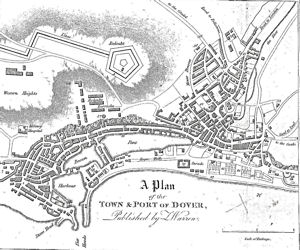

Dover’s ship building industry can be traced back to the Bronze Age and from Saxon times to the Middle Ages, Dover, as part of the Cinque Ports, provided the ships that effectively was the English Navy, (see Shipbuilding part I). During the 18th century, as can be seen in Shipbuilding part II, Dover’s ships were known as the pride of Europe and thus, as seen in Shipbuilding part III played an important role in the years leading up to and including the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815). Part IV of this story begins at the end of the Napoleonic Wars and takes the reader to the present day.

Late 18th century poster showing the various types of ships that were being built at the time, many of which were built on Dover’s beaches. Welcome Foundation Wikimedia.

Following the Napoleonic Wars the Admiralty sold off many of their ships including most of those built in Dover. These included the Tisiphone, sold at Deptford in January 1816 for £1,000; Harpy was sold to a Mr Kilsby for £710; the 385ton Moselle was sold, the 290ton Gannet purchased by the Navy while being built by the King shipyard sold for £770 and the 384ton Eclipse, the last ship built by the King shipyard, sold for £1,400. The 284ton Nightingale sold for £810. G.F Young was particularly interested in Dover built ships from the King shipyard. In February 1819 he bought the Scorpion for £1,100 and a month later the Forester from the Admiralty. In 1815 the Cherub was recommissioned to the Royal Navy’s African station but was sold to a Mr Holmes for £940 in January 1820. Phoebe, the Fector ship that was her ally at Valpariso, Chile, in March 1814, was returned to Dover.

The selling of redundant ships by the Admiralty flooded the market and although Dover shipbuilders found work doing repairs and refitting, new orders were hard to come by. That is with the exception of hoys, small single masted cargo ships used for carrying flour from Dover’s cornmills to London. Shipyards closed and associated tradesmen found work difficult to come by. Further, approximately a quarter of a million soldiers and sailors, many of them maimed, returned home from the Wars adding to the national unemployment and destitution. The situation was exacerbated by appalling weather that had led to crop reduction and failure. Income Tax, which had been introduced to raise money during the wars, was abolished when peace was declared and replaced by taxes on staple commodities. These included such necessities as candles, paper and soap as well as luxury items such as sugar, beer and tobacco. As the economy slid further into the mire, the Poor Law relief rates were slashed and death through starvation was commonplace.

Up until the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars, Dover ship owners, particularly the Fectors and the Latham/Rice families, provided most of the packet service ships that carried mails to and from the Continent. At the outbreak of the Wars this and passenger services were moved to Harwich while official cross Channel passenger and freight services from Dover were suspended. Then, in 1799 a regular stage coach service between Dover and London was introduced and shortly after a weekly mail coach. A packet service of sorts developed and although supposedly administered by the Admiralty this was effectively again run by the Fector and Latham/Rice families. Following the renewal of hostilities in 1803, the Admiralty almost abandoned the packet service to the local businessmen but on 10 October 1815, it was officially resumed under the auspices of the Admiralty. Nonetheless, it remained locally run.

The Dover built ships plying between Dover and Calais as packet and passage ships and along the coast, when work was available at this time were:

Ant – Master: T Barrett

Chichester – Master John Whitfield Rutter (1773-1825)

Cumberland – Master: John Hammond (1780-1854)

Dart – Master: M Bushell

Defence – Master: John Adams (1768-1835)

Elizabeth – Master: William Bushell (1782-1855)

Flora – Master: Archibald Watson (1780-1831)

Industry – Master: Tasmin Archer

King George I – Master: Michael King

King George II – Master:Thomas Mercer (b1791)

Lady Chasteragh – Master: William Mowll (1787-1872)

Lady Jane James – Master: John Hayward (1770-1838)

Lark – Master: T Noyce

Lord Duncan – Master: John Hamilton (1783-1859),

Lord Sidmouth – Master: Allen Peake (1764-1823)

Poll – Master: W Strains

Prince Leopold – Master: William Rogers (1763-1839)

Susanna – Master: Thomas Middleton (1751-1835)

Vigilant – Master: Stephen Bushell

Locally, it was assumed that the economic depression would be dealt with by the age old standby, smuggling. For much of the 18th the shipbuilding industry had expanded due to the illicit trade, it had provided employment for these ships and adequate income for the captains and crew with the knock-on effect for the town as a whole. However, the depth and extent of the depression meant that except for smuggled imported corn and other food grains, there was even a slump in the interest of formerly sought after luxury goods. This enabled to government to take a hard line against smuggling and in 1816, the Coastal Blockade was established.

The Admiralty frigates, Ganymede, Ramillies, and Severn, were put under the command of Captain ‘Flogging’ Joseph McCulloch, who proceeded to wage a merciless war on smuggling. Albeit, for some of Dover’s shipbuilders, this gave a respite in the post war economic depression as the government ordered new galleys for the newly formed Coastal Blockade. This was based on the reputation of Dover built ships being so fast they could outrun the Admiralty frigates. The respite, however, was too little too late. For instance, an order for a fast running sloop was placed with shipbuilders Pascall & Hedgecock but on 27 April 1817 the partnership, that had existed since 1797 and Pascall’s shipbuilding business, since 1732, was dissolved. The young James Hedgecock (b1800), had served his apprenticeship with the firm and in 1820 ran the company, still trading as William Hedgecock (b1765) and based in Beach Street tried to keep the business going. He built ships for the Customs and Excise but by the end of the decade Hedgecock’s ceased to exist.

The prevailing economic climate deeply affected Dover’s shipbuilding industry but the situation was inspiring innovations in the industry itself with the advent of ships driven by steam power. Steam powered vessels had actually been around since the end of the 18th century and in 1794 an experimental steam powered ship called the Kent was built. She was followed in 1801 by the steam tugs Charlotte Dundas 1 and 2, which worked on the Forth and Clyde canal near Glasgow. In 1812, the Comet successfully started operating between Glasgow and Helensburgh, to the north and west of the city. Like all early steam ships, the hulls retained the features appertaining to sailing ships and full sets of sails were also carried partly to increase speed as well as counteracting the lack of confidence in mechanical propulsion.

Meanwhile, in the face of shortage of food, Dover’s shipping owners Sam and Henshaw Latham managed to arrange for grain to be brought from the Continent with Henshaw recording on 9 February 1819, from Antwerp:

the sloop Wensleydale – Captain Partridge

the sloop Teazer – Captain Rogers

the sloop Lord Hill Captain Tapley

the sloop Favourite Captain Power from Ostend

all laden with wheat

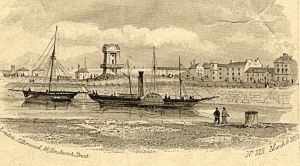

In March 1819 the Elsie, a 37-ton steamboat, crossed the Channel and on 20 June, the steamship Savannah, with the help of sails, took 26 days to cross the Atlantic. The year before, on 14 June, the first paddle steam packet, Rob Roy, had made her first crossing from Belfast to the Clyde and on Friday 15 June 1820 she was introduced to the Dover-Calais passage. Taking 4½hrs to cross the Strait, the 88-ton ship was built by Denny of Dumbarton with 33 horsepower engines by Daniel Napier. The French government, attracted by the idea of steam, purchased Rob Roy, gave her the name of Henri Quatre and she subsequently worked the Calais-Dover packet run. The British government, impressed with steam packets, in 1822 introduced the Monarch and Sovereign.

The 70 ton sailing ship George I owned by the Fector’s and hired by the Post Office as a supplementary packet ship

George III (1760-1820) died on 29 January 1820, he had been deemed incapable of ruling the country since 1811. Since then, his son, now George IV (1820-1830), had reigned as Regent and for his Coronation, his estranged Queen Caroline (1768-1821), was brought to England. She arrived in Dover on 5 June 1820 having crossed the Channel aboard the Prince Leopold, a Fector Packet sailing-ship under Master William Rogers. The Queen was given a tumultuous welcome plus a royal salute from the commandant of the garrison as well as a guard of honour! George IV, was furious and although by the following year the Queen was dead, as a form of retaliation the government gave the packet service contract to the Post Office. They introduced the Arrow and the Dasher, both wooden paddle steamers neither of which were built in Dover. The 149 gross ton Arrow had been built by William Elias Evans of Rotherhithe and the 130 gross ton Dasher by W Paterson, also of Rotherhithe. The Post Office added to their fleet the second-hand sailing ships Aukland, Eclipse, Chichester, King George I and the Lord Duncan. The 384ton Eclipse had been built by the King shipyard and bought by the Post Office for £1,400. The last three were 60 to 70 ton Dover built sloops.

The 1820s saw a growth in the number of shipbuilders and associated professions who could still make a living such that they were still major businesses in Dover. By 1824 shipbuilders consisted of Richard Bromley of Fisherman’s Row, John Divine of Bakers Lane, James Duke (1791-1882) off South Pier and Kiazer Thornton of Snargate Street. The long time establishments of John Gilbee (1742-1815) and James Johnson (c1760-1824), who was part of a sail making family, were thriving. Both establishments were on Snargate over Sluice now Union Street and again the long time established John Freeman firm along with William Hedgecock’s business (see above), Hubbard and Clark and Henry Pilcher all on Beach Street next to Shakespeare Beach were also making a living.

Sailmakers were Philip Going (1795-1859) & Co. of Round Tower Street, Thomas Randall (1766-1835) on Fisherman’s Row, Thomas Spice (1765-1839) on Snargate over Sluice, Richard Hart, William Robinson (1801-1834), both on the Quay Side. The long since establishment of Peter Popkiss, former holder of the Post Office shipping contract, was based in Post Office Lane off Snargate Street. Albeit, of the four ropemakers operating in 1792, only Richard Jell (1762-1847) remained but in the 1820s Edward Frost of Limekiln Street had set up a ropemaking business. Thomas Ismay’s, ship chandling business still remained but had diversified into iron making, while John Osborn was in partnership with Messr Poole to create a ship chandlers, ironmongers and iron foundry business on Snargate Street.

The poor state of Dover’s harbour was due to neglect during the Wars, exacerbated by debt repayments from works that had been carried out. The Dover Harbour Commissioners’ main source of income was from tonnage dues and these, due to falling in trade had declined year on year since the end of the War. In 1820, Sir Henry Chudleigh Oxenden (1795-1889), the Harbour Commission’s Managing Commissioner loaned £4,500 and in June 1822 £1,500. Later he loaned a further £2,500, all at 4% interest, but this was of little help. The Harbour Commission therefore appealed to Parliament who set up a Committee on Foreign Trade to assess the situation. The Harbour Commissioners put forward an excellent case centring on increasing grants and, perhaps, the percentage tonnage dues paid. The Committee’s response, however, was the opposite of what the town had hoped. Their report stated that due to the fall in trade it would be unfair to increase tonnage dues and therefore decreased them adding that in their opinion the fall in trade was a temporary problem. As for grants, they said that when trade increased, the amount of money from tonnage dues would increase so saw little point in providing grants.

The shipbuilders recognised that the future of the industry was with steam ships but to reduce the risk of fire, they had to be built of iron instead of wood. In consequence, there was a need for iron foundries and dry docks. The first step in building a steam ship as with sailing ships, was to lay the keel using keel blocks to support the ship as it was being built. Although this could be carried out on the beach, as with sailing ships, the next stage was assembling the iron plates to form the hull and held by the use of giant nuts and bolts / screws. Due to the weight and size of the hull it was at this stage that dry docks were a necessity to be successful. Once this was achieved, then the ship could be launched out of the dry dock for the outfitting – so the installation of the engines, paddles etc. could begin.

However, the shipbuilders, the town, nor the Harbour Commissioners, even jointly, could afford to build a dry dock. Adapting what resources they had, the shipbuilders ventured into building steam-powered ships on the beach and in 1823, the Monarch, one of the country’s earliest paddle steam ships, was built on Shakespeare Beach. She was 100 tons, engined by Maudslay, Sons & Field, London, of nearly forty horsepower. She was put into service by the Post Office, on 30 April 1824, on the Dover-Boulogne route but due to catastrophic engine failure she was withdrawn from service and sold. Not long after the slightly larger Sovereign was built, but the Post Office was disinclined to buy anymore Dover built steam or sailing ships. Instead they acquired the 110 gross ton 83-foot Spitfire, a wooden paddle steamer with 40 horsepower engines built by Graham’s of Harwich in 1824. The wooden paddle steamer Fury also built by Graham’s of Harwich was also brought into service. Then in 1825, the American and Colonial Steam Navigation Company placed an order for a paddle steamship with the Duke shipyard. James Duke (1791-1881), who was joined by his son Robert (1827-1883) ran operating as J.H. & J Duke and the business continued until 1867.

The Duke shipyard built the Calpe for the American and Colonial Steam Navigation Company on Shakespeare Beach at the back of their home and works on the long since demolished Beach Street. She was 134feet in length, 438 tons register and was powered by a Maudslay 2-cylinder side-lever engine with a capability of 8mph. The boilers in the Calpe weighed more than 100 tons! However, by the time she was launched, the American Company had changed their minds and cancelled their order.

The Curaçao, formerly the Calpe, built in Dover and one of the first steam ships to cross the Atlantic. Dover Harbour Board.

At the time, across the Channel, the Royal Netherlands Navy were also building steam-powered ships. Of these, one was for service in the Far East, and another in the West Indies. The first ship was built in Seraing, Liege, Belgium and fitted with Cockeril engines but the engines were too heavy and following tests the contract was withdrawn. Impressed by Dover’s shipbuilding expertise during the Napoleonic Wars, King William I of the Netherlands (1815-1840) ordered the Royal Netherlands Navy to replace it with a steam powered ship from Dover. The Duke’s were looking for a buyer for the Calpe and in October 1826 they sold her to the Netherlands Navy who renamed her Curaçao. Although without arms and with interiors for discerning private passngers, she was commissioned as ‘a man of war’! The Curaçao made her maiden voyage to Hellevoetsluis, near Rotterdam, where she was loaded with 400 tons of coal, mail, valuable freight and private passengers. On 26 April 1827, the Curaçao embarked for the Dutch West Indies and arrived at Paramaribo, Suriname, South America, on the 24 May. According to one account, her engines were used for 11 days, while another states that they were used throughout the journey.

The Curaçao’s next port of call was her namesake, the island of Curaçao, in the Dutch Antilles, where she took on fresh water. On 6 July, she embarked for the return journey arriving in Rotterdam on 4 August. For the first 22 days the crossing was under steam but due to a combination of saline scale in the boiler plus boiler leakage causing overheating and then broken paddles, the last week was under sail. In 1828, the Curaçao made a second and in 1829 a third crossing of the Atlantic and thereafter, she regularly made the crossing. In 1834, Englishman, Samuel Hall (1781-1863), patented the surface condenser, which was the first efficient means of reconstituting fresh water from steam and re-using it. The first crossing of the Atlantic entirely under steam is said to have taken place in 1838, when the British ship Sirius, with a Hall condenser, successfully made the crossing from Cork, Ireland, to New York. Albeit, it was also officially reported that the Curaçao, fitted with a Hall condenser, successfully made the crossing two years earlier. The Curaçao remained part of the Royal Netherlands fleet as a man-of-war until 1848 when she was sold for 9,500 florins and replaced by a second ship of the same name. Although, the Curaçao was recognised as the first ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean under steam and both ways, sadly, internationally this Dover built ship has never secured this rightful accolade.

With the success of the Calpe/ Curaçao it was hoped that similar orders would be placed in Dover. However, the Battle of Navarino, Greece, in 20 October 1827 was the last to be fought by the Royal Navy entirely with sailing ships and they turned to steamships built in the Royal dockyards of Portsmouth (founded 1496), Royal Dockyard at Woolwich (founded 1513) and the Royal Dockyard Chatham (founded 1547). The Government run Post Office, having no loyalty to the town, preferred the Thames based ship builders.

Adaptations for smuggling purposes were still undertaken by Dover’s shipbuilders though due to the continual tightening of anti-smuggling legislation, the industry was no longer run by wealthy businessmen. Indeed, their children became the leaders of the ‘respectable’ classes and took leading roles in the equally lucrative national and local politics together with property development. Typically, local businessmen, Edward Knocker (1804-1884), William Prescott (1805-1869), John Finnis, and Henry Elve (1803-1865), in 1829, bought landholdings on the east side of the Dour from the Market Square for £2,000. Edward Knocker, purchased the Castle Hill House and estate for £7,000 and evidence suggests that the money for both purchases came from the wealth acquired by smuggling. The members of the consortium were all the members of the Dover Paving Commission, which over-saw Dover’s building projects and they planned to develop their newly acquired landholdings. These became Castle Street and the southern end of the later renamed Maison Dieu Road and nearby streets.

Paddle Steam Packets

Calais passengers preparing to board a sailing packet ship c1803 during bad weather. Joseph Mallard-Turner

When asked by a parliament committee, the Post Office stated that they and their passengers preferred steam packets to the cheaper to buy and run sailing ships. Further, since surface condensers, patented by Samuel Hall, had been introduced the constant need for fresh water for the boilers was adequately dealt with. They also said that steam packets were not so vulnerable to wind conditions as sailing ships. On 9 August 1833, the Post Office introduced a daily service between Dover and Calais, weather permitting, except on Sundays. Weather permitting being the salient requirement as Calais harbour was neither easy to enter nor exit for steam packets in bad weather, while Dover was impossible. On such occasions, the Post Office ships were forced to anchor in the Downs, off Deal, until the weather abated. In the meantime they used their remaining sailing ships to make the crossing but emphasised, to another parliamentary committee, that this could take up to twelve hours. Then, in 1834, Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) made the crossing from France to England having travelled from Rome. This was on a fine day and he praised the ‘up-to-date advantage of a well fitted steam packet‘. Henceforth, this became the advertising slogan of the Channel packet industry and sailing ships were phased out.

In 1835, following the introduction of the Municipal Corporations Act, the running of Dover passed from Dover council and the Paving Commission into the hands of a new body, Dover Corporation. Although elected councillors were in charge and the Paving Commission ceased to exist, power effectively remained in the same hands. The poor state of Dover harbour remained the main concern of the now much stronger corporation, added to which they were able to emphasise the lack of provision of a Harbour of Refuge on the South East Coast. Using all the publicity they could muster and with the full backing of the Harbour Commissioners, the corporation turned their concerns into a major national worry.

Paddle steam ship in Dover. The pilots tower at the western side of the harbour can be seen. Dover Museum

As a result, the following year, Parliament set up a Commission to Inquire into the state of Dover Harbour. At the Inquiry, it became apparent that work had already started on deepening the Great Pent, between the Dour River and the Tidal Basin with its outlet to the sea. This, it was stated, was to enable the new Post office steam packets safe berths when not in use. The result was that in December 1836, the running of the Dover packet service was passed to the Admiralty although the Post Office regulated the times of departure. The Admiralty increased the number of steamships, though none were built in Dover. Dover town fathers’, ignored the declining needs of the shipbuilding industry and turned their full attention to the proposed South Eastern Railway Company’s (SER) rail link to London and with it, the urgent need for a larger and safer harbour that would also serve as a Harbour of Refuge.

Nationally, in 1837, Swedish Captain John Ericsson (1803-1889) and independently, Francis Pettit Smith (1808-1874) successfully demonstrated screw propeller propulsion. As this was submerged all of the time, the new type of propeller provided more power than paddle propulsion and was less vulnerable to storm damage. Metal hulls had been around since 1777 but it was the wrought iron hulled, screwed propelled Great Britain, built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) at Bristol and launched in 1843 that led the way. Locally, the SER was still building the railway line from London to the town but had extended and modernised the tiny Folkestone fishing harbour and laid a spur railway line from the main London line in order to create the Company’s principal cross Channel port to France. Except for passengers going to Ostend, the direct railway link via Folkestone harbour, to the Channel and France attracted passengers going there and in consequence, Dover’s packet trade suffered.

South Eastern Railway ran on trestles along the edge of Shakespeare Beach, below the cliffs, and where shipbuilders had their businesses. Dover Library

On 6 February 1844, SER officially opened their Dover station, renamed Town Station in 1863. Because the Company had taken the line as close to Folkestone as possible in order to create a cross Channel port, the shortest route from there to Dover was below the cliffs. The line ran along Shakespeare Beach on raised trestles and there, the remaining Dover shipbuilders plied their trade. As William Batcheller (1777-1858) wrote at the time, ‘… will clear away Beach Street, the whole of Seven Star Street, which will include nearly all the ship builders in Dover, not even excepting Mr Duke, whose residence will also come down.’ James Duke, whose home was on Fishermans Row where he owned three other houses that were demolished, asked the Railway Company for £9,000 in compensation for the loss of his shipbuilding yard and home. According to the surviving documentation, his shipbuilding business included a blacksmiths forge that he leased; a sawpit, shed, timberyard, steam boilers, and workshops all situated on the beach by the South Pier. Also an adjoining masthouse, boatshops and sail lofts.

Witness box in the former Court Hall, the Maison Dieu, where the shipbuilders compensation hearings were held. Alan Sencicle

The Company refused to pay any compensation so the shipbuilders were obliged to bring legal action. Duke and Cullin’s shipyards filed petitions and the Duke case was heard in August 1843 in the then Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu. Lasting two days, from the outset the court reflected the general view of the town, they needed the railway and therefore no sympathy was shown to the Duke shipbuilding company or any other shipbuilders who had lost their livelihood. Dover Harbour Commissioners, mindful that the shipbuilders occupied Harbour Commission land and paid good rent, stated that they planned to provide shipbuilding facilities around the Great Pent that was undergoing major refurbishment, becoming the renamed Wellington Dock. Thus, in recognition to Duke’s loss of property and to a lesser extent, his business, the jury awarded him £4.050. The outcome set the precedent for the other shipyards proposing to seek compensation with some following Cullin’s shipyard by settling privately.

Thomas Vincer (1821-1859) and his son applied for compensation and out of what they received they bought a smaller operation on Finnis Hill off Limekiln Street. Vincer’s other sons left the business, becoming mariners and following the death of Thomas Vincer the shipbuilding yard closed in 1859. Hannah Freeman, widow of shipbuilder John Freeman (1759-1831), successfully sought compensation. At the time she had leased the Freeman yard to mariner William Dixon, whose son Richard had served his apprenticeship under John Freeman and was running the yard. Others seeking compensation included John Finnis who was involved in the Castle Street development and owned a substantial amount of property in the Pier District including sixteen houses and two warehouses. Finnis’s Pier district properties were all demolished and his compensation was settled by private negotiations through his solicitor. The Mulberry Tree Inn, established possibly in 1790, on the edge of Shakespeare Beach under Archcliffe Fort, kept by William Gravener, was demolished along with the ropewalk and factory, by this time owned by a John Jones. His compensation was settled by jury and he was awarded £1,156.11 shillings.

Refurbishment of the Great Pent, on completion renamed Wellington Dock, to where the displaced shipbuilders moved. Dover Harbour Board.

The Harbour Commissioners kept their word and shipbuilders were invited to set up close to the refurbished Great Pent. This had begun in the 1830s with the deepening and then lining with granite blocks. Giant lock gates were inserted to provide access and egress between the new dock and the Tidal Basin. Additionally, an iron bridge was built over them and the whole enterprise was completed in 1844 at a cost of about £45,000. The Lord Warden, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) opened and gave his name to the refurbished dock on the 13 November 1846. Sluices were inserted at the side of the dock gates to relieve over filling from the Dour during stormy weather. Once operational, the Wellington Dock proved to be a financial blessing with the revenue from Passing Tolls increasing to £10,000 a year.

After SER completed their railway line to Dover, passengers travelling to France, still preferred to travel from Folkestone rather than Dover forcing the Admiralty to reinvent the packet service from Dover. They introduced a number of new steamships to Dover for the crossings to Calais and Ostend. In order that major as well as minor repairs could be undertaken at the port, they constructed a modern fully operational Packet Yard. Erected near Custom House Quay, Strond Street, on the Snargate Street side of the then Bason, later Granville Dock, it remained there until 1860 when it was replaced by much larger premises on the north side of Snargate Street.

Dover’s golden age of shipbuilding had drawn to a close but a few did take up the Harbour Commissioners offer and many shipwrights sought employment at the Packet Yard. However, the number of coal merchants in the town were increasing. In 1831, not long after the Dover built paddle steamer Calpe / Curaçao had been sold to the Royal Netherlands Navy and was crossing the Atlantic, there were three coal merchants. By 1841 there were twelve and although this was partly due an increase in industrial and household demand for coal, by their location, most can be directly attributed to the use of coal for bunkering steam vessels.

Dover’s Shipbuilding moves to Wellington Dock

On the south side of the Wellington Dock is Cambridge Road named after Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (1774-1850). It was laid out by the Harbour Commissioners in 1834 and handed over to the Paving Commission the following year. On the south side of Cambridge Road, facing the sea, Waterloo Crescent was built between 1834 and 1838 as the final part of a Harbour Commissioners building programme to attract wealthy Londoner’s to rent the elegant seaside properties. On the land between Cambridge Road and Wellington Dock what became Ordnance Stores and wharf was built and completed in 1845. Two years later, in 1847, after considerable pressure by Dover folk, local politicians, Harbour Commissioners and the Duke of Wellington for Dover to become a Harbour of Refuge, work on the Admiralty Pier began. Although only the western arm of the Harbour of Refuge – the Admiralty Pier – was completed and this was not until 1871.

The ubiquitous trade directories of the time gave shipbuilding, sail and rope making as well as paper making, corn grinding and oil crushing as Dover’s main occupations. Of the shipbuilders, the 1847 Bradshaw listed James Duke operating alongside Commercial Quay, the only purpose built quay at Wellington Dock and were on the north side. Robert Johnson was running Cullin’s shipyard close to the Ropewalk at the foot of Aycliffe. At the time the provision of shipping artefacts and repairing of iron work was by shipsmiths, of which there were three Thomas Ismay (1812-1881), son of Thomas Ismay (1747-1827) operating from the Crosswall, Poole and Alderton of 98 Snargate Street and Thomas Walters of 92 Snargate Street.

Dover’s sailmakers included Going and Debenham of Commercial Quay, John Johnson (bc1790-1854) of Union Street and 14 Limekiln Street, William Johnson (b1831) of 89 Limekiln Street and Robert Spice (1792-1867) of Council House Street. John Johnson’s home was 10 High Street, Charlton, and when he died in 1854, his estate was sold by auction and included the contents of a sail loft at Wellington Bridge. There were three ropemakers operating at this time, Edward I. Pittock of 18 Hawksbury Street, Thomas Dennis (1814-1876) of the Princess Maud Inn, Hawksbury Street and John Pittock of 13 Strond Street. John Pittock had established himself as a ropemaker in the 1820’s at Aycliffe, Due to the opening of the South Eastern Railway Company along the beach, the Aycliffe ropewalk was the only one left in the town. Ship Chandlers were William Johnson of Union Street and John Wrightson (b1811) of 61 Snargate Street and in Charlton, there was Thomas Smith with premises at 6 Charlton Terrace in the High Street and William Smith in Spring Gardens.

The main type of ships that were being built were fishing smacks and the occasional pilot ketch that the shipbuilder maintained on a regular basis. The term smack was applied to any type of decked or half decked boat with one-mast, a mainsail, two headsails and a bowsprit. The Admiralty packet ships were repaired at their Packet Yard along with others ships. The work they and independent shipbuilders and ancillary occupations carried out depended on the type of ship, the damage it had sustained and the treatment of the vessel before it required repairing. As the Channel was particularly hazardous, as the 19th century progressed, an increasing number of ships were brought to Dover for repairs. Mainly as a result of the number of ships traversing along the Channel and crossing the Channel as well as rough or foggy/murky weather conditions. The different occupations in Dover were highly skilled such that no matter what the damage was, as long as the ship’s damage was not too large – Dover did not have a sufficiently large dry dock – repairs were undertaken. Oak, the favoured wood of the past had generally been replaced with the cheaper pitch-pine (Pinus rigida) for wooden vessels and the Channel’s heavy weather ensured they easily succumbed to damage. Ironwork damage to hulls was usually caused by collisions and the increasing number of these ensured the growth of the associated highly skilled repairing occupations.

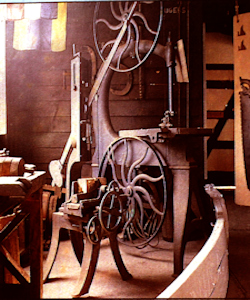

In March 1852, the Harbour Commissioners appointed Henry Lee & Sons of Chiswell Street, London to construct quays all the way round Wellington Dock. Additionally, wooden sheds were erected between the Dock and Cambridge Road for shipbuilders and associated industries. Two years before, in 1850, using the mud and the excavating track from building Wellington Dock, a slipway and quay, capable of handling vessels up to 175-feet (53.34 metres) in length and up to 550 tons register were built. The slipway was 567 feet (173 metres), at the time long enough to take two vessels, and the length of the cradle was 175feet (53 metres) and stone lined. To pull ships and boats up, there was a powerful boiler driven engine. In order to accommodate two vessels of up to 800tons in 1883 the slipway was lengthened, strengthened and widened A new boiler was installed to give the engine that pulled up the vessels additional power.

In using the slipway, the Harbour Master 1832-1860 – John Iron I (1744-1867) – or one of his deputies and their successors, would first find out the length of the vessel’s keel and the rise of the bilge. Bilge blocks would then be inserted on each side of the ship with keel blocks laid to the required length. The cradle was then lowered down the slipway and into the water by wheels on three rails to the depth that the vessels drew. The ship was then moved into position over the cradle and steadied by ropes. The cradle was then hoved up by the slipway steam engine. As soon as the vessel grounded the aft keel blocks and the bilge blocks were drawn under by ropes and secured. The cradle, with the vessel on it, was then hauled up the slipway as far as required. Should there be more ships needing repairs than room for, they had to wait their turn alongside Slip Quay. The last wooden vessel to be was built on the slipway was in 1878 and the last ship to use it was the Admiral Day, the Dover Harbour Board’s dredger, in 1993. Four years later, in 1997, Dover Harbour Board reclaimed the slipway area for the De Bradelei Wharf shopping development. At the upper level, the carriage lines could still be seen until recently.

The Dover Harbour Commission was reconstituted to the Dover Harbour Board (DHB) in 1861 and in 1868 the new Harbour Board, purchased the Fairbairn Hand Cranked Crane. This was to lift heavy shipping gear into and out of the ships and hoist smaller vessels in and out of Wellington Dock. The crane was designed and made by William Fairbairn (1789-1874), who was born in Kelso, Scotland, the son of a farmer. Apprenticed to a wheelwright, Fairbairn met and became friends of engineer George Stephenson (1781-1848) who inspired Fairbairn to set up a business in Manchester. There he designed and made machinery, including cranes, for cotton mills. In 1830, Fairbairn diversified into the iron boat building business opening a shipyard at Millwall, London where built several hundred vessels. As a shipbuilder, one of the problems Fairbairn faced was lifting the heavy metal parts into his ships. He therefore adapted his design for cotton mill cranes to shipbuilding. The Fairbairn crane, which can still be seen, is a designated Ancient Monument and has Grade II listing.

1871 saw the completion of the original 2,100-feet long Admiralty Pier, then later extended, which cost £693,077 to build. At the time ships tied up on both sides and thus it provided significant anchorage and shelter. Although, the much-needed Harbour of Refuge was showing no sign of ever being built, on 24 July that year the Dover Harbour Improvement Bill received Royal Assent. This enabled work to begin on deepening the Bason allowing vessels drawing up to 21-feet to enter at high water. Following completion, the dock was opened by the Lord Warden, Earl of Granville – George Leveson Gower (1815-1891), on 6 July 1874. The refurbished dock was renamed Granville Dock. Along Cambridge Road, Dover Harbour Board replaced the sheds used by shipbuilders and ancillary occupations with the purpose designed brick buildings that we see today. During the 1880s these were enlarged to accommodate the increase in space required by the shipbuilders.

By this time, more efficient ships’ engines were being introduced and from the 1880s steel began to replace iron for the hulls. These ships were larger than their predecessors not only to accommodate the engines but also to provide for the space required to store coal and the increase in the number of passengers and crew carried as well as cargo. Although the Dover fishing industry was on the wane, there was still a call for new fishing boats that were being built by the Dover shipbuilders.

Aerial View of Dover c1910, at the height of the town’s affluence and as a tourist holiday resort. Bob Hollingsbee Collection

For recreational purposes the yacht was growing in popularity with these vessels typically being built around the Solent, the strait between the mainland and the Isle of Wight, or along the banks of the Thames. However, in 1870, owner of a large emporium in Market Lane and Mayor, Richard Dickeson (1823-1900) was elected the Chairman of Dover’s Regatta Committee and was determined that the club would produce nationally competitive racing teams. Over the following 26-years he presented a new Dover built racing galley to the club as well as providing specially Dover designed rowing boats to encourage Dover’s rowing crews. With this help, the club’s Senior Four were merited as being the most outstanding crew in Britain! Tourism had also taken off and during the season the lodging-houses were crowded with visitors. The knock-on effect for shipbuilders was an increase in the demand for small pleasure boats and cruisers. However, it was in repairing of ships that the shipyards received most of their lucrative work.

The Packet Yard (1859-1991) on Snargate Street and one of the town’s main land based maritime employers. Map c1900

The Packet Yard on Snargate Street, was owned by the London, Chatham & Dover Railway Company under the Chairmanship of James Staats Forbes (1823-1904). It employed 250 men with the combined weekly pay of £310 and locally headed by Ralph Kirtley. The main objective of the works was to keep in good repair, the Dover and Calais packet fleet. At this time there was 16 vessels, with the total indicated horsepower of 30,195. The aggregate number of voyages each year was approximately 3,088. Independently, according to the 1887 Dover Trade Directory, there were three shipbuilders/shipwrights operating at this time. They were James Arthur Beeching (1839-1897) and Edgar Samuel Beeching (1861-1927) operating from the DHB workshops in Cambridge Road and William Johnson Cullin (1839-1892) and Sons also based in the workshops. At 141 London Road, Buckland, there was Arthur Verey (1841-1921) & Co who specialised in building steam yachts.

Beeching shipbuilders, Wellington Dock with Dover Fishing smack DR 11, Surpise nearer to the camera. Dover Library

Both Beeching and Cullin shipyards abutted the Wellington Dock slipway and both firms mainly produced fishing smacks from forty to fifty tons register. The models of which lined the office walls. Both shipbuilders also had their own fleet of fishing smacks. The Cullin shipyard could trace their history as shipbuilders in Dover back to 1638 (see Shipbuilders part I). Some fifty years after the Cullin family opened their shipyard, William Beeching, a cordwinder married Alice Randall and took over running Buckland corn mill. What happened next is difficult to ascertain other than members of the Beeching family, with Norfolk connections, settled in Dover and eventually opened a shipyard on Dover beach. This did not seem to survive after the Napoleonic Wars but a Norfolk relative, journeyman shipwright James Beeching, opened or took over the derelict yard in the 1860s.

In November 1888, a Dover Express reporter described the shipyard as thriving and containing a number of relatively newly built lofts for carrying on the historic branches of the trade, see Shipbuilding part I. Added to which there was a moulding loft, where moulds were made to the form of the timbers that were used. Cutting of the timbers to the required shape was carried out by master shipbuilders, by this time, using specially designed machines. There was also a large stock of seasoned timber suitable for the various works that the yard carried out, but this was mainly repairs. Although both Cullin and Beeching were keen to build larger vessels, the harbour only had a small dry dock just adequate for building fishing smacks and ships of that size. Albeit, when it came to repairs, Dover shipbuilders and shipwrights were termed ‘double handed’ as they could undertake all manner of ship repairs and were well favoured by European shipping companies.

Sailmakers and Ship Chandlers, Sharp and Enright’s shop on Commercial Quay in the 1920s. In the following decade they moved to their present Snargate Street premises when Commercial Quay was demolished. Hollingsbee Collection.

The 1887 Trade Directory lists three shipsmiths whose trade it was to repair ships metal work. They were Day, Hill & Co. of Snargate Street, Alfred Henry Gutsole (1833-1917) of 4 Commercial Quay and Miss Ewell who had business premises at 51 Oxenden Street and on Water Lane. There were also four sailmakers, J W Bishop 77 Snargate Street, R Blackford 21 Limekiln Street and William James Simpson (bcirca 1861) Strond Street. Thomas Spice who had a sailmaking business on Snargate-over-Sluice and later in the Old Buildings, 115 Snargate Street, in 1839. On his death, sailmaker Robert Thomas Stanton (1834-1887) from Deal, who lived at 69 Limekiln Street, bought the business. He was also the landlord of the Royal Oak, 38 Oxenden Street in the Pier District, had a fishing smack named Deerhound and ran his sailmaking business, which included rope-spinning and chandlery, from premises at 17 Commercial Quay. By 1887, Stanton was the landlord of the Crusader Inn, 29 Council House Street, also in the Pier District, as well as being involved in his other enterprises. However, on 18 June 1887 Stanton committed suicide by hanging at his sail loft in Blenheim Square in Dover. After the inquest, the shop was sold and the Deerhound, his sail loft and his share in the ropewalk at Aycliffe were auctioned.

The shop was then bought by sailmakers John Enright (1837-1889) and John Sharp (1832-1906) plus two sleeping partners. They were Ernest Ardlie Marsh (1837-1938) and William Grant (1855-1925) who were connected with the shipping firm of George Hammond in Union Street. Sydney Sharp (1873-1956), the son of John, bought out the sleeping partners and ran the firm until World War II (1939-1945) by which time chandlery was the main business. Dover Harbour Board demolished Commercial Quay for dock development in the late 1920s and the firm, Sharp & Enright moved one street back to almost identical premises in Snargate Street.

Admiralty Pier during the construction of the extension with the former SER railway line going west and the former LCDR line going north. A steamer can be seen tied up against the outside of the Pier and boat builders on Shakespeare Beach Dover Library

By the turn of the century Dover’s Packet Yard, with its head office at 91 Snargate Street, was the town’s largest maritime support service employing shipwrights, shipsmiths and the other of the town’s ancillary professions. By this time the Yard was maintaining ships from other ports belonging to the recently formed South Eastern and Chatham Railway Company (SECR). This had come into operation on 1 January 1899 with the amalgamation of South Eastern Railway Company and the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company, these two railway companies serving the county of Kent. The Packet Yard was also maintaining and repairing freight ships as well as other large maritime vessels from elsewhere. To improve and expand this service SECR, along with Dover Harbour Board (DHB) and Dover Corporation tried to pressure the government into building a large dry dock. Estimated to cost £50,000, SECR announced they would contribute £10,000 towards it but due to other financial commitments neither DHB nor the Corporation could, even jointly, make up the difference.

At the end of 1891, Parliament had agreed to lease the Admiralty Pier to DHB for 99 years and a start was made on an eastern pier of the much-needed Harbour of Refuge. For this, Parliament had sanctioned for the work to be paid for by a poll tax of 1 shilling (5pence) on each cross Channel passenger. On 20 July 1893, the first stone of the eastern arm of the project was laid by Edward Prince of Wales, later Edward VII (1901-1910) and was named the Prince of Wales Pier.

While this was underway, DHB submitted a Bill to Parliament for building a ‘Water Station’ with four railway tracks and berths for four cross-Channel steamers all under cover between the Admiralty and Prince of Wales Piers. The final estimated cost was £1,750,000 and to pay for these works the poll tax was to be increased on cross-Channel passengers. Albeit, on the international stage tension was rising. From 1890, Germany, under Wilhelm II (1888-1918), had been pursuing a massive naval expansion. In May 1895, when about three-quarters of the Prince of Wales Pier had been built, the Admiralty announced that it was going to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy and work started on the Admiralty Harbour that we see today. This was opened by George Prince of Wales later George V (1910-1936) on Friday 15 October 1909 but it did not include the proposed ‘Water Station’ nor the much needed large dry dock to maintain Dover’s role in ship building or as major ship repairers.

In 1903 part of the Cambridge Road premises used by the independent shipbuilders were rebuilt and taken over by the Marine Department of SECR, that let the western end out to William Cullin, the proprietor of the family shipyard. In the 1899 Trades Directory the Beeching shipyard was listed at their former address but by 1909 it had gone. Further down Cambridge Road, the Harbour Board enclosed the yard, in which the Fairbairn crane stood and from there to Wellington Bridge created an open quay. By this time, Dover’s only sailmakers were Sharp and Enright and a new company run by Shilson and Thorpe of 23 Worthington Street and Round Tower Street.

The former Dover Engineering Works at Charlton Green. The company had its origin as shipsmiths, an arm of ship building.

Alfred Gutsole was still in business as an independent shipsmith and also as independent shipsmiths was A L Thomas and Sons of 93b Snargate Street. Run by Anthony Lewis Thomas (1806-1878), he ran a jobbing foundry on Charlton Green, which continued after his death. By that time the foundry particularly specialised in manhole covers and street lamps. In 1902 it became a limited company and by 1908, Dover Mayor, Thomas Walter Lawrence Emden (1847-1913), owned a controlling number of ordinary shares and put his nephew, Vivian Elkington (1880-1963), in charge. Elkington, who lived in Granville Road, St Margaret’s Bay, introduced marine engineering to the business and it was renamed Dover Engineering Works Ltd. During World War I (1914-1918), the company was responsible for maintaining the two-hundred-strong fleet of the Dover Patrol. Following the War the company mainly specialized in developing manhole covers and in 1928 developed what became the internationally known Gatic Cover (Gas & Air Tight Inspection Cover). In 1963, at the height of the Engineering Works success, Vivian Elkington died aged 83.

The fall of Dover’s Shipbuilding and Repairing industries

Prior to World War I the town Dover basked in prosperity as the Admiralty Harbour was built and the tourist industry attracted increasing number of visitors from the county, London and the Continent. Cruise liners, enroute between Europe and the USA, called in at the port and Dover’s retail sector sold products from home and abroad, many of which could not be bought in London! Indeed, Dover was in the top ten wealthiest towns in the country and although the halcyon days of large shipbuilding were long since over, ship and boat repairing was at its zenith. With this in mind application was made, in 1908, for two Graving Docks at Dover to enable major shipping repairs to be carried out at the port. However, the Admiralty negated the request, arguing that such a dock would increase use of the harbour by larger ships, thus causing overcrowding. Further, the exposed position of the dock might render it dangerous in wartime to a ship, which could not get out in case of need. Finally, there was an absence of facilities for workshops and plant for repairs on a large scale.’ The latter, the SECR, DHB and the Council were prepared to pay for.

Western Docks c1910 Wellington Dock in front, behind and to the left Tidal Basin, Granville Dock on the right and Prince of Wales and Admiralty Piers beyond. Dover Museum

The shades of changes to come were seen in July 1911 when tension increased between Germany and Morocco with the Agadir crisis. Germany had sent her gunboat Panther to Agadir, Morocco, supposedly to protect the country’s firms even though the port was closed to non-Moroccan businesses. The Royal Navy’s 2nd Destroyer and 4th Destroyer Flotilla were anchored in Dover awaiting redeployment in Morocco if war broke out, (See the World War I Outbreak story). However, Germany backed down when France offered to retain her Moroccan interests in return for territory in the then French Equatorial Africa now the Republic of Congo. Nonetheless, the Admiralty ordered the Camber, at the Eastern Dockyard, to be deepened and to increase the oil storage facilities there as well as converting Langdon prison, on the Eastern cliffs, into Naval Barracks. Already, both the western and eastern entrances were equipped with boom defences and two 6-inch MK VIIs guns were mounted on the top of the Admiralty Pier Turret.

The summer of 1914 was glorious and Dover’s shipbuilding and boatbuilding with their associated occupations were enjoying the prosperity. But this was all coming to an end by the time that Britain declared War on Germany on Tuesday 4 August 1914. The War took its toll of the number of male Dovorians who were killed or maimed during that time and also on Dover’s economy. The latter was hard hit, not only because the country was at War, because Dover was designated as the military Fortress Dover and as such, harbour and town repairs were not carried out and projects were put on hold. Throughout this time there was rationing and inflation and the tourist industry had ceased. All new ships and boats were built elsewhere and were only repaired in Dover in emergency or were of justifiably necessity.

Following World War I the Dover Harbour Board Marine Engineering department occupied the eastern shed of what is now De Bradelei Wharf shopping complex on Cambridge Road. South Eastern and Chatham Railway – from 1 January 1923 Southern Railway – Marine Department was extended to also occupy the middle shed. At the western end, Cullins’ shipyard – Dover’s only remaining independent shipyard, remained. Albert Edward Cullin (1867-1925) was the son of William and following the War was elected as the Conservative councillor for the Town Ward in the local elections. Shipsmith, Alfred Gutsole remained in business at 4 Commercial Quay and also advertised himself as a blacksmith, while Albert John Partridge (1870-1950) also set up a shipsmith’s business from premises in Market Street. In the mid-1920s Ernest Alfred Tippin (1877-1942), from the Medway, also had a shipsmith’s business in Market Street while Sharp and Enright opened a sailmaking business, next to Cullin’s shipyard on Cambridge Road. Sometime later these premises were let to another sailmaker, J H Clark.

Near to camera is the Dover Stage Hotel. Facing is Cambridge Terrace with Granville Gardens in between. Waterloo Crescent is facing the sea and Wellington Dock is to the right at the rear of Cambridge Terrace. In between the Dock and Waterloo Mansions is Cambridge Road. The photograph was taken from Burlington House in 1974. Dover Museum

Dover was again taken over by the armed forces during World War II and designated Fortress Dover. During this War the town earned the justifiable nickname – Hell Fire Corner – as it was under constant attack from the start of the Battle of Britain on 10 July 1940 to the evening of Tuesday 26 September 1944. For the duration, like much of Dover, Wellington Dock and the surrounding quays and buildings were badly damaged by bombing and shelling. After repairs the three sheds on Cambridge Road were converted into one building. Temporary divisions were installed and then let to various occupants or used as Dover Harbour Board workshops. That is, except for premises at the west end that was still occupied by Cullin’s shipyard. This was under the ownership of Hubert Edward Cullin (1896-1960). In the early 1950’s, boat builders, Dover Yacht Company owned by Bernard Iveson, moved to the west of Cullin’s yard and shipwright Harry Croucher worked from 141 Snargate Street. At the time, shipbuilding was a vital British industry but for Dover, due to the lack of the salient infrastructure, including a large dry dock, this passed the town by.

Hubert Cullin died in 1960 and the shipyard became Cullin’s Engineering until the business closed. Bernard Iveson at Dover Yacht Company was joined by his two sons, Paul and Barry and the business was so successful that besides the shipyard, they had a chandlery at 165-167 Snargate Street. Sadly, Paul died young and eventually publishing company Media Chameleon Limited bought the business name. Following the War, the Dover’s Packet Yard continued to expand but during the privatisation boom it passed into the ownership of A & P Appledore and renamed the Dover Marine Workshops. Eventually, the large Snargate premises closed for the last time on 24 June 1991 and a basic business was transferred to Poulton Close Industrial Estate, Buckland. The demolition of the Snargate premises began the following month and Harry Croucher’s business ceased, possibly at about the same time as the Packet Yard closed.

Following the War, John William Sharp (b1910), who had worked as a plumber for Dover Harbour Board, took control of Sharp & Enright’s and was eventually joined by his son Michael. Later, Michael’s daughter, Sarah Munall née Sharp, joined the firm and now runs the business. In the early 1990s Dover Transport Museum occupied the former shipbuilding sheds on Cambridge Road until the summer of 1996. They were then offered a site owned by Dover Harbour Board, at Willingdon Road, Whitfield in the former Old Park Barracks grounds. There, the Museum continues to thrive and is well worth a visit. Dover Harbour Board along with factory shopping specialists De Bradelei Mill converted part of the former shipbuilding sheds into a factory outlet shopping centre.

The outlet proved successful and the following year the remainder of the buildings were converted and incorporated into the complex and the whole was renamed De Bradelei Wharf. At the west end, the former Cullin’s shipyard was taken over by one of Dover’s philanthropists, Jim Gleeson and turned into a bistro and micro brewery. Taking the name of the Dover’s longest running shipyard, this continues to grow in popularity and nearby, along Cambridge Road, the Fairbairn Hand Cranked Crane can be seen. The maritime engineering firm, Burgess Marine Ltd, with premises on Channel View Rd, was incorporated in January 2006 and operated in the commercial marine, defence and superyacht sectors. Unfortunately, in December 2017 it went into administration and was closed. In February 2018 a new marine engineering and repair company, Mechanica Marine, was launched to fill the gap. Finally, the Port of Dover (formerly Dover Harbour Board), one of the district’s largest employers now offers a bursary scheme for 16-24 year olds in Dover who are undertaking port-related university courses such as Marine Technology with Marine Engineering.

Dover built King George, an 80ton sloop of the Fector Bank Fleet and the fastest sailing ship of her time. Drawn by Lynn Candace Sencicle

It should not be forgotten that Dover built ships, for centuries, were referred to as the ‘Pride of Europe’

Presented: 02 November 2018