Charles Dickens (1812-1870), the famous 19th century British author, was a frequent visitor to Dover throughout his adult life. His first visit to the town was as part of an acting troupe in the 1830s, when the company played at the Apollonian Hall on Snargate Street. Dickens later crossed to and from the Continent via Dover, as he became increasingly successful, when he was on speaking tours. He also stayed in the town for several weeks at a time. Towards the end of his life, these stays became more frequent. Albeit, unlike Boulogne, Broadstairs and Folkestone, Dickens did not write a special article on Dover possibly because Dover strongly features in many of his published works. Some of these are looked at below.

Charles Dickens, a second child, was born in Portsmouth on 7 February 1812. Shortly after, his family moved to Chatham, Kent where he spent his first five years. There, Dickens father, John Dickens (1785-1851), worked as a clerk in the pay office at the Royal Navy Dockyard and the family lived at 2 Ordnance Terrace – now number 12 that can still be seen. Later used as the basis for the character Wilkins Micawber in Dickens novel, David Copperfield, John Dickens was a spendthrift who held the eternally optimistic belief that ‘something will turn up.’ Unfortunately in 1821, due to financial difficulties, the family were forced to the smaller and cheaper house in St Mary’s Place, closer to Chatham dockyard, but since demolished. During this time, on walks with his father, Dickens would pass Gad’s Hill Place at Higham near Rochester and he vouched that when he earned enough money, he would buy the house.

Advert in the Times of 21.03.1836 for Sketches by Boz published by John Macrone, St James Square, London

His father’s lack of financial acumen landed him in a debtors’ prison and the family was again forced to move, this time to Camden Town, London. There, to help support the family, Dickens worked 12hour days in a shoe polish factory. This meant that his schooling was intermittent but he did manage to gain some education and in 1827, Dickens was articled to a solicitor’s clerk. The following year he became a freelance reporter when he submitted short articles to the Monthly Magazine published between 1796 and 1843, but as with other contributors, Dickens was not paid. From 1834 Dickens secured the job of a reporter with the Morning Chronicle published from 1769 to 1862, and they began publishing Dickens short stories for which he used the pseudonym Boz.

Title page of 2nd series of Sketches by Boz by Charles Dickens illustrated by George Cruikshank US Library of Congress Prints & Photo Division

Dickens stories were brought to the attention of London publisher John Macrone, who published some in a two-volume book. This was in February 1836 and had the title Sketches by Boz. George Cruikshank (1792-1878) illustrated the stories and a second series of short stories was published in August that year. The Title page of the latter was illustrated by George Cruikshank and shows two figures, closely resembling Dickens and Cruikshank, waving from a balloon. However, even before the first volume was published, Dickens received an offer from publishers Chapman and Hall, founded in 1834, for a series of 20 monthly-related articles of 12,000 words each. They were given the title, Pickwick Papers with the first one being published in April 1836. By the time the fourth episode of the Pickwick Papers was published, the series had become immensely successful.

On 2 April that same year, Dickens married the talented, fun-loving, daughter of George Hogarth (1783-1870), the Editor of the Evening Chronicle, a successful paper published in Newcastle, which also published Dickens work. Catherine (Kate) Thomson Hogarth (1815-1879) was an established author in her own right when she first met Dickens but was soon eclipsed by her husband a situation added to by the demands of motherhood. Kate had the first of their ten children in 1837. Shortly after, the family moved to 48 Doughty Street, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 2LX – now the home of the Charles Dickens Museum. Over the next few years they moved to various localities in London, eventually buying, in 1851, the large but now demolished Tavistock Place, also in Bloomsbury. This house stayed in Dickens possession until 1861.

During his lifetime, Dickens published fifteen novels, five novellas, and countless stories and essays. His skilfully drawn characters were, for the most part, composites of several characters that he knew, were acquainted with or came from local folk-law. The settings for his works, for the most part, were drawn from real life and there is little doubt that Dover, its history and its people provided Dickens with inspiration.

While the serialisation of Pickwick Papers was still being published, Dickens became the editor of Bentley’s Miscellany for two years from 1836. Founded by publisher Richard Bentley (1794-1871) that year, the magazine was to run until 1868 when it was merged with Temple Bar Magazine. In February 1837, Dickens published The Parish Boy’s Progress or as the novel is better known, Oliver Twist in Bentley’s Miscellany and used his pen name Boz. This was followed by Nicholas Nickleby in 20 parts and concluded in November 1839. To try and earn more money, Dickens increased his output and persuaded Chapman & Hall to publish a magazine specifically for his work. Called Master Humphrey’s Clock, it ran from 4 April 1840 to 4 December 1841. During that time Dickens published several of his short stories and the novels Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge.

These were followed by a trip to the US with Kate while her younger sister, Georgina (Georgy) Hogarth (1827-1917), looked after their children. While there, Dickens published American Notes followed by the 20 part novel Martin Chuzzlewit, from January 1843 to July 1844, neither of which was well received compared to the Old Curiosity Shop. Albeit, for Christmas 1843, Dickens published A Christmas Carol, the first of his annual Christmas books. The following year, he and Kate went to Italy, which resulted in a series of articles published in the Daily News and were aptly named Pictures from Italy. Dickens had founded the Daily News but it was not a commercial success and after 17 issues, he handed the editorship over to journalist John Foster (1812-1876) who turned the newspaper around and ran it until 1870. The paper eventually became the News Chronicle, which ceased publication on 17 October 1960 on being absorbed by the Daily Mail. Dickens went to Switzerland in 1846 and during a visit to Laussane, he started the 20 part Dombey and Son, published between October 1846 and April 1848.

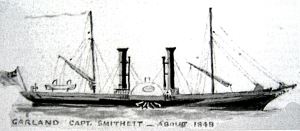

Prior to the completion of the South Eastern Railway (SER) line to Dover on 27 January 1844, travellers from London to the Continent would come to the port by mail coach or stagecoach. The mail coach would have been quicker but more expensive of the two. In 1842, SER had opened up their railway line to Folkestone and from there, passengers could take the steamship to Boulogne. Albeit, for his trip to Switzerland, it would seem that Dickens travelled to Dover by the cheaper horse drawn stagecoach and then crossed to Ostend. At the time there were two services going to Belgium out of Dover, the Dover packet Garland, a wooden paddle steamer built by Fletcher & Fearnall, London, of 295gross tonnage and engined by Messrs Penn & Son, Greenwich. The Garland had arrived at Dover on 27 May 1846, was captained by Luke Smithett (1800-1871) and on average made the crossing to Ostend in 4hours 30minutes. In 1846 the Belgium Government had started its own steam ship service between Ostend and Dover but this was not a financial success at the time that Dickens made this crossing and therefore not very reliable. So therefore, he most likely crossed on the Garland. Of interest, in October and November 1848, the Belgium Government came to an arrangement with the Admiralty with respect to their service and from then on the Company, Belgium Marine, proved to be a success. It finally ceased operating the Dover-Ostend service at the end of 1993.

David Copperfield

At this time, it would seem that Dickens frequently crossed to the Continent, mainly to escape creditors and an increasingly unhappy home life. Although Dickens was known to drive a hard bargain his increasing large family were a drain on his finances. Kate had at least twelve pregnancies and gave birth to ten children, which Dickens blamed totally on her. Increasingly, she had become the butt of his irritability over the most minor of her supposed many misdemeanours, so the household was far from content when both parents were at home. Underlying all of this were the failings on the part of Dickens to be prudent with his income. Moreover, this era was known as the ‘Hungry Forties,’ when the nation was impoverished and Dickens stagecoach journey to Dover at that time possibly played a part in the inspiration for his next novel, David Copperfield. Published in 20 parts from October 1846 to April 1848 it was illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne (1815-1882) using his pen name Phiz chosen to rhyme with Dickens pen name Boz.

There is no doubt that Dickens had collected material appertaining to Dover for his eighth novel, David Copperfield, following his visits to the town. The novel was first published in serial form from May 1849 to November 1850 and Dickens said that it was his favourite book. David, the hero of the story, is born into a comfortable middle class family but his father dies before he is born. His softhearted mother and the loyal housekeeper, Clara Peggotty – throughout the novel referred to as Peggotty – are supported by David’s formidable aunt, Betsey Trotwood who lives in Dover. However, at David’s birth, when Miss Trotwood realises that the child is a boy, she renounces him and departs.

His gentle mother and Peggotty are content until David’s mother marries again. The stepfather, Murdstone, and his cold, cruel, sister dominate the household and after the death of David’s mother, they rule so David is far from happy. The situation goes from bad to worse and after attending a grim school, David ends up in the employment of Murdstone and Grinby. While there, David lodges with the kindly Micawbers but as already noted, the character of Wilkins Micawber is based on Dickens father, John, an eternally optimistic spendthrift. Due to financial problems the Micawbers are forced to leave London and David, feeling abandoned, decides to run away. He sets off to Dover to look for his long lost aunt, Betsey Trotwood.

Igglesden’s baker’s shop in Market Square and founded in 1788, where Charles Dickens wrote, David Copperfield rested when he first arrives in Dover. Dover Museum

Having no money, David has to walk from London to Dover and eventually arrives tired, penniless and hungry. He rests by sitting on a baker’s steps in Dover’s Market Square. Immediately after publication this was identified as Igglesden’s baker’s shop and Dickens implicitly confirmed this. Of interest, John Igglesden had opened the bakery in 1788 and eventually his descendants went into partnership with the Graves family. In 1905, with the building of Lloyds Bank next door, the baker’s shop was rebuilt by Charles Edwin Beaufoy (1869-1955) in a mock Tudor style. The bakery was then expanded to include a restaurant and the business, Igglesden and Graves, remained as such until 1967. The building was then sold to John Wilkins, who had also bought properties along the adjacent Church Street for redevelopment. Before planning permission was given, Wilkins had to agree to retain the iconic façade. The premises were subsequently occupied by stationer Dennis Weaver (1931-2007) before becoming a café in 1993. At the time of writing it is in the possession of a charitable trust set up by Dover Town Council and is a café called The Market Square Kitchen that is run by a family firm.

Following his rest, David makes his way to the seashore and inquires among the boatmen after Miss Trotwood. He is told by one boatman that, ‘she lived in the Southforeland Light and had singed her whiskers by so doing so.’ South Foreland Lighthouse is along the cliffs east of Dover close to St Margaret’s Bay. Another, boatman tells David that ‘she was made fast to the great buoy outside the harbour, and could only be visited at half-tide.’ A third is adamant the Miss Trotwood is ‘locked up in Maidstone Gaol for child-stealing’ while a fourth says that ‘she was seen to mount a broom, in the last high wind, and make direct for Calais!‘ David then asks the fly drivers but they too were not helpful nor were the shopkeepers he asks. Eventually, David returns to the Market Square and starts chatting with a kindly fly driver. He tells David that ‘If you go up there, pointing with his whip towards the Heights, and keep right on till you come to some houses facing the sea, I think you’ll hear of her. My opinion is she won’t stand anything, so here’s a penny for you.’ The Heights the fly driver was referring to are the Western Heights. With the money the fly driver has given him, David returns to the baker’s shop and buys a loaf of bread. He eats it as he takes the path up the Heights.

Betsey Trotwood outside her cottage on Western Heights on David’s arrival. Etching by Phiz for David Copperfield 1849. Wikimedia

The way the fly driver pointed would most likely have taken David along Queen Street near the southwest corner of Market Square, which eventually would have brought him out onto Cowgate Hill. The path would then have taken David along the eastern edge of Cowgate Cemetery until he reach the foot of the Sixty-Four steps that led up the Heights to the Military Barracks. On the left, the seaward side, was Pilots Meadow, now allotments. The Meadow had been purchased in 1689 by the Cinque Ports Pilots and on the seaward side, were cottages for the Pilots, one of which was for the most senior, Upper Case Pilot. Close by the cottages was another flight of steps that led down to Snargate Street to enable the Pilots to get to their boats quickly. By 1730, a wooden Pilot’s lookout had been built on Cheeseman’s Head, where these days, Admiralty Pier leaves the shore and Pilot’s Field, as it was called, was let out for grazing to raise money for Pilots’ pensions. By Dickens time, Pilots Field had been renamed Pilots Meadow and was a favourite resting place of the author when walking the cliffs. Dickens would have noticed that the senior Pilot’s cottage was larger than the others, with double front bow windows and its own small walled garden. For these reasons, it was believed to be David’s Aunt, Betsey Trotwood’s home which Dickens describes as, ‘A very neat little cottage with cheerful bow windows: in front of it, a square gravelled court or garden full of flowers; carefully tended and smelling deliciously.‘

Although there is no doubt as to the location of Betsey Trotwood’s cottage in Dover, traditionally the lady herself appears to be a composite of two Dover characters plus Dickens imagination. The first lady was Betty Burville, cited by local historian Mary Horsley (c1847-1920), in her 1895 book Memories of Old Dover. Mary Horsley writes that she drew this conclusion from conversations with elderly local folk and confirmed that Betty Burville wore outrageous clothes and lived in the vicinity of Pilots Meadow. Further, locals told Miss Horsley that Betty Burville was, ‘a terror to us children as it being popularly supposed that she ate naughty children, and the horrid old woman encouraged the idea. Naturally the boys were her sworn enemies, and one of my brothers remembers boring a hole with gimlet, in her rain water butt, that she might find it empty in the morning!’ Modern day local historian, Peter Burville has provided further evidence that unequivocally supports Miss Horsley’s thesis. (Dover Society Magazine July 2012 p42 – p43).

The second Dover lady that went to make the character of Betsey Trotwood was based on the reputation of the deceased Sarah Rice (1754-1841), the formidable mother of Dover’s Member of Parliament (1837-1857), Edward Royd Rice (1790-1878). She had lived where the present St James Shopping Centre is situated close to the Woolcomber Street/ Townwall Street junction. Nearby, Thomas Golder (c1819-1859) kept a stud of donkeys that visitors to the town would hire for riding on the seashore. Sarah, very loudly, vehemently and frequently, yelled at these donkeys as they had a habit of invading her beautifully kept garden to eat her plants, in much the same way as Betsey Trotwood’s did!. Further, Sarah was wealthy and belonged to the English middle classes where bathing and cleanliness was part of their social standing.

Western Heights including Pilots Meadow and Snargate Street from Wellington Dock Marina. Dover Harbour Board

Returning to the novel, once David has convinced his aunt of his identity she asks the advice of Mr Dick, her companion, what to do with him. Mr Dick responds by saying that he should be washed, to which Betsey calls out, ‘Janet, … and turning with a quiet triumph which I did not understand, (says) Mr Dick sets us all right. Heat the bath!’ Although Sarah had died at the time Dickens started to come to Dover she was a well-remembered character and an active and formidable business associate of the Latham Bank, one of Dover’s two banks. The other bank was Fectors, whose manservant, Henry Stone (1805-1892), throughout Dickens time, owned the Apollonian Hall. This was close to the Pilots Steps on Snargate Street and where Dickens always performed when he came to Dover.

In the 1920s and 1930s, author Walter Dexter (1877-1944) wrote a series of books about Charles Dickens in various localities throughout the UK. One of these, Kent of Dickens, was published in 1924 and he rubbished Dover’s claims writing, ‘The location of Betsey Trotwood at Dover is purely imaginary…’. He went on to say that ‘there is no record of Dickens having stayed for any length of time until 1852, three years after he had introduced it by name…’ This account came under attack from Dover’s intelligentsia, most notably solicitor John Hewitt Mowll (1891-1948), who not only provided hard evidence to the contrary but pointed out that Dickens came to Dover as part of an acting troop when they performed at the Apollonian Hall long before he wrote David Copperfield. Further, Mowll wrote, the great author had crossed the Channel to go to France from Dover and returned using the same route more than once. Finally, Mowll stated that if Dexter was correct why did Dickens emphatically state that the town, which David came, to find his aunt was Dover – there was no logic to Dexter’s claims. Sadly, Walter Dexter’s claims over this aspect of the David Copperfield story, has been reiterated on the internet as fact.

Smith’s Folly, East Cliff from an original drawing by Rawle and engraved by John Nixon in 1801. Dover Library

Peggotty, the housekeeper in David Copperfield, takes David to Yarmouth in East Anglia, when he is a child, to stay with her brother and his family. This was at the time of David’s mother’s unfortunate marriage to Murdstone. Dickens tells us that the family lived in an upturned boat and up to 1930, when Dover was effectively cauterised from David Copperfield, it was assumed that the Peggottys dwelling was based on Smith’s Folly at East Cliff. Back in the early 1800s, Army Captain John Smith, the father of Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith (1764-1840) known by his middle name of Sidney, built his home at East Cliff. This was out of upturned boats and known as Smith’s Folly and became a tourist attraction. Although there are a number of other interesting characters in the book, none have a direct connection with Dover. As for the fate of David, he finds happiness with Agnes Wickfield of Canterbury, the daughter of Betsey Trotwood’s solicitor. Meanwhile, the Peggottys and the Micawbers, like a great many other folk from Britain in the ‘Hungry Forties’, emigrated to Australia.

10 Camden Crescent, where Charles Dickens stayed in 1852. Destroyed in World War II. T W Tyrrell The Dickensian 1908

After the publication of David Copperfield, Dickens tells us that he travelled by train to Dover before going to Paris in 1851. From his description it can be assumed that this was Dickens first journey by train to the town. Both the comfort and the speed of the train astounded him. In an article published shortly after the journey, he asks what had SER ‘done with all the horrible little villages we used to pass through, in the diligence? (A Flight published 1851). The diligence was the four-wheeled stagecoach. The following year, 1852, Dickens had an extended stay in the town at 10 Camden Crescent. This part of the Crescent was destroyed during World War II (1939-1945) but on the present last house there is a Dover Society plaque in honour of the great writer.

Dickens had intended to stay at number 10 from July to October 1852 but this was interrupted by a tour with amateur players, taking in London, Nottingham, Derby, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Sunderland, Sheffield, Manchester and Liverpool. As soon as the tour was over, he returned to Dover. His friend, the novelist Wilkie Collins (1824-1889) visited while Dickens was at Camden Crescent and wrote a vivid account of the regulated way the household was run. Breakfast at 08.10 hours, afterwards writing until 14.00 hours then walking. Dinner was at 17.30 hours and bed between 22.00-23.00hours. Walking was an integral part of Dickens life in Dover confirmed in a letter dated 22 July 1852, to popular novelist Mary Louisa Boyle (1810-1890) daughter of Vice-Admiral Sir Courtenay Boyle (1770-1844) and friend of Georgy Hogarth. ‘My Dear Mary, you do scant justice to Dover. It is not quite a place to my taste, being too bandy – I mean musical, no reference to its legs – and infinity too genteel. But the sea is very fine, and the walks are quite remarkable.’

Bleak House

Pier District maritime quarter that, it is said, provided the atmosphere for Tom-all-Alone’s in Bleak House. Dover Museum

At the time Dickens was working on Bleak House the working title was Tom-all-Alone’s. Although the story is set in London, the slums described were common to most British towns and in Dover parallels have been drawn with the densely populated Pier district of Dover. This was close to the harbour and the SER Town railway station and was the maritime quarter of the town. It had grown, without any form of planning, on land reclaimed from the sea. The maze of streets that made up the Pier District nestled under the Western Heights, which had been heavily fortified during the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) and in Dickens time was one of the country’s major garrisons. Because of the proximity to the harbour, town and garrison, the mercantile area of Dover had developed in the Pier District and included Snargate Street, Limekiln Street and Strond Street.

Bleak House was published in 20monthly parts from March 1852 to September 1853 and it has been argued that Dover’s Pier District helped to provide the atmosphere for Tom-All-Alone’s district in the book. This district, Dickens tells us, is close to Lincoln Inns Fields and the High Court of Chancery. The latter had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of lunatics and the guardianship of infants. The Court of Chancery had a bad reputation for long delays and it is this aspect where parallels can be drawn with another district in Dover at the time Dickens was working on Bleak House. A slum that specialised in prostitution for the military had evolved from the time of the Napoleonic Wars on the north eastern part of Western Heights. This district more closely fits the description of Dickens account of Tom-All-Alone’s than the Pier District. For Dickens writes, ‘It is a black, dilapidated street, avoided by all decent people; where the crazy houses were seized upon, when their decay was far advanced, by some bold vagrants, who, after establishing their own possession, took to letting them out in lodgings.’

Military Hill – building started to take place after the 1860 ruling as can be seen in this c1900 view from Priory Place. Dover Library

When the garrison on Western Heights was being built during the Napoleonic Wars a Military Road was laid, part of which ran from York Street to part way up Military Hill. The owner of the immediate adjacent land was James Gunman (1747-1824) who sold it to Dover Corporation, with the intention of building a small housing estate. However, the War Office barred none military personnel using Military Road. The council protested but when the Government’s Privy Council assessed the situation they supported the War Office. A legal impasse resulted that lasted nearly 50years – similar to that described in Bleak House. This cost Dover Corporation a great deal of money in legal expenses (see Western Heights Part I) before the situation was partly sorted out in 1860 when building took place. Albeit, it was over 150 years after Dover Corporation first purchased the land, before the lower part of Military Road was formally dedicated for public use by the Ministry of Defence!

Immediately following the 1852 stay in Dover, Dickens left for Boulogne with Kate but was back in England for the publication of Bleak House, in 1853. He had fallen out of love with Kate and the self imposed demands of his work to earn money were taking their toll, with Dickens saying that he felt ‘as if I had been thinking my brain into a sort of cabbage net.’ (1990 biography by Peter Ackroyd). In March 1849 Dickens launched the weekly magazine, Household Words. This continued until 1859, when it was succeeded by All the Year Round, which continued until 1870, when Dickens died. In these two periodicals, Dickens mainly published short stories but he also published the novel Hard Times, between April and August 1854. The Child’s History of England was also published in parts in Household Words and then in three volumes between 1852 and 1854. Respected critic, Derek Hudson (1911-2003) described the work as a ‘boy’s book, founded on a strong sense of social justice,’ and was seen as typical of such books published in the mid 19th century.

Out of Season Dover Stay 1856

By March 1856, Dickens financial position was definitely looking up and he was starting work on his novel Little Dorritt when he heard that Gads Hill Place was on the market. This he bought for £1,760 with the intention of use it as a summer retreat. However, his relationship with Kate had reached rock bottom and his in-laws, whom he disliked, were staying at Tavistock Place. Dickens escaped, staying at Dover’s Ship Inn on Custom House Quay, arriving on 15 March and leaving on 23 May (Dover Telegraph’s of 1856), when, apparently, the Hogarth’s left the family home. Custom House Quay was on the landward side of Dover’s inner harbour or Bason, later following refurbishment it was renamed Granville Dock.

The entrance into the Bason, later the Granville Dock, with Custom House Quay at the rear. On the facing left side of the entrance was a tower containing a large compass and on the right, the red face with a white rim clock tower that Dickens talks about in Out of Season. Dover Library

Here, Dickens settled down to work on Little Dorritt but his emotional state was such that he found it impossible. He described how he felt in Out of Season, published in Household Words on 28 June 1856, and his time in Dover was juxtaposed into three days. Dickens wrote, ‘I had scarcely fallen into my most promising attitude, and dipped my pen in the ink, when I found the clock upon the pier – a red-faced clock with a white rim – importuning me in a highly vexatious manner to consult my watch, and see how I was off for Greenwich time. Having no intention of making a voyage or taking an observation, I had not the least need of Greenwich time, and could have put up with watering-place time as a sufficiently accurate article. The pier-clock, however, persisting, I felt it necessary to lay down my pen, compare my watch with him, and fall into a grave solicitude about half-seconds. I had taken up my pen again, and was about to commence that valuable chapter, when a Custom-house cutter under the window requested that I would hold a naval review of her, immediately. It was impossible, under the circumstances, for any mental resolution, merely human, to dismiss the Custom-house cutter, because the shadow of her topmast fell upon my paper, and the vane played on the masterly blank chapter.’

As he had previously done, while in Dover, Dickens went for long walks, some of which were recounted in Out of Season. On one walk, of ten miles, he came to a seaside town without a cliff – probably Deal – ‘which, like the town I had come from, was out of season too. Half the houses were shut; half of the other half were to let; the town might have done as much business as it was doing then, if it was at the bottom of the sea. Nobody seemed to flourish save the attorney; his clerk’s pen was going in the bow-window of his wooden house; his brass door-plate alone was free from salt, and had been polished up that morning. On the beach, among the rough luggers and capstans, groups of storm-beaten boatmen, like a sort of marine monsters, watched under the under the lee of these objects, or stood leaning forward against the wind, looking out through battered spy-glasses.’

Of Dover, he wrote, after returning from a twenty mile walk, ‘I came among the shops, and they were emphatically out of season. The chemist had no boxes of ginger-beer powders, no beautifying sea-side soaps and washes, no attractive scents; nothing but his great google-eyed bottles, looking as if the winds of winter and the drift of salt had inflamed them. The grocers’ hot pickles, Harvey’s Sauce, Doctor Kitchener’s Zest, Anchovy Paste, Dundee Marmalade, and the whole stock of luxurious helps to appetite, were hybernating somewhere underground. The china-shop had no trifles from anywhere. The Bazaar had given in altogether, and presented a notice on the shutters that this establishment would re-open at Whitsuntide, and that the proprietor in the meantime might be heard of at Wild Lodge, East Cliff…’ East Cliff, at the east end of the bay was, at that time, a recent housing development.

While taking these walks Dickens would chat with locals and on one occasion, having gone into a hostelry for something to eat, he joined a landsman and two boatmen. They were ‘seated on a settle, smoking pipes and drinking beer out of thick pint crockery mugs – mugs peculiar to such places, with parti-coloured rings around them, and ornaments between the rings like frayed-out roots. The landsman was relating his experience, as yet only three nights old, of a fearful running-down case in the Channel…‘ Dickens went on to tell his readers that the landsman finished his tale by saying that he ‘saw hovellers, (long shore boatmen), to a man leap in the boats and tear about to hoist sail and get off, as if they had everyone of ’em gone, in a moment, raving mad. But they knew it was the cry of distress from the sinking emigrant ship.’

Dickens returned to Tavistock House after his parents-in-law left, then in June 1858 he and Kate separated. She lived for awhile at their London home while Dickens made Gads Hill Place a permanent residence for himself and their children with the exception of his eldest son, Charles, known as Charley (1837-1896). Charley, at that time was working at the merchant Barings Bank (1762-1995) in London so he stayed with his mother while Georgy, Kate’s sister became Dickens housekeeper at Gads Hill Place. At about this time Dickens started to undertake speaking tours, which proved so profitable that the state of his finances were no longer a problem.

A Tale of Two Cities

Simultaneously in All the Year Round, published in monthly parts between June and December 1859, Dickens twelfth novel, A Tale of Two Cities was published. The story is set at the time of the French Revolution (1789-1799) in London, Paris and journeys between the two capitals. Some years ago, I undertook a piece of research showing the Dickens 1856 stay in Dover, played a part in many of the themes of the book. After a presentation to the Dickensian Fellowship, my work was published in the Dickensian, (Summer 2002 pp 140-144). In A Tale of Two Cities preface, Dickens states that, ‘the main idea of this story’ was conceived while acting ‘with my children and friends, in Mr Wilkie Collins’s drama The Frozen Deep.’ This was presented at Tavistock House, by Charles Dickens, family and friends on the Twelfth Night, 6 January, 1857. In the preface, Dickens acknowledges the 1837 work of the Scottish philosopher, Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), French Revolution and it is known that Dickens had read the book over 500 times!

Gun Turret on Admiralty Pier, erected in the 1850s in the face of possible threats from France, seen from the former Prince of Wales Pier. AS 2015

Although France had been an ally of Britain during the Crimean War (October 1853 – February 1856), by late spring 1856, the political relations between the two countries were strained. This was due to Emperor Napoleon III (1852–1870) reasserting France’s authority in Europe. Due to the perceived threat, the British Government’s chose Dover as a primary garrison. This led to the most extensive and expensive programme of defence constructions up to that time in the UK and included the erecting of the Gun Turret on Admiralty Pier and the defensive works on Western Heights at a cost of £37,577. It was generally known what was happening and why, and this could be another contributory factor in Dickens decision to base a novel on France at the time of the French Revolution. That had been the major event that had preceded the Napoleonic Wars and it was the Wars that led to the original massive military garrison on Western Heights.

A Tale of Two Cities opens in 1775 with a description of the situation in Paris and London that led up to the Revolution in France, neither of which are flattering. In the second chapter, entitled The Mail, Dickens tells us that it is a late Friday night in November and the mail coach from London to Dover is climbing up the steep Shooters Hill, Greenwich, on the old London-Dover Road (formerly the A2). The passengers have had to get out and walk ‘because the hill, and the harness, and the mud, and the mail, were all so heavy, that the horses had three times already come to a stop, besides once drawing the coach across the road, with the mutinous intent of taking it back to Blackheath.’ Travelling in the coach is Jarvis Lorry, agent for Tellson’s Bank in London. He is planning to go across the Channel from Dover, to France and then on to Paris. While on the coach he receives a mysterious message and sends back the answer, ‘Recalled to Life’.

Eventually the mail coach arrives at the coach terminus in Dover in the late morning. This Dickens tells us is the Royal George which is most likely to be a pseudonym for the Ship Inn, where Dickens had recently stayed. There was a Royal George at the time of Dickens but according to Paul Skelton’s website on Kent pubs (dover-web.com), it was on Priory Street and did not exist at that time of the French Revolution. Moreover, the Ship Hotel was the designated final stop for the London mail coaches that had been introduced in 1786. In the book, at the hotel, Mr Lorry is given the ‘Concord‘ bedchamber that was used for affluent mail coach passengers. The Concord was also the Ship’s best suite consisting of two rooms overlooking the Bason harbour. While staying at the Ship Inn, Dickens wrote to Wilkie Collins saying that he had ‘two charming rooms … overlooking the sea in the gayest way, ’

Mr Lorry has a late breakfast and then goes for a walk around the town. This Dickens describes by alluding to smuggling, which was one of the town’s main industries at the time the novel is set (see Shipbuilding part 2) ‘The little narrow crooked town of Dover is itself away from the beach, and ran its head into the chalk cliffs, like a marine ostrich. The beach was a desert of heaps of sea and stones tumbling wildly about, and the sea did what it liked, and what it liked was destruction. It thundered at the town and thundered at the cliffs, and brought the coast down madly … A little fishing was done in the port and a quantity of strolling about by night, and looking seaward, particularly at those times when the tide made and was near flood. Small tradesmen who did no business whatever, sometimes unaccountably realised large fortunes and it were remarkable that nobody in the neighbourhood could endure a lamplighter!’

Dr Manette in the Bastille by Phiz – Hablot Knight Browne – for Charles Dickens Tale of Two Cities. Wikimedia

On returning to the hotel Jarvis Lorry meets, by appointment, Lucie Manette also referred to as ‘Mam’selle’, who is French-born but brought up in England. He tells Lucie that her father, the physician Dr Alexandre Manette, is not dead but has for many years been held a prisoner in the Bastille, Paris, and that he had recently been released! There is little doubt that the character of Lucie is based on that of Ellen Ternan (1839-1914), whom Dickens met in 1857 and not long after became his mistress.

Banking on Dover, by Lorraine Sencicle published in 1993, gives a factual account of the Fector and Latham banks of Dover between 1685 and 1846.

At the end of 1993, my academically acclaimed book, Banking on Dover, was published. It is a factual account of two diverse banking families who lived in Dover between 1685 and 1846 – with one growing out of one of the first High Street banks in the country that was started in Dover. This was the Fector Bank and they made their fortune by financing smuggling operations, backing privateering ships and land deals. An important member of the family was John Minet Fector, (1754-1821) who, prior to the Napoleonic Wars effectively became East Kent’s ‘Godfather’. He was charming, wealthy, well educated, confident and very popular. Fector’s greatest friend was George Jarvis (1774-1851) who, following the Wars, managed the Fector Bank while Fector was abroad. After Fector’s death. George Jarvis, also of a charming disposition, inherited from both his mistress and her mother, a magnificent estate in Lincolnshire where he died in 1851 aged 77 (See Dynasty’s of Dover parts 5i and 5ii Fector – Jarvis).

When I re-read A Tale of Two Cities, sometime after the publication of my book, I was struck by the fact that Dickens had called one of the first two main characters we meet, Jarvis Lorry and the other Lucie Manette. These names were similar to those who played important roles in the Fector family. John Minet Fector’s father, Peter Fector (1723-1814), had worked for his uncle, Isaac Minet (c1677- 1745) and initially the bank was the Minet bank! Not only was Fector’s middle name Minet, his wife’s maiden name was Laurie and his best friend was a Jarvis! Further, Fector’s son, also called John Minet Fector (1812-1868) took over the bank when he was old enough and amalgamated it with the National Provincial Bank. Shortly after, in order to become the Chairman of National Provincial Bank, he took his mother’s maiden name – that of Laurie! Spelt differently but sounding the same as the Lorry in A Tale of Two Cities! Another coincidence is that Fector junior, following his father’s death had effectively been brought up by the faithful servant, Henry Stone, who subsequently became the proprietor of the Apollonian Hall, There, as noted above, Dickens always performed or gave talks when in Dover!

During his 1856 stay, as already recounted, Dickens took a number of long walks. After one walk, he tells us that he went back to the Ship and debated on whether to go and see the Black Mesmerist or to settle down and read a book by the hotel fire. He opts for the latter and tells us in Out of Season, ‘…indeed I had not left France alone, but had come from the prisons of St Pélagie with my distinguished and unfortunate friend Madam Roland (in two volumes) which I bought for two francs each at the book-stall in the Place de la Concorde.’ Sainte-Pélagie was a prison in Paris from 1790 to 1899.

Three women knitting in front of the guillotine by John Mclenan for Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Wikimedia

Madam Roland, was Jeanne Manon Roland (1754-1793), an engraver’s daughter who was politically minded, married and worked closely with her politically active husband. In 1792, her husband held one of the highest posts in France but it was a poison chalice for they soon after fell from grace and he was sent to Sainte-Pélagie prison. With his wife’s help, he escaped but Madam Roland remained a prisoner and was guillotined on 17 November 1793. Two days later her husband committed suicide outside Rouen. Of Madam Roland in the books, Dickens, tells us that ‘We spent some sadly interesting hours together on this occasion, and she told me – Madam Roland – again of her cruel discharge from the Abbaye, and of her being re-arrested before her free feet had sprung lightly up half-a-dozen steps of her own staircase and carried off to the prison which she only left for the guillotine.’

A Tale of Two Cities, is a story with two halves. After rescuing Dr Manette, Lucie and Jarvis Lorry bring him back to England but five years later they are obliged to testify in a treason trial. This is held at the Old Bailey, in London where the accused is Charles Darney, who for reasons unclear frequently goes to France and therefore is accused of sedition. However, Darney is acquitted after his counsel, C J Stryver, points out that he closely resembles Sydney Carton. The persona of Sydney Carton, is said to be based on the character Richard Wardour, in The Frozen Deep, that was played by Charles Dickens in his Twelfth Night production!

We are told that Carton is a brilliant English lawyer who loves Lucie Manette but drinks heavily and is a bit of a wastrel. In his first manuscript, Dickens gives Carton’s first name as Dick, but finally chooses Sydney after Algenon Sydney (1623-1683). He was a former Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports during the Commonwealth Period (1649-1660) and was charged with complicity in the Rye House Plot (1683) along with Lord William Russell (1639-1683). Both were tried by Judge George Jeffries (1645-1689) and executed in 1683. Dickens dedicated Tale of Two Cities to Lord John Russell (1792-1878) after whom Russell Street was named, was a descendent of the hapless Lord William.

The character of Charles Darney is said to be based on an actor, but in my thesis I made the case that like John Minet Fector, Charles Darney was wealthy, well educated and assured. Further, on Monday 22 April 1799, during the Napoleonic Wars, the Officers of the militia regiments, quartered at Dover Castle, all withdrew their accounts from the Fector Bank. Sometime during that day, John Minet Fector left his home and disappeared into Dover’s back streets. His crime was aiding the enemy and a reward of £2,000 was offered for his apprehension. This sudden allegation was based on the presentation of an 800 page report to the Directors of the East India Company in London, by Jacob Bosanquet (1755-1828).

King George I, John Minet Fector’s 70ton sloop and the fastest ship on the cross Channel packet run in which he made many surreptitious crossings of the Channel during the time of the French Revolution. Gordon Ellis. A model of the ship can be seen at Dover Museum

Fector was also accused of the ‘illicit trade against the chartered rights of the East India Company that amounted to treason.’ The main evidence rested on the fact that Fector was the leader of Dover’s smuggling fraternity and that from the start of the Revolution he had made numerous surreptitious trips to France, in his Dover built 70ton sloop, King George I, the fastest ship on the cross Channel packet run. The case against Fector was overwhelming but when the verdict was given, much to everyone’s surprise, he was exonerated!

Cover by Phiz – Hablot Knight Browne – for Charles Dickens A Tale of Two Cities, published in All the Year Round July 1859. Wikimedia

At the time A Tale of Two Cities was set, Fector, lived at Pier House, on Strond Street. This fronted onto Custom House Quay and was next to the Ship Inn. During the 1840s the Fector bank amalgamated with the National Provincial Bank and Fector’s son sold Pier House to John Birmingham (1797-1875), the owner of the Ship Inn. He converted Pier House into suites, one of which was the Concord, which Dickens occupied overlooking Custom House Quay. In 1814, Louis XVIII of France (1814-1824) had stayed at Pier House as a guest of Fector, by which time it was already known that Fector had helped many French aristocrats to escape from Madam Guillotine during the Revolution!

On 7 September 1853, the opulent Lord Warden Hotel, close to Admiralty Pier, when Dover Station opened on 6 February 1844, renamed Town Station in 1863, John Birmingham was asked to become the manager. He eventually took the position and when he did, Dickens stayed at the hotel rather than the Ship Inn. In a letter, dated 1863, Dickens referred to John Birmingham and his wife Mary, as ‘my much esteemed friends.’ So they too, along with Henry Stone, would, no doubt, have told Dickens about John Minet Fector and the treason trial.

Uncommercial Traveller and Talks

Simultaneously with the publication of Tale of Two Cities, what has been described as the set of Dickens finest occasional essays, was The Uncommercial Traveller and published between 1861 and 1866, while a further eleven were added in a posthumous edition of 1875. From December 1860 to August 1861 he also published Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend was published between May 1864 and November 1865. However, in the autumn of 1864, the continual demand, some of which was self imposed, on Dickens was telling on his health. He complained of suffering from a boiling head, decided to recuperate by the sea and chose Dover, staying with the Birmingham’s at the Lord Warden Hotel for about a week.

Dover received special treatment in Chapter 18 of The Uncommercial Traveller, a series of essays mentioned in the previous paragraph and cover a wide range of travel observations written in a style that reflected Dickens journalistic background. He crossed that Channel at least sixty times during his life and in The Calais Night Mail, Dickens described a train journey, travelling on the locomotive’s footplate of the night mail train from London to Dover. The train driver on the outward journey was Tom Jones and the stoker John Jones. The train left London Bridge at 20.30hours. A description of a Channel crossing had previously been described in Chapter 7 of The Uncommercial Traveller, in Travelling Abroad. In that story Dickens tells his readers about crossing the Channel on the Dover packet to Calais after exploring Europe.

Dickens writes, ‘As I wait here on board the night packet, for the South-Eastern Train to come down with the Mail, Dover appears to me to be illuminated for some intensely aggravating festivity in my personal dishonour. All its noises smack of taunting praises of the land, and dispraises of the gloomy sea, and of me for going on it. … A screech, a bell, and two red eyes come gliding down the Admiralty Pier with a smoothness of motion rendered more smooth by the heaving of the boat…. We, the boat, become violently agitated – rumble, hum, scream, roar, and establish an immense family washing-day at each paddle-box. Bright patches break out in the train as the doors of the post-office vans are opened, and instantly stooping figures with sacks upon their backs begin to be beheld among the piles, descending as it would seem in ghostly procession to Davy Jones’s Locker. The passengers come on board; a few shadowy Frenchmen, with hatboxes shaped like the stoppers of gigantic case-bottles; a few shadowy Germans in immense fur coats and boots; a few shadowy Englishmen prepared for the worst and pretending not to expect it.’

Of inclement weather and the Channel crossing, Dickens wrote in a letter to Georgy of November 1861, ‘The storm was most magnificent … the sea came in like a great sky of immense clouds, for ever breaking suddenly into furious rain … the unhappy Ostend packet, unable to get in or go back, beat about the Channel all Tuesday night and until noon yesterday, when I saw her come in, with five men at the wheel, a picture of misery inconceivable.’ The Calais Night Mail promised a rough Channel crossing but a content Dickens, who was used to crossing the Channel in bad weather on an unstabilised packet steamer, wrote, ‘The wind blows stiffly from the Nor-East, the sea runs high, we ship a deal of water, the night is dark and cold, and the shapeless passengers lie about in melancholy bundles, as if they were sorted out for the laundress; but for my own uncommercial part I cannot pretend that I am much inconvenienced by any of these things.’

In the essay Travelling Abroad, Dickens gives an account of the stage coach journey to Dover. Describing his arrival into the town on what is now the Old Folkestone Road, he wrote, ‘Over the road where the old Romans used to march, over the road where the old Canterbury pilgrims used to go, over the road where the travelling trains of the old imperious priests and princes used to jingle on horseback between the continent and this Island through the mud and water, over the road where Shakespeare hummed to himself, ‘Blow, blow, thou winter wind,’ as he sat in the saddle at the gate of the inn yard noticing the carriers; all among the cherry orchards, apple orchards, corn- fields, and hop-gardens; so went I, by Canterbury to Dover. There, the sea was tumbling in, with deep sounds, after dark, and the revolving French light on Cape Gris Nez was seen regularly bursting out and becoming obscured, as if the head of a gigantic light- keeper in an anxious state of mind were interposed every half- minute, to look how it was burning.’

It was about 1857 that Dickens had started undertaking public reading tours. These covered characters and other aspects from his published works and held at numerous venues up and down the country. In Dover, they were always held at the Apollonian Hall, Snargate Street and he stayed at the Ship Inn until John Birmingham moved from there to take over the Lord Warden Hotel. Of note the Apollonian Hall was demolished in 1930 to enable Dover Harbour Board to widen the then Commercial Quay adjacent to Wellington Dock.

Dickens quoted passages from his works and acted each part with such conviction that the audience felt convinced that each character had come to life. His only props were a tall wooden table with a baize cover and a small lectern. These events were always well attended, received and covered in the local papers. On Tuesday 5 November 1861, he gave a two-hour presentation from Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby. Of the occasion, the Dover Express reported that ‘at times the silence in the crowded room was profound. The characters were brought upon the stage like old friends with new faces – to the bounded delight of the audience, who laughed and applauded almost unceasingly from beginning to end.’ While Dickens later wrote, ‘… the audience with the greatest sense of humour is certainly Dover. The people in the stalls see the example of laughing, in the most curiously unreserved way; and they laughed with such cordial enjoyment, when Squeers read the boys’ letters, that the contagion extended to me. For one couldn’t hear them without laughing too … So I am thankful to say, all goes well, and the recompense for the trouble is in every way great.’

Charles Dickens advert that he is to speak at the Apollonian Hall Snargate Street. Dover Express 10.10.1861

Albeit, there were complaints. Draper, John Agate (1821-1902), who had a business at 128 Snargate Street and was active in Dover commerce. He also voiced concerns over the welfare of shop assistants and was the chief mover in the establishment of the Dover Trades Holiday and half-day off a week for full time shop assistants. The half-day off a week or early closing days, as they were called, lasted until 1970s but other shopkeepers complained and ostracised Agate over holidays with pay. One evening Agate took his family along to hear one of Dickens public readings. Being aware the Apollonian Hall could become so crowded that people were turned away, the family arrived early. Due to some confusion however, they were not allowed to enter the venue and therefore missed the presentation. Agate was angry and wrote Dickens a terse letter. Dickens responded with a kind and apologetic letter, which pleased Agate so much, that he displayed it in his shop window. Agate also announced that the letter was better than attending the talk as he could keep it whereas a talk would soon be forgotten!

Having come to Dover, staying at the Lord Warden Hotel, when he was not well in 1864, when Dickens doctors advised him to take rest, he returned once again to the town. There is little doubt that the demands of continually producing novels and essay plus the strenuous round of public readings had taken their toll on Dickens health. Although John Birmingham still held his post at the Lord Warden Hotel he was heavily involved in local politics and spending increasingly less time at the hotel. In consequence, Dickens frequently stayed with artist and later photographer, Lambert Weston (1806-1895), who owned two houses in Waterloo Crescent, on the seafront. One of these was managed by Lambert’s housekeeper, believed to be Eliza Paddon, and let to visitors such as Dickens. By that time, Dickens had a habit of getting up later than formerly and on fine days would walk up to Pilots Meadow, taking his writing materials to lie on the grass and work.

In the afternoon of 9 June 1865, Dickens was travelling on the SER Folkestone to London boat train with Ellen Ternan and her mother, Frances (c1803-1873). Engineering works were being undertaken on the Staplehurst, Kent, viaduct and a length of track had been removed. To warn train drivers SER had followed the Board of Trade regulations and placed a man with a red flag to warn drivers. The man should have been placed 1,000 yards away from where the track had been removed and the spacing of a number of telegraph poles would have determined this. In reality along that stretch of line, the poles were unusually placed closer together so the number that should have equated with 1,000yards only gave a distance of 554 yards and the train did not have sufficient time to stop. The train derailed and plunged into the riverbed below killing 10 people and injuring 40. The party survived and Dickens helped in the rescue but the Staplehurst rail disaster had a profound effect on him, from which, it was said, he never recovered.

Coming to Dover regularly and staying at Waterloo Crescent, Dickens spent his time in the town as he had before the railway accident. But in 1868, against medical and his friends advice he decided to under take another reading tour of the United States. This proved to be very popular and Dickens earned in the region of £20,000 but on return to England, it was apparent that he was far from well. Nonetheless, he worked on a new novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which he never finished. Dickens died of a stroke at Gads Hill Place on 9 June 1870, the fifth anniversary of the Staplehurst disaster. In Dover, as in many other towns and cities, the people mourned and Queen Victoria (1837-1901), wrote in her diary ‘He is a very great loss. He had a large moving mind and the strongest sympathy for the working classes.’

First Presented: 21 December 2015

Rewritten and Presented: 8 September 2018