Admiralty Pier Gun Turret stands, like a large drum, at the knuckle of Admiralty Pier and Doverhistorian.com was once lucky enough to see the unique and special guns inside. One of the questions frequently asked about the Turret, is why is it part way along the Pier … and easily answered as when it was built, the Admiralty Pier ended there!

Following a Parliamentary Inquiry in 1836, the Admiralty agreed to build two piers to provide a safer harbour – a Harbour of Refuge. After three more inquiries, the decision to combine a Harbour of Refuge and a National Naval Port on the southeast coast of England, the construction of Admiralty Pier began in 1847. On 14 June 1851, the Father Thames, landed 50 passengers at the Pier and five days later the Princess Alice, became the first cross-Channel packet steamer to use the facility when she landed 86 passengers. After that, the Pier was well used by the cross-Channel ferry operators, as it enabled ships to load/unload whatever the state of tide. However, the Pier was not fully completed until 1871.

While the Pier was under construction, there were those in Parliament who were concerned that the Admiralty Pier would also make life easy for any potential invader and a Royal Commission was set up. As part of their inquiries, on 27 August 1853, Sir James Graham (1792-1861), First Lord of the Admiralty, headed a retinue of delegates to Dover on an official visit. They came in the Dover mail packet, Vivid, under the command of Captain Luke Smithett. The ship tied up on Admiralty Pier, the influential officials being met by Dover Mayor, Charles Lamb and the two Dover Members of Parliament, Edward Rice (1790-1878) MP for Dover 1837-1857 and Henry Cadogan – later Viscount Chelsea (1812-1873) MP for Dover 1852-1857. The Admiralty representatives looked around the Pier and also inspected Archcliffe Fort, where the Royal Artillery had recently fixed large guns to protect the envisaged Harbour of Refuge.

The visit was successful and their report was taken into account in a second Royal Commission that was set up to examine the efficiency of the country’s land based fortifications against naval attack. Military engineer, Major William Francis Drummond Jervois, (1821-1897) – later knighted – was appointed Secretary to this Commission, which first sat on 20 August 1859. Their report was published on 7 February 1860 and concerning Dover’s harbour, recommended that, ‘Batteries on the breakwater (Admiralty Pier) will be required, when that work had progressed sufficiently far out to afford the necessary sites.’ When the Pier was completed in 1871, it was agreed that a gun turret would be built at the Pier head.

The design was a Fort, probably with two tiers of guns and on the top of the tiers, three more in cupolas. The building contract for a £20,000 superstructure, signed in September 1871, was given to Henry Lee & Sons of Chiswell Street, London, who had been working on the construction of Admiralty Pier. The Admiralty appointed Dover Harbour Board engineer (DHB) Edward Druce (died 1898) as the engineer in charge. He was already the overall engineer in charge of the building of the Admiralty Pier. To prepare the foundations, Druce used diving bells as he had for the construction of the Pier and work started in January 1872. As part of the foundations, Druce incorporated a projecting apron to secure the base of the structure from being undermined by tidal currents. Within two years, the stonework for the Turret was up to high water level and the substructure was completed by January 1874. The cost was £19,718 4shillings 0pence.

The year before the Admiralty had rethought the type of guns to be used and decided upon one that would pierce the thickest armour plating on ships then available. This led to a change in design to a Turret similar to those erected on the Royal Navy’s iron armour-plated ships and required a 75-ton gun from the Royal Gun Factory. The specifications for the gun stated that it had to have a bore of 14inches but being able to be increased to 15 or 16 inches. Design number W3913 was produced by the Factory’s Superintendent and the gun was estimated to cost £8,000. Approval was given and in September 1875, a gun with a bore of 14½ inches was ready. The specially built barge, Magog, took the gun to Shoeburyness for testing. However, by that time, the Admiralty had changed its mind yet again and decided on two heavier guns of 80-tons each that were ordered and built at Woolwich.

The new design for the Turret was produced by Captain English and was an iron-plated circular rotating structure weighing over 700 tons. It was the only one of its type to be built and within it there were several levels. The Turret’s frame was of wrought iron clad with three layers of 7inches armour with 2-inch layers of iron and wood between them. The upper chamber – 33-feet above sea level – was to house two 80-ton, 16-inch rifled muzzle-loaders with a range of up to 4.3-miles. The magazine was in the basement just above high water mark, and separated from the engine room by a granite wall. This was divided into three sections each containing 50 rounds of Studless Common Shells MkII, and Palliser Shots MkII, complete with gas checks, wedge wads etc. for each gun. Lifts were installed to the upper chamber to enable the guns to be loaded in 2½ minutes.

For the new design, the stonework had to be brought up to quay level with the contract again being given to Henry Lee & Sons. By April 1875, the stone base of the Turret was finished and covered with a temporary roof. Luckily the roof was strong for on Tuesday 24 August 1875, some 200-300 people gathered on and around it to see Captain Matthew Webb (1848-1883) dive off the end of Admiralty Pier. This was the start of the first successful swim across the English Channel to France with Webb taking 21hours 45 minutes to complete his 39mile (64 kilometres) swim. The Webb Memorial can be seen in the Gateway Gardens on Marine Parade.

The Turret revolved on thirty-two wheels and was powered by five steam engines. The engine room was built of solid concrete and was partly below sea level. The machinery servicing the guns was designed by Richard Hodson (1831-1890), Chief Engineer of the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company. One engine ran the guns in and out, and elevated and depressed them. It also worked the ammunition lift and the rammer. The main engine rotated the Turret. An auxiliary engine and a donkey engine supplied two boilers and drove the pump for the ‘Hydro Pneumatic accumulators’, which were used for hosing out the guns. Finally, gas lamps provided lighting.

To lift the guns into place Captain English designed a special shearframe – an ‘A’ frame with the feet or spars that rested on the ground and secured in place by splay and heel tackles. The top of the spars or crutch, were held in place by guy-wires and a block and tackle attached to the crutch that was used as part of the lifting process. Captain English also designed an overhead traveller – a gantry with a travelling crane. Together and using hydraulic jacks, they were to be used to lift and move the guns from the Pier to the top of the Turret. The traveller was designed to be mounted on wooden supports with one end placed on top of the Turret and the other overhanging the quay. Each gun was to be hauled up from the quay using four hydraulic jacks, manually pulled to the other end of the traveller and then lowered into the Turret.

Built on Admiralty Pier by Messrs Tannett, Walker & Co of Leeds under the supervision of Captain English, the shearframe weighed 60tons and cost £3,286, while the traveller weighed 22tons 8hundredweight and cost £782. In August 1881, the naval steamship Panamure brought 110tons of railway iron from the Royal Arsenal Woolwich to test both the shearframe and the overhead traveller. Due to lack of space, it had been decided that muscle power, with a strong derrick, would be used to lift the guns and carriages out of the ship in which they were delivered.

By September, the platforms for the guns were in place and good progress had been made erecting the shearframe by the time the gun carriages arrived. The carriages were designed to transport the heavy guns and to support them when they were fired. They were built of wrought iron, weighed 30tons each and mounted on two sets of six-wheeled bogies. The carriages were lifted from the ship to the Pier and from the Pier to a sufficient elevation before being gradually lowered, with great care into position, within the Turret. Manpower and the derrick was used throughout with the entire operation taking a week.

The first test on the shearframe and traveller took place on 17 October 1881, but one of the parts of the shearframe failed. With the problem fixed a second test was successful. It was discovered that with the use of a large capstan, temporarily installed for the purpose, 60 men could lift 110tons ‘easily’. However, a severe gale hit Dover on 27 November and washed the shearframe, blocks of granite, slings for the 80-ton guns, loose chain, some of the railway iron and an iron trolley weighing about 2-tons, into the sea. The sea also broke through the Turret’s temporary roofing doing considerable damage to the machinery inside with the engine room reported to have floodwater to the depth of 7½feet. The shearframe, washed up near East Cliff , was dragged along the seafront by a large fatigue party. Divers managed to retrieve most of the other articles but not all of the railway iron that included rails on which the trunnion sleigh was to run when moving the guns along the quay.

After test firing, the first of the enormous guns was brought to Dover aboard the Stanley arriving on Sunday 4 December 1881. While repairs to the Turret were taking place, the ship berthed in the Granville Dock. The installation was conducted by Captain Bailey of the Royal Artillery and Major Plunkett of the Royal Engineers under the superintendence of Colonel Inglis and Captain English. On 6 December, the ship was moved round to the side of the Pier and an attempt was made to lift the gun out of the ship. It failed due to the time wasted on the quayside preparing for the lift which meant that that the tide had receded with the result that the chains were too short! A second attempt was made on the Wednesday and a third on Thursday 8 December. This day, the huge gun was lifted out of the Stanley and then lowered onto the trunnion sleigh – a large gun carriage with steel plates along the bottom and mounted on rollers.

On Monday 12 December using man power and rope wound round the specially installed capstan, the trunnion sleigh with the gun on top was hauled onto rails and then to the Turret. Unfortunately, many of the sleepers buckled under the weight and there were insufficient rails due to the number lost in the storm. Eventually, the gun reached the Turret but when it came to lifting, the hydraulic jacks only worked intermittently. Colonel Inglis wrote that ‘when all four jacks were in good order, a rate of lift of 3feet per hour was obtained.’ Further, inclement weather and the sea breaking over the Pier delayed the process even more but eventually the gun was lifted.

When it came to lowering the gun into the Turret, it was found that the opening in the roof was too small so the gun on the trunnion sleigh was lowered in at an angle. Then it was found that the clearance for the trunnion was only ¼inch each side so on the assumption that the tight clearance would prevent the slings coming off the retaining washers were removed. Breaths were held as the gun was lowered, very slowly, but with sighs of relief all round the gun did not fall out of the slings! It was eventually fully installed by 6 January 1882.

The Stanley had arrived in Dover with the second gun on Friday 16 December and stayed in Granville Dock until the gun was finally offloaded. The procedure was as before but with an adequate number of rails, the problem with the jacks dealt with and a wider clearance at the top of the Turret created. The second gun was fully installed by 12 May 1882. Then the massive dome roof, about 1metre thick and comprising of alternative layers of hardwood and iron, was constructed. During this time, work on the guns machinery took place and it was known throughout Dover that the guns were ready for testing.

Letters were written to the Secretary of State for War (1882-1885) – Spencer Compton Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington (1833-1908), from the residents of East Cliff. They complained that due to the dangerous state of the cliffs, when the guns were fired, the cliffs would tumble down. An engineer was engaged to examine the cliffs, reporting they were sound but did suggest that when the test took place the people of Dover should leave their windows open. The test took place on 20 July 1883 and although windows were left open, most of Dover residents gathered on the seafront and Western Heights. At a little after 13.00hrs, the first shot was fired with a 250-pound charge. This was followed by a second shot with 337 pounds of powder and finally, three shots using 450 pounds of gunpowder.

Of the test, it was reported in the Dover Express that, ‘an immense volume of smoke belched forth, and very shortly, at what appeared a mile distant, the projectile struck the water and made three more appearances at a great distance.’ The loud bangs did not start an avalanche at East Cliff and except for two windows in the nearby Admiralty Pier lighthouse, not a window in the town was broken. Nonetheless, the exercise highlighted a number of problems that had to be dealt with.

Following a shipping accident during thick fog in 1885, some of the squared cornered Admiralty Pierhead’s concrete blocks were displaced. The Admiralty Pier head was extended and widened slightly getting rid of the square corners. At the same time the military took the opportunity to make changes to the Turret. As part of the rebuilding a shell store, cartridge store and coal bunker for the Turret was built on the landward side. A passage was cut through to the Turret’s ammunition lift, which then became the main entrance and the original entrance was converted into a defending gallery for riflemen in case of attack. As part of the refurbishment electric lighting was installed, powered by a dynamo driven by its own steam engine.

Admiralty Pier Turret ports, slides and apertures to which the guns were depressed for loading c1873. Dover Museum

On Friday 12 March 1886, another test was carried out when four rounds were fired but again there were problems, most notably the fouling of the guns’ bores. Albeit, of greater interest was the use of compressed air, at 60-65lbs per square inch, as a substitute for steam to the Turret’s engines. The compressed air was supplied through wrought iron pipes from compressors belonging to the Channel Tunnel works, at the foot of Shakespeare Cliff. Following the test, the Defence Committee reported that although there were a few problems the Turret was ready to be handed over to the Royal Artillery.

It was known that the Turret’s weight including the two guns, was 895tons and the whole project had cost £150,000. However, problems remained. The main one being that because of the weight involved, the substructure of the Turret and magazine required strengthening, costing just under a further £40,000. Questions were asked in Parliament, especially as expenditure on military training had been cut to save money. Adding fuel to the anger were developments in the artillery industry, particularly breech-loading long-range guns. It was stated that they made the Turret guns obsolete. Other problems besides the weight were dealt with by a complete lack of urgency, over the next few years.

The guns in the Turret were never to be fired again but in 1895, the Admiralty announced that it was to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy. It was envisaged that the whole of Dover’s bay would be enclosed by an extension of the Admiralty Pier, an Eastern Arm and a Southern Breakwater from the Eastern Arm head to the extended Admiralty Pier head. In January 1898, the Turret was officially declared obsolete, the guns were to be removed and the Turret demolished. This, however was not to take place until the construction of three modern forts had been completed, one on Langdon Cliff and two on Western Heights.

Widening of the Admiralty Pier around the Turret during the building of the Admiralty Harbour. Note the old lighthouse on top of the Turret 18.3.1902. Nick Catford

As the works on the new Admiralty Harbour progressed, the old small lighthouse close to the Turret, which had been repositioned on the roof of the Turret in 1895, was replaced but not demolished. Demolition of the Turret itself, was being considered but at the time, increasing naval expansion was taking place in Germany. The defence of the new Admiralty Harbour became of paramount importance so the Turret stayed and the Pier was widened to accommodate it, though the north east corner was demolished. In the report of Dover’s Defences revised in 1907, it was stated that the Admiralty Pier’s armament was ‘7×12 pr Q.F (quick firing) guns – approved but not mounted.‘ By that time, the Admiralty Pier extension was almost finished and a ‘fort’ was to be built at its head. At the same time, similar fortifications were built on the Southern Breakwater and at the end of the Eastern Arm.

Admiralty Pier during reconstruction showing searchlight emplacements from the harbour side of the Pier – 23.7.1908. Nick Catford

Due to the widening of the Pier, the Turret was on its west side and shortly after the Turret was designated as a battery. It was to have 2x6inch breech-loading guns to cover the approaches from the west mounted on the top so that they fired clear of the Pier’s parapet. Work began in March 1908. The former shell store became the battery’s magazine, with ammunition lifts to each of the guns and two searchlight emplacements were erected nearby being incorporated into the Pier’s parapet. In April 1909 the Turret was designated Pier Turret Battery and two 6-inch breech-loading MK VII*s guns were in place. One of the guns came from the South Front Battery on Western Heights and the other from Woolwich and they were test fired on 16 June. George Prince of Wales, later George V (1910-1936) officially opened the new Admiralty Harbour on 15 October 1909.

The Turret was, on 10 May 1911, again formerly handed over to the Royal Artillery by which time the Royal Engineers had increased the number of latrines and living quarters were made more habitable. The obsolete lighthouse on the top of the Turret was designated as the Battery Control with the battery on the Pier extension under its command. The Battery Control was equipped with, amongst other items, a telephone and a Barr & Stroud range-finder. Searchlights were added to the extension battery and another searchlight, this one on the top of the Turret, in April 1914. Much to the irritation of the captains of the cross Channel ships, the new searchlight faced towards the western entrance and together with the extension search lights ‘blinded them’. The original artillery store and guardroom were, at this time, converted into a bathroom and wash house. From July 1914, the Turret was designated as being manned for War.

The Special Services of the Royal Artillery initially manned the Pier Turret Battery and their main concern, besides the preparation for War, were the large number of Belgian refugees coming across the Channel in all kinds of craft, many not seaworthy. Refugees included the Belgium Queen Elisabeth (1876-1965) and her three children who arrived on a Belgium packet ship that tied up at the Admiralty Pier. At about this time the Port Examination Service came into force and worked from two small steam vessels that were stationed outside the harbour. Their job was to check the credentials of any vessel desiring entry. One of the steamers usually lay off the Turret battery and was alerted, throughout the War, by a cumbersome system that started when a vessel was approaching. The Port War Signal Station telephoned the Fire Command Post who then telephoned the Turret who relayed the message to the Examination Service by megaphone!

Other duties included special detailing, such as when the British Prime Minister (1908 to 1916) – Herbert Asquith (1852-1928) and French Prime Minister (1914-1915) – René Viviani (1863-1925) along with Sir John French (1852-1925) – Commander of the British Expeditionary Force and Lord Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) – Secretary of State for War, dined on board a British cruiser moored at the Admiralty Pier.

On another occasion, the Battery Commander was ordered to give an informal welcome to a foreign steamer of a friendly Power. He was then told that on board were the Directors of Belgium’s National Bank. The ship arrived late at night and the captain, confused by the searchlights scraped against the Admiralty Pier before berthing alongside one of the landing stages. There, wrapped in loose sacking, was unloaded a large amount of gold and securities that were transferred to the Bank of England for safe custody for the duration of the War.

World War I (1914-1918) was declared on 4 August 1914. The Special Services were replaced by the Dover Unit of the Cinque Ports Territorial Force of the Royal Engineers along with regular army units that changed as the War progressed. One of the jobs the men of the battery was to help with was the organisation of troops on Admiralty Pier for embarkation. However, one of their main concerns was the problem of friendly ships being confused by the blaze of the searchlights. This continued throughout the War so the men had to keep a sharp lookout so that the searchlight could be doused when friendly ships were in difficulties due to them. The searchlights were used to search for possible hostile craft and illuminate any sea surface targets as required by the Garrison Artillery and used carbon-arc electrodes. Besides the danger of fire, the carbon rods had to be changed regularly. As this took time, it was important to do it when it was believed there was no hostile shipping around.

During the summer months the Pier Turret Battery operated two watches at night and during the winter, this was increased to three. The routine was that the first shift of the night attended to the overhaul of the searchlights and the last shift the tuning up of the searchlight plant before going off duty. In consequence, there was never any serious breakdown. Subaltern John Mowll, was in charge of the Battery. He later wrote that ‘the strain of continuous watch, largely though night glasses, was apt to become great, and particularly in the early hours of the morning, the seascape immediately before us was apt to be dotted with all sorts of shapes and forms, which loomed up suddenly in the beams of the search lights.’ As the War progressed, as most of the lamps and carbons had been made in Germany shortages became a problem and so the lights were often doused for long periods at a time.

The Pier Turret Battery had their ‘first major encounter’ with the enemy at 05.30hrs on 10 December 1914 when a searchlight reflected off what was believed to be a submarine periscope and they opened fire. The batteries along the Southern Breakwater took up the firing and the ‘periscope’ disappeared. It was reported that four submarines had been seen and that two had sunk and the other two disabled. However, this was later shown to be the product of reporters’ fertile imaginations and that no one was even sure if a periscope had actually been seen!

The officers of the Battery were billeted at Archcliffe Fort. Later in 1916, watch huts were built for them, near the Battery Command post on the top of the Turret. In 1917, another watch hut was built specifically for officers of the Royal Engineers. According to the Batteries Fort Record Book very little happened for the duration of the War, that is, until the final year. A trawler tried to enter the harbour without showing a recognition flag, in April 1918, and was fired upon. Later, in October, two drifters showed the incorrect flag and received similar treatment. Nonetheless, the men who manned Pier Turret Battery were heavily involved in the embarkation of troops going to fight at the Front and those disembarking, particularly the wounded who were taken to Marine Station that had been commandeered for the purpose.

Following the end of the War the Pier Turret Battery establishment was maintained until 1920 when it was reduced to one Non-Commissioned Officer and three men. The two 6inch MKVII* guns were stripped and greased and the breech locks were stored in the Turret along with two 12-pounder guns from the Shoulder of Mutton Battery below the Castle. In 1921, a depression range-finder was mounted on the Turret underneath the Barr & Stroud range-finder. The Battery, until 1938, was kept under ‘care and maintenance’, mainly being used for Territorial Army exercises.

Western part of the harbour circa 1950 but showing the harbour as it would have been during the interwar period. Nick Catford

On 19 July 1921, DHB opened a promenade on the Admiralty Pier and this proved a popular tourist attraction. In preparation, the military obliged by moving the two gun shields for the 6-inch breech-loading MK VII*s, to inside of the Turret’s railings. The gun shields were dragged on well-greased planks using a winch and a 6-to-1 tackle arrangement. At about this time, the Turret itself underwent a major refurbishment using batten and canvas walls, to create a family home for the Battery Sergeant Major. The guardroom became the entrance hall, living room and bedrooms. The artillery store was converted into a kitchen and the store into a washhouse. The fitter’s shop became an office and officers room and a new fitter’s shop with its own forge was built. The flanking gallery was converted into a lamp room and a wartime temporary lean-to was given a new lease of life as a paint shop. In the summer, the Battery Sergeant Major would erect a board outside the Turret giving a history of the guns and an offer to show people around on request!

The British Prime Minister (1937-1940) – Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940) together with French Prime Minister (1938-1940) – Édouard Daladier (1884-1970) met the German Chancellor (1933-1945) – Adolph Hitler (1889-1945) and the Italian Prime Minister (1922-1943) – Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), in Munich during September 1938. This was to discuss the future of the Sudetenland part of northwestern Czechoslovakia. Briefly, at the meeting, Mussolini put forward a plan prepared by the German foreign office, in which Germany would occupy Sudetenland and an international commission would decide on its future. An agreement was reached on 30 September following which Prime Minister Chamberlain flew back to England, waving the declaration and making his infamous statement, ‘Peace For Our Time.’ Shortly after, the 170 (Kent and Sussex) Heavy Battery of the Royal Artillery Territorial Army moved into Admiralty Pier Turret and armaments started arriving.

The 170 (Kent and Sussex) Heavy Battery were subsequently withdrawn but were back again on 3 September 1939 with the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945). Like the previous War, the Command Post was at the Turret and on the Admiralty Pier extension was the second gun emplacement, referred to as the battery out-post (B.O.P.), amongst other names. However, there was an acute lack of accommodation and the men were obliged to sleep in old railway carriages specially brought in. The Battery Sergeant Major and his family were found new quarters and moved out. By the end of 1940, officers’ sleeping quarters and servants quarters had been built on the top of the original guard room and an artillery store, a battery office and store above a new fitter’s shop. A single storey collection of buildings had been erected and consisted of the sergeant’s mess and sleeping quarters, workshop and gun store. On the extension were the men’s quarters including bunks in a tunnel under the adjacent lighthouse, ablutions, latrines and a rest room. Within the Battery perimeter, a two-storey block was built for a Bofors gun crew with the gun mounted on the roof.

From the outset of the War, the harbour was part of Fortress Dover and throughout the War, the officer responsible for co-ordinating all of Dover’s defences be they on land, sea or in the air was the Fortress Commander based at the Castle. Although the town and harbour’s six batteries had their own command posts and plotting rooms, the nerve centre was the Fire Command Post, also at the Castle. The six batteries were the Pier Turret battery on Admiralty Pier, the Eastern Arm battery, two batteries on the Southern Breakwater and one at the Citadel, Western Heights and the other at Langdon Cliffs.

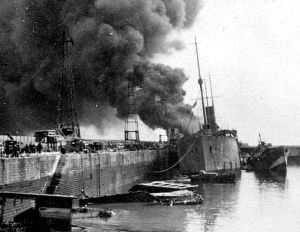

In May 1940, the French and Belgium Channel ports fell to German occupation, which led to Operation Dynamo or the Dunkirk Evacuation, as it is known. This was masterminded by Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945) from his headquarters at the Castle and came into operation on 24 May 1940, when the only escape route to Britain was via Dunkirk. A fleet of 222 British naval vessels and 665 other craft, known later as the ‘Little Ships’, went to the rescue. Many of the soldiers were brought to Dover and were disembarked onto Admiralty Pier, the Prince of Wales Pier and the Eastern Arm. Sometimes the vessels were as many as five abreast. Most of the vessels when they returned to England were battered, some beyond recognition. Some of the vessels were sunk by bombers within sight of the end of Admiralty Pier and it was a sad duty of the men of the Pier Battery to give details.

The men, when they arrived from Dunkirk were exhausted, their clothing in tatters and many were wounded. Soldiers from the Pier Battery were assigned to dealing with the men once they were ashore. Sometimes they provided first aid, at other times it was marshalling the men to waiting railway trains or to ambulances. Many of the rescued men left their weapons on the Pier so another job of the battery was collecting, sorting, and sending them to the appropriate arsenal. Unofficially this was sometimes the Pier battery arsenal! Another distressing jobs assigned to the Pier battery soldiers was helping to recover the identity discs of those who had been killed either on the Dunkirk beaches and brought across by their mates or had been killed while making the crossing. Their job was to list the names for identification purposes. At the other extreme, the most enjoyable part was handing out beer provided by Dover pubs and breweries for the men. At such times, they listened to tales of what had happened in the previous few days of which there were many. Between 26 May and 4 June 1940, 338,226 British and Allied troops were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk.

Following the fall of Dunkirk, General Field Marshal Hermann Goring (1893-1946), Commander of the Luftwaffe, issued instructions for the first phase of a battle, which if successful, would establish air superiority over the Channel to be followed by the invasion of Britain. As a result, on 2 July 1940, attacks on shipping and Channel ports by small groups of bombers with fighter protection commenced. Defences around the country were quickly erected and Pier Turret Battery was strengthened. Both naval and army personnel were stationed at the Pier Turret battery. The Command post already had its own plotting rooms but was equipped with modern technology, as it became available. Between 10 July and 31 October 1940, the frequent and prolonged aerial conflicts came to be known as the Battle of Britain. After the end of October, both in the air and at sea the battles continued until 1945 and this part of Britain became known as Hell Fire Corner.

During the Battle of Britain and after, the searchlights were regularly in use and they were powered by two Ruston and Hornsby diesel engines at Archcliffe Fort. The B.O.P post, a concrete hut at the extreme end of the pier extension had two 12-pounders, installed in 1909 and later another 12-pounder in February 1940, telephones, a lookout slit, latrine and cold running water. What the Turret command post lacked in home comforts was compensated by armaments, including the MKVII* 6inch guns installed in 1909. The harbour was under constant attack and the attacks were without mercy. On 29 July, for instance, all the harbour batteries were dive-bombed by over 120 enemy planes including JU87 dive-bombers and ME 109s. On 18 October a shell fell on the newly built Sergeants’ Mess at the Turret, two men were killed and three seriously injured.

The Pier Battery continued to come under attack from the air, particularly early in the morning when the sun was in the lookouts’ eyes. On 16 December 1941 the B.O.P on the pier extension was bombed and one man wounded. Both the Turret and B.O.P came under attack from the sea though with few casualties. And then there was the weather! On 14 November 1940 when one of the men was going to the B.O.P. from the Turret during stormy weather, he was swept off the Pier and drowned. After that incident, a rope was secured along the edge of the Pier, between the Turret and the B.O.P., for the men to hold on to during rough weather.

During the War, some 69 servicemen were killed and over 100 seriously injured manning the coast batteries and several, stationed at the Pier and Southern Breakwater batteries, were washed over the side and drowned. In order to release troops for the D-Day Landings, on 1 April 1944, Pier Turret became a Home Guard Battery with one officer and eight servicemen. On 18 September 1945, the Admiralty and the War Office handed back to the Harbour Board most of the harbour that they had controlled from 1939. On 30 November 1946, Dover ceased to be a naval base. The last entry into the Pier Turret Battery Record Book was in August 1947 where it was written, ‘ORD B.L. 6″ MKVII* and mtgsMKII were withdrawn and removed to Woolwich C.R. Depot and Swingate Dump, Dover, respectively, by the Armt. Withdrawal Party.’

Over the next few years, many of the structures on Admiralty Pier were demolished and in 1958-59 DHB demolished all the remaining Pier Battery buildings in order to create a walkway. The path was laid on the top of the Turret and opened in 1960 when the old footpath around the Turret was closed. A false roof was put on the remainder of the Turret and raised by three courses of brick to be level with the path. The MK gun positions, still remained and one was converted into a shelter with windows looking out to sea. The other became a raised circular platform with seats on top and a safety rail around it. The Battery Command post-cum lighthouse had been demolished sometime after the War but the base remained. This was made into an artistic ‘feature’ whose aesthetic qualities were lost on most who tried to figure out what its purpose was during the War! The old Turret gun ports were removed and one was replaced with a steel sheet that was capable of being opened but was padlocked. The other was covered with a welded steel sheet. Both of them had four ventilation holes.

At that time it was possible, with permission and under DHB escort, to see the 80-ton guns, their carriages and machinery – albeit rusty – lifts and World War I and II artefacts. Following the Great Storm of 15-16 October 1987 the walkway was closed and it was reported that much of the machinery had been removed due to corrosion. In 1990, this author was lucky enough to enter the Turret but all we were allowed to see were the 80-ton guns and part of the inclined slides that let them descend until the muzzles protruded from the gun ports. Nonetheless, it is a memory not forgotten. In 1996, Cruise Terminal One opened in the former Marine Station and passengers on board the various cruise liners can, from the decks, see the Turret. It can also be seen from the walkway along Admiralty Pier. Listed as Grade II as part of the Admiralty Pier and Associated Structures listing, it is a unique structure, inside of which are the only guns of that type ever to be mounted on land.

One day, perhaps, the Turret will be open to the general public.

- First Published in the Dover Mercury: 12 August 2010

- Revised and Expanded: 14 May 2015