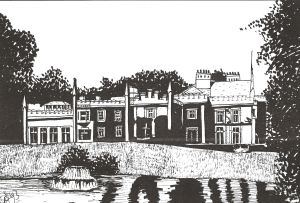

Pier House, Strond Street / Custom House Quay, the Fector family home and bank. Lynn Candace Sencicle 1993

When the Duke of Wellington’s (1769-1852) ship berthed at the Crosswall, Dover, following the Battle of Waterloo (1815), there was great rejoicing. Henry Jell, Emanuel Levey and Thomas Birch carried him shoulder high to the Ship Inn, on Custom House Quay. The Inn was next to Pier House, the family home of John Minet Fector and the night before, to celebrate the event, he had hosted a grand ball in the Assembly Rooms, on nearby Snargate Street. Fector, or John Minet as known to most, was born in 1754 and as a banker, ship owner, property owner and godfather of the East Kent smuggling trade, he was the wealthiest man in Dover. Further, he was good looking, charming, witty, clever and his benevolence seemed to know no bounds. These attributes, made him universally popular. (See Dynasty of Dover part IV Minet – Fector)

Brigade-Major George Ralph Payne Jarvis, born in 1774, was a recipient of John Minet’s hospitality when he had first come to Dover some nine years previously. It was the time of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) and George then held a much lower rank, so while the town was vibrant, it was also expensive. This was due to the inflationary pressures that war brought and the already thriving port was heaving with naval and military personnel. At the same time, there was a massive new military building project under way on Western Heights. George and Philadelphia, his wife, became acquainted with John Minet and his wife Anne socially and they quickly became friends. George was the youngest of twenty-one children of an Antiguan plantation owner and had joined the army at the age 17. In 1802 he married the wealthy Philadelphia Blackwell, daughter of a partner in Martin’s Bank, London. Their eldest son, George Knollis, was born the same year, since then they had added to their brood and Philadelphia was pregnant again.

John Minet rented one of his many large properties to George and Philadelphia in the then thriving maritime Pier District of Dover. Although Pier House actually fronted on to Strond Street with Customs House Quay at the rear. It was from there that John Minet ran the Fector bank and his shipping operations. Anne, his wife, preferred their mansion in St James Street, in the centre of Dover as there was plenty of room for their growing family of girls and it was near to her closest friends. Nearby, but nearer the sea than the Fector mansions, was the home of the beautiful, lively and clever Sarah Rice. Her teenage son Edward, born in 1790, was destined to join the second of Dover’s banks, Latham, Rice and Co. run by Sam Latham.

Sam Latham’s son Henshaw, born in 1782, was already involved in both the banking and shipping interests. Anne’s other friend’s home was on the landward side of St James Street, Sarah Gunman, who first arrived in Dover not long after George and Philadelphia. Sarah at that time, had recently married the much older James Gunman, who owned the vast estate, with an equally vast mansion, that went from the Maison Dieu to the Stembrook arm of the River Dour and fronted Biggin Street. (See Dynasty of Dover part III – Gunmans)

Within a few weeks, George left Dover to lead an expedition to Buenos Aires under Sir William Beresford (1768-1856) and John Minet and Anne promised to look after Philadelphia and the children. During the Napoleonic Wars, in order to draw the troops from the theatres of war and destabilize the French, the British sent numerous expeditionary forces to France or her allies territories. Spain, at the time, was an ally of France and as Buenos Aires was a Spanish possession it was decided to invade the City. Initially, the expedition was successful and on 27 June 1806, having put up very little defence, Buenos Aires capitulated. The Spanish then brought in reinforcements and eventually reclaimed Buenos Aires on 14 August with the British sustaining heavy casualties. The British surrendered but when George returned to Dover he had received the war medal with three clasps.

Over the next three years George, for the most part, was stationed in Dover and his friendship with John Fector deepened. Then on 30 July 1809 George, along with 39,000 other men, was sent to the island of Walcheren, at the mouth of the Scheldt estuary in the province of Zeeland, Netherlands. They landed on 30 July and it was, without doubt, Britain’s most disastrous expedition of the Napoleonic Wars. The objective of the British was to assist the Austrians, who were allies, to destroy the French fleet that at the time was believed to be in Flushing (Vlissingen). Before the force landed, the Austrians had already been defeated by the French who had moved their fleet to Antwerp. Nonetheless, the expeditionary force stayed until 9 December during which time 4,066 of the men died – only 106 in combat. The rest had succumbed to Walcheren Fever believed to be caused by a lethal combination of malaria, typhus, typhoid, and dysentery. By 1 February 1810, 11,513 officers and men were still sick and this included George. He returned to Dover but remained ill for some time after. Indeed, Arthur Wellesley who became the Duke of Wellington in 1814, requested that units which had served in the Walcheren Campaign should not be sent to him because the sickness had left them physically so weak.

View from the roof of the Fector Bank by George Jarvis. Western Heights on the left and Castle on the right

While George was ill, John Minet ensured that he received the best care possible. George, thinking he would never recover, resigned his commission. The military commanders thought differently and put him on half pay. While he was ill, George took up drawing and wood carving and eventually started to help out in Fector’s bank. John Minet’s brother, James, had been in charge of that side of the business but following James death in 1804, John Minet had looked after it. James young son Peter, born 1787, was learning the ropes but he, like John Minet, preferred the commercial/shipping side of the business. They were both grateful when George started to assume command especially as even the senior clerks were happy to work under George.

On 31 December 1814, when it was believed that the Napoleonic Wars were over, John decided to split the bank and commercial/shipping into two separate companies. The banking side was changed from Fector & Minet to J Minet Fector & Co under the management of George, while John, assisted by Peter, remained in control of the commercial/shipping side, which operated under the name of J Minet Fector. However, Napoleon escaped from Elba in early 1815 and George, who although was on half pay, played an active part in increasing defences locally – some of which can still be seen at St Margaret’s Bay. When Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and peace returned, George remained on half pay attaining the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in 1819. However, in 1816, George’s wife, Philadelphia, died, by which time she had given birth to seven children.

Following the victory of Waterloo, approximately a quarter of a million soldiers and sailors, many of them maimed, returned to Britain and were faced with unemployment. There was already inflationary pressures and poor crops leading to food shortages, exacerbated them. Income Tax, which had been introduced during the Wars, was abolished but it was replaced by taxes on staple commodities such as candles, paper and soap as well as luxury items such as sugar, beer and tobacco. To save money, town and cities cut the Poor Law relief rates that meant starvation was rife. This was not initially felt in Dover, as the wars had proved profitable and the town was able to bask in that prosperity.

Looking to the future, although John Minet had been the godfather of East Kent’s smuggling enterprises before and during the Wars, attitudes were changing. Like the other local smuggling barons, he recognised that it was expedient to distance himself from the trade especially when, in 1816, a Captain McCulloch proposed the establishment of the Coastal Blockade to deal with smuggling. The Admiralty frigates, Ganymede, Ramillies, and Severn, were put under his command and ships were watched, followed and frequently boarded if there was even a suspicion of contraband. If any was found, both men and vessel were seized and the owner was always assumed to be guilty. Initially the Blockade covered the Downs between the North and South Forelands, but was soon extended around the coast from Sheerness, on the north Kent coast, to Beachy Head, near Eastbourne, East Sussex. John Minet therefore decided that the future lay with using his ships for legitimate purposes only.

Parliament was dissolved on 10 June 1818 and at the time, Dover had two Members of Parliament. It was expected that one of the new MPs would be the sitting Member for Dover, John Jackson (1763–1820) and it was assumed that John Minet would be the other. Immediately George Page, Henry Morris, Edward Rutley and John Jell mounted a campaign on his behalf. Within days it was expected he would win by a landslide but John Minet was not at his town or his country house, Kearsney Manor, and was oblivious to all this activity.

When he heard he was in Boulogne and wrote a long letter. This was publicised and in it, he thanked his supporters but declined to stand. He did, however, suggest that his son – also called John Minet Fector (b 1812) – should represent the town when he grew up. As the election was fast approaching Edward Bootle Wilbraham (1771-1853) stood instead and was unopposed. Wilbraham was a veteran Parliamentarian who was happy to stand in Dover having married Mary Elizabeth Taylor daughter of Rev Edward Taylor of Bifrons, Patrixbourne.

At the Bank, George met the husband of Anne Fector’s friend, Sarah Gunman James Gunman and they immediately got on well. James invited George to his home, Gunman’s Mansion, to meet his wife, the former Sarah Hussey Delaval of Northumberland, born in 1772. Although younger than her husband, she appeared devoted to him. George had already met Sarah socially and knew of her philanthropic work, particularly in the education of local children for which she received well-deserved praise. Sarah, James Gunman told George, had financial problems that badly needed attending to and asked for his help. Both Sarah and her mother, also called Sarah, had inherited most of the shares in a palatial estate at Doddington, Lincolnshire and in 1816 Sarah’s mother had bought a further one-sixth for £12,000. This left just one share that was in the hands of an outsider, John Savile, 2nd Earl of Mexborough (1761-1830) but he was unwilling to sell.

Although Sarah’s mother was a frequent resident on the Lincolnshire estate, there were a number of financial transactions required of Sarah and her mother over which George’s expertise was needed. George agreed and carried out his duties well. When they were resolved, George remained a frequent visitor and a close friendship developed with George spending much of his spare time at the Gunman residence pursuing his passion both for drawing and for Sarah.

With George competently running the banking side and Peter running the shipping side of the business, John Minet took the opportunity to take Anne and his family around Europe on an extended tour. Local elections in Dover, in those days, were held in November and the Mayor was appointed a few days later. In November 1819, Thomas Mantell was appointed the Mayor for the fifth time since 1795, the sixth and final times was in 1824. Born at Chilham, near Canterbury, Mantell was one of Dover’s Surgeons but ceased to practise in 1793 when he was appointed agent at the port for prisoners of war. After the War he secured the post of agent for the mail packets a positioned he held for the remainder of his life. The Dover Post Office was on the quayside and the postmaster was sailmaker Peter Popkiss (1750-1822) it was from there that post was taken and also collected by the town’s inhabitants.

The mail to London was despatched at eight at night and arrived from London at six in the morning. Mail to Folkestone, Hythe and Romney, left the town at six in the morning and arrived from those places at half-past seven at night. Mantell, as the government agent, ensured that official mail to and from abroad was efficiently and speedily dealt with. The post for Calais was carried in Post Office Packet ships and crossed the Channel on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturdays, returning on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturdays. The Packets were sloops of about 700-tons and they were the Lord Duncan – Captain J Hamilton, the Chichester – Captain John Whitfield Rutter (1773-1825) and the King George – Captain M King. John Minet’s pride and joy was the King George and worked the passage along with a number of other ships belonging to the Fector fleet. The Latham, Rice and Co also had a large fleet and several other local ship owners worked the passage. The Fector and Lathams sailing ships and captains were:

Ant – T Barnett Catherine – A Fraser Countess of Elgin – R Hammond

Cumberland – J Hammond Dart – G Wilkinson Defence – J Adams

Dover- W Davidson Flora – A Watson Industry – Carlton

King George – Matthew King King George II – T Mercer Lady Castlereagh – W Mowell

Lady Jane James – J Hayward Lark – G Johnson Lord Duncan – J Hamilton

Poll – W Strains Prince Leopold – R Rogers Princess Augusta – J Blake

Princess Charlotte – E Hallands Queen Charlotte – J Thomas

Sybil – Thomas Middleton Trafalgar – Lieutenant T E Knight

Market Square with the Town or Court Hall in the centre 1822 by John Eastes Youden given by E E Pain. Dover Museum

Following the formal election of the Mayor, an eminent worthy was given an Honorary Freemanship of the town, if possible, followed by a feast that he paid for. Since the Honorary Freeman’s Act of 1885 these have been given for services to the town but in those days they were given to aristocrats or persons of prestige who resided in the town. On 7 November, following the election of Mayor Mantell, the Prince William 1st Duke of Clarence (1765-1837) later in 1830 crowned William IV, was given the Honorary Freedom of Dover.

He, along with his wife and a ‘foreign lady’, arrived at 16.00hrs at the Court Hall in the Market Square. There the whole of the Corporation plus the town’s clergy, principal persons of the town including both George, Peter and the Gunmans, senior military and naval personnel were assembled. The Town’s recorder, William Kenrick, asked the Royal personage if he was willing to take the oath and on affirmation the Town Clerk, John Shipman, proceeded to administer the customary oath. Led by Mayor Mantell, the throng repaired to the Ship Inn, Strond Street, where they all participated in a sumptuous meal and drank many toasts.

Two days later, on 9 November, it was apparent that forged Fector Bank £10 notes were in circulation. In 1816, the Gold Standard was statutorily established and the pound sterling was defined in a fixed quantity of gold. The following year the sovereign, containing 123.27 grains of gold, was put into circulation and under the gold standard system, paper money was convertible on demand into gold. This led to a massive increase in bank note forgery with, in 1817 the year after the gold standard was introduced, nearly 29,000 forged notes were presented to the Bank of England. Legitimate Fector notes equated with Bank of England notes, but it was the forged notes that were being exchange for sovereigns. To deal with this George issued both handbills and posters recommending that, ‘…till the offending parties are discovered, for the speedy discovery of whom no measures will be spared, all persons taking Ten Pound Notes will minute the back of them the day they are taken, and the name of the persons they are taken from.’ Eventually a Thomas Wildish was arrested, put on trial at the Old Bailey, found guilty and hung.

In the past, when times were hard, people in Dover turned to smuggling. Although the pre-war godfather’s of smuggling, such as John Minet, had given up the profession, it is well documented that Dover ships were bringing grain from the continent but how much was legal or smuggled is unclear. On 26 May 1820, the Coastal Blockade seized a smuggling galley and the crew of eleven men were committed to the town’s gaol, in Market Square, to await transportation. At 13.00hrs, as the prisoners were led out into the Square, there was a shout of ‘liberty‘ from the assembled throng and immediately the crowd rushed the prison wielding pick-axes, crowbars, saws and hammers. Mayor Mantell read the Riot Act but the mob managed to free the prisoners. The Coastal Blockade and the Preventative Water Guard, who served the rest of the country, amalgamated in 1821 under the Board of Customs, and renamed the Coast Guard and in recent times this was renamed Coastguard.

The Corporation’s surveyor, Richard Elsam, rebuilt the gaol on the same site from his own design. With what building materials were left, he built a row of tenements on Dieu Stone Lane. Elsam’s most famous building was on the seaside of Townwall Street (now part of Camden Crescent) for the Town Clerk, John Shipdem. It was an unusual turreted roundhouse with a Moorish theme and it was said that this was ‘so that the devil wouldn’t be able to catch the Town Clerk in a corner!’ Unlike the town gaol, which only survived thirteen years when it was condemned as unsatisfactory, the Round House survived until September 1940 when it was devastated by a bomb blast. After World War II (1939-1945) the equally iconic Dover Stage was built on the site but Dover District Council demolished this in 1989 and the site has since become a car park.

This was not the only time that Mayor Mantell read the Riot Act that year. On 29 January 1820 George III (1760-1820) died at the age of eighty-two. He had been deemed incapable of ruling the country since 1811, when his son, George IV (1820-1830), had reigned as Regent. The people of Dover saw the new King as extravagant, self-indulgent and ultimately to blame for their economic woes. They used the opportunity to express their feelings when his estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick, returned from the Continent. She arrived at the port on 5 June 1820 and was given a tumultuous welcome. However, when she arrived in London she was treated badly as witnesses were brought from the Continent to testify against her. It was on their arrival in Dover that rioting again broke out.

In London, Queen Caroline was stopped from going to the Coronation that was attended by Henshaw Latham. As a Burgess of Dover, he was participating in the Cinque Ports ancient tradition of burgesses carrying the Royal Canopy at Coronations. He later wrote that throughout the ceremony he could hear the piteous pleas of Queen Caroline asking to be let in. This was the last time the Cinque Ports exercised the right to carry the canopy over the Sovereign. Three weeks after the Coronation, Queen Caroline was dead and in Dover, the Corporation named Caroline Place after her. This was roughly where Stembrook car park is today. Following the ascendancy of George IV a general election was called with Edward Bootle Wilbraham and Joseph Butterworth (1770–1826) standing unopposed.

The Fector’s returned from the Grand Tour on 14 October 1820 and the town rejoiced. John Minet, with George and Peter at his side, organised an open day to which all the men in the town were invited and John Minet listened to their problems. These centred on the lack of work, the Coastal Blockade and George and Peter’s refusal to run the Fector smuggling enterprise. As East Kent’s ‘Godfather‘, they expected that John would soon have the smuggling industry running as smoothly as before but instead, John asked George to make all the financial arrangements for the building of a mansion on his Kearsney estate. John Minet’s father, Peter, had bought his Kearsney estate in 1790 for £70,000, which included Kearsney Manor, and on the meadowland where the Dour tributary from Alkham met the main stream from Watersend, near Temple Ewell, John planned to build the mansion that was to be called Kearsney Abbey.

The population for Dover in 1821 was, in total, 11,468 having increased by 1,221 since 1811. To help create employment in the town besides the building of Kearsney Abbey, John Minet organised the building of a replacement customs house, as the old one was derelict. He also loaned money to businesses to create employment and for these projects, it would appear John Minet liquidated much of his assets. On the home front John’s eldest daughter Anne Judith Laurie, known as Judith, wanted to marry French Canadian packet captain, Henry Pringle Bruyere. He was born in Dover in 1798 when his parents lived at Archliffe Fort. John Minet did not approve of the match and hoped that it would fizzle out. In the event that it did not, he made arrangements in the event the couple did marry, for a special trust fund of £10,000 to be set up on behalf of Judith. Out of this, Judith would receive an allowance and if she required any more money then it had to be approved by John Minet, or on his death, his son John Minet junior. If John Minet died before his son reached his maturity, then George Jarvis must approve it.

Harbour Entrance Dover by William Heath published 1836 by Rigden with steam ships. Harbour House LS 2010

In March 1819 the Elsie, a 37-ton steamboat crossed the Channel and on 20 June, the steamship Savannah, took 26 days to cross the Atlantic. The year before, on 14 June, the first steam packet, Rob Roy, had made her first crossing from Belfast to the Clyde. On Friday 15 June 1820 she was introduced to the Dover-Calais crossing and took 4½hrs to cross the Strait. The 88-ton ship was built by Denny of Dumbarton with 30 horsepower engines by Daniel Napier. The French government, attracted to the idea of steam, purchased the Rob Roy and she remained on the Dover-Calais run. The Post Office, impressed with steam packets, introduced the Monarch and Arrow in 1822 and in 1823 they acquired the swift 83-foot packet Spitfire with 40 horsepower engines.

This was of concern to John Minet as all his fleet were sailing ships and although steam packets did have drawbacks, they were faster. Following discussions with Peter and George, it was decided not to replace the sailing ships but to sell them when they were no longer serviceable. Besides the Post Office packet ships, the new paddle steamers working out of Dover in the 1820s and their owners were:

Britannia and Medusa – Bushells of Dover

Monarch, Salamander and Sovereign – Haywards of Dover

Dr George Dell, surgeon and the son of Captain Dell, of the Mail Packet Service was elected Mayor for the second time in November 1820 – previously in 1810. One of his ancestors, Edward Dell was a leading Non-conformist spending time in the Castle dungeon, along with Samuel Taverner, Richard Matson, Nathaniel Barry, Simon Yorke and Anthony Street, for his beliefs. George Jarvis negotiated with George Dell, on behalf of the Gunman family, about land on the west side of Biggin Street. The Doctor called his new acquisition Queen’s Gardens, probably after Queen Caroline, and planned to build a mansion but this did not materialise. Eventually the land was sold to build the cottages we see today.

The vergers of St Mary’s Church were also inspired and they organised a major refurbishment of the Church but according to Sir Stephen Glynne, ‘… many frightful windows inserted. A most unsightly effect is also produced by the addition of a new slate roof along the whole length of the north aisle.’ He was equally as scathing about the interior saying that it was over crowded with pews and galleries and finished by noting that, ‘the Corporation seat is behind the altar.’ Following the alterations George made a drawing of the interior.

Sarah Gunman was also caught up by the idea of construction for the betterment of Dover and to provide work. She particularly cared about the Dover Charity School in Queen Street that had originally been founded in 1789 for forty boys and twenty girls. The number of girls soon increased to thirty and since then, the demand for places had risen such that the school was badly overcrowded. Sarah set up a subscription and donations poured in. In 1820 the new Queen Street school opened with places for 200 boys and 200 girls for all the poor children in the town and neighbouring villages.

At East Cliff, where a mill had stood, four cottages were erected, number 3 was named after Blair Athol in Scotland by the resident, Mrs MacIntyre, and subsequently when more cottages were added it was named Athol Terrace. The harbour at the time was on the western side of Dover Bay and although the economic depression was lifting, across the Channel things were much brighter. The Channel shipping service was doing well from wealthy passengers and the export of goods and specie. Sometimes as much as £200,000 specie was carried on one crossing for speculation on the Continental money markets of Amsterdam, Hamburg and Paris. The passage was made in all sorts of weather and at all hours of the day and night. From London, mail coaches, heavily laden with gold would travel along the Kent turnpikes bringing their precious consignments.

Following the New Year of 1821 work on the harbour that had been carried out by engineer, James Moon, the harbour master was almost completed. This was to deal with the shingle bar caused by the Eastward drift that washed shingle into the Bay from the west and at neap tides prevented ships using the harbour. Before Moon started his work the Crosswall went from Union Street, then called Snargate over Sluice, to the Pier district and was built of wood. There was a wall across the Tidal harbour that created an inner harbour called the Bason into which gates were fitted opposite the mouth of the Tidal harbour. During neap tides, the gates would be opened in the hope that the accommodated water would wash away the shingle bar but this was not very effective.

The Bason, later Granville Dock. Entrance with Compass Tower on left and the Clock Tower on right. Dover Library

Moon reconstructed the Crosswall and new gates and sluices were fitted. When the sluices, on either side of the gates were opened they cleared the harbour mouth within an hour and according to Captain Post, ‘a French ship, of 240 tons register, drawing 12 feet, entered the harbour without difficulty, and at the lowest neap tides.’ However, the operating mechanism for the new sluices was cumbersome so it was decided to build an edifice to house them and to turn this into a feature. The final building was a clock tower, with four faces that, with great ceremony, was opened on 14 April 1830 and George Jarvis attended. Because of the lack of symmetry, a second tower was built and this had four compass faces. The clock tower is the same one we can now see on the seafront.

The cost of the harbour work was £81,500, whereas, the passing tolls – the tax on ships passing Dover harbour while traversing the Dover Strait – on average only amounted to £10,500 per year and dues collected on ships using the harbour (tonnage dues) only came to an average of £1,150 a year. On both of these a shipping tax of 6% was levied. During the preceding five years £23,500 had been borrowed to pay for the harbour works and together with the interest that had to be paid to the Fector and Latham banks on loans taken out in the 1790s, the total annual interest was £1,500 a year. To meet these debt repayments, in 1820 Sir Henry Oxenden, the Managing Commissioner of Dover Harbour Commission, loaned a further £4,500 and in June 1822, £1,500, then a month later an additional £2,500, all at 4% interest. To meet all the debt repayments the Harbour Commission appealed to Parliament who set up a Committee on Foreign Trade to look at works being carried out at both Ramsgate and Dover harbours. Their response was the opposite to what the Commissioners had hoped. The Committee said that due to the reduction in trade and the large sums paid by ships for the maintenance of the harbours, Dover Harbour Commissioners should consider reducing tonnage dues!

Ship builders on Dover beach 1820 by George Jarvis before the construction of the town mansions in 1818

Robert Jenkinson (1720-1828) – Lord Hawksbury (1796) and later the Earl of Liverpool (1808) – was appointed the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports on 30 January 1806 and by virtue of this office was also the Chairman of Dover Harbour Commissioners. The Register (now Chief Executive) was the financially astute John Shipdem and banker Sam Latham together with Thomas Bateman Lane, were the joint Treasurers. The shortage of money for harbour works was a long-term problem and in 1816, the Commission decided that instead of using the old revenues – the money earned from rents from buildings on the Commission’s lands – for harbour repairs, that they would use it instead for building purposes.

All reclaimed land, by the 1606 Dover Harbour Act, belonged to the Harbour Commission and Mr Horton, the Surveyor of Buckland, was called in. On 16 November 1816 he presented plans to build 96 large residences on a proposed street running parallel to but on the seaward side of Townwall Street. It was agreed that except for the initial cost which would come out of old revenues and borrowing, the project would be self-financing. That is, the next stage of the project would not commence until the Commissioners had accrued enough capital to pay off the original debt and had sufficient to start the next stage. The money for the first stage of the development was borrowed from the Fector and Latham banks and was started in 1818 with four blocks of town mansions with lawns in-between. The project was named Liverpool Street, after the Lord Warden.

Following the Napoleonic Wars the demand for flour had slumped, hitting Dover’s milling industry hard. In 1814, William Kingsford bought Buckland corn mill for £1,120 and the adjacent lands from Sir Thomas Hyde Page, the Military Engineer for £5,750. He rebuilt the corn mill we see today and it commenced grinding a year later. At the time it was a good buy as the town was feeding both the navy and army stationed thereabouts. However, when the Wars were over the demand for flour dropped. In 1821, John Minet bought the Town corn mill, which was dismantled, and the internal workings were used to pump water to Kearsney Abbey. In 1821, Kingsford borrowed £6,000 to expand the lower Buckland paper mill, next to his corn mill and built the cottages that can still be seen along the London Road, for his paper workers. The year before he had bought Charlton corn mill and the adjacent Charlton seed mill, grinding corn in the summer and rapeseed in the winter to produce oil seed cake for cattle. He borrowed £5,000 from the Fector bank to enlarge the buildings and improve the plant.

The Limekiln Street corn mill was in the possession of the Fector bank following the bankruptcy of Peter Becker. As the economy started to pick up, Joseph Walker, of Dover’s brewing family bought it and converted the mill for the purpose of producing oil seed cake. The mill grew into a complex that became known as the Oil Mills. To supply the steam, the mill had its own waterworks, at the time a wonder of modern technology. With the increase in the demand for flour, hoys (small cargo sailing ships) brought grain to be milled in Dover and then took the flour up to London. This gave another of Dover’s milling families, the Pilchers the impetus to rebuild the Town mill, using loans from the Fector bank. They also employed Edward Powell to run it and having taken over the Stembrook mill from the Navy they employed Julius Winter to run that.

The paper mills had also been hit by the economic downturn and in 1814 Buckland paper mill had suffered a disastrous fire. Four years later, when the economy started to improve, it was rebuilt but its owner, Thomas Horne, wanted to retire and put the mill up for auction in 1820. Out of the proceeds he built, in 1823, Buckland House, on Crabble Hill that still stands today. George Dickinson, brother of John Dickinson the famous paper manufacturer leased Buckland paper mill in 1822 having borrowed £30,000 from the Fector bank and built a steam driven paper mill at Charlton with a house next door. This he called Brook House, not to be confused with the iconic Brook House. Eventually, his house became part of the former Royal Victoria Hospital on the High Street. Dickinson also built the cottages on London Road for his paper workers and leased Bushy Ruff mills in 1826. William Phipps, the owner of River and Crabble paper mills died in 1819 leaving his business to his sons Christopher and John. In 1825, they patented the dandy roll, invented by John Marshall. This was a wooden roller covered with a wire cloth and used to add watermarks for making Indian currency paper.

Letter from Fector Bank signed by George Jarvis announcing the death of John Minet Fector dated 15 June 1821

John Minet Fector died suddenly on 12 June 1821 at Kearsney Manor and everything in the town stopped on the day of his funeral. The route between Kearsney Manor and St James’s Church, where a mausoleum was later constructed, was said to have been lined by every man, woman and child in the district. It had already been agreed that George would remain manager until John Minet’s son, John Minet junior, came of age. Unfortunately, it would appear that not all of the Fector family agreed as John Minet’s cousins, Isaac and John Lewis Minet came from London with the view of taking over the bank. George refused to comply and re-registered the bank as J Minet Fector & Co but had to move location to Snargate Street as the Minet brothers claimed Pier House. Isaac and John Lewis Minet, under the name of Minet Brothers & Co on 7 September 1821, opened their bank at Pier House on Strond Street. One of their partners was banker Lewis Stride who was known to be a very competent banker. The shipping side of the Fector business was taken over by Peter Fector.

- Presented: 08 August 2015