In April 1916, Sidney Emile Garcke (1885–1948) presided over a two-day conference in Canterbury. The purpose of the meeting was the possibility of amalgamating a number of East Kent omnibus companies. The result was positive and on 11 August that year, the East Kent Road Car Company (EKRCC) was Registered and on EKRCC commenced operation on Friday 1 September 1916.

The companies that amalgamated were Garcke’s Deal & District Motor Services, Albert Road, Deal – which provided some 18 buses with spare body parts; farmer George Griggs operated the Ramsgate Motor Coaches and provided 5 buses; Fred Wacher and Co, Herne Bay coal merchants, but ran services to Sandwich, contributed 9 buses and Thomas Tilling’s (1825-1893) Folkestone and District Buses, based in Kent Road, Cheriton and had 29 Tilling-Stevens petrol-electric buses. Tilling had set up a passenger transport firm in London and by 1850 was running one of the largest services in the Capital. His sons Richard and Edward joined the firm and in 1897 as Thomas Tilling Ltd, amongst other operations, the Folkestone operation was set up. The Tilling-Steven buses were unusual for although they had a conventional petrol engine they had a dynamo-powered electric motor on the back-axle.

At the time engineer Sidney Garcke, the son of the founder of the British Electric Traction Company (BET) Emile Garcke (1856-1930), was an officer commanding the Berkshire R.A.S.C., Motor Transport. Prior to World War I (1914-1918), Garcke had worked for his father but was particularly interested in motorbuses, having conducted experiments to produce a viable motorbus in Birmingham. After several attempts, due to Birmingham’s undulating terrain, where some nasty accidents had occurred, then in April 1908, Garcke came to Deal. Here, with six of the Bush-built 24-seater buses with Brotherhood engines that he had experimented with, Garcke launched the Deal & District Motor Services. The manager of the new company was engineer Loftus George Wyndham Shire (1885–1963), whom he had worked with in Birmingham. Two years later, Garcke was offered a directorship with the British Automobile Traction Company (BAT) a subsidiary of BET, and became the Managing Director in 1912.

Negotiations that led to the setting up of the EKRCC had taken place at the Canterbury branch of Dover solicitors Mowll & Mowll headed by John Hewitt Mowll (1891-1948). At the inaugural meeting Garcke was elected Chairman, Alfred Baynton, General Secretary and at the end of 1918, Major C J Murfitt joined the Board as the head of the engineering and operational side. During the negotiations it was agreed that the 74 vehicles the new company inherited would have red livery with East Kent painted on both sides in cream. The head office was to be in Station Road, Canterbury and the central garage would be at St Stephen’s, Canterbury. Although it was agreed that the 200 or so staff that EKRCC had inherited through the amalgamation would have standard uniforms, due to Wartime shortages they would keep the ones they had with the addition that the drivers would have Company oilskins and the conductors, hats and overcoats.

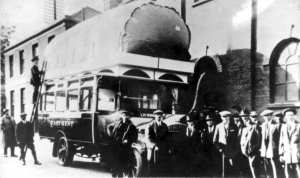

Although the new company had a large fleet of vehicles, many were in a poor condition such that only about 40 were serviceable. Nonetheless, once the news of the amalgamation was out, local councils expressed concern that the new company would infringe existing public transport routes that they operated. In response to this Kent County Council (KCC) issued a directive stating that EKRCC had to pay these councils either £10 per route mile per year or 1pence per bus mile for using water-bound roads; or 0.75pence per mile for using tarmac roads and 0.375pence for traversing concrete roads, which ever was the greater. Further, due to Wartime conditions, the new company was faced with fuel shortages and getting spare parts became increasingly difficult. Towards the end of the War petrol was so strictly rationed that EKRCC adapted some of the Tilling-Stevens buses to run on coal gas. The gas was stored in large bags on the roofs of the vehicles but were difficult to drive especially along the coastal roads. At Capel, west of Dover, on more than once occasion a bag blew off and out to sea! Added to this, since the start of the War it had been expected that it was the duty of every man, who was of military age to do his duty and fight for the country, which meant there was also a chronic shortage of experienced bus drivers.

From the mid 19th century, the town of Dover had rapidly expanded with new developments taking place along the valleys on the west side of the town. The ancient town centre, from the seafront across New Bridge, along Bench Street and King Street to Market Square then Cannon Street and Biggin Street, together with Charlton’s High Street and the London Road at Buckland, was thriving. So was the compact maritime Pier District, on the west side from the harbour to the cliffs, where Snargate Street was eclipsing Cannon Street and Biggin Street as Dover’s retail centre. To the east was Castle Street and the St James area comprising of buildings dating back to Tudor times, together making up a hotchpotch of housing, shops, offices and small factories. To enable the general public to get around were the horse-drawn omnibus services that operated on the mostly cobbled or untarred and dusty streets. One omnibus service, founded in 1876, was run by Frank Sneller (1855-1900) and based in Cherry Tree Avenue. There was also Back’s horse omnibus, which ran between the South Eastern Railway Station at Beach Street and Buckland Bridge, while another service was owned by Henry Alfred Smith, who operated from the Terminus Hotel in Beach Street and parts of town.

In 1894, Dover’s Electricity Company was established in Park Place and on 9 November 1895, the Corporation passed a resolution proposing an electric tramway. Authorisation was confirmed by the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No.1) Act of 1896 and the first tramway was officially opened on 6 September 1897. The 3foot 6inch (just over a metre) gauge track went from Market Square through the town centre for 3 miles and was laid within a year. All the trams were double-deckers and up to 1926 had open top decks. Further, each tram was fitted with a primitive cowcatcher type of guard to prevent anyone falling under the front of the vehicle and the seats were slatted reversibles by moving the backrest in the opposite direction to the way the tram was going – one such seat can be seen at the Dover Transport Museum. The tram service was popular from the outset as it was cheap, convenient, dependable and fast compared to horse-drawn vehicles. Dover ratepayers paid £27,700 for the system and the receipts in the first year were £7,478. The second year these increased to £9,882 when 4,673,124 passengers had travelled on Dover’s trams.

However, the Dover tram service only ran along the main streets of the town and to go further afield the choice for most was either the train or horse-drawn vehicles. On 26 June 1899 the Dover and East Kent Motor Bus Company, not EKRCC, addressed this problems when they started a two hourly bus service to the village of St Margaret’s, on the east side of Dover. Their vehicle, a Pioneer, was built by the Liquid Fuel Engineering Company of East Cowes, Isle of Wight and their first bus took two days to come from Cowes, having had an overnight stop in Hastings.

The Pioneer buses were very popular such that later Robert Morton & Son of Wishaw near Glasgow obtained a licence to build them. The first one to arrive in Dover had a steam engine with a marine type boiler that was fired by paraffin oil. The exhaust pipe was vertical and came out of the wooden roof looking like a chimney! The buses had two-stroke piston valves with cylinders 3inches and 6inches in diameter and a 5-inch stroke. The Pioneer could generate between 25 and 30 horse-power and was capable of going 25miles an hour (mph) but usually travelled at 18mph slowing down when going up hills. The steepest incline out of Dover was Castle Hill Road but as the buses improved in design, fully loaded they could tackle the hill with ease at about 4 mph.

East Kent Omnibus Company Pioneer used for the Dover – St Margaret’s – Deal service c1910. Dover Museum

The chairman of the East Kent Omnibus Company was Harry Stone, the Clerk of St Margaret’s Parish Council and the secretary was John Betridge. The buses were capable of carrying up to 28 passengers and had a wooden awning for the roof. However, the iron tyres made the ride uncomfortable and shortly after the service was started, to try and get round this, rubber was inserted between the wheel rims and the tyres. The terminus in St Margaret’s was at the top of Bay Hill and the journey took about 40minutes and was so successful it was later extended to Deal. The fare to St Margaret’s was 6pence, luggage being carried on the roof. Passengers were protected from the elements by a glass screen in winter and canvas curtains in the summer. The early Pioneers were divided into two compartments; behind the driver was one for smokers and had two cross-wooden benches seating 10 passengers. The rear compartment had benches down both sides. The driver was open to the elements with only overhead protection. In his cab there was a steering lever and at the side, the steam regulator and reversing gear.

On 19 September 1899 the Mayor of Dover, Sir William Crundall (1847-1934) organised Dover’s first motorcar exhibition which was held at Crabble Athletic Ground. One of the exhibits was a Pioneer and there were free rides on the bus. Unfortunately, the driver drove it off the track onto the grass where it sank almost up to the axles! Nonetheless, the bus was a success and eventually the East Kent Omnibus Company had three buses and one of the drivers was Herbert Salter. By 1902 Salter owned the company and he launched a service in Folkestone.

However, this ‘new fangled thing,’ as locals called the Pioneers did not go down well with the drivers of the horse-drawn vehicles. Complaints were such that Dover Rural Council ordered that drivers of horse-drawn vehicles had the right to stop the bus in order to drive past it in the opposite direction. The evening of 20 February 1909, saw the East Kent Omnibus Company’s worst accident when a party of sergeants based at the Castle were returning to their quarters on Western Heights. As the motor bus was going down Castle Hill Road, the brakes failed but the driver stopped the bus from careering down the steep bank at the side of the road, by crashing into a wall. He and some of the soldiers were injured and the bus was a write-off.

East Kent Road Car Company Leyland bus outside of Woodhams on Castle Street for the Dover – St Margaret’s Bay Service c1920. Dover Museum

When EKRCC came into operation in 1916, because of the War, Dover was under military rule and only authorised vehicles, including buses, car, lorries and railway companies could enter or leave the town. The East Kent Omnibus Company had the authority but they, like EKRCC were hit with wartime stringencies that was taking its toll on their vehicles. This came to a head in late December 1915, when a cliff fall blocked the South Eastern and Chatham Railway line at the Warren near Folkestone. After consultation with the Board of Trade, it was decided that the blockage could not be removed during the War and the state of the East Kent Omnibus Company vehicles were finding it impossible to meet the extra demand. When EKRCC came into fruition, Company Secretary, Alfred Baynton, negotiated with South Eastern Railway to replace the rail service by EKRCC buses.

The military refused to allow EKRCC vehicles to access the town and in consequence, if a passenger wanted to go by train to Folkestone from Dover they were obliged to go by way of Canterbury and the Elham Valley railway. It would appear that EKRCC came to a loose arrangement with the East Kent Omnibus Company to provide a joint service with the Omnibus taking passengers between Dover and Farthingloe and EKRCC between Farthingloe and Folkestone. Eventually, the military authorities capitulated and allowed EKRCC to run a service between Market Square and Folkestone for workers with special permits. The East Kent Omnibus Company carried on running the bus service from Market Square to St Margaret’s and to Deal until EKRCC took over initially using their vehicles.

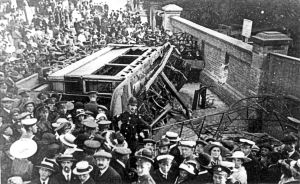

For travelling around Dover, the tram service remained popular but Sunday 19 August 1917 saw one of the worst tram accidents on record with 11 dead and 60 injured, many seriously. The Crabble Tram accident occurred at the bottom of the steep Crabble Road, River, where it crosses the River Dour. In 1915 the Ministry of War had issued a directive stating that tram driver vacancies were to be filled by soldiers who had been discharged from the Army on medical grounds. The driver of the tram that day, Albert Bissenden, fell into this category. He made a fateful error that was exacerbated by a catalogue of cost-saving measures going back to when the tram line to River was envisaged. Trooper Gunner, a former tram driver who was on board that day tried to stop the tram using his feet as emergency brakes. Sadly, he lost both his feet but was later awarded the Albert Medal for his actions. The official verdict into the accident was that ‘the deaths were caused by the tram-car running away and overturning and that the accident was caused through the error of judgement and inexperience of the driver of the car, and that the deceased’s met their deaths through misadventure.’ However, within all the reports, the underlying blame was firmly put onto Dover Corporation and due to inadequate insurance cover the town’s rates, in order to pay back money borrowed to meet compensation claims and repairs, were high.

War ended in November 1918, following which a regular bus service, operated by EKRCC, between Dover and Folkestone was introduced. In April a regular service between Dover and Canterbury was started and EKRCC rented from the council a designated area in the Market Square for a terminus. At the time, EKRCC was faced with fierce competition from former armed service drivers, who on being demobbed were setting up their own bus companies. Eventually, in East Kent, most of these companies that survived were absorbed by EKRCC. In 1921, the company introduced a regular coach service between Margate and London and started the predator take-overs or amalgamates with other companies. These included Pullman Motors, Silver Queen Motors, South Coast Motor Services and Cambrian Coaches, which had their headquarters in the old Oil Mills in Limekiln Street. Although the bus services were EKRCC ‘bread and butter,’ it was within the coach services where the profits lay. In 1932, under the influence of the London Coastal Coaches, a consortium of coach operators including EKRCC, the London Coach Station opened in Buckingham Palace Road, Victoria, London.

Daimler bus, one of 40 ordered c1919 and given new bodies in 1927 by Shorts of Rochester for the Dover – Canterbury service. LS

Following the War, Dover Corporation not only faced the huge costs associated with the Crabble Tram Accident, but due to military occupation and enemy action, their sources of revenue had been severely curtailed. To make matters worse, the country was sliding into an economic depression that was to last until the end of the decade. Hence, the philosophy of the town’s tram service was that of ‘make do and mend’, a preference for second-hand trams and new trams were only purchased when absolutely necessary. By 1922, the council were looking into the possibility of switching to what appeared to be cheaper trolley buses or making an arrangement with EKRCC to run buses in the town. However, the first was met with derision from the Chamber of Commerce and ordinary folk. While the second was met fierce resistance from within the council chamber as they wished to remain in control.

Although Dover council was desperately short of money on their own account, the government was providing infrastructure grants to reduce unemployment. It seemed to the council that if they looked to extend the tram service along the coast to St Margaret’s and possibly Deal, they would get one of these grants which could have long-term financial benefits for the town’s tram service. In 1920 the Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Light Railway Company had successfully applied to run a railway line from the Sea Front Railway at New Bridge to the Eastern Dockyard. Their idea was to connect this line with the old Pearsons railway track, extending it to St Margaret’s. From there, the proposed line would join the Southern Railway Dover-Deal railway line at Martin Mill. This had come to nothing but the council proposed to use the Parliamentary authority to construct a road / tram track along the agreed route but they were unable to get a government grant so the idea died. Nonetheless, they continued to look for other ways to secure finance to maintain the ailing tram service.

Having created a foothold in Dover with the designated terminus, EKRCC built on it by giving the contract to build 30 wood-frame 29-seater bus bodies to G S Palmer. The company was based at the corner of London Road and the then Union Road, Dover, with another factory in Cherry Tree Avenue. Then, in 1922, the Dover Gas Company moved its offices, workshops and showrooms from Russell Street to Northbrook House in Biggin Street – at the time of writing occupied by Halifax Building Society.

The Gas Company opened their new showrooms in 1923 and put their Russell Street premises up for auction. There they were purchased by EKRCC for £3,500 who demolished the Gas buildings and erected a bus garage on the site. Of interest, while excavating the foundation pits for the new building a number of Roman artefacts were found and these tied in with the already accumulating evidence that there had been a Roman harbour in the area. The bus garage opened the following year but Dover council were angry and in retaliation, EKRCC were required move their terminus from Market Square to Ladywell!

With a garage in Dover, EKRCC increased the regularity of buses to Folkestone but due to the narrowness of the road between the two towns, the buses had difficulty in passing other vehicles, including their own buses! This was exacerbated by the lack of footpaths, which put passengers at risk and although bus stops could be erected, there was little room for passengers to wait. Dover Corporation made it clear they had no money to pay for the road to be widened but did tell EKRCC that they were considering running a tram service between the two towns and were only waiting for Folkestone to agree. In fact the proposal never amounted to anything but EKRCC lost no time in badgering Kent County Council (KCC) to widen the road. KCC then acquired the land and widened the road from the Dover boundary at Farthingloe to the Folkestone boundary at the western end of Capel. Using unemployment grants KCC widened the road and EKRCC put in standing places for passengers by the bus stops.

In February 1928, Southern Railway submitted a Parliamentary Bill to enable the company to provide and work road vehicles in any district to which access is afforded by its system. This was for the conveyance by road of passengers, their luggage, goods and livestock, and to apply its funds for the purpose. The Bill also sought to enable Southern Railway to enter working relationships with Local Authorities, companies or persons owning or running road transport services. In 1918, Garcke had resigned his position as Managing Director of BAT in order to give him more time on his growing motorbus enterprises, which included the Maidstone & District Motor Services Ltd. However, retained his position on the Board – being elected chairman in 1923! In 1928, at the time the Southern Railway Bill was going through Parliament, Garcke was appointed a director of the BAT parent company, British Electric Traction Group (BET). He was also a member of the Council of the London and Provincial Omnibus Owners’ Association and under both ‘hats’ he took the leading role in the Parliamentary debates on the Bill.

The reason Southern Railway was seeking the changes in its Bill was due to rail transport being increasingly adversely affected by road transport and this was blamed on the bus companies. Garcke quickly assumed the leading role on behalf of the bus companies saying that there were about 11,000 bus companies in operation in the UK and that the number of passengers carried by the largest 45, in 1927 was 534,376,739. The number of staff employed by these 45 companies amounted to 850. Nonetheless, the effect on trains by buses was over exaggerated. The main culprits, he told the Parliamentary Select Committee examining the Bill, were private motorcars and motor bikes. The Omnibus Owners’ Association, he said, had carried out tests at various locations with frequent bus services, of which he gave details. These showed that on average 72% of road traffic on the particular routes were private vehicles. The lowest ratio was on the Dover-Folkestone road and this was due to the beautiful scenery through Farthingloe and Capel together with the low bus fares. On weekdays private transport amounted to 41% while on Sundays it was 53%. Guarke went on to say that since the advent of mass-production in the motor industry, the cost of motorcars had fallen to £100-£150 each and it is this that Southern Railway should be looking for the fall in railway travel.

Southern Railway’s Bill was enacted with the points that Garcke had made, taken on board. Following which, both sides negotiated a deal and in August 1928 Southern Railway had acquired 49% of EKRCC shares and the Bus Company came to an arrangement with the Post Office to carry parcels. These could be handed into any of EKRCC bus stations, to the conductor of a bus or to special appointed agents in towns and villages on the EKRCC routes. Charges were based on the single fare and the weight of the package, for which conductors carried a small spring weighing machine. In Dover, postal collecting boxes had been introduced on the trams in 1926 and following the parcel agreement, they were introduced on EKRCC buses. By which time in Dover, possibly due to pressure from Southern Railway, the Market Square terminus was reinstated and soon after premises was acquired to open an office on the west side of the Square.

Of interest, EKRCC parent company was British Electric Traction Company (BETC). Following the death of Richard Tilden Smith (1865-1929), who owned Tilmanstone Colliery, his interests were sold to the Anglo-French Investment Consolidation Ltd. This was part of the Drayton Group and affiliated to the Group was the British Electric Traction Company, the parent company of EKRCC.

EKRCC buses lined up in Market Square circa 1935 and note the EKRCC office sign on one of the buildings on the left – west side of Market Square. Bob Hollingsbee Collection, Dover Museum

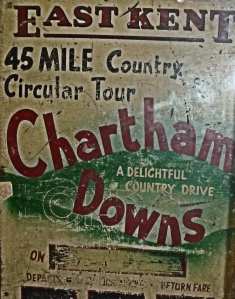

In 1929, EKRCC extended its operations to commercial charabanc services using single-decker coaches designed to take passengers on day-trip outings. The following year the wide sweeping Road Traffic Act (1930) affecting, both private and public road vehicles came into force. For public vehicles, the Act created Traffic Commissioners who were responsible for licensing and upholding new rules on the operation and the conduct of drivers, conductors and passengers on public service vehicles. The Act also introduced a 30-mile an hour speed restriction on buses and coaches, created a central regulation for coach services, and limited the hours of continuous driving. In 1931, EKRCC introduced their new Tilling Stevens B49 single-decker buses to Dover. Painted in the company’s colours of red and cream, the glossy buses lined up in Market Square making Dover’s trams look well past their sell-by-date. However, as the buses were petrol fuelled and without self-starters, the tram drivers took great delight in ridiculing bus drivers when they were swinging the starting handles to get the buses going!

1930 was a boom year for Dover, the shops were almost as successful as they had been before the War and folk from the surrounding villages were coming into Dover on buses to do their shopping. By this time EKRCC were running buses between Dover and Canterbury, Deal, Eythorne, Folkestone, Hythe, Ramsgate and St Margarets Bay, with stops in most of the hamlets and villages en route. Even Dover’s ageing tram service had seen their takings increase though the stock was looking distinctly worn out. Dover Corporation had been offered five top covered tram-cars by Birmingham & Midland Joint Committee for £800. Before making the decision, they looked at alternatives and found that the cost of a new tram would be about £1,500, while a ‘rail-less’ trolley would cost £2,500 but would be cheaper to run. The five tramcars option was taken up but the council was aware of a growing agitation against trams. The motorcar owners saw them as a nuisance, while cyclists were in constant danger of being thrown when their bicycle wheels had been caught in tram tracks. Some injured cyclists had threatened to sue but none, to date, had carried out the threat. This was a relief for by the time the second-hand trams arrived, Dover’s economy was rapidly following the national economy into a deep depression and the council cut back on insurance to save money.

By 1932 EKRCC’s takings, like Dover Corporation’s tram takings, were falling due to the fall in demand and particularly the holiday trade industry. Excursions to local destinations remained on offer and those that were taken tended to be by local folk who had previously taken short holidays outside of the district. Staff were laid off and as had happened after the War, some managed to get hold of vehicles, which they operated by undercutting EKRCC fares. Further cuts were imposed but care was taken not to make drivers redundant, instead a policy of driver’s collecting fares on single-decker buses was introduced and conductors were laid off.

In August 1932, a golf ball hit the windscreen of an EKRCC bus while it was passing the South Foreland Golf Club on the main Dover-Deal road, now the A258. The ball smashed the thick plate glass window and although flying glass cut a passenger, the driver was not hurt. The golfer apologised to the passengers and gave the injured passenger his golf ball as a memento of the occasion but the incident caused the bus company concern. This centred on the question of what would have happened if the driver had been hit and finding alternative windscreens that would offer greater protection became a priority. Although EKRCC had frozen wages and cut the number of employees, at the Annual General Meeting of December 1932, it was able to report that profits had increased and that they were able to pay a dividend of 6%!

The 1930 Road Traffic Act required new vehicles to have laminated glass windscreens – a process that had been introduced in the 1920s – and EKRCC had decided to replace older vehicles windscreens on an ‘as and when basis’. Following the golf-ball incident, all the buses had their windscreens changed and the company applied to the Traffic Commissioners for the authority to increase fares, part of which was to pay for the new windscreens. The following year, due to the continuing economic depression, the number of passengers carried by the company fell by 15.5% and even the amount paid in dividends were cut. However, by December 1934, the yearly net profits had increased to £41,503 against £26,168 for 1933 and everything was again auguring well.

The problem of public transport, in Dover had become acute and at the end of 1933, Dover council held a referendum on the proposal as to whether Parliamentary powers should be sought in order to replace the trams with a trolley bus system. The council expected that the idea would be fully endorsed and within the council chamber there was talk that the referendum was a waste of public money. On 6 January 1934, 37% of eligible Dover voters went to the polls and the result was:

For Trolley Buses: 976

Against Trolley Buses: 6,348

Majority Against Trolley Buses: 5,372

When the council recovered from the shock result, they set up a Transport Sub-Committee who, after much debate, drafted a Parliamentary Bill. This centred on taking up the Crabble Road to River terminus tram track and replace the service with council run petrol buses.

The number of Dover tram passengers in 1935 was 4,673,124 – the same as the joint first two years of operation – but the Transport Sub-Committee were seriously considering replacing trams with buses. Before parliamentary approval could be sought, another referendum was required. This was held in January 1936 but the turn out was even lower than the year before as only 25% of the electorate! Of those who voted:

In favour of Omnibuses: 2,743

Against Omnibuses: 2,200

Majority in Favour of Omnibuses: 543 or 2.75% of the voting population of Dover. These figures, without spelling out the percentage of the voting population, were incorporated into the Dover Parliamentary Bill to replace trams with a bus service. On 1 April 1936, the Borough boundary was extended up to the Plough inn on the Folkestone Road at Farthingloe. The Bill was sent to Parliament and on 4 April, EKRCC offered to provide a bus service in the Borough. Then, 18 days later, the full council rejected the offer.

In Parliament, due to the political climate of the time, the Bill became bogged down, so the council sought the advice of Alfred Baker, the General Manager of the Birmingham Corporation Transport Department. He looked into the problems Dover was facing and the alternatives and presented a report to the Council. EKRCC made another offer and Baker was authorised to open negotiations with Alfred Baynton, by this time the General Manager of EKRCC as well as Company Secretary. On 8 August 1936, an agreement was reached but was not made public until 20 September. This had the desired effect as the general principals had been reached and by the time it was made public, there was general acceptance.

The agreement gave EKRCC a 21-year lease to operate buses between Marine Station, Buckland and River and between Market Square and Maxton. The bus service was to take the slightly longer route to the Lord Warden Hotel by going over the viaduct instead of following the tram track by way of Strond Street and the Crosswall. The Maxton buses, would go as far as a designated turning point. The contract stated that EKRCC was to pay £3,000 towards the cost of laying concrete over the tram tracks and compensate tramway employees that they were unable to employ. After working expenses had been defrayed and a capitalisation charge of 3pence per bus mile, Dover Corporation was to receive approximately £2,055 per annum. This was based on 75% of the EKRCC profits gained within the Dover Borough boundary and inter-urban services that came within the Borough boundary regardless of boundary changes. Dover Corporation was not liable in the event of loss. Finally, the Corporation was to cease the running of trams at midnight on 31 December 1936.

The people of Dover were sad to see their beloved tram service go and when, on 31 December 1936 Mayor, Alderman George Norman, drove the ceremonial last tram to Buckland tram shed, at the bottom of Crabble Hill, the people lined the streets to wave goodbye. The town council had agreed to pay all their tram employees double for the last six days the service was in operation. On that evening, just before 23.30hrs, the last regular tram, Car No23, was driven by Vic Tutt onto the sleeper track at River.

The conductor on that service was Joe Harman, later a Dover historian, and he and Vic walked back to the Buckland tram shed. There, Joe telephoned the Electricity Works to cut the electricity off for the last time to Dover’s tramway system. Over the following days the old open-top cars were run out to the track at River and set on fire while the others were sold by contract. One of the former tram staff that were offered jobs by EKRCC was Joe Harman who was rapidly promoted to bus driver and given training as an engineer. Another was Alexander Vassey, who had been a Dover tram driver for years and as soon as his sons, Albert, Alex junior, Alfred and Arthur, were old enough they joined him. They were all transferred to EKRCC and were later joined by their younger brother Richard!

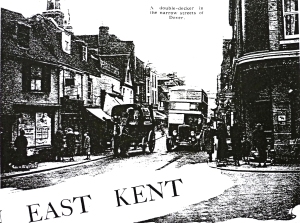

On taking over the control of Dover’s public transport, EKRCC introduced petrol driven double-deckers*. The buses had to be started by a handle and matches were used to set the throttle and choke. Because the Russell Street bus depot had been built for single-deckers, the roof was raised and the EKRCC leased the Crabble Hill tram shed for £122 a year from the council. However, training of tram drivers to drive buses had not been considered and on the first day the company took on former tram drivers, one was unable to negotiate the island in the middle of Market Square. At the time it had an arc light standard in the middle – this can be seen in the pictures above – and he demolished it! This was not the only accident that happened that day but none led to injuries.* The type of double-deckers used at this time in Dover is highly controversial: according to drivers at that time, they were patrol engined Lancet, reporters said that they were petrol engine Leyland TD4 or TD5s; According to modern day specialist researchers they were diesel engined Leylands.

East Kent Road Car Company TD4 double-decker on the narrow streets of Dover following winning the franchise from an article by Alfred Baynton in Bus & Coach magazine August 1937

Bus fares matched the tram fares and the workmen buses replaced workmen trams. These were on special buses and showed a ‘W’ on the service aperture. The workmen buses ran between Maxton and Buckland to Admiralty Pier and only workmen could use them. The journey cost 1penny regardless of the length. However, unlike trams, buses had to negotiate other traffic and it was found it difficult to keep to the printed timetables. The juggling of schedules in order to try to rectify this did not go down well with the passengers, and there was a growing demand to reinstate the trams. EKRCC, faced with the possibility of defaulting on the Dover contract, increased the number of buses on the service between Buckland and the town centre, but this was to the detriment of the Maxton service. At Maxton, passengers were encouraged to travel on the Dover- Folkestone buses but this led to overcrowding. The new bus services also had a negative effect on other road traffic users and one area of congestion was Biggin Street, Worthington Street, Priory Road and Priory Street. As Priory Street and Worthington Streets are parallel they were made one-way – going the opposite direction to each other – and this has been the case ever since.

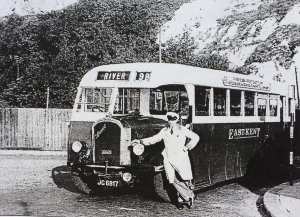

East Kent Road Car Company Dennis Lancet single-decker that were used on the River service while the new Crabble Road Bridge was being built and was then used for the Shepherdswell and Nonington services. Joe Harman collection

The service to River was initially a problem due to the steep Crabble Road, where the infamous Crabble tram accident had happened. The railway bridge crossing the Road was too low to allow a double-decker bus to go under. Therefore a contract was made between Dover Corporation, EKRCC and Southern Railway for a new, underline, railway bridge to be built. While this was going on Crabble Road was widened and curbed and petrol engined Dennis Lancet front-engine single-decker buses were used for the River service travelling along the Lower Road, River. The bridge was completed in 1937 when Leyland diesel engine double-deckers replaced the Lancet single-deckers which were redeployed on the recently inaugurated Shepherdswell and Nonington routes. To create a larger turning area in River, several houses were demolished and the concrete terminus was complete with a brick shelter and public lavatories. Initially the service to River ran from East Cliff to River via Maison Dieu Road but it was found more profitable to split the route into two separate services and run more buses.

Once the basic bus service was established, the council decided that other routes should be opened but EKRCC were not as keen as they were not seen as profitable. In the end, a trial service was run to Elms Vale and this proved profitable and so was followed by other services including one for Dover miners working at Tilmanstone Colliery. This, however, affected the East Kent Railway line so much that they cut the services between Shepherdswell and Tilmanstone to twice a day. EKRCC started a service to the Pilgrims Way area on what became the Buckland estate and to the Ropewalk on the fledgling Aycliffe estate. The bus to the Pilgrims Way area was once every half-hour and an hourly bus service was introduced to the Glenfield Road area. These new services, however, were at the expense of the Crabble Hill – Kearsney service, which had originally been quarter-hourly but was cut to an hourly service.

When EKRCC replaced the Dover tram service, there was another independent East Kent tram service in operation. This was the Isle of Thanet Electric Tramway run by a private company, the main owner of which was the Isle of Thanet Electric Supply Company (ITESC). The Isle of Thanet Electric Tramway was partly financed by Margate, Ramsgate and Broadstairs councils and the Company had negotiated with the three councils to replace trams with buses. The deal had almost been completed when the three councils’ changed their mind and gave the contract to EKRCC. With their hands forced, in August 1936, ITESC sold their Tramway operation to EKRCC for £135,000. However, EKRCC were obliged to accept the same terms and conditions previously negotiated between the three councils and ITESC before the Traffic Commissioners would give their approval. This, the Traffic Commissioners were slow to do and EKRCC were forced to run the services as an agency until midnight on 24 March 1937, when permission to take over came into operation.

Once this was achieved, EKRCC had the monopoly of the East Kent public road transport, which was the main reason for the delay by the Traffic Commissioners. Then, within less than a month of EKRCC formerly taking over there was a national strike by members of the Transport and General Workers Union in bus companies that recognised the Union. This was about pay and working conditions but at the time, EKRCC did not recognise the Union but some of the workers of the newly taken over Thanet depot were members. On 21 April, these workers issued a statement giving EKRCC 48hours to recognise the Union and open negotiations for a settlement. Without confrontation, Alfred Baynton, on behalf of EKRCC, agreed and successful negotiations took place.

A Manchester bus being craned aboard the Townsend cross-Channel ferry Forde, in the Camber, Eastern Dockyard 1930s. Dover Museum

The negotiated settlement was implemented throughout the EKRCC but regardless of this and the costs of taking over the Dover and Thanet operations, 1937 was a profitable year. The main source of this finance came in the three-month summer period when holidaymakers from the English industrial heartland’s descended on East Kent – the Garden of England – as the area was known at the time. Large percentages of the holidaymakers were either directly or indirectly employed in the armament and associated industries that had been expanding over the previous three years. To meet this need, EKRCC invested in some 60 new vehicles and started running services to the Continent. For this, EKRCC used Captain Stuart Townsend’s vehicle-carrying cross-Channel ship Forde between Dover Eastern Dockyard and Calais on which the buses were already being craned on and off.

By the end of 1938, wage costs were eating into profits of many bus companies and there was talk of rationalisation or even nationalisation. Neither of these appealed to Sidney Garcke, EKRCC’s long standing Chairman, who argued that economies of scale were finite and EKRCC had reached its optimum size and consequently it was not faced with such problems. At the time, EKRCC’s area stretched from the mouth of the Thames round the Kent coast to Hastings in Sussex, plus 11 large Kent towns not on the coast plus rural services in-between. EKRCC’s gross revenue for the year ending September 1938 was £700,000 but taxes amounted to £108,000. The number of buses owned was 549 and the number of passengers carried was 46million.

Garcke again emphasised that the most profitable time was during the three summer months and it was the revenue from the holiday traffic that sustained the company for the remainder of the year. Nonetheless, at the Annual General meeting a number of shareholders complained that the dividend was merely 6% of the net profits, when they expected more. Garcke responded saying that wages accounted for 40% of the net takings equalling £236,800. All of the remaining revenue, except for 6% of the net equalling £35,520 that went in dividends, went on running costs, overheads and vehicle maintenance and new buses – which was what the company was all about! This, he added, amounted to £319,680!

World War II (1939-1945) started on 3 September 1939 when, during the normal course of events holiday traffic would be buoyant until the end of the month. Earlier in the year, EKRCC had ordered a fleet of Leyland Tiger TS8 32-seater touring coaches with Park Royal bodywork and rear entrances. However, because of the declaration, trade came to an abrupt halt as holidaymakers fled the county. Nonetheless, EKRCC were optimistic comparing the situation with World War I when, despite the battles ranging on the Continent just across the Channel, holiday makers still came to East Kent. This time, so safe was East Kent seen by the authorities that before the end of September thousands of children were evacuated from London to the area, which created a demand for bus travel. By Christmas 1939, as the War was still not directly affecting the UK, many of the evacuated children returned to the Capital and EKRCC joined East Kent holiday resorts in a publicity drive. This was to persuade the holidaymakers to return for the summer of 1940 and a picture of a new Tiger coaches featured in an advert.

East Kent Road Car Company Leyland Tiger TS8 ordered in 1938 the first and only one to arrive was BFN 797 in March 1940 (Phil Drake). LS

This period, in the UK, was called the Phoney War, nonetheless there were shortages. By the end of September 1939, fuel rationing had been introduced and this adversely affected the number of EKRCC bus services. On roads, a maximum speed of 20mph in built-up areas was imposed which meant that the bus timetables had to be rewritten. These two aspects combined to make EKRCC have more buses then they needed and the company came to an arrangement with the Ministry of Health, to lease some 30 Leyland TS7 buses. These buses were converted into ambulances and manned by EKRCC first aid trained drivers. EKRCC was expected to maintain these ambulance/buses but it was generally felt that as the War would remain at a distance, they would not be used as ambulances. Hence, the adaptations were undertaken such that they could be easily returned to normal usage. In March 1940, the first of the Tiger coaches, with the registration BFN 797 arrived for the summer season, it was the only one out of the ordered fleet to arrive.

At the outbreak of War, Dover, as in World War I, became a military zone with the title, Fortress Dover. By Christmas, there was an influx of military and naval personnel which created an unforeseen demand on EKRCC that lasted until the early spring of 1940. At the same time, early bookings by potential holiday makers made the coming season look very promising. On the Continent, the German forces, were employing blitzkrieg tactics – attacking with a dense force of parachuted-armed soldiers quickly followed by armoured, motorised infantry with close air support. Country after country was falling like dominoes and refugees from the Continent were arriving at Folkestone on cross-Channel ferries in increasing numbers. Fortress Dover had ceased to be a commercial port nonetheless, many refugees arrived in Dover on a variety of seagoing vessels. These berthed by the Prince of Wales Pier and from there the refugees were taken by EKRCC buses to the then Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu, for documentation and interrogation. At the time, there was a fear of German spies and a Fifth Column – people who were working with the enemy to undermine the UK – entering the country.

As German forces were rapidly moving through France, on 10 May 1940 an All Party Coalition was formed in Britain with Winston Churchill (1874-1965) as Prime Minister (1940-1945) and Anthony Eden (1897-1977) as the Secretary of State for War (May-December 1940). By 21 May, although putting up desperate resistance, thousands of Allied troops, mainly comprising of the British Expeditionary Force, were cornered at the port of Dunkirk. Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945), who had served with the Dover Patrol in World War I, was in command of Fortress Dover and in charge of the Evacuation of Dunkirk. On Sunday 26 May Operation Dynamo was put into action when, under Ramsay’s direction, a fleet of 222 British naval vessels and 665 other craft, known later as the Little Ships, went to the rescue of the beleaguered troops.

The Dunkirk Evacuation continued over the following nine days. Lining up in Snargate Street, were EKRCC buses that took whole battalions of soldiers to destinations in Kent while some 327 trains took survivors to locations throughout the country. Over the nine days of the Evacuation, 180,982 men were landed at Dover and EKRCC provided 250 vehicles, including those converted into ambulances, fully manned for 24/7. These were located at Dover, Folkestone, Margate and Ramsgate with 50 held at Canterbury to meet contingency needs. Not only were the buses driven by EKRCC drivers but also by other members of staff to give the drivers time to snatch meals and sleep.

Following the Dunkirk Evacuation the UK seriously prepared itself for wartime conditions. EKRCC timetables were cut and over 100 buses and their drivers were seconded to government projects with a large contingency attached to the Army replacing transport lost before and during the Dunkirk Evacuation on the Continent. Children from London that had remained in the County were sent, along with children from East Kent, to Wales for their safety. They all travelled by train from the main railway stations but EKRCC buses were used to collect the children from a variety of locations to take them to the stations. In preparation against invasion EKRCC buses were also used to take armies of workmen and Home Guards to erect a variety of defences.

The blackout had been imposed at the beginning of the War but it was not until the fall of Dunkirk that it was taken seriously. For EKRCC drivers, during the hours of darkness, the roads were extremely hazardous. There was no street lighting and house lights were hidden behind blackout curtains. The bus headlights were masked so that they could not be seen from the air, nor did they light up the road ahead as this would have enabled the enemy to follow them. The interiors of buses were lit with dim blue lights in order to make them difficult to be seen. During daylight hours buses were vulnerable to air-attack and to make them less visible, they were repainted grey with white painted edges on the front wings. The latter was to enable pedestrians and road users to see them.

In the event of an air raid, bus crews were instructed to go to the nearest shelter and wait there until the all clear was sounded. All EKRCC bus-crews carried their personal documentation and passes and for those members of staff that were likely to come to Dover or lived in the town, they were given special passes issued by the military. All passengers that wanted to enter or leave the town were required to have a special pass. The taking of photographs was banned throughout the East Kent area, so only official and approved photographs remain.

10 July 1940 saw the start of the Battle of Britain – the prolonged aerial conflict for the control of the skies above the Channel and South Eastern England. This was between the Luftwaffe (the German Air Force) and the Royal Air Force. Both EKRCC St Stephen’s garage in Canterbury and the offices at Horsebridge, Whitstable took a direct hit. Although, no one was severely hurt, buses and the buildings were badly damaged. The Battle lasted until 31 October 1940 and in May, Anthony Eden, had set up the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV) – later renamed the Home Guard. During the summer, EKRCC set up platoons under the heading of Home Guard Transport Column and included a Dover platoon. One of their main tasks was the defence of EKRCC’s premises and vehicles but they also worked closely with other companies of Home Guards and mainly drove Tilling-Stevens vehicles. Gas masks were issued to the population and although people were suppose to always have one with them, spare ones were carried on the EKRCC buses.

The failure of the previously expected profits from holiday traffic hit EKRCC hard and to raise revenue they hired vehicles to other bus companies at £2 a day. They also leased buses and their drivers to the government to take armament and aircraft workers to and from their factories. EKRCC buses and drivers were used to transport construction workers to locations that had been hit during bombing and the later shell attacks. EKRCC buses and drivers were also used to transport the Entertainment’s National Service Association -ENSA – members to entertain troops. At times, the provision of buses and drivers was gratis, particularly to the armed services based in Fortress Dover when they were redeployed, at short notice, to other areas. By the end of EKRCC’s financial year in September 1940, the company net profits had fallen from £58,214 for the year 1938-1939 to £22,248 and for the first year since 1916, the company did not pay out any dividends. At the AGM, held in December, Sidney Garcke, was full of praise for the staff, particularly the drivers and conductors in the east of EKRCC area, saying that they were constantly running the gauntlet. He went on to say that ‘All concerned with the enterprise, from the most senior to the most junior; from those who have been with us since the beginning to those who have joined us lately, deserved the praise and gratitude of the public.’

1941 was the silver jubilee year of the founding of EKRCC and Sidney Garcke was still the Chairman. In the New Years Honours of that year, he was created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire or CBE. The company accounts showed an increase in revenues of 28% over the previous year due to the presence of military in the area and the leasing of buses. However, the buses were depreciating, while others were victims of air raids. The lack of new buses being manufactured meant that they could not be replaced. Eventually, in order to rectify this, EKRCC set aside the assumed costs for replacements. This reduced the Excess Profits Tax and the refund was paid into the appropriate account. By 7 May 1941, the Dover area was nicknamed Hell Fire Corner and during shelling, one exploded in Market Square overturning and severely damaging an EKRCC bus. The driver and conductor were injured, mainly from flying glass and the company offered the forty-one EKRCC staff living in Dover relocation. The new homes were in a village some miles from the East Kent coast and although the company offered to pay all expenses, only two took up the offer. This, reporters and journalists in other parts of the country wrote, proved the stories emanating East Kent were fabricated. In August, one such journalist was sent to the area for twenty-four hours to ‘find and report the truth.’

He arrived from London at a Canterbury railway station and from there caught an EKRCC bus to Dover. It had been reported that on the steep roads into and out of Dover,buses, on clear days, were at the most vulnerable to attacks from across the Channel. The day the journalist arrived, the weather was clear and sunny, all was quiet and the bus safely reached Buckland Bridge. En route, it had been stopped on several times at checkpoints, which the reporter found both tedious and a waste of time and could not see the point of having to have a special pass to come into Dover.

As the bus wended its way along Buckland’s London Road, the reporter noted the curtained windows of the houses and cottages, children on the streets, babies in prams and shops selling flowers. By the time the bus reached the Market Square, although he had seen gaps where buildings had once stood, the boarded up windows and the tile-less roofs, the reporter was firmly convinced of the exaggeration of Dover’s situation. He checked into a bed and breakfast in Biggin Street and spent the evening at Dover’s Hippodrome theatre on Snargate Street. There, he mixed with service personnel based in Dover, locals and members of the cast in the bar. They were all cheerful and made light of the reports on what was happening to the town. During the second half of the show the sirens were sounded but the audience did not seem perturbed, which totally convinced the journalist of the sham.

World War II – Snargate Street, note the East Kent Road Car Company bus on the right. Dover Transport Museum

The night was quiet and the next day the journalist walked round the town and began to see the extent that Dover was under constant attack from bombs and shells. He spoke to some children playing on a bombsite and they told him that they had been evacuated to Wales but missed their homes and had come back but that there were no schools. He then met up with an EKRCC conductress and asked her why she was staying in the town. She replied that she and her young son, who had returned from Wales, had lived in Dover all their lives and ‘would not leave it for anything.’ She went on to say that her husband was ‘in the Persian Gulf and I am sure that he would wish to have the home fires burning!’ The journalist spoke to others and later he wrote of his first impressions and how they changed when he realised the extent of attempts that the people of Dover were making in order to retain a semblance of ‘normality.’ He took the EKRCC bus back to Canterbury and as it climbed up Crabble Hill, he heard the sound of shells exploding nearby. One of the explosions shook the bus, to which the bus conductoress casually remarked, ‘We left just in time!

In August 1943, another journalist took the same journey by which time it was generally acknowledged that EKRCC was the only Bus Company in the country that ran services under a permanent emergency. The journalist had been told that three of the company offices had been hit and three of the garages blown up while the rest had been damaged to a greater or lesser extent. He had also been told that two old Daimler double-deckers had been turned into mobile offices and another into a staff mobile canteen. Mobile fare stages had become the norm, as there was ‘little point in making them permanent as no one knows when it will be blown up!’ In Canterbury the journalist had been told that some 14 members of EKRCC staff had been killed and thrice as many wounded by shellfire, bombs and machine-gun on the roads that traverse East Kent.

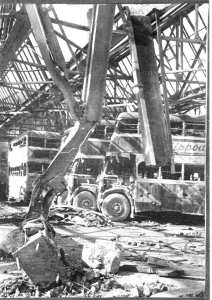

As his bus from Canterbury arrived in Dover, the journalist saw evidence of the continual shelling and bombing everywhere yet the attitude of Dover people had hardly changed. The only major difference was the children were not so much in evidence on the bombsites as a semblance of schooling had been introduced in the intervening period. On arrival in Market Square, he noted the bombed-out EKRCC office and the other wrecked buildings and made his way to Dover’s Russell Street bus garage and stood aghast looking at the devastation. The derelict building was empty except for a bus being refuelled by the driver who told him that ‘luckily the tanks had remained intact and that they were still being used for company buses.’

East Kent Road Car Company Russell Street garage Dover following bombing on 23 March 1942. Dover Museum

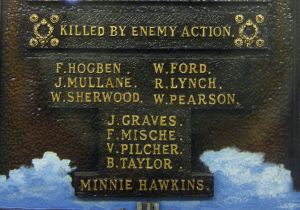

When asked what had happened to the garage, the driver told him that on the moonlit evening of 23 March 1942, the Dover EKRCC manager Brian Taylor was finishing off his work at the garage when at 19.15hours he heard the sirens. The staff were making their way to the air-raid shelter in the basement of the building but as Taylor was leaving his office, he received a ‘phone call saying that the EKRCC office in Market Square had been hit and that it was believed there were dead and injured. Taylor was a Lieutenant in the Home Guard and, of his staff, that members who were at the garage that evening were William Ford, Robert Lynch, Frederick Mische, Victor Pilcher and Walter Sherwood. Taylor, the driver said, would have had no doubt that they would go and help. But before Taylor had chance to leave his office and while bus conductress, Minnie Hawkins was still on her way to the shelter, a German Junker’s JU88 dropped it’s armour-piercing bomb onto the garage. The bomb penetrated the roof of the garage and the air-raid shelter below.

The Civil Defence, soldiers and locals were quick on the scene and on clearing debris, they found Minnie Hawkins just outside the shelter, dead. Soon doctors and nurses and more help arrived and a shuttle service of ambulances was arranged to take victims to hospital. Victor Pilcher, who had been blown out of the shelter through a gap as the roof fell in, was found still alive but badly injured. He died four days later from internal injuries at the Casualty Hospital, now Buckland Hospital. The shelter was located and the rescue squad managed to get into it through the hole in the roof. However, it had almost filled up with water from a burst water main and this hampered rescue attempts. Eventually EKRCC Inspector William Pearson was hauled through the hole. He too was dead and his body was followed by those of William Ford, Frederick Hogben, Robert Lynch, Walter Sherwood and Frederick Mische who was an ARP Ambulance driver as well as being a member of the Home Guard. At the funerals, members of the Home Guard were bearers of their colleagues’ coffins and representatives of the Transport and General Workers’ Union attended.

The reported devastation of the EKRCC office in Market Square turned out to be correct and Jack Graves, a bus inspector, was killed. The office had been in the same block as the Conservative Carlton Club on the west side of Market Square, which had taken the hit and where four were killed. Outside, Private Alan Bowles, a 20 year-old soldier in the Buffs, had died under falling masonry and Ella Dixon, age 17 of East Langdon, was killed while sheltering in a doorway. The wife of the club steward was buried under the club’s debris for 13hours before she was finally rescued. Following the War, a Memorial was erected at the rebuilt Russell Street bus garage, which also included others connected with EKRCC who were killed during the War. Prior to garage demolition, the Memorial was removed to the Dover Transport Museum, Old Park, Whitfield where it can be seen.

The EKRCC employees were:

William George Ford age 29 of 82 Longfied Road – killed 23.03.1942

John Graves age 49 of 10, Shipmans Way – killed 23.03.1942

Minnie Gladys Hawkins age 27 of 68 Oswald Road – killed 23.03.1942

Frederick James Hogben age 55 of 25 Buckland Avenue – killed 23.03.1942

Robert Magnus Lynch age 37 of 43 Elms Vale Road – killed 23.03.1942

Frederick Charles Mische age 45 of 11 Winchelsea Street – killed 23.03.1942

John Mullane age 64 of 41 Albany Place – killed 07.06.1944

William Pearson age 56 of 140 Mayfield Avenue – killed 23.03.1942

Victor William Pilcher age 43 of 2 Knights Way – died from injuries 27.03.1942

Walter Sidney Sherwood age 31 of 7 Underdown Road – killed 23.03.1942

Brian Taylor age 32 of Court Cottage, Kearsney – killed 23.03.1942

Other Dover EKRCC employees killed during World War II include,

Flight Officer A Bourner,

Flight Sergeant Cadman,

AP Clarke,

Sergeant Griggs,

Private A Morley,

Private J Pay

J Redpath

During his time in East Kent, the journalist no doubt reported that on 31 May 1942, the EKRCC headquarters in Station Road, Canterbury was attacked and in the same raid, the company’s Canterbury garage and body shops were destroyed. In addition, during an afternoon in October 1942 a bus travelling on the Herne Bay / Canterbury Road, near Sturry was attacked by several aeroplanes using machine guns. The conductress managed to get all the passengers out and into a ditch for safety. She then ran back to the bus to see why the driver had not joined them to find him hanging over the wheel, shot through the heart. On the same afternoon, another bus was leaving Canterbury when two bombs exploded on either side. The conductress and nine passengers were killed. Although injured the driver managed to pull out the remaining 36 passengers from the badly wrecked bus and took them to a shelter.

The journalist had planned to take a bus from Dover to Ramsgate across what he had been told was the most dangerous of all of EKRCC routes, the Downs. He was told that these buses only ran if there was a driver willing to take the bus and if a conductress went along, that was her decision. For this reason there was no fixed time schedule and he was warned that there was no knowing when the Germans might swoop out of the clouds and attack the bus. Eventually, a bus left for Ramsgate and the journalist managed to get on board. He later wrote of the ‘white scars in the harvest fields alongside the road,’ which the conductress told him that huge German shells had quarried them out of the chalk. When they arrived at St Peter’s depot in Thanet, the Dover driver, Harry Howland, told the journalist that the windows of his cab had been blown out several times and that ‘you never know when you look out of your cab when you will see a yellow nosed plane with a couple of Jerries looking at you!’ He went on to say that on one day, the Germans dropped 187 sticks of bombs on Dover between 15.00hrs in the afternoon and 21.00hours at night. ‘But,’ he added ‘Spitfires shot down 17 big machines and the bus company’s staff stood at the doorways and watched them come down … we never turned a wheel!’

At the St Peter’s depot in Thanet, the journalist met Driver Thaxted, who told him that on one wet afternoon earlier that year a German machine had flown low over the depot. ‘It was so low that you could see the raindrops sweeping off the wings.’ It dropped two bombs and one wrecked the wall of the depot while the other skidded along the floor almost to Thaxted’s feet but he got out in time before it exploded! The depot was badly damaged and a temporary office had been set up in an old bus. In answer to the journalist’s question about what had happened to the Canterbury operations, Thaxted told him that many of the clerical staff had previously been dispersed to scattered locations, including Lydden, where Dover’s clerical staff had been moved. Buses that could be repaired were sent to Faversham and that EKRCC had taken over Alcroft Grange on Tyler Hill on the outskirts of Canterbury as temporary headquarters. Before he left Canterbury for London, he met Alfred Baynton, the long term General Manager and Company Secretary. He was in charge of co-ordinating all of the EKRCC’s scattered premises, dealing with the dead and injured staff which included making many of the arrangements as well as the general day to day running of the company.

As most of the company’s bus repairs had been carried out at Canterbury following the attack, a temporary body shop was set up at Seabrook, near Folkestone until better arrangements were made. At the time, Seabrook was being used as a temporary garage for the Dover operation until they were moved to the tram shed at the bottom of Crabble Hill later in 1942. The history of the Seabrook garage history goes back to 1872, when South Eastern Railway had envisage opening a line to Folkestone Harbour via Sandgate from the Sandling Junction. However, due to adverse pressure from locals, the line was not laid beyond the Seabrook station. During the interwar period, EKRCC bought the station and built a garage across the platforms. Following the Dunkirk Evacuation, as it was on the coast, the fuel tanks were filled with sand to avoid explosion. This meant that when the depot was commandeered for repairs the fuel had to be kept in a tank wagon!

Following the bombing of the bus garage, the shore based establishment HMS Lynx moved into the cellars and they became the headquarters of Minesweepers and Patrol Craft personnel. HMS Lynx was set up in September 1939 and paid off in 1946 and the commanding officer was accommodated at the nearby former Fremlins brewery!

Local historian, Joe Harman, worked for Dover EKRCC and in his reminiscences of the War years (Bygone Kent Vol 12 No3) he tells us that following a near miss of the Buckland Tram shed by enemy attack on 25 October 1943, buses tended to be parked overnight at the River Terminus. However, on cold mornings it was difficult to get them running and during severe frosts it was necessary to drain the radiators and cylinder blocks overnight. To get round the problem of starting the buses the next morning, within the fleet were some Tilling-Stevens buses and these had 12-gallon radiators. In the morning, the staff draped warmed sacks over one of the Tilling-Stevens radiators, set the throttle and using cold water from an indoor toilet and the emergency fire tank in the radiator, cranked the bus into life. As the engine ran, they drained up to two gallons of water at a time out of the Tilling-Stevens drain tap and used this water in the other buses radiators!

Chairman of EKRCC, Garcke, back in 1913, was one of the principle founders of the Provincial Omnibus Owners’ Association and in 1943, the Association became part of the newly formed Public Transport Association. Like many other bus companies by the end of that year, EKRCC was desperately short of vehicles. Out of the pre-war fleet of 549, the company had lost 208 buses. The Association put pressure on the Ministry of Supply, to allow new buses to be built and eventually specifications for a bus was drawn up. These were ubiquitous ‘utility’ single and double-deckers, built to a design that required the minimum amount of materials, skills and costs. The chassis was based on the successful pre-war Arab design, made by Guy Motors of Fallings Park, Wolverhampton. However, due to shortages, the lighter aluminium of the 1930s, was replaced with heavier metals. The engines were built by L. Gardner and Sons of Barton Works, Patricroft, Manchester and were either of the 5LW or 6LW range. Although, generally, the bodies were built by various manufacturers and consequently each batch could differ, EKRCC were lucky in that most of the fleet of 97 buses they ordered were made by Charles Roe of Leeds or Metro Cammell Weymann. The rest were hybrids built by EKRCC at Canterbury. As for the passenger seating, moquette cushions gave way to wooden slats.

Castle Street following the last shell to hit and cause material damage on Dover. This was on Tuesday 26 September 1944. Kent Messenger. Dover Library

June 1944 saw D-Day and the Normandy landings. As the Allies moved up the coast of northern France, the shelling of Dover became increasingly ferocious until the last shell to cause material damage hit Castle Street on the evening of 26 September. Once the realisation that the four years of bombardment had ended in Dover, a temporary EKRCC terminus opened in Pencester Road on a bombsite. One of the old Daimler buses was brought from Thanet to serve as a mobile office and another was brought in to serve as a staff canteen. To help to kit it out Dover’s Home Guard loaned its field kitchen.

Part II of the East Kent Road Car Company tells the story from 1945.

Presented: 26 October 2016

Further information:

Dover Transport Museum: dovertransportmuseum.org.uk

Home Front Bus Tours: info@homefrontbus.org.uk