Before Dover had its first lifeboat in 1837, working vessels such as hovellers or luggers, manned by concerned locals, would go to the assistance of vessels in distress. According to a report presented to the House of Commons, between 1833 and 1835, off Dover, 1,573 vessels were reported stranded or wrecked, 129 missing or lost, while the entire crews of 81 vessels were reported to have drowned. The total number of persons drowned during those 3 years was 1,714.

In response, the Dover Humane Society was set up and commissioned a local shipbuilder, Messr. Elvin, to make a self-righting boat. Manned by volunteers, mainly fishermen, and kept near North’s Battery – close to the present day Granville Gardens – she was 37 foot (11.28 metres) x 7 foot 9 inches (2.36 metres) wide. The boat was launched by a combination of horse, women and manpower. At sea, sails were used whenever possible but more often than not, she was rowed by 12 oarsmen. Her coxswain was John Town and she was in service for 16 years from 1837 to 1853.

The next lifeboat to come on station was built by T C Clarkson in London and arrived in 1853. She was a 28 foot (8.54 metres) x 6 foot (1.82 metres) self-righter, manned by six oars and had undergone trials on the Thames, at Woolwich, where the Dover Humane Society had seen her and were impressed. Coxswain Richard White was appointed in charge of the station in 1847 but in April 1855, the Dover Humane Society invited the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), to take over its running.

Founded in 1824 by Colonel Sir William Hillary, the RNLI ruling was that all lifeboats should have the strength to withstand heavy seas and rough handling, power to free herself rapidly from water taken inboard and buoyancy to keep afloat even when flooded. Called the Peake design, the Dover lifeboat was adapted to meet these specifications.

The Dover Humane Society boat was withdrawn in 1857, sold, and the RNLI provided Dover’s next lifeboat. She was a 28 foot (8.54 metres) x 6 foot (1.82 metres) self-righter built by Forrestt of Limehouse Basin, London who specialised in building boats for the RNLI. Pulled by six oars she was in service for 6 years until 1864, though it appears she was only used once. Indeed, in December 1862 the lifeboat from Ramsgate came to the rescue of four seamen in trouble off Dover because the Dover lifeboat was not available.

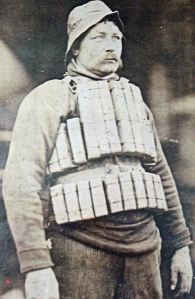

The RNLI replaced the lifeboat in 1864 with Dover’s first named boat, the Royal Wiltshire. She was paid for out of a collection organised by a Captain Reed in Wiltshire. The Royal Wiltshire was 32 foot (9.75metres) x 7 foot 5 inch (2.26 metres), a ten oared self-righter built by Forrestt. During her 14 years, she made 22 rescues with Coxswain White in command until 1870. By this time the lifeboat men would be wearing the tradional garb associated with them, clad in oilskins, sou’-westers and life belts within which the cork gave buoyancy.

At the west end of the Esplanade on the Sea Front, in 1866, a purpose built lifeboat house was erected at a cost £244. The Clock Tower was built nearby and the clocks installed in 1877. Before completion of the latter, a rocket launcher was placed on the roof from where two red rockets or maroons, as they are called, were released to summon the lifeboat crew when they were needed. At that time a ship at sea tended to only fire distress flares if it was in danger of sinking. In the case of a man overboard there was a definite procedure that all seamen on sailing ships were expected to follow.

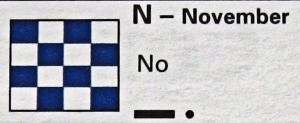

Code Flag N – with general interpretation – but also used in the olden days to indicate that the beleagured person was to the left of the ships boat sent out to rescue them.

Initially, the helm was put down and the hands would shorten sail. If the beleaguered person(s) could be seen, a life buoy would be thrown to them and hauled in. The ship’s boat would be launched to look for the beleaguered mariner(s) who could not be seen and a sailor would be assigned to climb the mizzen rigging. His job was to look out for and once spotted keep watch on the beleaguered person(s) so that he could instruct the boat crew where to go. This he would do using signal flags – M for starboard (right) and N for port (left) – and would dip the appropriate flag.

If a lifebuoy was thrown to the beleaguered person, in those days they were designed for the person to stand on the lowest step that would keep the head above the water and to hold on to handles on each side. However, the temptation was to stand on a step high enough to be able to wave at the rescuers and that often cause the buoy to capsize with subsequent loss of life.

After twenty-three years, Coxswain White of Dover lifeboat retired in 1870 and James Woodgate took the helm. In May 1875, the Royal Wiltshire was part of the flotilla that accompanied Captain Paul Boyton’s (1848-1924), second and successful, attempt to swim the Channel in his special life-saving dress. Boyton was involved in the US Life Saving Service and had crossed from Boulogne to Fan Bay, east of Dover, taking 23½ hours wearing his novel airtight suit and using a paddle. The suit was made of vulcanised rubber and consisted of a jacket with a hood and attached pantaloons within which were air pockets and pipes that enabled Boyton to inflate the suit rapidly. The suit was a forerunner of the divers’ wet suit.

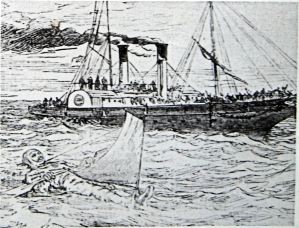

However, in March 1876, Coxswain Woodgate and the Dover lifeboat crew were in trouble. On 17 February, the steamer Strathclyde was run down by the Hamburg liner Franconia with the loss of 38 lives. The Strathclyde was about two miles east of the Admiralty Pier and on board were 25 passengers and 47 crew. The Franconia struck the Strathclyde between the funnel and the main mast cutting through her decks to a depth of four feet. The Franconia went astern to release herself but was drawn back and hit the Strathclyde again causing further damage. The Franconia managed to get free but the Strathclyde sank stern first, taking five to ten minutes. The captain of Franconia did not attempt to launch a rescue bid. The Early Morn a Deal lugger was not far away and it was her crew that rescued the survivors.

James Woodgate Dover Lifeboat Coxswain 1870-1894. He and his crew were completely exonerated of that allegation of procrastination when going to Strathclyde in 1876. Dover RNLI. AS 2010

At the inquest, it was said that although she eventually arrived the Dover lifeboat had deliberately delayed going to the rescue. This was because the RNLI paid a reward to the crews for every call answered whether the rescue was successful or not. This allegation led to an inquiry but evidence showed that the Royal Wiltshire was launched as quickly as possible after the first alarm was given. That a tug had towed the boat as fast as possible and had reached the Strathclyde in reasonable time taking into account the state of the tide, sea and weather. Coxswain Woodgate and his crew were completely exonerated of the allegations levied upon them. However, at the Old Bailey, the captain of the Franconia was found guilty of manslaughter but this was quashed on appeal. The owners of the Strathclyde subsequently brought action in the Admiralty Court against the Franconia and were awarded £45,000.

In April 1876, the Royal Wiltshire’s crew assisted the fishing boat Edith of Lowestoft and her crew of ten men. She had run aground on the Mole Rock, just outside the entrance to Dover harbour, at that time, during an easterly gale and heavy seas. For this, the Dover lifeboat crew was commended but little media attention was paid to their act of bravery. This was typical at that time. If lifeboat crews were found at fault they were savaged by the local and national newspapers, as had happened in the case of the Dover lifeboat crew and the Strathclyde. When crews put their lives at risk to save others, the media were not interested. To try and counter this, the RNLI introduced a series of awards for meritorious service and badgered the national newspapers to publish their presentation.

The 35 foot (10.67 metres) x 9 foot (2.74 metres) self-righter Henry William Pickersgill, named after the lifeboat’s patron and built by Woolfe and Sons of Shadwell, London, came into service in 1878. Her first reported rescue took place on 9 December 1881 in a south-westerly gale, when the Jersey barque Chin Chin ran aground near the South Foreland – the easterly tip of south east Kent. The lifeboat crew were a man short and Major Henry Scott, the then chairman of the Dover RNLI, volunteered as an oarsman. The Henry William Pickersgill was launched and headed through the exceptionally heavy seas and when she arrived at the scene, there was wreckage all around the Chin Chin. The lifeboat crew managed to manoeuvre alongside and rescued five men. For the rescue, Major Scott was awarded the RNLI Silver Medal, the first of many such awards to the Dover lifeboat crew.

After ten years and making five rescues, the Henry William Pickersgill was replaced in 1888. The new lifeboat was the Lewis Morice, ON197, 37 foot (11.28 metres) x 8 foot (2.4 metres) pulled twelve oars and cost £556. Autumnal gales in 1891 were particularly fierce but when the Government dredger No18, being towed by the tug Seahorse, left Sheerness for Portsmouth, it augured well that they would make the journey successfully. Unfortunately, as they rounded the South Foreland they ran into a southwesterly squall and the hawser parted. The dredger was under the charge of gunner George Barrett and the tug was unable to get near.

In answer to the distress flares released by Gunner Barrett, the Lewis Morice, towed by the Dover Harbour Board (DHB) tug Lady Vita, put to sea. Between them they managed to get the crew safely off the dredger, which sank shortly afterwards. Because of the wind, both the lifeboat and tug made for Ramsgate rather than Dover, where they landed the crew. James Woodgate was awarded a bar to an earlier awarded silver medal for this rescue.

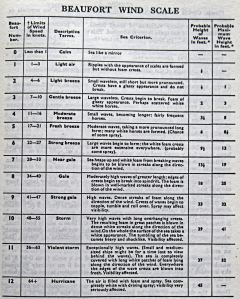

The Benvenue, 2,300 tons and laden with general cargo left London bound for Sydney, Australia. The date was 11 November 1891 and not only was it cold but as they reached the open sea a force 9 on the Beaufort scale was blowing. This meant that it was a strong gale and it drove the ship down the Channel. At 07.30hrs, she came to rest on a sandbank off Sandgate, Folkestone and started to break up. Her crew of 20 clambered as high as they could and Sandgate lifeboat went to the rescue. Using rockets, they eventually managed to get a line on board but this broke when it was hauled in.

Members of the Folkestone garrison then used field-guns to try to send a line but the line broke on discharge. By this time the wind speed had increased to storm force 10 and the Sandgate lifeboat, standing by, capsized but her crew managed to get ashore. By this time the Benvenue crew were numb with cold, exhausted and at least one was seen dropping into the sea. He tried to swim but disappeared under the waves. The Hythe lifeboat went to the disaster area but the wind had increased to violent storm 11 and she was swamped and lost. One of the crew did not manage to get ashore.

A telegram was sent to Dover asking for help and the Lewis Morice, with Coxswain Woodgate and his crew on board set out under tow by the Lady Vita. Hurricane force 12 was recorded when they reached the end of the Admiralty Pier and turned west towards Sandgate. For four hours the lifeboat and the Lady Vita battled against the wind and tide but made little headway so returned to harbour. Once ashore four men from the Lewis Morice had to be carried off. With replacement and additional crew, the Lewis Morice tried again to leave for the scene of the disaster, this time towed by the DHB steam tug Granville with the Lady Vita behind. They eventually arrived at the disaster site at about 19.00hrs and rescued the remaining crew of the Benvenue, taking them to Folkestone. It was later confirmed that the captain and four men of the Benvenue, drowned that day.

Although the Dover lifeboat men showed great courage and the RNLI endorsed this, the popular reaction was negative, saying that the Dover lifeboat crew lacked courage and had deliberately delayed leaving the port. Angry, Dover’s Mayor, William Crundall, wrote to the Times giving a graphic account of the danger the Dover lifeboat men had put themselves in and finished by saying, “I write that my brave fellow-townsmen may have credit due to them, and the public may have the pleasure of feeling that, in this awful conjuncture, the crew of the Benvenue were … saved.” (Times: 14.11.1891)

The effect was phenomenal such that three days later, Mayor Crundall wrote again to the Times saying, ‘I have received from different parts of the country several sums in recognition of the heroic conduct of the crew … I intend therefore to open a special fund for the benefit of the Dover Lifeboat crew, and I shall be happy to appropriate any further subscriptions …’ (Times: 17.11.1891)

£195 was collected and at a public meeting held in the Connaught Hall in the then town hall, on 10 December, the crews of the Dover lifeboat and the DHB tugs Lady Vita and Granville were each presented with a sum of money from the fund. At the same time, Coxswain Woodgate was presented with the RNLI diploma and Silver Medal for his general gallant service. On the following day, Captain Woodgate and his crew were involved in another rescue during heavy weather. The Lewis Morice was launched and with the help of the DHB tug Granville, went to the rescue of a French three masted schooner. That night 130 vessels were anchored in the Downs for shelter, including 15 steamers.

On the 30 December 1891, the Lewis Morice was launched at 21.00hrs to go to the help of the barque Warwickshire, an iron vessel of 692-tons and registered in Liverpool. She had left London with a general cargo and 15 hands to go to Mauritius but during a gale ran ashore at West Bay, Dungeness. There the Winchelsea lifeboat attended her. With the captain, crew plus men on board from Dungeness to work the pumps, the ship was re-floated and was being towed by a DHB and a Rye tug to Dover when another squall blew up. The towing ropes broke and the Warwickshire drifted to the South Foreland, where she was lying at anchor. Although the seas were very rough, the crew of the Lewis Morice successfully rescued all but one of the beleaguered Dungeness men. His name was Swanson and had fallen into the sea as he was jumped from the stricken vessel to the lifeboat. It was for this rescue for which Coxswain Woodgate received the RNLI Silver Bar.

The building of a Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour at Dover was started in 1893 and the Prince of Wales Pier was to be the eastern pier. To make room for the root of the new Pier, the Clock Tower was moved and the adjacent lifeboat house was demolished. It was replaced with a new lifeboat house that still stands today although with a different use. The following year, in 1894, after twenty-four years service, Coxswain Woodgate retired and was replaced by James Driscoll.

On the 25 September 1896, it was said the barometer fell by one inch and one tenth (37 mbar) in six hours. During the resultant storm, the lifeboat was launched and towed by a DHB tug to two vessels both in trouble off Folkestone. The crew rescued the men off both ships and brought them back to Dover. Within minutes, they were called out again to go to a vessel in trouble and again made successful rescues.

The following year, 1897, the RNLI was subject to a Parliamentary Inquiry when the Institute wanted to replace the rowing/sailing boats with steam powered ones. Evidence, from worthy stalwarts and salts, stated, on the one hand, that the lifeboats and crews were adequate for purpose and that steam vessels were not required. Others said that lifeboat crews tended to be incompetent and more interested in salvaging property than rescuing lives. One of those who gave such evidence was a Dover pilot of 38 years service. He added to his testimony that in the whole of his experience, the Dover lifeboat had only ever been launched three times to undertake rescues so could not see the sense of a steam boat!

Possibly because of what had been said at the Inquiry, lifeboats with oars stayed on station at Dover and the DHB tugs only occasionally towed them to rescues. In March 1898, a Dutch schooner, the Sorden, and a Ramsgate fishing vessel were in trouble during a gale and the Lewis Morice put off from the beach. Helped by men and women on the Promenade Pier pulling a guy rope she reached the pier head. From there the lifeboat crew rowed her to the casualties but was unable to reach either vessel due to the force of the waves. Eventually, a DHB tug managed to get a rope on board the fishing vessel and towed her into port. The lifeboat stayed by the schooner until the tug returned and towed her into port. The tug, the Cambria, then came back for lifeboat and towed her into port, against, it was said, instructions to the contrary.

Gales and heavy seas in January 1899 threatened to swamp the collier brig James Simpson off Dover and a French chasse-marce 71, belonging to Calais. The Lewis Morice was launched along with two DHB tugs and both vessels were brought safely into Dover. In 1895 the start was made on the proposed Harbour of Refuge to an upgrade that resulted in the Admiralty Harbour that we see today. January 1900 saw the Lewis Morice going to the help of the Admiralty Works lightship involved in the construction of the new harbour. The lightship had been hit during heavy weather by a transatlantic liner of 6,000 tons belonging to Torreys and Field. The lightship stayed afloat and the crew remained on board to undertake repairs but the lifeboat stayed on hand for 12 hours in case help was needed. The following year, 1901, the Lewis Morice was taken out of service. During her career, she was launched 17 times saving 31 lives. That year, James Driscoll retired as coxswain and William Cole took over.

William Cole was only in charge for a year when Herbert Pilcher took command until 1906. During 1901, the Mary Hamer Hoyle, ON461, replaced the Lewis Morice. She was a gift of former MP, owner of cotton mills and philanthropist, Isaac Hoyle (1828-1911) to the RNLI in memory of his second wife. Self-righting, she was the same length as the Lewis Morice and propelled by 12 oarsmen. Not long after the Mary Hamer Hoyle arrived she was out on a rescue mission. A fierce gale was blowing from the south-south-west on the 12 November 1901 and the steamer, the Stelvie of South Shields, was wrecked in Dover bay. In her death throes, she crashed into the Jasper, a large Admiralty work tug. The Jasper broke loose with men on board and headed towards the South Foreland where she came to rest. The DHB tug Granville, towed the Dover lifeboat out to rescue the crew of the Jasper but the lifeboat was unable to get close enough to take the men off.

The coastguards scaled 300-feet down the cliff and offered to take the men that way using a breeches buoy, but they refused to leave the boat. If the men had not refused, the coastguards would have fired a communication line over the Jasper and then secured a larger line to the communication line with a breeches buoy attached. The buoy is so called as it has legs in which the rescued person puts theirs so that the buoy does not capsize. However, the crew of the Jasper had refused but when the tide receded they climbed on board the lifeboat and were brought to Dover.

As the lifeboat returned to Dover and entered the Bay the wind shifted to due south and the lifeboat crew saw what look like distress flares coming from the end of the Promenade Pier. The seafront was packed with people and at first, they thought that some sort of celebration was going on. They left the rescued Jasper crew in the care of the Seaman’s Mission and went to investigate. Quickly, it was realised, a large steamer had hit the Pier and was in trouble. Soldiers from the barracks were in control of the situation and signalled for the lifeboat to manoeuvre to the lee of the vessel. Once there, several of the Dover lifeboat crew went on board to render assistance. Lines, fired by the soldiers, secured the vessel to two Dover tugs and the crew, except for the captain, climbed into the lifeboat and they too were taken to the Seaman’s Mission.

The London 2,900-ton steamer Brator hit another lightship marking the Admiralty Pier works in the early hours of 10 May 1902. The captain and three of the lightship’s crew were seriously hurt and were taken off by the lifeboat to the Seaman’s Mission, where they received attention. Throughout the building of the Admiralty harbour there were problems with vessels hitting lightships although the first one to get into trouble had actually foundered in a gale. On that occasion the crew were rescued by lifeboat. A larger lightship replaced her and she was hit by the Atlantic liner mentioned above. The next one, much larger but she too was hit, as was her successor. The one hit by the Brator was the fifth and on each occasion the Dover lifeboat went to the rescue.

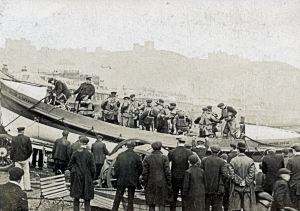

The wind had turned into a gale in the latter part of the afternoon of 10 September 1903. By late evening the staging for the Southern breakwater, then in the process of being built, was carried away. The maroons were fired – a hopper barge was adrift with two men on board. Coxswain Pilcher with the help of Police Inspector Thomas Nash, several constables and others including William Smith Clark, the master of Qui Vive, went to help. The lifeboat was in the new boathouse adjacent to the Clock Tower and when called upon the lifeboat was wheeled to the beach from where it was launched. The boat was being taken towards the sea when the Harbour Master, Captain John Irons, suggested that it would be safer to launch it by using a crane on the North quay. They turned the boat round but the wind caught it and it was driven onto a fence trapping Inspector Nash and Captain Clark. One of the wheels of the lifeboat carriage hit Inspector Nash and as he fell, the toe of his hard-capped boots penetrated his heart. The Inspector was killed instantly. Captain Clark lost a finger and the rest of his hand was badly crushed. After the tragedy it was decided to keep the lifeboat afloat at all times.

William Cole returned as Coxswain in 1906 and in 1909 was succeeded by Thomas Brockman. Under the command of Coxswain Brockman, the Mary Hamer Hoyle was launched on 6 November 1910 at 17.30hrs to help in the rescue the crew of the five masted steel-hulled sailing ship Preussen. During a gale, she had been involved in a collision off Beachy Head with the Brighton Railway Company’s mail steamer Brighton bound from Newhaven to Dieppe. The 5,081-ton Preussen, built at Geestemunde and owned by F Laeisz of Hamburg, had been bound for West Africa with a general cargo, a crew of 48 and two passengers. The Preussen had the distinction of being the largest sailing ship in the world at that time.

Following the collision the Preussen‘s master decided to ride out the gale at anchor but she broke away and was taken in tow by three tugs. While the Preussen was under tow, going up Channel, the cable parted and she went aground off Fan Bay, east of Dover harbour. The maroons were fired and the Mary Hamer Hoyle went to the beleaguered ship’s assistance towed by the tug Lady Vita. The Preussen was on the foreshore and the southwesterly wind was gale force 9.

With exceptional seamanship, the Mary Hamer Hoyle crew managed to get close to the stricken vessel but the ships crew refused to leave. Two hours later, they showed the green light, which indicated that all was well and the lifeboat was towed back to Dover. Coxswain Brockman reported that the Preussen lay well under the cliff and her topmasts had gone just before they reached her. He also reported that they had encounted a terrific sea that had ‘lifted and tossed the craft like a cork.’

The coastguards from both East Cliff and St Margaret’s Bay endeavoured to rescue the crew of the Preussen with the aid of rocket apparatus to throw ropes to the stricken ship in order to use breeches buoys, but to no avail. At 23.00hrs, the crew of the Preussen let off distress rockets and the Mary Hamer Hoyle was again launched. The wind had increased to storm force 10 giving high waves with long over hanging crests and poor visibility. Mary Hamer Hoyle was unable to get close to the Preussen and so stood off and hove to. Several hours past and eventually the Mary Hamer Hoyle did manage to get close, but the crew of the Preussen again refused to leave and at 05.00hrs, the lifeboat was towed back to Dover.

Before 09.00hrs, the lifeboat had been towed back to the Preussen by which time the Mary Hamer Hoyle arrived for the third time, the crew and passengers of the Preussen could be seen huddled together on the closed deck above the midships deck house. Nearby there were tugs from England, France, Belgium, Holland and Germany in attendance – 12 in all! It had been arranged that at high tide, in the afternoon, an attempt would be made to tow the ship afloat.

At high tide, even though the wind had not abated, the tugs manoeuvred in an attempt to get a hawser on board but none of the tugs could get close enough. By 14.00hrs, they gave up and all steamed back to Dover harbour. The Lady Vita towed the Mary Hamer Hoyle as close as she could to the stricken vessel as Coxswain Brockman wanted to try to row between the Preussen and the cliffs. The sea though was exceedingly heavy and running so they had to give up. Instead they offered to take the crew off using a breeches buoy but the crew refused and the rescue was abandoned. Again the coastguards attempted to use a breeches buoy and fired a communication line over the Preussen, but again those on board refused to leave.

The following day the wind had dropped and the Lady Vita towed a lighter to the wreck. Eventually 18 of the crew and the two passengers were taken off and landed at Dover, where they were taken to the Sailors’ Home. The remaining 30 crew members stayed on board and helped to salvage the cargo but after two days were forced to leave because the heavy weather had returned. The weather continued to take its toll on the Preussen and by January, she had broken in two. Nonetheless, much of her cargo had been retrieved, not all by the Preussen crew of the official salvage teams. Preussen crockery could be found in many Dover homes for decades after and along with the panels of the captain’s cabin much eventually found their way into auction houses!

The Dover lifeboat crew received just praise and donations for their action over the Preussen and in December 1911, they made national headlines again. This time they were successful in rescuing 18 of the crew from the stricken Norwegian barque Gudrun that was stranded on the Goodwins. By 1914 and the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) the Mary Hamer Hoyle had made 39 rescues but as members of the crew left to join the armed services the lifeboat service in Dover ceased operating.

The station closed for the duration of World War I, opening again in 1919 with Coxswain Brockman still in charge. Shortly after John Walker took over and the James Stevens No 3 came on station. A steam-driven, screw propelled boat she was 56 foot 6 inches (17.2 metres) in length and 14 foot 8 inches (4.47 metres) in breadth drawing 3 foot 6 inches (1.07 metres) with twin funnels side by side. The James Stevens No 3 was first launched in 1899 serving at Grimsby, Gorleston and Milford Avon before she came to Dover. Unlike her predecessors in Dover, that had been rowing boats, she could not be brought ashore and so was berthed in the Camber in the Eastern Dockyard.

The station closed again in 1922, the James Stevens No 3 having been launched five times during her three years service. The town’s folk were saddened and a concert was organised in aid of the Dover lifeboat that was to be held in the Connaught Hall. The venue was booked, local musicians and actors had rehearsed and all the tickets sold. The evening came but when folks turned up they found the doors locked. The organisers had not actually booked the hall, instead they had absconded with the ticket money!

A lifeboat came into service in January 1929 with Coxswain Adams in charge, moored in the Camber and was probably the William Myatt. She was reported as going to the help of the cross Channel ferry, the Ville de Liege on 11 February 1929. The month before the RNLI had announced that they had ordered a new type of lifeboat from Thornycroft at Platt’s Eyot, Hampton-on-Thames. This boat was designed to assist aeroplanes that had been forced down in the Channel and also cross Channel steamer traffic; therefore, with a speed of 17-18 knots, she would be faster than the ordinary types of lifeboats. By the end of the year the new lifeboat, the Sir William Hillary, was on station. Her career and the story of Dover lifeboat up to the present day can be read in Lifeboat Part II.

- Published Dover Mercury:

- 29 September, 7 October & 14 October 2010