The Oil Mills, on Limekiln Street in the Pier District of Dover, made seed cake for cattle and oil mainly for domestic use. The factory backed onto the cliffs within which the old caves excavated for lime making had been considerably enlarged and used as part of the complex. However, with the building of the railway line from Priory Station, on Folkestone Road to the then Harbour Station by what are now Western Docks, by the London Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) in 1861, the size of the factory was significantly reduced. The Oil Mills were put on the market and eventually acquired by the large Oil Seed Crushing Company, the chairman of which was R Hesketh Jones.

Shortly after, in January 1866, the 455-ton barque, Beautiful Star, carrying a cargo of cottonseed from Alexander to Dover was badly damaged in the Bay during heavy weather. A crewman was lost overboard and much of the cargo was a write off. Nonetheless, in August of that year, the company reported that after paying out 14% dividends, £6,638 had been added to the reserve fund. In 1869, they paid out 28 shillings (£1.40p) a share equivalent to 3% per annum and the ‘successful’ factory was providing work both directly and indirectly, for over 1,000 locals.

However, the 19th centuries notorious economic booms and slumps ensured that the good times were not going to last. Trade started to deteriorate but the price oil seeds continued to rise so wages were cut. Then, in 1874, the mills were subjected to another devastating fire and the factory had again to be rebuilt. Trade quickly picked up and the following year ships from the East Indies, Argentina and Russia were unloading linseed and cotton seed in the newly opened Granville Dock. Four years later there was another slump resulting in wage cuts and lay-offs. This had a major knock-on effect throughout Dover. Not long after the economy picked up and although the Company was involved in an expensive lawsuit, they were able to pay dividends.

In 1888, the firm published a description on how they made seed cake. There were three identical sets of processor machines with powerful rollers into which the seeds were fed and the casings cracked. From the rollers, the cracked seeds were put into large pans and grounded by stones weighing five tons each. The result was a fine dark powder that was caught up in an endless band of cup elevators that deposited their contents into large vats, or more correctly ‘steam kettles’, which were 14-feet (4.2 metres) from the ground. The seeds were then heated and allowed to fall onto large circular iron tables where they were pressed using devices patented by the company.

Once pressed, the seed casings were pressed into ‘cakes’ on which ‘Dover Invicta’ was stamped. The output that year was 90-tons every 24-hours and the cakes were mainly used for cattle feed. Most were sent by ship to London for distribution within the UK and for exporting to France, Germany, Sweden and the West Indies. The factory refine oil and to reduce the risk of fire, this was inside the caves at the back of the mill. In those days, refined linseed oil was used for painting and industrial purposes. Cotton oil had domestic uses particularly as a substitute for olive oil and rapeseed oil was used in soap, lubrication and candle making. During the refining process cottonseed oil produced stearine, used to make composite candles and pitch that was exported to the USA.

The company operated two large steam engines providing 350-horsepower, two smaller engines and five boilers. These were all housed in the caves that were estimated to have a storage capacity for 3,000-tons of coal. There was also a series of tanks capable of receiving 2,000 tons of oil and a reservoir with the capacity for 500,000 gallons of water. However, instability in the Company’s boardroom plus the high price of coal in Dover, brought about by coal dues that were paid to the council for coal passing through the town, combined to the mills closing in 1889. This had a devastating effect on the town’s economy.

Three years later, in 1892, the buildings were sold to businessmen Temple Hillyard Soanes and Frederick Garrard (1861-1944). Both were members of the Baltic Exchange and Frederick Garrard was the manager of the Produce Brokers’ Company and vice-chairman of the Oil Seeds Association. The latter was an oligopoly of four companies that ruled the trade and included the Oil Seed Crushing Company.

In 1894, the oligopoly was involved in a complex High Court case appertained to fraudulent misrepresentation made by Soanes, Garrard and a George Emanuel Scaramanga, amongst others. It would appear, from the law report, that oil seeds were not worth as much as they made out and serious losses were being incurred by buyers. Of interest, in 1916, Frederick Garrard was elected the chairman of the Baltic Exchange.

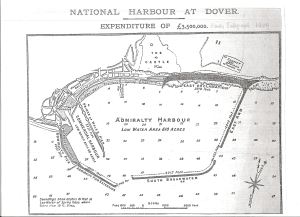

While this was going on, the Mills were leased to S Pearson and Son Ltd who had won the Admiralty contract to build the harbour we see today. They renovated the Mills creating 25 rooms to accommodate 200 workers involved in building Admiralty Harbour. Work on the new harbour started on 5 April 1898 and the council granted a common lodging house licence for the Mills, renamed ‘Admiralty Harbour Dwellings’. The Admiralty Harbour was opened on 15 October 1909 by which time the use of the Oil Mills had changed. On 10 July 1906, fire had destroyed Wiggins Teape’s Crabble Paper Mill and while rebuilding was going on, the Oil Mills were rented and utilised by the company.

With the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) in August 1914, the Mills were commandeered for use as an air-raid shelter. The ferro-concrete floors, which were sandbagged, were seen as ideal protection but folk felt safer in the caves. In consequence, the buildings were used by military and naval personnel as rest barracks. As for the caves, wooden benches were fixed along the walls and separate caves were set apart for men and women. Electric lighting was installed and volunteers with a detachment of soldiers kept order. At the end of the war, soldiers awaiting demobilisation were billeted at the Mills but on Saturday 4 January 1919, fed-up with waiting, they marched on the Town Hall demanding to be allowed to go home. Addressed by the Headquarters Officers they quietened down and the demobilisation hurried.

Throughout the inter-war period, the Mills and caves were put to a variety of uses, from the headquarters for Cambrian Coaches to a mushroom farm in the caves, run by a Mr Stevens. In 1927, Temple Hillyard Soanes and Frederick Garrard sold part of the complex to A.M. Kemp-Gee Ltd who paid for the holdings using a loan from Midland bank. Three years later Kemp-Gee defaulted and the Mills were put on the market again. Mr Stevens’ mushroom growing company bought part of the complex in 1934 and the remainder was purchased by Cumbria Motor Coach Co. for a garage. This they developed into a motor coach works until they were bought out by East Kent Road Car Company, when the site was let to other firms.

In 1937, with the threat of hostilities, the Council commandeered the Oil Mill caves but when the crisis ebbed, they handed them back. Mr Stevens received some compensation for the damage done to his mushroom growing business but not satisfied the case went to court. An out of court settlement was reached but later that year the Oil Mill caves were again requisitioned. World War II (1939-1945) began on 3 September 1939 and three days later the military issued a notice stating that the caves would not be used as a public shelter. The Mills and caves became a command post, Royal Navy hospital – flying a white ensign, transit camp and an air raid shelter for personnel from HMS Wasp based at Lord Warden Hotel (now House). The incumbents, including Mr Stevens, were forced to move out.

The Mills housed the town’s back up Air Raid Precautions (ARP) control station – a civil-defence organisation from 1924 to 1946. Nearby, on Friday 25 October 1940, ambulance man Victor Abbot was sitting in his vehicle awaiting orders when it was hit by a shell, instantly killing him. Although the Mills were not to be used by civilian personnel, the caves were and at the end of October 1940, they were provided with Elsan Closets. Accounts tell of the treats given by the Mills army caterers to the children who almost resided in the caves through out the war. A particularly favourite was ‘dosh’ a rich, dark, treacly toffee.

Although more than three thousand children were evacuated from Dover to the safety of rural Wales following the military Evacuation of Dunkirk (26 May-4 June 1940), not long after they started to drift back. Yet from the start of the Battle of Britain on 10 July 1940 the town was subjected to bombing and shelling that was not to let up until September 1944. In consequence, for safety reasons, many children spent their nights sleeping in the caves even though they were cold. On the night of 30 October 1941 William Benn, nearly five-years old, died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a coal fire in a bucket put in an Oil Mill cave to keep him and his siblings warm.

From the end of 1944, when the Germans had been driven from France, the Oil Mills became one of three transit camps in the town, dealing with well over 4,000,000 troops. They ceased to be used for this purpose in August 1947. Two years later a clothing manufacturing firm opened in the Mills renamed Commercial Buildings. The complex, over the next few years, housed a number of diverse industries from a foreign mail sorting office to a maker of fur fabrics.

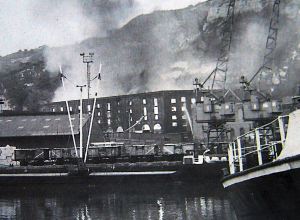

On the night of 23 May 1965, the watchman called the fire brigade. Within 17 minutes of the call, over half the buildings were enveloped in flames and the night watchman was trapped on the second floor. To gain access the fire brigade had to force open the gates, which was guarded by a ferocious Alsatian dog! While the brigade rescued the trapped man and tackled the fire, Harbour Board police controlled the dog. By 05.00hrs, the whole of the main building was alight and 50 firemen were pumping 100 gallons of water every minute on to the flames shooting some 60-feet into the air – the smoke could be seen in both Folkestone and Deal.

The closure of the adjacent railway line was ordered – it remained closed for several days – and it took 40 hours to bring the blaze under control. The cause of the fire was never ascertained but the damage was estimated at £1million and at least three factories were put out of action. Following the catastrophe, fire officers John Walton and Allen (Sam) Cook undertook a survey of all the known underground sites in Dover and the maps, diagrams they made.

Following the fire, George Hammond (Shipping) Ltd purchased the site, developing it for their head office and warehousing activities that opened in 1973. The origins of the company go back to 1767 when John Hammond started a shipping agency in Deal (1767-1922) and over the years had offices in Ramsgate (1838-1899) and in Margate (1848-1899) and coming to Dover in 1875 and amalgamating with Latham’s shipping company. Later, the company took the name George Hammond & Company retaining the name but becoming Limited in 1961.

The company was engaged in Ships Agency, looking after cargo vessels and calling mail liners together with salvage and rescue work. After World War II, the company started a Deep Sea Pilotage service in the English Channel and North Sea. In the 1960s, they expanded into stevedoring, specialising in fruit, timber and wood pulp cargoes, developed in warehousing, road transport, ro-ro clearances and from 1972 into petrol retailing and the building of the Dover Motel, Whitfield, jointly with Townsend/European Ferries. In 1992 the company was reconstituted as George Hammond PLC and in 2006 moved from Limekiln Street to the Aycliffe Business Centre.

The site of the old headquarters on Limekiln Street is now a petrol retail service station and the entrances to the Oil Mill caves can easily be seen from the pavement on Limekiln Street. Adjacent caves were subject to another fire in the early hours 17 March 1995, access for fire fighting equipment was almost impossible and the fire spread. It was almost 24 hours before the fire was brought under control. Parts of the tunnels are still used for storage and workshops. According to Derek Leach (Dover’s Caves and Tunnels Riverdale Publications 2011), altogether, there are 19 entrances leading to these caves and in places they are cavernous and 30-feet high.

- Presented: 08.01.2014