Stylised drawing showing the Roman Classis Britannica, Pharos on the eastern and Western Heights and Roman harbour. Dover Museum

It was probable that the indigenous mariners of Dover played a significant role in the defence of Britain from invasion by the Saxons, in the time of the Roman occupation. Long before the Romans had established the large Classis Britannica on the western side of what is now Market Square, Dover, followed by the larger Shore Fort. The Romans had also built Dover’s first harbour, to the east of the forts in the estuary of the River Dour. Following their departure, King Wihtred (c 690-725) had a wall built across the Dour delta to protect his newly established Canons at St Martin’s monastery from sea robbers. Within this protection a harbour was created on the eastern side of Dover Bay that was fed by the River Dour. The harbour was approached through Eastern Gate, which stood about 75-yards west of the site on which old St James Church was subsequently built.

This harbour remained on the eastern side of the town for more than a thousand years and was possibly used by Alfred the Great (849- 899). In 897, he had a number of ships built each of at least 60 oars, to counter Danish Viking raids along the south coast of England. These ships were seen by later historians, as the foundation of the Royal Navy and Alfred’s fleet won a significant victory in the Battle of Stourmouth, in East Kent, in the Wantsum Channel, at Plucks Gutter. Following Alfred’s death the ‘navy’ was abandoned and except for frequent maritime skirmishes from potential invaders, Dovorians busied themselves with cross-Channel traffic and fishing for herrings, the country’s main staple food. The quay, at this time, was probably where King Street is now.

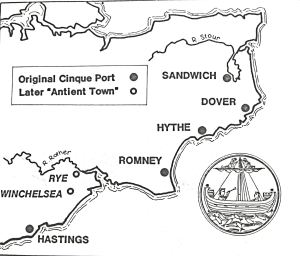

Dover, situated at the southeastern tip of the British Isles is the closest seaport to the Continent. It is on the English Channel – an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that joins the North Sea off the Thames Estuary. The Channel is about 350 miles long, varies in width from the narrow Strait of Dover (French: Pas de Calais) 22 miles to 150 miles further west. The Channel is a relatively shallow sea with an average depth of about of about 148 feet in the Strait and 390 feet at its widest part. Because of this, it acts as a funnel to both winds and tides, making the Strait notoriously tempestuous. In consequence, the ships built by the mariners of Dover and the other ports along the Strait were strong and the mariners competent seamen. Further, the mariners of three ports had loose amalgamation. These ports were, Dover, Sandwich and Limme – as it was called in those days, Lympne these days and at that time it was on the coast. Calling themselves Portsmen, the affiliation was fostered by long trips to the fishing grounds of the North Sea.

Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) recognised the capabilities of these mariners and also the strength of their ships. It was also evident to him that the ports were in an excellent strategic position from a military and naval point of view. In consequence, Dover in 1036, was the base for the royal fleet and in 1041 the King officially augmented his fleet by giving the Portsmen a much-prized Charter. This stated that they were to provide Ship Service, that was to provide 20 ships, manned with 21 men for 15 days a year. To comply with the Ship Service Dover was divided into 20 wards with each ward providing a fully crewed ship. At different periods of time the number and names of the wards changed and by 1429, when the names were fully recorded, there were 21 wards: Bekyn, Burman, Bully’s, Canon, Castledene, Derman, Delfys, Deeper, Halfguden, Horsepol, Moryns, Nankyn, Ox, Snargate, Syngyl, St Mary, St George, St Nicholas, Upmarket, Werston and Wolvys. The role of the Portsmen manning the ships was to protect the coast and to provide cross Channel passage of troops needed to defend English possessions in France. In return the King gave the three towns rights and privileges.

Long before Edward the Confessor came to the throne, Dover’s mariners who worked the passage – carrying people, animals and cargo between England and France – had formed the Fellowship of the Passage. When not working the passage they were fishermen but of more importance, they were all Freemen and with their contemporaries in the other two towns, it was they who provided the ship service. Therefore, it was for them that privileges in the Charter were given. These privileges were the titular rank of Baron and the right of personal liberty (passage), free carts (freedom of movement), freeland (freehold) and free trade.

Edward also appointed Godwyn, the Earl of Wessex (1001-1053), the father of his wife Edith (1025-1075), the Lord Protector of Dover, Constable of the Saxon Castle and Earl of Kent. Although loyal to the King, Godwyn, at the time, was becoming increasingly angry at the growing Norman influence that Edward was fostering. In 1048, Eustace II, Count of Boulogne (c1015-c1087), demanded of the Dover Portsmen, the feudal right of droit de gîte – the forcible possession of lodgings that best pleased him. This was against their Chartered rights and therefore they refused. An altercation ensued in which Eustace’s men came worse off and Godwyn spoke up on behalf of the Dovorians, which the King accepted.

However, in 1051, Edward received Eustace at his court with great honours and shortly afterwards there was a second violent clash between the people of Dover and Eustace and his army. Seven townsfolk were killed though Eustace lost twenty men. Edward ordered Godwyn to punish the townsfolk but he refused and for this, Godwyn and his family were exiled from the Kingdom. That was in September 1051 but before the year was out, Edward again appointed Dover as the base for his royal fleet. The following year Godwyn returned with armed forces and much to Edward’s surprise, the Portsmen supported Godwyn. Edward was obliged to restore Godwyn’s titles and allow Dovorians to defend the town as of right. Godwyn died on 15 April 1053 and his son Harold succeeded him to all his titles, including Lord Protector of Dover and Constable of the Saxon Castle.

Harold took these roles as seriously as his father and finished Dover’s main military fortification, the Castle. Many years before a Saxon Castle had started to be erected on the top of the Eastern Heights and Harold had a Saxon Keep and towers built. In 1064-65 he allied himself and the Portsmen with William, Duke of Normandy (b 1028). This was against William’s enemy Conan II, Duke of Brittany (1033-1066). For this, William knighted Harold and presented him with weapons and arms in return, according to the Bayeux Tapestry, Harold swore to support William in his claim to the throne of England. However, it has been suggested that the patron of the Tapestry, Eustace of Boulogne had used his influence to have this put in! There are also various accounts of Edward the Confessor promising William the crown of England.

In 1062-3, with the help of the Portsmen it is said, Harold conquered Wales and two years later subdued a major rebellion in Northumbria. For these and other reasons, Edward named Harold his successor and this was confirmed at the sitting of the Witanagemot on 5 January 1066 – the day that Edward the Confessor died. Harold was crowned King but his brother Tostig (d1066) and King Harold II of Norway (d1066), the latter laying claim to the throne, invaded. Having defeated them at Stamford Bridge, Yorkshire, on 25 September 1066, Harold and his army, which included Portsmen, marched south. The news reached Harold that William and his forces had set sail from Normandy and the army put a spurt on. William arrived at Pevensey, East Sussex, on 28 September 1066 and following Harold and his army’s arrival, the famous Battle of Hastings took place nearby. That was on Saturday 14 October 1066 where Harold was killed and William was proclaimed the King of England (1066-1087).

Following the Battle, William I’s army marched east along the coast razing to the ground, villages and towns including the three Ports. In Dover, the monastery of St Martin that had been built on the site of the old Roman Shore Fort was ransacked and destroyed. William, a religious man, was angry and ordered the monastery to be rebuilt in a grander style. For sometime after, it was believed the Norman church of St Martin the Grand, was the most magnificent edifice of its type in England. From excavations, it is known that the monastic buildings stretched from what is now Market Square to Bench Street and reached the banks of the River Dour.

Not long after, East Kent came under attack from the Danes who were repulsed by the Portsmen and their allies from the ports of Hythe and Romney. This provided proof of loyalty to William and he drew up a new Charter. In this the stronger port of Hythe substituted that of Lymne while Romney, west of Hythe, was added, as the coast there was unprotected. Further, their mariners were well known for being as hardy and ferocious as those from Dover. Finally, Hastings was included, to the west of Dungeness point, in honour of his victory there. William also made Hastings the head Port and collectively, thereafter, these five Ports were called the Cinque Ports – pronounced ‘sink’. The Freemen of all these ports who provided ship service were called Barons and the Charter stated that the Cinque Ports Barons, and their heirs ‘do to us and to our heirs Kings of England yearly their full service of fifty-seven ships at their cost for fifteen days at the summons of us or our heirs.’

Throughout England, William introduced an entirely new legal system adopted from that established in Normandy. The Sovereign was head and laws were administered, if not by him in person, by judges appointed directly by and dependent upon him. William also effectively created palatinates and one was for Kent that included the Cinque Ports. The Kent palatinate was under his half-brother, Odo the Bishop of Bayeaux (d1097) and gave Odo extra special powers that included the head of the new Norman legal system. Odo used this and quickly proved himself to be despotic. One of his actions was to withdraw the Portsmen’s privileges and within a decade the hated Odo was deposed. This enabled Kent and the Cinque Ports to revert to aspects of the pre-Norman legal system that they liked and also, for the Portsmen, the reintroduction of William’s Charter.

The famous survey, the Domesday Book of 1086, confirmed the Charter and Cinque Ports importance in relation to the English Channel and the coast of mainland Europe. Indeed, the Kent portion begins: ‘Douere, in the time of King Edward, rendered eighteen pounds, of which moneys King Edward had two parts, and Earl Goodwyne the third … The Burgesses gave the King twenty ships once a year, for fifteen days, and in each ship were twenty-one men. This they did in return for his having endowed them with Saca and Soca.’ The Domesday book goes on to say that when the King’s messengers came to Dover for passage to France, the towns Burgesses provided a Pilot and an assistant to give the messenger and his horse passage. For this, the pilots were paid 2 pence in summer and 3 pence in winter. For anything else, the messenger had to pay out of his own pocket.

About the time of the Domesday Book another book was written strictly applicable to the Cinque Ports. This, apparently recorded details of William’s Charter and thereafter was like a diary giving accounts of the Cinque Ports jurisdiction, powers, financial contributions made and paid out in consequence of the Charter and subsequent Charters. Sadly, the book disappeared towards the end of the reign of Charles II (1630-1685) and, to date, has not been found. Ship service apparently dominated the entries.

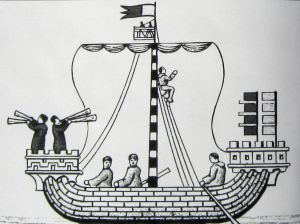

Cinque Ports Ship Townwall Street subway mosaics, note the sweep at the stern quarter. Alan Sencicle 2009

Herring fishing was also well covered in the book as an important industry to the Cinque Ports. The Portsmen built their own ships and in Dover this took place on the beach and were kept at sea except at times of danger or foul weather when they were hauled on to the beach. The ships were built as fishing vessels and, particularly in Dover, passage vessels. To convert them into warships for ship service, the Portsmen erected fore and stern castles and armed the crew. At the time, the ships did not have rudders; instead they were navigated by a sweep – a large oar – off the stern quarter. The size of the ships can be gleaned from the fact that twenty men pulled the oars and a large square sail propelled them.

William II (1087-1100) succeeded his father to the throne and the Cinque Ports men were equally as loyal to him. However, William I had divided his domains between his two sons giving the Duchy of Normandy to his elder son, Duke Robert Curthose of Normandy (c1051-1106) and William II, England. Robert wanted to unite the two countries with one ruler – himself, supported by Odo. An invasion took place with Odo seizing Pevensey Castle built by William I in 1088. The Portsmen supported William II and attacked. Odo was expecting Duke Robert to come to their aid but he failed to arrive. Odo and his men escaped to Rochester Castle but once there the Castle was held in a siege lasting six weeks by Royalist forces including Portsmen. When Odo and his men were finally released they were in a dreadful physical state and so were allowed to return to Normandy.

In 1090, the Portsmen went with William to France to claim Normandy and the following year to Scotland to stop an invasion. Battles subsequently ensued, most, of which the Portsmen were involved in. In 1100 the King died without issue and his younger brother, Henry (b 1068), was proclaimed King. At the time Duke Robert was on his way home from the 1st Crusade (1096–1099) and so Henry I (1100-1135), was crowned in haste on 5 August. In March 1101 Duke Robert invaded, by way of Dover, and the Portsmen fought back. He then moved further west along the coast to Portsmouth and in August that year the two brothers met at Alton, Hampshire. A negotiated settlement confirming Henry as King and controller of the English Channel averted civil war but the animosity was to remain for years to come.

To meet the needs of the Cinque Portsmen a single special court had been developed under the auspices of the King’s officers. Held at Shepway, near Hythe, the court dealt with cases that were considered beyond the jurisdiction of the five towns’ courts such as, treason, counterfeit, treasure–trove and naval service. It also gave the right of Appeal against judgements of town officers. The Shepway Court normally met once a year but could be summoned for a special meeting with forty days notice. Attendance by the Barons of the Cinque Ports was compulsory.

Henry I was involved in a number of altercations both in Britain and abroad, and on most occasions the services of Portsmen were called upon. In 1118, Maud, Henry’s wife died and on 25 November 1120, Henry’s only legitimate son, William, died in a shipwreck. Thus, in 1126 Henry appointed his daughter Matilda (1102-1167), as his heir. At the instigation of Henry for better relations with the French province of Anjou, she married the 15 year old Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (d 1151) in 1128. At the time the English Barons – no relation to Cinque Ports Barons – were very powerful in the country, owning great swathes of land on which they ruled from fortified castles that they had built or inherited. These Barons were the progeny of the Norman elite who had come over with William I and were subsequently rewarded with the domains. Thus they were a major force in English politics and although they had initially agreed to Matilda being Henry’s successor, following the marriage they changed their allegiance to Henry’s nephew, Stephen of Blois (b circa 1092). Stephen had married Maud (sometimes called Matilda) of Boulogne (c1105-1152) who was the first cousin of Matilda on her mother’s side. Maud was also the granddaughter of Eustace II of Boulogne, her father being Eustace III who had supported Duke Robert Curthose’s claims to the English throne.

Henry died in December 1135, while Matilda was on the Continent and Henry’s nephew, Stephen, speedily crossed to Dover to claim his right to the throne as the male heir in accordance with the custom in Normandy. However, he found Dover Castle closed to him by the Constable, John de Fiennes with the Portsmen supporting Fiennes. Nonetheless, with the support of the Barons, Stephen marched to London, seized the throne and the treasury. On 22 December 1135, Archbishop William Corbeil (1070- 1136) crowned Stephen and Maud at Canterbury Cathedral. The Archbishop had been the instigator for the demise of Dover’s beloved great monastery, St Martin-le-Grand, much to the annoyance of the Dover Portsmen. Matilda landed in Dover with an army in March 1136 but even though Fiennes was a relation, she avoided the Castle and went to Canterbury.

In 1138, while Stephen was fighting Matilda’s army in the Midlands, Maud advanced into Kent and demanded the surrender of the Castle. John de Fiennes was fighting alongside Matilda, having left his deputy, Walkelin de Magimnot in charge. He surrendered the Castle to Maud. At the Battle of Lincoln in April 1141, Stephen was captured and imprisoned. Matilda, taking the Saxon title of ‘Lady of the English‘, briefly ruled, with the support of the Cinque Ports. Meanwhile, Maud had rallied support and Stephen was eventually released. On regaining the throne, Stephen, in 1147, sent the Cinque Ports Fleet to help in the siege of Lisbon (1 July – 25 October) with the promise of plunder and thereby getting them out of the way.

The civil war continued and in 1147 Matilda’s son, Henry (b 1133), raised a small army of mercenaries and invaded England. The Cinque Ports fleet were still in Portugal. Nonetheless, Walkelin Magminot capitulated Dover Castle! In January 1148 Matilda abandoned her claim to the English throne and the Castle was eventually returned to Stephen. In 1152, Stephen appointed his son Eustace (1129-1153), Constable of the Castle with Magminot as his deputy. At about the same time, Stephen persuaded a few powerful Barons to support Eustace as his heir to the throne of England. His wife Maud had died on 5 May 1152 but then the following year Eustace died. They were both buried at Faversham Abbey that Stephen and Maud had founded. Following Eustace’s death an uneasy compromise was reached whereby Stephen would remain King but on his death, he was to be succeeded by Matilda’s son, as Henry II (1154-1189). Stephen died at Dover Priory on 25 October 1154. His body was taken to Faversham and buried next to his wife and son.

Although the Cinque Ports had provided a naval fleet for England from the days of Edward the Confessor, the politically astute Henry II issued a Charter in 1155 that formally recognised the Fleet as the nation’s naval force. The Charter stipulated that the Cinque Ports was to provide 57 ships crewed by 21 sailors apiece and to maintain the ships ready for the Crown in case of need. In return, the towns received ‘Exemption from tax and tallage. Right of soc and sac, tol and team, blodwit and fledwit, pillory and tumbril, infangentheof and outfangentheof, mundbryce, waives and strays, flotsam and jetsam and ligan’

In other words, they were exempt from tax and tolls and had the right of self-government, permission to levy tolls, punish those who shed blood or flee justice, punish minor offences, detain and execute criminals both inside and outside the port’s jurisdiction, and punish breaches of the peace. They had the right of possession of lost goods that remained unclaimed after a year, goods thrown overboard, and floating wreckage. They were also given the right of the King’s Truce when, from the Festival of St Michael (29 September) to St Andrew (30 November), the citizens were immune from arrest for debt or civil actions.

To enable the Cinque Ports to carry out the services required by Henry and his successors, the new Charter allowed the Ports to incorporate, or take over the administration of other towns. These were called ‘limbs and liberties’ and enjoyed many of the privileges afforded to the Head Ports. The liberties were usually villages near the Cinque Port while the Limb’s were towns further afield and far greater demands were made on them. To make sure that Limbs contributed to the Ship Service a Deputy was appointed by the Head Port to govern them. He could summon the inhabitants for any purpose to appear at the appropriate body in the Head Port. This ranged from crimes to the renewal of hostelry licences but the Deputy did not have the power to take independent action. There were two types of Limbs, incorporated and unincorporated. The corporate members were those whose membership was conferred by Royal Charter and they shared many of the Head Ports privileges. The unincorporated members were associated with their Head Port by private agreement and did not share any of the privileges. At the time, Hastings had fourteen Limbs, Romney five, Hythe one, Dover three and Sandwich five. It was in this Charter that the Court of Shepway was recognised.

Henry II’s political astuteness pervaded everything he did. Through the marriages of two of his four legitimate sons and diplomacy he gained possession of most of the west coast of France. The marriages of his three daughters brought him political influence in Castile, Germany and Italy. However, his personal relationships were appalling, notably with his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine (c1122-1204). She was the former wife of Louis VII of France (c1137-1180) and she and Henry had married only two months after her divorce. The reasons given for the divorce was that she and Louis were too closely related but she and Henry were as equally related! Henry’s relationship with his four legitimate sons, Henry (1133-1189), Richard (1157-1199), Geoffrey (1158-1186), and John (1166-1216) were disastrous. The King famously fell out with his close friend and companion, Thomas Becket (c1120-1170) and not so famously, but of great consequence to the Cinque Ports, was Henry’s relationship with Louis of France. At best, this was ambiguous.

Immediately on ascending the throne, Henry had set about regaining control of his grandfather’s domains on the Continent that had been lost during the Stephen/Matilda wars. Thus the Cinque Port fleet was employed to the full but even with the help of the Limbs there were mixed consequences. When involved in action, the Portsmen amassed fortunes from pillage, part of which they paid to Henry, but in between times their expenditure on Ship Service out weighed payments received from Henry. The King reached an uneasy peace in January 1169 which enabled the Portsmen to return to the steadily lucrative herring fishing. However, the year before, Henry had started to build a great fortification that could be seen from the coast of France, the impressive Dover Castle that can be seen today.

Started in 1168, during the following six years the Castle on the Eastern Heights began to take shape. This required many thousands of tons of stone. Most of which was were hewn in the Boughton Monchelsea quarries about three miles south of Maidstone on the River Medway. The stone was then dragged to the River on sledges and loaded onto Cinque Ports ships. The heavy cargo was then brought round to Dover’s harbour below the Eastern Heights. Ragstone was brought the same way from the Folkestone area, as was Caen stone from Normandy. From the harbour the stone was hauled up the steep hill to the site on sledges drawn by oxen. The ships used, were specially built by the Portsmen for the purpose and were larger than their fishing/fighting ships, requiring fifty oars and larger square sails, on a single central mast. The time spent building the ships and hauling the masonry to Dover was less time than that of the main source of income, fishing.

Following the building of the Castle, Henry continued with his altercations in France and frequently called upon the services of the Cinque Ports Fleet to transport him, his court and his soldiers across the Strait. One such journey, in July 1170, was to Fréteval, in the Loire Valley to make peace with Thomas Becket, his exiled Archbishop. The Archbishop returned by way of the Cinque Port of Sandwich on 1 December and went straight to Canterbury Cathedral but very quickly had another clash with Henry. The story of what happened next is well covered elsewhere. Suffice to say that on the afternoon of 29 December 1170, Archbishop Becket was in conference with, amongst others, Richard a monk from Dover. Four of Henry II’s knights – Reginald fitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton, entered the Cathedral and murdered Becket.

Afterwards, Richard the monk arranged for the immediate burial of the Archbishop and three years later Becket was Canonised. However, his replacement as Archbishop had not been appointed and Henry proposed the quiet, mild mannered, Richard of Dover. This was met with strong opposition from within the English Church but on 7 April 1174, Pope Alexander III (1159-1181) consecrated Richard as Archbishop of Canterbury. He was also appointed Alexander’s Legate – judge for the papacy. Following Archbishop Richard’s return to England he was enthroned at Canterbury on 5 October. During that year Canterbury Cathedral was destroyed by fire and subsequently rebuilt in the Gothic style we see today.

Henry continued to regularly call on the services of the Cinque Ports Fleet, usually to deal with territorial problems in France instigated by at least one of his sons. These, in turn, led to tensions with Louis and the demands on the Portsmen increased. To help them provide Ship Service, in 1190 the ports of Rye and Winchelsea were added by Charter to the original five ports. The two ports, known as the Antient Towns, were granted equal status to the Head Ports and the full title of the Confederation became The Cinque Ports and the Two Antient Towns.

Worn out by endless quarrels and battles, Henry died in July 1189. He was succeeded by his third son Richard, the older two sons having died. Henry’s death was possibly unexpected, for Richard had already declared his intention of joining the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Regardless of becoming King, Richard came to Dover to assemble his forces and on 1 December, before embarking, he signed a new Charter for the town. When he left for the Holy Land, his forces consisted of 4,000 men-at-arms, 4,000-foot soldiers, and a fleet of 100 ships, some of which were part of the Cinque Ports Fleet. To enable him to join the Crusade, Richard sold official posts to the highest bidders. The most senior civil post in England was that of Chancellor, who would also act as Regent while the King was away. William Longchamp (d 1197), from Normandy paid £3,000 for the privilege.

During his return to England, following the Crusade, Richard was captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria (1177-1194) and then held for ransom by the Holy Roman Emperor – Henry VI (1191-1197). Longchamp negotiated a ransom payment of 100,000 marks, drawn from the English coffers, with large contributions from Richard’s mother’s and John’s purses, amongst others. Richard was freed on 4 February 1194 and the pair returned to England through Sandwich. While Richard was in captivity, Longchamp had been relieved of his power by Richard’s brother John, over which the King was none too happy about.

Coronation Canopy being carried by Cinque Ports Barons at the Coronation of Charles I. LS Collection

While Richard was held hostage, John, recognising the major importance of the Cinque Ports realised that if he became King the loyalty of the Portsmen would be a valuable asset. To help gain their complicity he gave them, in Richard’s name, another privilege. That of the right of chosen Cinque Ports Barons to carry the gold Coronation canopy over the Monarch’s head in the procession from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey. At the subsequent banquet, he gave them the right to dine at the Royal table on the Monarch’s right hand side and afterwards they could have the canopy to be divided between themselves.

On his return to England, Richard named John as his successor and then lived up to his name Richard the Lion Heart over territorial disputes mainly against Philip II of France (1180-1223). These drew heavily on the already depleted English coffers that were causing unrest with the Barons as the onus could fall on them to relieve the country of debts. Hit by a crossbow arrow, Richard died on 6 April 1199 and John ascended the throne. He immediately, made a compact with Philip that brought two years of peace. Much maligned even today, John (1199-1216) faced formidable opposition from the religious and baronial establishments. The latter wanted full autonomy over their individual estates, castles and armies which John, in order to try and augment the country’s depleted coffers, increased taxation. In response, they wanted Philip of France to invade England in the belief that he would give them the autonomy they desired.

This had a direct effect on the Cinque Ports Fleet in their role as defenders, frequently engaging French ships and, on the whole, they were successful. It could be said that they took their role seriously, for not only did they sink many ships, they destroyed others in their own harbours on the pretext that they may invade. The Portsmen also pillaged French towns on the pretext that the percentage of the bounty given to the King helped to increase the country’s defences. The threat of invasion meant that John was obliged to finish the work on Dover Castle, including the completion of the Keep, most of the bailey and some of the curtain wall. These works required the services of the Portsmen to carry the materials in ships newly constructed for the purpose. Regardless of the share of booty that the Portsmen were giving to John, the Castle and other fortifications required money, which John was obliged to raise through more taxes.

As herrings were still a major part of the country’s staple diet and as the Portsmen were heavily involved in defending and raising money for themselves and John, they had to make the most of the time they had looking after their fishing industry. For centuries the Portsmen had been fishing off the East Anglian coast and at the time of Edward the Confessor had set up a base off the River Yare there. This had grown into a small town independent of the Portsmen but one of the privileges given in the Cinque Ports Charter of 1155 was to allow Portsmen to continue fishing off the River Yare. Sometime before, the Portsmen had encouraged the growth of an annual market in Yarmouth where they sold their herrings and administered. Because of the demands made on them to provide Ship Service, In 1205, John gave the Portsmen the right of den and strond – use of shore and quay – at Yarmouth. This effectively gave them the monopoly of all herrings caught there. The locals in Yarmouth objected and three years later they petitioned to have their own charter to regain some of their independence. However, John needed the Portsmen’s allegiance so he allowed them to retain the rights. This did not go down well with the citizens of Yarmouth.

In 1209 John appointed William of Wrotham (d 1217) ‘Custodes’ or ‘Keeper of the Galley’s’. He brought together the Cinque Ports Fleet with pressed merchant vessels to create effectively a ‘Royal Navy’. Changes in ship design were instigated including removable forecastles on both Cinque Ports and the other ships during combat. To pay for these and other expenses, John introduced judicial reforms that included fines rather than physical punishments. The reforms had a lasting, positive, impact on the English common law system while the fines were of great benefit to the coffers. However, they caused even more ill feeling from the country’s powerful Barons and so the threat of invasion increased.

The Portsmen, in 1214, took John and his military forces to France where he suffered an humiliating defeat. In consequence, at Runnymede, alongside the river Thames in Surrey, on 15 June 1215, the Barons forced John to put his seal on the Magna Carter if he wanted to retain the Crown. In essence, the document promised the protection of church rights and protection for the Barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice and limitations on payments to the Crown. Copies of the Magna Carta were sent all over the country including the different Cinque Ports and their Limbs. Hubert de Burgh (1170-1243), the Constable of Dover Castle, put the Dover copy in safe keeping at the Castle – so safe it was not rediscovered until 1630! It is now in the British Museum. Once John had signed the Magna Carta, the Barons reneged on their side of the bargain and invited Philip’s son, Louis the Dauphin of France (1187-1226) to take the throne.

The Dauphin invaded and the Portsmen fought valiantly at the side of Hubert de Burgh but he finally landed at Stonar near Sandwich. With his troops, the Dauphin marched to London and on the way, Canterbury and Rochester Castles surrendered to him. On reaching the Capital, the Dauphin was triumphantly welcomed. Meanwhile, at the Castle, with a garrison of 140 men, Hubert de Burgh along with the Portsmen remained loyal to the King. They knew that once the Castle fell then John would be forced to abdicate and the Dauphin could be crowned and as far as the Portsmen were concerned, their privileges and liberties would be lost.

De Burgh and his men held under siege in the Castle for over a year by the Dauphin and his men camped outside on the eastern foothills. Almost starving, de Burgh and his men still held out even when they heard that John had died. During this time, the Dauphin’s men tried to undermine the North Gate in order to gain entry, but failed. Then a massive contingent of re-enforcements set sail from France to invade. Secretly leaving the Castle in the hands of his deputy, de Burgh joined the Portsmen and set sail with the Cinque Ports Fleet to take the armada on. At the Battle of Dover on 24 August 1217 the Cinque Ports Fleet, under the command of Hubert de Burgh, routed the French Navy and prevented the invasion of England!

Continues on: Origins of the Cinque Ports and Dover Part II

- Presented: 06 February 2016