In July 1944, while World War II (1939-1945) was still raging and Dover was still earning the accolade ‘Hell Fire Corner’, Dover Corporation was discussing a master plan for when peace came. Although property damage, due to the constant assault, that was to continue, town was devastated including Dover’s seafront, that comprised of the Esplanade, Waterloo Crescent and Marine Parade. The report only made a cursory reference to these once regal properties and those between the seafront and Townwall Street, such as Cambridge Road, New Bridge, Camden Crescent, Wellesley Road, Marine Place, Douro Place and the long Liverpool Street.

The reason was that the council had taken for granted that the land on which these properties stood belonged to Dover Harbour Board (DHB) and therefore, their responsibility. It is written in the Dover Harbour Charter of 1606, that all reclaimed land belonged to DHB. This is land east of the Boundary Groin (opposite the Swimming Pool) to Shakespeare Beach in the west. Seafront land from the Boundary Groin east and including East Cliff and Athol Terrace, came under the council’s jurisdiction. At that time, the Eastern Dockyard, along with the rest of the harbour, was under the control of the Admiralty. Thus, the report mentioned the loss of an open sea view due to the Admiralty harbour and the Sea Front railway (which eventually ceased at the end of 1964) and the property damage at East Cliff but little more.

In December 1944, the council appointed a new Town Clerk, James Alexander Johnson – known as James A – a brusque Yorkshire tyke with an astute legal brain. He was of the opinion that the laws appertaining to reclaimed land were obsolete. He argued that Dover Borough Council boundary had been redrawn several times since then and all the property occupying reclaimed land sites paid rates to the council including those to the east, such as East Cliff, which the DHB did not ‘claim’ to be theirs. Further, land surrounding Eastern Dockyard, at that time under the jurisdiction the Admiralty that too, when peace returned would be returned to the rightful owners, the Dover Borough Council. Thus, when DHB announced that they were going to repair the war-torn property on what they believed to be their land, Mr Johnson advised the council to refuse permission!

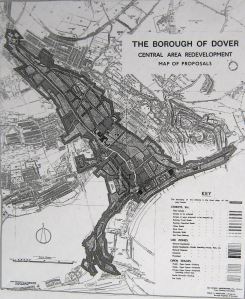

When peace eventually returned, the council sort the help of Town Planner, Professor Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957), to encapsulated their plans. His report was published in January 1946 and land formerly claimed by DHB was included. This, according to the Professor’s report, represented ‘the front door’ to the town and it was envisaged that the existing properties that had suffered war damage would be demolished and replaced by marine gardens. Behind, would be a wide access road to the Eastern Dockyard that would become one of the town’s industrial zones.

The Professor’s Plan went before the Council in February 1947, who having made some modifications and then asked the Government for a Declaration Order. This covered 252 acres of land extending from Buckland Bridge to the Seafront. At the subsequent Public Inquiry the proposals were well argued by James A., who finished by asking for immediate Compulsory Purchase Orders on Seafront properties as well as properties in other parts of the town.

At the Public Inquiry the DHB team did put a forceful argument to repair the properties on land that they claimed to be theirs. However, James A tore the arguments apart and he finished by saying that the rebuilding of the properties was ‘inconsistent with the council’s planning proposals…’ and could not … ‘be regarded as even remotely connected with the statutory functions of Dover Harbour Board.’ Finally, he argued, if DHB could legally show that they had full legal rights of the land on which the properties stood, their plans would be costly to implement. DHB had estimated cost for refurbishment was £38,000 but the Inspector agreed with James A. DHB appealed but this was dismissed.

The council then consulted the eminent Structural Engineer influential in the development and use of reinforced concrete, Dr Oscar Faber (1886-1956). He agreed with the council and Professor Abercrombie saying that, ‘all existing buildings along Dover’s seafront are examples of early 19th century ‘jerry building’, and as such unsound and unsafe so should be demolished and the sites be put to more economic use.’ His report did however, say that Waterloo Crescent should be retained!

With this in mind, the council decided to balance the eastern and central block of Waterloo Crescent with a ‘New York style‘ apartment block of 450 flats. The block would be set approximately 180-feet (244 meters) back from the sea wall and incorporate an access road at the rear. The intervening area between the flats and the seafront road was to be laid out in lawns and gardens, ‘to provide a much-required amenity.’

Dover seafront after the demolition of property and the ground prepared for what became the Gateway Flats. Courtesy of David G Atwood.

Against considerable opposition from DHB and their tenants who still occupied Seafront premises, the council applied for a Declaratory Order to compulsory purchase all the Seafront properties with the exception of the western and central block of Waterloo Crescent. A year later, the eastern block was saved following an appeal by the National Coal Board, who occupied offices there. Using the compulsory purchase orders, the council bought 71 properties and numerous vacant sites from DHB for £52,500. The council then accepted an offer of £4,700 for the right to demolish this property and for the contractor to keep the debris.

The financial proposal for the ‘New York style‘ flats went to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government in1949 and received favourable backing. By October 1951, the number of flats had been reduced to 300 in three blocks each of seven storeys with garages at the rear. The cost was estimated at £½m. The council bought the Grand Hotel for £4,300 and demolished that in the autumn of 1951.

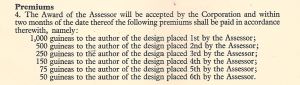

The following June approval was given for the flats but with the proviso that the design came out of a national architectural competition. The remit was for 300 flats in a continuous block of such great height that they gave living room and at least one bedroom of every flat a southeasterly orientation and a frontal view of the sea. The submitted designs were to be judged by architect Arthur W Kenyon (1885-1969) who specialised in Town Planning. There were to be six prizes with the rewards ranging between 1,000guineas (£1,050) to 50 guineas (£52.50p)

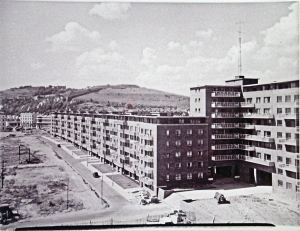

Gateway Flats – Winning design by Roger K Pullen and Kenneth Dalglish October 1953. Thanks to Richard Barwick

In September 1953 it was announced that Roger K Pullen and Kenneth Dalglish who had won and was to receive 100guineas (£105) with a design that provided for 301 flats. The difference in the prize money given and that promised, immediately called the competition into question. The council replied that the remainer of the prize money would be offset against the final fees paid to the architects. The other prizes were scaled down accordingly and eventually thoose architects accepted the reduced prize money.

The proposal was for a long narrow nine-story block of flats, with staircase towers at intervals and projecting lift shafts on the roofline. Running parallel to Marine Parade the apartments consisted of a curved 15-storey block at the eastern end and the cost was estimated at £773,573. The Royal Fine Arts Commission (RFAC) disapproved of the plan saying that the design had three clear defects. They were:

i. The flats created a barrier, which would cut Dover town off from the seafront.

ii. The height of the flats would not only dwarf its surrounding area but would throw out of balance the view of Dover from the sea, which included the harbour, cliffs and Castle. Further, the Castle especially would suffer severely from so overpowering neighbour.

iii. The architecture showed a lack of sensitivity in the handling of mass and detail worthy of so fine situation.

Kent County Council (KCC), whose approval was required in those days, agreed with the Commission and the scheme was rejected. In June 1954, after a number of debates in which the RFAC and KCC were severely criticised for not providing an alternative suitable scheme, Pullen‘s design was amended. The proposal was for 12-storeys, in a gentle curve with a ‘leg’ at the western end overlooking Granville Gardens. The lift shafts were eliminated and replaced by Pent-houses that were accessed by stairs. The number of flats was reduced to 283.

This new proposed design was given approval by architects Arthur Kenyon and Geoffrey Jellicoe, (1900-1996). Jellicoe was later knighted for his work on landscape gardening but at the time he was the consultant architect to KCC. However, KCC did not entirely agree with the eminent architects but eventually gave tacit approval as long as the number of storeys was reduced to nine.

Dover council submitted an amended design to the Minister of Housing for a loan. This showed a curved block of 10-storey flats with garages on the ground floor and a 7-storey block parallel to Marine Parade and Granville gardens. In December 1954, the government sanctioned the loan if the height was reduced by two storeys throughout, giving 223 flats. The estimated cost had risen to £870,000 but the lack of money and shortage of building materials resulted in the Seafront remaining derelict.

Nevertheless, the idea of the flats did not go away and the council reconsidered the plans in March 1956. However, at the meeting, Mayor Sydney Kingsland (Conservative) warned that if flats went ahead, the annual cost could exceed a shilling (5p) on everyone’s rates. Therefore, an alternative proposal of creating a grassed open space to tie in with Granville Gardens was agreed. Then, during the summer the government granted £600,000 towards the flats and the new Conservative Mayor, John (Jack) Williams, voted with the opposition for the development to go ahead. The plans were submitted to KCC who gave approval in August 1956.

Tenders were invited and after a three-hour debate the council accepted the offer of £1,044,613 from Rush and Tompkins of Sidcup, Kent, the lowest of 12 applicants. By this time, thirteen years had elapsed from when the notion of a large apartment block on the Seafront was first proposed. Albeit, the development was new and exciting and one of the many novelties of the scheme was the balconies. These were cast on-site, which enabled each flat to be completed in two and a half days. Within a year the first flat was completed.

Albeit, it was not all plain sailing for the council thereafter, one of their major problems was the residents of the property on which compulsory purchase orders had been served. Many of the residents refused to move so the council, used ‘heavy tactics’ to get them evicted. Typical of the ‘heavy tactics’ was recounted by the family of Mrs Gibbs, the 84-year-old owner of Marine Garage on Townwall Street. In 1959 the County Court heard that her property had been ‘utterly devastated’ by the council in order to acquire it by compulsory purchase. Of course, the council’s legal department denied this even though evidence was to the contrary.

In February 1958, the council, announced the winner of a competition to name their edifice. With more than fifty suggestions they chose to call the new flats ‘The Gateway’. Within a week of issuing application forms for tenancies, 153 had been returned completed. By the end of June 1958, the number of applications had exceeded the number of flats by 40 with approximately half of the applicants coming from outside of Dover. A council sub-committee was appointed and decided that 75 per cent of the smaller flats should be allocated to local residents or those working in Dover. In the case of larger flats although no percentage was fixed preference was given, all things being equal, to local people.

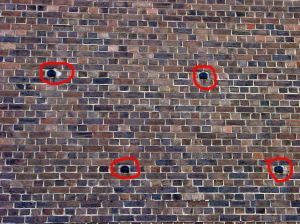

Lukey’s Gin bottles used instead of tile, adjacent to the Townwall Street entrance opposite Swimming Pool. Alan Sencicle 2009

Besides the balconies, mentioned above, other ‘novel’ features of the Gateway included an ‘entrance’ from Townwall Street to the seafront gardens that was designed to ‘entice visitors’ – but no longer. The gardens, that at the time included a long low rockery, an illuminated fountain, and a pool with a footbridge spanning a cascading streams from the fountain. At the west end, facing Granville Gardens across Wellesley Road, was (and still is) a multi-coloured mosaic panel depicting the Channel coastlines. On the Townwall Street side, near to the entrance opposite the Swimming Baths, due to a shortage of matching green tiles dark green gin bottles, provided by Lukeys, were used instead – these can still be seen!

The Gateway, with 221 flats all with sea views, was eventually completed in October 1959 at a cost £1m. When ready for occupation, former Mayor, Cllr. Jack Williams, who had voted with the opposition for the proposal, was one of the first to move in! The last of the flats was handed over in January 1960. A Government subsidy of £10,416 was given and the contribution from the rates was £8,321 – 4pence on every property rated in the town.

The flats had hardly been occupied when a problem manifested itself. The council, in 1961, had banned caravans from public carparks due to the occupants, for the most part awaiting ferries or returning from the Continent, doing their laundry, ablutions etc. Caravanners looking for somewhere else to park on the way to Eastern Docks, found the Seafront and the gardens in front of the Gateway.

There they camped utilising the gardens for recreational purposes and hanging out washing. The drains were used for dumping the contents of chemical toilets and the litterbins for household rubbish. Within a couple of years, tourists found the seafront an ideal place to spend their holidays and when ferries started to take lorries, lorry drivers showed a tendency to park there for a night or two. The problem was, and still is, quickly dealt with by the authorities.

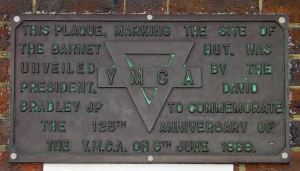

YMCA 125th anniversay plaque former site of the Barnet Hut, Gateway garages Townwall Street 6 June 1969

Before World War II the YMCA Barnet Hut occupied the site on which the garages of the Gateway Flats were built. The Hut succumbed to severe shelling on Sunday 20 October 1940 and never opened again. 6 June 1969 saw the 125th Anniversary of the YMCA and a plaque was unveiled on the site of the Barnet Hut and can still be seen.

Originally, the flats were owned by Dover Corporation and let to residents but following the 1974 Local Government reorganisation, they became the property of Dover District Council (DDC). With the introduction of the 1980 Housing Act – Right to Buy, some residents bought their flats at a discount rate reflecting the rents that they had already paid.

By May 1987, the number of flats were in private ownership were sufficient for DDC to proposed disposing of the remainder to a Housing Co-operative or Housing Association, but this was rejected by the residents. Since then most of the flats have been individually sold and in May 2008, it was announced that the freehold of the Gateway was to be transferred to the Gateway Marine Parade (Dover) Ltd.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury 07 August 2008