The London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company (LCDR) won the potential lucrative packet contract for carrying mails, both official and private, across the Channel from Dover to Calais in 1863. Two years earlier the Company’s railway lines reached the town and the company had built the Harbour station on the side of harbour near the base and east of the Admiralty Pier. To there, they planned to carry freight from a huge railway goods receiving complex they planned to build near their London terminus at Victoria railway station on the banks of the Thames (see London Chatham & Dover Railway part I). The freight would then be loaded onto cargo carrying vessels to the Continent and to all over the world. The only railway company, other than LCDR, to lay a railway line from London to Dover was the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) who had opened their line on 7 February 1844. Their terminus was the Town Station, to the west of the Admiralty Pier but about a mile away from Dover’s town centre.

Three years after SER had opened its railway terminus, the building of the Admiralty Pier commenced. At the time the Pier was planned to be the western Pier of a large Harbour of Refuge and Dover had great hopes that the new harbour plus the new railway line would give the town the economic boost it needed. However, in 1842, SER had bought the derelict Folkestone Harbour with the intention of turning that into their main passage port to the Continent and in 1850 they had built the North Kent Line as far as Strood. It was during this time, in 1845, that the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway was formed and they planned to lay a railway track from London Bridge Station to Ramsgate and Margate. Also in 1845, the Canterbury and Dover Railway Company was floated and this was to provide a connection at Canterbury with the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway from Dover.

East Kent Railway’s Lines in East Kent showing the line to Thanet and to Dover and Dover Harbour. Dover Museum

In 1852, the London, Chatham and North Kent Railway amalgamated with the Canterbury and Dover Railway to form the Strood, Canterbury and Dover Railway Company. They proposed a 44-mile line from Dover to join the SER London-Strood line at Strood but when the Company applied to parliament for permission, SER vehemently objected. Thus, in September 1852, the Company was dissolved but reconstituted, in September 1852, as the East Kent Railway Company, (EKR) and ratified in 1853. By 1860 it connected Rochester to Canterbury.

Joining of Dover to Canterbury by rail was the obvious next step and SER, which had objected to EKR’s projects thus far, offered no resistance. This was regardless that EKR had stated that they planned that their railway would go under the Western Heights and to Dover harbour close to SER’s Town station. In their parliamentary application EKR stated that they would build a station next to the harbour and called Harbour Station, from where they would run a fleet of cross Channel passage ships – they carried passengers and goods but not official mail.

This was given Royal Assent in 1855 as the East Kent Railway (extension to Dover) Act. The construction of the Canterbury-Dover line was started and EKR successfully changed their name to the London Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR). The second stage of the Admiralty Pier was on the way to being completed and LCDR, in their evidence to parliament for the Dover section, had suggested running a track along the Pier where they would build a station. SER had previously sought a similar agreement so reiterated it, but as the Pier was not completed neither companies were given permission.

At the time, EKR’s ambitious plan was not the carriage of passengers and goods across the Channel and they had not even given any thought in trying to gain a packet contract to carry posted and official mail and parcels to and from the Continent. They planned to create a major freight terminal at Dover harbour for shipping goods to and from abroad in connection with a massive depository on the banks of the Thames in central London. From the outset SER treated the ambition as ridiculous and therefore felt that their cross Channel passage service had the potential of being threatened by LCDR’s activities. In 1860 EKR obtained powers to build a railway from Rochester to London to create a direct main line to the north bank of the Thames and close to their proposed depository and station at Victoria Street, Westminster.

In the same year that LCDR arrived in Dover, 1861, the Harbours and Passing Tolls Act came into force with the aim of facilitating the Construction and Improvement of Harbours by authorising Loans to Harbour authorities. The Act abolished Dover’s Passing Tolls and embodied within it a new constitution that led to the Harbour Act of the same year. This abolished the Harbour Commissioners that had been in existence since 1606, replacing them with the Dover Harbour Board. Like the Commissioners, the Board was presided over by the Lord Warden at the time (1861-1865), Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784-1865). The new Board consisted of five members, two of which were representatives of Dover Corporation, one represented SER, one the Board of Trade and one the Admiralty. The latter was Captain Jeffrey Wheelock Noble RN (1805-1865), the superintendent of Pilots and following his death on 21 March 1865, by Steriker Finnis (1817-1889). Following the opening of the Harbour Station, LCDR demanded that they too should have a representative, which was agreed, making two representing the Railway Companies making a total of six members.

The new Constitution allowed for three ex-officio members, they were the Register (not Registrar) – at the time this was local solicitor James Stilwell (1828-1898); the Chief Engineer – Rowland Rees (1816-1902) and Harbour Master – Richard Iron (1819-1883). The new constitution not only changed the makeup of the Board but it also deprived it of its prime source of income, that of Passing Tolls – at the time worth £10,000 a year. The Act did allow, subject to parliamentary approval, debenture flotations and for arrangements to be made with the railway companies to raise finance for harbour improvements. A later court ruling gave priority of berthing to the contributory railway companies.

Admiralty Pier with a London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company train and packet ship in the Bay. South Eastern Railway’s Lord Warden Hotel on the right. Dover Museum

By 1863, 1,675 feet of the Admiralty Pier had been constructed and the quay against which ships berthed on the east side was 1,539 feet in length. The best position was Berth 2 and this was designated for the sole use of packet ships belonging to the Royal & Imperial Mail Steam Packet Company, which held most of the packet carrying contracts to and from the Continent. The Company owner was Joseph George Churchward (1818-1890) and his packet ships left Berth 2 for Calais in the morning and evening. The schedule tied in with SER mail trains from London and for this reason, from October 1861, SER had been allowed to lay and run along a line on Admiralty Pier to Berth 2.

SER had expected to retain the mail train contracts and planned to put in a bid for the packet contract to Calais when that came up for renewal in 1863. They already held the Folkestone – Boulogne contract and in order to further their Calais bid, SER moved two of their cross Channel ships, the Princess Clementine and the Princess Maud, to Dover. They also paid to have a covered walkway erected between the Lord Warden Hotel, which they owned, and their Town Station. However, when Churchward’s contract was extended, in April 1862, to 1870 SER moved the two ships back to Folkestone.

To save the Government money, the Dover- Calais Packet contract had been privatised in 1854 and Churchward had held it since that time. To ensure his vessels were in working order he had rented the former Admiralty packet yard for £120 a year but had increased the number of workshops there without the permission of the owners, Dover Harbour Commissioners. Just prior to the reconstitution of 1861, they demolished the buildings and evicted Churchward. During LCDR’s excavation of the lower (west) end of Snargate Street for their tunnel from Dover Priory railway station to the harbour, they demolished a number of buildings. This created a vacant plot, which Churchward had bought from LCDR to build his own Packet Yard.

Tiger Class Swallow 2-4-0 engine designed by William Martley and built by Peto, Brassey & Betts 1861. Wikimedia Commons

For their envisaged cargo shipping company LCDR had floated the subsidiary company, LCDR Steamboat Service. Irish locomotive engineer William Martley (1824-1874) was appointed LCDR’s Locomotive Superintendent. In 1861 he designed the Tiger Class Swallow 2-4-0 engine built by Peto, Brassey and Betts of London that was not withdrawn from service until 1904. At the same time, Martley established the Longhedge railway works on Stewarts Lane, Battersea. This opened in 1862 but due to money being spent on new railway lines, the work was mainly repairing and rebuilding a variety of engines, including the specially ordered Hawthorn engines. In 1864, having possibly been head-hunted by Forbes, the General Manager of LCDR, Martley was entrusted with the organisation and supervision of the company’s shipping line.

In the summer of 1862 LCDR, introduced a midday cross Channel passage service from a quay they had created close to Harbour Station. This tied in with the timing of their ‘boat train’ from London. For this reason, the front of Harbour Station faced the quay. Prior to Martley taking up the post, LCDR had ordered the paddle steamers:

Maid of Kent (1) was designed by Royal Navy Lieutenant James Morgan, the Company’s newly appointed naval architect and marine engineer.

Paddle steamers Maid of Kent and the Samphire tied up to the London, Chatham & Dover Railway quay at the west end of the tidal basin. Dover Museum

She was 335gross tonnage, built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar and her 2×80 horse power diagonal oscillating engines, with pistons 50inches in diameter with a 3feet9inch stroke, were built by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co. The paddles were feathered and the boilers were tubular. The Maid of Kent, along with her sister ship, Samphire, had private cabins described as ‘loft and capacious’ and thus they were the first cross-Channel ship to have such luxuries. The ship’s two rowing/lifeboats were fitted with the Charles Clifford’s method of lowering ships’ boats and designed in 1852. Popular with the Royal Navy, this was the first time this design had been used on a non-Naval ship and Morgan ensured that all the ships he ordered had the Clifford design lifeboats. The Maid of Kent was launched at the same time as the Samphire but during their joint trial to Calais from the Thames the weather deteriorated and the Maid of Kent suffered damage to both paddles and paddle boxes. When LCDR won the Dover-Calais packet contact, the Maid of Kent had new, more powerful engines, installed.

Samphire – designed by Lieutenant Morgan and built by Messrs Money, Wigram & Co of London in 1861, she was originally named Shakespeare. The Samphire was a 330gross tonnage iron paddle steamer and engined by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co of Blackwall, London. Except for the slightly less tonnage she was identical to the Maid of Kent. When Churchward’s Dover-Calais packet contract was renewed, LCDR loaned him the Samphire and on Tuesday 15 May 1862 she made the fastest crossing to Calais. Taking 1hour 23minutes and 1hour 18 minutes for the return journey her mean speed was 16.265nautical or 18.825 statute miles per hour.

Petrel was launched in 1862, designed by Lieutenant Morgan and built by Messrs Money, Wigram & Co of 503gross tonnage and had 2×120 horse power, simple oscillating engines built by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co. At the suggestion of Admiral Sir Baldwin Wake Walker (1802-1876), the surveyor for the Royal Navy (1848-1861) under whom Lieutenant Morgan had served, she was fitted with a bow rudder. Walker was notable for his wooden hulled wrought iron-clad battle ship the Warrior that was not so vulnerable to gun-fire as the Royal Navy’s iron ships of that time were. The Warrior can now be seen at the Portsmouth Naval Dockyard Museum. On 29 June 1862, the Petrel made her trial run to Calais with Walker on board and she made the crossing at an average speed of about 18 statute miles an hour.

Scud was an iron paddle steamer of 482gross tonnage launched in 1862. She was built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar with 2×120 horse power, simple oscillating engines by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co.

Foam an iron paddle steamer of 497gross tonnage launched in 1862. She was also built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar and was fitted with a bow rudder similar to Petrel. Her 2×120 horse power, simple oscillating engines were by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co.

Before SER moved their two ships back to Folkestone, they suggested to LDCR that instead of having a trade war, the two companies should form a cross Channel passage cartel. Three directors of LCDR, George Francis Robert Harris the 3rd Baron Harris (1810-1872), Sir Cusack Patrick Roney (1810-1868) and Charles Jones Hilton (1809-1866), met the directors from SER headed by Sir Edward Watkin (1819-1901), at the Westminster Palace Hotel. There, SER proposed that they would run the cross Channel service between Folkestone and Boulogne while LCDR would cover the Dover-Calais crossing. That all railway receipts from all stations in a six-mile radius of Charing Cross railway station, London via Dover, Folkestone and any other port that might be used along the coast between Margate and Hastings for the Continent would be divided between them.

As SER was the established Channel passage company they would have 70% of the receipts and LCDR, as the new comer, 30%. SER also suggested that the Agreement should run for 10years when the ratio that would, by that time, have become incrementally equal. Thereafter, if they wished to continue, then separate contracts could be drawn up. LCDR were well aware that SER costs would always be lower than theirs because of Dover Corporation’s Coal Dues – a local tax for the carriage of coals through the town even if they were brought in by sea. Albeit, as LCDR planned a major cargo terminal at Dover not primarily the provision of a passage service, they readily agreed and it was appropriately named the Continental Agreement.

In December 1862, it took everyone by surprise to see an advert for the Dover-Calais contract from June 1863. Churchward immediately took legal action over the sudden change in decision (see Packet Service Part III). LCDR’s General Manager, James Forbes, approached the Company’s Board of Directors and suggested that LCDR put in a bid and also to provide the mail trains. At first they were reluctant and approached SER and it was agreed that they would put in a combined bid, whereby SER would provide the mail rail service and both companies would provide the mail ships and share the revenue from the latter pro rata. Days before the decision on who should be awarded the contract, Forbes put in another bid solely on behalf of LCDR for the Dover-Calais packet contract with no mention of how the mail would be transported between London and Dover.

Just before the closing date of the Dover-Calais packet contract, Forbes, on behalf of LCDR, put in a bid to run the service from London to Calais via Dover of £6,000, thus under-cutting the SER-LCDR’s joint bid. Forbes, in his submission pointed out that the Dover – Calais sea route was shorter than Folkestone – Boulogne and that SER, as the dominant partner, would promote the Folkestone-Boulogne route, which was tidal and therefore irregular. Forbes was successful and LCDR’s full packet contract, from London to Calais, came into effect on Saturday 20 June 1863!

James Staats Forbes (1823-1904) of the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company. Vanity Fair 22 February 1900. Evelyn Robinson

James Staats Forbes, had trained as an engineering draughtsman before joining the Great Western Railway. He eventually became the goods superintendent at Paddington railway station and then joined the Dutch Rhenish Railway. He was effectively head-hunted by EKR and was appointed General Manager by LCDR in 1861. Forbes was later described as charming, eloquent and a brilliant negotiator but at this time, the Board members were angry. To them Forbes was a mere employee who had the audacity to tell them that LCDR was not in a financial position to support their grandiose idea of the port of Dover becoming an international freight terminal. Nonetheless, they did accept Forbes’ argument that, for the short term, LCDR should concentrate on the Channel packet contract to Calais.

LCDR Board members then expressed concern over the Continental Agreement, as they recognised that as it stood it was not in LCDR’s favour. Forbes stated that they should consider rescinding the Agreement but the Chairman, George John Watson Milles, 4th Baron Sondes (1794-1874), stated that such an action was not, in essence, gentlemanly. Forbes walked out, possibly telling Lord Sondes what he could do with his job! What happened next is unclear but in the course of that afternoon a compromise was reached whereby Forbes would make amendments to the Continental Agreement Bill in favour of LCDR, as it went through the parliamentary process. He also had his salary increased to £1,500 a year!

Continental Agreement between the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company and South Eastern Company as ratified in 1865

The final Continental Agreement was ratified on 10 August 1865 and started with LCDR receiving 32% and SER = 68% progressively closing until 1872, when both companies would receive 50-50%. Payments were made every half-year and came into operation immediately. SER were not happy over the final agreement and a court battle ensued, which Forbes won on behalf of LCDR.

Although LCDR had been awarded the contract for carrying mails, Churchward refused to accept the decision, stating that in the final year of holding the contract his ships carried 131,030 passengers and that they would remain loyal to his company. In Calais, on the morning of LCDR’s first day, Captain Jenkins of Churchward’s ship, Vivid II and Churchward’s solicitor shephered passengers onto the Vivid II, demanding that the mails be put aboard too. The ship was steamed up and was ready to go when the French Vice-Consul arrived and insisted that the mails were loaded on to the LCDR ship Samphire. The Samphire left France with the mails and the passengers. Sortly after Vivid II also set sail for Dover but without either mail or passengers. That evening Churchward waited on Admiralty Pier to meet the mail train from London with Vivid II standing by. The mails, however, were loaded straight onto the Samphire and, as in the morning, after she left Dover the Vivid II followed her but again with neither mail or passengers!

This situation carried on for a short time but Churchward recognising that passengers were not loyal to him as the LCDR trains from London always tied in their arrival with the departure of the LCDR packet to Calais, Churchward capitulated. Arrangements were made through Forbes for Churchward to transfer his steamboats, offices and packet yard to LCDR for £120,000. This Churchward agreed. LCDR would pay instalments of £7,000 a year until 1870, made up of cash, preference shares and bonds bearing 5% annual interest. LCDR also agreed to pay Churchward annuities of £800 per annum to 1870 for his share of the Dover-Ostend Belgium contract. Churchward held this contract jointly with a shipping subsidiary of Belgium state railways, Belgium Marine. Before the deal was signed with LCDR, Belgium Marine applied to the Belgium government to buy out Churchward’s share and offered the Belgium government 100,000frances for the full contract. They were successful and from then on Belgium Marine held the monopoly of the Ostend-Belgium route for over a century.

Forbes, and probably the LCDR Board members, were annoyed at Churchward’s double dealing and this raised concern over the French Calais-Dover contract that was also part of the deal with Churchward. The contract had been negotiated in 1860 and was due to expire in 1870. LCDR could not buy the contract from Churchward as the French insisted that the main owner was a French national or company. Churchward had got round this with a sleeping partner M. Clebetteal & Co of Dieppe. It was therefore agreed that LCDR would run the service and receive 70% of the total receipts earned each year.

With the loss of the loss of the Belgium contract, Forbes had envisaged running a passage service – passenger and goods carrying but no official mail – from Dover to Boulogne. The Northern Railway of France opposed this, as they felt that it would conflict and cause confusion in people’s minds with the SER Folkestone-Boulogne packet service. Forbes therefore decided to concentrate on the Dover – Calais packet services and purchased Churchward’s steam packets to augment LCDR’s. These were:

Vivid II formerly the Onyx, an iron paddle steamer built in 1846 by Ditchburn and Mare, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and 294 gross tonnage.

L’Alliance formerly the Garland, a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich and 295 gross tonnage. Her name was changed to L’Alliance to comply with French demands when, in 1855, Churchward first secured the contract to carry French mails from Calais to England.

Prince Frederick William of Prussia – usually shortened to Prince Frederick William, the 215-ton gross iron paddle steamer was launched in 1857, and designed by James Ash. She was 180-feet in length and 20-feet beam, 203-tons gross with 2x75horse-power engines.

Included in the deal because Churchward had no use for her, was the 149-ton gross iron paddle steamer Jupiter, which he had bought in 1856 as a relief ship. She had been built and worked as a Thames pleasure steamer and had not been fitted out for the packet industry.

On the securing of the packet fleet and the packet yard Martley took responsibility of the latter. He then, along with Forbes and the packet boat captains, settled down to get his head around the General Post Office rules that governed packet ships. When Churchward had won the contract back in 1854, the rules governing the Packet contract were basic. The appointed companies had to carry the mails to and from the stated Continental or Irish ports fast and regularly. Over time the remit was tightened and by the time LCDR won the Dover – Calais contract, the book was thick with clauses including the demand that the packet companies had to employ the very best ships and equipment to standards set by the Admiralty, who undertook regular inspections.

Once up and running, LCDR ran an efficient service that complied, as far they were aware, to the rules and regulations governing packet boats. Further, the LCDR packet ships, Samphire and the Maid of Kent quickly became firm favourites with the British Royal family and their relations. They were always given a special service and a warm welcome with as many dignitaries as possible in attendance. Typically, on 5 October 1863, the newly elected George I, King of the Greeks (1863-1913), brother of Alexandra of Denmark, the Princess of Wales (1844-1925), arrived in Dover at 15.00hrs having crossed from Calais in the Samphire, the journey having taken 1hour 26minutes. On disembarking, the King and his entourage was welcomed by local dignitaries and military personnel as well as LCDR senior management. The Royal party then lunched at the Lord Warden Hotel before leaving for London Victoria on a special train under the superintendence of Henry Cox (born 1828), the Harbour Station master.

Pilots Tower opened in 1848. The ground floor was gutted in 1864 to enable the London, Chatham & Dover railway company line to go through the tower from Harbour railway station on to Admiralty Pier. Dover Library

With regards to the provision of special services to members of the Royal family, the packet contract helped in that it automatically gave LCDR the prime Berth 2 on the Admiralty Pier. On winning the contract, LCDR had immediately petitioned DHB to lay a connecting line from Harbour Station. This was agreed but between the Station and the Pier stood the tall, highly ornate and very solid Pilots’ station. Opened in 1848 besides its practical purpose, it was also of interest to tourists, so could not be demolished. Albeit, as Forbes was aware, LCDR’s finances were stretched and the Board were also reluctant to spend any more money than necessary on the Packet service.

Forbes approached the mechanical and civil engineer, Thomas Russell Crampton (1816-1888), and his plan was implemented. The ground floor of the tower, with a ceiling height of 20ft (over 6 metres), was gutted and the LCDR line was laid through the Tower! This had the unexpected effect of turning the visitor interest into a lucrative tourist attraction for the town! From the Pilots tower the railway line ran onto the Pier, on the harbour side of the SER line, to Berth 2 and was opened on 30 August 1864.

This was the first day that LCDR ran trains onto Admiralty Pier and coincidentally, Francis, Duke of Teck (1837-1900) and his wife Princess Mary of Cambridge (1833-1907), arrived and were given the Royal welcome. They had travelled from Victoria Station, London on the 20.30hours LCDR train to embarked on the LCDR packet Wave for France. Forbes, used the event for publicity purposes, saying that the visit was to open the LCDR Admiralty Pier line! The Wave was a 344-gross ton, 199 foot long iron paddle steamer built by Money, Wigram & Co, Blackwall, Middlesex in September 1863. Like the other LCDR ships, she had 2×80 horse power diagonal oscillating engines by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co. Her sister ship Breeze, with a gross tonnage of 349, was similar in all respects except that she was slightly wider that the Wave.

LCDR were not only impressing Royalty, they had caught the imagination of Dover’s business community. In December 1863, Baron Sondes was invited to lay the the foundation stone of the Clarence Hotel, Dover. This was on the corner of Townwall Street and Woolcomber Street, built by the Clarence Hotel Company whose directors included Steriker Finnis and Rowland Rees senior, both major shareholders in LCDR and part of Dover Harbour Board. The hotel was designed by John Wichcord (1790-1860). It opened in 1865 but was eventually demolished and the Burlington Hotel was built on the site.

In February 1864, LCDR reported that the accounts for the final six months of 1863 showed that £3,984,947 had been spent on main line services, £4,586,883 on the Metropolitan Extension in London and £23,713 on shipping from Dover. The number of passengers carried by LCDR on their ships was 123,053, a fall since the year before. This, Forbes told the Board, was due to the Great Exhibition, held at Crystal Palace, which had artificially swollen the number of passengers coming from the Continent. According to Churchward’s figures, he said, in 1860 there were only 76,318 passengers. From the main line services £171,086 had been received, from the Metropolitan Extension £30,928 while from Dover shipping the net receipts were £34,516. Lord Sondes and the other Board members thanked Forbes and congratulated themselves but resolved that the company would not be paying dividends.

When Sondes explained the reasons why at the shareholders meeting, a Mr Shaw from Dover responded by saying that in his opinion, the Board directors were in no position to congratulate themselves. ‘The company had started out with £700,000 capital from shares and borrowing,’ he said, ‘but this now stood £9,000,000! In his opinion shareholders should employ counsel in Parliament to protect their interests.’ Shaw went on to say that the Dover shipping operation was the only part of the company that was profitable. ‘Yet’, he said, ‘Dover was being badly treated by LCDR.’

LCDR Company Secretary, George Augustus Frederick Charles Holroyd 2nd Earl of Sheffield (1802-1876), told the shareholders that the Board of LCDR had agreed with the full backing of shareholders that the company’s operations in Dover was to create a world class cargo terminal. Adding that ‘until the connection between Admiralty Pier and the Metropolitan Extension was completed, there was little point in spending or doing anymore than necessary at the Dover end.’ To Forbes surprise, Rowland Rees agreed with Holroyd, saying that ‘once the Extension was completed, an enormous amount of traffic would come through Dover and it would be then time to expand the Dover terminus.’

Forbes was to remember Rees reasoning over the necessity for adequate infrastructure before undertaking the prime objective, in this case Dover becoming a major cargo terminal. This, with a combination of other reasons, cemented Forbes’ belief that the cross- Channel packet operation was a better option than a cargo terminal. The Company had four packet ships, the Samphire, Maid of Kent, Breeze and Wave operating twice daily crossings of the Channel, with the other ships in the fleet in reserve. The boat trains left Victoria railway station, London, at 07.00hours and 15.00hours. Passengers on the earlier train arrived in Paris at 18.00hrs and on the afternoon train, arrived in the French capital at 07.20hrs the following morning. Forbes’ advert assured passengers that the tickets provided a through service and there was no landing by small boats as at other ports – obliquely making a jibe at SER’s Folkestone-Boulogne service!

Although the adverts did make potential passengers aware of the Dover-Calais service, one of his major problems was the port of Calais. There the embarkation and disembarkation of passengers left a lot to be desired, particularly at night. On 26 December 1863 George Roland and his wife, from Edinburgh, were returning to England via Calais and were the first of a stream of passengers in France to go on board the ship that was to take them to Dover. It was very cold but both were well wrapped up and wearing the appropriate footwear to negotiate the stairs, wet quay etc. As directed by the conductor, they went down the unlit stairs to the dark quay. Then they had to negotiate a gangplank, without railings, to board the ship. Mr Roland lost his footing and fell into the sea. His wife would have fallen in too had not the passenger behind her grabbed her. Mr Roland was fished out by crew members of the ship and other passengers, but soaked through boarded the ship. On returning to the UK Mr Roland complained to Lord Sheffield, the LCDR Company secretary, to be told that the responsibility for boarding, sailing and leaving the ship was that of the passenger and LCDR disclaimed all liability.

The response was publicised by Mr Roland and Forbes brought the matter up with the LCDR Board. He was told that this only applied to ordinary passengers. People with status were ensured a full, safe and positive reception. For instance when Archduke Maximilian of Austria (1832-1867), his wife and their entourage, were travelling in supposed incognito on a special train arriving at Calais at 01.00hours in March 1864. For them, the whole harbour was lit up and staff were there to ensure that they embarked on the packet ship, Breeze, safely! This was not lost on the passengers at the quay that night, who had been marshalled via a dark and hazardous route and of this, Forbes was aware.

Internationally, this was the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and in January 1864, Forbes sold the L’Alliance to the Confederate States of American for blockade running along with Jupiter. However, while crossing the Bay of Biscay the Jupiter foundered and was lost. To replace these, he ordered the 327.29gross tonnage Prince Imperial iron paddle steamer from James Ash & Co of Poplar. She had, 2×90 horse power oscillating engines that were supplied by Penn’s of Greenwich. The vessel arrived in September 1864 for the night service. To raise finance for this outlay, the previous autumn he had briefly chartered, the Scud, to Belgium Marine. On arrival of the Prince Imperial, Forbes sold Foam and Petrel to a Mr F Sabel of Liverpool for the China trade.

The LCDR half yearly report ending on 31 December 1864, stated that the receipts on the 72½ miles of main line track continued to increase amounting to £182,240. However, the expenditure on the main line between Bickley and Dover was £4,443,602 while the receipts from cross Channel traffic was only £32,352 out of which were expenses that amounted to £19,156 and included the cost of two new ships. Shareholders were angry but the LCDR Board assured them that once the cargo terminal opened at Dover, the situation would improve.

The second ship that Forbes had ordered came from James Ash & Co of Poplar, and was the 388 gross ton iron paddle steamer La France. She arrived in Dover on 4 January 1865 and Forbes publicity hailed her as the fastest steam ship to make the crossing. This came under attack from John and William Dudgeon of Cubitt Town, London, the builders of the Mary Augusta, a 970ton 280 horse power twin screw steamship built for the American Civil War as a blockade runner.

The Mary Augusta made her trial run between Dover and Calais and this was turned into a race against La France in March that year. The wind was a moderate East North East and starting off the end of the Admiralty Pier at approximately 09.30hours by 09.53hours both ships were off the South Foreland and level pegging. Then a hot bearing problem developed in the starboard engine of the Mary Augusta that resulted in a reduction of revolutions. Nonetheless, she succeeded in drawing away from La France and by 10.45hrs, the heated bearing having cooled, the Mary Augusta made faster headway than her rival. At 11.04.45sec, the Mary Augusta reached Calais head, turned round and headed back to England. With the help of her fore and aft sails she arrived back at Admiralty Pier before La France. Her total timing was 2hours 45minutes and 10 seconds and the Dudgen brothers were pleased with the success. James Dunwoody Bulloch (1823-1901), the Chief Agent in England for Confederate Army, purchased the Mary Augusta but the war was over by the time she arrived.

The outcome of the race was a blow for Forbes and the Board was unhappy as the race was given a lot of publicity and the Company shareholders were becoming increasingly disgruntled. At one meeting Rowland Rees asked Forbes to explain, given the persistent fall in the number of passengers travelling on LCDR ships, why more ships were being brought into service. Rees told the packed meeting that the fall in the number of passengers between 1862 and 1863 was 6% while and in 1864 there had only been 120,251 passengers giving a fall of just over 2%. Forbes responded by saying that LCDR had taken over a number of old ships from Churchward, who was at the meeting, when they first began operations. These, he said, had been sold off and were being replaced by the new ones to attract more passengers. Churchward, is not recorded as making any comment.

At a subsequent Board meeting the cross Channel passenger statistics and the lack of greater income from the service was discussed. Regarding the latter, Forbes told the directors that SER were not playing fair over the Continental Agreement. SER had built the new Shorncliffe railway station (now Folkestone West), and were claiming that passengers alighting there were NOT going to the port of Folkestone and therefore their ticket receipts were not included in the Agreement. In reality, he said, the passengers were invited to alight and watch the engines being changed before the train went on to Cheriton Arch station that served the port of Folkestone. Forbes went on to say that although the Continental Agreement for 1864 netted £368,000 between the two companies because of the division LCDR only received £125,120. At the time the Continental Bill had not been finally ratified by parliament and Forbes used the opportunity to make further changes but the LCDR Board of directors did not agree. The Continental Agreement was finally ratified on 10 August 1865 and at the time LCDR were running into major financial troubles. These are discussed in detail in London, Chatham and Dover Railway – Part I story.

About the same time as the Continental Agreement was ratified another LCDR shareholders meeting was taking place with LCDR’s growing financial problem being the main issue. LCDR’s Chairman, Lord Sondes, successfully motioned the authorisation to convert ordinary shares into ordinary capital stock in the general undertaking of the Company. On the basis of this 2,400 appertaining to the Dover – Calais packet service were converted to interest bearing shares of £25 each and named Dover preference arrears stock. They were redeemable and raised £60,000. Sondes then proposed that ‘The Directors were also authorised to capitalise further arrears of interest on Dover preference capital by the creation and issue of £110,000 addition shares or stock, redeemable and entitled to a dividend not exceeding 5% per annum.’ This Forbes knew was not for the packet arm of the Company but to meet costs of the Company’s London Metropolitan Extension. A number of shareholders also recognised what was happening but Lord Sheffield motioned for their views to be over-ruled and this was carried.

On the night of Thursday 26 October 1865 one of the heaviest gales up to that time occurred. The two LCDR ships transporting mail that night were the Breeze under the command of Captain Matthews and the Prince Frederick William under Captain William Clark. So rough was the weather that the vessels left Admiralty Pier over 2hours late at 00.35hours and 00.37hours respectively. The Breeze had 131 Continental mail boxes and 75 passengers and Prince Frederick William had 210 boxes bound for India, China and Australia. Battling against the roughest seas that Captain Matthews had ever encountered he brought the Breeze safely into Calais at about 02.30hours. The Prince Frederick William did not arrive and as the night wore on there was increasing concern. At about 04.00hours another steamer was sent out from Dover to look for her and just after 06.00hours the Prince Frederick William arrived in Calais aided by the ship sent to find her. The strain of ploughing through the violent waves had broken the intermediate shaft of one of her engines disabling one of her paddles.

The Samphire Accident

At 23.30hours on the night of Wednesday 13 December 1865, the LCDR packet ship Samphire, under Captain John Whitmore Bennett (1828-1907), was carrying mails and 78 passengers from Dover to Calais. The Samphire, had left Dover at 22.58hours, the weather was hazy, the wind North North West to North with a fair wind and ebb tide. When she was less than 5 miles out she was hit by the 500ton Fanny Buck from Boston, Massachusetts, under the command of Captain Hoad. The Fanny Buck was bound from Rotterdam – then Flanders and now the Netherlands – to Cardiff. She was laden with ballast. The Samphire‘s speed at the time of the accident was 12 miles-an-hour and 5 of her passengers lost their lives. The accident is particularly memorable as the outcome emphasised the first major legislative ground rules for ships traversing the English Channel.

The inquest was held on 15 December in Dover Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu, under the direction of William Henry Payn (1803-1887) the town coroner. LCDR’s solicitor was Wollaston Knocker (1838-1907) of Dover and those who lost their lives were, Monsieur Laynelet – traveller in the house of Messrs Bockering, Fieresand Co Paris; Miss Baines, Miss Koenig, Monsieur Duclercq and an unknown man lost overboard at the time of the collision.

The crew of the Samphire under Captain Bennett that night were, William Richards – mate, Charles Datlin – acting mate, J Fleet – carpenter and seamen: W Norris, Robert Malpas, Thomas George Northover, J Gillman, Frederick Waters and Henry George Boyce. Other crew members were Henry Hills – boy, Henry Hickings (1834-1891) – steward, Thomas Hardy – chief engineer, William Waters (b 1831) – second engineer and stokers: R Bishop, T & M Trevett and W Jones. The mail master was George Henry Suters (1836-1901). Only members of the crew of the Samphire gave evidence at the inquest. The jury’s conclusion was, in effect, that nobody was to blame and nothing was at fault, other than the Fanny Buck did not show sufficient light. They added that it was ‘the coolness and the intrepidity displayed by Captain Bennett and the crew of the Samphire in their trying position, which under God’s providence, were the means of rescuing so many lives.’

This quickly brought a rebuke from the crew and owners of the Fanny Buck as well as from ship owners and yachtsmen who frequently traversed the Strait of Dover. The letters were published in the national press with many stating that the Fanny Buck was travelling along the Channel while the Samphire was crossing it and therefore the blame rested fully on the Samphire. All the local officials involved including the coastguard described the night as moonless with a distinct haze that made it difficult to see anything that was not lit. However, the passengers from the Samphire told the media that it was clear moonlit night and that the lights from the lighthouses on South Foreland and the Cap Griz Nez, France, could easily be seen. Pilot Samuel Dane (1813-1875) said that the weather was that all cross Channel captains feared most. ‘In misty or foggy weather’ he said, ‘you can see clearly, one minute, then you are running in thick fog which suddenly lifts again, showing shipping all around and equally quickly descend again.’

The former Dover Court jury box in the former Town Hall now the Maison Dieu, where the Samphire Inquest and Board of Trade Inquiry were held.

The accident sparked such interest that journalists from national newspapers joined local reporters in attending the Board of Trade Inquiry, which opened on 21 December 1865 in the then Dover Court room part of the then Town Hall complex now the Maison Dieu. Carrying out the investigation in pursuant of the Merchant Shipping Act of 1854 and the Merchant Shipping Amendment Act of 1862 was Dover Mayor, William Rigden Mummery (1819-1868) and local magistrate, Dr Edward Farrant Astley (1812-1907). At that time the Board of Trade was the governing body responsible for all civil maritime matters including safety and the loss of British ships. The attending assessors on behalf of the Board of Trade were Captain Henry Harris and Captain Robert B Baker and the Trade’s solicitor was James O’Dowd (1809-1903). Solicitors Messrs Edwards & Son represented Mr Bowden – agent for the owners of the Fanny Buck, Mr Fox represented Captain Bennett, and Wollaston Knocker (1825-1890) represented LCDR packet service. The hearing lasted 11 days.

The Captain and members of the Samphire crew were the first to give evidence and in essence, they generally agreed that the Samphire left Admiralty Pier at 22.57hours on the evening of 13 December. The Captain had constantly used night glasses (binoculars) to aid his vision and was on the Bridge as lookout on the port side when the accident happened. With him was the call-boy Henry Hills who passed on messages, through the communication pipe that went to the engine room. Robert Malpas was lookout on the starboard side and Thomas Northover was on the bow as the forward look out. They had been told by the first mate, William Richards, to be especially vigilant as there were herring boats about. It was difficult to see dark or unlit objects because of the intermittent poor visibility. The Samphire’s navigation lights shone brightly, there was a white one on the masthead, a red one on the port bow and green one on the starboard bow. The speed was 12knots and Charles Datlin with George Boyce were on the wheel and steering South East half East.

About 15-20minutes after leaving the Pier, Northover called out that there was ‘a sail off the port bow.’ At the same time Malpas called out that there was ‘a light two points on the port bow.’ The Captain confirmed both sightings and shouted to the wheel ‘Hard To Port’, Datlin replied Port and the Samphire responded. Seconds later, as the Fanny Buck loomed and the Captain rapidly ordered to the engine room, ‘Case Her, Stop Her.’ The orders were immediately carried out. The barque struck the Samphire on the port bow and the Captain ordered the engine room to go astern. The Fanny Buck’s bow was on the deck of the Samphire and two Fanny Buck crewmen fell from her bow onto the Samphire. They both were wearing caps, a gansey – a seaman’s knitted woollen sweater – and trousers but no shoes or stockings. At this point, for the first time, the crew members of the Samphire observed a dim green light on the starboard side of the Fanny Buck.

On board the Fanny Buck was pilot, John D Hondlehone from Rotterdam, who was navigating at the time of the accident as the captain was ill and indisposed. The mate was Daniel Pigsaud, who acted for the captain. The total crew consisted of 3 Englishmen, 2 Americans, 1 Swede, 1 Prussian – Frederick Drenkow – and 5 others. All could speak English but at the hearing, to ensure clarity of understanding, Samuel Metcalf Latham (1799-1886) as the Dover Dutch consul, stood by as interpreter. Although a steamer, the Fanny Buck was under sail at the time, with all the plain sails set up to the top gallants. The wind was North to North North West and they were steering west by north alternating with west by south, depending on which tack they were on. They were travelling at about 6-7knots an hour and at the time of the accident, the Fanny Buck was close hauled to the wind on the starboard tack.

All the Fanny Buck crew agreed that the weather was at times hazy then becoming foggy and occasionally clearing. They also agreed on all of the events on the Fanny Buck that night. Frederick Drenkow was the lookout on the foredeck and James Sheppard was on the wheel. Two others were on general look out while the pilot, Hondlehone, and the mate, Pigsaud, were on the aftdeck. It was also generally agreed that the Fanny Buck’s navigation lights complied with the British Admiralty ruling of a white one on the masthead, the red on the port bow and green on the starboard bow. They all shone brightly and the mate, Pigsaud, had started checking and trimming them immediately after the four bells had been struck – at 22.00hours. This procedure took about three to four minutes each light.

About 15 minutes before the collision, Drenkow had called out in Dutch that there was a white masthead light in-shore of the Fanny Buck, and Hondlehone gauged that the light came from what turned out to be the Samphire. She was about 2-3 miles away and four points on the starboard bow. Hondlehone did not order Sheppard to alter course as he said that it was the duty of the Samphire to get out of the way. Albeit, about 8-10 minutes later Drenkow called out that there was a red light and then seeing both a red and green light called out ‘Steamer ahoy, Back engines’.

Hondlehone ordered Drenkow and one other man to loudly hail the Samphire from the foredeck. This they did but the Samphire carried on. On impact both men fell onto the Samphire’s foredeck. The shock of the impact on the starboard bow forced the Fanny Buck to heel over to port but she straightened up when the Samphire pulled back. A whistle was heard from Samphire and there was shouts for help but the Fanny Buck continued on her course. Her stanchion on the starboard bow was badly damaged causing her to take in water, this Hondlehone said, would have increased if the Fanny Buck had changed to a port tack. All hands on the ship were then involved in taking the sails down and using them to make emergency repairs to stop the flooding before the Fanny Buck sank. The Fanny Buck then headed for Sandgate, along the coast, where she was anchored. After nailing canvas over the hole she was brought back to Dover.

The last witness from the Fanny Buck was the steward, James Miller. In his affidavit he had said that part of his duties was looking after the navigation lamps. He concurred with the rest of the crew that the mate, Pigsaud, had checked and trimmed the lights immediately after the four bells had been struck. At the time of the accident Miller said, he went on deck and all three lights were burning brightly. However, under questioning on his routine that day, Miller said that earlier in the day he had taken the three lamps to his cabin, to clean and prepare them for that night. At the time he was also looking after the Fanny Buck’s, captain who was very sick. He had trimmed one of the lamps when the captain summoned Miller with his bell. On returning to his cabin Miller poured a gill of oil into each lamp adding that it was of poor quality and tended to smoke when lit.

When the collision took place Miller was in bed and was thrown out due to the impact. As he left the cabin the mate, Pigsaud came to him with the green lamp in his hand and said ‘Steward, this lamp is out.’ Checking it, Miller found that two of the three tubes did not have wicks so he inserted two new ones. He then filled the lamp with oil at which point the captain’s lady called for Miller to attend her husband. When Miller returned to his cabin, the lamp was gone. The following morning, Miller found the lamp on deck, leaning against a locker, together with the other two lamps. When it was pointed out that this differed from his affidavit, Miller replied that when he heard of the deaths caused by the accident, he felt remorse as, in his mind, it was the Fanny Buck’s inadequate navigation lights that had caused the accident.

Events on the Samphire

From the affidavits and evidence given in the coroner’s court by the Captain and the crew of the Samphire, it was clear that following the impact Captain Bennett ordered the boats to be lowered and the rockets to be fired. However, the rockets and the blue warning lights that when displayed indicated that the ship was not underway, were in the fore compartment. This was under water so even if they could have been retrieved would not have been of any use. Also under water was the fore cabin in which three passengers had drowned. Two were Mieta Baines, aged about 20, and daughter of Reverend Edward Baines (1801-1881) of Yalding, Kent and her German governess Georgina Koenig about 23 years old.

The Samphire had four boats each with four oars, 2 cutters and 2 lifeboats. Before any of the boats were lowered three passengers with their luggage had already climbed into the first cutter. The passengers remained seated with their luggage close to them and when asked, refused to move and this limited the number of people the cutter had room to carry. It also hindered the lowering of the cutter but on hitting the sea, on the orders of Captain Bennett, William Richards together with four crew members and with the three passengers still on board, rowed to Dover for help. The Belgium mail packet, Belgique had passed Samphire, but as no blue lights were showing carried on to Dover. She was being tied up at Admiralty Pier when the cutter arrived. On hearing of the calamity, the Belgique’s captain immediately ordered the ship to go to the aid of the Samphire.

The second cutter, with a great deal of difficulty due to about 20 passengers with their luggage having already commandeered the boat and a passenger who had a knife with which he was trying to cut one of the lines. When he saw Captain Bennett he put the knife away, sat down and the boat was successfully lowered. On board were Malpas, two other members of Samphire’s crew and Drenkow from the Fanny Buck. However, due to the tight squeeze and particularly the passengers luggage, a bung was displaced and lost. In consequence the boat started to take in water but unaware of this, Captain Bennett ordered Malpas to go to the Fanny Buck and ask them to ‘heave to and help’. They rowed after the Fanny Buck and all the seamen, including Drenkow called out but no notice was taken. As the Fanny Buck increasingly moved away from the boat, Malpas at the behest of the demanding passengers, along with the other three seamen, rowed to Dover.

It was not long after that it was realised that the boat was leaking and that this was due to the missing bung. Malpas told the passengers what he believed had happened and told the passengers to throw their luggage overboard if they wanted to reach Dover. The passengers refused nor would they help find the missing bung. Without any instructions from Malpas, all four seamen started stripping off and used their clothes to try and plug the bung hole. Not one passenger parted with any of their clothing or possessions. As water was still seeping in, Drenkow, who had been loaned a pair of boots by another Samphire crew member, used them to bail the water out, while the other three rowed the boat. At the Inquiry, passengers on board the boat that night all concurred that it was not their job to row the boat nor had mere seamen the right to tell them to throw their luggage overboard. The four crew men did say that one of the passengers did help with the rowing and another helped Drenkow in bailing out.

The cutter arrived at Admiralty Pier at 01.45hours with the passengers being taken to the nearby Lord Warden Hotel where the kitchen staff were just arriving. The marine superintendent, Sir Luke Smithett (1800-1871), had already arrived on the scene and had ordered the kitchens to be opened. He and his staff then offered the distraught passengers the option of either returning to London on the 04.00hours train or to rest at the hotel and take the next packet to Calais at 09.30hours that morning. Those who had lost their tickets were given passes. Albeit, later a number wrote strongly worded letters to the press and stated under oath at the Board of Trade Inquiry, that this was untrue. They had been abandoned by the four crew men at the deserted Hotel and were unable to even get a hot drink. At the inquiry, other passengers from the cutter refuted this and concurred with Smithett’s account. The four crew men were taken to the Sailors’ Home and all stated that they were well looked after.

As the first of the lifeboats was being prepared Captain Bennett insisted that the few ladies on board were to be helped to get into it. However, a number of men bulldozing their way through with their luggage, pushed past them, sat down and refused to get out. They also all sat in the aft section, having stowed their luggage in the bow. Frederick Waters who was responsible for lowering the lifeboat at the bow, was unable to get near the Clifford equipment and the Captain asked them to remove some of the cases so that Waters could get in. This they did but when Northover, who was in overall charge, gave the order to start lowering the boat a couple of the passengers, complained that crewman Norris, who was responsible for the aft equipment, was elbowing them. They stood up and started to clamber down the boat pushing Northover aside. The boat tilted then dropped, still at an angle, and all the passengers, their luggage and the crew fell out.

The lifeboat, upturned but with the help of the crew on board, most of the passengers used it to gain a hold of the boat-tackle and climb back onto the Samphire. It then became apparent that one passenger was still in the water and lifebuoys were thrown to him. Captain Bennett, with a running bowline round his body, dived in and secured a line around the man – M. Duclercq a merchant from Gravelines, now France then Flanders. Duclercq, like all of the other passengers, was wearing a thick heavy coat and winter boots. These quickly filled with water and as Duclercq was being raised, the weight of his boots pulled him out of the harness and he fell into the sea and drowned. Another man was then seen and Captain Bennett again went to his rescue but before reaching the man, believed to be a Russian nobleman, sank without trace.

By this time the second lifeboat was ready to be launched and regardless that Captain Bennett had ordered that the ladies were to be given priority, about 16 men with their luggage sat in it and refused to move. However, Suters did manage to get on the boat, but the passengers made it clear that there was no room for the mail sacks, so these were left on Samphire. Members of the crew lowered the lifeboat safely and she started for Dover. As the lifeboat was going around the stern, the Samphire‘s steward, Hickings, who was on the ship, spotted Boyce in the sea. Boyce was holding up a man with a lifebuoy around him. Hickings’ yelled to Charles Datlin the acting mate who was in charge of the lifeboat, to go to Boyce’s aid. A fracas broke out, then eventually the lifeboat rowed off in the direction of Dover. In the meantime, Hickings’ with the help of stoker Bishop hauled out Boyce and the man, who was still alive, to safety.

The remaining passengers, including all the ladies, Captain Bennett, Henry Hickings, the two engineers – Thomas Hardy and William Waters – along with Boyce and Bishop remained on the Samphire. Due to the separate water tight compartments, the Samphire did not sink and although her engines still functioned, she had lost her steering power. The Belgium mail packet Belgique, arrived 40 minutes after being told that the Samphire was in trouble and took the remaining passengers and their luggage to Dover. They left a stock of blue lights in order to warn other craft that the Samphire was disabled. About two hours later the Belgique returned by which time the Samphire had drifted some 10 to 12 miles and into thick fog. Eventually the Belgique located the Samphire and the distressed ship’s engines were fired up so that the Belgique could tow her. Both ships arrived in Dover harbour at about 08.15hours on 14 December.

The Questioning of Captain Bennett

Each member of both crews was questioned at the hearing of the events that night and from Samphire, Captain Bennett came in for the most scrutiny. The three representatives from the Board of Trade, Captains Harris and Baker and solicitor O’Dowd focussed their attention on the ship’s boats, while Dover’s Mayor Mummery and Dr Astley closely questioned Bennett on aspects of the packet contract.

In answer to the Board of Trade representatives questioning, Bennett told the hearing that two of Samphire’s boats were lifeboats fitted with the Charles Clifford’s method of lowering ships’ boats and each with four oars and were always left uncovered during winter months in case of emergencies. The other two boats were four oared cutters. The Captains then asked how the cutter was launched in which the bung was missing. Bennett re-iterated that it was the second boat to be launched and that the passengers had already boarded it stowed their luggage under the seating before it was prepared and were badly seated. The passengers were all well wrapped up against the winter weather and were loudly demanding that the boat should be launched forthwith. This was regardless that there were no crew members on the boat but they were so sure that the Samphire was sinking fast that one of the passengers, who had a knife, was standing up and trying to cut through the lines that were holding the boat to the Samphire.

Asked how Bennett believed the passengers should have been seated on the boats, he replied that they should have sat in the thwarts – across the boat – with equal number on either side and remained seated. Asked if this applied to the lifeboats and Bennett replied in the affirmative. He was then asked if, at any time, the passengers were told where to sit, to remain seated and not to take their luggage with them. Bennett replied that he had asked them and added that he was a mere captain while the passengers were gentlemen. One did not tell ones social superiors what to do. Solicitor O’Dowd asked Bennett why he had not ordered his crewmen to unload the boats of the passengers luggage or at least persuade the passengers to leave their luggage behind. ‘That night the passengers,’ replied Bennett, ‘were not open to persuasion to do anything against their will.’

They then asked Bennett about the Clifford equipment and what, in his opinion, had gone wrong on the first lifeboat. Bennett said that once he managed to get Frederick Waters into the bow, there were three members of the crew involved in lowering the lifeboat using the equipment. Northover was at the centre, in charge of the boat and of lowering the line and aft was Norris. When all were seated, Northover started lowering the boat by putting the line one turn round the cleat and then slowly slackening it off. It was at this point that the two passengers clambered past him and Northover let go of the line. The lifeboat tipped aft and, as the hearing knew, every one and everything fell into the sea.

They then asked about Suter’s role in the events that night. Bennett, possibly surprised by the question, said that Suter’s responsibility was the mail. This he carried to be loaded onto the last boat to leave the ship but there was no room. Suter, boarded the lifeboat but Bennett was not sure if he had helped to row it. The mail was taken to Dover on the Belgique and loaded on to the next packet to leave Dover for Calais. On being asked what he knew of Suter’s background Bennett said that he hardly knew Suter.

The two Captains were none committal as to what they thought of Bennett’s evidence but did say that in their opinion, Bennett had acted courageously in trying to save M. Duclercq life. That although he was wet through and that it was very cold, he had remained on deck so that the second lifeboat was lowered safely.

In response to Mayor Mummery and Dr Astley’s questioning over the packet contract and requirements appertaining to the duration of the crossings. Bennett said that to comply with the contract the duration of the voyage was not to exceed two hours and five minutes. If the crossing was quicker then LCDR was paid a bonus of £5 by the Postmaster General. Out of this the ships’ captains received 2shillings and members of the crew the same amount shared between them. If the duration of the crossing exceeded the time limit by 15minutes or more, LCDR was fined at least £5 by the Post-Master General depending on the duration and causes of the delay. A proportion of the captains and crews packet money was deducted accordingly. LCDR paid the captains and the crews their packet money every quarter, while they received their wages after every set of crossings.

Conclusion of the Samphire accident

Shipwright George Barber was the Board of Trade surveyor and he told the hearing that he examined the lights of the Fanny Buck in the Harbour Master’s, Richard Iron, office. He said that the lamps were smaller than those of the Samphire, with a short range but were in good condition. Each contained one burner with three cottons and held about half a pint of oil. He had spoken to Miller and asked the steward if the lamps were as he had prepared them on the fateful day. Miller, at the time, was unaware that this was contentious and examined the lamps. He said that two of the three wicks in the red lamp were those he had inserted but the green wicks were totally different and of a better quality. Barber, told the Inquiry, that in his opinion, the replacement wicks would have made a difference to the brightness of the lights but that he would have expected them to be trimmed about every four hours.

On examining the places where the lights had been fixed on the Fanny Buck, Barber surmised that the lights would have been difficult to see especially because of the poor quality of the wicks and that such low quality would not have been allowed on a British vessel. Barber also stated that he had examined the three remaining Samphire boats and that the Charles Clifford’s launching gear on the one lifeboat remaining, with that fitted, lacked adequate maintenance. The rowlocks were out of true and the oars and rudders of all three boats needed attention. He also examined boats in service on another of LCDR ships and found that they too lacked adequate maintenance.

In Dover, the overwhelming opinion was that Captain Bennett was heroic for not only had he managed to get most of the passengers safely off the Samphire, but ensured that they reached the harbour safely. He had made valiant efforts to save the lives of those that fell into the sea and he had stayed on the half submerged vessel in order to bring her home. It therefore came as shock when the Board of Trade stated that Captain Bennett of the Samphire was at fault for causing the accident.

Their report stated that Captain Bennett was driving his vessel too fast for the adverse weather conditions. This, they recognised was due to the demands of the General Post Office’s Packet Contract and therefore the damage to the ship and loss of life did not only arise from his fault. They recognised that Captain Bennett’s conduct after the collision was exemplary, using his utmost endeavours to save lives and to adopt such measures as were proper. This would have been expected from him and it was for these reasons alone, the Inquiry report stated, Captain Bennett would not have his Master’s certificate cancelled or suspended.

The conduct of the crew came in for a fierce rebuke. The report stated that those in the boats had shown a lack of concern for the plight of those still on board the Samphire, which was sinking. Charles Datlin, the acting mate, was deserving of the highest censure, they wrote, as he had effectively made off in the lifeboat. The fact that the passengers were demanding, ignored requests and difficult to control was no more than natural under the circumstances and formed no excuse for poor conduct by the Captain and crew. This the Inquiry blamed on the weakness of Captain Bennett in handling alarmed, panic stricken passengers. The clumsiness of lowering of ship’s boats received censure and this was blamed on the lack of training and maintenance. However, the Inquiry report was particularly scathing of the mail master, George Suters, saying that he had previously been a carpenter in the Royal Navy and yet he had deserted his mails and his ship in a cowardly manner by getting into one of the boats.

LCDR came in for fierce criticism over the lack of maintenance of the boats and lack of crew training. Regarding the state of the boats, Martley took responsibility and Forbes took responsibility over the lack of crew training. The report went on to say that although the Samphire was carrying a greater number of boats than was required by the Board of Trade in line with Government regulations, there was insufficient to secure the safety of ALL the passengers and crew. This, the report stated, was possibly the cause of the passengers panic. The behaviour of the crew of the Fanny Buck came in for criticism too. The lights on the Fanny Buck, the Inquiry report stated, were shown to have been inadequate and of not returning to the scene of the accident and offering help was also condemned. With these in mind, the Inquiry held them as partially culpable for what had happened. Finally, the provisions of the Government Packet Contract was seen as the main culprit for the accident as, said the Inquiry report, it held out a direct premium for quick passages in all weathers and conditions. This put a great moral pressure on the owners and commanders of the mail vessels by the general public, which was wilful and dangerous.

Following on from the Board of Trade Inquiry was the Court of the Admiralty Hearing. This was before Stephen Lushington (1782-1873) and the Trinity House Masters. The Hearing took place in February 1867 and lasted two days. All those who attended believed that the Hearing was to settle the principle conflict for compensation purposes, whether the Fanny Buck had her proper lights exhibited. However, the Masters of Trinity House reminded the Court of the legal conditions laid down in the Merchant Shipping Act of 1854 and the Merchant Shipping Amendment Act of 1862. That although the Fanny Buck was a steamer, at the time of the accident she was under sail and as such she would have difficulty altering course. The Acts made it clear that in all circumstances steam had to give way to sail. Thus the unanimous opinion was that the Samphire was to blame for the accident as the Captain and the crew could see that the Fanny Buck was under sail. The subsequent Judicial Committee of the Privy Council affirmed the Admiralty Court’s verdict and stated that the Samphire was totally to blame for the mid-Channel accident. LCDR were ordered to pay damages of £1,400 10shillings 10 pence to the owners of the Fanny Buck.

These days, power driven vessels, when under way, must carry on or in the front of the foremast or the forepart of the vessel a white light, visible over an arc of the horizon of 225 degrees shown equally to port and starboard. Additionally, vessels over 150 feet in length must carry a second white light with similar characteristics mounted towards the stern, with a significant distance between them. This white light must be mounted at least 15 feet higher than the forward light. Sailing vessels may be readily identified when under way, as they must carry two lights at the top of the foremast, the upper one red and the lower one green. They should be sufficiently separated so as to be clearly distinguished.

LCDR Packet service after the Samphire Accident

The Samphire accident was hardly discussed at the numerous LCDR meetings that were being held at the time. This was possibly because LCDR were fast approaching the rocks of bankruptcy and most of the Board members were in denial over what was happening. The imminent financial collapse was due to the Company’s prime agents running their London operations having ‘created‘ false share floatations – See London Chatham and Dover Railway Company Part I for details. Typically, although the Board of Trade had stated that ship maintenance, crew training etc. were inadequate these were not of concern to Board. The shipping operations were little more than a soft touch to raise money. In August 1865 the Chairman, Lord Sondes, successfully motioned for the authorisation to convert 2,400 Dover shipping preference interest bearing shares of £25 each. Called the Dover Preference Arrears Stock, they were redeemable and raised £60,000. At that same meeting, Sondes proposed for the directors to be authorised ‘to capitalise further arrears of interest on Dover preference capital by the creation and issue of £110,000 addition shares or stock, redeemable and entitled to a dividend not exceeding 5% per annum.’ Although a number of shareholders objected to the motion and demanded that the emphasis should be on bringing the fleet up to standard, crew training etc., the motion was carried.

Forbes LCDR advert, without time taken, for the Dover-Calais packet service and the SER advert which includes the length of time. Times 3 March 1866

In response, Forbes increased the advertising to attract more passengers emphasising the the Continental connections to the cross Channel packet service. The Dover-Calais route, the adverts told the punters, was the shortest sea passage and that the company had new and the fastest steam packets making the crossing on a daily basis. His adverts went on to say that LCDR offered passengers two choices, they could either leave Victoria station at 07.25 hours on which they had the choice of 1st and 2nd class journey or, at 08.30, for the 1st class express. They would then leave Dover for Calais at 09.35hours or 22.40hours depending on their choice. The length of time taken was not given. Following the Samphire accident Forbes and Martley took it upon themselves to advise all the LCDR captains to make the crossing at the fastest but safest speed and that the connecting trains would have to wait. Nor was the price of the journey given as this was regularly increased to pay for maintenance of the fleet. As increases should have been subject to Parliamentary approval, it would seem that they took place at the local level without going through the LCDR Board!

SER responded with an increase in their advertising, emphasising that their service to Paris took 11 hours from Charing Cross railway station. They ran four crossings from Folkestone to Boulogne a week and charged £4.7shillings (£4.35pence) first class and for second class, £3.7shillings (£3.35pence). The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway quickly joined in the advertising war, offering their service to Paris via Brighton and Dieppe. They charged £1.10shillings (£1.50p) for a first class single, £1.2shillings (£1.10p) second class and 15shillngs third class but did make it clear that the time taken to cross the Channel was weather dependent.

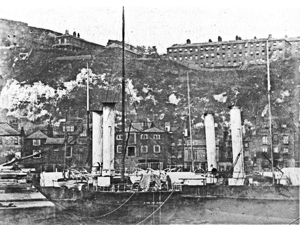

Admiralty Pier before the extension or the Turret were built and showing the open single railway line. The second line was between the original line and the parapet with a narrow platform in between. LS

Regardless of Forbes, Martley and the packet Captains efforts to try and save the LCDR Dover operations, in February 1866 the LCDR Board approached SER with a view to amalgamate the two companies. This was agreed at Board level and the laying of parallel rail lines on Admiralty Pier with a central crossover that enabled both railway companies to use the single platform, was started. At that time ships could berth on either side of Admiralty Pier and SER advised the LCDR Board that a long narrow platform would enabled embarkation and disembarkation on both side of the Pier. The only drawback, and this the the Board members accepted against Forbes advice, was that already the line was open to south-westerly storms that soaked the mail packages, passengers, their luggage and staff who were in attendance! That money would be better spent using the limited space to build a shelter. This was rejected.

Exacerbating Forbes problems in trying to make the Dover packet a semblance of success, were Continental politics and the knock-on effect. Forbes, had advertised the LCDR packet service connection with the Rhenish Railway service to Hanover, Berlin and beyond. Through tickets could be purchased at Victoria station. At the time Germany was a collection of states, many of which had their own monarchies though they belonged to the German Confederation. This had been formed following the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815). To bring to an end the devastating Crimean War (1853-1856) the Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 March 1856 and this gave rise to a spirit of nationalism. Prince Otto Von Bismarck (1815-1898), became the Prime Minister of the largest and most powerful of the States that made up the German Confederation – Prussia – and he exploited this situation. A power struggle followed between the German Confederation and the Austrian Empire that resulted in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the subsequent dominance of Prussia. In June 1866, Forbes issue a press release stating that the service to the German Confederation was suspended and this had a direct negative effect on the demand for cross-Channel travel.

Before the SER-LCDR amalgamation was ratified, the ever increasing financial problems facing the LCDR came to a head and in August 1866 a Committee of Investigation was set up. LCDR were declared bankrupt and James Staats Forbes and William E Johnson – the recently appointed Company Secretary – were appointed joint managers and receivers. The Committee of Investigation published their report on 9 October and in the section on the Dover shipping service, they stated that it was still in debt due to the costs incurred on setting it up from scratch but added that unlike the rest of LCDR operations the sector was becoming financially viable. They particularly noted the Continental Agreement yields and stated that the net profit of the Cross Channel Packet Service for the year ending 30 June 1866 was £17,434 6shillings 9pence. Following the financial collapse, parliament stated that the company was an economic and social necessity and LCDR was restructured. Consequently the company survived but most of the original investors lost their money and the owners of the Fanny Buck did not received any compensation.

On 1 January 1867 the direct rail link between Calais and Boulogne opened, shortening the route between Calais and Paris. Initially only mail carrying trains were allowed on the new route but from 29 March, passenger trains were allowed to use the line. Although the Samphire accident was still fresh in people’s minds, there was a general awareness that Forbes, Martley and the packet ships captains and crew, which included Captain Bennett, had undergone training and the ships surpassed the standards demanded by the Board of Trade.

Edward Prince of Wales circa 1890s. The future King was a regular visitor to Dover as he was very fond of sailing. The Prince of Wales Pier, which he opened, was named after him. Dover Express.

Endorsing this, on Thursday 21 March Christian IX of Denmark (1863-1906) and his entourage crossed from the Continent on the Samphire. He came to England to visit his daughter, Princess Alexandra (1844-1925) the Princess of Wales and her husband Prince Edward (1841-1910) the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII 1901-1910). They were met at Dover by General Frederik Von Bülow (1791–1858) of the Danish Embassy, Lord Alfred Hervey (1816–1875) of the Prince of Wales household, Captain Thomas Cuppage Bruce (1821-1896), the Admiralty-Superintendent for Dover and William Martley.

Edward Prince of Wales circa 1890s, the future King was a regular visitor to Dover as he was very fond of sailing. The Prince of Wales Pier, which he opened, was named after him. In May that year the Prince, with his wife, Princess Alexander, crossed the Channel on the Maid of Kent to attend the Paris Exhibition. On Tuesday 25 June, Augusta Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (1811-1890), the Queen of Prussia arrived from Ostend aboard the Samphire. She spent the night at the Lord Warden Hotel, from where the next morning, before leaving for Windsor to see Queen Victoria (1819-1901), the Queen of Prussia received Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Augustenburg (1831-1917) and Princess Helena (1846-1923) daughter of Queen Victoria.