By the late 1920’s all that remained of the former World War I (1914-1918) Swingate aerodrome, east of Dover, were empty hangars. (see: Marconi, Wireless & Swingate Aerodrome) Since the War, the Regular and Territorial (TA) armies had used the site, which belonged to the military, for training camps. The hangars were used for teaching purposes. At the time, Air Vice-Marshall Sir Sefton Branker (1877-1930), supported by the Secretary of State for Air – Christopher Birdwood Thomson, 1st Baron Thomson (1875-1930), was putting forward the argument that the former Swingate aerodrome be taken over by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and upgraded to a military airfield.

On 13 August 1929, Sir Alan Cobham (1894-1973) of National Flying Services Limited, had flown into Swingate where he was met by the Mayor of Dover Alderman Hilton Ernest Russell, the Corporation and senior Army and RAF officials. Discussions took place over the possibility of turning Swingate into a municipal aerodrome. The council declined to pursue the idea but the RAF officers were keen. While the Army preferred to retain Swingate as a training area. Albeit, an increasing number of privately owned aircraft were using Swingate as a stop over, particularly in bad weather.

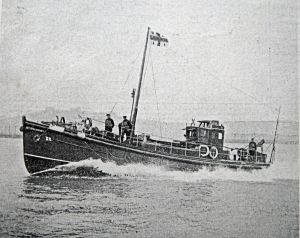

Sir William Hillary Lifeboat stationed at Dover to rescue the increasing number of aviators ditching in the Channel

With increased interest in flying and the numbers of light aircraft, the number of planes ditching in the Channel were increasing. resulting from this, the Royal National Lifeboat Institute (RNLI), in 1929, ordered a special lifeboat to be based in Dover. Named Sir William Hillary after the founder of the RNLI, she was launched on 22 November 1929 and came on station before the end of the year. The official launch took place on 10 July 1930 by Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) from the slipway in the Wellington Dock. He had flown into Swingate especially for the occasion!

The practical application of Wireless communication had successfully been demonstrated by Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) in the late 1890s. Electrical engineer and physicist, Professor John Ambrose Fleming (1849-1945), who acted as consultant to Marconi, recognised that receiving equipment was limited due to the detectors lacking sensitivity. Although crystal detectors, known as ‘cats’ whiskers’, had been invented and were proving popular, in 1904 Fleming invented the oscillation valve, as he called it. This, a thermionic valve, acted in the same way as a pump and made radiotelephony possible. The thermionic valve, or electron tube as the American physicist Lee De Forest (1873-1961) who developed the concept called it, receives, amplifies and transmits radio signals.

By the 1920s, crystal detectors were the norm and engineers and scientists were of the opinion that the curvature of the earth and the altitude of mountains determined the maximum distance between wireless stations. Ordinarily, they suggested, relay stations should be 50 miles apart but in certain cases intervals of over 100 miles could directly be bridged. Marconi suggested that very short waves, micro-waves, could overcome these limitations but this was met by scepticism. Using thermionic valves and short wave radio, in 1924, Marconi succeeded in telephoning Australia and showed that the size of the transmitters and the power needed to send signals greater distances dropped enormously. In that year he was given a contract by the British Post Office to set up circuits with Canada, Australia, South Africa and India – giving rise to the Post Office beam wireless service.

However, it was a subsidiary of the American International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation, the British Standard Telephones and Cables, that commercially exploited the thermionic valve, or valve as it is usually known, and micro-wave transmission. In the spring of 1931, they gave a demonstration of telephony across the Strait of Dover, from Leathercote Point, at the east side of St Margaret’s Bay, using a short wavelength of 18 centimetres with a power of 0.5watt. Identical equipment was placed at Cap Blanc Nez using aerials about 2.5 centemeters long within a parabolic reflector three metres in diameter. It was reported that the quality of speech transmitted was better than that of a normal telephone conversation of that time and no fading was detected.

In November 1932, the Air Ministry ordered micro-wave equipment from Standard Telephones and Cables Ltd, operating on the lower wavelength of approximately 15 centimetres. The micro-waves, oscillating at about 2,000million times a second (2000 Mhz) were generated in a ‘Micro-Radion tube’ and led to a transmitting aerial where they were concentrated by mirrors into ‘fine pencil rays’ and ‘thrown into space’ by a circular reflector some 10-feet (3.05metres) in diameter. The equipment was located at Lympne aerodrome and operated in conjunction with similar equipment ordered by the French Air Ministry at St Inglevert aerodrome south-west of Calais. In conjunction with teleprinters, the apparatus was mainly to be used to announce the arrival and departure of aeroplanes not fitted with a radio and for routine service messages.

Long before World War I, Christian Huelsmeyer (1881-1957) in 1904 had discovered range finding by transmitting very short-wave radio signals. When the signals hit solid objects they sent back their reflections or ‘echoes’ and he demonstrated his discovery to the German military. Huelsmeyer showed them that objects such as warships could be detected at a range of 1mile (1.6kilometres) but the German military were not impressed. Marconi, on the other hand, recognised the possibilities of Huelsmeyer’s discovery and gave a demonstration in 1922. Following which the discovery was taken up by a number of research establishments including the American International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation laboratories, US Naval Research laboratory and the British Meteorological Office.

Also in 1932, the US Naval Research laboratory announced that they could detect aircraft 50 miles away using micro-waves and in Britain, scientist (later Sir) Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, (1892-1973) described a technique that he called RAdio Detection And Ranging or RADAR to the British Air Ministry. As noted in the story, Marconi, Wireless and Swingate Aerodrome, thunderstorms were ill omens to the flimsy aircraft in World War I. At that time the head of the Meteorological Office in Hampshire, Charles Cave, was looking into ways of detecting thunderstorms. When Watson-Watt joined the Meteorological Office in 1915, he was given the job of finding a method of detecting thunderstorms. Watson-Watt observed that when a lightning bolt is triggered it ionises the surrounding air and gives off a signal – the crackling noise that can be heard on Medium/Long wave AM radio. With the help of his assistant, J F Herd, by 1923 they had constructed a low-sensitivity radio direction finder and by using three radiotelegraph receivers for triangulation, they could track the direction of an incoming storm.

Watson-Watt improved on the equipment and using the Admiralty’s radiotelegraph stations to locate thunderstorms went on to successfully refine the detector. This he did by using the newly invented cathode ray oscilloscope that displays, at that time in two dimensions, varying signal voltages as a function of time. While demonstrating the use of the oscilloscope in detecting thunderstorms, Watson-Watt noted that when aircraft flew by, they too interfered with the signals. £10,000 was made available by the Air Ministry to undertake further research and on 13 May 1935, Watson-Watt along with Arnold Wilkins (1907-1985), Edward (Taffy) Bowen (1911-1991), L H Bainbridge-Bell, Robert Hanbury Brown (1916-2002) and a small group of support scientists gave an effectual demonstration. Those attending were government officials, who held the purse strings, and representatives from all three armed services. It took place at Daventry and showed that an aeroplane caused a trace on the cathode ray oscilloscope and thus proving the principle of radar!

World War I sound mirror and what was believed to be a ‘Tucker’ 1920s Sound Mirror at Fan Bay. Both are now believed to be of the earlier type. National Trust

Dr William Sansome Tucker (1877-1955), the Director of Acoustical Research, in 1927, put forward a plan for a chain of 20-foot ‘Sound Mirrors’ along the South Coast to augment the 15-foot ones built during World War I (see: Marconi, Wireless & Swingate Aerodrome). It was believed, up until very recently (spring 2015) that a ‘Tucker’ Sound Mirror was built at Fan Bay along with another at Lydden Spout in 1928 but both fan bay mirrors are now believed to be of the earlier type. It had already been proved that Sound Mirrors were able to detect range over twenty miles on a good day and could ascertain direction. In 1933, a large 200-foot by 25-foot sound mirror was built on Romney Marsh and Tucker was developing 35-foot mobile steel mirrors that could be rotated. However, the increasing speed of aircraft meant that the planes would already be too close to be dealt with by the time they were detected. Albeit, the system that Tucker had developed for linking the Sound Mirror stations and plotting aircraft movements was of value. On abandoning his project, Tucker gave Watson-Watt and his team the data.

Watson-Watt and his team drew up plans for a system to detect aircraft using radio waves and soon after five radar stations were constructed, designated as Air Ministry Experimental Stations. One of these was at Swingate where four steel 364¼-foot (111 metres) transmitting towers were erected and to the east, four 240-foot (73 metres) wooden receiving lattice towers supporting a pair of dipoles at right angles to each other. There were also two shorter receiving towers. William Harbrow Ltd of St Mary Cray, who had erected the hangars at Swingate for Charles Rolls back in 1910, built the receiving towers using Columbian pine! The transmitting towers had large platforms at the top and halfway down and between the towers were strung, vertically aligned, long wave and short wave transmitting aerial arrays.

Swingate timber receiving tower erected by William Harbrow of St Mary Cray. William Harbrow Ltd 1936

Short waves radiated in pulses, fed from a transmitter block through to the bottom of the wire aerial arrays had an effective beam width of about 100°. The reflected waves were then received by a pair of dipole antennas, at a right angle to each other, on top of the receiving towers. Direction finder bearings were taken by the echoes that were displayed by vertical spikes on a horizontal range scale on a cathode ray tube. The range was measured by time delay of the echo. The azimuth – the horizontal direction expressed as the angular distance between the direction of a fixed point and the direction of the object – was measured by the relative strength of signals at the two receiving antennas. The elevation was by comparison to the receiver antennas closer to the ground.

The successful trials by the Air Ministry Experimental Stations led to the Chain Home System (CHS) of radar stations along the coast to give early warning of approaching enemy aircraft. At Swingate, the Royal Air Force (RAF), who were housed at Northfall Meadow, operated the new facility. Later St Margaret’s RAF camp was built on Reach Road for personnel operating both Swingate and Leathercote Point RAF stations. While Swingate was still in its experimental stage, the RAF personnel were not allowed to wear uniform, as absolute secrecy was imperative. A rumour was deliberately spread by saying that the site was to become a municipal airfield but not to tell anyone!

In 1938, a Graf Zeppelin was seen flying along the coast and it was later reported that it was trying to monitor transmissions from the five experimental CHS stations. As a precaution, it was said, the power of the low frequency transmission was increased relative to the high frequency transmission, which played havoc with the German receivers and deceived those on board as to the actual purpose of the towers.

The last TA Infantry camp at Swingate, prior to the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), was held from 15 July to 13 August 1939 with the emphasis on training in manning anti-aircraft defences. A battalion of TA Royal Engineers who specialised in mobility followed them. Their training was in harbouring, concealment, active and passive defence against air attacks. They also received special training in cutting rails, setting off camouflets (explosions designed to create artificial caverns) and bore hole charges in a nearby chalk quarry. Their time at Swingate was then extended and the Sappers dug ‘Crawl trenches’ all over the site in the hope that the enemy reconnaissance would not be able to determine its actual use. Finally, within deep dugouts, some of which were along the cliff face, supposed specimens of different types of posts were built. These included Bren-gun posts, dogleg trace, sniper’s post, bridge traverse and machine-gun posts and a platoon HQ. A Battalion HQ was also constructed with a 30-foot long cover.

By the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), Swingate was part of the up and running Chain Home System. This covered the British mainland coast from the Isle of Wight to Scotland staffed by the RAF – wearing their uniforms! Although work had been carried out on radar technology in France, Japan and Germany by the time War broke out, Britain was in the forefront. Further, Britain was the only country with airborne radar that enabled fighter aircraft to detect enemy aircraft in darkness. This had the ability to gauge the enemy’s speed and range. Britain had also developed the cavity magnetron that enabled a very narrow beam of radio waves to be transmitted, giving the precise location of approaching aircraft.

Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay – Fortress Dover Commander from 24 August 1939 to April 1942. Doyle Collection.

Air defence, in the south-east of England, was based on successive zonal layers centred on London. Early warning of approaching enemy aircraft consisted of the age-old visual observations and the Chain Home System. Small anti-aircraft gun batteries within the complex and the nearby World War I Langdon battery, west of Swingate protected the Swingate masts. This was refurbished and became a command post and a second battery. A command post was constructed to the east of and nearer Swingate at Fan Bay by February 1941. The command post-batteries, of which there were several in and around Dover, were well equipped with modern technology as it became available and had their own plotting rooms. The batteries were responsible to the Fire Command Post – part of Fortress Dover – at the Castle. Throughout the War, all of Dover’s defences, be they on land, sea or air, came under the Combined Operations Headquarters, also based at the Castle. There, all sensor data was organized, and analysed and commands given for artillery fire. Later these commands were extended to intercept fighter missions. The officer with overall responsiblity was the Fortress Commander and from 24 August 1939 to April 1942, this was Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945).

In May 1940, the French and Belgium Channel ports fell to German occupation, which led to the Dunkirk Evacuation that was masterminded by Bertram Ramsay. Information gained by the Chain Home System at Swingate played its part. Following the fall of Dunkirk, General Field Marshall Hermann Goring (1893-1946), Commander of the Luftwaffe, issued instructions for the first phase of a battle, which if successful, would establish air superiority over the Channel. This would be followed by the invasion of Britain. As a result, on 2 July 1940, attacks on shipping and Channel ports by small groups of bombers with fighter protection began. Defences around the country were quickly erected and at Swingate, miles of barbed wire were laid around the complex and pillboxes were erected. The compounds were made into strong points, with extra barbed wire, ack-ack gun emplacements and block traverses fitted with platforms in case the expected Battle of Britain, as it was called, was lost.

Fighter Command Groups and Sector Boundaries, airfields and squadrons 18 August 1940. Battle of Britain Memorial, Capel.

Swingate, as an RAF station, came directly under RAF Fighter Command and at the time there were eight military airfields in Kent, Biggin Hill, Manston, Hawkinge, Gravesend, Eastchurch, Detling, Lympne and West Malling. The first four were to play a major role in the forthcoming Battle and in overall charge was Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, Commander in Chief Fighter Command, from 1936 to 1940. Fighter Command was divided into four Fighter Groups with each group subdivided into sectors. Each sector had an operations room plus emergency standby and satellite airfields. Information was collected by the ‘Y’ service, which monitored German wireless messages along with Chain Home radar stations that tracked aircraft movements. Each sector controller was responsible for up to six squadrons and incoming raids tracked by radar were plotted in the operations room on large detailed maps using wooden blocks, called plots, marked with the raid number and estimated number of aircraft following which the appropriate squadrons were deployed.

The prolonged aerial conflict for control of the skies above the Channel and South Eastern England took place between 10 July and 31 October 1940. It was at this time that the towers at Swingate, as the nearest Chain Home station to the Continent, came into their own with the station, successfully reporting the Luftwaffe bomber formations before they had crossed the French coast. By the end of June, the Luftwaffe had lost 270 aircraft, the Royal Air Force 145, but at sea 18 steamers and 4 British destroyers had been sunk and in response, all coastal convoys were abandoned. At the German High Command, concern was being expressed that the British had found some way of early detection of their attacks and it was reported that the Chain Home masts played some part in this. Goering made a point of looking at the Swingate masts through binoculars, and it is said on the internet that he dismissed them as of little consequence. Nonetheless, on a moonlit night shortly after Swingate was bombed but little damage was reported.

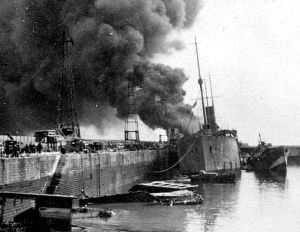

On 29 July, Swingate radar showed that there was a build-up of German formations over Pas de Calais of more than forty dive-bombers with escorting fighters heading for the port of Dover. A number of Royal Navy ships and minesweepers were berthed in the harbour. From the Castle the Fighter Command scrambled squadrons to intercept and both anti-aircraft guns and Royal Navy ships’ guns started firing. In the sky above Hurricanes, Spitfires, Messerschmitts fought while those dive-bombers that made it, dropped their loads on the town and harbour and the 10,000-ton depot ship, Sandhurst was hit. Laden with ammunition and torpedoes, Dover tugboat and firemen using thousands of gallons of seawater fought to contain a potential catastrophe. All around more bombs rained on the harbour. At the same time other bombers circled Swingate, demolishing barracks and damaging a standby transmitter. The feeder line insulation was also damaged due to pressure waves.

Temporary repairs were undertaken at Swingate and a makeshift barrack block was erected. Then, much to the disbelief and annoyance of those involved, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAFs) at the station were relocated to a base outside of Dover. The order had come from the Fortress Commander’s office and said, in essence, that all non-combatant personnel from the Dover Garrison area had to go to safer locations. It was explained to those involved that the WAAFs played a crucial role in the interpretation of the radar signals but to no avail even though WRNS (Women of the Royal Naval Services) worked at the Castle!

Sometime during the summer of 1940, the Windmill at St Margaret’s Bay was commandeered under the orders of Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay. It was painted shiny white and taken over by a special unit of the WRNS, all of which were German linguists. As part of the Admiralty Lookout team, their job was to monitor the radio messages from E-boats – fast, wooden hulled motor boats that attacked Allied shipping in the Channel – and report them to the Fortress Command. When the offensive was taken in 1941, these WRNS, along with naval personnel, operated transmitters that jammed the E-boats’ communications and radar.

On Monday 12 August, the town and harbour came in for another major onslaught, this time from cross-Channel shelling. Overhead, dive-bombers approached and Swingate was targeted. Feeder cables were severed and temporary repairs were made. Two days later, Swingate picked up a massive enemy aircraft formation over the Pas de Calais and four fighter squadrons were sent out. Over 200 aircraft battled it out in the skies above Dover causing a tremendous amount of damage but with few civilian casualties and those were minor. At sea, the unarmed South Goodwin Lightship, that under its previous name of South Sands Lightship had played an important part in the development of radio, was lost. Albeit, only two Hurricanes were hit while four dive-bombers and four Messerschmitts were brought down. Those at the Castle realised the full importance of Swingate.

Along with a number of other Chain Home stations, Swingate came under a heavy attack from dive-bombers again, on Monday 12 August. Feeder cables, telegraph poles and an operation hut was destroyed taking the main transmitter off-air. Some twenty minutes later, a standby unit became operational and 97 minutes after the attack, the main transmitter was back on-air. A week later on the afternoon of 19 August, sixty enemy aircraft were detected by Swingate radar flying at about 20,000-feet between Dungeness and North Foreland and going east. Suddenly two bombers peeled away dropping their load on Swingate, Northfall Meadow, Castle and Castlemount. Although no civilian casualties were reported, the same could not be said for the military of which there were many. The towers at Swingate, again, survived but not the cables.

Five days later, the Swingate cables having been repaired, the station reported that there was another build-up of German formations over Pas de Calais and they were met by RAF fighters and anti-aircraft guns. Swingate was again attacked and the attacks continued throughout the Battle of Britain. Towards the end, the towers came under attack from long-range German guns but survived. By 31 October 1940, against the heaviest of odds, the British forces compelled the Germans to abandoned their proposed invasion.

Following the Battle of Britain, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay extended the facilities at Swingate to help Naval plotting by tracking both enemy and friendly coastal forces. RAF Swingate quickly proved its worth in this field, enabling Dover based Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) to make a succession of successful interceptions. However, the German High Command having recognised that the Swingate Towers had played an important role in the Battle of Britain the station was bombed several times from the end of October and in November 1940. One of bombs made a direct hit on a switch room and the place was totally wrecked. It was said that none of the airmen inside were killed or injured – but stating that no one was killed or injured was often the case in relation to armed service personnel during the War. Standby equipment at Swingate was used for some time after, as it took several months to make full repairs.

In the afternoon of Thursday 14 November, the towers came under a concerted attack from bombers. The formation had been detected and followed across the Channel, so the anti-aircraft batteries were ready. It was probably a combination of surprise that the batteries were ready and the magnitude of their barrage that caused the bombers to change direction. However, they did drop their load but missed the towers. The result was death, injuries in the town of Dover and destruction of the RAF’s station’s unofficial vegetable patch! A few days later, the bombers returned dropping some 20 bombs on the station. The sick quarters and the Officers’ Mess were severely damaged but no one was reported killed or injured and the radar installations survived intact.

From February 1941, the gun batteries along the coast were equipped with radar. This made their task more effective as their job was to stop enemy ships going through the Dover Strait. It was a sunny clear spring day on 29 April that year, when the German long range guns across the Channel turned their sights on Swingate and fired airburst shells. The number of personal injured or killed and the damage done to the radar station is unknown but it is on public record that three locals, Dennis Keeler, William Irving and James Rogers, who worked there, were injured. All through the War, farmers kept sheep at Swingate fields and every morning they checked them and took away the dead ones killed during attacks. However, it was said that injured sheep would hobble to the RAF camp at St Margaret’s, find their way into the kitchens of the camp, where they would sheer themselves of their fleece and find their way into the cooking pots!

During the first part of the War, the German Battle Cruiser Scharnhorst operated unchallenged in the Atlantic resulting in the sinking of 115,622 tons of British Merchant Shipping. Early in 1942, along with her sister ship, Gneisenau and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, she was in Brest, Brittany – northwest France. It was known that following refit they were going to Norway and intelligence suggested that they would make the attempt to leave Brest at night. An allied submarine was detailed to watch Brest harbour and during the early evening of 11 February 1942, the submarine went out to sea to recharge her batteries. The three ships escorted by six destroyers and ten torpedo boats, used the opportunity and slipped out of Brest harbour undetected.

As the night wore on what had been sea mists turned into thick fog aiding their escape. Then Messerschmitt fighters flew in to protect the convoy, which was first picked up by radar at the Rye Chain Home station, east of Hastings. The officers in charge deemed the report as unreliable as it was believed that the ships were still in Brest. However, two RAF reconnaissance flights were sent to investigate. The guarding E-boats supplemented the fog by putting up a smokescreen but the reconnaissance planes were able to verify the Rye report. By that time other Chain Home stations, including Swingate, had picked up the convoy. More planes left their bases and soon engaged in combat but were outnumbered and returned to base.

By 11.45hrs, the convoy were passing Boulogne and entering the Strait of Dover. Five Motor Torpedo boats left the port but were unable to penetrate the fog and smoke screen, so returned to base. The German convoy then came under attack from the heavy guns of South Foreland Battery, where radar location was used, but after 15 minutes the convoy was out of range. The German convoy continued to come under attack from both sea and air as they passed through the Channel and into the North Sea with the Gneisenau retaliating and hitting the Worcester with three salvoes. During the whole of this time, the RAF carried out 256 sorties to bomb the German fleet but due to the weather and smoke screen, only 40 were on target, without causing much damage and the three ships reached German waters. 106 RAF aircrew, 24 Royal Navy crew of the Worcester and 13 aircrew of the Fleet Air Arm 825 Squadron lost their lives. There is a monument on Dover’s Marine Parade to the Channel Dash or Operation Fuller, as the event was officially called.

In the subsequent Inquiry, one of the reasons given as to why the Rye report had not been taken seriously was that Chain Home stations were excellent at detecting high flying aircraft but not low level. The German’s were aware of this and low-level air attacks were increasing. On 26 April 1942, flying in low, an aircraft dropped three bombs on Betteshanger colliery, near Deal. Nine surface workers were injured, and 182 miners were trapped below until the pit winding mechanism was repaired to get them out.

To deal with such occurrences the Chain Home Low (CHL) system was developed, the nearest station to Swingate was at Fan Bay. At about the same time Swingate became part of the Gee Chain of radar stations. The Telecommunications Research Establishment, following the work of Robert J Dippy on short-range blind landings, had developed the Gee radio navigation system. This was a long-range general system that enabled aircraft to attack cities at night without the need of bombsights or any other external references and revolutionised the effectiveness of RAF bombing raids. The first plane to use the Gee Chain was a Wellington Bomber piloted by Pilot Officer Jack Foster of 115 Squadron – later a Squadron Leader who was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross. As Gee Chain surface-plotting capabilities improved Swingate’s work was extended to Air-Sea Rescue.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbour, in December 1941 by the Japanese, the US came into the War. The 127 AAA Gun Battalion were sent to Swingate, joining the Royal Regiment of Artillery in defending the station. The WAAFs returned to the station in 1943 but the shelling from across the Channel was unremitting. In the late spring of 1943 the RAF moved as much of its operations as was practical from Swingate to a new facility in the caves below the Castle. It was four levels of a tunnel complex dug within the cliffs and became known as DUMPY – ‘Deep Underground Military Position Yellow.’ The project was completed in April 1943.

The attacks on Swingate did not let up and in January 1944, there was a direct hit resulting in a considerable number of fatalities and injuries among the duty personnel. The Ops-Room was demolished and the towers were damaged. As a result, an Ops-Room was installed within the DUMPY complex. During the preparations for the D-Day Landings on 6 June 1944, the demand on Swingate escalated but so did the attacks not only from shells but also from the V1 flying bombs (doodlebugs). During this time, the American Battery earned a reputation for its ability to hit the flying bombs on the nose as soon as they were in range. Following the D-Day Landings in Normandy, the shell attacks from across the Channel became incessant, day and night. That is, until 26 September when the Allied advance captured the guns around Calais and Boulogne.

Following the War, Swingate remained a RAF station manned by Signal Units and the batteries by the Artillery. Moves were made to return the site back to its pre-war role as a TA Training ground, and in the summer of 1948, some 100,000 members of the Combined Cadet Force (CCF) were camped there. Mannie Shinwell (1884-1986), the Minister for War, was supposed to address them but gale force winds meant that the whole camp had to move to Shorncliffe, Folkestone to hear the Minister‘s speech! The following year the CCF camp returned to Swingate but tensions between the US and the USSR of the Cold War (1945-1980) were escalating. It was realised that if war resulted it would be nuclear – very different to that of World War II. At the Castle DUMPY was converted into a Regional Seat of Government and at Swingate, the batteries were stood down.

Even though the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) had inaugurated the world’s first television service on 2 November 1936, BBC television did not reach the general public of Dover until 1961 (See Television Transmission and Production). However, in 1952, using a Swingate tower and in cooperation with British Railways Southern Region, the BBC had undertaken ship to shore television experiments. This was to ascertain the possibility of obtaining television pictures on a cross-Channel ferry. The BBC were also using the tower as a temporary repeater station to beam television across the Channel to Calais and from there, using repeater stations throughout the Continent.

The conversion from the British 405 lines to the Continental 625 lines was undertaken by the receiver stations but it did mean that viewers in Paris, Rome and Berlin were able to view Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on BBC but not the locals in Dover! In 1955 one of the Swingate transmission towers was dismantled and the following year a permanent two-way cable television link was established between London, through St Margaret’s Bay, to the Continent. BBC converted their Swingate operations in 1957 to receive Continental transmissions as well as sending them. This was to enable the British viewers, who could get BBC, to see the Queen on a State visit to France and Denmark. In the meantime, the Croydon transmitter was built to broadcast the London ITV signal. After fierce competition, Southern Television won the ITV franchise for the south and southeast of England. They went on air at 17.30 on Saturday 30 August 1958 from their studios in Southampton using a Swingate tower as a relay to Dover.

The conversion from the British 405 lines to the Continental 625 lines was undertaken by the receiver stations but it did mean that viewers in Paris, Rome and Berlin were able to view Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on BBC but not the locals in Dover! In 1955 one of the Swingate transmission towers was dismantled and the following year a permanent two-way cable television link was established between London, through St Margaret’s Bay, to the Continent. BBC converted their Swingate operations in 1957 to receive Continental transmissions as well as sending them. This was to enable the British viewers, who could get BBC, to see the Queen on a State visit to France and Denmark. In the meantime, the Croydon transmitter was built to broadcast the London ITV signal. After fierce competition, Southern Television won the ITV franchise for the south and southeast of England. They went on air at 17.30 on Saturday 30 August 1958 from their studios in Southampton using a Swingate tower as a relay to Dover.

As the Cold War continued to escalate the RAF opened a radar base at the old World War II camp on Leathercote Point, near the Dover Patrol Memorial, St Margaret’s, as a nuclear attack early warning station. NATO had introduced ACE High (Allied Command Europe) early warning communication system and although Swingate was not a major site, it too was part of it. Although supposedly secret, the evidence was there for all to see from the four huge dish antennas that had been erected on the site! A network of Royal Observer Corps underground posts were established in 1962 with the job of monitoring radioactive fallout in the event of a nuclear attack. Built of reinforced concrete the complex is below ground and about 25-feet square (7.5square metres). Nuclear blast and radiation proof, it comprised of a workroom, accommodation, lavatories and washroom. It still exists and now has English Heritage Grade II Listing status.

Royal Observer Corps 1960s Nuclear Blast observer post – Dover ROC post at Swingate (1). Nick Catford

Nick Catford, whose work on Kent’s Royal Observer Corps (ROC’s) underground posts was published by Kent Defence Research Group in 1999, has sent three photographs of the Dover ROC post at Swingate. The first shows main access shaft with the ventilation shaft to the rear. The pipe on the left is for the Fixed Survey Meter (FSM) probe. When in use, the flat top was removed and replaced by a plastic dome that was bolted in place. A Geiger Muller tube was then pushed up into the dome from the monitoring room below. This was a sensing device used for the detection of ionising radiation. The level of radiation could then be read on the fixed survey meter below. The metal dome on the top of the ventilation shaft was the mounting for the Ground Zero Indicator (GZI). The GZI consists of four horizontally mounted cardinal compass point pinhole cameras within a white enamelled metal drum, each ‘camera’ contained a sheet of photosensitive paper on which were printed horizontal and vertical calibration lines delineating compass bearing and elevation above the horizon. The bright flash from a nuclear explosion would burn a mark on one or two of the papers within the drum. The position of the burn spot enabled the bearing and height of the burst to be estimated. With triangulation between neighbouring posts these readings would give an accurate height and position. A third instrument mounting for the Bomb Power Indicator (BPI) is hidden in the grass.

Royal Observer Corps 1960s remains of the inside of a Nuclear Blast observer post – Dover ROC post at Swingate. Nick Catford

The second of Nick Catford’s photographs is the internal view of the three-man 15-foot by 8-foot monitoring room. The furniture was the same in all ROC posts, twin bunks and single bed, instrument table and a cupboard for small stores, eating utensils etc. The post was not connected to the mains electricity supply. There was a 12-volt light powered by the battery that can be seen. A generator for charging that battery was kept in the sump at the bottom of the ladder. The post had a crew of four but this was later reduced to three nationally and the single bed was removed.

Royal Observer Corps 1960s Nuclear Blast observer post – Dover ROC post at Swingate (2). Nick Catford

The third photograph that Nick sent, along with the descriptions cited, is a closer view of the access shaft. Beneath the hatch there is a 15 ft fixed iron ladder. At the bottom of the shaft there are two rooms. A small room that housed an Elsan chemical toilet and storage shelves.

BBC eventually broadcast low powered TV transmissions from Swingate for the Dover viewers in February 1961. Later that year VHF (FM) radio was transmitted by attaching antennas to the middle tower of the three remaining towers. Although in 1960, the Leathercote Point RAF station closed, the radar facilities were maintained until 1982. In October 1968 the Royal Observer Corps monitoring station closed and was eventually stood down in 1991 following the end of the cold war. Only a succession of Signal Units remained at Swingate. A shorter transmitting tower was erected as an intermediate relay station to British forces stationed in West Germany.

Not long after the Royal Observer Corps moved out, the United States Air Force moved in. Initially, the USAF said that they were at Swingate to use the facilities as a communications link for their bases throughout Southern England. Adding, that to meet the regulations of the time a considerable amount of reconstruction work had to be done. As time past, doubt was expressed on this explanation. In 1969, the BBC introduced stereophonic programmes on Radio 3. One of the transmitting stations was Swingate, broadcasting on 92.4 Mhz FM.

Memorial to the the men of Nos 2, 3,4 and 5 Squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps who took off from Swingate between 13 and 15 August 1914. Erected in 1966. AS 2015

Built in early 1966, is the granite memorial we can see today on Upper Road, Swingate. The memorial commemorates the men of Nos 2, 3,4 and 5 Squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps who took off from Swingate between 13 and 15 August 1914, (see Marconi, Wireless & Swingate aerodrome). The Flying Corps had flown to Amiens to support the British Expeditionary Force at the start of World War I. The idea of the memorial came from Group Captain George Carmichael, who flew with one of the Squadrons and the memorial patron was Sir John M Salmon (1881-1968), the senior Air Marshall of the RAF. On 11 November that year Dover’s ‘Old Contemptibles’ laid a wreath of honour. Captain JW Bareham, who attended, had flown from Swingate with the original contingent.

Swingate Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) – openstreetmap thanks to Protect Kent – Branch of the CPRE

Arms control treaties had cooled the Cold War and in the spring of 1970 the RAF Signal Corps were withdrawn from Swingate. The towers were designated for television use and the last contingent, RAF 345 Signals Unit, moved out at the end of March that year. Problems with lorries backing up on the roads leading to the port of Dover, during bad weather or other reasons for ferry delays, was becoming an increasing problem. In the early 1970s the A2 bypass from the top of Lydden Hill to Eastern Docks was under consideration and following the closure of RAF Swingate, moves were made to turn the whole area into a lorry park. The bypass opened in early 1977, passing close to Swingate, but the site had been ruled out for two reasons. The Americans were still there and the site was/is a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB).

The AONB status became a local issue in 1979 when the Americans wanted to set up a temporary transmitting station for use by military aircraft in establishing long-range navigational fixes in the North Sea and Europe. At the time the ordinary folk were unaware that the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan that year was to usher in another chapter of the Cold War. Planning permission was given but reluctantly. As a reaction to the heightened international tensions, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), founded in 1958, increased their activity. In October 1981, they published a map showing places that were likely to come under attack if there was a nuclear war and two places named as being vulnerable were in Dover. One was DUMPY – the emergency Regional Seat Government and the other, the American base at Swingate!

Following the end of that chapter of the Cold War the USAF moved out of Swingate and in August 1986, a second Memorial was erected near to the RFC Memorial on Upper Road. This was in memory of all ranks of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and of the 127 AAA Gun battalion of the United States Army, who had served in the Dover area during and shortly after World War II. Over the following years, the Swingate towers were used by the fast growing telecommunications industry.

In November 2007, a local, P Chiselden, became concerned that one of the red navigation warning lights on the top of one of the three remaining towers was no longer working. He reported this to the police, the local MP of the time – Gwyn Prosser – and the local papers. Before the light was fixed, a local reporter asked a Ministry of Defence (MoD) spokesman if there were plans to demolish the towers. The spokesman responded by saying that ‘the masts were used for a variety of radio transmissions, some for the public, and others including cross-Channel communications and that the site is secured.’ It therefore came as a shock when in March 2010 one of the three towers was dismantled without notice. Another MoD spokesman said that the tower was no longer needed and that it had become unsafe. He added that none of the towers were Listed by English Heritage.

People were outraged and before long applications were made to English Heritage for the remaining structures on the site to be Listed. Today, Transmitter Tower 2 has grade 2* listing and the Transmitter site, the Royal Observer Corps Underground Nuclear Monitoring Post plus Receiver site together with a buried World War II Reserve and Pillbox all have Grade 2 Listing.

In 2014, the Langdon Cliff based National Trust with archaeologists and some 50 volunteers uncovered the two sound mirrors at Fan Bay and the nearby World War II battery below Swingate. The site is open to the public and well worth a visit if you are fit – there are a lot of steps!

- Presented: 30 January 2015