The Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust (ABCT) is a registered charity that was founded in 2006 as a non-profit organisation. They work to preserve and protect airfields in Great Britain, as well as educating people about their history and providing support to help enthusiastic young people to secure airfield or aviation-related employment. Another aspect of their work is gathering and making available information on different airfields history and this can be seen on their website: http://www.abct.org.uk. Finally, and particularly relevant to this essay, is that they place inscribed memorial stones on or near disused airfields.

In and around Dover there were five airfields set up prior to or during World War I, Capel, Guston, Marine Parade – Dover, Swingate and Whitfield. Each one is honoured with an ABCT memorial or plaque. These airfields played an important role in the history of British aviation as did some forty other airfields that were set up during that period. Glimpses of their stories, along with Dover’s airfields stories, are told below.

It is now generally recognised that Fambridge in Essex was Britain’s first ever purpose built airfield. Founded in February 1909 by aviator Noel Pemberton-Billing (1881-1948) Fambridge airfield was built on reclaimed marshland. This meant that drainage was a problem, in consequence the site closed in November 1909. In honour of the former airfield’s status, ABCT erected a memorial stone there in February 2009, one hundred years after the airfield opened!

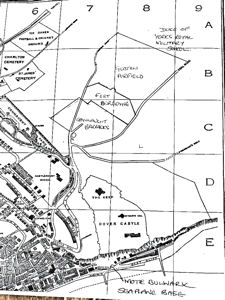

Five months after the Fambridge airfield opened, on the morning of Sunday 25 July 1909, Louis Blériot (1872-1936) crossed from Sangatte, France to England. He was flying his Blériot No XI 25-horsepower monoplane and the flight was the first heavier than air to make the Channel crossing. He landed on Northfall Meadow, between Swingate and Dover Castle, Dover and the journey had taken him 36minutes 30 seconds. Besides making history, Blériot instigated the meteoric rise of interest in aviation.

Orville and Wilbur Wright followed by Horace Short possibly at the Eastchurch factory. Eveline Larder

On 17 December 1903 near Kitty Hawk, South Carolina, United States, bicycle manufacturers Wilbur Wright (1867-1912) and his brother Orville (1871-1948) made the first ever controlled and sustained powered flights landing on ground at the same level as the take-off point. By 1905 the brothers had built a flying machine with controls that made it completely manoeuvrable and that was another first. However, the US Army showed no interest in this new machine. Hence, in 1906, when an American patent was granted to the Wright brothers they entered agreements with European firms.

Early contacts with the Wright brothers in America by aeronaught Charles Rolls (1877-1910) helped balloon manufacturers, Horace Short (1872-1917) and his brother Oswald (1883-1969) to gain the right to build the Wright brothers aeroplanes. They lived at Mussell (Muswell) Manor, at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, north Kent and the Wright Brother’s contract enabled them to consider opening an aeroplane manufacturing factory.

Memorial at Leysdown Airfield and Kenneth Bannerman Chairman of the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust

Pioneer aviator Francis Kennedy McClean (1876-1955) owned land at Leysdown near to Eastchurch, Kent. He joined forces with the Short brothers and in February 1909 they opened an aircraft production factory at Eastchurch with an airfield at nearby Shellbeach, Leysdown. The following year they laid another airfield at Eastchurch and the Leysdown Airfield became the base for the Aero Club of which McClean was a founder member. Not long after the army moved into the Leysdown site for military training purposes though they allowed the Aero Club to continue to use the airfield. In the spring of 1909 the Wright brothers came to England as guests of the Aero Club and Charles Rolls acted as their official host. During that time they visited the Eastchurch Short factory.

The idea of the Aero Club had been born in September 1901 when Charles Rolls and his friend and fellow balloon pilot or aeronaught as they were called, wine merchant Frank Hedges Butler (1855-1928) along with Butler’s daughter Vera, were taking a trip, probably in a balloon. Vera, so the story goes, suggested the formation of an Aero Club within the Automobile Club of which both Butler and Rolls were members. They discussed it, and on the insistence of Vera, agreed that the new club was to be open ‘equally to ladies and gentleman, subject to election’. In 1903 the Aero Club of Great Britain was launched for aeronaughts but with the increasing popularity of aeroplanes the Club broadened its remit to aviators. In 1910 the Aero Club was granted the Royal prefix becoming the Royal Aero Club (RAeC).

One of the experiments appertained to hydrogen, the gas used for ballooning as it it is lighter than air so has a good lifting capacity. It is also cheap to produce but is highly flammable. In the United States they were using helium that had similar lifting power as hydrogen but was considerably safer as it is an inert gas that cannot burn. However, helium is a natural resource that was found in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas and the Americans tightly controlled their monopoly making it very expensive to buy. The Army School of Ballooning found that both hydrogen and helium were preferable to hot air balloons as they required less effort and could stay aloft for much longer periods. Hence, as a result hydrogen filled balloons were preferred and adopted by the British Army. In 1890 the RE Balloon section became a permanent unit of the Royal Engineers establishment and the School moved to Stanhope Lines, Aldershot, Hampshire with a designated airfield. This was on Laffan’s Plain a large area of land used for Army training and named after Robert Michael Laffan (1821-1882) and called the Aldershot Airfield.

British Army Cody aeroplane Mark IB at Laffan’s Plain, Aldershot, being pulled into position by a team of soldiers. RE

From 1897 the School was called the Balloon Factory and a special RE Balloon section were trained to use balloons operationally. They took part in the Second Boar War (1899-1902) and experiments with cameras were undertaken for air photography and in the summer of 1906 RE balloonists took the earliest known aerial photographs of Stonehenge. In 1902 the Balloon Factory began experiments with ‘dirigible balloons’, better known as airships. Balloons are a lighter than air craft that can lift but are very much dependent on wind direction. By way of contrast, an airship is a lighter than air craft that not only lifts but is also powered by an engine(s). This enables it to move in any direction, even against the wind. By 1909 much time was being spent on the research of the different types of envelopes for airships and also the different types of gondolas in which crew, passengers and goods could be carried. Aeronauts such as Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe (1877-1958) generally called Alliott Roe or A.V. Roe, who later in 1910 founded the Avro Company in Manchester, worked at the Balloon Factory undertaking experiments with airships. While Samuel Franklin Cody (1867-1913) and John William Dunne (1875-1949), both aeronauts made significant contributions, particularly on engine design. Requiring more space to inflate the new ‘dirigible balloon’ or airship, which was then under construction, it was decided to move to a larger area. Between 1904-1906 the military Balloon Factory was relocated about 5 miles away on Farnborough Common.

At the time Germany was spending a great deal on balloon based aeronautical research. The British Government having recognised the military potential of balloons were also interested in aeroplanes. The Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), approved the formation of an ‘Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ and an ‘Aerial Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence’. Both committees were composed of politicians, army officers and Royal Navy officers, one of the latter was Captain Murray Fraser Sueter (1872-1960). Albeit, after aeronaught John Dunne reported that a German airship had been reported as being able to travel at 40 miles an hour, discussions took place on the production of a rigid airship. Based upon the German Zeppelin. £2,500 was spent on research and a prototype airship HMA No1 and called Mayfly was constructed under the supervision of Captain Sueter. However, on 24 September 1911, while attempting its first flight during strong winds, the airship broke in half and the project was abandoned. Nonetheless, the exercise provided valuable training for both designers and air crews.

The French government considered air travel to be feasible but preferred aeroplanes. This enabled Blériot and Anglo-French aviator, Henri Farman (1874-1958) to undertake research and development. Farman built a biplane more stable than the Wright aeroplane. The Americans, less than a year after rejecting the notion of a powered flying machine such as the Wright brother’s aeroplane changed their mind. They decided to back the development of a powered flying machine designed by American Samuel Cody. At the time Cody was actually in England working as a civilian Kite Instructor with the Army Balloon Factory at Farnborough. On 16 October 1908 on Farnborough Common, Cody made his first flight – the first official flight of a piloted heavier-than-air machine in Great Britain! Albeit, as work was being carried out on developing the Mayfly airship, Army funding on aeroplanes ceased but Cody was able to keep the aeroplane. On 14 May 1909, at Laffans Plain, Aldershot some 5miles from Farnborough Common, he succeeded in flying about 1,400 feet before crashing. Nonetheless, he established the first official British distance and endurance record.

That summer the Short Brothers produced and sold six Wright Flyers and they received headline coverage when aviation pioneer John Theodore Cuthbert Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara (1884-1964) became the first resident Englishman to make an officially recognized aeroplane flight on 2 May 1909. On 30 October that year Moore-Brabazon flew a Short No 2, a circular mile in a Daily Mail newspaper competition and won £1,000 prize money. Also in October 1909 Britain staged its first air show, which was held at Doncaster Racecourse. Around twelve aviators took part including the French aviators Léon Delagrange (1872-1910) and Roger Sommer (1877-1965) as well as Samuel Cody.

Also that year, more airfields were opening but often little thought was given to their terrain, length or even general suitability. Albeit, the pioneers of the British aircraft manufacturing industry, such as Frederick Handley Page (1885-1962), took a more professional stance and opened a purpose built factory in June 1909. This was on the north bank of the River Thames, just east of Creekmouth where he laid down an airfield close by. A contemporary account of the Creekmouth Airfield, published in Flight Magazine August 1909, stated that it was about 2½ miles long and about a mile wide and was situated between Barking and Dagenham Stations on the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway. A flat part of the airfield was being levelled for starting purposes and an artificial hill was erected for gliding experiments. As well as Creekmouth Airfield from about July 1911 the company also used Fairlop Aerodrome at Ilford , which was already being used by aircraft designers and builders, Helmuth Paul Martin (1883-1968) and George Harris Handasyde (1877-1958). In 1908 they had built the monoplane Martin-Handasyde No 1 there where its first and only trial, was piloted by Martin on a very windy day. The heavy weather brought the prototype down wrecking it but despite this setback, Martin and Handasyde went on to design and build a succession of monoplanes. These included the one flown by test pilot Edward Petre (1886-1912), which on Christmas Eve 1912 was also brought down by heavy weather.

Martin and Handasyde continued to build aeroplanes but it was their S.1, built in 1914, that turned the company into the United Kingdom World War I (1914-1918) third most successful aircraft manufacturers. Meanwhile, in September 1912, Handley Page closed both the factory and Creekmouth Airfield and re-established both at Cricklewood. During the War the company became famous for their heavy bombers built at Cricklewood for the Royal Navy with the intention of bombing the German Zepplin Yards. They were flown from the company’s adjacent Cricklewood Aerodrome. In 1920 Handley Page inaugurated a London to Paris air service from Cricklewood Aerodrome but in 1929 the aerodrome was closed to make way for suburban development. Following the success of the Martin-Handasyde S.1, Martin and Handasyde opened a factory at Woking, Surrey but used Brookfield airfield in preference to Fairlop Aerodrome for testing. At the same time and also after the War the company became particularly well known for their motorcycles. Meanwhile Fairlop Aerodrome remained in use during both World Wars.

Why, after the outbreak of War in October 1914 Fairlop Aerodrome was rejected by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in favour of the creation of a new airfield at nearby Hainault Farm, is unclear. However, a RNAS report did state that the site was chosen as a Day Landing Ground because it featured well-drained land that was surrounded by open countryside in all directions and was close to railway stations, useful for personnel travelling there. In February 1915, Hainault Aerodrome was transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, which had already taken over Fairlop Aerodrome, when they were looking for suitable sites east of London. This was to protect the City from German bombing raids as part of a ring of ten aerodromes around London. Hainault Aerodrome closed in 1919 but shortly before World War II the City of London Corporation bought the site intending it to be London Airport. However, at the outbreak of War it was requisitioned together with Fairlop Aerodrome as an air and military base. Both Fairlop and Hainault closed in 1946.

In November 1909 the Short brothers opened their newly built Eastchurch airfield on the marshes. Whether the Admiralty had been preparing for what became World War I is debatable, but in 1898, work started on converting Dover Harbour into the Admiralty Harbour, that was to last for over 100years. The new harbour was built as the base for the Royal Navy at the southern end of the North Sea and on Friday 15 October 1909, it was opened by the Admiral of the Fleet, George, Prince of Wales, (later George V 1910-1935).

1910

Swingate Aerodrome named by Charles Rolls when he made his memorable flight. Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust. Mike Weston 2023

In the spring of 1910, Charles Rolls saw Swingate Down plateau on the east side of Dover and overlooking Admiralty Harbour, as having potential for an airfield. He persuaded the War Office to rent the Down to him when it was not required for military purposes. Rolls renamed the plateau Swingate Aerodrome and had an ‘aeroplane garage’, or hangar as they were soon after called, erected by William Harbour Ltd of St Mary Cray, Kent. That company was later commissioned to build hangars on many of the newly created airfields that were to open after Rolls’ successful flight. That took place at 18.30hrs on Thursday 2 June when Rolls took off in his Wright Flyer from the Aerodrome, passed over Sangatte, France at 19.15hrs. After re-crossing the Channel back to England, Rolls circled around Dover Castle and finally landed at Swingate Aerodrome at 20.00hrs having made the first two way Channel crossing in an aeroplane.

That same year, aviation pioneer Edwin Rowland Moon (1886-1920) flew his Moonbeam 2 monoplane from the meadows of North Stoneham Farm, Eastleigh, Hampshire. He had made his first successful flight in an aeroplane he built himself in the corner of the family boat builder’s workshop. At the outbreak of World War I Moon joined the Royal Naval Air Service and became a pilot and eventually a test pilot at RAF Felixstowe. Following the War he stayed on at Felixstowe but on 29 April 1920 he was instructing a crew in a Felixstowe F5 N4044 flying boat when suddenly there was a loud crack, the aeroplane went into a spin, crashed and Moon was killed. In the meantime just before the outbreak of War there was a public flying display given by Gustav Hamel to an audience of ten thousand! A few weeks later Eastleigh Airfield was requisitioned by the Royal Flying Corps and renamed ‘Eastleigh Airfield Aircraft Acceptance Park’ then in 1917 the renamed Atlantic Park, site was given over to the United States Navy to develop an assembly area.

In 1932, Atlantic Park was purchased by Southampton Corporation and renamed Southampton Municipal Airport with regular air services to the Channel Islands. During World War II the Airport was again requisition but marking the return of the wartime aerodrome to a municipal airport in 1945, the regular air services to the Channel Islands resumed. In the 1960s J N Somer bought the Airport and during his tenure made a number of improvements including the construction of a 5,653 feet concrete runway. In 1988 a consortium headed by Peter de Savary (1944-2022) bought the airport site for redevelopment then in 1990 it was sold to the British Airport Authority, that had been privatised in 1987. Major reconstructions took place and in 1990 what had started off as the tiny Eastleigh Airfield was renamed Southampton International Airport by Prince Andrew, Duke of York. Edwin Rowland Moon was credited as being the first person to fly from there!

From about 1862 what eventually became Hendon Aerodrome, Middlesex, seven miles north west of Charing Cross at Colindale close to Brent Reservoir, was a balloon airfield. The first powered flight to take off from there was an 88-foot long non-rigid airship built by C G Spencer & Sons’ airship factory at 56a Highbury Grove, Islington. On Tuesday 6 February 1909 the airship, piloted by Henry Spencer (1877-1937) took off carrying just one passenger, the Australian suffragette Muriel Lilah Matters (1877-1969). In fact Matters had hired the airship and emblazoned on one side of the balloon was the slogan ‘Votes For Women’ and on the other ‘Women’s Freedom League.’ The airship rose to a height of 3,500 feet and Matters scattered 56 pounds of handbills promoting the Women’s Freedom League. The flight made headlines around the world when it was stated that Matter’s had made the first ever powered flight from the airfield.

Albeit, in 1906, the Daily Mail newspaper had challenged aviators to fly from London to Manchester or vice versa, the prize being £10,000. The journey had to be completed within twenty-four hours, with no more than two landings allowed. For the race railway companies painted the rail sleepers white along the route to be followed. On 27 April 1910 French aviator Louis Paulhan (1883-1963) set off from Hendon Airfield and flew 117 miles to Lichfield. Before dawn on 28 April he took off and after 3 hours 55 minutes in the air reached Burnage on the outskirts of Manchester. Paulhan had not only won the prize, he is recognised as the first person to make an aeroplane flight from Hendon Airfield! About this time aviator, Claude Grahame-White (1879-1959) purchased more than 200 acres of land converting Hendon airfield into a recognised aerodrome. He employed the London Aerodrome Co to build sheds and in 1910 opened the Bleriot Aviation School. The following year, as part of the George V (1910-1936) coronation celebrations (9-16 September 1911), the first ever ‘official’ UK airmail was flown from Hendon to Windsor and vice versa.

During World War I, Grahame-White’s company concentrated on aircraft production and to facilitate the transportation of the 3,500 workers and materials, Midland Railway built a spur from the embanked main line with a platform close to the main line and a loop around the airfield to the plant. In November 1916 the War Office commandeered the Bleriot Aviation School and subsequently 490 pilots were trained there. Hendon Aerodrome was the first aerial defence airfield of a city as part of a ring of ten aerodromes around London. After World War I, the airfield became famous for pioneering experiments, including the first parachute descent from a powered aircraft and the first night flights. However, in 1922 the Air Ministry took over the aerodrome and factory. This led to an ugly three-year legal fight after which Grahame-White left and had nothing more to do with aircraft production. RAF Hendon was briefly involved in the Battle of Britain (1940) during World War II but thereafter the aerodrome was mainly used for transport activities notably flying dignitaries to and from London. Following the War the demand for housing put pressure on the RAF to relinquish the aerodrome and the Metropolitan Communication Squadron was the last flying unit to leave left Hendon and that was in November 1957. The RAF remained operating as a Supply Control Centre and the Joint Services Air Trooping Centre. However on 1 April 1987 the RAF base closed and it is now the site of the Grahame Park Housing Estate and Hendon Police College. The Royal Air Force Museum, London, is situated on south east side of the former aerodrome site. In 1968 a Blackburn Beverley, an exhibit at the new RAF Museum, landed at what was left of the airfield – the last aircraft to use the field.

Freshfield Beach, Merseyside, from where Paterson made his historic flight 10.05.1910. Mike Pennington

Throughout the country the interest in flying was gathering momentum and none more so than on the Lancashire side of the Mersey River. Freshfield, is part of the town of Formby on the coast of the Mersey and it is said that it was on this Merseyside beach that Sam Cody established an ‘aerodrome’ in the autumn of 1909. Cody planned to use the beach to make an attempt at the first flight between Liverpool and Manchester. In the event he opted for Aintree but was not successful. Nonetheless, the Aintree Airfield was laid out on the famous Grand National racecourse site and Sam Cody made several demonstration flights there in November that year. Aintree airfield remained and during World War I the airfield was used by the Cunard Steamship Company who managed National Aircraft Factory No 3 where they made Bristol F.2b fighter aircraft. Albeit, on Saturday 10 May 1910 at 15.30hours the Freshfield Airfield achieved fame as the country’s first ‘Beach Aerodrome’, that is an airfield on the beach next to the sea! That Saturday, Cecil Compton Paterson (1885-1937), who up to two years before had ran a prosperous motor business in Liverpool, took off from and landed his biplane on Freshfield’s wide flat sands. In the intervening time Paterson had sold his business to Liverpool Motor Company becoming a director and using the facilities to build a biplane to the design of the Curtiss Golden Flyer.

Paterson, having gained RaeC certificate in December 1910, following his successful flight approached Southport Town Council for a grant of £500 to open an aerodrome and flying school on Fairfield’s sands. Southport Town Council expressed interested but thought Paterson’s project cost too much. Instead they opted to construct a municipal airfield with a hangar adjacent to the beach at Hesketh Park paying John Gaunt £150 to become Southport council’s aviator! In the summer of 1910 Gaunt flew his biplane from Hesketh Park Aerodrome up and down Southport beach for the benefit of large crowds. Thereafter the council’s aerodrome was little used until WWI when it was commandeered for military service as No.11 Acceptance Park. During the inter-war period Norman and Percy Giroux operated the Giro Aviation Company from Hesketh Park. They offered a regular aeroplane service to Blackpool, Isle of Man and Ireland as well as pleasure flights and pilot training. World War II saw the airfield become No.7 Aircraft Assembly Unit, when Mosquito and Anson aircraft were assembled as well as the repair of Spitfires. Following the War Hesketh airfield was used by Southport Aeroclub until 1961 but flying continued until the airfield closed in 1965.

Meanwhile in 1910, at Freshfield, Paterson, having already built a hangar for his biplane, built a second and subsequently three more hangars in the dunes. He also built a second biplane with a larger engine for aviator Gerald Higginbotham (b1877) of Macclesfield who kept it in one of the newly constructed hangars. Other aviators were using Freshfield airfield, including Robert Arthur King (b1883) from Neston who later became a Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Reserve and was stationed at the Central Flying School at Upavon (see below). Paterson and King, on 29 November 1910, made the first crossing of the River Mersey by air flying a Farman biplane. Another aviator was Henry Greg Melly from Aigburth (1868-1957) who after building a Blériot monoplane in Shed 3, moved to Waterloo Sands, Crosby on the Mersey. There he built two wooden sheds and a workshop for his two Blériot monoplanes – one of which he had built at Freshfield aerodrome.

Melly subsequently built another Blériot monoplane and in 1911 opened the Liverpool Flying School and became the first full time flying instructor in Lancashire. With one of his pupils, Alfred Dukinfield-Jones (1888-1976) Melly flew from Aintree to Trafford Park, Manchester, on 07 July 1911 in a Blériot XI. At Trafford Park, Alliott Roe had created a well marked landing area for his newly opened 69AVRO company nearby. The flight appears to be the first between Liverpool and Manchester. During World War I Waterloo Sands was designated a Diversion/Emergency Landing Ground for aircraft in transit up the west coast to Scotland and following the War the Avro Transport Company used the airfield for Avro 504s as well as their own. Southport council, in 1911, opened another airfield at Blowick, Southport, to attract summer visitors by holding air displays including well known aviation pioneers such as Claude Grahame-White.

That year Paterson moved to Hendon to work for Claude Grahame-White as a flying instructor and while there built a two seater biplane with a more powerful 50-h.p. Gnome engine for Higginbotham. This flew for the first time on 18 October 1911 and two days later Higginbotham flew to Southport from Freshfield Aerodrome to make the first aerial delivery of mail in the North West of England. At about the same time Freshfield became the testing ground for aviator Robert Cooke Fenwick (1884-1912) who tested the Planes Ltd biplane and Merseyside Military monoplane fitted with a 45-h.p. Isaacson engine as Handley Page’s first employed test pilot. In December 1911 Fenwick flew the Merseyside Military monoplane to a War Office trial for military aircraft at Larkhill, Wiltshire and again in August 1912. On both occasions he flew from Freshfield but on 13 August, just after 18.00hrs, Fenwick’s plane was seen in difficulties. The aircraft plunged for about 50 feet, recovered to an even keel then made a vertical dive to the ground. Fenwick was killed instantaneously. Although these Mersyside airfields have long since gone, in 1941 RAF Woodvale opened as an all-weather night fighter airfield for the defence of Liverpool and today operates as a training station and is the home of Liverpool University Air Squadron.

The growing interest in learning to fly inspired a officers in both the Army and the Royal Navy, to learn. Staff from the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company trained many of these officers to become qualified pilots. The Company was a subsidiary of the Bristol Tramways Company and was founded by George White (1854-1916) together with his brother Samuel (c1862-1928). The Company’s factory was at Filton near Bristol where the two brothers built a factory, which opened in March 1910, to build aircraft to improve existing aeroplane designs. Close to the factory was a small ‘flying ground’ at the top of Filton Hill. As the Company flourished, it was referred to as the Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC). During World War I, like Eastleigh, the airfield was taken over by the Royal Flying Corps and named Filton Airfield Aircraft Acceptance Park. This involved the final assembly and flight testing of aircraft sent from other aircraft production sites.

The last flight of any Concorde, 26.11.2003. G-BOAF overflying Filton Airfield at 2,000ft. Adrian Pingstone

During the interwar period the military airfield facilities were expanded to that of a full flying base built by the Army. The runway was lengthened and Filton became part of an operational fighter base. Following World War II, in 1947, RAF Filton closed as a military airfield and factory but both physically remained and they reverted to their original owners BAC. In 1960, the British Aircraft Corporation took over the aircraft interests of BAC and the development and production of Concorde took place at Filton. To accommodate Concorde the main Filton runway, which had already been extended several times as Filton Aerodrome expanded, was further extended. However, on 26 November 2003, Concorde 216 (G-BOAF) made her last flight, this was from Heathrow aerodrome and she was flown westward over Bristol, where crowds waved as she passed over, and then to Filton Aerodrome, where she landed. Not long after, much of the Filton Aerodrome was sold off for the Patchway housing development and Trading Estate. British Aircraft Corporation remained on what was left eventually becoming a forerunner of British Aerospace. Then, on 31 December 2012, the site finally closed. However, Airbus UK purchased 26 acres of the former Rolls-Royce Rodney Works that had operated close to the original Filton Airfield. There they built a facility for wing development and manufacture and now they are the main company on this former airfield.

About 1898, the War Office bought farmland on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, for military training purposes. By the following year a large tented camp for Army units training was established called Larkhill Range. In 1909, Horatio Barber (1875–1964), rented a small piece of land on Larkhill, adjacent to the military camp and built a hangar to house his new aeroplane. More enthusiasts soon joined him including George Bertram Cockburn (1872-1931) and Captain John Duncan Berties Fulton (1876-1915). At the time Fulton was stationed at Bulford military camp on Salisbury Plain and had bought a Grahame-White Blériot-type monoplane out of the proceeds of patents for the improvement of field guns he had invented. During 1910 Cockburn and Fulton became such good friends that in November Fulton gained his RAeC Aviators Certificate flying Cockburn’s Farman I-bis. They also manage to persuade the War Office of the need for a military airfield for aeroplanes. The Army extended their Durrington Down military site to include an airfield and in July 1910 Larkhill Aerodrome, the first military airfield in Britain designated for aircraft as opposed to balloons, opened.

Several more hangars were built at Larkhill next to the hangar that Barber had built. Barber’s hangar still exists along with a three-bay hangar and the Army gave the contract for building hangars to BAC. On 1 April 1911, No. 2 Company of the Air Battalion – Royal Engineers was established at Larkhill, the first flying unit of the armed forces to use aeroplanes as opposed to balloons and Fulton was appointed to command. This evolved into No. 3 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps in May 1912, the first Royal Flying Corps squadron to use aeroplanes. On Friday 30 September, aviator Robert Loraine (1876-1935), who first named the aircraft control stick a ‘joystick’, was asked to test an upgraded Farman biplane.

Guglielmo Marconi publicity photograph in front of his early radio apparatus. Smithsonian Institute Library

The aeroplane had been adapted with a basic Marconi wireless transmitter weighing 14lbs. Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) had been demonstrating revolutionary new techniques of communication by radio wave-based wireless telegraph system in England since January 1897. The machine was attached to the passenger seat and monopole antenna wires stretched along the breadth and length of the biplane. The Morse key for tapping out messages was fixed next to Loraine’s left hand and he was asked to send a predetermined message while flying over Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain, approximately 2 miles away. This he did with his left hand while controlling the aeroplane with his right. In a hangar at Larkhill, surrounding the Marconi receiver were Marconi engineers, a number of dignitaries headed by the Home Secretary (1910-1911), Winston Churchill (1874-1965) as well as army and navy officers. Loraine did as he was bid and the dignitaries were delighted when the message ‘enemy in sight’ was received on the apparatus in the hangar. However, the dignitaries generally expressed reservations about the use of aeroplanes for defence purposes.

Brooklands motor racing circuit opened in 1907 near Weybridge, Surrey, and just south-west of London in south-eastern England. The track was 2.767-mile long, 100 feet wide, with banking nearly 30 feet high. It was the world’s first purpose-built ‘banked’ motor racing circuit. Hugh Fortescue Locke King (1848-1926) who had inherited the estate, founded and financed the venture, for at the time, Britain lagged behind European countries in the development of motorcars. Locke King decided to try and redress the balance by building a testing track to give impetus to the industry. The track was opened on 17 June 1907 and on that day 43 cars were driven around the circuit, one of them by Charles Rolls. The motor racing circuit quickly proved popular with many of the competitors also interested aeronautics, notably Alliott Roe who in 1910, founded the Avro Company in Manchester. In 1908 Alliott Roe made the first flight of an English aircraft by an English pilot at Brooklands. At one of the motor racing meetings Roe met aviators Louis Paulhan, who won the London-Manchester air race that year and Henry Farnham. The three men persuaded Locke King to lay an airfield alongside the motor racing track. Before Brooklands Aviation Ground, opened in early 1910, Roe built workshops close to the airfield to attract his London social friends and financial backers to the site.

Brooklands quickly became a British major flying centre with a number of aviators making their base including brothers, solicitor Henry Aloysius Petre (1884-1962) and Edward Petre, who built a single-seater monoplane with a wooden fuselage. This was shown at the Olympia Aero Show London in March 1910 and was taken from there to Brooklands. In Shed No.11 at the airfield the aeroplane was completed making its one and only flight on 23 July 1910, piloted by Henry Petre . Following this experimental flight Edward, tested aeroplanes for Handley Page and also for aircraft designers Martin and Handasyde at Fairlop, Essex. Flying a Martin Handasyde monoplane, Martin Petre took off from Brooklands at 09.10hours on 24 December 1912. The intention was to fly to be the first person to fly to Edinburgh non-stop and the weather was favourable as a fresh breeze was blowing and the sky was clear. The planned route was to leave Brooklands and fly overland in a north-easterly direction until he reached the Wash. Once there he would go north following the coast until he reached Newcastle then turn in a north-westerly direction cross country to Edinburgh. However, by the time he reached the Wash wind speed was increasing and continued to gather strength the further north he flew.

By midday a gale was blowing but Petre could see the long sandy bank of the River Tyne which he followed towards Marske-by-the-Sea, north Yorkshire. There he turned his craft inland probably with the intention of landing on Marske airfield behind the beach. He knew that Marske beach had been used back in 1908 by Robert Blackburn (1885-1985) and his wife Jessy (1894-1975) to test their aeroplanes what they had built in Leeds. News of this had spread throughout the aviation world and Marske beach had earned the reputation of being a good landing ground. Indeed, on 25 June 1910 an air show was held on farmland, west of Marske village across the the coast road from the beach. For the event the farmland was flattened and the site was billed as Marske-by-the-Sea Aerodrome. On that December day in 1912, according to locals, it was the aerodrome that Petre was making for. He was almost making touch down when a sudden fierce gust of wind seem to catch the plane and it rose about 40feet into the air. The wings seemed to collapse and Petre appeared to lose control of aeroplane. It crashed in the village, about 400 yards from the St Mark’s Parish Church, killing Petre.

At the inquest into Petre’s death George Handasyde, the Martin and Handasyde chief engineer, gave evidence. He stated that the machine used by Petre had a normal power of 80mph and described Petre as ‘a big, powerful man, and one of the most fearless aviators in the country.’ Officers from the newly created (April 1912 see below) Royal Flying Corps inspected the site but noted that Marske-by-the-Sea airfield failed to come up to the standard airfield design. A verdict of ‘Accidental death’ was returned and Edward Petre was buried at Fryerning Churchyard, Ingatestone, Essex. Of note Henry Petre, Edward’s elder brother, later became a founding member of the Australian Flying Corps. Of note, in the Parish Church of St Martin’s Marske-by-the-Sea, on Sunday 1st November 2015 the Bishop of Whitby, the Rt. Revd Paul Ferguson, dedicated a stained glass window to Edward Petre. The window was created by Ann Sotheran, Churchwarden of St Mark’s Church and is based on a schematic map of eastern Britain. It shows Petre’s route from Brooklands Airfield to Edinburgh marked with a red line and the site of the crash near the Parish Church.

Brooklands continued to attract aviators and would be aviators. Entrepreneur and aviator Hilda Hewlett (1864-1943) seeing this joined forces with Gustav Jules Eugene Blondeau (1871-1975) opened Britain’s first flying school nearby. BAC followed, establishing a flying school in late spring 1910. The company’s first instructor and test pilot was Archibald ‘Archie’ Reith Low (1878-1969). Alliott Roe also opened a flying school at Brooklands and in July that year BAC opened a second flying school near Larkhill Aerodrome. In 1912 Vickers engineering company opened a flying school having expanded into aircraft manufacture the year before.

One of the Vickers instructors was Richard Harold Barnwell (1879-1917) who became a test pilot for the company. The Vickers flying school taught 77 pupils to fly before it closed in August 1914, one of which was Hugh Dowding (1882-1970), the Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain 1940. From then on, aviation companies and associated industries also set up close to Brooklands, including Sopwith Aviation Company owned by Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith (1888-1989). During World War I Brooklands motor racing circuit closed, as did the civilian flying schools and Vickers Aviation Ltd opened a factory there in 1915. Other associated factories followed and by 1918 Brooklands had become Britain’s largest aircraft manufacturing centre. During the War various Royal Flying Corps Squadrons were based at Brooklands and air-ground wireless trials pioneered by a Marconi team, that had started in 1912, continued with the World’s first voice to ground wireless message successfully transmitted over Brooklands in 1915.

In late 1917, three large ‘Belfast-truss‘ General Service Sheds for a new Aircraft Acceptance Park were erected to enable assembly and testing new aeroplanes until it closed in early 1920. In 1927 Vickers Limited, the largest aviation manufacturing company at Brooklands, merged with Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company to form Vickers Armstrong. As the British economy picked up in 1931 Brooklands Aviation Ltd was formed and the aerodrome became a major flying training centre. Motor racing at Brooklands ceased at the outbreak of World War II and the site was given over to war-time production of military aircraft in particular the Vickers Wellington, Vickers Warwick and Hawker Hurricane. To help screen the Hawker and Vickers aircraft factories at Brooklands trees were also planted into the concrete of the former racing circuit.

Brooklands – the end of an era as Ron Hedges removes the name plaque after 80 years of aircraft manufacturing Christmas Day 1989. BAE Systems

On 4 September 1940 the Vickers Brooklands factory was bombed, nearly 90 aircraft workers were killed and at least 419 injured. Following the war the former racing circuit was sold to Vickers Armstrong when the design and production of new aircraft increased such that in the 1960s aircraft production at Brooklands achieved its peak. In 1960 Brooklands became the headquarters of the newly formed British Aircraft Corporation. Two years later, to house the new prototype VC10, a large new 60,378 square-foot hangar, nicknamed ‘the Abbey’, was erected and in 1964 the larger ‘the Cathedral’, 98,989-square-foot hangar was erected. Brooklands was also the country’s major assembly factory for Concorde but lack of orders for VC10s and Concordes plus changes in Government policies led to a decline in aircraft orders. In 1977 Brooklands became part of the newly formed British Aerospace (BAe) and at about that time airfield activity ceased. All aircraft manufacturing at Brooklands was wound up and Brooklands aircraft manufacturing closed on Christmas Day 1989. Shortly after Brooklands Museum opened and BAe’s successor, BAE Systems has a logistics centre at Brooklands.

The Aero Club had, from 1905, issued Aeronauts’ Certificates for balloonists. On 15 February 1910 when the Aero Club was elevated to RAeC, it became the regulative body for issuing of Aviators’ Certificates to qualified aircraft pilots. The certificates were recognised by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale founded in 1905 and the world governing body for air sports. The first aeroplane pilot to qualify for a RAeC certificate was Moore-Brabazon. He had previously been assigned certificate number 40 of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and was issued with RAeC Certificate Number 1 on 8 March 1910. On the same day certificate No.2 was issued to Charles Rolls, who had flown a Short-Wright Biplane for his test flight.

On 21 June 1910, Lieutenant George Cyril Colmore (1885–1937) after completing training, which he had paid for out of his own pocket, became the first qualified pilot in the Royal Navy, certificate number 15. Hilda Hewlett was the first woman to receive a certificate, the number being 122. The RAeC, besides testing pilots on their ability to fly, they also trained most military pilots up until 1915. From then on most training took place at military airfields such as Swingate, Dover, but the trainee pilots still had to pass the RAeC test. Salisbury Plain was one of the main training grounds and scattered memorials across the Plain pay tribute to these first military flyers. Albeit, by the end of the First World War, more than 6,300 military pilots had received the RAeC Aviator’s certificates. Since its formation in 1972, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has regulated pilot licensing in the UK.

For 11-12 July 1910 at Hengistbury Head Airfield, Southbourne near Bournemouth in Dorset, a Pageant was organised to celebrate the Centenary of Bournemouth. It was hoped that the airfield would prove popular to wealthy locals and also bring wealthy visitors to the town. Hence, one of the attractions was an aviation meeting with competitions one of which was for the aviator to land his aeroplane as close as possible to a touch down point. One of the aviators attending was Charles Rolls who was flying a Wright Flyer with a modified controlling wire that had been attached to the tail. Having competed in the event on the first day but not satisfied with his result Rolls had another go on the second day a Tuesday. However, when he was about 80 feet above the ground the controlling wire broke and Rolls was thrown out of the aeroplane. He died from his injures shortly afterwards. Charles Rolls was the first person in Britain to die in an aircraft accident and a memorial to him was erected and is maintained by the Royal Aeronautical Society in what is now the rear playing field at St Peters School Hengistbury Head. Following the accident aviators lost interest in using Hengistbury Head Airfield and it was finally abandoned in the 1920s.

The summer of 1910 saw a number of aviation meetings planned but following the death of Charles Rolls, they were then cancelled. However with trepidation, the owners of Lanark Racecourse Airfield decided to carry on with their aviation meetings set for Saturdays 6 and 13 August 1910. The racecourse was reputed to be the oldest in Britain having been founded by King William the Lion of Scotland (1165-1214) who gave the Lanark Silver Bell as a prize. The bell disappeared for centuries but was found in 1836 in Lanark Town Council’s vaults and is competed for annually. In 1908, a new flat right-handed oval racecourse 10 furlongs round with a run-in of around 3+1⁄2 furlongs was laid. All the facilities both race horse owners and the paying public needed were provided but it did not attract them. The main reason was the lack of a railway line to bring people in from the populous Edinburgh and Glasgow. It was for this reason the owners decided to hold first aviation meeting in Scotland regardless of the death of Rolls near Bournemouth the month before.

With the right social connections the owners persuaded Caledonian Railway Company to constructed a railway line from the main Glasgow-Edinburgh line to Lanark. The Railway Company built the station near to the entrance of the racecourse in order, so they said, to enable the aeroplanes to be transported to the meeting by rail! The owners of the horse racecourse offered £8060 as prize money and the aeroplane races were to be accurately timed over straight measured distances which allowed records to be set for the first time. Further, the horse racecourse stables would be used as hangars for the aeroplanes. To protect spectators, no aircraft was to fly closer than 300 yards from them. The first Saturday arrived and so did aviators from seven countries with their aeroplanes! They all arrived by train as did about 80,000 people mostly from Edinburgh and Glasgow. The meeting held the following Saturday and attracted some 200,000 people! The racecourse continued to be used as an airfield until the 1950s including in both World Wars. In 1911 Scottish aviation pioneer, William Hugh Ewen (1873-1947) opened a flying school nearby. The racecourse closed in October 1977 but it is still an official emergency airfield. The railway station was officially opened on 27 September 1910 but in 1965 was subjected to the Beeching cuts. The Lanark Silver Bell horse race is now run at Hamilton Park Race Course, south of Glasgow.

Following the failed construction of the British prototype airship Mayfly in 1908-09 Captain Sueter, who had supervised its construction, continued to undertake pioneering work in naval aviation. In 1910 Oliver Swann / Schwann (1878-1948) was selected to assist Captain Sueter and using his own money purchased an Avro Type D landplane. Although not having qualified as a pilot Swann added floats to the aeroplane and successfully managed to fly it off water. Although Swann crashed the aircraft, this was the first aircraft take off by a British pilot from salt water.

1911

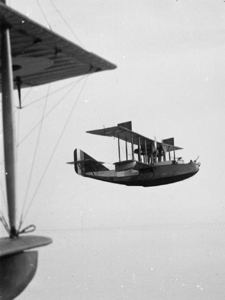

On January 26, 1911 Glenn Hammond Curtiss (1878-1930) an American aviation pioneer and one of the founders of the U.S. aircraft industry flew the first seaplane from water. At the time, in Britain, an aeroplane capable of rising from and alighting upon water was described in Flight magazine as ‘scarcely even dreamt of’. However, Edward Wakefield, an engineer who had been experimenting with the idea of producing a floatplane that could. decided otherwise. Wakefield ordered a floatplane similar to the design of the 1910 Fabre Hydravion – an experimental floatplane designed by Henri Fabre (1882-1984), an aircraft that had taken off from water under its own power. He commissioned Alliott Roe’s Manchester Avro Company to build seaplane based on their Avro Curtiss aircraft with modifications based on the Fabre Hydravion. Wakefield set up the Lakes Flying Company and what was to become the seaplane named Waterbird, was built at Brownsfield Mills, Manchester with wheels for testing at Brooklands. It was delivered to Lake Windermere on 7 July 1911 where conversion took place to the seaplane including the floats that were to replace the wheels. These were built by Borwick & Sons, boat builders of Bowness. Aviator, Herbert Stanley Adams successfully took off in the Waterbird floatplane on 25 November 1911 from Windermere and landing on the lake. This was the first successful British built seaplane to take off and land on water.

Together Wakefield and Adams went on to develop seaplanes but local residents complained. Most notably Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851-1920) internationally known as one of the three founders of the National Trust and Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), author and conservationist. However, the Home Office found no reason to control their activity. On 11 December 1911, Wakefield filed a Patent for float attachment to an aeroplane including rubber bungees for shock absorption when taking off and landing. The following year another Patent for a stepped float and in 1913 for wingtip floats, all of which were granted. Even though on water, Windermere Airfield was split between two locations, Cockshott Point and Hill of Oaks, further down the lake’s east side and became an RNAS base in WWI, closing in 1920.

In June 1911 an airfield opened on farmland at Whitfield, a village just outside of Dover. It was generally known as Dover Aerodrome! It was favoured by aeronauts who would fly to the airfield where they would leave their aeroplane, until they returned, before boarding a ferry to cross the Channel to France. Harriet Quimby, (1875-1912), an American journalist, gained her pilot’s licence in August 1911, the first woman to do so in the US. By Christmas, she had decided to be the first woman to fly across the English Channel and through contacts, managed to get a letter of introduction to Louis Blériot in Paris. On 1 March 1912, Harriet set sail from New York for London on the Hamburg-American liner Amerika, and on arrival put her plan to the editor of the Daily Mirror. She described Dover aerodrome, as the airfield at Whitfield just outside Dover as being, ‘a fine, smooth ground from which to make a good start. The famous Dover Castle stands on the cliffs, overlooking the Channel. It points the way clearly to Calais.’ Harriet then went to see Blériot and persuaded him to loan her a Blériot monoplane with a 50hp Gnome engine. She also persuaded the English aviator, Gustav Wilhelm Hamel (1889-1914), to help with her project.

Plaque commemorating Whitfield Airfield near Dover. It can be seen in the garden of Whitfield Holiday Inn. Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust. 2023 AS

On the early morning of Tuesday 16 April 1912 Harriet arrived at Whitfield airfield dressed in a flying suit of her trademark, purple wool-back satin, under which she wore two pairs of silk combinations. Over the apparel, to keep her warm, Harriet wore a long woollen coat in the style of an ‘American raincoat’ all topped with sealskin stole. At the airfield, Hamel undertook a trial run and satisfied with the monoplane, Harriet climbed aboard and took off at 5.30am. 59 minutes later she landed on Equihen beach in the Pas de Calais, the first woman to fly across the Channel! The following year Whitfield airfield ceased to be used as such but before Whitfield airfield was ploughed over it featured in one of the earliest recorded films of any British airfield by British Pathéone. Entitled, the Circuit of Europe International Air Race at Hendon, Shoreham and Whitfield. This can be seen on ABCT’s Whitfield page: https://www.abct.org.uk/airfields/airfield-finder/whitfield/

A month after Harriet Quimby’s memorable flight, Germany sent the gunboat Panther to Agadir, Morocco, supposedly to protect German firms even though the port was closed to non-Moroccan businesses. The Admiralty reacted by, among other things, ordering the Camber in Dover Harbour to be altered into a submarine basin. The depth was deepened to 17-feet (5.19 metres); a pair of breakwaters and submarine shelters were constructed with a small dry dock alongside. As international tensions deepened and in order to create a safe anchorage for destroyers as well as submarines, the Camber was also deepened. In November 1913 the Camber was formally designated a torpedo centre with a repairing depot that came into use on 22 May 1914. Storage for oil fuel at the Eastern Dockyard was increased and Langdon prison, on the Eastern cliffs overlooking the harbour, was converted into Naval Barracks.

On 14 July 1912, at Long Reach near Dartford Joyce Green Airfield was opened by Vickers Limited, for use as an airfield and testing ground. The site had been chosen by inventor Hiram Maxim (1840-1916) who, between 1883 and 1885, had founded an arms company to produce automatic guns that used gas, recoil and blowback methods of operation. The Maxim automatic gun was patented and, with financial backing from Edward Vickers (1804-1897), Maxim produced his machine gun at a factory in Crayford, Kent. At the outbreak of World War I Joyce Green aerodrome became an ‘air defence’ airfield to protect London from bombing raids by Zeppelins as part of a ring of ten aerodromes around the City. One of the first occupants was No. 10 Reserve Squadron with a variety of aircraft. The unit also provided pupils from preliminary training schools with the final training in order to get their ‘wings’ before being posted to the Front. Each course of 20 pupils lasted two or three weeks and during that time, the pupils spent time at Lydd, Kent, where aerial gunnery was practised at the Hythe Range. Of note, during the War Maxim’s automatic gun was the standard weaponry of the British Army.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965), on 25 October 1911, was appointed the First Lord of the Admiralty (1911-1915), and from the outset expressed his concern about Germany building up her military strength. In Germany from 1898, with the active support of Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888-1918) the German Empire had passed four separate Flottengesetze – Fleet Laws or Naval Laws, one in 1900 then 1906 followed by 1908 and the last one in 1912. On land, Germany had created the Heer by combining ground and air assets into an integrated force. This was to protect herself in the event of an invasion from France in the west and Russia from the east. In 1905 the German Army Chief of Staff, Alfred von Schlieffen (1833-1913), had taken this one step further by drawing up a plan based on taking the offensive against the perceived attack. First against France, quickly beating her and before Russia had a chance to mobilise her armed forces Germany would attack that country. To fulfill the Schlieffen plan, Germany began to build up her military and aeronautical strength or Heer. While at sea, the German Secretary of State for the Navy or Kriegsmarine, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930) was committed to building up a force capable of competing against the Royal Navy. To gain information on what was happening in Germany, Churchill created the Naval War Staff whose role was advisory providing ‘with the accuracy of the facts on which that advice is based.’ Churchill also visited naval stations, dockyards and aircraft factories at the same time as successfully campaigning in the cabinet for the largest naval expenditure in British history.

Frederick Bernard Fowler was born in Lewes, East Sussex in 1883, the son of a farmer. He started his training as an engineering draughtsman, possibly at Callender’s Cable & Construction Company, Erith Kent, that specialised in the manufacture of cables. He then joined Vickers, Sons and Maxim and showed a particular interest in the internal combustion engine of their 20-horse power Thorneycroft car. After five years Fowler joined the Climax Motor Company in Coventry but his interest in aviation was aroused by Blériot’s cross-channel flight in 1908. Moving to Eastbourne, Fowler, while working as a consultant engineer bought a single-seater Blériot Anzani from William Edward McArdle (1875-1935). He taught himself to fly, gaining RAeC certificate on 16 January 1912. Fowler then leased a 50 acre site to the west of St Anthony’s Hill, Eastbourne for a proposed airfield and flying school from Victor Christian William Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire (1868-1938). McArdle was opening East Boldre aerodrome and flying school at Beaulieu, near Lymington, Hampshire, (see below) and he advised Fowler on the pros and cons of opening and running a flying school. McArdle allowed Fowler to use the hangars and airfield at Beaulieu while Fowler’s airfield and hangars were being constructed. At the beginning of December 1911 Fowler opened the Eastbourne Aerodrome and Flying School.

Eastbourne aerodrome had a 580 yard long runway made of wooded boards covering the intervening drainage ditches. It also had spacious hangars, well-equipped workshops and on the foreshore hangars to accommodate seaplanes. With 2 mechanics and a fleet of 3 aeroplanes, one of which was a seaplane, Fowler’s flying school opened. Pupils were taught to fly both types of planes being charged an ‘inclusive fee for tuition in one type £65 for aeroplane and £90 for both types.’ However, Fowler soon found teaching in single-seater aeroplanes both time consuming and expensive so he bought a Bristol Boxkite two-seater directly from Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton. This was the first aeroplane to be built at Filton, for which he paid £280. Both the Flying School and the Aerodrome were profitable with Fowler continuing to expand his fleet including buying two more Boxkites. In early 1913, with the financial backing provided by Charles W de Roemer (1887-1963), Fowler joined forces with Frank Hucks Waterplane Co to form the Eastbourne Aviation Co. Ltd (EACL). They opened an aircraft factory to produce B.E.2c and Avro 504 aeroplanes. At about the same time the Admiralty leased part of the Eastbourne airfield and at the outbreak of War the RNAS took over the factory, airfield, the flying school and subsequently neighbouring land. Fowler joined the RNAS and following the amalgamation of the RNAS and the RFC into the RAF in 1918, Eastbourne Aerodrome became the training station of day bombers. At the factory, besides the aircraft already in production they also made Bristol F.2B, Airco DH.6, Airco DH.9 and Sopwith Camel. After the War the ownership of both airfield and the factory returned to EACL. They closed the airfield and the factory diversified into building motorbus bodies as well as aircraft employing 60 people. However, orders subsequently declined and the factory closed in 1924.

Members of the Aero Club at Royal Engineers Balloon Factory, Farnborough Common, Hampshire 1909. Wikipaedia

Between 1904 and 1906, the Army Balloon Factory together with the Army School of Ballooning, both of which were under the command of Colonel James Templer, moved from Aldershot to Farnborough Common. The name Balloon Factory was a misnomer for the remit was research, experimentation and evaluation of different types of balloons, airships and war kites. Production of successful projects were passed to the private sector that gained concessions through bidding. Typical of such a project were war kites produced by Samuel Cody’s. They were winged box kites capable of carrying a man and were of particular use in meteorology and for reconnoitering. Templer was due to retire 1906 and a new Superintendent (1906-1909) John Edward Capper (1861-1955) was appointed. However, at the time of the Templer-Capper handover, Templer was involved in the development of Britain’s first military airship the Nulli Secundus (‘second to none’) by the Balloon Factory, so stayed on until this development was completed. As the new century dawned in Germany, Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917) made the first flight of his twin Daimler engine, aluminium framed rigid airship, the Zeppelin LZ1, over Lake Constance in southern Germany. The airship remained in the air for 20 minutes but was damaged on landing. Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873-1932), at about the same time, was experimenting with petrol engine driven non-rigid airships. He designed, built and flew around the Eiffel Tower in his first powered airship and won the Deutsche Prize in 1901.

Nulli Secundus Dirigible No 1, semi-rigid airship. Britain’s first military aircraft that flew on 10 September 1907. IWM

Templer went to Paris, visited Santos-Dumont and compiled a report on his return in which he recommended that further research should be undertaken into airships. Consent was given and in 1904 work began on the first British airship, the 55,000 cubic feet Nulli Secundus. The following year, to coincide with the move to Farnborough, the airship’s shed was completed. On 10 September 1907, the Nulli Secundus inaugural flight took place from Farnborough common, not far from the Balloon Factory and was scheduled to fly over London. However, due to strong winds the Nulli Secundus was forced down and seriously damaged. Three weeks later, on 5 October, the flight was again attempted with Capper and Cody at the helm. While over London increasing wind forced her down, she was moored at Crystal Palace and eventually returned back to Farnborough. The Nulli Secundus design was scaled down and on 1 May 1909 the experimental airship, Nulli Secundus II or Baby was launched. Like the parent airship she was not a success but following modifications including a larger envelope Beta proved to be successful. She took part in Army exercises and proved that she was able to stay aloft for almost eight hours. Following which, unusually, both Beta and the Army’s third airship Gamma went into production at Farnborough.

Samuel Cody worked on the development of Britain’s first military aeroplane, British Army Aeroplane No.1. The first flight of which took place at the newly laid Farnborough Airfield on 16 October 1908. Although the flight ended in disaster for the aeroplane Cody started work on British Army Aeroplane No.2 as well as working on the Mayfly airship. Fellow aeronautical engineer in 1908-9, John Dunne, was working on secret experiments in Glen Tilt, a flat area of land in the Grampian Mountains owned by John George Stewart-Murray, Marquis of Tullibardine (1871-1942). The Marquis was an Army friend of Capper and in 1908 Blair Atholl Airfield was laid for the projects. There, Dunne developed a man-lifting glider – almost certainly a monoplane – and a tailless biplane. In 1909 Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928) the Secretary of State for War (1905-1912) was instrumental in setting up the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (1909-1979). This was to ‘provide the aircraft industry with a sound body of science on which to base the development of aircraft.’ Shortly after funding was withdrawn on Cody’s aeroplane project and all of Dunne’s projects. Haldane, in October 1909 appointed Mervyn O’Gorman (1912–1916) as the first civilian Superintendent of the Balloon Factory, replacing Capper. However, Capper did remain the Superintendent of the Army Balloon School but his post was of short duration for in February 1911 it was announced that the Balloon Section, School and Factory were to be replaced. They then became the Air Battalion of the Corps of Royal Engineers and the Balloon Factory was restyled as the Army Aircraft Factory.

The British media, at the close of 1911, were reporting that other countries were actively developing their air armoury including the setting up of specialised defence divisions within their armed services. Germany that saw the future in airships, had twenty officers and 465 men in their air service. France had 8 airships, 10 aeroplanes, 24 officers and 432 men in their specialised air division. While the US had set up the American Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps, the 1st Aero Squadron having 29 factory-built aircraft. Back in February 1909, the Aerial Navigation sub-committee of the Committee for Imperial Defence recommended that all government-funded heavier-than-air experimentation should stop. Sir William Nicholson (1845–1918), the Field Marshal Chief of the General Staff 1908-1912, was quoted as saying, ‘aviation is a useless and expensive fad advocated by a few individuals whose ideas are unworthy of attention.’ On 29 September 1911, the Italo-Turkish War broke out between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire. The war lasted 13 months and both sides used aircraft for reconnaissance and aerial bombardment. Realising that progress in aviation, including specialist trained forces to fly and to look after machines, the lack of an air armoury could no longer be ignored. Sir William Nicholson wrote, ‘It is of importance that we should push on with the practical study of the military use of air-craft in the field… (And the) training of men … in view of the fact that air-craft will undoubtedly be used in the next war, whenever it may come, we cannot afford to delay the matter.‘ In November 1911 the Committee for Imperial Defence set up a sub-committee to examine the question of the future of military aviation.

Eastchurch sculpture depicting a Short Brothers biplane. Unveiled 2009 to commemorate the centenary of British aviation. Grindtxx

The first Naval Flying School was established at Eastchurch in December 1911 due to the persistence of Francis McClean. It was he who had joined forces with the Short brothers by providing the land at Leysdown and Eastchurch for an airfield and an aircraft production factory. At the end of 1910 he offered both the Admiralty and the War Office aircraft and the Eastchuch airfield to teach naval and military personnel to fly heavier-than-air machines. Even though the RAeC offered its members as instructors the War Office declined though the Admiralty accepted. Of note, in the US, aviator Eugene Burton Ely (1886-1911) on 18 January 1911 had landed his Curtiss pusher aeroplane on a platform on the armoured cruiser USS Pennsylvania. The plane was stopped using the tailhook system designed by aviator Hugh Robinson (1881-1963). It was this feat that aroused the interest of the British Admiralty that set in motion McClean’s ambition.

1912

The sub-committee that was set up in November 1911 to examine the question of military aviation, reported on 28 February 1912. They recommended the establishment of a Flying Corps made up of a military and naval wing with a central flying school and an aircraft factory. The recommendations were accepted by Parliament and on 26 March 1912, George V (1910-1936) gave his approval to the title ‘Royal Flying Corps’ (RFC). This received Royal Assent on 13 April 1912. The RFC consisted of a Military Wing administered by the War Office and a Naval Wing supervised by the Admiralty and by the terms of its inception, the Admiralty were permitted to carry out experimentation at its flying school at Eastchurch and shortly afterwards full permission was ratified.

The RAeC offered the Royal Navy two aircraft to train the first pilots and the first training course began on 2 March 1912. The Admiralty advertised for unmarried officers, who were able to pay the membership fees of the RAeC, to apply and two hundred did! Four were accepted and these were Lieutenant Eugene Louis Gerrard (1881-1963) who eventually became an Air Commodore. Lieutenant Reginald Gregory (1883 -1922) who worked with RNAS Armoured Car Division in Belgium and Russia. Lieutenant Arthur Murray Longmore (1885-1970) who eventually became an Air Chief Marshal and Lieutenant Charles Rumney Samson (1883-1931) who was the first pilot to take off from a ship underway at sea (see below) and eventually he too became an Air Commodore. Prior to the beginning of the course, the chosen officers received technical instruction at the Short Brothers aircraft factory and visited French aeronautical centres. A concomitant of the Naval Training School was close to the location of the Eastchurch Short aircraft factory. There, significant developments were taking place including production of folding wing aeroplanes for use aboard aircraft carriers. These days, Francis McClean’s gift is seen as the start of the RNAS.

Ark Royal – the first ship designed and built as a seaplane carrier. War Department Central News Photo Service 1918

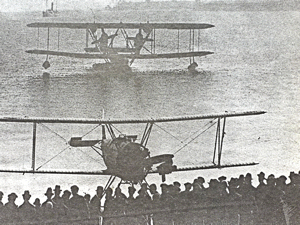

The Home fleet was restructured and came into force on 1 May 1912 when HMS Hibernia was based at the Nore. This was the naval command for the Thames estuarine area of south east of England and the Nore’s base was the naval port of Sheerness. The Hibernia was a Royal Navy King Edward VII Class pre-Dreadnought Battleship commissioned in 1907 fitted with a temporary runway on the foredeck. This consisted of a trolley-shuttle system ramp that stretched over her forward 12 inch guns from the ship’s bridge to bow. She went to sea on 9 May 1913 and on board was a Short S.38 T 2 floatplane (later called a seaplane) modified by air-bag floats as well as wheels. Charles Samson, one of the first four naval officers to be chosen to attend the Naval Training School, agreed to undertake the experiment. While the ship was underway Samson took off along the ramp and both the launch and the subsequent landing on water were successful! The Royal Navy cruiser Hermes had been adapted as a seaplane carrier and under the command of qualified pilot Captain Gerald William Vivian (1869-1921) she was ready to start undertaking trials. These proved successful but at Christmas 1913 the War Office stopped the project. Nonetheless, the Admiralty, who had been impressed by the Hermes trials, procured the Ark Royal that was being built by Blyth Shipping Company, Northumbria. Following instructions by Vivian and his team the Ark Royal was modified and as a seaplane carrier the Ark Royal was launched on 5 September 1914.

In 1912 a total of 211 pupils were being trained at the various private flying schools around the country. The largest number of these establishments were at Brookland, Hendon and on Salisbury Plain. Flying schools at Eastchurch and Upavon trained 31 pupils that year and Eastbourne 6. The other schools were at Freshfield, Farnborough, Fairlop and Windermere. The pupils were a mixture of military and naval officers as well as civilians all of whom paid for the course themselves but very few could also afford to pay to take the RAeC exam. The construction of the Central Flying School began on 19 June 1912 east of Upavon village not far from Larkhill at the edge of the Salisbury Plain.

Members and Staff on the Central Flying School’s first course at Upavon. Capt Godfrey Paine RN is seated in the front row, at the centre Major Hugh Trenchard standing in the second row extreme right. Air Publication 3003

The first commandant was Naval Captain Godfrey Marshall Paine, (1871-1932) with Major Hugh Montague Trenchard (1873-1956) his assistant and ten Staff Officers. Paine had commanded torpedo schoolship HMS Actaeon when the first four naval officers who learnt to fly, Lieutenants Gerrard, Gregory, Longmore and Samson spent time there. Throughout their training, Paine had taken a keen interest in their progress and both Paine and Trenchard had learned to fly in order to take up the posts. However, although Trenchard was not a good pilot he excelled at organisation and thus, he ensured that the Central Flying School trainee pilots were well-versed in map reading, signalling and engine mechanics. Later Trenchard became known as the ‘father of the Royal Air Force’. From the outset, eighty flying students were taught on each Central Flying School course which lasted for sixteen weeks. The students did not pay for the course nor to take the RAeC exam as long as their instructors sanctioned them applying. In December 1912, 32 officers graduated with RAeC certificates.

From the outset, the Military Wing consisted of three squadrons each commanded by a Major. It was also recognised that squadrons in the field would need dedicated support beyond that provided by the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. This was assigned to the Line of Communications Workshop, later to become the Flying Depôt then at the outbreak of World War I ‘the Aircraft Park’. During this time, the Army’s Balloon Section of the Royal Engineers had been increased to two companies. Number 1 Balloon Section for balloons and airships and Number 2 for aeroplanes. Together they formed the basis of the Military Wing of the RFC founded on 13 May 1912. The Army Balloon Factory on Farnborough Common was renamed the Royal Aircraft Factory employing it’s first aeroplane designer, Geoffrey de Havilland (1882-1965)

In 1912 the Superintendent of the Royal Aircraft Factory (RAF) at Farnborough was Mervyn O’Gorman, a post he held until 1916 when engineer Henry Fowler (1870-1938) succeeded him. By this time the RAF was heavily involved in manufacturing aircraft for use by both the Naval and Military Wings. A role it maintained until 1918, employing many notable aviation and aerospace engineers as well as designers, including Alan Arnold Griffith (1893-1963), Henry Philip Folland (1889-1954), Samuel Dalziel Heron (1891-1963) and John Kenworthy (1883-1940). By the beginning of World War I RAF had ready for production, two effective machines, B.E.2 = the Blériot Experimental – tractor or propeller – second layout, and the F.E.2 = Farman Experimental – pusher or propeller – second layout and in both cases their derivatives. By 1918 the RAF had eleven scientific departments researching into full-scale flight and all the other scientific, design and engineering processes that are needed to support safe and effective flight.

On 1 April 1918 the Royal Air Force was formed and to avoid confusion the Royal Aircraft Factory was renamed the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE). Under engineer William Sydney Smith (1866-1945), Superintendent from March 1918 to 1925, the RAE relinquished its manufacturing role to concentrate on aeronautical research. This, Smith stated, was to make its resources and the results of its work, readily available to the aircraft industry in general. However, due to the serious recession that struck Britain’s economy in the 1920s retrenchment of Government expenditure reduced funding to about 20% of its 1918 level. This forced Smith to reduce the number of employees from 5,052 in 1920 to 1,316 in 1922. That year, as part of the cut backs, the Biggin Hill Wireless and Photographic Departments were transferred to Farnborough. In 1924 further savings in funding were proposed and the Halahan Committee was formed to report ‘what steps, if any, should be taken to reduce the cost without impairing its value as an experimental establishment in peacetime or its capacity to expand in an emergency’. They concluded that ‘The primary function of the Establishment is that it should provide a full-scale aeronautical laboratory for the Air Ministry.’ The Committee went on to list a number of activities that the Establishment could undertake but these remained unaltered other than the Establishment had to keep a close eye on expenditure and to find innovative ways of getting round financial inconveniences.

Memorial commemorating Samuel Cody’s first flight, Farnborough Road (A325) overlooking the airfield.

This was the remit of the Establishment at Farnborough until 1988 and proved to be both successful and financially viable. On 1 May 1988 the RAE was renamed the Royal Aerospace Establishment and the following year Farnborough housed the first civilian operations In 1991 the Ministry of Defence decided that the airfield was surplus to military requirements and should be redeveloped as a business aviation centre. The history of Farnborough airfield, on Farnborough Common, goes back to 1908, the year it was especially laid for Britain’s military aeroplane’s first flight, designed and piloted by Samuel Cody (see above). A grassy area south of the Balloon and Airship sheds at Farnborough Factory was used and following the 1924 Halahan report it’s use was specifically for looking at and dealing with problems associated with airfield runways. For instance, in the early days one of the many problems facing pilots was not being able to see the runway when trying to land, hence thought was given to runway lighting by the Establishment. A survey in the 1930s showed that even where civil airfields had installed high intensity lights, in the UK, US and Europe, accidents still happened. During WWII runway lighting was banned except in the US where experiments continued but remained fraught with problems.

In 1946, in Britain, the problem was passed to Farnborough, specifically to Edward Spencer Calvert (1902-1991). He had designed and specified the use of the spotlights that enabled the bombers of 617 squadron to carry out the attack on the Rhur dams in May 1943. Calvert, helped by another Farnborough researcher, John Sparke took up the cajole. Backed by simple practical simulations they attempted to ascertain the visual and mental processes by which a pilot lands an aircraft. They then developed a theoretical model by which different lighting systems could be compared, and tested the theoretical results using simulation on a cyclorama, a panoramic image on the inside of a cylindrical platform designed to give viewers standing in the middle of the cylinder a 360° view. This demonstrated conclusively that the mental processes by which visual judgements on the present position of the aircraft, aiming point and the rate of change of position were extracted from the changing perspective of lighting patterns. They aimed to provide smooth transition from instrument to visual flying without optical illusions, and to provide sensitive and natural indications which could easily be interpreted by the average pilot. The approach lighting pattern should consist of a centre line of light with horizontal bars of light running transversely across it at even intervals. This pattern consists of two basic elements – a line of lights leading to the runway threshold, and horizontal lights to define the altitude of the aircraft. Calvert was the first to realise that it was easy to confuse lateral displacement with angle of bank so placed much stress on roll guidance.