The Dynasty of Dover started with William Stokes, Margery, his daughter of married Edward Wivell and together they had bought Maison Dieu farmland that stretched from Maison Dieu House to Stembrook. There they had built the finest mansion in Dover. Of all their children, only two survived to adulthood, Elizabeth and Margaret. Elizabeth was christened at St Mary’s Church on 24 Oct 1685 and at the same church, on 12 February 1707, she married James Gunman. He was possibly the brother of Catherine Gunman who had married Francis Wivell, a relative of Elizabeth’s, in 1692.

James, possibly of Swedish stock, was a Royal Naval Captain and early in his career surveyed the Varne Bank. As the first to do so, it was named ‘Gunman’s shoal’. The Varne is a sandbank more than 6 miles long in the Dover Strait, at mid-point, some 7 miles due south of Dover Harbour. It was later surveyed on the order John MacBride (1735-1800), Rear Admiral of the Blue and Commander in Chief in the Downs etc., when it was renamed the Varne Bank. Due to its shallow depth, it was a favourite place for Dover’s fishermen, especially for cod and scallops. These days, as the Varne is in the Channel international traffic shipping lanes and a cause of concern to shipping and the Coastguard. There is a Trinity House automatic light vessel on the Varne and there have been calls to destroy it by dredging.

Elizabeth and James, along with their large family, lived in Wivell mansion fronting Biggin Street. Following Edward’s death in 1716, they gave the house a makeover in the Queen Anne style and the garden laid out in the ‘Capability Brown’ fashion of the time. When they finished, the estate was renamed Gunman’s Mansion and the house was said to be the grandest in East Kent. There does not appear to be any drawings or paintings of the house but there is a drawing of the nearby Yorke family home – after which York Street was named – a terrace of three houses that were dwarfed by Gunman’s mansion.

Of the land-holdings that Elizabeth brought to the marriage, they had Buckland Manor, at the bottom of Crabble Hill, rebuilt as their summer residence. The house was demolished at the end of the 19th century to make way for the tram shed, now a garage showroom.

On his marriage, James, like his father-in-law Edward Wivell, became a Freeman of Dover through the right of his wife. In 1737, he was elected Mayor and was particularly interested in harbour developments. The Eastward Drift that deposited shingle along the margins of Dover’s Bay continued to block the harbour mouth particularly at neap tides. This, it was envisaged, would be dealt with by the creation of the Bason in 1718 – later developed into the Granville Dock. The theory was that water collected in the Bason would be released, through dock gates at low tide, and the force would clear the shingle away.

It was not very successful so ships continued to anchored in the bay and boatmen conveyed passengers and luggage to and from the shore. The boatmen, although licenced by Dover Corporation, were not very honest and would row passengers part way between the ship and the shore. They would then threaten to throw the luggage overboard if the passenger did not give them more money. The boatmen were not averse to carrying out their threats and the authorities in Dover refused to do anything about the problem. This gave rise to the term Dover shark.

At the time, Admiral Aymer was one of Dover’s two Members of Parliament. As Captain Aymer, he was first elected in 1698 and since that time had remained one of Dover’s MPs having attained the rank of Admiral. In 1714, Aymer was appointed Commander-in-Chief Ranger of Greenwich Park and Governor of Greenwich Hospital. The latter had been established by Royal Charter in 1694 as a home for retired seamen of the Royal Navy. Aymer was a close colleague and friend of James and following his retirement from the Royal Navy, James was appointed the Treasurer of Greenwich Hospital. Further, Greenwich Park was part of East Greenwich and when James I (1603-1625) gave the Charter to the Commissioners of Dover Harbour in 1606, he granted the Commission, the Manor of East Greenwich!

On hearing James concerns over the harbour, Admiral Lord Aylmer invited Captain John Perry to look at the problems. Perry was an expert in sea and river defences and in his report, stated that although the harbour entrance was subject to being blocked, this had not occurred as often as it was generally believed. What was really happening was that ships captains were being deterred from using the harbour for fear that the entrance might become blocked, once they were inside. He suggested that the entrance be deepened and the South Pier be extended 150 -200 feet (approximately 46-61 metres) further out to sea. he went on to make other suggestions but when he filed his report, Lord Aylmer on was on his death bed – he died in 1720.

In 1723, Dover lost 66% of the Passing Tolls, revenue earned from ships traversing the Dover Strait. It was out of this money that harbour maintenance was paid and had been transferred to the Port of Rye. That port, in their petition, said that the Dover Harbour Commissioners had failed in constructing a shelter for shipping. The unofficial harbour master in Dover was James Hammond and his son, also called James organised the mud deposits in the harbour to be shovelled by hand onto carts and dumped out at sea. They also had gateway fitted into the Pent, now Wellington Dock, so that water, from the River Dover, collected there could be used together with the tidal water collected in the Bason, to clear the harbour entrance. Again, it was not very successful and the problem was exacerbated when the Castle Jetty was built in 1753.

Although these were major concerns of her husband, Elizabeth spent her time socialising in London and Bath. While enjoying the waters in Bath she died on 2 October 1739 age 55 years old. Her body was brought back to Dover and buried in the family tomb within St Mary’s church. At the time, James was a Commissioner of the Peace for the County of Kent and a Jurat – senior councillor – on Dover’s Corporation. Nonetheless, rumours began to spread that James was about to marry a woman much younger than himself. This reached the ear of Lord Hardwicke, Lord Chancellor of England. He was Philip Yorke, grandson of Simon Yorke, close friend of Elizabeth’s grandfather, William Stokes. Philip Yorke – Lord Hardwicke, was also the Recorder of Dover, whose role it was to assist the mayor on judicial matters and took a great deal of interest in the town.

Lord Hardwicke felt that it was his moral duty to write to James suggesting that if he was thinking of marriage, he should think again. James strenuously denied the rumour not only to Lord Harwicke but to others and led a virtuous life in Dover. However, when he died in London on 27 June 1756 aged 79, his young mistress, so it was said, was at his bedside. James was buried with his wife in St Mary’s churchyard and the tomb is engraved with the family arms: a spread eagle, argent, gorged with a ducal collar, or. Although worn it can be seen in the northern aisle of St Mary’s Church

Of James and Elizabeth’s many children, their eldest surviving son inherited Gunman’s mansion and many of their estates. Christopher, or Kit as he was popularly known, was christened on 27 September 1714 at St Mary’s church. His inherited wealth and social standing enabled him to make an advantageous marriage and shortly after, he purchased the lucrative position as Collector of Dover Customs.

Old Customs House built 1666 demolished March 1821 replaced by John Minet Fector Bank in 1821. Dover Museum

In those days, the Collector of Customs ran the customs shed collecting a percentage of all duties paid on exports and imports out of which he paid the staff. Only in small customs houses did the Collector actually work, Kit like many of his contemporaries just lived off the profits. The customs house, at that time, was on Custom House Quay that backed onto Strond Street and next door was Isaac Minet‘s residence. Kit’s maternal grandfather, Edward Wivell had made Isaac a Freeman of Dover in 1699. Since that time, the once Huguenot refugee, had developed his shipping business to one of the largest in the town. Isaac’s son William and his nephew, Peter Fector, helped him.

The Minet’s wealth, however, was not in the same league as Gunman’s – indeed, it was said that Essex Gunman, Kit’s wife, ‘might curl her hair in bank notes!’ The most powerful family in the town at that time, although not the wealthiest, was the Wellard’s. They were an ancient Dover family with a mansion at the top of Biggin Street, where the Prince Albert pub is today. It was the first domestic building to occupy the site following the Reformation (1529-1536) and the premises incorporated St Edmund’s Chapel. William and Alice Wellard owned the Cocke Inn and Brewery, on Strond Street, close to the Minet’s and the Custom House. The Wellard’s issued copper payment tokens instead of change that ensured customers returned.

In 1705 John Wellard, the grandson of Alice and William, was elected Town Clerk – the administrative authority of Dover Corporation. He held the post until 1718 when his son Robert succeeded him. he was a formidable administrator and was the Town Clerk until 1744 during which time he was also the Register of the Dover Harbour Commission – today the Chief Executive. In 1741, Robert was elected the Mayor of Dover by which time he had a country mansion in the Alkham Valley where he died in November 1744. His son, Alexander succeeded him to both administrative posts and also as Mayor in 1757. It would appear that Alexander sold the Biggin Street premises, having a mansion built on the corner of Bench Street and Chapel Land (then called Grubbins Lane). This he sold just prior to being elected Mayor, to the Churchwardens of St Mary’s whom, according to a plaque they erected in the church, ‘As a mark of their regard for their worthy Minister, Mr Birch, 1754.’

In 1751 Kit Gunman was elected Mayor and concern was being expressed by Peter Fector, one of the town’ Jurats, about the state of the harbour. Nouveau-riche, Peter was despised by the ruling elite and with the help of the town clerk, Robert Wellard, the town clerk both saw a way of getting rid of him. Peter was a naturalised Englishman born in Rotterdam. He was the nephew of Isaac Minet and by virtue of his family connections, Peter had purchased his Freedom in 1745. Kit was not the Mayor when Peter was asked to resign from the office of Jurat but as Robert Wellard made clear, Peter ‘… was not qualified to act as a justice on accounting to the laws of England being by birth a foreigner although he was naturalised.’

Alexander Wellard remained the Register of Dover Harbour Commissioners until 1765 when Jegan Wellard, who held the post until 1785, succeeded him. On 16 February 1762 Peter Fector’s daughter, Alice-Hughes, married Charles Wellard at St Mary’s Church. A stiff upper-lip was the order of the day. The situation at the harbour remained useless. Sam Latham, of the Latham banking family, was also the Harbour Commission treasurer and in 1769 brought in the highly esteemed civil engineer, John Smeaton (1724-1792). He suggested that the South Pier head should be extended by 60-feet and end in a point. Jegan Wellard responded by saying that the Commissioners coffers were insufficient to meet the cost. Joseph Nickalls (1725-1793), an engineer of some note was brought in and presented his report in 1783.

Nickalls stated that the harbour was not capable of accommodating warships as the water at the apron in the lower cross wall was only 10feet 6inches deep at neap tides. Moreover, the sill of the harbour gates was 18inches too high and the slope of the sides of the Great Pent (now the Wellington Dock) meant that only 47,160 tons could be held at neap tides. The result, he wrote, was that when the gates were opened the depth of water in the outer harbour was only 30 inches deep, and that such a force would not clear the shingle bar. Nickalls recommendations were estimated at £60,000 and to keep Sam Latham happy, the recommendations were put on hold. However, Nickalls did stay and undertook work to cleared the entrance, the worked – briefly.

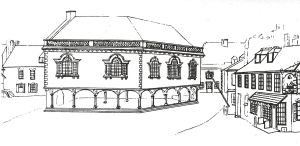

Dover’s Court and Town Hall from 1606 to 1834 situated in the Market Square. New windows were inserted in 1789. Dover Museum

Albeit, Kit Gunman ensured that the Wellard’s remained in the family circle of friends that possibly helped his election as Mayor in 1751 and again in 1760. By the time that Kit was elected Mayor in 1773 he had supplanted the Wellard’s influence but in July 1781, he died. Essex, his wife, died seven years later. The Gunman’s eldest son, James, was baptised 14 April 1747, and like his father was Dover’s Collector of Customs he also acquired property in Warwickshire. When James was old enough he actively participated in the complacency of council affairs. As expected of a member of Dover’s governing elite James was elected Mayor – in 1776, 1784 and again in 1789, that year the Town Hall was given a makeover and new windows were inserted.

James’ first year as mayor saw the beginning of the American War of Independence (1776-1783) and Captain Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821) was deployed in the town. A military engineer, Thomas was responsible for a number of important defence works at the Castle and in 1781, the Board of Ordnance bought two parcels of land on Western Heights. It was here that Page’s greatest work took place, for it was he who organised the building of fortified batteries that eventually became the major permanent fortress there. For this Page was knighted and straight away accepted into James Gunman’s narrow circle of friends. When peace returned Sir Thomas was responsible for the founding of the Dover Volunteer Association, the origin of the present Territorial Army. He married and built a mansion along the London Road, Buckland (now 110 London Road).

Sir Thomas was a close friend of John Latham, a local merchant and shipping owner who was concerned over the state of the harbour. Building on his influence within the town’s elite in 1784, Sir Thomas wrote an open letter saying, ‘The great advantage that might arise from Dover harbour to his majesty’s ships employed in these seas, in times of war, and the necessity, as the forces of our enemies increase, of using every possible means on our part to augment the navy of the country, cannot fail to interest every good subject in the success of all proper endeavours to improve a place capable of affording the greatest benefit to our marine; the practicability of which, and the means of drawing infinite advantage, both well known to every understanding.’ This did not exactly fall on deaf ears, but it was international events that were to make the difference.

Meanwhile, in 1777 another member of Dover’s close knit governing elite, Matthew Kennett instigated a chain of events that led to the Dover Local Government Act of that year. At the time, Dover was overcrowded; the streets unpaved, unlit, crooked and narrow while the sewage system consisted of a channel running down the centre of the streets to the river or harbour. As Mayor, Matthew Kennett headed the newly created the Dover Paving Commission that came out of the Act, the following year.

To be appointed one of the 40 Commissioners, the Freeman had to possess or be entitled to a personal estate to the value of £500. Alternatively, to receive annual rents to the value of £20. The Commissioners job was to watch, light, and pave the town with wooden blocks. To reintroduce scavengers to clear away the town’s rubbish and sewerage. They had the right to licence hackney coaches, chaises, fly’s etc, to appoint their stands and regulate their fares and also regulate the fares of boatmen, watermen and porters, and the general convenience of the town committed to their care. The Act also empowered the Commissioners to borrow £8,000, but to pay this back they levied 6d (2.5p) tax on every house and Coal Dues were introduced. The latter, at that time, was 1s (5p) duty on every chaldron (25½cwt or 1,295kg) of coal imported through Dover whether by sea or by road. The duty was paid at the towns toll gates that had been imposed by the Turnpike Acts that created cross-country roads.

All of this was too much for James to digest, so he took himself off to enjoy the delights of London and Bath and other similar social haunts. It was at one of these places that he met the wealthy 33 year-old Sarah Hussey Delaval of Northumberland, whom he married on 13 April 1805. Sarah’s father, Edward, had been a Member of Parliament but in those hallowed corridors he had collapsed and died in 1814, and was subsequently buried in Westminster Abbey. Both Sarah and her mother, also Sarah, on the death of Edward Delaval inherited part shares in a palatial estate at Doddington, Lincolnshire.

Following their marriage, James brought his young wife and her mother to Dover, where they settled in the family mansion. This was the era of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) and Dover was a hive of activity and social gatherings as the town was both a military base and naval base. Sarah Gunman became well known throughout Dover for her philanthropic work and particularly showed an interested in education the children of the town’s poor. In 1820, when Queen Street Charity School, the forerunner of St Mary’s school, opened its doors to educate to 200 boys and 200 girls, she made a substantial contribution to its funds. Sarah was also interested in the town’s history and persuaded James to help to pay for the publication of Rev John Lyon’s two volumes, ‘History of Dover’ (published in 1813). The books are dedicated to James Gunman.

Sarah was also well known for her social gatherings where she raised interest for her philanthropic work. The Gunman’s could count among their close circle of friends, all of the town’s established elite and the up and coming wealthy, such as members of the Fector, Latham and Rice banking families. At their soirees, were senior officers from the barracks and ships moored in the bay also attended, one particular officer, the handsome Lieutenant – Colonel George Ralph Payne Jarvis became a close friend of the family. However, on 29 June 1824 James Gunman died and less than a year later, on 4 May 1825, Sarah died of consumption (tubercolosis). A monument to Sarah can be seen in St Mary’s Church.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury 23 October 2008