In Packet Service part II it was explained why the government, in 1853, decided to put the packet contracts between Dover and Calais and Dover and Ostend out to tender. At the time, the South East Railway Company (SER) had assumed that they would win the contract as they had the ships and resources but a syndicate headed by Joseph Churchward (1818-1900) undercut them. Churchward was a nautical journalist for the London Morning Herald with Machiavellian personality who lacked the finance and expertise to run a packet service. Further, he only had one small ship, the Ondine (II), an Iron paddle Steamer built and engined by Miller, Ravenhill & Co. in 1847 and 101.1 burthen.

On winning the contract Churchward bought three ex-Admiralty packet ships by instalments and underwritten by his close friend and ship builder Charles Mare. These were, the Onyx an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich – tonnage 294 gross and in 1854 renamed Vivid II. The Undine an iron paddle steamer built and engined in 1845 by Miller, Ravenhill & Co of Blackwall, and 86 burthen, renamed Dover and the Violet, an iron paddle steamer built by Ditchburn and Mare, Blackwall, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich with tonnage of 295 gross.

Shortly afterwards Churchward bought the Garland a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich with tonnage of 295 gross. She had previously worked the Dover packet service for the Admiralty and was renamed L‘Alliance in accordance with his French contract for carrying mails from France to England in 1855. That year Mare built two luxury paddle steamers for Churchward. They were the Empress and Queen and were 123.5 burthen with 2 x 50 horsepower engines made by Ravenhill, Salk & Co. These were primarily used to fulfil the French contract but he also had the contract to carry Belgium mails as well as his initial British Admiralty contract. To comply with the French contract, he employed French crew for daytime crossings and British at night. Further the Queen wasShortly afterwards Churchward bought the Garland a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich with tonnage of 295 gross. She had previously worked the Dover packet service for the Admiralty and was renamed L‘Alliance in accordance with his French contract for carrying mails from France to England in 1855. That year Mare built two luxury paddle steamers for Churchward. They were the Empress and Queen and were 123.5 burthen with 2 x 50 horsepower engines made by Ravenhill, Salk & also called La Reine when the French crew were on board and the Empress the Imperative.

Without offices or a base of any kind in Dover, Churchward managed to persuade the Admiralty to allow him, temporarily, to use their packet yard and offices on Snargate Street for £120 a year. These backed onto what later became Granville Dock where he set up workshops headed by Timothy Harrington as superintendent. Harrington was part of Churchward’s original syndicate and in consequence was very well paid, receiving a salary of £450 per year plus 10% of the profits made. Harrington slowly turned the site into a successful repair yard with skilled men, apprentices and workshops. Further, Churchward hired competent experienced officers and men to crew his ships including the highly respected former Commodore of the Admiralty packet service, Captain Luke Smithett who headed Churchward’s marine operations. In November 1854, Churchward put the company on a legal footing and named the Dover Royal Mail Packet Company. However, Mare, his financial backer was declared bankrupt in October 1855 and on the night of 5-6 January 1857, the Violet was lost with all hands. Further, the Violet was underinsured and it would cost £14,000 to replace her. Following the demise of Mare, Churchward’s financial guarantees were gone and with the loss of the Violet, Churchward was also in danger of being declared bankrupt.

In 1856, Churchward had bought the 149-ton gross iron paddle Thames pleasure steamer Jupiter, cheaply. She was not fitted out for the packet industry so had been used as a relief ship and even in early 1858, when he badly needed another ship, Churchward recognised that she could not be used. Cap in hand, Churchward turned to the Admiralty for help and took along Smithett. The Admiralty agreed to lease, gratuitously, the Princess Alice until 17 April 1857 and the Vivid (I). The Princess Alice was an iron paddle steamer 110.1 burthen and the Vivid (I), a wooden paddle steamer of 352 ¾ burthen that was a great favourite of Smithett. The Vivid (I) stayed on the Dover – Calais service until 14 May 1857 from then on the Jupiter undertook the packet service on a temporary basis.

Even though Vivid (I) had been leant to Churchward, the Admiralty still had first claim and in March 1857 a Mr Jeffries used her for an Admiralty experiment. Jeffries had patented a smoke consuming apparatus that, he claimed, would help in fuel economy and the Vivid (I) was sent to the Admiralty yard at Woolwich where she was fitted with Jeffries apparatus. She was then brought back to Dover and went into service that evening. The weather was fair when Captain Hammond took her on the Ostend night mails delivery. The two-way crossing took eight and three-quarter hours and the amount of fuel used was 75-80% of what would normally have been used given the conditions. Further, it was particularly noted that the dense black smoke the ship normally emitted was greatly reduced which pleased the passengers. Churchward asked to keep the fitment and suggested that it should be used but the recommendation appears to have come to nothing.

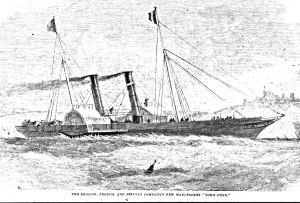

Mare’s father-in-law, Peter Rolt (1798-1882), reconstituted the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company and Churchward, who had two ships for his packet service on the order books one of which was about to be launched. Frederick William IV (1840-1861) of Prussia had been very generous to the widows and orphans of the crew of the Violet after she was lost in January 1857. In respect of this, Churchward decided to name his new ship Prince Frederick William of Prussia – usually shortened to Prince Frederick William. The 215-ton gross iron paddle steamer was designed by James Ash, 180-feet in length and 20-feet beam, 203-tons gross with 2x75horse-powered engines and a boiler pressure of 24lbs.

When he had placed the order, Churchward and Mare had decided that she would be the last word in comfort and speed but at the time Churchward only paid for materials and Mare the workmanship. With Rolt in charge, Churchward was expected to paid the full market price. The Prince Frederick William was the first ship to leave the newly formed Shipbuilding Company and this roused a great deal of media interest. Always the publicist Churchward organised a special trial that took place on 6 August 1857. Between Brunswick Wharf, Blackwall and Woolwich Dockyard on the Thames, the Prince Frederick William’s average speed was recorded as 17½knots and it was acknowledged that she was one of the fastest vessels in the world. On board, her fittings were the height of elegance and luxury and the national papers also emphasised this. Two days later, she was in Dover undertaking her maiden voyage with the mails to Ostend.

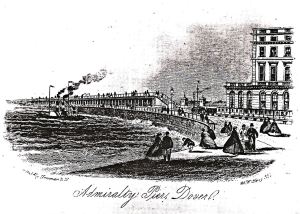

Churchward, did not have a clue how to pay for the Prince Frederick William so in the hope of providing much needed finance, Churchward applied and won the India and China mails contract with the Post Office. His major selling point was the Admiralty Pier that although not completed, ships could berth alongside. This meant that at Dover, Churchward was not handicapped with a tidal harbour that could only be used twice a day. However, the contract stipulated that the service was to be to Boulogne and that the Prince Frederick William was to be used. At the time, the Post Office Authorities were proud of the speed of their service from London to Folkestone from where SER, who had previously held the contract, took the mails to Boulogne. From Boulogne to Paris and then onto Marseilles, in the south France, the journey was fast and efficient. The only stumbling block to this fast service had been Folkestone Harbour, which was tidal. Churchward, to get round the Boulogne problem, decided to use the Prince Frederick William for his Admiralty scheduled, Dover – Calais service and hire six-oared boats to take the mail between Boulogne and the Prince Frederick William when she reached the Calais Roads in the Channel. Unfortunately, for Churchward the contract did not provide the finance he desperately needed as the sheer amount of mail meant that he frequently had to hire four and sometimes six rowing boats to make the Boulogne connection.

In January 1858, following continual arguments, Churchward gave his marine superintendent, Timothy Harrington, three months notice. In April, when Harrington had ceased to work for Churchward, he started legal action. Harrington stated that he had not been paid the 10% of the profits, as had been agreed. Churchward countered this by saying that no profits had been made. Nonetheless, Harrington continued to pursue the matter, widening his action until in 1860 a lawsuit partially upheld Harrington’s claims. These ongoing legal costs took their toll on Churchward’s already financially dire situation and he still had to pay for the Prince Frederick William and the other ship on the order books. In the end, he was forced to resort to selling his two older prize ships, the Queen and the Empress. Churchward offered the two ships to the French government who agreed a good price and the deal was sealed in March 1858.

With Harrington gone, Churchward was left with the responsibility of the ship repairs. The Prince Frederick William was accidentally beached at Kingsdown, east of Dover, on 3 February 1858, causing her hull to be stoved in. Later that year, the Vivid (I) ran down a fishing smack causing three men to drown and damage to the ship. The following year, on the night of 26-27 February 1859, the Prince Frederick William, with Captain James John Pittock (1827-1899) in command, collided with Calais Pier. A northwest gale was blowing, which made Calais harbour difficult to negotiate even though the light indicating access was lit. Six of the 37 passengers were taken ashore on the ship’s boat and the new Calais lifeboat came to the rescue. The men had just taken the eighth passenger on board when the boat was thrown so heavily against the Prince Frederick William that the lifeboat capsized and three passengers were drowned. The remaining 23 passengers stayed on board the ship and when the tide ebbed the following day, the crew, carrying the mails, walked ashore. Captain Pittock was suspended from duty and a four day enquiry was held at Dover. It was found that the accident was due, in the first place, to Calais light indicating that there was sufficient depth of water to make the entrance. Further, the sea conditions would have made the entrance into the harbour difficult normally but due to the lack of water, impossible. Captain Pittock was exonerated and returned to duty. However, within a month, when easterly gales were delaying the packet service, questions were being asked in the national press as to why a bit of wind was causing delays!

Churchward and Smithett, in April 1858, having publicly aired their views on forthcoming changes in passport regulations, were invited to meet a Mr Fitzgerald at the Foreign Office. In England, Henry V (1413-1422) by Act of Parliament of 1414 is credited with inventing the first true passport. Louis XIV (1661-1715) of France, granted personally signed documents that allowed the holder to ‘passe port,’ meaning ‘to pass through a port’ as most international travel was by sailing ships. From this came the term ‘passport’. From 1772, British passports were issued but written in French and from 1794 they were issued by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. British passports could be issued to a person of any nationality as a promise of ‘safe conduct’ from the British monarch and authorised the holder to travel wherever they wanted. However, these passports were only available to the aristocracy be they British or foreign nationals. The remainder of society, particularly merchants, bank managers and the middle classes in general, had to purchase passports from authorised diplomats and consulars representing the specific countries they were to pass through, which was cumbersome.

In France on the evening of 14 January 1858, Louis-Napoleon III (1808-1873) and his wife Eugénie escaped an assassination attempt unharmed. The ringleader of the conspirators was an Italian nationalist, Felice Orsini (1819-1858) aided by a French exile living in London, Simon Bernard. Orsini was captured, tried and executed but as Bernard held a British passport, the British government refused to extradite him. In response, the French refused to acknowledge anyone travelling on a British passport and it was this that had led to an amendment in the regulations.

From 3 February 1858, the British government ceased to be responsible for other nationals and stating that, ‘Every Continental Prince, by his own agents is to look after his own people.’ Passport application forms were issued to those who asked for them and they had to be filled in by one of the persons making the request. They then needed to be countersigned by an authorised person and sent with the remittance to the passport office, Downing Street, London. More than one person could share the same passport, such as a husband, wife, their children, tutors and their servants. The authorised persons were initially magistrates, justices of the peace or mayors of corporate towns, but this was soon after extended to include other designations.

In some ports, designated agents were appointed to issue passports instead of sending application forms directly to London and in Dover this was Samuel Metcalf Latham, whose offices were on Union Street. The fee was fixed at 6shillings of which 5shillings was the official stamp duty. The main complaint that Churchward and Smithett discussed with Mr Fitzgerald, concerned travellers who crossed the Channel, for social or business purposes and only stayed for a short while before returning to France or Belgium. It was agreed that in such circumstances, as long as the person held a return ticket, they could disembark at Dover undertake their requirements without an official passport. In June 1856, the French authorities agreed that passengers from England holding return tickets did not require passports for short-term stays. Further, the excursionist was not required to go through customs.

Churchward had used his journalistic skills on behalf of the local Conservatives in the General Election of 1857 but the two Whig candidates, Ralph Bernal Osborne (1808-1882) MP 1857–1859 and Sir William Russell, (1822-1892), were elected. The Whigs, under Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784-1865) held a significant majority of the seats and Osborne was appointed Secretary to the Admiralty. In this role, Osborne was instrumental in proposing the abolition of the Harbour Commissioners and his work ultimately led to the 1861 Harbours and Passing Tolls &c. Act that abolished the Commissioners and set up of the Dover Harbour Board. During this time, the Commissioners made sure that their house was in order, including looking at their properties to ensure that they were legally compliant.

The Admiralty packet yard had been sublet, on a temporary basis, to Churchward at £120 a year since 1854 and the many extensions had been built without permission. The Harbour Commissioners demanded that they be demolished and Churchward was evicted. He tried to rent alternative premises but was continually thwarted by the Commissioners as he would become a sub-tenant. The Admiralty suggested that he had his ships repaired at the Naval yard at Woolwich, paying the commercial rate and buy or rent property in Dover for his administration. Churchward could not even consider paying the full commercial rate for repairs even if he could, by taking his ships to the Thames would take them out of service for too long. At the lower (west) end of Snargate Street, the London Chatham and Dover Railway Company (LCDR) were excavating a tunnel for their line from what would become Dover Priory station to the harbour. Nearby was a vacant plot, which Churchward bought and built his own Packet Yard.

Throughout this time, Churchward kept up persistent lobbying for a seven-year extension of his Admiralty contract to bring it into line with his Belgium contract and what he hoped would be a renewed French contract. The Belgium contract expired in 26 April 1870. Within the Admiralty he had considerable influence but the Conservative Postmaster General, Admiral Charles Abbot, 2nd Baron Colchester (1798-1867), opposed the move. On 16 April 1859, Churchward received a communication stating categorically that the Admiralty contract would cease on 20 June 1863. This, he believed, was due to the influence of Bernal Osborn and responded by contacting his friends at the Admiralty office. At about the same time as Churchward received the letter from the Postmaster General, a general election was called and immediately he used his journalistic skills to try to influence the outcome. Churchward wanted to secure the election of two Conservative candidates whom, he believed, would support the extension of his contract. As nationally the Conservative Party was in disarray it was expected that the incumbent Whig, now the newly formed Liberal party, MP’s for Dover, Bernal Osborn and Sir William Russell, would win.

The hustings, in those days, were erected in Market Square where the partisans would verbally propose their candidates to the electorate. Locally the weaker Conservative Party fielded Sir Henry Leake and William Nichol. Both were in their 70s, highly thought of and approved by Churchward. Sir Henry was a Lord of the Admiralty while William Nichol was a Liverpool merchant and a Director of the London and County bank. By most accounts, the election process in Dover that year, was one of the dirtiest ever witnessed with threats of unjustifiable legal action, bribery, treating (paying for expensive lunches etc) and threatening prize fighters.

Churchward used the local newspapers, Dover Telegraph and Dover Chronicle, to support the Tory candidates and run the Liberal ones down and it was well recognised that it was Churchward’s influence that Leake and Nichol won by a large majority. The former incumbent and Churchward‘s nemesis, Bernal Osborn, came bottom of the poll. Following the election, the defeated candidates submitted a petition to the House of Commons alleging bribery, treating and intimidation by the two winning candidates and their agents.

Nationally, the Liberals won the general election returning Lord Palmerston as Prime Minister. The Dover case was heard in March 1860 by the House of Commons Election Committee chaired by Conservative Milnes Gaskell (1810-1873) and only appertained to the candidates. The Hearing was told that Dover’s population was 21,478 inhabitants of which 2,038 had the right to vote and included 819 Freemen, either resident in the town or living within seven miles. The general election had been called on 15 April and on the following day, it was announced that Churchward’s contract was to terminate in 1863. The accusers told the Hearing that Churchward then posted a notice in his Packet Yard, ‘begging all his men who had not promised their votes to do so. A meeting was held in the yard and the whole of the packet service pledged themselves to vote for the Conservative candidates.’

They went on to remind the Hearing of Churchward’s behaviour in the Plymouth election of 1852 (see Packet Service part II) when he had been found guilty of bribery. They went on to say that because the ballot was not secret it was known that all 53 of Churchward’s employees voted for the Conservative candidates, which amounted to undue influence. Further, they said, Churchward had given ‘carte blanche’ to one of his employees, a Mr Dodd to get as many votes as possible for Churchward’s candidates. Nevertheless, they emphasised, Dodd was not to say that the money Churchward gave him was for electioneering matters but for some other reason.

Dodd, in his evidence, confirmed this, saying that he understood the real meaning of Churchward’s request and had ‘bought’ approximately 500 votes paying, on average, £2 a vote. However, he was unsure that this was legal and therefore spoke to Churchward, who appeared to understand his consternation. Dodd then sought other employment and became a conductor on South Eastern Railway. The House of Commons Election Committee found bribery proven but as the successful parliamentary candidates, according to the evidence, were not privy to the illegal practices the election was not declared null and void.

Churchward was subsequently brought before a Parliamentary Committee when his conduct during the election came under the spotlight but he was able to defend himself. In his testimony, Churchward gave his home address as 21 Townwall Street, Dover and told the Committee that when he first won the Admiralty packet contract in 1854, it had not been ruminative. Nonetheless, it had enabled him to secure the French and Belgium contracts that made his business profitable. Out of these profits he was able to employ his men, open his Packet Yard and provide more employment.

Churchward admitted that the Admiralty contract was to expire in 1863 but the Belgium contract was to run until 1870 and he was sure of securing an extension to his French contract to the same date. He went on to say that if the Admiralty contract were extended for the same period he would be able to purchase another luxury packet ship. He admitted that the Post Office refused to extend the contract but on the 26 April he received written confirmation that the Admiralty agreed to the extension for which he would be paid £18,000 a year. The increase, he said, was to take into account increases in harbour rent and tonnage dues.

Since 26 April, Churchward told the Hearing, he had confirmed the order for the new steamer and poured more resources into the Packet Yard to keep his other vessels in good repair. These works along with his other shore staff and the crews of the steamers placed him in a position as a large employer of local labour. From this, he had gained a great deal of respect from those who he employed. Following Churchward’s testimony, evidence such as Dodd’s, was presented. Nonetheless, the Committee concluded that nothing substantial could be found against Churchward and that ‘he was a businessman who actions were dictate by the desire to achieve commercial success.’

On 18 February 1860 Churchward’s new steamer, the John Penn, left Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company, Blackwall for Dover. Like the Prince Frederick William, she was designed by James Ash and was similar in most respects; the only exception was that Penn’s of Greenwich engined the John Penn. This accounted for the new ship’s name for John Penn was the founder of the firm and was known for perfecting the oscillating cylinder engine. The John Penn covered the 89miles from Blackwall to Dover in 5-hours 7-minutes. On arrival she went straight into service taking 220 boxes of Indian and Australian mail, weighing just under 6-tons, to Calais. Under Captain Smithett, the crossing took 1-hour 23-minutes and Churchward was on board along with Mr Knight the superintendent for the South Eastern Railway (SER) who was to deal with the French railway arrangements.

Churchward won the French contract to run until 1 April 1870, with one caveat, he was required to have a French partner and he appointed a M. Clebetteal & Co of Dieppe. To help avert another catastrophe, in 1859, the Calais authorities introduced the Poste, a tender for carrying the mails when the tides were too low to use the harbour. With the new ship and the contract firmly under his belt, Churchward, along with Smithett, introduced another innovation to the Packet service – the training of youths to become officers. To be accepted the boy was required have a good knowledge of seamanship, leadership abilities and expected to be literate. On completion of the training, the boy was accepted as ship apprentice without premiums (See Sea Cadets).

European Royalty crossing the Channel showed a preference for Churchward’s luxury packets ships and in September 1860, the Grand Duke Michael of Russia (1832-1909), and the brother of Czar Alexander II (1855-1881), along with his wife and a retinue of 25 distinguished persons made the crossing. They arrived aboard Prince Frederick William and dined at Ship Hotel before travelling to London and thence to Torquay. The ship was in charge of Captain Pittock but on Royal request, Captain Smithett attended to the party and travelled to Devonshire with them. For this, Smithett was given a costly ring. A few days before, Smithett had escorted to France the Grand Duchess Marie of Russia (1819-1896), again aboard Prince Frederick William and was given a heavy gold chain for his trouble. On 18 July 1861, Prince Frederick William of Prussia arrived in Dover, but not on the ship named after him but on Vivid (I), with Captain Smithett at the helm. The following year, Queen Victoria (1837-1901) knighted Captain Luke Smithett!

In the town, Churchward was also beginning to be held in esteem and in 1861 was asked to arrange the Regatta. This was held on the same weekend as the installation of the Prime Minister, Viscount Palmerston as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. Smithett joined Churchward’s team and between them they were determined that the Regatta would be the best ever. The new Lord Warden attended, to see yachts from all around the kingdom in Dover Bay. Not only were there several classes of yacht races, there were races between four-oared regatta-built galleys, skiffs, pleasure boats and fishing vessels. In the evening, there was a grand ball and a magnificent firework display.

By 1861, the second stage of the Admiralty Pier was almost complete giving 1,539 feet of quay space. This was two years before, Churchward’s packet contract was expected to cease in 1863. Because of this, SER had entered into an agreement with the Admiralty that allowed trains to pass directly onto the new Pier for which they had contributed £3,000 towards modifications. When the modifications were completed a new railway line continued from SER’s Town Station on a curve to a new station the new Pier. Adjacent was the quay where ships would berth. In October 1861, SER started running trains on the Admiralty Pier but Berth 2 was designated strictly for the sole use of Churchward’s Packets and only mail trains were permitted to use that section of railway line. With the new berthing facilities, Churchward was quick to advertise the ease by which passengers could transfer from train to ship and visa versa. However, the parliamentary inspectorate that checked out the ships of the tendered packet contracts cast doubts on the Ondine II. The inspector concerned, reported that she was of ‘doubtful efficience,’ and recommended that she should be withdrawn from packet service. The Ondine II was only used by the Churchward enterprise as a relief ship but in that capacity she was needed and Churchward did not have the resources to replace her. Pressure was on Churchward with the Ondine II being withdrawn from service in February 1862. She was then used only for excursions until she was sold. The Ondine II was later broken up in 1889.

Otherwise, everything was beginning to augur well for Churchward with his business receiving high commendation in April 1862. That month, much to the surprise of the government and the national media, Earl Charles John Canning (1812-1862), arrived without ceremony on the Vivid I from Calais. Captain Smithett was master and on recognising Lord Canning, telegraphed Churchward before the ship left port. Canning was the former Governor-General of India holding that position during the Indian uprising of 1857 and was highly thought of in Britain. On arrival at Dover, Churchward ensured that Lord Canning would receive the welcome he deserved and a gun salute was fired as the ship came into the Bay. On Admiralty Pier, Mayor John Birmingham and senior military personnel from the garrison met Lord Canning but it was evident that his Lordship looked worn and tired. In fact, he had returned home because he was very ill and died two months later.

It was a morning towards the end of 1862 when Churchward was reading the national papers that he received a bombshell! The Liberal Post Master General, Edward John Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley (1802-1869), was advertising for tenders for the Dover-Calais and the Dover-Ostend packet contract from 21 April 1863! Churchward immediately contacted his London solicitors, who wrote to the Post Office and Admiralty as well as putting an advertisement in the papers. It was made clear that in their opinion Churchward held the contracts until the spring 1870 and that they were legally binding. The situation was discussed in Parliament and it was generally agreed that Churchward and his legal counsel were correct. However, in the House of Lords, on 17 May 1863, the Solicitor General, Roundell Palmer, 1st Earl of Selborne (1812-1895), drew attention to the date of the contract, 26 April 1859. This, he said, was on the eve of the general election and even though the Liberal government had retained power, the government, as a body, had changed. He reminded the House that at the 1859 election the two incumbent (Liberal) candidates for Dover, against the national tend, had lost the election. This, he said, had subsequently led to an inquiry into bribery allegations in which Churchward’s name featured. Selborne did not mention the outcome of the second hearing but finished by stating that ‘upon the merits of the case, the House would be justified in repudiating the contract, though satisfied that the Members of the government of the day acted on public grounds.’ This was upheld by 173 votes to 163. Two days before, public notice was issued stating that Churchward would not be paid for packet services provided by his company from 21 April to June 1863.

Churchward retaliated by having his English employees meet the SER mail trains and formally ask for the French and Belgium mails. When the officials refused to hand them over, Churchward’s employees left. Shortly after, his Belgian employees would go to the train and on showing that they represented the Belgian government packets, the mails would be handed over. Churchward was going to apply the same tactic to the French mails but instead he just brought mails back from France as required by his French contract. At the same time, through his Belgium assistant, he offered that take the British mails for France to Ostend and to arrange for them to be transported to Calais by train. This was agreed and carried out. Then, in early July he sent the Post Master General a bill for £4,000 for carrying British mails for Belgium and French on his Belgium packet ships but the Postmaster General’s office refused to pay. The London. Chatham and Dover Railway Company (LCDR) won the new British packet contract and were paid £13,000 a year. It was ratified 1 May 1863 and came into effect on 20 June 1863.

On LCDR winning the contract, Churchward started legal action against the government and resulted in presenting a Petition of Right. The Hearing for this was at the end of 1865 in the Court of the Queen‘s Bench at Westminster before Justice John Mellor (1809-1887), Justice William Shee (1804-1868) and Robert Lush (1807–1881). There it was heard that the Attorney General (1863-1866), the recently promoted Roundell Palmer, 1st Earl of Selborne, had demurred saying that Churchward had no valid claim against the Crown as no valid funds were provided by Parliament for the purpose of carrying out his alleged mail contract. That by the 1860 Act of Appropriation, when it was returned to the Post Office the Admiralty ceased to have control of the mail packet service. The Act did leave the Admiralty with the right to make contracts over the use of the vessels employed and check out their sea-worthiness but not the actual carriage of mail. Churchward’s council argued that the 1860 Act had been ratified after Churchward had been awarded the contract by the Admiralty in 1859. Nonetheless, the Court upheld the arguments put forward by Attorney General Selbourne.

A year later, following a general election when the Conservatives came to power, Sir William Bovill, (1814-1873) was appointed the Solicitor General. He came to the same Court on behalf of the new Attorney General, Sir John Rolt (1804-1871) and Churchward. This was to ask for a move to strike out issues of fact in the earlier judgement, arguing that they created the precedence that the payment for Government contracts only applied to services delivered not for services promised. Therefore, when a contract is summarily terminated the contracting company has no remedy. However, it was agreed to overturn the ruling on the Petition of Right, Churchward would be required to bring a Petition of Errors. Shortly afterwards Churchward received £4,000 for services rendered between April and June 1863. However, it would appear that Churchward did not submit a Petition of Error for the earlier judgement was cited in similar government contract cases for a long time afterwards.

Following LCDR’s contract ratification in 1863 Churchward agreed to transfer his steamboats, offices and packet yard for £120,000 to the Railway Company. Paid in instalments of £7,000 until 1870, the payment was made up of cash, preference shares and bonds bearing 5% annual interest. LCDR also agreed to pay Churchward an annuity of £800 per annum to 1870 for the Belgium contract. For the French contract, Churchward and his French appointee, M. Clebetteal & Co of Dieppe, were to receive 30% of LCDR’s return and in 1863 this was £1,800 with Churchward taking the larger share. Churchward’s steam packets at the time of agreement were:

The former Onyx, renamed Vivid II and was sold to LCDR.

The former Garland changed to L’Alliance to comply with the French contract sold to LCDR. They sold her on to the Confederate States of American for use as a blockade-runner and she was scrapped in 1867.

Prince Frederick William sold to LCDR and remained in service until 1878.

John Penn sold to the Belgium packet service in 1862, before Churchward made the deal with LCDR, and renamed the Perle. She was later sold on to the French packet service retaining her Belgium name.

Jupiter sold to LCDR who sold her to the Confederate States of American as a blockade-runner but was lost, on her way over, in the Bay of Biscay.

Churchward then turned his energies and attention to local matters. The 1865 general election in Dover was almost as vicious as the one of 1859 but with four new candidates. They were William Coutts Keppel, Viscount Bury (1832-1894) and Thomas Eustace Smith (1831–1903), a shipping magnet both nominated by the Liberals. The Conservatives nominated Major Alexander George Dickson (1834-1889) and Charles Kaye Freshfield (1808-1891). Dickson’s name had been put forward by senior Conservative Alderman John Birmingham and Freshfield by Churchward. Throughout the campaign, Churchward used his journalistic skills to extol the virtues of both the Conservative candidates to the detriment of the Liberal candidates. Although the Conservative vote was less than in 1859, Dickson won with 1,027 votes, Freshfield 1,012, Bury 907 and Smith 901.

In August 1866, Churchward was appointed Justice of the Peace (JP). Shortly after a motion was passed in the House of Commons to amend the Act to state that ‘all persons in the Commission of the Peace who had been proved to be connected with corrupt practices should be removed.’ By January 1867, questions were being asked in Parliament as to why Churchward still held the position of JP as the Commons had found him guilty of bribery in the 1852 election. After much debate, in March 1867, a vote was taken to amend the Act in order to remove Churchward and anyone else found guilty of corrupt practices from becoming JPs. The motion was defeated by 161 to 141.

Following his arrival in Dover, Churchward had used his journalistic skill in the Dover Telegraph and the Dover Chronicle. William Batcheller had started the Dover Telegraph in 1833 and William Prescott of Guston founded the Dover Chronicle in January 1835. By 1843, both papers had a joint yearly circulation of 53,000. In October 1868, the Dover Telegraph was put up for auction and Churchward bought it having already acquired the Dover Chronicle. Although only a relatively small circulation, the two papers gave Churchward a strong base in which he used to make or break local politicians. He very effectively created a small press empire, which he did not relinquish until September 1884. The only opposition was the Dover Express founded in 1858.

Probably as a reaction against the parliamentarians who wished, but failed, to remove him as a magistrate, Churchward decided to become Dover’s chief magistrate. At that time the Mayor held the position and Churchward was not even a councillor! On 1 November 1867, he was elected as one of the representatives for Castle Ward, which covered a large area on the east of the town up to the river boundary. Hardly had the count finished when it was announced that he should be Dover’s next Mayor. At the time, the mayoral year started approximately two weeks after the local elections that took place in November.

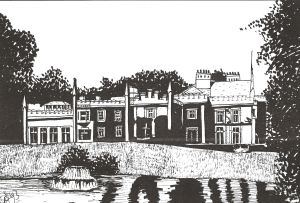

Brook House Maison Dieu Road 1988, owned by John Birmingham who was to hold a lavish dinner there had he been elected Mayor in 1867. Dover Museum

Albeit, the decision on the next Mayor had already been made and that was the Conservative stalwart, John Birmingham. Birmingham had taken over the prestigious Ship Hotel in 1844 and in 1853 was appointed as manager of the new and grand Lord Warden Hotel by the owners, SER. A Conservative councillor for the Town Ward, Birmingham was elected an Alderman in 1858 and two years later, he was unanimously chosen as Mayor and re-elected the following year. In October 1867, he had bought Brook House and following his anticipated election as Mayor, he was going to hold a lavish dinner there for all the members of his Party. Churchward relished the contest and the outcome was just as he liked – a close call with Churchward beating Birmingham by 13 votes to 11.

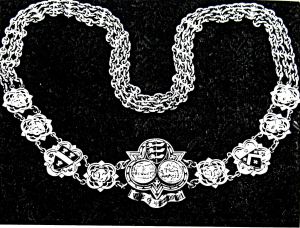

Chain and Badge of Office of the Mayor of Dover presented to the town by Dover’s Recorder Sir William Bodkin in 1868

A few weeks later, as Mayor, Churchward received a letter from Sir William Bodkin (1791-1874), Dover’s Recorder. Bodkin said that he was, ‘desirous of offering some acknowledgement of the great kindness with which he had been treated by the authorities at Dover during his long connection with them and that it was his intention to present an official chain to be worn by the Chief Magistrate of the Borough during their respective terms of office, for ever.’ Bodkin’s present was a beautiful piece of workmanship composed of three chains of oval links, six circular links cast and pierced with Lion marks with the badge of the trefoil Arms of Dover. At the January Quarter Sessions, which as Chief Magistrate Churchward presided, the presentation was formerly made by Sir William Bodkin placing the chain around Churchward’s neck. The valuable decoration has since that time been worn by the Mayor’s of Dover at Council meetings and on all special occasions.

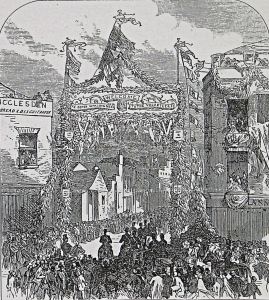

Castle Street, Welcoming Volunteers to the Review – Illustrated London News 04.05.1867. Dover Library

Churchward undoubtedly wore the new chain of office to the Volunteer Review that took place over the Easter Weekend of 1868. He had been actively involved in the Cinque Ports Volunteers, eventually taking command from when he first arrived in Dover. He had also participated in the establishment of the Dover Company of Rifle Volunteers allowing the pattern department room of his Packet Yard to be used for drilling. Churchward relinquished his position in the Cinque Ports Volunteers in 1864, passing the command to solicitor Edward Knocker the then Town Clerk. On 5 May 1868, following a unanimous election, the post of Town Clerk went to Edward Knocker’s son, Wollaston Knocker who held the post until his death in 1907.

Shortly after Wollaston Knocker took up post, 19-year old Thomas Wells was accused of murdering LCDR Dover Priory stationmaster Edward Walshe. For the initial Hearing he was brought before Churchward, as Chief magistrate. Wells, a carriage cleaner, had been reproached by Walshe for firing a pistol on Company property while on duty. A meeting was held that included the railway superintendent, Henry Cox where it was obvious that Wells did not think he had done anything wrong. Wells showed resentment at being reproached and Walshe asked him to leave the room for ten minutes to reflect on why both he and Cox thought otherwise. A few minutes later, while Cox was sitting writing up the report with Walshe standing besides him, Wells flung open the door and fired his gun at the stationmaster‘s head, killing him. Churchward remanded Wells and soon after the inquest was held. The town’s coroner, William Henry Payn presided and the jury returned a verdict of ‘Wilful Murder.’ In August 1868, Wells was hung at Maidstone Prison, the first person to be convicted of murder following the enactment of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act of 1868 that put an end to public executions.

On retiring as Mayor in November 1868, Churchward was elected to the Aldermanic Bench, a position that he held until 1874. Because of his Mayoral commitments Churchward did not have the time to play an active part in the general election of 17 November 1868. Major Dickson topped the poll but Freshfield came third. Second was one of the Liberal candidates, lawyer George Jessel (1824-1883) who impressed Churchward with the vigour he fought the election. During the election, Jessel had made a point of denouncing bribery and afterwards a petition was sent to the House of Commons alleging such practices. Dickson and Churchward were both named but the evidence was slight and the case was dismissed.

The recently knighted Sir George Jessel was appointment Solicitor General in 1871 and a bye-election was called. Jessel stood and the Conservatives nominated an Edward Barnett. Churchward had made it clear that the election was nominal and not to field a candidate but this had been ignored. In his newspapers, Churchward declined to support Barnett and Jessell won. That night rioters smashed the windows of Jessel’s supporters homes en route from Market Square to the Pier District. There they vented their fury on the Dover Castle Hotel, Clarence Place in the Pier District where Jessel had been staying during the election.

Churchward was vitriolic over the incident and the Conservatives retaliated by publishing a new local paper, the Dover Standard. The following year, on Jessel’s appointment as Master of the Rolls, another bye-election was called. This time Barnett, with the full backing of the Dover Standard, won, This time Barnett, with the full backing of the Dover Standard, won, his Liberal opponent was James Staat Forbes (1823-1904), the general manager of LCDR and member of the Dover Harbour Board. This was the first Parliamentary election in Dover under the Ballot Act 1872 requiring a secret vote by means of the ballot box. However, on the day of the election rumour was rife that two members of Forbes’ committee had been found guilty of bribery. The accusers were Hilliard – the chairman of the Conservative committee and Evan Hare – Barnett’s agent. The alleged guilty men were ex-Mayor and Magistrate, Richard Dickeson and councillor Robinson. They immediately took legal action and Hillard and Hare were found guilty of libel. The Dover Standard did not report the proceedings but Churchward had a field day in his papers!

The French Calais-Dover packet contract was part of the deal between Churchward and LCDR and this was due to expire in 1870. By 1868 it was earning more than £7,000 a year and in the terms of the agreement, Churchward and Clebetteal were receiving 30% just over £2,000. To ensure that it remained in their name, Churchward and Clebetteal saw the French government’s packet official in 1868. They were assured that on renewal the contract would be in their names for a further 10 years. In 1870 the Kearsney Abbey estate, which included the Abbey, Kearsney Manor, Bushy Ruff Mill and land adjoining, but not Bushy Ruff House, came up for sale and on the strength of the French contract renewal, he purchased the estate for £10,500.

For the first few years, Churchward lived in Kearsney Abbey with his wife, Annabelle née Carrington, whom he married in 1841 and four of his six children. He was attended by a full retinue of servants under the charge of an imposing butler named Sutter Sulliman from Persia. Political upheaval in France negated the promises made over the French Calais-Dover packet contract and in 1875, Churchward put Kearsney Abbey on the market. He, Annabelle with faithful retainer Sulliman moved into Kearnsey Manor. Kearsney Abbey was sold to F Lyon Barrington but when he died in 1877 the Abbey was bought by John Henry Loftus 4th Marquess of Ely (1849-1889).

The Belgium government advertised a 15-year packet contract in 1871 to carry mails between Antwerp and New York. Churchward formed a consortium with Frank Clarke Hills (c1808-1892), Lord Alan Spencer Churchill (1825-1873) and Peter Rolt. The first two, like Churchward, were directors of the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company. It was proposed that ships built by the company would carry the mail. An American consortium also applied but they were not as fully prepared such that Churchward’s consortium won. The contract was for a fortnightly service and the requisite vessels were to be 2,500-3,000 tons. Arrangements included a call at Dover harbour. It is unclear whether the consortium successfully complied with the contract for it was withdrawn in 1874 and given to the American rival, Clement Griscom (1841-1912) of the Red Star Line.

In January 1872 Churchward introduced the highly acclaimed shipping and harbour engineer James Abernethy (1814-1896), to a town council meeting chaired by the Mayor of Dover, Richard Dickeson. The subject was the Harbour of Refuge and the meeting centred on the possibility of using the Admiralty Pier as a western arm of a proposed harbour, enclosing 340 acres of sea space. Throughout that year, this was the main subject of discussion and in August, at a DHB Board meeting presided over by Deputy Chairman Steriker Finnis and including Dover representatives Samuel M Latham and John Birmingham, together with the railway companies representatives, James Staat Forbes and C W Eberall, the proposal was agreed.

Sir Andrew Clark was to build the proposed harbour and in May 1873, Churchward in the Dover Chronicle reported that the proposal had been sanctioned by a recent Dover Harbour Act. In July 1873 the Admiralty ship, Porcupine, arrived in Dover to undertake the survey for the planned new Harbour of Refuge. The proposal was eventually started with the building of the Prince of Wales Pier. Then, in May 1895, when the Pier was about three quarters built the Admiralty announced that they were going to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy and the Admiralty harbour we see today was constructed.

Churchward was elected a councillor in November 1875 as a representative of the Pier Ward, retiring in 1878. The year before, the popular Castle Ward incumbent, William Adcock was asked to stand for the Conservatives in the Liberal stronghold of Town Ward against Richard Dickeson and Philip Stiff. Adcock was thrashed. As compensation, Churchward arranged for Adcock to be nominated for the office of Alderman and he was given a full term – six years. However, in November 1879 the Conservatives lost their majority in the council and Adcock his seat. At the time, the main local issue was the extension of the town hall – now the Maison Dieu – and in particular how it was to be paid for. The Conservatives were not keen on a large extension, as this would require a large government loan, though the Liberals, under Dickeson took the opposite line. In 1881, Liberal Lord Frederick Cavendish (1836-1882), then the Secretary of the Treasury, wrote to the council giving government consent to borrow the money and what became Connaught Hall was built.

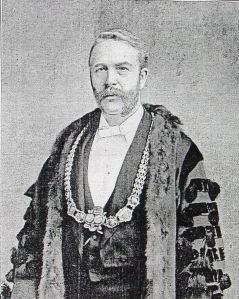

William Adcock, Mayor of Dover 1895-96 wearing the Mayor’s chain given by Sir William Bodkin. Dover Library

The Liberals held the majority in the Council for four more years but under Churchward’s guidance, the Conservatives gained one seat or more every year. In November 1885, they were of a sufficient strength to elect a Mayor and Churchward ensured that Adcock was elected to the position. In the meantime, the 1880 general election had been won by the Conservative candidates but by a diminished majority. At the next general election, owing to the 1885 Redistribution of Seats Act, there was only one seat at Dover and this was fought for vigorously. Major Dickson again headed the poll with 2,066 against the Liberal, Murray Lawes of Old Park with 1,418 votes. Following the dissolution of Parliament the following year Major Dickson, was the only candidate and it was the first parliamentary election in Dover since 1830 that had passed without a contest.

The 1887 local election was a political embarrassment for Churchward due to the lack of suitable candidates. In the end, he stood in the maritime Pier Ward with a Mr Bussey as the fellow candidate. Bussey was so out of touch that he argued against Churchward and the other candidates over the proposed Harbour of Refuge! This cost Churchward the election and he was angry. Albeit following the death of Major Dickson, Churchward fully supported Conservative George Wyndham (1863-1913) who won the parliamentary bye-election of 1889 and held the seat until his death.

In 1882, Churchward split his Kearsney estate selling the land to the north of the Abbey and west of the Manor. There Kearsney Court was built and later Edward Barlow, Managing Director of Wiggins Teape’s paper mills resided. Barlow made significant alterations that included laying the formal gardens that eventually became Russell Gardens. However, in the spring of 1884, Churchward’s wife, Annabelle died aged 72 and in September of that year, he disposed of the Dover Telegraph and the Dover Chronicle. The following year in London, where he bought a house, Churchward married Elizabeth Durrant of Ipswich, some 30years his junior.

Churchward returned to Kearsney Manor and Dover politics, occupying the positions of Chairman of the Dover Highway Board and Rural Sanitary Authority. When Kent County Council was constituted in 1889, Churchward was elected a county councillor then following a serious accident he withdrew and took a long vacation. In 1894, Churchward was appointed chairman of the Dover Rural Council, which was formed that year and by virtue of the new Act became a county Magistrate. The year before, he sweetened his relationship with his former major publishing rival, the Dover Express, by asking the Board of Guardians to change the day of their meetings to ‘make it more convenient ‘ for the debates to be reported to the local newspapers. However, the accident, chronic gout and age were taking their toll and in 1899 he and Elizabeth decided to move to their London home where he died on 2 January 1900 age 81. Churchward’s body was returned to Dover and he was buried in St Peter and St Paul’s Churchyard, River, next to Annabelle, his first wife.

Packet Yard Snargate Street during demolition 1991-92 Joseph Churchward’s most enduring legacy to Dover. Budge Adams Collection – Dover Museum

Although Churchward’s success as the holder of the Packet contract is questionable, he did leave Dover two great legacies – the Packet Yard and political influence. Taking the latter first, although he was a Conservative and assumed the role of puppet master, through his two papers he did not let party politics interfere with his judgement. In consequence, Churchward laid and built upon the foundations that by the end of the century made Dover one of the top 10% wealthiest English towns. Churchward’s other legacy was the Packet Yard at 91 Snargate Street and was more enduring, The Yard continued to expand, becoming the largest maritime support service in the town and was later renamed the Dover Marine Workshops – owner A & P Appledore. It closed for the last time on 24 June 1991 when the business was transferred to Poulton Close Industrial Estate, Buckland. There the staff clocked in for work Tuesday 25 June 1991. The demolition of the Snargate Street Packet Yard began on Monday 1 July 1991 and was completed by the end of the second week of August that year. The contractor for the work was Norwest Holst with Dover Demolition Company.

Packet Service IV – London Chatham and Dover Packet Service 1863 – 1874 continues

- Presented: 5 August 2015