The Roman Painted House is one of the finest of its type in Britain and a major tourist attraction. The story starts over 2000 years ago when the Romans came to the shores of Britain. It then moves to more modern times and the long struggle by local amateurs to convince the established professionals to have a rethink. The story then looks at the discovery of Dover’s glittering prizes that were found when the professionals moved in and why most of these unique treasures were then reburied. The worldwide triumphs are covered and the dark days that followed. The latter helped to lead to the introduction of new legislation and are told from the perspective of this author. Finally, the events since that time and the recent national accolades that make the Roman Painted House a very special attraction.

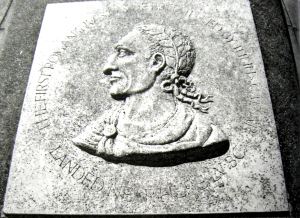

Long before Julius Caesar (100BC-44BC) commanded the first conquering expedition to Britain, the country had close trading ties with Continental Europe. Skilful warriors went from Britain to assist in repelling the advances of the Romans on the Continent. Julius Caesar’s attempted invasion was on 25 August 55BC of which he wrote in Commentaries on his Campaigns (using the third person) that ‘Caesar determined to proceed into Britain because he was told that in almost all the Gallic wars succour had been supplied from thence to our enemies.’ In a fleet of 80 ships and two galleys he ‘reached Britain with the first squadron of ships about the fourth hour of the day, and there saw the forces of the Britons drawn up in arms on all the hills. The nature of the place is this: The sea was confined by mountains so close to it that a dart could be thrown from the summit to the shore …’ Calling the place Dubris – meaning waters, it is generally assumed that he was describing Dover.

Julius Caesar went on to give an account of how the British forces were marshalled on the Eastern and Western Heights overlooking Dubris and this persuaded the fleet to take the next flood tide east and to make landfall at Walmer, East Kent. There the Britons, having followed the invasion fleet in chariots or on horseback, attacked but the Roman’s were victorious and made camp on the beach. Following the encounter, Caesar’s view of the Britons changed, for he wrote, ‘…by far the most civilised are those who inhabit Cantium, the whole of which is a maritime region; and their manners differ little from those of the Gauls’. Cantium means a rim or border from which is derived the modern name of Kent. It was nearly 100 years before the Romans returned during which time the Britons enjoyed relative peace with Continental contacts through trade and diplomacy.

In the summer of AD43, the Roman Emperor Claudius (AD41-AD54) ordered his army to make a second attempt to invade Britain. His force, under Aulus Plautius, consisted of approximately 40,000 troops landed at Richborough, near present day Sandwich, East Kent. The principal force in the army was the Roman Legion, a unit of about 6,000 men, supplemented by a large number of auxiliary cohorts. The cohorts were units of about 600 men drawn from the vast Roman Empire. Of the many cohorts serving in Britain the Cohors I Bataesiorum, appear to have been stationed in the South East of England. They stamped their tiles and other artefacts used in their buildings, CIB and many of these tiles have been found in the South East. At Richborough, the Romans established a bridgehead and commemorated their success by building a triumphal arch whose cross-shaped foundations still survive.

At first, the progress of the Romans was rapid but after the initial military success came a period of consolidation when much of southern England and Wales was under firm control. By AD100, most of the indigenous population had settled into a peaceful co-existence when farming, towns and various industries flourished. Roads, bridges, public buildings, aqueducts, schools, temples, churches, villas, palaces and factories were built. However, following the death of her husband the king of the British Iceni tribe of north East Anglia, Boudicca became the prime ruler. Shortly after, the Romans annexed Boudicca’s kingdom, flogged her and raped her daughters. Together with the Trinovantes of south East Anglia, whose capital was Camulodunum – modern day Colchester, Boudicca led a famous revolt and was killed in AD61.

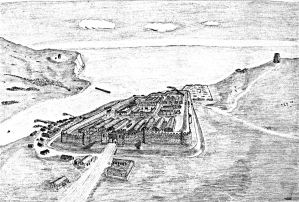

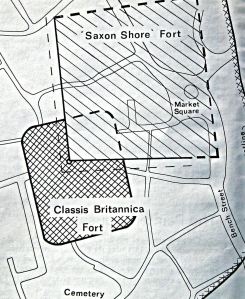

The power of the Romans was not affected by the uprising and they built a series of fortified ports with large garrisons for their provincial naval fleet around the coast. The fleet was raised by Claudius for the invasion of Britain and these forts were located in many places along the southeast and southern coast and on the Continental side of the Channel. Called Classis Britannica, the archaeological evidence of these forts is the inscription CLBR or variants on their artefacts such as tiles and building materials. The role of the Roman naval fleet was to ferry troops and supplies along the coast and rivers and to keep open communication routes across the English Channel. For a long time it was believed that the main bases of the Classis Britannia were Boulogne, in northern France, and Richborough in England. It was said that no such fort existed in Dover.

From about AD 270 Roman Britain came under attack from Saxon pirates and it became necessary to fortify the shores. The Classis Britannica forts were strengthened, replaced or new large strong Roman Shore (Rutupine Shore) forts were built. These forts were along the coasts of Kent, Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk and the Continental coastline on the opposite side of the Channel. Under the command of a Limen-Arch or Comes Littoris Saxonici the forts linked the military units. Comes Littoris Saxonici translates as Count of the Saxon Shore and often the forts are referred to as Saxon Shore forts, which causes a great deal of confusion so throughout this text the term Roman Shore fort has been used. The remains of the Roman Shore fort at Rutupiae (Richborough) are still visible and according to a late Roman military list, there was at Dover ‘The prefect of Tungrecanorum.’

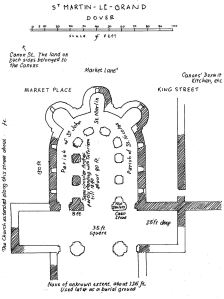

Sometime before AD450, control effectively ended from Rome and the civil administration and the economy in Britain totally collapsed. The Angles and Saxons (usually referred to as Saxons) invaded and over the next 200 years, seven kingdoms evolved. Dubris became Dorfa then Dofris and in the 7th century Widred, the Saxon King of Kent (c690-725), built a monastery with a chapel. Dedicated to St Martin, it was situated on the west side of what is now Market Square. Following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William I’s (1066-1087) army marched along the coast razing villages and towns to the ground and this included Dover and the monastery and chapel of St Martin. William I, a religious man, was so angry that he ordered the monastery be rebuilt with a great church and that it was to be dedicated to St Martin. It was said that St Martin-le-Grand was the most magnificent church in England. In the Domesday Book of 1086, the town’s name is given as Dovere.

By 1618 very little evidence of the Roman occupation survived in Dover beyond two structures, one on the Eastern and the remains of another on the Western Heights. Saxon buildings had, by that time, been demolished or incorporated into later buildings. That year, the council voted to use stones of the derelict Church of St Martin-le-Grand to be used to build Buggin’s Bridge over the River Dour to the seafront. Much of the east end of the Church was demolished in 1818 then later in 1826, the King Street – Bench Street road-widening scheme revealed what was believed to be part of one of St Martin’s under-crofts or crypts. In 1845, the archaeologist, Rev F C Plumptre described what remained of the ancient monastery and nearly twenty years later William Batcheller wrote that some of the mossy ruins still ‘overtop adjoining premises, and in the Market Square may still be seen the fragment of the north transept wall.’

It was conjectured, during the restoration of St Mary’s Church, that traces of structures were a Roman bath house. Alan Sencicle 2009

Rev Plumptre was asked to comment on findings during the restoration of St Mary’s Church in Cannon Street in 1843-1844 and identified traces of a Roman bathhouse. Nearby, in 1778-9, what were believed to be Roman walls were previously found. In 1856, some 20-feet (6 metres) down on land in St James’s Street, evidence of a Roman construction was unearthed. This comprised of four longitudinal wooden beams about 20-feet in length and each a foot square joined together to make a frame. Under the supervision of Town Clerk Edward Knocker (1804-1884) workmen dug a trench that revealed substantial wooden staging about 100 feet in length. Not only was it strongly built, there were few bolts or pegs holding it together and the discovery excited both local and national interest. It was concluded that the structure had been laid down ‘by the Romans as a hard or roadway to and from their landing place on what was a boggy shore and it must have been constructed at least 1,500 years ago.‘ In 1924 East Kent Road Car Company had a bus garage built in nearby St James Lane and when excavating the foundation pits a number of Roman artefacts were found.

Prior to the Knocker excavations, the structure on the Eastern Heights in the Castle grounds was believed to have been built by the Roman General, Aulus Plautius, as part of a building programme erected as aids to quell the rebellious Britons circa AD50. Following the excavation of the conjectured Roman quay, it was believed that the structure was a Pharos – a Roman lighthouse. At the time, the Pharos was classed as the tallest surviving Roman building in Britain.

Following the Restoration (1660), the installation of the Lord Warden took place on the Western Heights nearby the second known Roman structure, at the time called the Breden Stone – later Bredenstone. The structure was said to have mythological origins and was still visible in the 18th century. It was almost totally destroyed when the Western Heights defences were constructed at the beginning of the 19th century. In May 1861, Clement Tait, an engineer, working on new constructions in the Drop Redoubt on the Western Heights, excavated and recorded the Bredenstone when it was identified as the western Pharos and sister of the still standing Pharos within the Castle grounds! Together with the evidence of the Roman harbour and the two lighthouses or Pharos, it was conjectured that Dover was a port of significance during the Roman occupation.

In the winter of 1859-60, during excavations for the foundations of houses on Market Lane, several chalk coffins were found and a large number of low denominations Roman coins. Shortly afterwards, during excavations for Buckland School, London Road, a large quantities of Roman pottery was found, indicating to the archaeologists of the time, that there was possibly a pottery manufacture there during the time of the Roman occupation. In 1861, the Town Hall that occupied the centre of what is now the Market Square was demolished and about 10-feet down on a northwestern angle a tessellated pavement was unearthed. It was conjectured that this was possibly the site of a Roman luxurious bath.

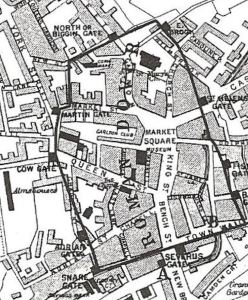

Rev Puckle’s map of what he believed to be Roman Dover surrounded by a wall with gates which he named from ancient documents. 1893

By this time most locals believed, from the evidence found, that Dover was occupied by the Romans and that they had built a significant harbour. Reverend Puckle, the Rector of St Mary’s church, published a map in 1893 showing what he believed to be the Roman town walls. However, Reverend S.P.H Statham, Rector of St Mary-in-Castro at the Castle, in his seminal work, The History of the Castle, Town and Port of Dover, (published 1899), supported the prevailing accepted view, writing that during Roman times, ‘a main road existed between Dover and London, which conclusively proves that a considerable traffic existed, and another road joined the town to Rutupiae (Richborough) … the port of disembarkation from the Continent.’ He went on to say that ‘during the days of Roman occupation Dover never had defending walls.’

‘Rubbish’ found while excavating for Lloyds Bank on the north side of Market Square in 1908. Identified by Eugene Amos – who took the photograph – of archaeological significance. Dover Museum

Mary Horsley (circa 1847-1920), in her booklet Old Dover and its Churches, recorded that in 1908, when Lloyds Bank was being built on the north side of Market Square, a large quantity of Roman tiling, Roman pottery of various kinds, Samian ware, Roman glass, etc. were found together with a lava millstone. As it was impossible to piece any of the fragments together, they were deposited in boxes in the Museum as ‘archaeological rubbish’. However, in 1913, at a depth of 9-feet, under the south east corner of the Market Square/King Street, where excavations were taking place for the then new London County and Westminster Bank. A larger number of red tiles about 1½inches thick and 8½inches square were found. One had the letters CIB and the others CLBR stamped on them. Photographer Eugene Amos (1872-1942), was the Honorary Archaeologist to Dover Corporation and identified these as Roman in origin and went so far as to say that they indicated the presence of a Roman Classis Britannica fort in the area. This was rejected by the eminent archaeologists of the time, who said that like the fragments on the opposite side of the Square, which Mary Horsley described, had been dumped and reminded Amos that he was a mere amateur. That year, 1913, Amos also identified remains found during the excavations for the foundations of the former head Post Office in Biggin Street as Roman.

In 1920, during excavations in nearby Cannon Street, more Roman tiles were found and it was conjectured that in Roman times the estuary of Dover’s River Dour, was much wider, tidal and navigable as far as Charlton Green one-mile inland. At first the harbour was in the centre of the estuary but sometime during the Roman period silting of the estuary had narrowed the Dour and the harbour was moved to the west. Then, for reasons unclear, the river separated into the East and West Brook finding its main outlet to the sea on the eastern side of Dover Bay, where, in late Saxon times, the harbour was built. These conjectures and the previous findings, particularly, those of Amos, were examined by Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1890-1976). In 1929, against received archaeological opinion, he stated that it was his belief was that the Romans had built a Classis Britannica fort on the Dour estuary, on the western side of Dover.

World War II east end of Snargate Street that revealed what was believed to be Roman remains. Kent Messenger.

Dover was heavily bombed and shelled during World War II (1939-1945) and towards the end of the War, the Dover Excavation Committee was set up. Their prime objective was the examining of as much of the blitzed areas as possible before rebuilding started. This was in an attempt to discover more about the early history of the town. In the spring of 1946, the foundations of chalk built dwellings and a Roman Road were unearthed between Queen Street and Market Street. Four years later portions of a Roman building were uncovered on the west side of Market Square. This was followed by the finding of a Roman Quay at Stembrook and a well in Market Square. Excavations for Maritime House, the National Union of Seamen offices in Snargate Street, revealed portions of two substantial Roman buildings. They were of dressed chalk blocks lined with tufa with the larger one having flint foundations overlaid with tiles but covered with a thick layer of soot. The smaller one was on a bed of chalk covered by a layer of reddish hard material containing broken tiles.

All of these findings and previous findings together with the pre-War thesis of Sir Mortimer Wheeler led Dover Excavation Committee to launch an appeal. This was for funds to finance search for what was believed to be a Classis Britannica and a Roman Shore fort beneath the Queen Street area. In an effort to cement their argument, the Committee highlighted the fact that on a late Roman Shore forts military list there was at Dover ‘The prefect of Tungrecanorum.’ However, academic archaeologists told the council that if either fort had existed they would have been on Castle Hill. Beyond the eastern Pharos. They said the only remains found in Dover were those thought by amateurs to be Roman. The council declined to back the project and it eventually died through lack of funding. Nonetheless, identifiable Roman remains continued to be unearthed.

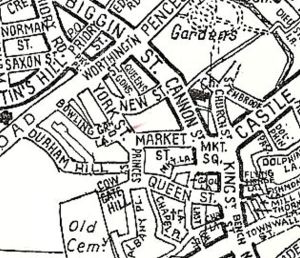

Map showing York Street, Princes Street & Queen Street area before the building of the York Street by-pass

Due to the increasing volume of road traffic to both Dover’s Eastern Dockyard and Admiralty Pier at the western docks through the town centre, by the mid 1960s plans were afoot for a dual carriageway by-pass.

This was to be along the line of the ancient narrow York Street and included a town centre redevelopment project. The envisaged York Street by-pass was to be in a deep cutting and the New Dover Group that had evolved out of the Dover Excavation Committee, persuaded the council to contact Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit (KARU) for their help. They had undertaken a number of important excavations ahead of proposed developments and KARU was made up of a full time team of professional archaeologists supported by an army of volunteers. Their objective was to: survey, excavate, record and publish details of sites threatened with destruction.

Although, within the archaeological world, the possibility of finding significant Roman remains in Dover was said to be negligible, in September 1970, Brian Philp a professional archaeologist with KARU, agreed to undertake a survey. Excavations were started in the Queen Street, Princes Street and York Street area, west of Market Square. This was along the line of the proposed by-pass and almost immediately, clear and considerable evidence was found in the shape of chalk block walls. These were identified as the Roman Shore fort built around AD270! By February 1971, copies of KARU’s interim report were sent to, amongst others, the Department of the Environment and Dover Corporation. By June that year, following a second excavation programme, more spectacular remains were found and the project was receiving worldwide interest. On 1 September 1971, the construction of the York Street by-pass began but there was no money available for preservation of the Roman remains or for re-routing the road. This was a known problem to the New Dover Group and other concerned locals as they had previously made considerable efforts to preserve historic buildings, some dating from Tudor times. Many had survived the destruction of World War II but had then been lost due to actions by developers.

The first job of the road builders was the laying of a gas pipe on the east side of the new road. Within a couple of days, the top of an hitherto unknown bastion relating to the Roman Shore fort was revealed and workers, armed with pneumatic drills, set about demolishing it. The archaeologists spoke to the sub-contractors and the trench for the gas pipe was moved inches away from the remains. However, on the morning of 8 September a mechanical excavator arrived, it had been brought in by the main contractor to move the trench back to the original course. The contractors showed no interest in the protestations of the archaeologists so they responded by painting a sign highlighting the needless destruction of the internationally important remains. Luckily, from 1960 to 1982, the independent television company, Southern Television, had a studio in Russell Street and that evening they covered the story but wrongly blamed Dover Corporation for moving the proposed trench. A meeting the next day not only righted this but led Dover’s Town Clerk, Ian Gill, to proclaim that ‘if the archaeologists say stop, then you (the contractors) stop – at least for 24hours.’

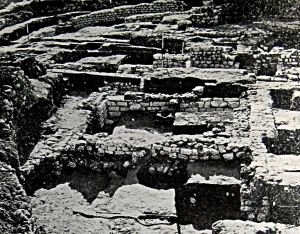

On 13 September 1971 a contractor’s bulldozer and mechanical excavator revealed another hitherto unexcavated area containing Roman masonry. This was in the area south of Queen Street and the archaeologists and their battalion of helpers moved in to unearth as much as possible in 24hours. In fact, they were given 72hours and the finds in the area included a barrack, drains, sewers and the south and east walls of what was, by this time, identified as Dover’s Classis Britannica naval fort dating from AD130! Further excavation showed that the fortress covered about two acres west of the present day Market Square and was substantially intact. The remains of some of the fort walls and several internal walls were 6-feet high – the most complete Roman military installation remaining in Southern Britain! Further, the site probably went a good way along the proposed York Street by-pass route and to areas beyond that could possibly have other Roman remains. Although Sir Mortimer Wheeler and Dr Arnold Taylor (1911–2002) – the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments – were informed, little could be done in the time allowed and on 18 September, the contractors moved in. Albeit, on payment from the archaeologists, the sub-contractors did remove tons of earth from selected areas that were remote from the road works.

In the meantime, John Clithero and Douglas Crellin, of the New Dover Group, held a meeting with Dover council while KARU contacted the Minister for Housing and Construction (1970-1972), Julian Amery (1919-1996). The Dover Express, in those days was based in Dover, and they headlined what was happening and Southern Television, along with the national daily Observer covered the story. Julian Amery ordered a three-week delay in road building while archaeological excavation and recording work took place. The situation demanded that the archaeologists and their helpers worked 24/7 and the use of torches and car headlights became important pieces of equipment! However, the weather was far from kind. Then, on 6 October, Julian Amery wrote saying that he had agreed to raise the York Street by-pass level by 12 to 18 inches in order to ensure the preservation of the walls of Dover’s Classis Britannica to the height of 3-feet. Adding that where the remains lie, on the east side, consideration could be given to their display, elsewhere they could be marked out on the surface where practicable. He finished his letter by saying that he had arranged for the road works to be delayed for a further month to allow time for recording.

South East Corner of the Classis Britannica under excavation. Brian Philp of the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit

This was a move in the right direction, but fell short of preserving Dover’s internationally renowned historic Roman remains. Therefore, KARU commissioned Chartered Surveyor, George Ashenden to look into the problem. Using Ministry of Transport specifications for trunk roads in urban areas, he suggested that the tail back of the Queen Street approach be raised and lengthened to enable the gradient of the proposed York Street to be increased. That York Street was to be a two carriageway road and he suggested that that road be raised with the two carriageways to be on split-levels. Dover’s Member of Parliament (1970-1987) Peter Rees (1926-2008) gave these recommendations along with the accompanying drawings to Julian Amery. Meanwhile, further excavations of the remains were being undertaken but with the deadline looming, the number of archaeologists and volunteers decreasing and the weather continuing to deteriorate a general air of pessimism prevailed.

On 16 November 1971, the contractors moved in ready to smash the largest excavated area the following day when Terry Sutton, a reporter with the Dover Express, arrived. He had an official government press release – Julian Amery, in consultation with his engineers, agreed to George Ashenden’s proposals! The northbound – western side of the by-pass – was to be raised by 5-feet 9-inches and the southbound – eastern side by 3-feet 9-inches – as we see today. Underneath is preserved a large part of Dover’s Classis Britannica and part of the Roman Shore Fort!

Stylised drawing showing the Classis Britannica, Pharos on the Eastern and Western Heights and Roman harbour. Dover Museum

Excavations continued on the Classis Britannica, uncovering 14 major buildings including a 15-foot high defensive wall – 10-feet thick built of chalk and tufa behind a 40-foot ditch ten feet deep. It was known that Roman forts evolved in rectangular pattern with rounded corners, two gates midway along the short sides linked by a main street, and two gates, main, and subsidiary, in each of the long sides. In the central area of the fort were administrative buildings, including the headquarters and a commanding officer’s house. On either side was accommodation for the troops, their mounts, and stores. In Dover, KARU found that Dover’s fort followed similar lines with barrack blocks, the granary, and infrastructure including roads, water systems, drains and sewers excavated. The buildings were mainly of chalk blocks, quarried locally, with clay roof tiles and timber frames and supports. An aqueduct, the remains of which were 2.10metres wide fed the water supply system and a 90cm high chalk block channel was found on the north side of Durham Hill in 1971. The line of the aqueduct from its source is not known, but the topography suggests that it followed the side of the Folkestone Road valley being fed from a natural spring about a mile from the fort.

Schematic Map c1974 of the location of the Classis Britannica and the Roman Shore fort – referred to as Saxon Shore fort. St Martin’s cemetery is shown at the bottom. Brian Philp of the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit

Besides incidental material such as prehistoric pottery, flint implements, Roman pottery, tiles etc., coins in mint condition of the period of Emperor Constantine (272-337 AD) have been found. Excavations show that three Roman roads began at Dover, one to Richborough, the second to Canterbury and the third to Lympne. Of interest, up until the building of the present A2 and A20, the main roads out of Dover followed similar routes. Another find was the base of a 25-foot catapult tower capable of hurling projectiles nearly a mile from the Roman fort. Further excavations uncovered many more Roman buildings showing that the army engineers selected a different site for the military Shore Fort to that of the Classis Britannica naval fort. The second fort being built closer to what was probably the harbour but over-lapping the northeast corner of the Classis Britannica. In 1979, one of the largest and most complete Roman military bathhouses in Southern Britain was discovered. 60feet by 120feet with at least 10 rooms within the 14-feet high walls, it was in a remarkable state of preservation and was temporarily open to the public. Like most of the archaeological remains found, to preserve it, those of the bathhouse were carefully reburied but before doing so, in 1984-5 eleven gemstones were found in a large drain carrying wastewater from the bathhouse. The depictions on the gemstones included Mars, panoply of arms, a browsing goat and the Goddess Tyche of Alexandria.

Mark Errington of Dover, in 1972, while helping to excavate a relatively small piece of land to the west of Market Square, discovered a large solid gold finger ring with a fine red garnet probably of the 5th-7th centuries. The ring was valued at about £10,000. KARU having discovered a considerable amount about the Dover Saxons, in August 1978 discovered the original Church of St Martin. The building was approximately 30feet by 65feet and made entirely of wood and the findings suggested that it dated from between the 7th and 9th century. In 1987, KARU found an 8th century Saxon hut cut into the ground, near York Street, within which were a number of pieces of Saxon pottery and loom weights. Excavations in the grounds of Dover College revealed remains of St Martin’s Priory, which had superseded St Martin-le-Grand, also clear evidence of pre-historic material. Another find was an ancient burial ground between Priory Road and Biggin Street, next to St Edmund’s Chapel. While other excavations showed that the River Dour valley was inhabited during the Bronze Age (2,100BC to 700BC).

Excavated ruins of the Roman Shore fort that included the 15-feet high wall found under the old market hall now Dover Museum. Brian Philp of the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit

In March 1972, Maybrook Properties submitted to Dover Corporation a ‘Piazza’ scheme to develop the west of Market Square, at an estimated cost of £5m. The scheme included shops, market, offices, a museum, pub and a multi-storey car park. All of which put the archaeological excavation programmes in jeopardy. To make way for the new development, the century old Market Hall was to be demolished and at the time Hatton’s departmental store, 45 – 47 Biggin Street and a family business founded in 1877, closed. With the threat of the Market closing, the number of market stallholders dwindled and the remaining 23 were moved to the vacated Hatton premises. Then the newly formed Dover District Council (DDC) kicked the stall holders out of Hattons in June 1975. Maybrook Properties built Maybrook House on York Street, damaging carefully buried archaeological remains but due to upheavals in the national economy, the Piazza scheme never became a reality. John and Mary Dixon, along with members of the New Dover Group, campaigned to save the Market Hall and in 1973 succeeded in having the façade Grade 2 Listed. However, due to the failure of the Piazza scheme, both the façade and the interior were abandoned and allowed to rot. The Hall was close to the location of the excavation sites and the archaeologists took the opportunity to undertake excavations within the old Market Hall. There they found more Roman remains including the 15-feet high Roman Shore fort wall mentioned above.

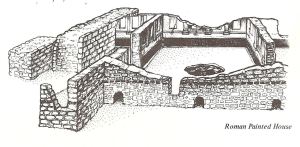

During the 1970 excavations a large but simple Saxon wooden hut built around AD800 was uncovered. When the rubble on which it stood was examined it was found to be the earthworks thrown up in connection with the construction of the Roman Shore Fort. At the time, a fine Roman building circa AD200 was glimpsed that had been preserved by the earthworks. Kept a closely guarded secret until July 1971, the building proved to be one of the largest and most complete Roman mansio or official hotels north of the Alps. As it was outside the Classis Britannica, it was probably built for high-ranking travellers maybe even Emperor Hadrian. The Roman Painted House, as it is now called, was excavated in 1971 and found to have been built of brick and flint, 60-feet by 120-feet and was at least two storeys comprising of at least six rooms. The walls in four rooms survive to a height of 4-6ft and the hard red floors covered a substantially complete and sophisticated under-floor heating system. The large arched flues, the various heating channels and the vertical wall-flues that kept the building comfortably warm can still be seen.

Within these rooms are over 400 square feet of painted plaster that include, above a lower red and green dado an architectural scheme of coloured panels 28 of which survive. The panels are framed by fluted columns that sit on painted projecting bases above a stage. Each panel contains a motif relating to Bacchus, the Roman God of wine. These panels give the House its modern name and are well worth seeing. Like the Classis Britannica, the House was built over an earlier building but some 70 years before the Roman Shore fort and was possibly partly demolished by the Roman Army during the construction of the latter fort.

The building was outside of the line of the then proposed York Street by-pass and expert opinion was unanimous that it should be preserved. DDC were not interested in Dover’s treasures so the Dover Roman Painted House Trust was formed and launched a £90,000 appeal in August 1975. This was to build a structure over the House to preserve the painted walls and the project was put out to tender. The builders’ costs were £20,000 more than the Trust expected so archaeologists involved in KARU, unpaid, undertook the management of the site and the supervision of sub-contractors. Carrying out most of the unskilled and labouring jobs on a voluntary basis after 180 days of non-stop work the building was constructed and the flat roof in position by mid-September 1976. Then began the task of consolidation and conservation of the Roman villa and its painted plaster walls. Of those active in raising funds, especially in London, was Dover’s MP, Peter Rees.

The Roman Painted House opened to the public on 12 May 1977, and within the first month over 20,000 people visited. It was recognised as the best-preserved building of its type north of the Alps and Dover was proud. DDC, who owned the site started to look favourably upon it and contributed £25,000 towards the permanent museum. A delegation of councillors went to the Department of Environment to ask for a another grant. In 1979, the House took second place in a competition run by the Illustrated London News to find the Museum of the Year, winning £500 donated by Imperial Tobacco. The Roman Painted House continued to gain accolades and awards and in July 1986, the Lord Warden, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, visited. The tour was scheduled to last three-quarter of an hour but the Queen Mother was so interested, she stayed one and a quarter hours! Trustees and members of staff were presented to the Royal visitor and the Director, archaeologist Brian Philp and Trustee George Ruck guided her throughout the visit.

Market Hall circa 1930s, Stall holders were moved out in the early 1970s and the building was to be demolished. In 1973 Grade II listing was achieved for the façade and it was agreed to locate the Roman Heritage Centre in a new build behind the façade. Dover Museum

Following the failure of the Piazza Scheme, in 1986 DDC appointed consultants Hillier Parker to advise on the potential of the land behind the shops on the west side of Market Square, next to the Roman Painted House. The consultants advised that the area should be used for a tourism-related project such as the construction of a Roman Heritage Centre to display many of the archaeological finds over the previous 20 years. Following Hillier Parker’s advice it was agreed that the project would be in-house and John Clayton, the Director of Planning and Technical Services, drew up a plan. The Roman Heritage Centre was to be on three floors and have a common entrance with the Roman Painted House, where a tourist information office was to be located. It was envisaged that this would encourage visitors to go to see other local historic sites. At about the same time the Kent Building Preservation Trust identified 15 properties in Dover that were endangered by decay. One of these buildings was the derelict Market Hall with a façade that was Grade 2 Listed. This tied in with the Clayton plan and the council gave permission to proceed with the three-storey Roman Heritage Centre there.

With the close collaboration of KARU, planning permission was given in 1988 and work started. At the time this author like many others was delighted but a change of policy by DDC to what became the White Cliffs Experience (WCE) now the Dover Discovery Centre and includes the library, changed many folks minds.

In essence, the WCE was to be Dover’s answer to the Heritage Centres then proliferating around the country and described by Martyn Harris of the Telegraph as ‘cosy and bowdlerised views of the past,’ (Daily Telegraph 24 March 1989 p15). The cartoon style displays ranged from Iron Age to present day with the focal point housed in a large central tower. This was the Time and Tide Theatre where Sydney the Seagull and Corporal Crab told stories of Dover assisted by a back projection of Dover’s white cliffs that talked and told listeners that it was a rock star named Cliff Face! The estimated cost, including off-site parking, was £22m and the beautiful Brook House along with the iconic Dover Stage were demolished to make way for coach and car parks. To help to pay for the WCE, it was envisaged that part of Pencester Gardens would be used to build a shopping complex in a lease and lease back deal.

A firm of consultants were brought in by DDC to spearhead the WCE project and their initial plan was to put the central tower over the Roman Painted House, driving four giant piles, spanning 21-feet across, through the internationally important building. KARU refused to cooperate and were quickly reminded that DDC owned the land. KARU suggested an alternative site where no known remains existed but DDC set up the Archaeology Advisory Board who would cooperate with their plans. The location was moved to the present position where giant concrete piles were driven through the buried Classis Britannica and other important archaeological remains!

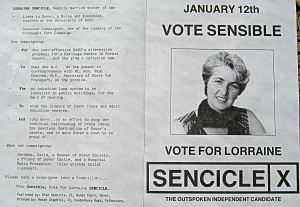

At the forefront of the protests were KARU archaeologists and when a two-seat by-election was called in Pineham (Whitfield) for January 12 1988, this author stood as an Independent candidate. At the top of my election manifesto was the alternative plan to the WCE. The archaeologists’ protests and my stance provoked a response that quickly became an horrific nightmare.

Reading my diary, the copious statements and letters of that time, the nightmare for me started on the day it became known I was running as a candidate. The telephone rang and when I answered a popular ballad was playing. This happened on a couple more occasions and then a man spoke – the same ballad was playing in the background. His voice was friendly though he did not give his name. Instead, he advised me to pull out of the election and put distance between the archaeologists and myself. He rang several times, always the same music was playing in the background but made assertions about the archaeologists. Namely, that one did not receive any remuneration so therefore was an amateur but had created a cult following. Further, the supposed ruins under the proposed WCE development were not what the archaeologists claimed them to be.

Then, on the morning of 23 December 1987, a reporter from the local independent radio station telephoned and asked me about allegations of corruption appertaining to DDC’s proposed WCE. He told me that he and other members of the media, had been informed of these allegations. Although names were not given, sufficient hints ensured that those who were accused could be determined. I was dazed and within seconds of putting the phone down another reporter rang. By the time the postman arrived, reporters from the local papers, radio and TV stations had telephoned asking the same questions. The postman brought a letter from DDC legal department, accusing me of ‘making unsubstantiated allegations regarding the award of the Heritage Centre (later WCE) contract to Bovis Construction Ltd and alleging corruption involving Council Members and others regarding publicity for the project.’ Later that morning I learnt that two of the archaeologists had received similar letters.

Bovis were from same corporate stable as P&O which was important to the people of Dover. In January 1987, European Ferries, operators of Townsend Thorenson, were taken over by P&O plc. Two months later, at 18.28hrs on the evening of 6 March, the 7,951 gross-tons former Townsend Thorensen ship, Herald of Free Enterprise, capsized off Zeebrugge on its way to Dover. There were 459 passengers and 80 crew on board, 193 lost their lives including 38 crewmembers, 26, of whom, were locals. P&O expressed regret but at the time they were cutting jobs, lengthening workers hours and cutting pay. Following the disaster, they carried on with this policy. In December 1987, the company told the National Union of Seamen that they intended to reduce the annual wage bill of £35 million by £6 million. This was to be done by cutting the number of staff by a further 20%, reducing earnings by an average of £25 a week, increasing the time worked on board their ferries by an extra month a year and obliging crew members to work very long hours. On 6 February 1988, the Seamen went on strike. The dispute was lengthy, bitter and the Seamen were forced to accept the new conditions. I had publicly reproached DDC for awarding Bovis the WCE building contract as, to my mind, it was not good for local public relations.

Following what should have been a joyful Christmas for us, the telephone calls started again but this time from an authoritarian sounding woman. Still the same ballad played in the background but if another member of my family answered the phone or I did not say anything, only the music played. Initially and when I was caught off guard, a woman spoke and I still shudder when I recall what she had to say. She reiterated all the same accusations as the man about the archaeologists, adding that it was they who were spreading untrue rumours of corruption. Yet it was me, she said, who would be sued which would lead to losing our home, my job etc. That I had two choices, testify that one (giving the name) was an amateur archaeologist who headed a cult following or kill myself. I saw a senior police officer and signed a form to have an intercept put on our phone for a trial period of ten days. However, after two days, the engineered telephoned to say that the police had heard the conversation and advised that we should go ex-directory immediately. We did.

The election went far better than I anticipated and although the phone calls stopped, they had affected me so much that I decided to quit local politics. Nonetheless, pressure to testify against the archaeologist was exerted in other ways. At the instigation of DDC, I was interviewed by two police officers from Kent Police Fraud Squad with my husband in attendance. I gave the Officers all the information I had on the Bovis contract and they appeared to agree with my comments. Regarding the proposed WCE project, I did say that it had been handed over to consultants and that in my opinion, the handling of sub contracts was not transparent such that the political faux pas of the Bovis contract, had been made.

I vehemently denied making the allegations of corruption and the police officers responded by saying that two councillors had made this accusation at a council meeting. This was held in private on the evening of 21 December, when they told councillors and council officers that they had visited my home that afternoon and I had made allegations of corruption against a local reporter. In fact, no such a meeting had taken place and I was able to prove it. Later it transpired that this accusation was part of a publicity stunt. The Fraud officers said that the horrific phone calls were a local police matter and not relevant to their investigation. Throughout the interview, the two officers kept returning to the archaeologist even saying that DDC had told them that he was not professional and was acting out of jealousy, supported by a cult following. Initially, I felt relieved after speaking about my concerns over the lack of transparency with the police officers but their obsession with the archaeologist niggled me. The more I thought about the interview, and in the light of subsequent events, I became convinced that the main aim of the officers was to elicit a corroborative statement over the allegations that had already been made to the police about the archaeologist.

Once the police had cleared DDC of corruption the aggression escalated. Everything I did, said, or did not say, was interpreted in a negative light. An attempt was made to have me compulsorily admitted into psychiatric unit but my husband, GP and the police all refused to sign the Mental Health Act 1983 Section committal form. I had complained to the Local Authority Ombudsman who spent a highly publicised day with DDC. Shortly after, I received his report in which he said that the letter I had been sent was a council oversight, and cleared them of maladministration. This, DDC interpreted in their PR as implying that the Ombudsman had investigated my complaint and cleared them of corruption!

To publicly emphasise the untrue accusation that the KARU archaeologist was an amateur, another group of archaeologists were brought in. They sanctioned the driving of the giant piles through the Classis Britannica – then the remains of the most complete Roman military installation in Southern Britain! Over this and the destruction of the other remains, the leading archaeologist of the group described KARU’s concerns as ‘simply ridiculous’ (Dover Express 6 January 1989 page 14). DDC, along with the archaeologist and the consultants spearheading the WCE project complained to the Institute of Field Archaeology in an attempt to get the target KARU archaeologist crossed off. At the same time a small annual grant to the Roman Painted House from DDC was stopped.

The White Cliffs Experience was officially opened by Princess Anne in 1991 but closed as an economic failure on 17 December 2000 – locally it was nicknamed the white elephant experience! In a letter written in 1988, from the architects of the WCE justifying the giant piles, it was said that ‘modern structures cannot be designed around archaeological remains.’ In 1990, National Planning Laws changed making it imperative for all applicants to consider archaeological aspects of the site when submitting plans for approval by councils.

Excavations during the building of the A20 were undertaken by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust in the late 1980s-early 1990s and the discoveries were many and important. The most significant was the Bronze Age Boat, that can be seen in a special gallery in Dover Museum. Near to where the Bronze Age Boat was found, at the junction of Bench Street and Townwall Street, a section of Dover’s medieval town wall and the massive squared timbers of a Roman harbour mole were found. About the same time, KARU unearthed what was possibly the house of the Commandant of the Classis Britannica in Albany Place. This comprised of two richly painted walls and the remains of an under floor heating system. In 1993, what is left of St Martin-le-Grand, by the steps leading to the Discovery Centre in the Market Square, received Schedule Ancient Monument Consent.

In 1994, local historian Joe Harman spotted ancient remains while keeping an eye on the digging of a new soakaway to the west side of St Mary’s Church. In 1778-9, what were believed to be Roman walls had been found nearby and in 1843-1844 traces of what was believed to be a Roman bathhouse were found. Harman notified KARU and subsequent excavations revealed part of an important Roman building, probably comprising of at least three rooms with under floor heating in the main room. A 5-foot high-mortared wall with many courses composed of Roman tiles, chalk blocks and flints were still standing. Fragments of the painted wall plaster can be seen at the Roman Painted House.

After five years of marginalization by DDC, in August 1995, following the election of Councillor Tony Sansum as the new Council Leader, the funding for the Roman Painted House was reinstated. Sansum had been a great support to me during the dark days and had repeatedly said that when he had the power he would make sure that the Roman Painted House would be put back on the list of council grants.

With the introduction of regular calls into the port of Dover by cruise liners, the Roman Painted House became the must see attraction by a completely new set of visitors. However, in November 2005, the Roman Painted House Trust announced that £40,000 a year was needed if the House was to survive as a museum. Then, on the evening of 15 July 2007, the Trust was faced with an additional worry. Following an evening out, two local women decided to take a taxi home and went to the taxi office in New Street, next door to the Roman Painted House. While waiting, one of the women decided that she needed to urinate, went into the Roman Painted House car park and climbed over the 3-foot white painted wall. The wall surrounds the House complex but having climbed the wall, the woman fell into the moat on the other side. She sustained a fractured skull that left her with permanent injuries. Using a no-win no-fee arrangement the woman sued the Trust and Dover District Council, who own the site, for £300,000 saying it was dangerous. In April 2014, at the High Court in London, Judge John Leighton Williams ruled that the woman was a trespasser in law and rejected her claim.

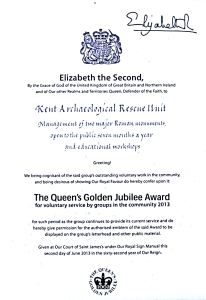

Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Award 2013 to the Roman Painted House. Brian Philp of the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit

The Roman Painted House is open to the public during the summer months. The entrance is on New Street and it is run by local volunteers. Even the professional archaeologists are unpaid. In 2013, the Roman Painted House was featured as one of the top 10 ‘hidden gems’ across England and Wales in ITV’s Britain’s Secret Homes and has won numerous national awards. For his work, Brian Philp received an Hon.D.Litt (Doctor of Letters) from the University of Kent at Canterbury (my university!). In 2013 he was awarded an M.B.E in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list.

Presented: 11 June 2015

Roman Painted House: http://www.the-cka.fastnet.co.uk has a link