The World’s earliest known sea going craft – the Bronze Age Boat in its own special gallery at the Dover Museum. Dover Museum

The earliest known sea-going craft in the world is the Bronze Age Boat kept at Dover Museum. The Bronze Age period is usually given as between circa 2,100BC to 700BC and this boat was built about 1,500 BC. It took goods and/or people across the Channel – the Dover Passage. When Julius Caesar (c100BC-44BC) arrived on the British shores in 55BC, Dover was considered the best place to land as it was perceived as the only sheltered haven on the south-east coast. However, the resident Britons quickly made their presence felt and so the Romans turned east and landed at Walmer. Albeit, the Romans came back in the summer of AD43 with a large force and conquered Briton as far north as the Hadrian’s Wall. They stayed for five centuries during which they used Dover as a base, building light beacons or pharos on the eastern and western heights in order to light the way into the River Dour. The pharos on the Eastern heights still survives.

During the Roman occupation of Dover the River Dour estuary changed, creating two streams, one running west and the other east. The eastern stream, under eastern cliffs, was the most direct course to the sea and here the Eastbrook harbour was formed. The Saxons (c450AD and 1066) followed the Romans and it was during this time that Royal Decrees referred to ships carrying royal mail between Dover and the French port of Wissant. During the days of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) Dover was one of the five ports and two antient towns that made up the Confederation of the Cinque Ports. In return for a number of privileges they were obliged to supply the monarch with 57 ships a year, of which Dover supplied 20 ships for 15 days with 21 men for each vessel. This obligation was the forerunner of the Royal Navy.

William I (1066-1087) invaded England in 1066 and in the Domesday Book of 1086, it is recorded that the King’s messengers, riding on horseback, paid 2pence in summer and 3pence in winter for their passage across the Channel. During the medieval period, England had strong ties, not always friendly, with France and in 1227, Henry III (1216-1272) conferred on Dover the monopoly of the cross-Channel traffic to Wissant in France. The mariners of Dover became prosperous but also arrogant such that from 1323, a Royal Directive was issued compelling the fellowship of Dover mariners to make fair charges and to take regular turns. Then, in 1343, another Royal Ordinance compelled the fellowship to pay a certain proportion of their profits into the Common Chest of Dover Corporation to be used for the upkeep of the harbour. In 1381 a Royal Charter was issued ordering the passage to change from Wissant to the newly formed port of Calais.

Throughout this time, the Dover mariners in their small ships were well used in making the Passage – crossing the Strait of Dover with goods and/or passengers. They carried Royalty, the Royal court, Royal messages, envoys and armed forces. However, between 1300 and 1500 there was a movement in the land mass that triggered a phenomenon called the Eastward Drift – the tide sweeping round Shakespeare Cliff and depositing masses of pebbles at the eastern end of the Bay. Then a massive cliff fall rendered the Eastbrook harbour useless and the lucrative business of the passage went to Sandwich. John Clark, the Master of the Maison Dieu, petitioned Henry VII (1485-1509) for a grant to build a small harbour on the western side of Dover Bay.

Following the move the passage industry eventually recovered by which time the Dover shipbuilders had developed small sloop rigged craft of about 40-tons. A century later, the major passage between England and France was from Dover and the passage ships that specialised in taking pacquettes – Royal messages etc. – would leave Dover or the French port on the high tide following the arrival of the pacquettes. They became known as pacquette boats and finally packets. Over time, the Dover shipbuilders developed increasingly faster ships and by 1624, there was a well-organised packet service to and from Wissant, Calais, Boulogne and Dieppe.

Although fast, the packets were frequently beset by Dunkirkers – the name given to the Barbary Corsairs who had settled around the estuary of the River Aa that flows into the sea at Gravelines in northern France between Calais and Dunkirk. During the reign of Charles I (1625-1649) Dunkirkers captured a Packet-boat soon after it had left the French coast for England. On board, so the story goes, were three buxom nurses from Normandy, a midwife, dancing teacher, eleven nuns and a gentleman only 18inches tall. He was in fact the poet Sir Jeffery Hudson (1619-circa 1682), who wrote under the thinly disguised nom de plume of Microphilus and was part of the Court of Henrietta of France (1609-1669), wife of King Charles. Sir Jeffrey had accompanied the Queen to England on her marriage to Charles and as she was, by this time, expecting a baby he was escorting the nurses who were to attend the Queen during her confinement. Apparently, Sir Jeffrey, by beguilement and fabrication, saved the ship and the Queen’s nurses from being taken hostage!

Having written the book Discourse on Piracy, which became the recognised manual for the suppression of the illicit occupation, Henry Mainwaring (1587/8-1653) was appointed to try to solve the problem. He was a well-known buccaneer who had turned gamekeeper and was so successful at dealing with the pirates that he was knighted. He was also appointed a Lieutenant of Dover Castle, the Deputy Warden of the Cinque Ports and was elected to Parliament as Dover’s MP!

The cost to the travelling public and the increasing frequency of the loss of official despatches on packets became a justified concern. James I (1603-1625) in 1619, appointed Matthew de Quester as the government’s postmaster to deal with the problems. Officially, his job was to supervise the carriage of letters to foreign parts out of the monarch’s domains between Dover to the Continent. However, Quester made little difference to the service other than effectively introducing a tax – much of which he may well have pocketed – on merchandize. Both the merchants and the packet travelling public complained.

In March 1633, Thomas Witherings, a London merchant, was appointed as one of two postmasters to administer foreign mails and the Dover and French packet service. At the time, messengers on horseback delivered the official mail and, in the case of important mail, the official messengers carried it to the recipient in Europe. Otherwise, mail was put in sacks for the Channel crossing and then given to a second set of official messengers, on the Continent, for delivery to the recipients. As the packet ships tended to drop anchor in the Bay, boatmen were paid £2 to take the mail and official messengers and the horses to the packet ships that would then convey them across the Channel. London merchants had their own messengers and used either packet or passage ships.

Due to the sporadic Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652-1674), the packet boat owners and the men who manned them became exposed to a new danger, that of Dutch privateers who infested the busy Dover Strait. Privateering was a legalised form of piracy that was introduced in England during the reign of Henry III, (1216-1272). Ship owners were granted commissions to seize the king’s enemies ships at sea in return for splitting the proceeds with the Crown. The commissions limited the activity of the privateer to a specific locality and to hostile nations. During the reign of Edward III (1327-1377), the commissions were formalised with Letters of Marque. In order to avoid Dutch ships that held Letters of Marque, the Dover packets could be escorted by large frigates or other armed vessels but they had to be paid for by the Packet Farmer.

The 1657 Postage of England, Scotland and Ireland Settlement Act, enacted the position of Postmaster General and following the Restoration in 1660, the Post Office packet service was Farmed by wealthy individuals. They bought a 10-year lease which gave them authority to charge for mail carried on the packet boats. Out of the revenue the Farmer earned, he paid a percentage to the Crown, hired the packet boats with crew and shore staff that was headed by the Dover postmaster who arranged for saddle horses to carry the mails by six stages to London. Daniel O’Neill (c1612-1664) held the position of Postmaster General in 1663-64 and he gave T. Tremen junior the authority to open a combined Post and Packet Office in Dover. This was at the Customs House in Snargate Street.

Packet ships operated three times a week. On Monday’s packets went to Calais and either Nieupoort or Ostend and on Thursday’s they went to Calais and Friday to Nieupoort or Ostend. There was an established rate for the carriage of letters and this service was to last, except in times of war, until 1744. Between 1672 and 1677, the Dover packet contracts were managed by a Colonel Roger Whitley (1618-1697) who although he used his position to feather his own nest, organised a highly efficient packet service on behalf of the Farmers. Whitley’s efficiency included copies of the correspondence with the Farmers, which were filed in the apparently now missing Dover Letter Book.

Customs House built 1666 demolished March 1821 replaced by John Minet Fector Bank in 1821. Dover Museum

During Whitley’s time, the Dover passage service was worked by four packets and they carried Letters of Protection, which meant that any privateer would be in trouble from his own country if they boarded the one without invite. John Lambert, in 1673, was the master of one of the packets out of Dover but lost his life at sea that year. Dover’s first post office was established in 1673 within the new Customs House on Customs House Quay. The Head of Customs, Mr Houseman, was also the manager of the Dover’s Letter Office, and handled local letters. Under him were Mr Rouse – the postmaster who arranged the saddle horses and there was also the Clerk of the Passage, an early form of immigration officer. The Farmers were Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington (1618-1685) who was the Postmaster General from 1667-1685 and Sir John Berkeley, Baron Berkeley of Stratton (1607-1678).

Charles II (1641-1685) expressly laid down by a Statute that the Packet-boats must not carry parcels or any other freight. Although illegal it was openly flouted even by the government and Whitley was well aware of what as going on and in one of his reports stated that ‘it was coevil with the Packet service itself.’ Unofficially, they only way he could deal with the problem was to ensure that the Clerk of the Passage must satisfy himself that no Packet carried so large a quantity of goods or stowed them in such a manner as to put the ship out of trim. Many of the goods were merely legitimate covers of smuggled contents.

At the time of Whitley, John Carlisle was Clerk of the Passage (see Stokes Dynasty). He was a Dover Jurat who also owned one of the packets. The other packet owners were Richard Hills, Walter Finnis and Ambrose Williams. In 1674, Francis Bastinck was appointed Clerk of the Passage and four years later was appointed Dover’s Postmaster. The Farmer was James Duke of York (later King James II 1685–1688) who complained to the Privy Council that the Dover mails were too slow. A Mr Sawtell was sent to investigate and Mr Rouse, the postmaster, was told that he was ‘to haste in his duties … the Dover letters were expected at Court every Sunday.’ Around 1678 the Dover Letter Office moved to Strond Street and remained in the Pier District until 1893 when it moved into purpose built premises on King Street. During the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) of France, the word malle, entered the English language as mail. Malle were the bags slung across post horses backs in which letters were carried.

The continued improvements in the designs and building of ships by Dover shipbuilders meant that in the 18th century they had the reputation of being the most sturdy and swiftest sailing ships in Europe. Indeed, Dover’s packets were so highly thought of that orders for Dover built ships craft flowed into the town from the Admiralty, domestic and foreign buyers. Although the Custom Farmers hired packet ships some were individually licensed by the Post Office, individual ship owners were not paid to carry mail. Their profits came from carrying passengers and freight but because of the reputation of the service they provided, the individual owners enjoyed a long running boom and pushed the Custom Farmers out of the market.

Possibly, because the local passage shipowners were making good profits, by the mid-18th century the Post Office introduced greater control that included a share of the proceeds from passenger and freight traffic. Ships, by this time, had increased in size with a crew of nine, except during wartime when the number of men increased. During those times, the packet ships were allowed to carry armaments for use against privateers. There were also changes taking place on the Continent and by February 1744, the regular mail service to Nieupoort had ceased with all Flanders (Belgium) mail going to Ostend. This left Dover on Tuesdays and Fridays and the Post Office changed the Calais packets to Tuesdays and Fridays in April 1763.

However, the relationship between France and England was far from cordial. In January 1773, according to a story cited by Alec Hasenson (History of Dover Harbour. Aurum Special Publications 1980 pp149), ‘the Packet Express sailed from Dover to Calais with mails, and their being a heavy sea, Mr Pascall, the mate of the Union Packet, then in Calais, thinking the Express could not enter the port, came out in a small boat, rowed by seven Frenchmen, to exchange mails at sea. The boat was upset, and the seven Frenchmen drowned. Pascall contrived to get on the bottom of the capsized boat, but because the French were all drowned, the French soldiers would not allow a boat to go out and rescue Pascall, who was drowned within hail of hundreds of spectators.’

During the American War of Independence the Fector’s were forced to sell their ships. This poster was produced by the purchaser Flanegan Vercoustre. Dover Museum

The situation deteriorated even further during the American War of Independence (1776-1783), due to the danger from French privateers. They, apparently, took no notice of the Letters of Protection and the packets ceased making the crossing. The Dover packet ship owners such as the Minet/Fector’s were forced to sell their ships and instead use small but fast boats with shallow draughts and used ‘safe’ Continental natural harbours. Following the War, four Dover packets operated, making the crossing every Wednesday and Saturday with mails for Calais and Ostend.

This encouraged the growth of the smuggling industry a practice that became so flagrant that there was a public outcry and investigations were undertaken. It was found that in Dover the game of eluding the revenue laws were played to perfection and with even more zest in the West Country. Admiralty Records show, that Customs Officers more than once complained of the obstruction they met with when the Revenue men went on board Dover Packets to carry out routine examination.

By this time two large shipping companies had developed in Dover and they were owned by the Minet/Fector and the Latham/Rice banking/shipping families. They also owned all the packet licences and had fleets of ships that were fast and were used interchangeably as packet and passage vessels. By the time of the French Revolution in 1788, there were five Post Office packet licences for Dover ships and thirty vessels sailing between Dover and the Continent and both families were heavily involved in smuggling.

Calais passengers preparing to board a Packet boat c1803 by Joseph Mallard Turner M Turner. LS print

Following the outset of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) the base for the Channel packets moved to Harwich and passenger and mail services out of Dover were officially suspended. Except for Fector ships, packets were redeployed either as cargo vessels or commandeered by the Royal Navy as warships. As the Fector bank held a large percentage of the Vercoustre company based in Ostend, their ships sailed under the neutral Belgian flag and they were immune from attack. In fact, their advertisement asserted that they sailed ‘free from molestation from ships and privateers of the Powers at War’. In 1799 a regular stagecoach between Dover and London was introduced and shortly after a weekly mail coach.

Under an agreement between the French and British Governments an Order in Council had exempted the Post Office Sailing Packets and Byes from the general embargo on shipping – a Bye was a vessel hired temporarily for the postal service. Thus the Dover packet service had been officially reinstated but was administered by the Admiralty. In 1798 the Dover packet, Despatch, commanded by Captain John Osborne was summoned to surrender by a French privateer and his ship was seized despite various protests. Osborne and his crew were made prisoners-of-war and the Despatch was taken to Dunkirk where it was declared a ‘prize.’ A few weeks later Captain Osborn was exchanged for a French officer prisoner and returned to Dover, but his crew were kept in prison, with one remaining there for three years before he was exchanged. In September 1798 Captain Osbourne was carrying two of the King’s messengers on the Despatch and they were taken ashore at Calais in one of the ship’s rowboats. What happened next was described by diarist Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819), who wrote that on going ashore the two Messengers ‘were drowned and also one of the sailors, the boat was over run with waves.’ (14 September 1798).

Privateering continued in the Channel and the Wars continued on the Continent. However, in the early hours of 14 February 1814, the weather was cold and the skies clear when there was a knock on the door of the Ship Hotel, on Custom House Quay. The proprietor, Benjamin Worthington, opened the door to a man in rich military dress who presented himself as Lieutenant-Colonel du Bourg, aide-de-camp to General Cathcart (1755-1843). The officer was wet from the knees down and said that he had just disembarked from a boat that had berthed on the beach. He went on to say, in hushed tones, that he was a courier bearing the important news that, ‘Napoleon Bonaparte had been slain in battle, the allies are in Paris and Peace is certain.’ He finished by asking Mr Worthington not to say anything to anyone about this.

Worthington gave the man a dry pair of pants and a hot meal and bid his servants to ensure that the officer was looked after. The officer told each servant the tale and swore them to secrecy. He then left the hotel, ‘in a post-chaise and four for the Metropolis.’ By that evening what the officer had told a few people Dover to keep secret had become common knowledge in London. The following morning anyone with spare cash in the City hurried to the Stock Exchange to buy government consols. By the afternoon the scene there was, by all accounts, wildly exciting!

At number 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister, Robert Jenkinson, Earl of Liverpool (1770-1828), was having doubts. The news had not been followed by any details of Napoleon Bonaparte’s (1769-1821) defeat – nor had any news come by the shutter telegraph system from the Deal Time Ball Tower – the Time Ball was the terminus of the 12-station line between Deal and the Admiralty in London. The Prime Minister’s concerns were well founded for two weeks before Admiral Thomas Cochrane (1775-1860) and some friends had bought consols to the value of £826,000. On 15 February 1814, they sold them for a handsome profit to the eager buyers. For his part in the supposed fraud, Admiral Cochrane received a year’s sentence, fined £1,000 and pilloried. Later his conviction was overturned.

Following the abdication of Napoleon in April 1814, a Peace Treaty was signed and everyone thought that the wars were over. However, on 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from imprisonment on the island of Elba, in the Mediterranean, and quickly reassembled his Grand Army. Determined to regain his supremacy Napoleon prepared for battle and Dover became a hive of activity as troops embarked for Holland.

On the Continent, the events were going Napoleon’s way and by 15 June 1815, he was advancing towards Brussels. On the London Stock Exchange, the price of government consols fell to an all time low. The next morning Napoleon’s forces attacked the Prussians, driving them back and splitting the allied defence. He next attacked the British, under the command of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852). Wellington withdrew to a ridge across the Brussels road near the village of Waterloo and the imminent British defeat was telegraphed, via the Timeball Tower, to London. The bottom fell out of the government consols market.

The morning of 18 June, Napoleon and Wellington faced each other across the battlefield at Waterloo. The battle lasted nine hours and was one of the bloodiest in history. It was said that Nathan Rothschild (1777-1836), whose friends included the Fector and the Latham/Rice families, promised prizes to the first packet to bring news of the battle outcome. One of Rothschild’s agents, Rothworth, obtained a copy of the Dutch Gazette, fresh from the printers with the headlines saying that the Duke of Wellington had defeated Napoleon.

Rothworth travelled from Ostend, on the Latham/Rice packet British Fair and on landing went straight to London. He entered the city on 20 June and immediately reported to Rothschild who, in turn, conveyed the news to the Prime Minister. Lord Liverpool, concerned that it was yet another swindle, refused to accept the news until it was confirmed via the Timeball Tower. Rothschild, together with friends, including the Lathams, Sarah Rice and John Minet Fector went to the Stock Exchange. There, they sold a large amount of government consols at the depressed price to their own representatives. The whisper was that ‘Rothchild knows’ and others sold theirs too – to the same representatives of Rothchild, Lathams, Rice and Fector! When the news broke of Wellington’s success, Dover’s two banking families, along with Rothschild and the representatives, had made a fortune!

The packet service was officially resumed on 10 October 1815, and the administration was immediately taken out of hands of the Fector and Latham/Rice families. Sloops of 60 to 70 tons were brought to Dover and the crossings were dependent not only on the ships but the wind and tide. If the wind was favourable and the sea calm, the crossing could take three hours to Calais and to Ostend in seven. However, if unfavourable, it was considerably longer as the ships were forced to tack, traversing the channel in a zigzag fashion that doubled or even trebled the distance. Passengers suffered great discomfort and on arrival from the Continent to quote one contemporary writer, ‘…porters of all ages seized your baggage as soon as you had arrived at Dover and conducted you, whether you liked it or not, to the hotel opposite – the Royal George – the landing stage from where the mail-coaches left for London. In the hotel you found an enormous buffet laden with veritable mountains of food; roast beef, hot and cold roast chicken, turkey stuffed with truffles, York ham and pies of every description. Magnificent cut glass decanters and glittering bottles scintillated among the plates of food. All this was rather tempting, but costly to the traveller, who only had to reach for a leg of chicken or a glass of sherry. It was asking too much not to give way to temptation, especially if he had had nothing to eat for twelve or fifteen hours or, more …’

Once on the coach, the passenger was faced with a long, cold and uncomfortable ride to London 75 miles away. This would take about six hours if the coach were non-stop and much longer if it stopped to enable the passengers to take refreshments or to stay the night. The luggage followed, piled high on other coaches or on open, but cheaper wagons, which travelled at much slower speed and frequently stopped the night at taverns enroute. Both were called ’slow coaches’ and thus originated the description, still applied to anyone who is slow moving.

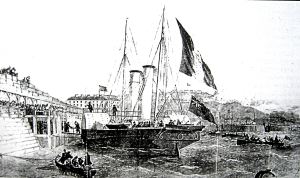

On Friday 15 June 1820 the first paddle steam packet, Rob Roy, was introduced to the Dover-Calais passage. Taking 4½hrs to cross the Strait, the 88-ton ship was built by Denny of Dumbarton with 33 horsepower engines by Daniel Napier. The French government, attracted by the idea of steam, purchased Rob Roy, gave her the name of Henri Quatre. She subsequently worked the Calais-Dover run. George III died on 29 January 1820 and his estranged Queen, Caroline, was brought to England in the Prince Leopold, a Fector Packet ship under Master R Rogers. The Queen arrived on 5 June 1820 and was given a tumultuous welcome plus a royal salute from the commandant of the garrison and a guard of honour!

In 1821 the government gave the packet service to the Post Office and they introduced the Arrow and the Dasher as their first cross-Channel steam packets. They were both wooden paddle steamers with the 149 gross ton Arrow being built by William Elias Evans of Rotherhithe and the 130 gross ton Dasher by W Paterson, also of Rotherhithe. In 1824, the Post Office acquired the 110 gross ton 83-foot Spitfire wooden paddle steamer with 40 horse-power engines built by Graham’s of Harwich and the wooden paddle steamer Fury also built by Graham’s of Harwich. The Post Office sailing ships at the time were the Aukland, Eclipse, Chichester, King George II and the Lord Duncan. Dover shipbuilders built three. On 1 October 1822, the Monarch, a 100 gross ton wooden paddle steamer built by James Duke of Dover and engined by Maudsley, Sons & Field, London was launched. Working the Dover-Boulogne route on 30 April 1824, due to catastrophic engine failure between Boulogne and Dover, the Monarch was withdrawn from service and sold.

Because the Post Office steam packets were not so vulnerable to wind conditions as the sailing ships they were preferred by passengers to the passage sailing ships. On 9 August 1833, the Post Office introduced a daily service, weather permitting, except on Sundays, between Dover and Calais. During bad weather Calais harbour was neither easy to enter or exit and Dover impossible even for steam packets. On such occasions, all ships would run to the Downs off Deal, until the weather abated. Albeit, in 1834, Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) made the crossing from France to England having travelled from Rome and praised, in his biography, of the ‘up-to-date advantage of a well fitted steam packet’.

On 5 February 1834, the Arrow with Captain Luke Smithett in command made the crossing from Dover to Ostend, in 5hours 45 minutes, the fastest passage on record at that time. However, Henshaw Latham of the Latham shipping/banking family was not impressed. He held a number of consulates that included the American, Russian, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Sicilian and most of the German States and wrote, ‘Holding eleven consular appointments we have constant applications from maimed, invalid, discharged seamen; a number of vagabonds passing themselves as such. Whilst there were private Packets, we had comparatively no difficulty, but now that the Post Office have monopolised the Passage. It is a sad cause of Annoyance … (as there is) trouble to get Reimbursement of your actual expenses.’

This probably stemmed from the fact that the steam packets were proving costly for the Post Office and they wanted out. A number of private concerns made offers for the Dover packet service, but all were turned down. Instead, a Commission of Inquiry headed by Captain George Evans was set up in May 1836, to investigate. It was found that the cost of operating, maintenance and repair of the ships for the four years to May 1836 was £273,018. In the same years, the packets had made a loss of, on average, £38,739 a year.

At Dover, it was noted that the packets left early in the morning so that the mail could be taken on a Paris train that arrived in the French capital late morning. However, potential passengers found the time leaving Dover far too early nonetheless, there was a growing interest to travel on passage ships. The prospective loss to the Post Office was estimated as £4,000 for the previous year. It was also reported that at Dover, ‘the accounts were not examined with a view to ascertain whether the stores charged have been actually supplied, nor are any observations made on the prices. The bills are not certified by the commanders; and the agent acknowledges that the only check he has is his dependence on the honesty of the tradesman not to charge far more than has actually been delivered.’

All the necessary arrangements were made to transfer the national packet service to the Admiralty in December 1836 with the Post Office regulating the times of departure.

On 21 October 1837, Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (1774-1850), arrived at Worthington’s Hotel on Packet Boat quay, at 18.00hours to meet the Duchess, Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel (1797-1889). The following morning they left on the Ferret under Captain John Hamilton (1765-1758), whom the Duke had particularly requested. Captain Hamilton had been in Calais and had to come back to Dover specifically to meet the Duke’s request. He escorted the Royal party across the Channel and they stayed in the state apartments at a hotel in the French town.

The lack of a direct rail service to Dover was having a detrimental effect on both packet and passage ships, as passengers were increasingly switching to travel via Folkestone to France. Despite this severe handicap the Admiralty packet industry developed into a very efficient organisation and many new steamships were built such as:

The Widgeon, a wooden paddle steamer built by Sir William Symonds at Chatham, engined by Messrs Seaward & Capel of London and tonnage 164 gross. She came straight from the shipyard on 25 October 1837, captained by M J Hamilton. From 1847, she became a survey ship for the Royal Navy. In the third week of August 1850 the Widgeon, made several crossings of the Channel laying flagged buoys that marked the course of the first cross Channel telegraph cable

Dover an iron paddle steamer designed and built by John Laird of North Birkenhead, engined by Messrs Fawcett & Co and was 224 burthen (an archaic tonnage of a ship based on the number of tuns of wine that could be carried in the holds). She arrived straight from the shipyard on 12 August 1840, captained by B Lyne. Was withdrawn in 1847 and then saw service in Gambia, West Africa.

Princess Alice, an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall, engined by Maudsley, Sons & Field and 110.1 burthens. She belonged to Dover ship owners, John and William Hayward of Snargate Street and came on station as a packet on 27 December 1843. She was purchased by the Admiralty on 27 January 1844 for £11,350 as a replacement for Beaver and was captained initially by Luke Smithett and from 1848 by Captain Edward Charles Rutter (1794-1880). She ceased to be a packet ship in February 1855 but occasionally returned to Dover in that capacity.

Onyx an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and tonnage 294 gross. A replacement for Arial she arrived on 30 January 1846 and made the fastest crossings between Dover and Calais from 1846 to 1848, taking, on average, one hour and twenty-five minutes.

Violet an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and tonnage 295 gross. She came to straight to Dover arriving 8 April 1846 as a replacement for the Swallow and captained by Lieut. Jones RN.

Garland a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and tonnage 295 gross. Built for the Dover packet service she arrived 27 May 1846 and captained by Lieut. Wylde RN. She made the quickest passage from Boulogne taking 1hour 50 minutes and regularly made the crossing to Ostend in 4hours 30minutes.

The Ondine an iron paddle steamer built and engined in 1845 by Miller, Ravenhill & Co of Blackwall, 86 burthens for Dover ship owners, Messrs Bushell. The Ondine, worked the Dover-Boulogne passage with the licence to carry the Indian mail. When the packet service ceased out of Dover, she was sold to Edward Baldwin (died 1848) the proprietor of the London Morning Herald. On 2 April 1845, Ondine made the crossing between Dover and Boulogne in 1hour 51minutes and was to break this record several times thereafter. Impressed, the Admiralty made Baldwin an offer for her and finally, in February 1847, £10,936 was accepted. Renamed Undine, she was commissioned for the Portsmouth – Le Havre crossing but occasionally coming to Dover on a temporary basis. In June 1848, she moved to Dover permanently as the relief vessel, with John Warman as her captain, until 1850 when she returned to Portsmouth.

The Vivid a wooden paddle steamer designed by Oliver Lang, Chatham Royal Dockyard, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and 352 ¾ burthen. She arrived in Dover from her maiden trials in 8 April 1848 and was captained by Luke Smithett (1800-1871) – the Commodore of the Admiralty Fleet.

Prince Albert arriving at Dover in the Ariel on 6 February 1840 for his marriage to Queen Victoria four days later. Dover Museum

Luke Smithett had been a captain in the Irish Packet service before coming Dover. Highly thought of, Smithett was usually selected to pilot or accompany the Royal yacht, and to conduct Royal visitors to and from the country. On 6 February 1840, he brought Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861) in the Ariel, to be married four days later to Queen Victoria (1837-1901). When the Princess Alice came on station, Captain Smithett took command and was not only proud of her, but also believed that she could not be beaten on speed. Following the arrival of the Onyx a race was arranged between the two ships. In a run of an hour and a half along the Kentish coast, the Onyx proved swifter by nine minutes. Captain Smithett on the Vivid brought Napoleon III (1852-1873) and Empress Eugénie (1826-1920) to England on 16 April 1855 to start a 6-day State visit. In Dover, the Royal couple were met by Prince Albert, Dover’s Mayor William Payn and other civic dignitaries and the Emperor conferred the French Legion of Honour on Captain Smithett. In 1862, Queen Victoria knighted him.

Back on 6 February 1844, with the opening of the South Eastern Railway (SER) the uncomfortable and tiresome mail-coach journey from London to Dover gave way to the considerably quicker train. In 1846 the Belgium Government started its own steam ship service between Ostend and Dover. Their first ship was an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare of Blackwall and named the Chermin-de-Fer. Her tonnage was 340gross and had two 60horse-powered circular cylinder direct-acting engines by Maudsley, Son and Field. The Chermin-de-Fer’s first official crossing was on 3 March 1846 and around 1851 she was renamed Diamant in order to conform to a policy of naming all Belgium’s early packets after precious stones. Their second ship was the Ville D’Ostende, 352 gross tonnage with her maiden voyage on 6 August 1847. She was later renamed Rubis and was built by John Cockerill, who had a shipyard at the French speaking Walloon city of Seraing, close to Liege, on the banks of the River Meuse, Southern Belgium. The 352ton Ville de Bruges later renamed Topaz followed the Ville D’Ostende. However, the service was not initially a financial successful. In 1847, the annual losses amounted to 300,000 francs and there was a call for it to be abandoned. The Belgium government approached Admiralty with a view to sharing the expenses and the mail service between the two countries and agreements were signed to this effect in October and November 1848.

The next Admiralty contract for French mail ran from January 1848 for one year and one month with the remit demanding acceleration in postal communication. On 2 September 1848, the Northern Railway of France opened their line to Calais and the question of restoring Calais as primary French Channel port came under discussion. At the end of January 1849, the Admiralty ceased running mail packets to Boulogne with Calais expected to become the principal port in France for British travellers. From the packet records of 1849, 1850 and 1851, it appears that there were two packet crossings a day from Dover to and from the ports of Boulogne, Calais and Ostend. Typically, the statistics up to the closing of the Boulogne packet route are espoused by those of the week ending 24 June 1848. That week, 900 Continental passengers passed through the English port with 500 going to Ostend, 300 to Boulogne but only 100 to Calais.

South Eastern Railway Company (SER) had opened their railway line to Dover on Tuesday 6 February 1844. Two years before Joseph Baxendale (1785-1872), the Chairman of SER had purchased the silted up Folkestone Harbour for £18,000. He immediately sold the harbour to SER, who then spent some £250,000 on deepening, constructing landing stages, passenger facilities, a viaduct across the town of Folkestone and a railway station. Folkestone Harbour opened on 24 June 1843 and SER hired ships from the Steam Navigation Company to provide a crossing to Boulogne until their own vessels were ready. From that time, they had regularly applied for the Channel mail packet contract but had been consistently refused.

Although the Admiralty adhered to the contract made with Boulogne, following the opening of the Calais-Paris railway connection that port was favoured. On 31 January 1849, the Admiralty ceased running mail packet’s to Boulogne and thereafter, Calais resumed its old position as the principal French port for English packets. SER, with one eye on the potentially lucrative mail contract and with the opening of the Calais-Paris railway line, introduced the Dover-Calais route to their schedules.

SER transferred the Princess Maud, the Queen of the French paddle steamers to Dover and persuaded the Admiralty to increase passenger fares on the Dover packets to equal the fares that the SER charged their passengers. Their argument was that the Admiralty were subsidising cross Channel passengers travelling on their ships. A new fare structure was introduced and the number of passengers using the packet boats fell. This led to yet another Inquiry where it was shown, by SER, that of the two packet crossings to Calais, the day mail train left London at 10.30hrs. It arrived in Dover at 14.30hrs, where the mail was loaded onto the packet boat and taken to Calais. The train left Calais at 18.30hrs and arrived in Paris at 05.30 the next morning and a reciprocal journey operated in the opposite direction. This, it was stated, was convenient for the delivery of mail, which took place approximately two hours later, but left the two capitals too early for businesses purposes. The evening mail train left London at 20.30hrs and Paris at 20.00hrs, which was convenient for businesses but the arrival in London, argued SER, was at 10.30hrs and Paris 08.45hrs with mail delivered some two hours after. The time the trains left was convenient but by the time the mail arrived a considerable part of the days business had been done.

The following year a Parliamentary Committee considered putting the transit of mails between Dover and Calais out for tender. SER gave evidence and offered to carry the mails for £9,825 per annum but the Committee found that the Admiralty were carrying the mails for £6,244per annum, so no action was taken. Captain Boys had been the Superintendent Commander of Dover’s Admiralty’s fleet and in 1841 he was followed by Captain Henry Boteler. By this time, there were six packets and all were repainted and renamed but the personnel remained the same. They were the Arrow renamed Aerial under Captain Luke Smithett, Crusader renamed Charon under Captain Edward Rutter, Ferret renamed Swallow under captain R Sherlock, Salamander renamed Beaver under Lieutenant Madge and Firefly renamed Myrtle the reserve packet.

The Great Exhibition was held in London in 1851, and SER lay on express trains between Dover and London, arriving an hour before either the Princess Maud or the Queen of the French were due into the port. Although the number of passengers using the packets coming to Dover increased significantly, averaging some two hundred passengers each voyage, the larger SER ships were crowded. SER’s gamble paid dividends! It was that year the first part of the Admiralty Pier was completed and on 19 June 1851 the Princess Alice, became the first cross-Channel packet to use the Pier on a regular basis. On that day, she landed 86 passengers and their baggage, after which the Pier was well used, except in rough weather.

Although the Onyx was scheduled, on 14 June 1851, to be the first packet to tie up on the partially built Admiralty Pier but as the harbour official log states, ‘This morning the Onyx had orders to land at the new Pier, but was unable to do so, being a strong SW wind, and the Pier works not yet affording sufficient shelter from the sea either at the buoy or the landing place, so as to lie at either with safety; also being low water spring tide at the time of arrival, there was not sufficient water to come to the buoy or the Pier without risk.’ The following day the Violet, coming from Ostend, made fast on a harbour buoy and sent the mails by boat to the Pier. She then proceeded into the harbour to land passengers.

Later, on 14 June, the steamer Father Thames, managed to make it to the Admiralty Pier and landed 50 passengers but two days later, 16 June, when the Vivid tried to get alongside, she failed due to a heavy swell. Instead she anchored in the bay with the mail and passengers taken off by Dover boatmen. Elsewhere, it states that the Onyx was the first ship to land passengers on the Admiralty Pier and that was on 15 January 1851. In fact, the Pier was not sufficiently advanced to take vessels and passengers at that time. Further, on that date, there was a gale blowing and the mail packets, including the Onyx, had to run for shelter in the Downs.

In 1852, the Violet was forced to put into Woolwich, on the Thames, following damage to her bowsprit and bow. Captain Baldock, inspector of the Dover Mail Packets, checked her out and following repairs she returned to Dover. At the time, SER, supported by the Times newspaper, were putting pressure on parliamentary representatives. Thus, the relatively minor accident and the cost of repair of the Violet was blown out of proportion. The Times reported that the Dover packet industry, in private hands would bring an annual saving to the government of £10,000. Eventually, in 1854, tenders were invited and SER made a bid but it was Jenkins & Churchward‘s offer of £15,500 that was accepted! Joseph Churchward, who ran the company, purchased a ship named Ondine as his first and only ship in his packet fleet! He then purchased the Undine and renamed her Dover and the Onyx and Violet and leased the Vivid and Princess Alice.

Packet Service II under Churchward Part I (1854-1857) continues

- First Presented:

- 02 March 2015