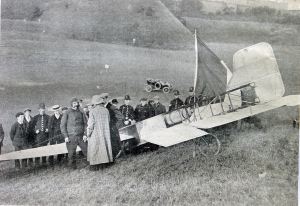

The Dover lifeboat had been in existence since 1837 and the story up until 1929 can be read in Part I. In 1928, Coxswain Adams was in charge and the lifeboat was probably the motorboat William Myatt. In January that year, the Royal National Lifeboat Institute (RNLI) ordered a totally new type of lifeboat from Thornycroft at Platt’s Eyot, Hampton-on-Thames. This was to rescue aeronautic casualties. Since Louis Blériot (1872-1936) had flown across the Channel in 1909 aeroplanes had proved a fascination for affluent adventurers. The development of aircraft during World War I (1914-1918) had increased interest but it was not until the late 1920s, with the easing off of the first interwar economic depression, that interest in recreational flying started to increase. With this the number of casualties increased and to deal with the growing problem the RNLI ordered a new and special lifeboat for their Dover station.

Named Sir William Hillary, after the founder of the RNLI, she was 64-foot, (19.5 metres) x 14-foot (4.7metres) with a draught of 4-foot 9 inches (1.45 metres). The skin was of double teak on oil timbers with steel bulkheads formed into eight watertight compartments. She had two 12-cylinder 375hp engines that gave her a top speed of eighteen knots. On board, there were two cabins with room for 50 people and she was lit by electricity. She had an electric driven capstan, a search light, a line-throwing gun illuminated by tracers at night to a distance of 80 yards, a Morse signalling lamp lit by electricity and wireless telephony that could take and deliver messages over 50miles. She had a plant that could throw jets of fire-extinguishing fluid, oil sprayers at the side for spreading oil to calm down rough water and ropes for hauling the casualties on aboard when it was not possible to use more conventional ways.

The Sir William Hillary was launched on 22 November 1929 and after undergoing trials, including a 4-hour endurance test, came on station before the year had ended. Kept in the Bay, she was instantly available should the summons occur. The crew were ferried out in the motorboat William Myatt, that was kept in the Camber, Eastern Dockyard, where there was always someone on duty. The Sir William Hillary first reported call out was to a collision in the Channel on 2 March 1930. The Japanese 5,500-ton cargo vessel Moke Maru had collided with the coastal vessel Mackvill of London, causing damage to both. The Sir William Hillary escorted both ships into the harbour.

Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) officially launched the Sir William Hillary from the slipway in the Wellington Dock on 10 July 1930. He flew into the former Swingate aerodrome especially for the occasion. By this time, Colin Bryant was the Coxswain but it was not until 2 July 1932 that it was reported the Sir William Hillary had been called to deal with an aircraft in distress. The aircraft, it was said, had come down in the sea between the South Goodwin’s and the Brake Buoy but it was not there when the lifeboat arrived. In fact, the plane had remained afloat and skimmed the surface of the water to Calais sands where she ‘landed’.

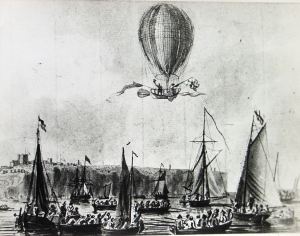

Louis Blériot’s plane 25 July 1909 in Northfall Meadow following his successful flight across the Chanel. Dover Library

Two days before, the Sir William Hillary had undertaken a traditional type of rescue when she went to Herne Bay in record time to go to the aid of the yacht Rosilinde. The lifeboat crew took a casualty on board leaving the other crewmember on the Rosilinde and towed the yacht back to Dover. In October that year, the Sir William Hillary was called out to see if she could find a German mail and freight aeroplane that was reported missing while on a flight from London to Berlin. The plane was a single-engine low winged Junkers that had left Croydon with two crew and no passengers at 20.55hrs. At 21.37hrs, three mayday distress signals in rapid succession were received but the Dover lifeboat searched the area where it was believe the plane had come down without success.

On 9 May 1934, a Wibault low winged monoplane with six passengers on board left Le Bourget aerodrome, near Paris, at 11.15hrs for London. She reported that the visibility was poor, when she passed over the French coast at Le Tréport at 12.10hrs, and was in radio communication with Croydon at 12.19hrs. At that time the pilot said that the plane was 18½miles west-by-south of Boulogne, after that nothing more was heard. The Sir William Hillary searched a wide area but found nothing. On 2 October that year, a twin-engine de Havilland 89 belonging to Hillman airways and with a highly experienced pilot and six passengers on board crashed into the sea off Folkestone. On crossing the Channel, the pilot reported that the visibility was poor and Croydon suspected that he was off course. The Folkestone lifeboat recovered the bodies and the Dover lifeboat searched the area to collect evidence as to the cause of the accident.

The Channel port of Boulogne has the oldest lifeboat society on the Continent. Alexandre Adams and John Larkins, an Englishman, founded the Boulogne Société Humaine, and from the start, the committee consisted of half French and half Englishmen. On 12 August 1934, Coxswain Bryant and the crew of the Sir William Hillary attended the naming of a new lifeboat there, the Alexandre et Louis Darracq. Also at the celebration was the crew of the Calais lifeboat, the Maréchal Foch, who had also been at the official launch of the Sir William Hillary.

Alexander Korda (1893-1956) the film director was making the film The Conquest of the Air (1936), starring Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) and included the events leading up to the first successful cross Channel balloon flight by Jean-Pierre Blanchard and Dr John Jeffries on 7 January 1785. The balloon in the sequence being filmed, took off from St Margaret’s Bay on the afternoon of 7 August 1935 and as the cameras’ rolled the balloon travelled westwards. Off Folkestone, the balloon suddenly collapsed and landed in the sea. The Sir William Hillary was called out but was not required as the balloon was towed ashore by a speedboat accompanying the flight. On board was French aeronaut Charles Dolfus (1893-1981) and the balloon collapsing was in the script!

In 1937, Dover Lifeboat Station celebrated its centenary and the following year, on 5 June, the Coxswain and crew were awarded £55 for salvage services rendered to the yacht Nirvana. Salvaging is not part of a lifeboat crew’s job description and this only happens in very rare instances. Six months later, on 13 January 1939 the honorary secretary of the Dover lifeboat station, J R W Richardson, was awarded inscribed binoculars by the RNLI. World War II (1939-1945) was declared on 3 September that year adding to the dangers the crew of the lifeboat faced. On 26 November 1939 the trawler, Blackburn Rovers, with 16 men on board, was on anti-submarine patrol near Dover. A southwesterly gale was blowing when a wire fouled her propeller. Although the crew dropped anchor this failed to hold and Blackburn Rovers drifted towards a minefield.

At 10.00hrs Sir William Hillary, under the command of Coxswain Bryant and with Lieutenant Richard Walker, the Admiralty Assistant Harbour Master, went to the rescue. Lt. Walker had a chart showing the minefields, which showed that the stricken ship was on the edge of one. They managed to rescue the 16 crewmen along with important documents before scuttling the ship and holding their breaths. If she landed on a mine, she would have blown them all to smithereens. For the rescue Coxswain Bryant was awarded the RNLI Silver Medal, with Lt Walker along with Second Coxswain Sydney Hills and the two motor mechanics W. L. Cook and C. R. T. Stock the Bronze Medal. The other members of the crew, A. F. Barton, S. Walker, H. W. Hadley, E. J. Le Gros and J. E. Clarke were each awarded the RNLI Thanks on Vellum.

In early 1940, to deal with an increasing number of rescues a Norfolk and Suffolk class lifeboat, Agnes Cross, came to Dover. The Sir William Hillary left Dover that year and was later sold to the Admiralty. During her ten years tenure, she was responsible for rescuing 29 lives. Due to the increasing hazard of mines, the William Myatt and the Agnes Cross left Dover the following year for relocation. Dover lifeboat station closed for the remainder of the War.

The station opened again on 29 May 1947 under the command of Coxswain Johnny Walker. The H F Bailey II, a 45 foot (13.72 metres) Watson class lifeboat, built in 1924, was brought from Cromer and renamed J. B. Proudfoot and based in the Camber at the Eastern Dockyard. On the morning of 28 June 1947, there was thick fog and the steamer Heron of Piraeus had been in collision with the Danish vessel Stal and sunk some 14miles east-south-east of Dungeness. The survivors had been picked up by the Suavity and J.B.Proudfoot met her two miles off Dover where the 23 survivors and the ship’s pilot were transferred and brought back to Dover.

There was a storm blowing on the morning of 21 August 1948 when the crew of the J. B. Proudfoot received a call from the 2,905-ton steamer Baron Elibank saying that they had spotted a rowing boat that might be in trouble. Quarryman Robert Salisbury age 26 of no fixed abode and miner Kenneth Gant age 24 from Wakefield, Yorkshire, were suffering from exhaustion when they were rescued and brought back to Dover. On shore, it became evident that they had stolen the £60 rowing boat from the town’s beach so it was the police who welcomed them when the lifeboat returned to the Camber! The following day the two men, having recovered from their ordeal at sea, pleaded guilt to stealing the boat and were sentence to one month in prison. This was one of the six rescues that the J. B. Proudfoot was involved in during her two-year service at Dover.

In June 1948, it was announced that one of three lifeboats presented by South Africa to the RNLI would be stationed at Dover. Aptly named Southern Africa she was the first ‘Barnett‘ class lifeboat to be built after World War II and arrived in 1949. Built by Rowhedge Ironworks, Wivenhoe near Colchester Essex, she was 52-foot (15.89 metres) x 13-foot 6inches (4.12 metres), powered by two 60 BHP ‘VE6’ diesel engines. The Southern Africa was officially named by Edwina Countess Mountbatten of Burma, (1901-1960) and the High Commissioner for South Africa on 16 September 1950.

By this time, on receipt of a distress call, Dover Port Control would electronically fire two maroons from the roof of the Clock Tower to call out the lifeboat crew. As the crew lived and worked in and around the town the lifeboat station van, at certain fixed points, would collect those who did not have transport. On arrival, the men put on the protective clothing and life jackets, which were hung ready for use, and as there was always a man on station, they boarded the prepared lifeboat.

Just before midnight in September 1951, there was a gale blowing and Coxswain Johnny Walker was on station when he spotted a small yacht, evidently in trouble, just off the Eastern Arm. He called up Port Control and the maroons were fired but without waiting for the van bringing the last two crewmembers, the Southern Africa put out. The yacht was broadside on to wind and seas and within 30 yards of the cliff. When the lifeboat reached her, Coxswain Walker laid the Southern Africa alongside. A rope was thrown, made fast and the lifeboat pulled the yacht clear of danger. For this, Coxswain Johnny Walker was awarded the bronze medal for gallantry.

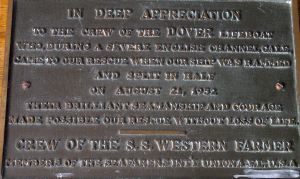

The 7,239-ton liberty ship Western Farmer was hit by the 11,732-ton Norwegian tanker Bjorgholm near the Goodwin Sands in August 1952, and her bow section sank almost immediately. A distress call was made and the Southern Africa rescued the captain and the 13 crew. The remaining part of Western Farmer drifted in the Channel and with several thousands of pounds of goods on board a number of French tugs honed in for salvage. Two succeeded in towing what remained of the Western Farmer towards Calais but due to the weight of the cargo, the weather and the strong currents the wreck foundered and sank. At the Dover Lifeboat station there is a plaque from the crew of the Western Farmer, giving thanks to the Dover crew who rescued them.

Fog was a feature of the weather in March 1953 and there were a number of collisions that the Dover lifeboat attended. On Friday 20 March, the visibility was down to zero when the call was received that 7,254-ton British steamer Statesman and the Greek steamer Flight-Lieutenant Vassiliades RAF had collided two miles south of Dover. The Southern Africa put to sea but after four hours search, were unable to find either vessel. As she returned to port, the Coxswain received a radio message saying that neither vessel needed assistance. Hardly had the crew time for a cup of tea when they were called out again. The 857-ton motor vessel Sparnestroom had radioed that she had collided with the 4,877-ton German steamer Waldermar Sieg four miles off Dover. By the time the lifeboat arrived the Sparnestroom appeared to be sinking but the Waldermar Sieg had taken off all the crew, excepting one. There was no sign of the missing crewman so the lifeboat took the 15 rescued crewmembers back to Dover.

The badly damaged Sparnestroom did not sink; instead she drifted down the Channel and next day was off Dungeness. On the deck, trying to attract attention, was the missing man the greaser Cornelius Shuurman. He had been below at the time of the accident! The ship, with some of her crew on board, was taken in tow by the Stentor. It was agreed that Cornelius would stay on the Stentor and return with both ships to Amsterdam. Later the Stentor radioded to say that the Sparnestroom had broken adrift and was missing but before the lifeboat was out of the harbour she radioed again to say that the Sparnestroom had been located and that her crew were on the Hector. The Dover Harbour Board tug, the Lady Brassey went to help and brought the Sparnestroom into Dover where the beleaguered ship was beached. She was later pumped out, received temporary repairs and returned to Amsterdam.

Every year the lifeboats rescue people cut off by the tide, climbing the cliffs or fall/jumped off the top of the cliffs around Dover – Langdon Cliff – looking towards South Foreland. AS 2011

In March 1954 Miss Ursula Upjohn, the sister of judge the Brigadier Gerald Ritchie Upjohn, Baron Upjohn (1903-1971), was exercising her collie dog Trixie on the top of the cliffs at St Margaret’s Bay. The dog fell to the beach below and Miss Upjohn went down to her and was joined local fisherman, Jim Atkins. For four hours, Miss Upjohn stayed with her dog and when the tide was coming in Atkins went to get help. The coastguards called the Dover lifeboat and both they and Atkins directed the Southern Africa to the stranded lady and her dog who were rescued by dinghy from the lifeboat. Sadly, Trixie never regained consciousness and died. Every year the lifeboats rescue people cut off by the tide, climbing the cliffs or fall/jumped off the top of the cliffs around Dover. Of interest, sometime after this rescue and following the gift of a substantial donation, Rother RNLI – East Sussex, had a lifeboat named Ursula Upjohn and Dungeness RNLI a lifeboat named Alice Upjohn.

On 8 September 1954, Ted (Edward) May a 44-year old father from Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, attempted to swim the Channel from Cap Gris Nez, France, to Dover without an accompanying boat. To provide sustenance he towed a tyre inner tube full of provisions topped with a mast decorated by coloured electric lights attached to a large battery and a notice, ‘Lone Swimmer’. This was his second attempt in two weeks. On the first occasion a passing timber boat had picked him up about six miles from the French coast. When nothing was heard of Mr May, the Dover lifeboat joined the Walmer lifeboat in a search for the Lone Swimmer, but without any luck. Some weeks later, Mr May’s body was washed up on the Dutch coast. Following the death of lone swimmer Ted May, the Channel Swimming Association insisted that a pilot boat equipped to deal with emergencies must accompany all registered swims.

In 1955, the Dover Lifeboat Ladies Guild was formed to raise money for the service. In 1987, Nora Post received the RNLI Silver Badge and the RNLI Gold Badge in 1999. In 2002, Muriel Sharp also received the RNLI Gold Badge. However, it was not until 1996 that the Dover lifeboat had its first female crewmember, nurse Kendal Beasley. The gales in 1955 took their toll on shipping and the lifeboat was called out several times. On one occasion, it was to take off a member of the crew of the South Goodwin lightship who had injured his arm.

Early in 1956, the Southern Africa was involved in rescuing ten people from yachts during hurricane force winds. Then in May, she took the captain’s wife and small son off the 379-ton Dutch coaster Prins Bernhard. The ship had been damaged in a collision during thick fog with the German 3,098-ton ship Tanger. In July that year, the 2,613-ton French ship Dione was in a collision with the 8.000-ton Liberian Michael C that was undergoing trials. The lifeboat, DHB tug Lady Brassey and the pleasure steamer Queen of the Channel – packed with tourists – went to the rescue.

The Lady Brassey managed to separate the two ships and the crew of the Dione, having taken to her lifeboats, returned to their ship. She had almost lost her bow so was lashed, at the side, to the Southern Africa and the Lady Brassey towed them to Calais. At the end of that year, the Southern Africa was returning from the South Goodwin Lightship, with a BBC television crew on board, when she picked up distress signals from a fishing boat. The television crew lost no opportunity to film the rescue, which was televised in March 1957. For his services that year, Coxswain Walker received an RNLI silver medal for gallantry from Lady Mountbatten.

In August 1959 two of Dover’s lifeboat men, Arthur Liddon and John Clarke, dived into the sea in mid Channel from the Southern Africa in order to rescue 35-year old Miguel Mendez. Mendez was one of the 21 crew on the Spanish cargo vessel Naranco that had sank off Dungeness following a collision with the 8,684-ton Panamanian ship Goldstone in thick fog. Nineteen of Naranco‘s crew had been picked up by the Goldstone. Of the two missing men, the Southern Africa found Mendez clinging to an upturned ship’s lifeboat and had been for two hours. He was so exhausted that he had to be lifted on board the lifeboat. The other crewmember was not found.

Basil D Ebsworth was appointed the new Secretary of Dover Lifeboat in February 1960 and according to the RNLI regulations was responsible for giving the order for the lifeboat to be launched. The Coxswain, Captain Johnny Walker, did not agree saying that ‘when I get a report of a ship in distress, all I can think about is getting cracking.’ The Secretary, however, stuck to the rulebook and in August 1960, matters came to a head. Coxswain Walker resigned along with deputy Coxswain John Clarke, bowman William Clark and relief mechanic George Hawkins – father of Tony and Richard Hawkins who feature later in the story.

Alfred ‘Darky’ Cadman was appointed Coxswain and in November 1960, the Southern Africa rescued 16 anglers taking part in a fishing festival at Folkestone. They had been disappointed with their catch off the pier and decided to charter a boat and fish further out. However, a fuel blockage and strong winds swept them out to sea and the Dover lifeboat was called out. They found the men and towed the boat back to Folkestone. Rescuing crews off boats with an inadequate supply of fuel, engine problems or inadequate training/inexperienced crew is another regular occurrence for Dover lifeboats.

The 2,811-tonnes Yugoslav steamer Sabac, and the 6,223-tonnes London steamer Dorington Court, were in collision during thick fog six miles off Dover in January 1962. The Sabac was almost sliced in two and sank within five minutes. One of the first vessels on the scene was the British Railways train ferry, Hampton Ferry, under Captain Norman Dedman, which was sailing between Dover and Dunkerque. The Dover lifeboat went out, as did the DHB tug Diligent and the Walmer lifeboat. The crew of the Dorington Court and the Hampton Ferry, with the help of passengers, looked for people in the water. The Hampton Ferry picked up the master, first officer and a member of the crew of the Sabac together with four bodies, all of which had died from exposure. The Dorington Court found three survivors but one later died. Even though the wind picked up to gale force 8, the Southern Africa lifeboat crew spent a further 12-hours looking for bodies, picking up five and the Walmer lifeboat picked up seven. Of the Sabac‘s crew of 33, only five survived.

Fog was again a problem in March 1962 when the 4,153-ton Danish cargo ship Kirsten Skou was in collision with the 4,716-ton German motor vessel Karpfanger. The Kirsten Skou sank within twenty minutes but the crew of 38 managed to take to the boats and the German ship picked them up. The crew of the Kirsten Skou were transferred to the Southern Africa and brought to Dover. Gales closed Dover Harbour in November 1962 during which the East Goodwin Lightship broke away from her moorings. She drifted for about four miles until the 7-man crew managed to anchor her. The Walmer lifeboat went to her aid and stood by until she ran low on fuel and then called the Dover lifeboat to take over. The Southern Africa stayed until the Ramsgate boat came to relieve her so the Dover lifeboat could deal with other emergencies, of which there were many.

When the Panamanian ship Carmen was in collision with a Turkish ship in June 1963, there was again thick fog. The Carman, with 23 crew on board, sank but 21 members of the crew were picked up and brought to Dover in the Southern Africa. A German lifeboat, the Georg Breusing, whose crew were in the UK attending a national lifeboat conference, helped the Walmer lifeboat in searching for the two missing crewmembers. During March 1965 there were at least two collisions in the Channel one of which involved German motor vessel 1,056-ton Katherine Kolkmann and British steamer 923-ton Gannet. The Katherine Kolkmann sank within 15 minutes and the Gannet rescued all but one of the crew of 15. However, the captain was badly injured and had to be airlifted to Buckland Hospital, Dover. The Southern Africa brought the remainder of the crew back to Dover and they were taken to the Seaman’s Hostel. The missing man was not found.

During gale force winds and heavy seas on 2 December 1966, the Varne lightship started dragging her anchors and the Southern Africa along with two Trinity House vessels went to her aid. The Trinity House vessels were unable to move the lightship and were concerned the ship might be driven onto the Varne bank so asked the Dover lifeboat to stand by. The weather continued to deteriorate and the commander of the Trinity House vessel Siren asked Coxswain Cadman to take the crew off. They made their first attempt at 10.42hrs and one person on each attempt with the lifeboat backing off and steadying between each man, by 11.35 all seven-crew members, including the captain, were safely on board. A letter of commendation was sent to Coxswain Cadman and the crew for their arduous and skilful service.

Coxswain Cadman was succeeded by Coxswain/Mechanic Arthur Liddon in 1967. The Faithful Forester replaced Southern Africa that year. The Faithful Forester was a Waveney Class 44 foot (13.5 metres) lifeboat built by Brook Marine of Lowestoft and capable of 15 knots. As her name implied, she was funded by the Ancient Order of Foresters. The Princess Marina of Kent (1906-1968), as President of the RNLI, named the Faithful Forester, on 26 July 1967. The Princess’s husband, Prince George, the Duke of Kent (1902-1942) had been the President of the RNLI from 1936 to 1942 and their son, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, succeeded Princess Marina, as President in 1969. This was the Princess’s last naming ceremony for the RNLI before her death.

At 04.00hrs on 11 January 1971, there was a tremendous explosion off Folkestone that broke windows all along the coast. There had been a collision between the 20,500-ton Panamanian Tanker Texaco Caribbean and the 11,900-ton Peruvian cargo ship Paracus about five miles off Folkestone. Visibility was fair. The explosion was on board the Texaco Caribbean, which had discharged part of her cargo of petro-chemicals at Terneuzen, near Flushing and the remainder at Canvey Island. She was bound for Trinidad when the accident happened. The Texaco Caribbean had a crew of thirty and after she was sliced in half, 21 had managed to get into a lifeboat. The Norwegian ship Bravagos picked them up. The Folkestone trawler, Viking Warrior, picked up another crewmember and the Faithful Forester recovered three bodies taking them and the 21 crewmembers to Dover. An oil slick 11 miles long, approximately 250 yards wide and 6 inches deep formed. This was the worst oil pollution to reach the Kent coast and sackfuls of seabirds covered in oil were collected.

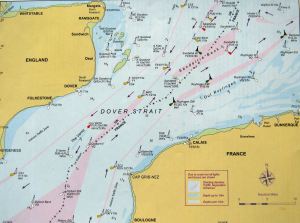

The bow half of the Texaco Caribbean sank within minutes but it was not for another ten hours before the stern sank. The 2,695-ton cargo ship Brandenburg hit this the following day with a loss of 21 lives and on the 27 February 1971, the 2,371-ton cargo ship Niki hit the wrecks with the loss of all 22 crew. The resulting inquiries led to the formation of the Dover Strait Traffic Separation Scheme. This divides the East and Westbound Channel shipping lanes by a separation zone and created inshore traffic zones on both sides of the Channel. At about the same time, limited radar surveillance was introduced at the then Coastguard Station at Leathercote Point, St Margaret’s Bay. The coastguard station was replaced in 1979 by a new, purpose built operations centre at Langdon Battery, overlooking the eastern end of the harbour. In the late 1970s the Channel Navigation Information Service was instigated which monitors and polices all ships in the Channel making it mandatory for all ships over 300-tons, to give an account of themselves. The Coastguards also co-ordinate the Search and Rescue System that includes air-sea rescue and lifeboats.

Barry Sheppard was a member of the lifeboat crew and he and his wife Margaret had a flat at East Cliff. On the night of 27-28 January 1974, the wind was shaking the building and the waves were pounding the promenade in front of the house. Because of the proximity to the lifeboat, Sheppard was often first aboard. On that night he was awaken by the maroons at 01.30hrs and could see the red flare above the Southern Breakwater close to the Eastern entrance to the harbour. There was a southwesterly force 9 gale blowing so the likelihood of the casualty being swept on to the rocks at Langdon Bay was a certainty. Sheppard rushed to the Faithful Forester and fired up the engines, John ‘Jack’ Smith soon joined him followed by second Coxswain Tony Hawkins. After Sheppard had told the others what he had seen Tony contacted the secretary – as the RNLI instructions demanded – and also the Coxswain Arthur Liddon. And then waited for two other crewmembers to arrive in order to comply with regulations. Sheppard, however, concerned over the casualty, wanted to put to sea immediately. After a short deliberation, Hawkins complied with Sheppard and the lifeboat left for the casualty.

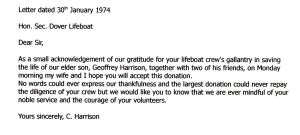

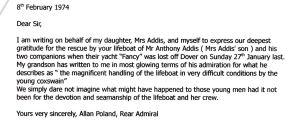

Letter from one of the parents of the crew of the Fancy of Falmouth that foundered in Langdon Bay on the night of 27-28 January 1974

The seas were tremendous and as typical off the Eastern entrance, the waters were confused creating giant waves in all directions. Once out of the entrance the lifeboat crew could see a classic wooden yacht with no sails and three crewmembers sitting in the cockpit with seawater up to their knees. The boat, Fancy of Falmouth, was under Langdon Cliff and almost on the rocks. When close enough, the lifeboat crew threw a line and one of the yacht’s crew clambered forward to catch it and tied it around the mast. Hawkins moved the Faithful Forester forward to tighten the tow but the vessel was too waterlogged to move. The Fancy of Falmouth crew using the towrope and with the help of lifeboat crewmen, Sheppard and Smith, clambered into the well deck of the Faithful Forester.

Letter from one the grandparent’s of the crew of the Fancy of Falmouth that foundered in Langdon Bay on the night of 27- 28 January 1974

The last of the three from the yacht, Fancy of Falmouth, cut his shin on a propeller when he was partially swept under the boat. Once aboard the ambulance service was informed and the Faithful Forester returned to the pen where the casualties were taken to hospital. The rescue was recorded but no details were given as the three lifeboat crew had broken the RNLI rules of not gaining permission from the Dover-RNLI secretary and had gone out with two lifeboat crewmembers short. However, the parents of the three young people whose lives they had saved thought differently and wrote to Dover-RNLI in gratitude. Thus, in some respect, vindicating ex-Coxswain Johnny Walker and his three comrades, one of who was the father of Tony Hawkins, who had resigned in 1960 because of the red tape.

In January 1975, the RAF Search and Rescue helicopter was returning to Manston, on the Isle of Thanet, when one of the crewmembers saw what appeared to be a weak light in the Channel. It was windy and the sea was rough but on closer inspection, the light appeared to come from a small boat with a sail. They called out the Dover lifeboat but when the Faithful Forester arrived at the scene the yacht, Golden Sands, appeared to be abandoned and in danger of capsizing. Then one of the lifeboat crew spotted a pair of eyes, Coxswain Liddon called out and slowly 14 men came up from down below. They looked in a very sorry state and were obviously suffering from seasickness. It soon became evident that the yacht’s engine had broken down so the men were taken on board the lifeboat and the boat towed into Dover. On arrival at the port, the men were taken into police custody and charged with contravention of the Immigration Act.

The Golden Sands was moored in Dover but the owners of the £3,000 yacht were not traced so the lifeboatmen sought appraisement and sale of the vessel. A hearing was held at the Admiralty Court in March 1975, the order was granted and Coxswain Liddon and four members of the crew were awarded £200 salvage. Then, after a few moments thought, the judge increased the award to £300, saying that the owners of the yacht would have received £900. It is unusual for lifeboat crew to claim salvage as the service is primarily to save lives but at the time no one had claimed the boat. Sometime later, six men connected to this case, were arrested for contravention of the Immigration Act.

On 1 December 1975, the Faithful Forester went to the assistance of the Cypriot coaster Primrose adrift with steering problems in rough weather. Coxswain Liddon and his crew guided the stricken vessel back to Dover, an operation that took 8 hours. For the rescue, he received the Silver Medal for gallantry and Second Coxswain, Tony Hawkins, the Bronze Medal. Richard Hawkins, John ‘Jack’ Smith and Gordon Davis were awarded the RNLI ‘Thanks on Vellum’. In November 1976, the Faithful Forester was called out by the captain of the Bonnington, to help search for a couple from the yacht Scamperer feared run down by a ship during the night. The captain of the Bonnington was HRH Charles, Prince of Wales. The crew of the Faithful Forester undertook a wide and lengthy search but except for wreckage, nothing was found.

Painting (detail) of the RNLI Lifeboat Rotary Service presented to HRH Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother on naming 30.10.1979. RNLI-Dover

Coxswain Arthur Liddon handed over to Tony Hawkins in 1978 and in 1979 the Faithful Forester left Dover. If my sums are correct, she was involved in the rescue of nearly 300 lives! On 30 October 1979, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, officially named Dover’s next lifeboat, Rotary Service. Costing £300,000, she was funded by Rotary International of Great Britain together with bequests from M. Redgate, M. Fowkes and D. Craig. Capable of nearly 20knots, Rotary Service was one of only two Thames Class lifeboats. Built of steel she was 50 foot long (15.25 metres) and powered by twin General Motors diesel engines.

In 1981 retired Coxswain Arthur Liddon died, he had been in the RNLI service for 31 years. In August that year, 10 police officers from Dover rowed across that Channel in a whaler to raise money for the Dover Lifeboat. The following June the Rotary Service rescued six men and a boy from the French trawler Armand Eche, that had been under tow. The trawler sank shortly after. Captain Stanley Williams, of the Gateway, a Trinity House Pilot for 44 years, retired as Chairman of the Dover RNLI in 1982, he was succeeded by bank manager Roy Pain who was also the Dover RNLI Treasurer.

At this time, there was a major expansion of the Eastern Docks. The first part of which was completed by 1984 and cost £9.2m. At that time the second part of the scheme had already started that included reclaiming 4 hectares of the Camber, where the lifeboat was moored and costing £5.1million. A new home was found for the lifeboat in the Tug Haven at Western Docks and DHB workshops were converted into a boathouse at a cost of £30,000.

Shortly after 1600hrs on Saturday 30 March 1985 the Hovercraft, Princess Margaret, with 370 passengers on board – mainly French schoolchildren – was entering by the Western entrance. At the time, there were strong winds and heavy seas and she hit the Southern Breakwater. A number of passengers were thrown into the sea and members of the crew jumped in to rescue them. Both the Rotary Service and the tug Dexterous were prompt on the scene. After rescuing those in the sea the next job was to rescue the passengers still in their seats, none of which had seatbelts, and suspended over the tempestuous sea. The lifeboatmen ran a rope through the Prince of Wales Pier to steady the Hovercraft, and then putting Rotary Service on the damaged side of the Hovercraft, carefully helped the stricken passengers to safety. Altogether, the lifeboat crew worked for eight hours taking off 175 passengers and 8 crew as well as searching for the missing. Four passengers died in the accident.

The Dover Strait was calm during the night of 14 August 1986 when three Romanian seamen on the 8,100-ton Paulus, threw a dinghy into the water. The ship was en route from Turkey to Sweden and all was quiet on board when they dived into the water. However, it took them nearly an hour to locate the dinghy and when they did, the men climbed on board and sent up distress flares. These were seen by a cable laying ship, which alerted the coastguard and the Rotary Service was called out. The three men were suffering from exposure when they were picked up. On arrival in Dover they asked for asylum.

Dover Lifeboat service celebrated its 150 anniversary in 1987 with a ball at the Town Hall. This was also the year of the Great Storm that devastated the south coast of England. This happened during the night of 15/16 October when wind speeds of over 100mph were recorded. Shortly after 05.11hrs Rotary Service, with Second Coxswain/Mechanic, Roy Couzens at the helm was about to go out to the help of the 1,600-ton Bahamian registered bulk-carrier Sumnia, in trouble outside the Admiralty Pier. However, it was found that there was rope twisted around the lifeboat’s propeller and divers Cook and Gill, under difficult condition, cleared the problem. The seas were heavy, as a hurricane force 12 on the Beaufort wind scale was blowing, when they eventually headed out to the casualty.

On arrival, Second Coxswain/Mechanic Couzens, manoeuvred the lifeboat to within twenty feet of the distressed vessel and two men wearing lifejackets could be seen on the Sumnia. An enormous wave hit the distressed vessel sweeping the two men off the deck and battling against huge waves, the crew pulled one of the men aboard the lifeboat. They then rescued the second, by which time the Sumnia was breaking up and four men were still unaccounted for. As the lifeboat crew were searching for them in the rough seas, the Rotary Service suddenly dropped from the top of a 60 foot (18.2metres) wave and Roy Couzens was thrown violently. Obviously hurt he carried on. By this time, the lifeboat had been joined by the DHB tug, Deft, and launches, George Hammond II and Verity. The crew of the Deft rescued a third sailor and the lifeboat crew pulled out of the sea a fourth man. Initially he seemed to be dead but artificial respiration was successfully applied and he recovered. The lifeboat then headed back to base with the three rescued men on board.

After leaving the rescued men with their colleagues, the lifeboat headed back out to sea to look for the two missing men. However, as they did Second Coxswain/Mechanic Couzens suddenly felt unwell and Acting Second Coxswain Michael Abbot took the helm. Roy Couzens’s condition deteriorated so Michael Abbot returned the Rotary Service back to base. From there Roy Couzens was taken to hospital where it was diagnosed that he had suffered a heart attack. The remainder of the lifeboat crew returned to duty and the bodies of the master and the first mate of the Sumnia were found.

For outstanding seamanship Roy Couzens, received the RNLI’s Silver Medal. Each of the crew, Michael Abbot, Geoffrey Buckland, Dominic McHugh, Christopher Ryan, Robert Bruce and Eric Tanner received the Bronze Medal. Roy Couzens also received the Maud Smith Award for the most outstanding Act of Lifesaving that year. For their part in the search and rescue operation, the Master and crew of the DHB tug Deft, received a Letter of Thanks, signed by (George) Iain Murray, the 10th Duke of Atholl (1931-1996). The crews of George Hammond II and Verity received letters of thanks from the Director of the RNLI, Lt Commander Brian Miles. Letters of Thanks were also sent to divers Cook and Gill, who had cleared the rope from the lifeboat’s propeller shaft. The Rotary Service crew won the Silk Cut Nautical Award for Rescue that year.

Fausta Mareno, age 41, was one of the 89 official attempts to swim the Channel in 1989 when her escort boat, Mary Mayne, noticed that she had suddenly stopped swimming. They hauled Fausta out of the water and called the coastguard who called out the lifeboat. The Rotary Service arrived within 30 minutes and resuscitated Fausta and she regained consciousness. The lifeboat was taking her back to Dover when Fausta loss consciousness again from which she never recovered and was pronounced dead on arrival in Dover. At that time, Fausta was the fourth person to die attempting the crossing since Captain Matthew Webb first made the swim in 1875.

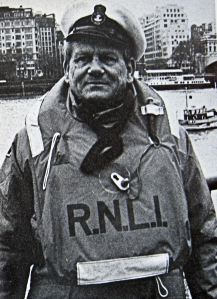

Rotary Service was involved in many outstanding rescues but in March 1997, City of London II replaced her. A Severn class all weather lifeboat the City of London II was funded by the City of London Branch Centenary appeal plus legacies from E. Horsfield and G. Moss and cost £1.5m. The City of London II is 17 metres (55.78 feet) in length and 6 metres (19.69 feet) beam. Her top speed is 25 knots and displacement 44-tonnes. She is fitted with state of the art technology including a fixed camera for filming rescues for training and publicity purposes. She carries a crew of seven, coxswain, mechanic, navigator and four, which includes a doctor.

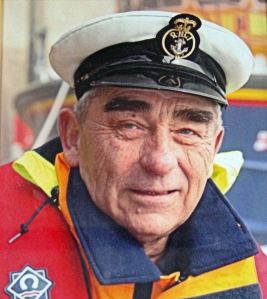

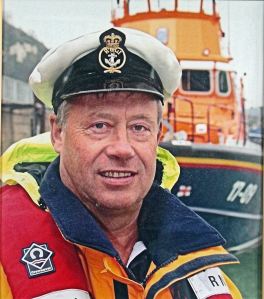

Her crew, under Coxswains Tony Hawkins (1978 – 1999), David Pascall (1999 – 2003), Duncan Mackay (2003 – 2007), Stuart Richardson (2007- 2010) and Mark Finnis (2011-present) have dealt with a variety of catastrophes with the courage and professionalism of their forebears. Further, 1998 saw Coxswain/Assistant Mechanic Tony Hawkins awarded the MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list. The following year he retired as a lifeboat man but was still actively involved in Dover’s lifeboat organisation.

During the early hours of 24 August 1999, 17 miles northeast of Margate, the Cruise liner, Norwegian Dream, collided with the container ship, Ever Decent. The 50,764-tonne Bahamian registered Norwegian Dream built in 1992, carrying 2,400 passengers and 600 crew, sustained damage to the bow. On the bow was the debris from some 20 containers off the container ship. Further damage along her starboard side included a smashed lifeboat yet, amazingly, there were few injuries with only approximately 20 persons being treated by the ship’s doctor. The 52,000-tonne cargo ship Ever Decent registered in Taiwan, owned by the Evergreen Marine Corporation and with a crew of 40, was holed. The collision also caused a fire lasting well over 24 hours in some of the containers and produced noxious fumes. Tugs equipped with fire fighting equipment were deployed to control the blaze and the City of London II was called to the scene along with the lifeboats from Ramsgate and Margate. Coxswain Dave Pascall and his crew spent 37 hours ferrying firemen and their equipment to and from the blazing ship. The Norwegian Dream came to Dover where her damage was assessed.

In 2000, the lifeboat moved to a new berth by the Crosswall and a generous legacy from relatives of a deceased local enabled a new £513,000 boathouse to be built nearby. That year, to mark the 40th anniversary of the Dunkirk Evacuation, 40 little ships left Granville Dock for Dunkerque. They were escorted, amongst other vessels, by the City of London II. Ferries and hovercraft kept a respectful distance. In July that year Michael Murphy a 14-year old boy from Birmingham on a school trip to France, was left behind at a French Service Station north of Lyons. However, it was eight hours later, when the school party were aboard the Cross-Channel P&O Ferry Pride of Dover, that it was discovered he was missing. The teachers informed the captain and an air-sea rescue operation, costing approximately £100,000, was launched including the Dover lifeboat. Just over four hours later this was called off when it was reported that Michael had been found by the French police in the early hours of that morning wondering the streets of Lyon!

Since the 1990s, there had been an ever-increasing number of asylum seekers, economic migrants and refugees arriving at the Port of Dover. In August 2002, five men, trying to paddle their way to Britain in an 8-foot boat, were picked up in the Channel by the Dover lifeboat. They were all suffering from hypothermia. That was the fourth time that year the City of London II had under taken such a rescue. Those who made/make the crossing often failed to gain the required permission to stay but before they were sent back, disappear. Others, who made/make the crossing disappear on arrival. In 2002, on the orders of the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett, immigration officers were going into ethnic minority areas to seek out immigrants to send back. On 20 August that year, one such person threw himself overboard from the ferry and tried to swim back to Dover. He was unconscious when the Dover lifeboat picked him up and died before the City of London II reached port. Picking up would be immigrants in trouble in the Channel is still a regular occurrence for the lifeboat at Dover.

Just after the schools broke up for the summer holidays in July 2002, Britain enjoyed a heat wave with several parts of Kent recording temperatures of 32ºC. Dover beach was packed with sun lovers and many of the children were paddling around the harbour in rubber dinghies – often not wearing a life jacket. On 28 July, Dover lifeboat were called out 12 times to rescue children who had been blown out to sea, luckily all were brought back safely. Later that year Dover lifeboat crew featured in the ITV documentary series, ‘Lifeboats‘, when this problem and other types of rescues were recounted.

In February 2008, former Coxswain (1998-2003), Dave Pascall of Chaucer Crescent, died suddenly. On his retirement as coxswain, he had stayed with the RNLI becoming a training assessor visiting lifeboat stations across the country. That year also saw the death of another Dover RNLI stalwart, Roy Pain. He had devoted many years to the administration side of running the Dover lifeboat, for a long time as treasurer and then as both chairman and treasurer. Although saddened by both deaths in such quick succession, moral stayed buoyant and Dover lifeboat crew was featured on TV’s Channel 5. In 2012, in recognition for their work, many of Dover’s lifeboat crew, all of those who had served for five years or more, received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee medals.

Except for the station mechanic who is full time, the coxswain and crewmembers are all volunteers. It costs about £450,000 a year to finance the Dover station, which includes depreciation and repairs of the boathouse and the craft – at the time of writing there is talk of a move as Dover Western Docks are to be redeveloped. The Dover Lifeboat team work in conjunction with the Coastguards (Maritime and Coastguard Agency) – their station is on Langdon Cliffs, the Coastguard helicopter based at Lee-on-Solent, French and Belgium helicopters, as well as the RAF’s Air-Sea Rescue.

Finally, folk ask why the maroons are no longer fired – this is due to the advent of paging technology superseding the need and people complaining about the debris created by the maroon casings.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 21 & 28 October & 25 November 2010

Dover Lifeboat Website: http://www.doverlifeboats.co.uk