The Grade II Listed Rifles Monument, on New Bridge twix Camden Crescent and Cambridge Terrace. Alan Sencicle

The Grade II Listed Rifles Monument, on New Bridge twix Camden Crescent and Cambridge Terrace, near the seafront, is a grand granite edifice with bronze decorations. It is 5.5metres (18feet) high and 2metres 6feet) square and is the only one of five examples of free-standing Indian Mutiny group of monuments in England. From the outset the Monument was contentious and remains so.

The obelisk was erected by Officers of the First Battalion of the 60th Rifles to honour their comrades who fell in the Indian Mutiny (as it was then called) of 1857-1859. In attendance was Mayor, John Birmingham and many local dignitaries. With full military honours, the monument was unveiled in August 1861. Unbeknown to the dignitaries and the men of the regiment at the time, the Officers’ had been ordered not to attend. Within days, for reasons unspecified at the time, the Rifles were transferred out of Dover and shortly after, Dover Corporation received a letter from ‘someone on high’ in government demanding that the obelisk be taken down forthwith!

1890 Map showing the Rifles Monument’s location between Camden Crescent and New Bridge near the seafront.

In the 1860s every city and town in the country that thought it had worth, seemed to want to outdo each other with the number and grandeur of the monuments that were being erected within their boundaries. Dover was no exception. The Corporation had drawn up a list of what they too would like and were already on the way to achieving status symbols. Yet here was a beautiful free standing monument, which had not been paid for by the Corporation, and they had received a letter, from central Government, demanding that it should be pulled down!

Edward Knocker (1804-1884) had been elected Town Clerk in 1860 and he was also the Seneschal of the Grand Court of Shepway of the Cinque Ports. In 1861 the Prime Minister, Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784-1865) was appointed the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and the Constable of Dover Castle. As Seneschal it was Knocker’s job to arrange the new Lord Warden’s investiture. Coincidental to the unveiling of the Rifles Monument this was to take place the same month – August 1861 – and with regards to the installation Knocker, Mayor Birmingham and the council were determined to put on a magnificent show.

From 1668, formal installations of the Lord Warden had taken place on Dover’s Western Heights. This had been by the Bredenstone – the ancient Roman Pharos – but the ceremonies had ceased there when the Heights became a military zone. Further, due to the demise of the Cinque Ports, the investitures no longer had the grandeur they once enjoyed and this was the basis of Knocker’s stated reason for it to be a magnificent ceremony. However, at the meeting of the Court of Shepway, when the installation was discussed, the other Cinque Ports called for it to be low key affair and to take place in one of their towns. Knocker, however, successfully argued that Dover was the supreme port and that the full ancient ceremony should be revived. He added that Dover would finance the occasion and won the vote!

The installation took place on 29 August 1861 and to add the notion of supremacy of Dover over the other Cinque Ports, Knocker paid for the Dover Corporation trefoil shape Device adopted by Dover Corporation until 1974 and by Dover Town Council in 1996. Designed by William Courthope (1807-1866), the Registrar of the College of Arms, the bottom left is the traditional Cinque Ports vessel with a forecastle, poop etc. and the bottom right, the historical presentation of St Martin – the Patron Saint of Dover. The shield of the Cinque Ports cheekily surmounts these! Finally, to add even more weight to Dover’s supremacy over the other Cinque Ports, Knocker paid for the former Lord Wardens shields that decorate the Stone Hall in the Maison Dieu – then the Town Hall. The designs were supplied by and carried out by local artist and later photographer, Edward Sclater.

During the proceedings, Knocker told Palmerston of the Rifles Monument debacle but much to Knocker’s surprise, the Lord Warden, responded by saying that as Prime Minister he was aware that the India Office had issued the directive for ‘diplomatic reasons.’ Further he was sure that Dover council would understand and follow any requests that the India Office made. Knocker, was well aware that the East India Company, set up in 1600, was effectively ruling British India. Although, their monopoly over trade had been weakened over time, the Company retained responsibility, under the supervision of the Board of Control, based in London, for the government of India.

The East India Company’s rule of British India was supported by a number of regiments backed by three local divisions that made up the Indian Army. The latter soldiers were predominantly high-caste Brahmins and were frequently treated with contempt by their British colleagues. The sequence of events that led to what was referred to in Britain, at the time this story took place, as the Indian Mutiny are well documented. These days the hostilities that took place between 1857 and 1859 are called the Indian First War of Independence, The Indian Rebellion of 1857, The Revolt of 1857, or The Sepoy Mutiny.

Briefly, there had been growing resentment against British rule and a number of local uprisings. Then on 29 March 1857 a soldier in the 6th Company of the 34th Bengal Native Infantry, Mangal Pandey (1827-1857) at Barrackpore in North Kolkata, was reported as calling upon the men of his regiment to rebel and threaten to shoot the first European that they set eyes on. The Indian officer in command, Ishwari Prasad, was ordered to arrest Pandey but Pandey had proved impossible for Prasad to restrain. After what amounted to a fracas, Pandey was finally arrested and was hung on 8 April. Although Pandey had insisted that he had mutinied on his own accord and that no other person had played any part in encouraging him, on 22 April Prasad was also hung. On 6 May the regiment to which Pandey and Prasad belonged was disbanded with disgrace as a form of punishment. The reaction was what became known as the Indian Mutiny when atrocities were committed on both sides. The officers and men of Rifle Battalions were called upon to fight in the hostilities that followed.

The Rifles origin was as an infantry regiment that had been raised in the Seven Years War (1756-1763) in what was then the British Americas. At the time they were called the Royal Americans and were particularly noted for their abilities in skirmishes and reconnaissance. Highly thought of, the Royal Americans were with General James Wolfe (1727-1759) on 23 January 1759. That day, on the Plains of Abraham close to the township of Quebec, the British routed the French and seized the city. Following the Battle, General Wolfe gave the Royal Americans the motto ‘Celer et Audax’ (Swift & Bold). The regiment was again raised to fight on the side of the British during the American War of Independence (1775-1783). This time they were ranked as the 60th Regiment of Foot and displayed the same abilities as before and were noted for their skill in their use of Baker Rifles.

Following the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815), the expertise of the 60th Regiment of Foot as riflemen were discussed and a contingent from what became the Canadian Fencibles Infantry were brought to Britain. However, the proximity of the United States and their increasing allegiance with France led to a major rethink of this policy. This consideration proved to be well founded when, in 1812, the United States declared war on Britain (See the Francis Cockburn story). In 1797 another Battalion of the 60th Regiment of Foot was raised under Baron Francis de Rottenburg (1757–1832) and his treatise on riflemen and light infantry led directly to the raising of the ‘Experimental Corps of Riflemen’ in 1800.

Under Colonel Coote Manningham (c.1765-1809), the members of this new Corps were hand picked from other regiments and for the want of another name, were initially ranked as the 60th Regiment of Foot. The Corps were given a green uniform and armed with a Baker rifle in place of the smoothbore musket normally issue to army personnel. The men were then put under the command of Sir John Moore (1761-1809) at Shorncliffe camp near Folkestone, where they specialised in skirmishes and reconnaissance and shooting with rifles. They were then gazetted as The Rifle Corps and were the first British unit specialising in light infantry on the European battlefield.

The Corps quickly earned battle honours in the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), including fighting alongside Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) at the battle of Copenhagen (1801) and Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), at Waterloo (1815). Following the Napoleonic Wars, the regiment was renamed The Duke of York’s Own Rifle Corps and then, in 1830, they became King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC). In 1835 the Duke of Wellington’s son, Arthur Richard Wellesley (1807-1884) as Marquess of Douro (1814-1852), was an Officer in the Rifles and was quartered in Dover. The Rifles went on to serve in South Africa, 1846-1847 and the Crimea in 1853-1856. A year later the Rifles were comprised of three Battalions and the King’s Royal Rifle Corps were designated as the First Battalion of the 60th Rifles.

In the May of 1856 a detachment of the First Battalion of Rifles, as they were often cited, were based in Chatham and were ordered to proceed to Turnpike Camp, Saltwood, near Hythe – westwards along the coast from Dover. This was for instruction in the use of the new Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle that had been imported from the United States and was being manufactured in Britain. The course was run by Colonel Charles C Hay, Inspector-General of Musketry, and one of the aspects of the new gun was that the cartridge was wrapped in greased paper which had to cut, usually by biting, to release the gun powder.

Following instruction, the officers returned to the Battalion as instructors and shortly after officers from the Second and Third Rifles Battalions also undertook the course in order to train members of their Battalions. Enfield Rifles were then issued to the First Battalion of Rifles and the other Battalions. A year later, following the news of the rebellion in India, members of the second and third Battalions left for India in small transports, the First Battalion of Rifles were already there. The small transporters each carried up to 350 officers and men, the journey took more than three months. In September 1857 the Fourth Battalion of Rifles were formed and their members joined the other three Battalions in India.

Members of the First Battalion had arrived in India in 1856 and were in Delhi early in 1857 where Ensign Everard Phillipps had been injured in hostilities on 15 January. It had been noted in the dispatches that he had acted beyond the call of duty. The First Battalion were then sent to Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, as part of the second largest of the East India Company garrisons. Following the deaths of Pandey and Prasad the unrest had escalated and on 24 April 1857, Meerut’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel George Munro Carmichael-Smyth (1803-1890), ordered his Indian 3rd Indian Cavalry division to use the new Enfield rifles brought from Britain. Of these men, 85 refused on religious grounds. The Hindus believed the paper surrounding the cartridges were greased with cow fat and the Muslims with pig fat. All 85 were stripped of their uniforms, shackled and imprisoned. Two weeks later, on Sunday 10 May, the gates of the prison were opened surreptitiously and the 85, along with other prisoners, escaped. Shouting what became the famous slogan “Dilli Chalo” (Let’s march to Delhi!) was first raised in Meerut. When the escapees attacked, as it was a Sunday, the First Battalion were at Church Parade and therefore unarmed. Nonetheless, the members managed to escape, collected arms and fought back.

The rebellion then spread throughout much of British India, with the States of Jhajjar, Dadri, Farukhnagar and Bahadurgarh, Amjhera, Shagarh, Biaj Raghogarh, Singhbum

Nargund, Shorapur in the forefront. The States where the majority aided the British were the Independent Kingdom of Kashmir, Kapurthala, Patiala, Sirmur, Bikaner, Jaipur, Alwar, Bharathpur, Rampur and the Independent of Nepal, Sirohi, Mewar, Bundi, Jaora, Bijawar, Ajaigar, Rewa, Udaipur, Keonjhar and Hyderabad. Although the Bengal Army rebelled during the Indian Mutiny (1857-1859), the East India Company’s Madras and Bombay Armies were relatively unaffected and other regiments, including Sikhs, Punjabi Moslems and Gurkhas, remained loyal, partly due to their fear of a return to Mughal rule.

The men of the First Battalion were then marched, under the command of Colonel Jones, nicknamed the ‘Avenger’, to Delhi. 30,000 mutineers occupied the city and the fighting was hard. During the actions the First Battalion held the key position on Delhi Ridge throughout three months of bitter fighting, along with members of the 143rd (Tomb Troop) Battery – Royal Artillery, Queen’s Own Corps of Guides and the Sirmoor Goorhas.

The Guides had marched over six hundred miles to reach Delhi, at the hottest time of the year, and immediately thrown into combat. Within the first hour 350 out of 600 men had been killed. The Company of the Queen’s Own Corps of Guides is now the 2nd Battalion of the Frontier Force Regiment of the Pakistan Army. The Sirmoor Goorhas had been recruited from disbanded soldiers of the Nepalese Army and had been formed at Nahan in Sirmoor State, a small independent kingdom in the Punjab. In September 1857 Delhi was recaptured and for their services the Goorhas were granted the honorary colour of the First Battalion of Rifles. With the decision to number the Gurkha regiments in 1861, the Sirmoor Rifles became the 2nd Gurkha Regiment and permitted to wear a uniform similar to that of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Following changes in policy and amalgamations the Sirmoor Rifle Regiment are now the 1st Battalion Royal Gurkha Rifles.

British Residency, Lucknow, where over 3,000 inhabitants sought refuge, only 1,000 of which survived. Arpan Mahajan Wikimedia Commons

Following the relief of Delhi, the First Battalion of Rifles took in the Oudh Campaign (1857-1858) and in quelling the uprising and siege of Lucknow the capital of present day Uttar Pradesh. The British Residency at Lucknow was centre of all British activities during the siege and for almost 90 days it served as a refuge for approximately 3000 British inhabitants of which only 1,000 survived. Within the walls are the graves over 200 British soldiers who lost their lives during the siege, which took over 18months to suppress. The ruins are a protected monument by the Archaeological Survey of India.

British Ambulancemen and soldiers helping the wounded during the Indian uprising. A. Laby after G.F. Atkinson. Wellcome Images

Following the siege of Lucknow many British senior Army Officers wanted to declare the rebellion over. However, Charles John Canning, Viscount Canning (1812-1862), the Governor-General of India was adamant that until all the rebels were suppressed, the military campaigns should continue. In Britain the Palmerston government had introduced the Government of India Act that had been given Royal Assent on 2 August 1858. On 1 November an amnesty to all rebels not involved in murder. Rohilkhand (given as Rohilcund on Dover’s Rifle Monument) had become a stronghold of rebels that had escaped from Lucknow and the First Battalion of Rifles were deployed in the campaign to relieve the area. This was one of the last actions the Battalion was involved in. On 19 June 1859, Canning, the governor-general declared the hostilities over and the final victory was declared on 8 July 1859.

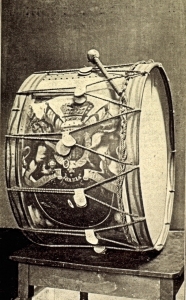

Lucknow Drum presented to Dover on 17 April 1860 but lost during a raid on the Museum during World War II. Dover Museum

The First Battalion of Rifles returned to England in March 1860 and expected to return to their new headquarters at Winchester but due to the potential hostilities on the Continent they were redeployed on Western Heights, Dover. The town gave them a grand welcome and in return, on 17 April, the Battalion took part in the presentation of the Lucknow Drum to Mayor Birmingham and the Drum was placed in the Dover Museum. Sadly, it was lost during one of the German attacks during World War II (1939-1945). However, during the hostilities in India the British Parliament had questioned the way India was being governed and the India Act had led to the Board of Control of the East India Companies being replaced by the India Office. This was to function, under the Secretary of State for India, as an executive office of United Kingdom government alongside the Foreign Office, Colonial Office, Home Office and War Office. Until 1949, India was governed directly this way in the name of the Crown.

During the campaigns in India, 182 Victoria Crosses (VCs), including two posthumously, were awarded to members of the British Armed Forces, British Indian Army and civilians under their command. The most VC’s ever been awarded in a single day was at the Second Relief of Lucknow. The First Battalion of Rifles won twelve VCs and Corporal Nash of the 2nd Battalion while attached to the First Battalion also received the VC, therefore he is included in the list below: The VCs were awarded to:

Ensign Everard Aloysius Lisle Phillipps: 15 January 1857 Delhi, where he died on 18 September 1857. He was posthumously awarded the VC on 15th January 1907. Originally recipients had to survive to receive the VC and this was the earliest a VC that had been backdated. He was originally in the 11th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry but joined the First Battalion of Rifles after his regiment mutinied.

Private Samuel Turner Citation states: ‘On 19th June 1857 at Delhi, when, during a severe conflict with the enemy at night, Private Turner carried off on his shoulder, under heavy fire, a mortally wounded officer of the Indian Service. Private Turner himself was wounded by a sabre-cut in the right arm. His gallant conduct saved the officer from the fate of others, whose mangled remains were not recovered until the following day.’ He was buried at Meerut, India.

Colour-Sergeant Stephen Garvin Citation states: ‘On 23rd June 1857 at Delhi, Colour-Sergeant Garvin volunteered to lead a small party of men under heavy fire to the Sammy House in order to dislodge a number of the enemy who were keeping up destructive fire on the advanced battery of heavy guns. This action was successful. Colour-Sergeant Garvin was also commended for gallant conduct throughout the operations before Delhi.’ He was buried at Chesterton, Cambridgeshire.

Lieutenant Alfred Spencer Heathcote Citation states: ‘From June to September 1857, throughout the Siege of Delhi, during which he was wounded, Lieutenant Heathcote’s conduct was most gallant. He volunteered for services of extreme danger, especially during the six days of severe fighting in the streets after the assault.’ He was buried Bowral, Australia.

Private William James Thompson Citation states: ‘On July 1857 at Lucknow, Private Thompson saved the life of his commanding officer, Captain Wilton, by dashing forward to his relief when that officer was surrounded by a number of the enemy. The private killed two of the assailants before further assistance arrived. Private Thompson was also commended for conspicuous gallantry throughout the siege and he was elected by the regiment to be awarded the Victoria Cross.’ He was buried at Walsall, Staffordshire.

Private John Divane Citation states: ‘On 10th September 1857 at Delhi, Private Divane headed a successful charge by the Beeloochee and Sikh troops on one of the enemy’s trenches. He leapt out of our trenches, closely followed by the native troops and was shot down from the top of the enemy’s breastworks.’ He was buried Penzance, Cornwall.

Bugler William Sutton Citation states: ‘On 13 September 1857 at Delhi, on the night previous to the assault, Bugler Sutton volunteered to reconnoitre the breach. His conduct was conspicuous throughout the operations, especially on 2 August 1857 on which occasion during an attack he rushed over the trenches and killed one of the enemy’s buglers, who was in the act of sounding.’ He was buried at Ightham, Kent.

Colour-Sergeant George Waller Citation states: ‘On 14 September 1857 at Delhi, Colour-Sergeant Waller charged and captured the enemy’s guns near the Kabul Gate. On 18th September he showed conspicuous bravery in the repulse of a sudden attack made by the enemy on the gun near the Chaudney Chouk.’ He was buried Hurstpierpoint, West Sussex.

Private David Hawkes Citation states: ‘On 11 March 1858 at Lucknow, Private Hawkes’ company was engaged with a large number of the enemy near the Iron Bridge. At one stage a captain, Henry Wilmot, found himself at the end of a street with only four of his men, opposed to a considerable body of the enemy. One of the men was shot through both legs and Private Hawkes, although severely wounded, lifted him up with the help of a corporal, William Nash and they then carried their comrade for a considerable distance, the captain firing with the men’s rifles and covering the retreat of the party.’ He was killed in action, Faizabad, India, on 14th August 1858.

Corporal William Nash of the Second Battalion Citation states: ‘On 11 March 1858 at Lucknow, Corporal Nash’s company was attached to the First Battalion and engaged with a large number of the enemy near the Iron Bridge. At one stage a captain, Henry Wilmot, found himself at the end of a street with only four of his men opposed to a considerable body of the enemy. One of the men was shot through both legs and Corporal Nash and a private, David Hawkes, who was himself severely wounded, lifted the man up and then carried him for a considerable distance, the captain covering the retreat of the party.’ He later achieved the rank of Sergeant.

Sir Henry Wilmot 5th Baronet 1831-1901, awarded the VC following action on 11 March 1858 at Lucknow. Wikimedia Commons

Captain Sir Henry Wilmot 5th Baronet Citation states: ‘On 11 March 1858 at Lucknow, Captain Wilmot’s company was engaged with a large number of the enemy near the Iron Bridge. He found himself at one stage, at the end of a street with only four of his men opposed to a considerable body of the enemy. One of his men was shot through both legs and two, David Hawkes and William Nash, of the others lifted him and although one of them was severely wounded they carried their comrade for a considerable distance, Wilmot firing with the men’s rifles and covering the retreat of the party. For his actions he was awarded the Victoria Cross.’ He later achieved the rank of Colonel.

Private Valentine Bambrick Citation states: ‘On 6th May 1858 at Bareilly, Private Bambrick showed conspicuous bravery when, in a serai, three Ghazees attacked him, one of whom he cut down. He was wounded twice on this occasion.’ Later, Private Bambrick was stripped of his VC, following conviction of assault and theft of a comrade’s medals. He committed suicide in Pentonville Prison, London on 1 April 1864 and was buried at Finchley. Nowadays a holder cannot be stripped of the VC no matter what crime has been committed.

Private Sam “John” Shaw Citation states: On 13 June 1858 at Lucknow, an armed man, a Ghazee, was seen to enter a tope of trees and a party of officers and men went after him. Private Shaw, coming upon him, drew his short sword and after a struggle, during which the private received a severe tulwar wound, the Ghazee was killed.

During the hostilities 2,392 British subjects and servicemen died including 170 service from the First Battalion of Rifles. It was to these men that the monument was erected as can be seen from the following inscriptions:

North face:

IN MEMORY OF COMRADES WHO FELL DURING THE INDIAN CAMPAIGNS OF 1857, 1858, AND 1859. ERECTED BY THE 1st BATTALION 60th ROYAL RIFLES AUGUST 1861.

On the East face of the monument the inscription simply says:

OUDE

The West face:

ROHILCUND

While on the South face:

DELHI

with: CELER ET AUDAX (the regimental motto, meaning Swift and Bold) underneath.

Below the cornice at the top are bronze swags on which are hung medals of previous battle honours and the North face additionally has a bronze trophy with a lion’s head mask.

Although no names were recorded on Dover’s Rifle Monument, another at Beonja Khasra, Uttar Pradesh, which was erected by the First Battalion of Rifles, does. This Monument’s inscription states that it is dedicated to members who were killed nearby in action against the mutineers of the Bengal Army on 30 and 31 May 1857. From the inscription, four men died of heat stroke during the fight and one man was wounded on the 31 May and died at Meerat on 4 June 1857.

Following Palmerston, as the Lord Warden, telling Town Clerk Knocker, the reason why the Indian Office had announced that Rifles Monument was to be demolished, the council voted to take over responsibility. Within days the area immediately surrounding the Monument was dug over, planted and a square strong iron fence was erected on deep brick foundations. In September 1871, the Council again received an official communiqué from the India Office ordering them to remove the Monument but Knocker responded saying that the council did not have sufficient funds!

During World War I (1914-1918), on Sunday 23 January 1916, the first night raid on England took place. It was a bright moonlight night with no wind when a German seaplane approached Dover from the west. No sirens were sounded, so the first anyone knew of the raid was when a series of loud retorts woke them up. In all nine bombs were dropped, as the seaplane flew east-northeast. The first bomb landed outside of 9 Waterloo Crescent on the seafront, the second in the middle of the road in front of 7 Cambridge Terrace and the third bomb struck the coping of 1 Camden Crescent. The fourth bomb fell on the roof of the Red Lion public house in St James Street, killing Harry Sladen, the barman at the pub. The next bomb fell on the roof of Leney’s brewery malthouse nearby and the sixth fell on the gas office. The seventh bomb fell at the back of 10 Golden Cross Cottages, Dolphin Lane, wounding young sisters Daisy and Grace Marlow along with Julia Philpott age 71 years. The last bomb fell in front of 9 Victoria Park, breaking windows and shortly after the seaplane disappeared. The third bomb had exploded near to the Rifle’s Monument and it took a large chip out of the edge of the north face.

Rifles Monument after it had been turned into a roundabout in 1936. Note the design of the keep left signs. Dover Museum

In 1936 the first traffic roundabouts were introduced in Dover and one was adjacent to the Lord Warden Hotel while the other was the Rifles Monument. The latter required the change to the shape of the small garden surrounding the Monument from a square to a circle and the iron railings adapted accordingly. The early form of Keep Left signs were erected and can be clearly be seen on the photograph. Following World War II (1939-1945) these were replaced by internally illuminated rectangular traffic bollards that had the main components below the surface. Thus, if a vehicle hit the traffic bollard, the units below the surface were not damaged. These can be seen in the photograph below.

Rifles Monument in 1975 showing the west side (Rohilcund). Note the iconic Dover Stage Coachotel on the left standing on stilts. Dover Museum

At about the time that the Rifles Monument became the centrepiece of one of Dover’s first roundabouts, in the chalk cliffs below the Castle defence work was being carried out. This included the extending and deepening of existing tunnels to provide what would become the headquarters of Fortress Dover, if World War II was declared. Into one of the chalk walls of an excavated tunnel someone has carved KRRC 1936, into the chalk wall. KRRC were the initials of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, the First Battalion of Rifles, pre Indian Mutiny, name that had affectionately been used thereafter by most combatants. In 1941, the government requisitioned all post-1850 iron gates and railings for the War effort and this, it is thought, was when the Rifles Monument’s iron boundary railings were removed.

In 1958, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry joined with the two Battalions of Rifles to form the Green Jackets Brigade. Later, in 1966, the Rifles became part of the Royal Green Jackets. The 1st Battalion of King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) then became the 2nd Battalion Royal Green Jackets (KRRC). On the disbandment of 1st Battalion of the Royal Green Jackets in 1992, the 2nd Battalion was redesignated as the 1st Battalion. In 2007 all the Rifle Brigades and Royal Green Jackets merged to form the Rifle Regiment. This is the largest Infantry regiment within the British Army, and within the Regiment, the former First Battalion of Rifles became the 2nd Battalion The Rifles.

The Rifles Monument remained under the auspices of Dover Corporation until 1974 when following reorganisation it came into the care of Dover District Council. In 1996 Dover Town Council was formed and sometime after 2006 the Monument was transferred to their care. Albeit, some of the councillors claimed that the Monument was not politically correct and called for it to be dismantled. They were erroneously led to believe that it had been transferred to the care of the Dover Society and this is still the claim on some websites.

These days the Monument serves as a reminder that Dover was for centuries a major garrison town. After World War II, the Dover garrison was slowly reduced with the barracks on Western Heights closing in the early 1950s, followed by the Castle Barracks in 1958. Old Park Barracks, near Whitfield, closed in 1991 followed by Connaught Barracks, which closed on Friday 10 March 2006. This last act finally brought to an end over a thousand years of the town’s recorded military history and as the last soldiers stationed there, the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, marched away, people lined the street, many in tears.

Thanks to Alan Lee for his help and encouragement.

Presented: 01 June 2017

For more information on the King’s Royal Rifle Corps contact: http://rgjmuseum.co.uk/