewell or Ewell as the station board states. Immediately after leaving Kearsney station a bridge had to be built to cross the road leading to Kearsney Abbey. Running along the high ground on the east side of the village of River the line passed over two bridges at Crabble and remained on the high ground to the west of St Andrew’s Church, Buckland. Taking the line into Dover required the erecting of bridges and the excavating of two tunnels. The first tunnel, of 200-yards in length, was between Buckland Bottom and Tower Hamlets and the second, of 125yards, between Tower Hamlets and Dover Priory Station.

Map of Dover showing the railway line from Crabble to the harbour. Alan Young of disused-stations.org.uk

Between the first and second tunnel was the growing working class district of Tower Hamlets where there lay an obstacle that LCDR had not budgeted for. The access road to Tower Hamlets, at the time call Black Horse Lane, was a gradual incline from the London Road/High Street cross roads. LCDR intended to make it a level crossing but because of the population growth of the area, the Board of Trade insisted on a bridge over the railway lines. It was estimated that this would necessitate a stiff gradient of 1in7 so the road was curved southward giving a gradient of 1in13, which satisfied the Board of Trade. Shortly afterwards the name of the new access was changed to Tower Hamlets Road.

Dover Priory railway station opened on 21 July 1861 as the temporary terminus of the LCDR. Services started immediately and although the facilities were basic, the railway staff did everything they could to improve the situation. Until the station at the harbour was built, the company laid on four-horse omnibuses, leaving their office in Strond Street, near the harbour, to meet the 07.50hours, 10.50hours and 16.15hours trains on weekdays and on Sundays at 10.15hours, 12.30hours and 16.15hours. The booking clerk was George Gillman.

To take the line through to the harbour, it first had to cross the Folkestone Road. Although at the time there were few properties along the road, the notion of the railway brought in a proliferation of property developers. With this in mind and the extra expense that the Tower Hamlets bridge had cost, LCDR decided to erect a bridge using the natural shape of St Martin’s Hill and this was completed in 1861. To complete the line, the 684-yard tunnel under the Western Heights was excavated.

Before reaching the Pier District the line passed through the caves and land of the Oil Mills on Limekiln Street. Owned by Robert Walker, he accepted compensation from LCDR and then sold the land east of the track back to the railway company who eventually built their Bonded warehouse on the site! It had originally been intended that the line would cross Limekiln Street by a level crossing but this required the demolition of four houses belonging to Dover Harbour Board. They took legal action but had to accept LCDR’s plans and were compensated.

By 1861, the second stage of the Admiralty Pier was almost completed and LCDR, in their evidence to parliament for the Dover section, had suggested running their track along Admiralty Pier where they would build a station. SER had previously sought permission but as the Pier was not completed, neither of the companies were given permission. Therefore LCDR selected a site for their terminus adjacent to the harbour as near as possible to Admiralty Pier. The site chosen was on Elizabeth Street and required the demolition of properties there, in the adjacent Round Tower Street and the nearby Council House Street. At the western end of the harbour was the Crosswall were a regular fish market was held. To persuade the council to move the market further east along the crosswall was only achieved when compensation was given. However, the paying of compensations was taking its toll on the LCDR’s finances and to reduce it in Dover, LCDR argued that the properties being demolished were old and unsanitary.

Albeit, Dover’s Roman Catholic community held out over their priests’ house and LCDR were forced to pay £650 when it was demolished. The Roman Catholic Chapel opposite the new station, for which they expected greater compensation deal, remained. The Anglican community were persuaded to allow the demolition of the Parish’s Holy Trinity Church School built in 1847. Their agreement provided £50 per annum in perpetuity from LCDR towards a new school. Lessons, until the new school was built, were held in the Ship Hotel on Custom House Quay. However, as the new railway station attracted businesses to the Pier District that put up the cost of building land, the Parish was unable to afford any land.

In 1867, LCDR provided land on the corner of Hawkesbury Street where a new school was built. Also suffering, but without a thought of compensation, were the men who had worked on the building of the line. On completion they were out of work and although many left the area to work on railway lines being built elsewhere, a considerable number had homes and families in Dover. For those who could not find work, they and their families faced destitution. To try and combat this, the Also suffering were the men who had worked on the building of the line but were now unemployed. To provide some work, Dover’s Mayor, John Birmingham instigated the widening of what was then Love Lane, now Barton Road. It was not until the 1880s, that the road was developed, as we know it today.

Possibly due to the lack of finance, it was decided to wait before building a permanent harbour station and so a temporary structure was erected and opened on 1 November 1861. The company immediately named the terminus as Harbour Station and boasted that luggage would go straight onto the ferries at the same time as the passengers. Making the point that passengers using the SER trains had to carry their luggage to the ships. Local townsmen, who had previously been running daily horse drawn omnibuses to Canterbury and London, changed to offering regular services from the harbour to various locations in Dover and surrounding villages.

The temporary Harbour Station was replaced with a permanent structure, some of which can still be seen today and has been given Grade II status. The building was designed by J R Jobbins and was originally dominated by an ‘Italianate’ style clock tower and was especially built, so it was said, because SER did not have a clock tower. Passenger washing facilities with running water and lavatories were part of the fixtures unlike SER’s Town Station of that time. However, as most of the neighbouring households had to make do with water pumps, local women would arrive with both their dirty laundry and dirty children and make full use of the facilities! Although attempts were made to try and stop this practice, there are reports that it was still going on up to World War I (1914-1918). The station also had a refreshment room and later Spiers and Pond, who pioneered national railway catering in the UK, won the contract.

With the building of Harbour Station the clocks in Dover were then set by the Station clock. Up until 1840, time was decided at the local level, usually by a church clock. That year the Great Western Railway Company had introduced Railway Time that synchronises railway clocks on each of their stations and enabled the railway companies to produce accurate timetables. Following Great Western’s lead Railway Time was adopted by all the individual railway companies and in accordance with that set by the Royal Observatory at Greenwich – Greenwich Mean Time. Unfortunately, the Harbour Station’s tall Italianate ornate clock had the obstinate tendency to be slow! This led to a businessman bringing a successful court action against LCDR after he missed his train. The clock hands were removed and never replaced but the tower remained. After the building of the adjacent Train Ferry Berth in the 1930s the tower was truncated and a light was fitted on the top to guide ferries into the berth.

LCDR’s rolling stock was painted black and to save money much of it was bought through Messrs Lucas Brothers who built many of the LCDR railway stations, including Harbour Station. EKR had bought second hand locomotives or borrowed from the Great Northern Railway, small Hawthorn engines. In 1858, they had ordered six new 4-4-0-saddle tank locomotives from R and W Hawthorn of Newcastle Upon-Tyne, but they too were small and also unreliable. William Martley (1824-1874) was appointed in 1860 as LCDR’s Locomotive Superintendent and immediately established the Longhedge railway works Stewarts Lane, Battersea. This opened in 1862 but due to money being spent on new railway lines, the work was mainly repairing and rebuilding a variety of engines, including the specially ordered Hawthorn engines.

The railway between Faversham and Ramsgate in Thanet, was built between 1860 and 1863 with the first 11-miles to Herne Bay having been completed by LCDR as a single track line. Whitstable, the first station, opened on 1 August 1860 and Herne Bay opened on 13 July 1861. The Margate and Ramgate section opened in 1863 with two intermediate stations at Birchington and Broadstairs. The sections of this 27-mile line were undertaken by different companies set up by LCDR under an agreement by which LCDR received half the receipts up to £45,420 and thereafter one quarter of the gross receipts. LCDR also paid the joint companies a rent of £45,000 per annum. Although the companies amalgamated as the Kent Coast Railway they were not formerly incorporated until 1865.

Map of the London, Chatham & Dover Railway Metropolitan Extension – Eastern Section C1865. Dover Museum

The Western Section of the LCDR railway line consisted of group schemes all requiring different Acts of Parliament and collectively called the Western and London Extension. Later this was divided into two, the Eastern and Western sections of the Metropolitan Extension. In the 1860 Act of Parliament it had been envisaged that LCDR would build the track from Strood to St Mary Cray, where it was expected to connect with the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway (WEL&CPR) at Bromley/Shortlands. From there, two possible routes existed to the Thames; one was via Blackfriars and the other via Battersea. On assessing the route from there on, LCDR had worked out that 17 individual sections of line would need to be built connecting to existing or proposed lines operated by nearly as many individual companies.

The first part of the Eastern section of the Metropolitan Extension was between Strood and St Mary Cray. This had actually been proposed under a Parliamentary Bill of 1856, which failed but two years later it received consent. The next section westward was from St Mary Cray to Bromley/Shortlands and this required going cap-in-hand to the Mid-Kent & North Kent Junction Railway (Mid-Kent Company). The Mid-Kent Company had formed in 1855 to construct a 7.5-mile line between the SER line at Lewisham and WEL&CPR at Beckenham. The line opened in 1857 but under a ten-year agreement with the Mid-Kent Company, SER, held running rights to the Shortlands/Bromley Junction at Southborough later renamed Bickley.

SER opposed LCDR running their trains along this part of the track so LCDR circumvented the problem by successfully applying to parliament for a separate line between Shortlands/Bromley Junction and Bickley/Southborough. The arrangement was made for the Mid-Kent Company to lay it, but it took two years to build the 2miles 30chains single track. This was leased to LCDR on 1 September 1863 for 999years. Altogether, the ownership of the 20miles 54 chains Strood -Bickley tracks were merged into the General Undertakings of the LCDR by the 1859 Act at a perpetual rent of £28,000 per annum.

The WEL&CPR Company had built a line between Crystal Palace and Wandsworth that opened in 1856. Two years later they had extended the line to Pimlico – which was, in fact, Battersea Wharf on the south side of the Thames. In 1857 WEL&CPR, had laid a track to Norwood then to Beckenham Junction building a short-lived station at Penge. LCDR had inherited the running powers over this section of track from EKR and later bought it. However, because of the EKR contract, in 1862 LCDR faced legal claims appertaining to land at Penge. This was the first of much major land litigation that LCDR was to fight over the next few years as they ventured into London. These were to be a significant strain on their financial resources. In 1859, WEL&CPR sold their line from Norwood junction to Pimlico/Battersea Wharf to the giant London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR).

LB&SCR was formed in 1846 by the amalgamation of the London and Croydon Railway Company and the London and Brighton Railway Company which had opened in 1837. Initially, it was envisaged by LCDR to join with the LB&SCR at Beckenham Junction. From there, they expected to enter London by way of Herne Hill, bridging the Thames to Blackfriars where they would open their London terminus. LCDR, with a grand scheme in mind, bought land in the expectation of connecting with the Metropolitan Company Railway in the heart of London. In the meantime the LB&SCR had sought a site for their London terminus opposite, Battersea Wharf on the north side of the Thames and LCDR decided to go with that. A loose amalgamation of four railway companies – LB&SCR, LCDR, Great Western Railway and the London and North Western Railway floated the Victoria Station and Pimlico Railway Company (VS&PR) that was given Royal Assent in 1859. The purpose of VS&PR was to provide a crossing of the Thames to a new railway station with the working name of Grosvenor Terminus that became Victoria Station.

The 930-foot bridge across the Thames, costing £84,000 and now known as Grosvenor Bridge, was designed by John Fowler (1817-1898). It originally had 5 spans and carried two lines – each of a separate gauge. The cost of the project was split equally four ways. Victoria Station was formerly opened in 27 March 1858 and on 1 November 1861, LCDR ran their official train into the station to open their ‘section’. However, the relationship between the Great Western Company and LB&SCR/LCDR Companies was far from amicable and the latter two decided to build an additional adjacent station – also called Victoria Station. This opened on 25 August 1862 but as LB&SCR was the senior partner in the transaction and LCDR were running their trains over LB&SCR’s last 15miles of tracks, be it at a continually increasing rental, LCDR agreed to pay two-thirds of the costs. Further, the new station required the Thames bridge to be widened to carry an additional two more lines. The cost was £245,000, which was paid for by LB&SCR/LCDR and divided in the same way as the new station!

A branch line had been opened from Strood to Maidstone in 1856 and from Swanley to Sevenoaks opening on 2 June 1862. Known as the Sevenoaks, Maidstone & Tonbridge Line it was a distinct corporate body with the legal power to build a 15miles 30chains extension between Otford and Maidstone. Incorporated as a General Undertaking by LCDR under the 1859 Act, they paid £11,500 rent per annum to the Sevenoaks company. In 1860 the Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway Company in association with LCDR built an 8miles 5chains spur from the Strood-Faversham line to the naval base of Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey. This included an intermediate station and pier at Queenborough, a flourishing port for Holland and northern Europe. The contract included a road bridge with tolls over the Swale, between the Isle of Sheppey and the mainland. Opening on 19 July 1860, LCDR leased the line from the company at £7,000 per annum until the two companies merged in 1876.

The building of the LCDR lines in Kent up to Beckenham Junction had thus far been undertaken by engineers Crampton and Frederick Thomas Turner (1812–1877). However, for the Metropolitan Extension lines and stations as well as the bridge over the River Thames to Victoria Station, LCDR had given the contracts to Peto & Betts together with Crampton. Samuel Morton Peto (1809-1889), known as Morton Peto, he was an engineer and entrepreneur who had joined with Crampton’s old associate, Edward Betts, in 1848 to form their own company. Together, Peto & Betts had worked on numerous of railway contracts and for the most part they were paid in debentures and shares. Debentures were paid bi-annually at a fixed interest rate on the face value of the debenture. Shares came in several categories and the number bought determined the percentage of profits the owner received. Shares could be sold and the price paid depended on what they appeared to be worth in relation to the company’s profits. Debentures provided Peto & Betts with a regular income while they could, and did, sell the shares at a later date when they were worth a higher price than the face value.

London, Chatham and Dover train on Admiralty Pier, the Lord Warden Hotel is on the right. Dover Museum

In the same year LCDR had arrived in Dover, 1861, the Dover Harbour Board was reconstituted. The Lord Warden still retained the chairmanship as it was written in the original Charter of 1606. The new change appertained to the Board that replaced the Commission. This was to be made up of two burgesses (senior councillors or aldermen) of Dover elected by the town council, and one nominee each of the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Board of Trade and SER. Although SER had moved two of their cross Channel ships, the Princess Clementine and the Princess Maud, from Folkestone to Dover this was to do with other reasons than the reconstituted Dover Harbour Board. In October 1861, SER had started running trains onto the Admiralty Pier, but the best position, Berth 2, was designated strictly for the sole use of mail trains and Joseph George Churchward‘s (1818-1890) packet ships. Although SER had the contract for the mail trains, when they found that the lucrative Dover packet contract was not due for renewal until 1870 they moved their two ships back to Folkestone in April 1862.

As part of their plan to take the line to Dover harbour, LCDR floated a subsidiary cross Channel passage company, named the LCDR Steamboat Service. The supervisory responsibility was given to engineer, William Martley (1824-1874) and over the next few years the paddle steamers, Samphire, Maid of Kent, Scud, Foam, Breeze, Wave and La France were built for the company. Much to Churchward’s chagrin and SER’s surprise, the Dover packet contract was advertised in December 1862 to come into operation from 21 April 1863. Churchward instigated legal action and although he was legally correct the evidence was overruled by the Solicitor General, Roundell Palmer 1st Earl of Selborne (1812-1895) and upheld by the House of Lords. By this time it was expected that SER would win the packet contract and that it would be moved to Folkestone to the detriment of Dover. However, LCDR put in a lower offer than SER, saying that they could run service for £13,000 a year out of Dover. They were successful and it came into effect on 20 June 1863.

Churchward agreed to transfer his steamboats, offices and packet yard to LCDR for £120,000, paid in instalments of £7,000 until 1870. The £7,000 per annum was made up of cash, preference shares and debentures bearing 5% annual interest. LCDR also agreed to pay Churchward an annuity of £800 per annum to 1870 for the Belgium-Britain packet contract, which he held until that year. Although well satisfied with the transactions, LCDR Directors decided to put the Dover-Deal railway project on hold until 1870. The ships sold to LCDR by Churchward were Vivid II, the former Garland name changed to L’Alliance to comply with an earlier French packet contract, Jupiter and the Prince Frederick William. They bought the former Churchward packet ships Empress and Prince Imperial which Churchward had sold to the French and later LCDR acquired the 123-ton Queen from the French and changed her name to Pioneer.

Having the packet contract and because of it, Berth 2 on the Admiralty Pier, LCDR petitioned to build a connecting line from Harbour Station. This was agreed but between the Station and the Pier stood the highly ornate tall and very solid Pilots’ station. This had opened in 1848 and was also a major tourist attraction. Money was getting short, and following the advice of their engineer Crampton, the ground floor of the tower, with a ceiling height of 20ft (over 6 metres), was gutted and the LCDR line laid through the Tower – which increased its interest as a tourist asset!

From the Pilots tower LCDR’s line ran onto the Pier on the harbour side of the SER line until a central crossover was reached. This enabled trains from both companies to run along side the long single platform that was against the western parapet. During south-westerly storms, which are not uncommon to Dover, waves broke over the parapet soaking railway passengers and their luggage! LCDR were given the southern part of the platform near to Berth 2. On the first day that LCDR started to run trains onto Admiralty Pier, 30 August 1864, Prince George, the Duke of Cambridge and his wife, Princess Mary, having travelled from London on an LCDR train, embarked on the LCDR steamer Wave for France. LCDR used the event for publicity purposes, saying that Royalty had opened the Admiralty Pier line!

Back in 1862, before SER had moved their two ships back to Folkestone, they suggested to LCDR that the two companies should form what became the Continental Agreement to avoid duplication of shipping services. Indeed, they gave this as their justification for moving their ships back to Folkestone. The general idea of the Continental Agreement was for all the railway receipts from every Channel passage port between Margate and Hastings to be pooled and then divided. As SER was the established Channel passage company they would have 70% of the receipts and LCDR, as the new comer, 30%. This was to last for ten years and thereafter the ratio was 60%-40%. The Directors of LCDR agreed and a Bill was presented to parliament.

Continental Agreement ratified August 1865 dividing the receipts of South Eastern and London, Chatham & Dover cross Channel shipping services

Not long before James Staats Forbes (1823-1904) was appointed the General Manager of LCDR. He clashed with the company’s Board of Directors when he suggested that the Continental Agreement proposal should be rescinded. Forbes was reminded that he was merely an employee but as the Bill progressed through parliament, he did manage to make amendments. The final agreement, ratified on 10 August 1865 was for the percentages to start from 32%-68% in 1863 and progressively closing until 1872, when they would be 50%-50%. Payments were half-yearly and came into operation immediately. By 1865 SER were promoting their company as THE cross Channel port, at Folkestone. To get round the Continental Agreement they built the attractive new Shorncliffe station (now Folkestone West) at Cheriton as this would not be subjected to the levy. However, Forbes did get his own way when he brought in the young William Robert Sykes (1840–1917), to train under him in order to take charge of maintenance of LCDR’s telegraph instruments, clocks, watches and lighting.

In December 1863 Lord Sondes, the Chairman of LCDR, laid the foundation stone of the Clarence Hotel, on the corner of Townwall Street and Woolcomber Street, built by the Clarence Hotel Company. The directors of the company included Steriker Finnis and Rowland Rees, both local men and major shareholders of LCDR. John Wichcord (1790-1860) designed the hotel, and when it finally opened in 1865, five-storeys with 240 rooms had been completed. However, the building was not finished as the owners had over reached themselves. Eventually it was demolished and the famous Burlington Hotel was built on the site.

In the days of the EKR the ultimate ambition of the company was to run a railway service between London and Paris with connections throughout England. This was to be achieved by building the railway to Dover, running a packet service across the Channel and teaming up with the French railway services. A second part of the vision was for the port of Dover to be a cargo terminal where goods from all parts country would be sent abroad or imported and taken to London by EKR railway. This same scheme was the goal of LCDR’s activities as they had built railway to Dover and set up the cross Channel service. The next part of the scheme was to build a massive depository on the Thames embankment, with its own wharf and near their London railway station. This depositary or warehouse was to be used as a holding area for goods waiting to be moved onto trains or lighters – the latter transported goods to or from the larger cargo ships moored on the Thames.

At the time horse drawn heavy vehicle traffic was used to carry goods between the different London railway stations and lighters. Thus, the Board of LCDR reasoned, the project – the Metropolitan Extension – would ease the congestion clogging up the streets of London especially if they could get all the large railway companies to utilise the service. Not long after LCDR was formed they had sought and received, in 1860, the Act for the Metropolitan Extension. In 1862 the Board gave the project contract to Peto and Betts in partnership with Crampton and it was estimated to cost £5.979million.

Before the decision had been made for Victoria Station to be LCDR’s London terminus, the company had been considering building a terminus further east, in the area of Blackfriars and they had planned to enter London by way of Herne Hill, crossing the Thames near London Bridge to Blackfriars. At the time and for a while after, LCDR bought land in the expectation of building this line, which included connecting with the Metropolitan Company line in the vicinity of Farrindon Street. That company had already laid lines to Kings Cross station, to connect with the Great Northern Railway and to Paddington station to connect with the Great Western Railway. These connections were part of the World’s first underground railway that the Metropolitan Company opened in 1863.

Joseph Cubitt, who had designed the Rochester Bridge, designed LCDR’s bridge across the Thames at Blackfriars and this was opened on 1 June 1864. Land had been bought nearby and the construction of the warehouse started shortly after. A railway route between the warehouse and Victoria station, to the west, was laid looping round via Brixton and Clapham using, as far as possible, lines already belonging or leased to LCDR with the company laying the rest. A second route was built between the warehouse and London Bridge Station to the east. To the north a line was to be laid to Farringdon Street to connect with the Metropolitan railway. In preparation, LCDR bought the site of the old Fleet prison for £60,000, the prison was infamous for incarcerating debtors and was demolished in the 1840s.

From the existing main line to Beckenham, as had originally been planned, a new line north was laid to Herne Hill. However, between Penge and Sydenham required the construction of a 2,290-yard tunnel. Some 200,000 cubic yards of heavy clay had to be removed and although much of it was made into bricks to line the tunnel it was an expensive, time consuming operation. The connection between Herne Hill and Blackfriars required Acts of Parliament and reached the Elephant and Castle on 6 October 1862 and eventually, on 21 December 1864, Blackfriars station.

However, for the last stretch, the line had gone through the heavily populated Southwark demolishing a lot of working-class homes and in neighbouring Lambeth 141 homes were demolished in one week, displacing 750 people. The homeless were forced to move away from London and from their work. To help deal with the problem, Forbes, initially without Board approval, offered to carry workers a distance not exceeding 10-miles into London for 1-shilling a week. In the autumn of 1864, Forbes reported that LCDR had carried 3,688 working men, the receipts being 5shillings 6pence per train mile while the expenditure for LCDR was 3-shillings 7pence per train mile.

Prior to arriving at Blackfriars Station, the line crossed the Thames on the newly built Blackfriars Bridge, and then continued north to Ludgate Hill. On this section litigation and associated costs against the company escalated, nonetheless, the station opened on 1 June 1865. From Ludgate Hill, LCDR had planned to build a line to the site of old Fleet Prison, on which Peto and Betts had already built a station and offices. However, the Metropolitan Company had built their Farringdon Street station nearby. In 1864, the City Undertaking Act came into force that sought to limit railway extensions through London without just cause. Metropolitan Railway had already agreed to lay two lines between Farringdon Street and Kings Cross station, for which Great Northern Railway had paid. To get round the Act and build the line to Farringdon Street, members of LCDR Board floated the City Lines Company to which Great Northern Railway loaned £300,000. LCDR in the name of the City Lines Company built a line from Ludgate Hill that joined Farringdon Street – Kings Cross line near Earl Street.

London, Chatham & Dover advert for their cross-Channel service with a mention of the connection to Crystal Palace. Dover Library

The success of the Metropolitan Extension project required the cooperation of several different railway companies requiring separate Acts of Parliament. However, at the time there was a proliferation of Bills in parliament, typically, in 1862, although Crystal Palace, in south London, already had an excellent train service provided by LB&SCR, a new company, the Crystal Palace & South London Junction Railway was given Royal Assent. The proposal was to be a branch line to Crystal Palace from LCDR main line at Peckham and was to have 5 stations. This had the backing of LCDR and was mentioned in their adverts.

By the end of 1863, many more Bills were still going through the parliamentary process. These included a 2½-mile track between Greenwich and Woolwich, estimated cost £200,000, another line of over 6-miles costing £420,000 and a track of just over 14-miles between Epsom and Sutton estimated to cost £400,000. The logic of why LCDR were involved in the latter two was lost on most LCDR debenture and shareholders.

To end the unrest, Morton Peto joined LCDR Board as financial advisor in December 1863. Immediately there was a clash between him and Forbes, who as the general manager, was forced to concede to Peto although he did manage to stop two other lines of doubtful use being built. Peto then put forward an ingenious proposal by which he would fund a floating debt of £1.25 million that would enable the company to issue more stock. These sold quickly and LCDR were able to raise more cash by issuing debentures.

In June 1863, with Lord Harris the deputy chairman presiding, the LCDR Board voted to issue common fund shares to the value of £750,000 and to borrow a further £250,000. Lord Harris had been the Governor of Madras who had returned to England in 1859, bought shares in LCDR, was appointed a director and then deputy chairman. The funds were to extend the Greenwich line, the Metropolitan Extension lines to London Bridge and to undertake improvements at Victoria Station. On Forbes taking up the position of general manager, he suggested that all of the various railway companies in Kent, in which LCDR had significant share holdings, be consolidated. The LCDR Board agreed and in November 1863, Mid Kent Railway Company was dissolved and became part of LCDR. In February 1864, with Lord Sondes in the chair, LCDR reported that the accounts for the final six months of 1863 showed that £3,984,947 had been spent on main line services, £4,586,883 on the Metropolitan Extension and £23,713 on shipping from Dover. From the main line services £171,086 had been received, from the Metropolitan Extension £30,928 and from Dover shipping £34,516. It was resolved that the company would not be paying dividends but finished by complimenting themselves, Peto & Betts and Crampton on how well LCDR was doing.

Mr Shaw, a shareholder from Dover, responded by saying that in his opinion, the Directors were in no position to congratulate themselves! ‘The company had started with £700,000 capital from shares and borrowing,’ he said, ‘and this now stood £9,000,000! In his opinion shareholders should employ counsel in Parliament to protect their interests.’ Shaw went on to say that the Dover shipping operation was the only part of the company that was profitable and that since LCDR had taken over the packet service, the number of passengers carried was 123,053. ‘Yet’, he said, ‘Dover was being badly treated by LCDR.’ The Company Secretary, the Earl of Sheffield, on behalf of the Board, responded saying ‘that until the connection between Admiralty Pier and the Metropolitan Extension was completed, there was little point in spending anymore than necessary at the Dover end.’ Rowland Rees, at the time Dover Harbour Board’s surveyor, agreed with Holroyd, saying that ‘once the Extension was completed, an enormous amount of traffic would come through Dover and it would be then time to expand the Dover terminus.’

LCDR’s first major rail accident occurred on 26 September 1864, when the fast train to Dover was traversing a low embankment after leaving Penge station. For reasons unclear, the engine left the track and plunged down the embankment dragging with it a second class carriage and another carriage. In the second class carriage were four passengers, all injured. The first class carriages, with some 30 passengers on board and the guards van stayed on the track. The guard returned to Penge station and after telegraphing London a relief train was sent to take the 30 unhurt passengers to Dover. The injured passengers, driver and the stoker were treated at the scene. In November 1864, with Lord Sondes in the Chair, LCDR agreed to raise £100,000 by the issue of shares and borrowing £33,000 by means of a debenture issue. This was to pay for a double line between Sevenoaks and Tonbridge and creating a junction with SER railway there. On 11 January 1864, SER had opened Charing Cross Station as their main London terminus.

On 15 November 1864, a shareholder of both LCDR and LB&SCR sought to bring a legal action against the Chairman of LB&SCR, Leo Schuster (1791-1871). Travelling on a train out of Victoria Station, both the applicant and Schulster were in the same 1st class railway carriage. Not long after crossing the Thames Mr Schulster opened the door of the carriage and jumped out. Concerned, the passenger reported the incident at the next station only to be told that Mr Schulster frequently joined and left the LB&SCR trains in such a manner and was of no concern.

Following unsympathetic reaction to his complaint to LB&SCR management, the passenger complained to LCDR as they ran trains on that part of the line. Forbes encouraged the passenger to take legal action, which was successful. This rested on Forbes, when he told the court of the case of 16-year old apprentice, Hugh Brown. The previous April, Brown left a train while it was entering Victoria Station and fell but did not sustain any injuries but it was against the law and Brown was arrested. Brown’s mother, a widow with four other children, worked in a laundry. Therefore the court was lenient and fined Hugh Brown 5-shillings. This was a lot of money for the Browns and therefore, Forbes suggested, Schulster should pay a fine of equal magnitude to his income. The relationship between LCDR and LB&SCR then went into freefall!

The half yearly report ending on 31 December 1864 stated that receipts on the 72½ miles of main line track amounted to £182,240 compared to £136,551 for the same half the previous year and £102,957 for the corresponding period the year before. The receipts derived from the cross Channel traffic £32,352 and expenses £19,156, while the expenditure on the main line between Bickley and Dover was £4,443,602 and for the Metropolitan Extension £5,451,886. In April 1865 LCDR were summoned before the Kingston Assizes for poor quality workmanship of the Metropolitan Extension bridges over roads in Newington. The bridges, it was alleged, were unfit for the passage for propulsion, not water tight and were dangerous to those passing underneath. LCDR denied negligence but did say that they would undertake remedies.

Emanuel Sochaczewski on 26 March 1865 died from injuries received after falling between carriages at Harbour Station and was buried in Cowgate Cemetery – AS 2012

The previous month, on 11 March 1865, John Hart age 48 was killed in the tunnel under the Western Heights. A labourer, he had previously worked for SER, where he had lost a leg in an accident. He had since been given a post by LCDR to oil the points in the tunnel. On that evening, at 19.00hours, the express train from London entered the tunnel at about the same time as the up-train came from the opposite direction. The express train knocked Mr Hart down and the wheels ran over his body cutting it in half. He was buried in St James Cemetery. On 26 March, Emanuel Sochaczewski (1820-1865), the agent for the Belgium Steam Packet Company who worked for Latham’s of Dover, was killed at Harbour Station. He had been waiting for the London train to meet Sir Cusack Patrick Roney (1810-1868) the Railway Historian and Chairman of the Sevenoaks, Maidstone & Tonbridge Company. As the train pulled into the station, Mr Sochaczewski ran up the platform but was so intent on waving to Roney, he hit a post and fell between the train carriages. He was crushed, died two hours later and was buried in Cowgate Cemetery.

May 1865, and an increasing number of shareholders of LCDR were unhappy. Amongst other things, they called for the agreement with the Kent Coast Railway Company to abandon the last part of the line to Ramsgate. The Kent Coast Railway Company had been floated in September 1862 to build a 28-mile line in conjunction with LCDR from Faversham by Whitstable to Ramsgate but had only reached Margate. There were also calls to either abandon the Dover-Deal line or, if authorisation was given to the Bill that was to be presented to parliament, to sell the authorisation to another company. The Chairman, Lord Harris, did not commit himself to either demands, but did say that three other Bills the directors were considering would be held back. Lord Harris finished the meeting by saying that the Metropolitan Extension would be completed by the end of July 1866.

A meeting was held the following month with Sheffield in the chair, where he told shareholders that the contract had been ratified for the Sevenoaks, Maidstone & Tonbridge Company to build a line between Otford and Maidstone. The agreement, he said, was for LCDR to lease the new section for 999years at £14,500 per year and the line was to be constructed by Peto, Betts and Crampton. In July, with Lord Sondes in the chair a favourable report was presented on the progress of the Metropolitan Extension. However, a Mr Hitchcock criticised the quality of the work thus far on the Metropolitan Extension and asked, ‘what amount of money was in hand to pay debenture interest on the main line and when would the shareholders expect a dividend?’ LCDR’s new company secretary, William E Johnson, responded saying that, ‘if the revenue increased in the next six months as it had done in the past, the balance of profit on the Main Line would be enough to cover all fixed charges on it, and to leave a small surplus but insufficient for a dividend.’

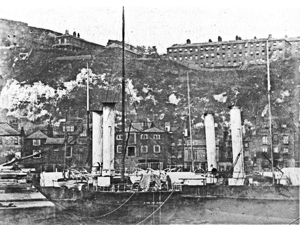

LCDR packet Paddle Steamers Samphire and Maid of Kent at Western Docks with Western Heights barracks on the cliffs behind. Dover Museum

At the shareholders meeting of August 1865 the Chairman Lord Sondes successfully motioned the authorisation to convert ordinary shares into ordinary capital stock in the General Undertaking of the company. On the basis of this 2,400 Dover preference shares appertaining to the cross-Channel packet service were converted to interest bearing shares of £25 each. Called Dover preference arrears stock, redeemable they raised £60,000. At that same meeting, Sondes proposed that ‘The Directors were also authorised to capitalize further arrears of interest on Dover preference capital by the creation and issue of £110,000 additional shares or stock, redeemable and entitled to a dividend not exceeding 5% per annum.’ A number of shareholders objected but Sheffield came to the defence of the proposition, which was seconded by Lord Harris and carried. Peto, in reply to the question concerning the increasing delays and increasing expenditure on the Metropolitan Extension, stated that his firm ‘were proceeding vigorously and that the project was expected to be completed in April 1867.’

At 23.30hours on the night of Wednesday 13 December 1865, the LCDR packet ship Samphire, under Captain John Whitmore Bennett (1828- 1907), was carrying mails and 78 passengers from Dover to Calais. Twenty minutes after leaving the port she was in a mid-Channel collision with American barque Fanny Buck and five passengers lost their lives. In the Admiralty Court the unanimous opinion was that the Samphire was to blame for the accident as the Captain and the crew could see that the Fanny Buck was under sail.

The LCDR Directors six month report dated 26 February 1866 showed that on the capital account, expenditure on the main line had been £4,789,463, on the Metropolitan Extension £6,182,515 with Victoria Stations improvements of £470,718 and City Lines costs £1,125,147. The Metropolitan Extension gross receipts for the half-year was £237,134. On 22 March the Metropolitan Extension, Kennington, Clapham & Brixton Bill was discussed in the House of Lords. The Bill stated that LCDR envisaged raising £2,000,000 by shares and £666,000 by debentures. The railway would have an aggregate length of 9miles 71 chains. On 11 April a nominal amount of £2,207,300 of LCDR ordinary stock, at the time held in deposit for advances, was offered for cash realization at £27 10shillings for each £100 of shares! 5 days later Directors delegated by the Boards of SER and LCDR met to discuss the fusion of the two companies. The chairmen of both companies were at the meeting and therefore it was assumed that the respective companies would accept their recommendations.

On 10 May 1866 at 15.00hours, the city bank Overand, Gurney and Company closed its doors and ceased trading. 11 days later Peto & Betts were suspended by LCDR and the company made other arrangements to enable outstanding works to be completed. SER backed off the proposed amalgamation. On 4 June, in the House of Lords, both Sondes and Harris came under attack from other members. On 30 June LCDR announced the inability to pay the interest due on debentures for the previous six months. This amounted to £76,000, which added to previous non-payments came to £400,000! Proceedings were started in the Court of Chancery by debenture holders but the Court appointed LCDR’s general manager Forbes and secretary Johnson as the receivers. The debenture holders tried to get this overturned but the LCDR Board successfully sought legal protection and, at the same time, an assignment to stop special creditors seizing and appropriating the rolling stock and ships. The special creditors were mainly landowners seeking outstanding payments amounting to £700,000.

After a summer of disquiet on 24 August 1866 a number of LCDR’s debenture and shareholders met and listed a series of resolutions on the issues over which they had concerns. They sent these in a letter to every known LCDR and associated company debenture and shareholder and recommended that an investigative committee should look into their concerns. One week later the Board held a meeting where it was announced that they had just discovered that there had been an over issue of £128,000 of debentures! A debenture/shareholders initiated Committee of Investigation was set up. The members were: Grosvenor Hodgkinson MP (1818-1881) – Chairman, W Edward Hillard – Deputy Chairman, S H Burbury (1831-1911), Thomas A Hankey, William Hartridge, Frederick Heritage, Augustus T Hotham, Cornelius Surgry and G C Taylor. They started work immediately.

At the time, the Board of Directors of LCDR were, Chairman – Lord Sondes, Deputy Chairman – Lord Harris, Sir Robert Walter Carden (1801-1888) – banker and Conservative politician, George Cobb, William Henry Gladstone (1840-1891) – eldest son of the future Prime Minister, Charles Jones Hilton (1809-1866) – cement manufacturer of Court Street, Faversham, Lord Sheffield, and James Rich. The company solicitors were Charles Freshfield and G G Newman. Charles Freshfield (1808-1891) was Dover’s Member of Parliament and was heavily involved in LB&SCR. The LCDR officers were Secretary – W E Johnson and General Manager – James Staats Forbes. The Committee of Investigation published their report on 9 October.

The Committee’s Report started by describing LCDR as a combination of several undertakings each with separate debentures and share capital and each undertaking entirely separate. They were, said the Report:

1. Western Extension – Description included in above, merged with the General Undertakings under the 1861 Act at a perpetual rent of £28,000 per annum.

2. Mid-Kent Cray Line – Description included in above, leased to LCDR by SER from 1 September 1863 for 999years for £361 10shillings per annum.

3. Kent Coast Line – Description included in above, incorporated in separate parts with the agreement that LCDR received half the receipts up to £45,420 and thereafter one quarter of gross receipts. The rent paid by LCDR, £45,000 per annum.

4. Sevenoaks, Maidstone & Tonbridge Line – Description included in above, merged as a General Undertaking the rent paid by LCDR, £11,500 per annum.

5. Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway – Description included in above, leased to LCDR at £7,000 per annum

6. Steamboat Service – Description included in above, added to which, the Service was in debt due to the costs incurred for setting up a shipping company from scratch. However, the Report stated, the Continental Agreement with SER in 1865 had yielded £368,000 gross, divisible between the two companies. The net profit of the Steamboat Service for the year ending 30 June 1866 was £17,434 6shillings 9pence.

The Report then looked at the Metropolitan Extension, saying that it was sanctioned by the Metropolitan Extensions Act 1860 but curtailed and limited under the City Undertaking Act 1864. However, work continued to be carried out financed by the General Undertaking through a number of separate companies set up by directors of LCDR. Examples were given as to how the General Undertaking process worked. Typically, the Crystal Palace and South London Railway Company (CP&SLRC) was given Royal Assent in 1862. Parties connected with LCDR promoted CP&SLRC. One of these was company director Lord Sheffield who acted as CP&SLRC secretary and another was LCDR solicitor, Newman, who was also solicitor to two other General Undertaking companies. For the construction of the line, an arrangement was made through LCDR with Peto & Betts.

The line was to be 6¼miles with 5 stations and estimated to cost £512,000. The authorised capital was £225,000 in debentures paying 6% per annum and £675,000 of 10shilling shares. Peto & Betts agreed to construct the line for a percentage of the debentures and shares. However, the Chatham Company, also an LCDR General Undertaking, refused to allow CP&SLRC to create a junction with their line at Peckham. CP&SLRC’s Chairman, Sir Cusack Roney, turned to LCDR Board for help but they refused to do anything as Lord Sheffield and Newman were abroad. Instead, they declined to sanction the payment of interest on the CP&SLRC debentures saying that the line would never be finished. In reaction, CP&SLRC sought the help of the Government Inspectorate and the line was completed, as a separate undertaking, and opened to traffic in August 1865.

Another of these companies, the Report detailed, was City Lines and their project between Earl Street and Farringdon Street. After an account of its history, they said that the projected line had opened in January 1866 and was in a ‘most unsatisfactory state both financially and with regards to accommodation works.’ The new Victoria Station and the Blackfriars Bridge over the Thames, which also came under City Lines, was treated kinder and it is evident that the Committee were satisfied. Albeit, the Eastern Section of the Metropolitan Extension, they said, was originally to be from Walworth Road Station to CP&SLRC Peckham station and to be built by Peto & Betts. It was intended that eventually the line would be extended to Greenwich with a tunnel under Greenwich Park, through Charlton and terminate at Woolwich. The line between Nunhead and Greenwich was nearly completed in 1864 but nothing had been done between Walworth Road and Peckham or between Greenwich and Woolwich. The issue of debentures and shares was £15,253,597 while expenditure thus far was £16,683,493.

After detailing other aspects of the company, the different railway lines and contracts, the Committee turned to Peto & Betts. They noted that since 1860, Peto & Betts or their nominees had subscribed for the whole share capital of many of the different companies that had been floated through the General Undertaking, on their own account. When asked, Peto & Betts said that in many instances they did this on behalf of LCDR Board. Peto & Betts also alleged that in executing some of the contracts they were undertaken on the understanding that they would be indemnified by LCDR from any loss on the ultimate realisation of the shares, saying ‘That the contracts were executed for the sole purpose of enabling LCDR to raise money on debentures and also, by way of a loan, on the shares and stocks so subscribed.’

The Committee in their Report stated that when Peto had joined the Board as financial advisor in December 1863, a floating debt of £1.25 million, through debentures and shares, was created. This enabled LCDR to issue more debentures and shares to pay for work Peto & Betts were carrying out. The Committee, on investigation, were of the opinion that Peto, or his associates, had taken up this stock at a heavy discount so was able to certify that the majority of it had been subscribed. (This was later proved to be correct). On 11 April 1866, £2,207,300 of LCDR ordinary stock was dumped on the market. Peto & Betts told the Committee that they did this on behalf of LCDR ‘but’, the Report stated, ‘the company only received £38,000.’ The Report finishes this section by saying that ‘without expressing the opinion that proper care had not been taken to protect the interests of the company with reference to contracts of work. Not only was no competition invited but the necessary precautions do not appear to have been taken in fixing the prices to be paid.’

The Board of Directors of LCDR also came in for fierce criticism. The Committee’s Report reminded them that legislation limited borrowing by the use of debentures to one-third of the amount raised by shares. Further, ‘there is a bona fide liability on the part of shareholders to pay the remaining half of such share capital. Various Acts forbid these powers to be evaded until the whole of the capital for which the shares had been subscribe or taken and one-half paid up.’ Finally, every stage required to be approved by a Justice of the Peace so that debenture creditors would be protected. The accounts, the Committee reported, showed this legislation had been systematically evaded. Several issues of debentures exceeded the amount LCDR received from the sale of shares. In the case of the Eastern Section the whole of the share capital of £1,070,000 was subscribed for by Peto & Betts or their nominees and the only capital actually raised was by debentures. There was also an over issue of debentures on City Lines and many of the other Metropolitan Extension companies.

The Report particularly cites the nominees listed for a Metropolitan Extension company in August 1864 taken from LCDR’s Allotment Book. They were Edward Ladd Betts, Charles Ladd Christian, Thomas Crampton, John Hervey, Charles Lowinger (1823-1880), Henry Miller, Sir Samuel Peto, Sir Cusack Roney, Frederick Henry Trevithick (1816-1902) and Thomas White. The amount the nominees were credited as paying was £750,000. In fact, no money was actually paid by them, said the Committee, and when interviewed, most were unaware that their names had been used. Albeit, in the same month debentures for the said company were issued to Peto and Betts for £390,000 and in the months that followed debentures to the public were issued for £110,000 giving the full Parliamentary limit of £500,000 for debentures. At the time, the Commission added, it stated in LCDR’s records that a number of shareholders had written, expressing concern about the flotation but the Board made it clear the share money was accountable.

In the final section of their Report, the Committee looked at land dealings and made a number of recommendations but in essence, lumped these creditors with the debenture and shareholders. The Committee made it clear that saving the future of LCDR was uppermost in their minds but gave an order of priority of the creditors to be paid, starting with landowners, followed by the different debenture holders and then the different types of share holdings. Noting that the debenture and share holdings were in the hands of the Court of Chancery and that they make take a different view. Thus, the immediate business was the completion and improving of existing lines – £338,526, rolling stock and machinery – £28,275, new lines, authorised work and work applied for – £877,858, which altogether came to £1,244,659. Saying that, ‘the whole organisation will be a great jeopardy until measures are promptly taken to raise capital to pay off the floating debts and thus enable debenture holders and share holders to receive the net proceeds on the different lines as they accrue.’

Summary of the Bill prepared by the Directors of London, Chatham and Dover Railway – The Times 19 December 1866

Although LCDR’s Board of Directors took notice of the Committee’s Report, on 17 November 1866 they presented parliament with a dictum on how they believed LCDR could be extricated from its problems. In this they asked to be given the power to create £1,500,000 stock to take preference over all existing shares and debentures. With this they would clear all liabilities and complete, with the exception of the Walworth and Peckham branch, the Metropolitan Extension. Second, the authority to issue £5,203,500 debentures, bearing a perpetual 4% dividend, the proceeds of which was to be used to redeem all existing debentures. Third, amalgamation of the various sections of the General Undertakings and lastly, all suits against LCDR to be frozen for twelve months and on the part of the debenture holders for five years. This proposition was agreed under the LCDR Arrangement Act of 1867.

In the months that followed LCDR was restructured replacing the Board of Directors and the company solicitors. A number of Acts were passed that tightened company law and the LCDR Arbitration Act 1869, was passed. This was to deal with LCDR claimants and Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) – Prime Minister from 1895-1902 and Hugh McCalmont Cairns, 1st Earl Cairns (1819-1885) – Lord Chancellor in 1868 and again 1874-1880, were appointed as the Arbitrators. Their judgement was that from 30 June 1870 the various companies that made up LCDR, including those floated under General Undertakings, were to be consolidated into one company retaining the name of the London, Chatham & Dover Railway Company (LCDR). From 18 August 1870 and within three years, LCDR were to sell and convert into money all superfluous lands and deposit the net proceeds into the London & Westminster Bank LCDR Arbitration Land Account. And LCDR were to redeem all debentures issued by the previous Board of Directors under the LCDR 1867 Arrangement Act. These had raised £30,250 and LCDR was to pay all outstanding interest.

The way forward to save the company, the two Arbitrators said, was for LCDR to issue £5,000,000 in debentures at 4½% per annum and to be called the LCDR Arbitration Debenture Stock. They were also to issue preference shares amounting to £4,384,289 with a preferential dividend of 4½% per annum and referred to as the LCDR Arbitration Preference Stock and ordinary stock to the amount of £7,743,405 to rank after the preference stock and to be called the LCDR Arbitration Ordinary Stock. LCDR, as a company, could only issue up to £5,475 ordinary stock as deemed by the 1866 Railway Companies’ Securities!

Liabilities were put into 15 sequential Schedules and monies raised, after meeting the requirements of saving the railway service, was to clear each Schedule in turn. The Arbitrators listed, within each Schedule, the full liabilities and costs. The second part of the Arbitrators Report concerned the voting rights of the holders of the Arbitration stock. Again they emphasised that they were mindful that the practical role of LCDR, that of providing a railway service was paramount and that liquidating to pay previous creditors could have disastrous consequences on both company and the services. With this in mind, they stated, the Arbitration debenture holders were to be given one vote for every £100 they held in LCDR stocks while shareholders would have 1 vote for every £300 of stocks they held.

LCDR survived but most of the original investors lost their money. Legal action was brought against the previous Directors, but both Lords Sondes and Harris had died before conclusions were reached. Peto & Betts company was dissolved and both men were declared bankrupt. An attempt was made by the new Board of Directors of LCDR to sue, but were persuaded that it would be fruitless.

- Presented: 09 December 2015