At the top of Biggin Street, next to the Maison Dieu, are three cannons, said to have been brought back from the Battle of Waterloo (1815). Up until the 1920s, they were on display outside of a High Street shop that belonged to Matthew Pepper. The Pepper family is one of the oldest in Dover, with a number of members playing prominent roles in the town’s history.

Thomas Pepper was Mayor in 1559, 1563, 1565 and 1567 and from documents, we know that he held land ‘Above the Wall’. This was the area now occupied by the present day almshouses and Adrian Street. He also owned land in Elms Vale and Maxton. As Mayor, Thomas ruled with a firm hand, inflicting heavy fines on two Jurats and was instrumental in sending Roger Wood, the Town Clerk, to gaol! He also stop religious feuding prevalent at the time with emissaries, acting on behalf of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), reporting back to the Queen that, ‘The Maier, Jurats and Comynalte were all in p’feact amyte and concord thanks to yeomen unto God and hath openle pumiced soe to contynewe by God’s Grace.’

In Thomas’s final year as Mayor a document was published that raises doubts over the accepted site of Biggin Gate. This is generally believed to be near the junction of New Street and Biggin Street, where a plaque can be seen today. The document concerns the letting of a property and implies that Biggin Gate was further south. Biggin Gate was removed by order of the Common Council in 28 June 1762.

Thomas Pepper died about 1575 and was buried in St Peter’s Churchyard, site of the present day Church Street / Lloyds Bank, Market Square. He wrote his Will the year before and bequeathed his property in Elms Vale to a member of his family that was eventually sold on to the Stringer family. The Maxton property also went to a relative and was eventually sold. The profits from other property were distributed equally between to the poor within the parishes of St Mary’s, Dover and Hougham. Originally, the money was used, once a year, to make sixpenny loaves that were then given to the poor.

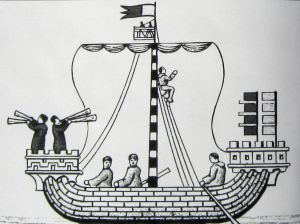

The next member of the Pepper family of note is Luke who was the Master of the Almshouses and Mayor of Dover from September 1634 for two years. At the time, Charles I (1625-1649) was making demands for ship-money. The Cinque Ports, of which Dover was a key member, by their charters had for centuries provided ships and men for what was effectively the country’s navy. However, by the time of the Armada (1588), the Cinque Ports were only able to send five ships.

Although the country was not at war when Charles I asked for ship-money the navy was in a poor state. The writ stated that the authority it was addressed to, had to provide a ship of a certain tonnage, armed with a certain number of guns, equipped with a specific crew, supplied with provisions for six months and to be ready for service of the King at a certain sea-port on a set day. The cost of each ship as described in the writ was estimated at an average of £10 per ton. If the authority could not provide the said ship then they had to pay an equivalent tax and it was expected that this would annually raise about £10m. It was left up to the Sheriffs of each county to undertake the assessment of the authorities in their jurisdiction and the Cinque Ports were rated at one ship of 800-tons with 320 men. On this basis, Dover was expected to pay £330 per year from 1635 and for the following four years, with a 20% discount if paid promptly.

The first demand for the annual ship money was instigated by Lord Finche of Fordwich, in 1635, four years later Dover, along with the rest of Kent, had not paid it or any subsequent demands. The county, in retaliation, was accused of ‘having a sad lack of religion, being sympathetic to Catholics, and a large number of rogues and ale houses.’ Following this the Cinque Ports were ordered to provide both ship money and 300 soldiers with their clothing and other disbursements or pay £3 per man. The Ports petitioned Parliament saying that they could not afford it but by the time the complaint was to be heard, Parliament had been dissolved. The Civil Wars broke out in 1642 and Charles I was beheaded in 1649. Throughout all of this Luke was one of the leading protagonists.

At the Restoration of Charles II (1649-1685) in 1660, John Pepper was an attorney and Common Councilman and was appointed Town Clerk the following year. Although the King promised to treat his subjects’ religious convictions fairly, within two years members of the Corporation were compelled to sign a document stating that they conformed to the prevailing religious doctrine – Anglicanism. Seven Jurats and twenty-three Common Councilmen refused and were removed from office – John signed.

Not long after John was appointed solicitor to the Cinque Ports Court of Brotherhood and later successfully obtained a renewal of the Cinque Ports Charter from Charles II without a great deal of alteration. However, Dover’s Charter, given by Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was called in and because of the religious descent in the town at the time (See Dynasty of Dover Part I – Stokes). A new Charter, it was envisaged by the King, would weaken the way the town was governed. John fought hard against this but in 1683, he died. Within weeks, a new Charter was issued and the power of electing the Town Clerk transferred to the Privy Council in London.

James II (1685-1669) came to the throne in 1685 and the Privy Council, in accordance to the new Charter, chose the Town Clerk. This was a Paul Pepper who was not a close relation of John’s nor was he a member of Dover’s Common Council. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the Charter was repealed by proclamation on 25 October 1689 and Paul Pepper’s days as Town Clerk were numbered. With the right to elect a new Town Clerk of their own choosing, John Bedingfield was appointed and he held the office for sixteen years. During his time, a Thomas Pepper was the Town’s Sergeant. At sea, another John Pepper, who left Dover as a cabin boy, became Commodore of the East India Company’s fleet.

Matthew Pepper was the family’s next Mayor of Dover. Born in 1841 he trained as an engineer in Ipswich and married Sarah Luckhurst in 1866. Matthew opened a business in the High Street, opposite the present day Charlton Centre where he ran a successful wholesale and retail ironmongery store. It was outside of the shop that kept the three cannons used at the Battle of Waterloo (1815) mentioned in the opening paragraph. In 1883, he stood for the council as a Conservative in Castle ward, but at the request of the executive withdrew to enable William Crundall to stand. The latter went on to be elected Mayor 13 times and was knighted.

Two years later, in November 1885, Matthew was elected for Castle Ward unopposed to fill a vacancy caused by the death of Philip Stiff. He remained on the council until 1913 and was described as keen, witty, original and enterprising – a Radical mind in a Conservative body! Matthew became a magistrate in 1889, appointed Alderman in 1892 and elected Mayor in 1895-6.

That year saw Dover’s boundaries extended and the Pepper boundary stones erected. It was also at this time that the Biggin Gate plaque was put in to position. Further, Matthew was actively interested in international affairs. In an effort to reinforce the then Ottoman Empire, the authorities there had instigated anti-Christian pogroms, particularly in Armenia. Between 1894-1896, it was estimated that some 80,000 to 300,000 Armenians were massacred. However, in Europe very little action was taken. This made Matthew so angry that he wrote to the papers to this effect.

In local politics, Matthew was principally concerned with the administration of the Poor Law, holding an office on the Board of Guardians for Charlton from 1876. The same year as he was elected Mayor, 1895, he was appointed Chairman of the Board, which included the Dover Union – the workhouse that eventually became Buckland Hospital. He preferred helping people to get work or allowing people to stay in their own homes instead of being incarcerated in the workhouse. This, he particularly applied to widows with children, the sick and the elderly, whom, under his leadership, were supported by out-door relief – a combination of money, goods and vouchers. Under his administration, to deal with unemployment, the number of jobs provided by the council increased at the same time the number of healthy inmates of the workhouse fell as they too were provided with paying jobs. This policy, however, came in for fierce criticism, mainly from his own political Party.

Another source of contention was the elderly. Part of the role as Chairman of the Board of Guardians were the Almshouses. The first of Dover’s almshouses was built medieval times but it was not until the 16 and 17 centuries that any more were erected. During the first half of the 19th century, a significant number of almshouses were built and in 1877, Mrs Gorely was persuaded by Dr Edward Ferrand Astley to leave money for ten almshouses below Cowgate Cemetery. Although the number of ‘able bodied’ inmates in the workhouse had fallen, the number of those that required hospitalisation – mainly elderly – was increasing. Matthew took great pains in successfully arguing for the workhouse hospital to be extended so that they could receive nursing care. However, this cost the ratepayers’ £6,790, just for the building works and did not go down well.

In 1903, the yearly income for the almshouses was about £300, derived from ground rents, nominal rents of the almshouses, rents from lands and dividends on Consols belonging to Almshouse charity. Still, reeling from the cost of the workhouse hospital, the following year the council voted that the Board of Guardians were to stop outdoor relief for the elderly – they were to be admitted into the workhouse or do without help. As for the Almshouses, the council stated that they were designed for people who were not absolute paupers so those who were on outdoor relief were to be transferred to the workhouse. The council were supported by the Dover Express of 8 January 1904, with the editor writing, ‘Trustees (of the Almshouses) in future should give help to broken down trades people or persons who have little left and are too aged and broken down to ever hope to get any more and should not have to look to the Poor Law supplement provision.’

Matthew was forced to give way but in April 1907 Dr Astley died and in his Will, he left two-thirds of his £23,000 estate to the Gorely Almshouses. This included increasing the weekly allowances to the inmates so that they would not have to leave their homes and go into the workhouse. On 17 September that year, Matthew’s business on the High Street, was devastated by a major fire following which he slowly withdrew from taking an active part in council affairs. He resigned his position as Chairman of the Board of Guardians, in 1913.

In the 1980s, one of the students I met while teaching at Dover Girls’ Grammar school was the daughter of George Pepper the editor of the Dover Express. He had been appointed editor when Norman Sutton, the father of Terry Sutton, retired in 1964. In 1986 George was promoted to group editor of the South Kent Newspapers with overall responsibility for the Express and its sister paper the Folkestone Herald. In March 1987, the papers were taken over by East Midlands Allied Press, the seventh take over in 18 years. In September that year George was dismissed but received compensation before his case was heard at an Industrial Tribunal. Up to that time, this author was a regular contributor to the Dover Express.

Returning to Matthew Pepper, all the flags were lowered on all the municipal buildings on 24 April 1921, the day Matthew died. Sarah, his wife, died on 28 May 1928 aged 86. By 1925, the shop on the High Street had closed with Turnpenny’s taking over the premises. The block was sold to Drum Development Ltd in 1965, who demolished the properties and built the shops we see today. The three guns that stood outside of Matthew Pepper’s business he bequeathed to the town and are, as noted, adjacent to the Maison Dieu.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 21 & 28 July 2011