‘Once the leader of Dover, died in London on 2 January 1900 at the ripe old age of 81.

Kearsney Manor c1970s, the country home of Joseph Churchward in the years before he died.

We regret to record the death of Mr Joseph Churchward which occurred at his residence, Gilstone Road, Kensington, on Tuesday evening at the age of 81. Mr Churchward more than a year ago finally retired from public life giving up his office as Chairman of Dover Rural District Council, and a few weeks ago he left his residence at Kearsney and moved to Gilston Road where he died.’ So began Joseph Churchward’s obituary in the Dover Express. Churchward was a newspaperman with Machiavellian principles who came to Dover to run the newly privatised packet service in 1854.

Joseph George Churchward was born in Devonport on 22 December 1818, and used his knowledge of the nautical aspects of his native town when he moved, as a youth, to London. There he trained as a journalist and quickly rose to become the naval editor of the United Service Gazette and the Nautical Standard. About 1842, Churchward joined the staff of the politically Conservative, London Morning Herald, as the naval editor. At the time, the newspaper’s editor was Dr Stanley Lees Giffard (1788-1858), the father of Harding Gifford, 1st Earl of Halsbury (1823-1921), later Lord Chancellor. An ardent Conservative, Churchward took on the role as agent for Charles John Mare in the General Election of July 1852.

Mare was an engineer and shipbuilder who owned and ran the large Orchard Yard at Blackwall on the Thames. Those were the days before the introduction of the ballot box and on a show of hands Mare was returned as one of the two representatives for Plymouth. The other MP was Liberal lawyer Robert Collier, 1st Baron Monkswell (1817-1886). However, before the celebrations were over, the losing candidates launched a petition stating that some voters for Mare had been bribed with promises of government employment or situations. Churchward was named as the culprit when 29 of those who had voted for Mare were subsequently given government posts! Mare was unseated and the succeeding election was won by Conservative lawyer Sir Roundell Palmer (1812-1895), later the first Lord Selborne.

During his career as a naval journalist, Churchward had created a network of close contacts in the Admiralty and he was well versed with the details of the Dover Packet Service. The story, Packet Service I to 1854, gives the details of its inception and notes that due to the proximity of Dover to the Continental mainland the port was a favourite Passage crossing of the Channel from the earliest times. Following the invasion of England by William I (1066-1087) in 1066, the Domesday Book of 1086 recorded that King’s messengers, riding on horseback, paid 2pence in summer and 3pence in winter, for their passage across the Channel to Wissant, in the northern France. In 1227, Henry III (1216-1272) conferred on Dover the monopoly of the cross-Channel traffic to Wissant but from 1381, by Royal proclamation, the passage was changed from Wissant to the newly formed port of Calais. By the early seventeenth century Dover still retained the major crossing between England and France and the passage ships that specialised in taking pacquettes, that is Royal messages etc., became known as Packet ships. Built in Dover, these ships were renowned for being efficient and fast.

The 1657 Postage of England, Scotland and Ireland Settling Act, enacted the position of Postmaster General. Following the Restoration in 1660, the Post Office packet service was ‘farmed’ by wealthy individuals and Dover’s first post office was established in 1673 in the Customs House on Customs House Pier. Four years later it had been moved to Strond Street and remained in the Pier District until 1893 when it was moved into purpose built premises on King Street. In the 18th century the farming of mail was replaced by individual contracts under license by the Post Office By the time of the French Revolution in 1789, there were five Post Office packet licences for Dover ships with thirty such vessels sailing between Dover and the Continent.

South Prospect of Dover c 1739 showing a variety of ships in the Bay with the Castle beyond. Dover Harbour Board

Following the start of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), the base for the Channel packets moved to Harwich but within ten years, a packet service was operating out of Dover and administered by the Admiralty. On 10 October 1815, the packet service was officially resumed with ships going to Calais and Ostend and in 1821, the service was taken over by the Post Office. This was the age of steam ships but they were proving costly to run such that by 1836, the Post Office was making, on average, a loss of £38,739 a year. A number of private concerns made offers to take over the service but instead, in December 1836, the national packet service was transferred to the Admiralty with the Post Office regulating the times of departure.

On Tuesday 6 February 1844, the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) opened their railway line to Dover but two years before, Joseph Baxendale (1785-1872), the Chairman of SER, had purchased the silted up Folkestone Harbour and after undertaking vast and expensive improvement, made Folkestone SER’s crossing port to the Continent.

From that time, SER had regularly applied to the Admiralty for the Channel mail packet contract but had been consistently refused and therefore turned their attention to petitioning Parliament on the subject. In 1850, the Railway Company submitted an offer to carry the mails across the Channel for £9,825 and a parliamentary committee was set up to investigate. They looked into the possibility of putting the Dover and Calais packet service out to tender but were informed that, after allowing for the receipts from passengers, the carriage of the mails between the two ports cost £6,244 per annum. As this was significantly lower than the sum SER had offered the Committee reported that putting the service to tender would involve increased expenditure, so no action was then taken.

Nonetheless, SER did not give up and instead used the Great Exhibition, held in London in 1851, to illustrate the efficiency of their service. Both the SER and the Admiralty, made substantial profits from the carriage of passengers during the time of the Exhibition. At that time, the Admiralty packet ships out of Dover were the Dover, Garland, Onyx, Princess Alice, Violet, Vivid, and the Widgeon. However, in 1852, the Violet had to be taken to the naval dockyard at Woolwich, on the Thames, following damage to her bowsprit and bow. Following repairs, Captain Baldock, the inspector of the Dover Mail Packets, checked her out and she returned to Dover. Nonetheless, SER with the help of national newspapers journalists including Churchward, used the incident to put pressure on parliamentary representatives for the service to be put out to tender. SER suggested that such contracts would give an annual saving to the government of £10,000 and in September 1852 Churchward made a tentative proposal to run such a service himself.

Following the General Election of 1852, a parliamentary coalition was formed between the Whigs (later Liberals) and the Conservatives. The Chancellor of the Exchequer (1852-1855) was the Whig William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898). War had broken out in the Crimea and it looked as if Britain would become involved – and was from March 1854 to 1856. Cash strapped, the government set up a parliamentary committee in 1853, to look again at the proposition of putting the mail contract out to tender. That summer they published their report in which it was concluded, ‘the service between Dover, Calais and Ostend appears to have been satisfactorily performed as regards both mails and passengers, but as a line on which there is so great a passenger traffic may be expected to be self-supporting. As the receipts from passengers, fares and freight parcels do not cover the cost and expenses of the packets, we recommend that tenders be publicly invited. In order to ascertain whether a contract may not be formed by which the service may be done with greater economy, and under stipulations that would prevent any diminution of punctuality and efficiency.’

The Comptroller of Victualling and Transport Services, T Grant, prepared a draft of conditions of tenders for both the mail services between Dover and Calais and Dover and Ostend and this was approved in December 1853. With the closing date of 26 January 1854, advertisements were placed in the newspapers and tenders invited. By that time, three companies had submitted offers, SER for £16,520 annually to serve Calais only but with eight ships. The second, North of Europe Steam Navigation Company with a tender for £19,750 annually to run six ships to both French and Belgium ports and the third was a Henry Jenkins & Co to serve both routes for £15,500 annually with only one ship but stated that there were five more on order.

Henry Jenkins & Co was in fact a syndicate headed by Messrs Jenkin and Churchward. Although a formal agreement had not been drawn up, there were four members – Joseph George Churchward, Captain Henry Jenkins, Edward Baldwin and Timothy Harrington. Henry Jenkins was the Captain of the Morning Herald‘s despatch boat Ondine (II) and although Jenkins name was the syndicate’s title, he was very much a junior partner to Churchward.

The original Ondine was an iron paddle steamer built in 1845 for Dover ship owners, Messrs Bushell and worked the Dover-Boulogne passage with the licence to carry the Indian mail. When that packet service ceased from Dover the Ondine was sold to Edward Baldwin the proprietor of the London Morning Herald. He subsequently sold her to the Admiralty who renamed her Undine, occasionally coming to Dover on a temporary basis. She was replaced in Baldwin’s fleet by Ondine II and made regular Channel crossings.

– Edward Baldwin acquired the ownership of the Morning Herald in 1843 and offered to supply the capital to finance the undertaking if Churchward’s bid was successful.

– Timothy Harrington was the Ondine (II)‘s engineer and so had the technological knowledge that would be needed.

All were unqualified to run a high pressured, high prestige packet service across one of the most hazardous stretches of water in the World. Further, they were woefully under financed and resourced with only the Ondine (II), yet, as a syndicate, they had deliberately put in the low and unrealistic tender that had been accepted. Possibly, for this reason, Baldwin dropped out of the syndicate but he did agree to sell Churchward the Ondine (II) if they were successful. Churchward’s old friend Charles Mare took Baldwin’s place, as a silent partner, within the syndicate.

On 4 February 1854, Ralph Bernal Osborne (1808-1882), Liberal MP for Middlesex and Secretary to the Admiralty 1853–1858, wrote to Henry Jenkins & Co, accepting their tender of £15,500. The contract required ‘the carrying mails at not less than 13-knots an hour and by no less than six steam vessels, each of at least 100 tons’ register and manned by competent officers. A ship was to leave from Dover to Calais and another from Calais to Dover every weekday and for Ostend a ship had to leave Dover alternate weekdays and another to leave from Ostend to Dover every alternate weekday.’ The contract was to continue until 1 October 1858 but the syndicate still only had one ship and she was just 100-tons!

Churchward suggested to the Admiralty that as they were no longer running the Dover packet service he would relieve them of the ships! The Admiralty were not taken in but did agree to sell three of their former packet ships, the Onyx, Undine and Violet for £13,000, payable by quarterly instalments. It was also agreed that Churchward would lease two more ships for a couple of weeks, the Vivid and Princess Alice. The contract was underwritten and signed on 2 April 1854 by Mare who also agreed to supply two more ships.

Thus, at the time Churchward took over the Dover packet service his syndicate owned:

Ondine (II) Iron Paddle Steamer built and engined by Miller, Ravenhill & Co. in 1847 for Edward Baldwin and was 101.1 -tons

Onyx an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall and engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich. Her tonnage was 294 gross and bought by Churchward as part of the Mare underwritten deal. Having new boilers fitted she did not come into service until May 1854.

Undine an iron paddle steamer built and engined in 1845 by Miller, Ravenhill & Co of Blackwall, and 86 burthen. Registered as Ondine when Edward Baldwin owned her and although small, had proved to be fast. It was for this reason that the Admiralty had bought her in February 1847 and allowed her to be used on the packet service. Churchward renamed her the Dover (II).

Violet an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and tonnage 295 gross. This ship was used, in 1852, by SER and Churchward to show that the Admiralty wasted money.

The two ships on a lease were the Vivid, a wooden paddle steamer of 352 ¾ burthen and the Princess Alice, an iron paddle steamer 110.1 burthen.

For premises, the Dover Harbour Commissioners offered the lease of a 300-foot frontage of the Wellington Dock but Churchward could not afford the amount asked. With considerable audacity, Churchward turned to the Admiralty and again reminded them that they were no longer running the packets service and offered, as a caretaker, to look after their packet yard and offices between what would become Granville Dock and Snargate Street. Much to Churchward’s delight, the Admiralty agreed but as he had to admit that he would be using the premises they came to an arrangement he could afford.

Although Churchward had written a great deal about the Packet industry, he was still a novice as to how the transportation of mails worked. He quickly learnt that the ship’s captain would assign one of his officers to prepare the stowage plans of the expected mails. The officer would ensure that the consignments were kept dry, were equally spread throughout the ship and could be quickly unloaded when the ship arrived at the designated port. The packages were in bags and were stowed at approximately thirteen bags to the ton in a space of 40-cubic feet. Government confidential mail was stored in the ships safe along with ‘bullion‘ packages from private firms and individuals. Bullion packages contained gold, silver or/and coins and were sealed and weighed in boxes by the sender before being transported to the railway station. A ‘waybill’ gave the weight of the sealed box but not the contents where it came from and the destination. The weight of the box was checked against the waybill at the railway receiving station before signing acceptance. The box was again weighed and checked against the waybill, before being carried on board the packet ship and again after unloading at the destination port prior to being transported to its final destination where the exercise was repeated. (See the Great Bullion Robbery story part I).

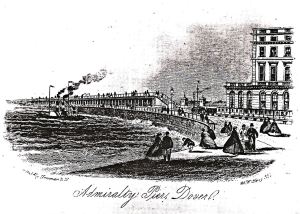

Fairbairn hand crank crane 1868 Wellington Dock similar to one mounted on Admiralty Pier used for loading mail on and off packet ships. Alan Sencicle 2009

The bags of ordinary mail, on arrival in Dover, were examined by post office officials and numbered. Again the waybill system was used showing where the bag came from and it’s destination. The number of packages the bag contained and the overall weight of the bag were all noted on the waybill. The loading of the mail always took time and took precedence over passengers. If the mail train was late or there was a particularly large consignment of mail, then the ship would leave late and on some occasions passengers’ baggage had to travel on a separate ship to make room for the mail. The mailbags, in those days were hoisted onto and off the ship by crane, similar to the Fairbairn hand crank crane that can be seen at the south side of the Wellington Dock, the crane being mounted on Admiralty Pier. Throughout the operation, a cross-check was maintained to ensure that all the mail on the waybill were loaded onto the ship. Once the ship was loaded, an officer from the ship along with the guard of the train checked the train to ensure that no item had been left behind. Once the mail was stowed and the ship had sailed, those involved in the loading of the mail returned to normal duties. On arrival at the port of destination, following unloading, each bag was checked against the waybill. Once those on shore were happy that the packages and the waybill correlated, the loading of the ship with mail going in the opposite direction began. On reaching Dover, the waybills were recorded and filed.

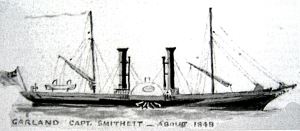

On 15 April, after 40 years service and as Commodore of the Admiralty Fleet from 1837, Luke Smithett (1800-1871) retired. On that day, after conveying the Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (1859-1904) and General Lord Raglan (1788-1855) to Calais, he took the Vivid to Woolwich. There she was refitted for general duties in the Royal Navy and in her stead the Garland was offered to Churchward. The Garland was a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and tonnage of 295 gross. She had previously worked the Dover packet service and Churchward had little alternative but to buy her outright costing him £4,800, which he could ill afford.

The Princess Alice returned to the Admiralty and for the first summer of his operations Churchward was a ship short but luckily, Harrington had ensured that none of the fleet had to be taken out of service. At the Admiralty packet yard Harrington, when Churchward had the money, started to build up stores and a crew of specialists to ensure that as much maintenance of the ships as possible could take place there.

However, on the 23 August Churchward rented the Princess Alice for a couple of weeks, while he leased the Dover, Onyx and Violet, under the command of Luke Smithett, to the French Government to take French troops to the Crimean War. The amount he earned from the deal helped Churchward’s severely limited finances and it was hoped that at least one of the two ships being built by Mare would come on station before the year was out. However, the Crimean War meant that there was a shortage of labour and scarcity of materials and in consequence the ships did not arrive. Thus, the Princess Alice remained in Dover until 14 February 1855 at considerable cost to Churchward.

The three ships he loaned to the French actually returned by the weekend of Saturday 18 November 1854, but heavy weather meant that the mail packet did not leave Calais until 08.00hrs. Subsequently the mail was late in arriving in London and this was given national news coverage by those who felt that the contract should have been given to SER. Over that weekend the weather, particularly on the Continent side of the Channel, deteriorated such that on the Sunday the packet ships did not leave either Calais or Ostend. On the Monday morning the national papers were particularly nasty thus the Onyx was about to leave Dover in the most atrocious weather. There were 70 passengers on board, when the heavy swell snapped her hawsers and drove the ship so hard against the Admiralty Pier that her paddle box spring beam was damaged. The mail and passengers were transferred to another packet ship that managed to make the crossing. As Harrington did not have the parts, equipment or expertise the Onyx was towed to Mare’s shipyard. There she was rebuilt and renamed Vivid II before returning to Dover.

In order to make the business profitable it was imperative for Churchward to win the Belgium contract for carrying mails from Ostend to Dover and ideally to give him the monopoly he needed to win the French contract. In order to win the Belgium contract, on 30 November 1854, Churchward set up the Dover Royal Mail Packet Company to run the Dover packet service in line with the Admiralty contract. The syndicate ceased to exist. Instead, Churchward became the General Manager in charge locally and Mare the Managing Director of the company as a whole. Jenkins and Harrington became highly paid senior employees, with Jenkins as Captain of the Ondine – with which he was happy – and Harrington the superintendent of the marine engineering department at the former Admiralty Packet Yard. Harrington’s salary was £450 per year plus 10% of profits made. Luke Smithett was appointed Commodore of the Dover Royal Mail Packet Company fleet. Shortly after, Churchward won the Belgium contract which was particularly lucrative as he did not require any more ships, once the new ones arrived.

However, towards the end of 1854 the great sluices at Calais harbour collapsed making it impossible for Churchward’s packets to use the harbour. Smithett handled to public relations, apologising for the delays in the service and ensuring that a packet ship would run both ways everyday. In the meantime the Calais harbour authorities were constantly pressured by Churchward and made the necessary repairs. Much to the annoyance of the Calais officials, the French authorities were impressed with Churchward’s persistence and in January 1855, he secured the French contract as the sole carrier for inward-bound Calais-Dover mails.

The contract was for fifteen years but there were stipulations, for instance, ships carrying the day mails from Calais had to run under the French flag and be French manned and owned. To meet this criterion Churchward employed both French and British crews, so when the English officials came aboard, he would say that his crew were predominantly English and when in France, he would say that his crew was predominantly French! Again the French authorities were impressed, this time with the pretence and paid Churchward an extra £7,000! However, the caveat was that only Churchward’s new ships were to be used for the French contract and that the older ships were to be used for the Belgium mails. To get round the latter stipulation, Churchward renamed the Garland, L’Alliance placed her under the French flag, gave her a predominant French crew and put her on the mid-day run to Calais and back.

With the long-term contract from the French, before the month was out, Churchward wrote to the Admiralty suggesting that they extend his contract to 10 years! He justified the extension by saying that as his existing fleet were aged and were costing a great deal in upkeep but were not worth replacing unless his contract was extended. The Admiralty declined noting that the two promised ships at the time of the original contract, were about to be launched. They were the Empress and the Queen, and following trials on the Thames, arrived in Dover in February 1855 within a fortnight of each other. They were built and paid for by Mare and were 123.5 burthan with 2 x 50 horsepower engines made by Ravenhill, Salk & Co. Due to Churchward’s necessity to retain the façade demanded by both the British and French terms of contracts, the Queen was sometimes referred to as the La Reine. From the moment they arrived in Dover, both ships were hailed for having ‘splendid lines’ and the internal passenger furnishings were luxurious.

Luke Smithett captained the Empress and the Queen was under the superintendence of Captain Moore. One of the ships left Dover for Calais every day at 14.00hrs or on the arrival of the 11.30hrs train from London if it was delayed. The ship returned at 22.00hrs from Calais, on arrival of the train from Paris. The first class fare was 9-shillings and second-class 7-shillings. The address given for Dover Royal Mail Packet Company was 56 Lombard Street, London.

Vivid and the landing of King Victor Emmanuel of Sardinia on 30 November 1855. Illustrated London News

In April 1855 Emperor Napoleon III (1852–70) and Empress Eugénie returned to France after a state visit to Britain. They travelled on the new packet Empress, but the crossing was somewhat rough and as Calais harbour was still proving to be a problem the ship berthed in Boulogne having taken 2½hours. During the crossing, the Emperor conferred upon Smithett the Legion of Honour and the media coverage was considerable and favourable to Churchward’s packet service. In March 1855 the alliance between Sardinia and England was ratified and on 30 November King Victor Emmanuel of Sardinia (1849-1861) arrived in Dover on the Vivid. He and his retinue stayed the night in the Cambridge apartments at the Ship Hotel on Custom House Quay where John Birmingham was the mine host.

By May 1855, the Calais harbour problems had been dealt with and Churchward was advertising the packet service to France. However, on 4 May 1855 the Dover hit the west pier head at Ostend during heavy weather. The passengers, mail and crew were rescued but for Churchward it was financial blow as the Dover was under-insured. Churchward wrote to the Admiralty asking for an increase in the annual contract payment and an extension of the contract but received short shift. He again wrote and persistence paid off, for on 5 July the newly appointed permanent secretary, barrister and Liberal Thomas Phinn (1814-1866), agreed to extend Churchward’s contract until 20 June 1863. He also allowed Churchward to use the former Admiralty packet premises rent-free but the annual Admiralty packet contract payment was reduced to £13,500.

Much to Churchward’s shock Mare was declared bankrupt in October 1855. His unsecured debts were given as £160,000 and total liabilities £40,000. The bankruptcy court heard that Mare’s shipyard order books were full and that 20 Government iron mortar vessels of 100 tons and worth £2,200 each were under construction of which 6 were ready for delivery. Six gunboats had recently been launched while others were still under construction along with despatch boats. Besides government orders, the shipyard were building a number of other ships for private concerns but due to the Crimean War there was a shortage of materials and men, albeit Mare’s wage bill came to £3,500 weekly.

With Mare’s bankruptcy, Churchward could not afford to replace his entire fleet with new ships and so repairing the existing fleet was given priority. Harrington and his men were undertaking the day-to-day maintenance and repairs but major repairs had been undertaken by Mare’s shipyard at a reduced cost as Churchward could not afford competitive rates for such repairs. Harrington had nagged to upgrade and extend the facilities and expertise at the Admiralty packet yard, as this had become the cheapest option. Churchward agreed.

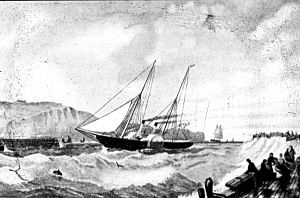

The captains of his fleet were also doing their best to provide a successful service. Typically, an equinox gale on 28 September 1856 made it difficult for the packets to get alongside Admiralty Pier and by that evening, the weather was so bad that it was not expected that any of the packet ships would return to Dover. However, at about 22.00hrs the Ondine from Calais, with Royal and Imperial mails and 50 passengers on board, with her canvas set, came into Dover Bay at a tremendous rate. At that time, steamship engines were unreliable and sails were carried for use in such weather. The flag was up to show that it was safe to enter the harbour and hundreds of people came to Admiralty Pier to watch. The little ship made it to the harbour entrance but the entrance was blocked with debris from the Admiralty Pier works damaged by the gale. The Ondine bore away, ‘in a most stately fashion,’ and eventually moored in Ramsgate where the mail and passengers were disembarked.

Technological innovations had given rise to the birth of the modern communication industry and on Wednesday 28 August 1850, an experimental channel submarine telegraph cable was laid between Dover and France. The following year, on 24 September 1851, the first permanent cable was laid and Churchward was quick to recognise the importance of the telegraph especially if crossings were delayed due to adverse weather conditions. However, submarine telegraph cables were vulnerable and on the night of Monday 5 January 1857 during a storm force 10, a 700-ton heavily laden ship lost her anchor in the Downs. Driven by wind and tide she was in danger of colliding with the schooner Spirit of the Age, whose crew let the anchor play out releasing 40-fathoms of chain. Then the ship suddenly came to a halt.

In Ostend that night, Captain Edward Lyne was in charge of the 300-ton Channel packet, Violet and tried to communicate with Churchward. Lyne, an experienced captain, wanted to delay the crossing due to ‘a storm of wind from the north-east and snow making visibility poor,’ and wrote the message down for the telegrapher. The telegrapher tried to send it but the line was dead and so the Captain asked the clerk to amend the message to say that the Violet would make the crossing but was likely to be delayed. This the telegrapher wrote down and said that he would send it as soon as possible.

The Violet cast off at 20.30hours with a crew of 17, a mail guard and one passenger – other passengers, who were due to travel that night changed their minds. Meanwhile, the Spirit of the Age, as quickly as she had come to a halt suddenly swung round and was careering forward at great speed when, for the second time, she came to an abrupt halt. She eventually broke away and came to grief on the Goodwins, by which time her crew had taken to the lifeboats.

The Violet had come into service at Dover in February 1846 and it was a minor accident in 1852, that was used by SER and Churchward to put pressure on Parliamentary representatives for the Packet contract to be put out to tender. On New Year’s Eve 1852/3, Joseph Wright, a stoker, had an argument with another seaman, Richard Sharpe, on the Violet while she was in Ostend harbour. This led to a struggle and although no witnesses actually saw any blows being struck, Wright did end up on the floor and immediately complained that the back of his head hurt. Sharpe apologised and the two men shook hands and had a cup of coffee. Then Wright was sick and went to lie down and three hours later, he was talking incoherently. On examination by a doctor he was admitted into Ostend hospital where he died that night.

An inquest was held at the Shakespeare pub, Hawksbury Street in Dover’s Pier District, and by a unanimous decision the foreman of the jury, William Hopley, announced a verdict of ‘homicide’ by Richard Sharpe. This took the Coroner, George Thompson, by surprise and when he interviewed the jury, he found that they were unclear as to what homicide meant. Eventually, the verdict was revised to manslaughter and Sharpe was sent for trial at Maidstone. On 7 March 1853 in front of Sir Edward Hall Alderson, the hon. Sir John Taylor Coleridge, and Francis Colville Hyde – the Sheriff of Kent, Richard Sharpe was acquitted.

The Violet was due into Dover by 22.00hrs on 5 January 1857, and the mail train was held for her arrival. By midnight she still had not arrived and the gale was given as the reason for the delay. Churchward tried several times to contact Ostend by telegraph but the line was dead. By 04.00hrs, concern was being felt and the mail train was allowed to leave. By 07.00hrs, when the Violet had still not arrived concern gave way to agitation and folk were coming to the harbour to hear of news. Churchward and Smithett tried to keep the assembled crowd calm by saying that Captain Lyne was an experienced mariner and had decided to stay in Ostend on account of the weather but due to the telegraph still being out of order, there was no way of checking.

Both Churchward and Smithett knew that Lyne would have left Ostend as soon as possible and so telegraphed harbours on the Kent coast for news. On the Tuesday afternoon, word reached them that three bodies had been seen off Ramsgate and fears of a tragedy rippled throughout the town. By Wednesday morning the harbour was crowded with folk waiting for news when the news came that the Violet had left Ostend on the Monday evening. Then Churchward received a telegraph saying that portions of cabin doors, the chain box and other articles had been found on the on the outer edge of the southern spit of the treacherous Goodwin Sands. Captain Smithett immediately left Dover on the Empress for Ramsgate and the Goodwins.

Mapp of the Downes December 1736 by Charles Labelye. Violet was wrecked on south of the Gull Beacon on the Goodwins 5-6 January 1857

On arrival at Ramsgate, Smithett was told that the three bodies had been picked up and brought ashore. They had been found lashed to a life buoy not far from a wreck, believed to be the Violet, which lay on the sand southward of the beacon. Smithett went out to see it and wrote in his report that, ‘From the position of the vessel’s head, I am of the opinion that, having as they thought, run their distance, and catching sight of the Gull Light through the terrific snowstorm, the two lights were mistaken for the South Foreland. I find this mistake is frequently occurring. The vessel sits upright on the sand, funnel gone; decks, bulkhead, cabin doors &c to be seen floating away. Some luggers, either from this place or Deal, were seen out near her at low water.’

The bodies were identified by William Kay, second mate of the Empress. The men were stokers Nathaniel Harmer, William Patrick and Samuel Sharp. The inquest was held in Ramsgate where it was presumed that their deaths resulted from cold, and not from drowning – a supposition that was supported by the appearance of the corpses, according to Smithett, as they looked more like living than dead men. The jury returned a verdict of ‘Found drowned.’

That afternoon Smithett brought the three stokers from the Violet back to Dover and having recovered the mail that the Violet had been carrying, arranged for it to be landed at Folkestone. Eighteen officers and crew were lost, they were: Captain Edmund Lyne; Chief Officer James Paul, Second Officer Henry Pullman, Engineer George Dilks, Mail Officer Mortleman, Carpenter Alexander Smart, Boatswain George Freeman, Leading Stoker Nathaniel Harmer, Stoker William Patrick, Stoker Samuel Sharp, Steward Stephen Penny, Cabin Boy Penny, Ship’s Boy William Crofts, Seamen Henry Fox, James Harber, Samuel Laslett, John Shillatoe and James White.

In Dover, concern and sympathy turned to the bereaved, as it was certain that the 16 widows and 42 children would all be plunged into destitution. A subscription was hastily organised and a gentleman walked into Churchward’s office leaving a £5 note with the message, ‘as a contribution from an intended passenger on the Violet.‘ By that time the Mayor, James Worsfold, a retired naval officer, had organised an official fund raising with Luke Smithett as one of the Trustees.

Francis Cockburn and the Violet disaster letter to Captain Smithett published in all the national and many international newspapers. Times 14 January 1857

Lieutenant General Francis Cockburn (1780-1867) of East Cliff wrote to Smithett suggesting that a letter to the national newspapers would be appropriate in raising money for the poor widows and orphans saying that, ‘these unfortunates, it does appear to me, are fully entitled to public relief as those in the army and navy who are killed in action or died in hospital in the Crimea.’ He went on to say, ‘The wreck of the Violet is quite distinct from the general class of wrecks, inasmuch as it was entirely caused by the zealous and gallant determination to fulfil a public duty, and I do think if so stated in the London papers a large subscription would be made there. It was the desire of duty to fulfil the contract made with the country that led to this sad result.’

Smithett did as was suggested sending a copy of Cockburn’s letter which was published in national and international newspapers. Donations came in from far and wide and included a large contibution from Frederick William IV of Prussia (1840-1861). The fund raising proved so successful that monthly payments were regularly made to eleven of the widows at the Dover Sailors’ Home for many years after as well as making improvements to the establishment. An inventory of the crew showed that Samuel Sharpe was a relative of Richard Sharpe, who was cleared of causing the death of Joseph Wright on New Years Eve 1852. The reason the telegraph was not working that night was due to the Spirit of the Age anchor fouling both the Ostend and Calais telegraph lines. It took a month to make repairs and cost £1,627.

Part III of the Packet Service – Churchward, the Packet Yard on Snargate Street follows.

- Presented: 22 July 2015