At noon on Saturday 14 July 1883, a royal salute announced that the third son of Queen Victoria, HRH Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1850-1942) and his wife, Louise, had arrived by train at the Town Station in then Pier District of Dover. They had come to open the new part of the then Town Hall and a municipal park, both to be named after the Prince.

The Duke and Duchess, to the delight of the town, had agreed to open both and a splendid welcome was organised by the Mayor, Sir Richard Dickeson. Escorted by the cavalry from the barracks, the royal couple were preceded by a procession of sixteen carriages containing distinguished visitors and dignitaries. Before lunch, they opened Connaught Park and then the procession wended its way down Park Avenue, thronged with cheering crowds, along Park Street to the Maison Dieu – then Dover’s Town Hall

As the Duchess climbed the steps up to the Stone Hall, local women scattered fresh flowers in front of her. Inside, the town’s council, all wearing a marguerite in their buttonholes in honour of the Duchess, welcomed the Royal personages. Then the royal couple, along with 450 guests, enjoyed a grand luncheon, after which the Duke of Connaught declared the Connaught Hall open. It had been planned that they would spend the remainder of the afternoon in the grounds of Dover College but heavy rain put a stop to that. During the following week, the Mayor and Mayoress held a grand ball for about 1,500 guests in Connaught Hall.

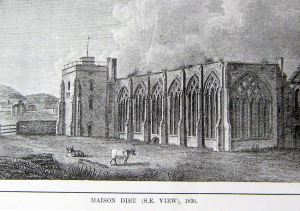

The history of the Maison Dieu can be traced back to Hubert de Burgh (c.1160– 1243) who was in the service of King Richard I until the King died in 1199. De Burgh was then appointed the Chamberlain to King John and Constable of Dover Castle in May 1202. The following year he found the Maison Dieu Hospital. The Great Chamber, or Stone Hall, dates back to 1253 and on the north side was the church, behind which, and running the length of Stone Hall, was the guesthouse. In 1524, Henry VIII ended all religious functions at the Maison Dieu and ten years later all the monks were evicted. The Maison Dieu and its lands became a navy-victualling depot in 1552 remaining so until 1815. The building then came under the control of the government’s Ordnance Department until 1830 when the Royal Engineers would move in as a temporary measure until Archcliffe Fort was ready.

Along with Maison Dieu House, next door, the buildings were put up for sale. William Fulke Grenville, of Marine Parade, bought them at a London Auction Market 20 May 1834 for £7,680. At the time the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 was expected to herald major changes in local government and the council saw this as a good time to move from 17th century Guildhall in the Market Square. However, the council could not afford the asking price so the Ordnance Department agreed to sell Maison Dieu House to a private party, William Kingsford – who owned Buckland corn mill – and offered the Maison Dieu to the council for £7,000. Unfortunately, the council was still £1,500 short of the new asking price so they used, as collateral, the town’s silver. This had been given by Peter Fector in 1814 and was pawned to the Fector Bank so that the deal could be made!

On the site of the ancient guesthouse, a new four-storey gaol was erected and was used as such for the next thirty-two years until prison reforms dictated a new prison. The old gaol next to the Maison Dieu was demolished in 1877 and a year later, the Prison Act made the new prison obsolete. During that time when finance was available, alterations and additions were made to meet the changing needs of the council.

About 1850, Ambrose Poynter (1796–1886), whose father had landholdings at West Cliffe, was instructed to draw plans for restoration of the Town Hall and during the years 1852-1862 his designs were carried out, chiefly under the direction of his successor, William Burges (1827-1881). Although, the council were more than satisfied with the results, towards the end of the 19th century towns were increasingly being judged by the munificence of their town halls. Dover, at that time, was on the ascendancy – by the turn of the century it was one of the top ten wealthiest towns in the country!

A grand town hall, where public meetings, entertainment’s and the ‘promotion of philanthropic objects’, was needed. This did not go without opposition, mainly on the grounds of cost that was exacerbated when it was suggested that the new hall would be built on the site of the old prison. The government actually owned that site and it cost the Corporation £3,039 to buy the land. William Burges was called upon to design the new hall but, by that time, was recognised as the leader of the Victorian Gothic revival and as such his fee had increased! In 1881, the year Burges died so his partners Richard Popplewell Pullan (1825-1888) and John Starling Chapple (d1922) completed the development. The council borrowed £17,500 from the Hearts of Oak Society at 4% per annum to pay for the building.

1991 Plan showing the location of Connaught Hall. On the plan the room shown as Maison Dieu is now called the Stone Hall

The builder was a local, Herbert Stiff who cleverly incorporated the wall shared with the ancient Stone Hall which contained seven arches, six pointed and one wide semi-circular, resting on what had once been eight pillars. They were a legacy from the original 13th century building and can still be seen. When completed it was said that the Hall was one of the finest public buildings in the county of Kent. Not including the stage, it measures 20.31metres by 16.31metres and the final cost, including adjoining rooms one of which was the Mayor’s Parlour, was £19,000.

At the same time as Connaught Hall was built the tower, holding an illuminated clock, was erected on the outside. The clock was supplied by E Dent & Co. of London and John Bacon’s name is on part of the gear train. Although the clock is no longer illuminated and does not always tell the right time, it remains a much-loved feature of the town. Inside the building are other clocks, including one under the balcony in Connaught Hall. This was presented by the sisters of William Woodruff in 1890 who ran a jeweller’s business in Snargate Street and from 1865, New Bridge.

The stage proscenium was designed and built by Flashman’s of Dover in 1893. The magnificent organ was erected as a gift of Dr Edward Ferrand Astley (1812-1907) and was officially handed over on Wednesday, 5 November 1902. The organ cost over £3,000, was fitted with electronic action throughout and was nationally applauded, at the time, as being ‘a veritable triumph in organ building.’ The Borough Organist, Professor Harry J. Taylor was in charge of the instrument until he died in 1936. Recently, there has been talk of restoring the organ, but this is likely to be in the region of £¼m plus £2,000 a year to maintain.

In 1899 Gugliemo Marconi (1874– 1937) exhibited his radio equipment in Connaught Hall. Marconi had previously conducted radio experiments, assisted by the Royal Engineers at Fort Burgoyne, near the Castle, at Swingate and St Margaret’s Bay. On Christmas Eve 1898, Marconi demonstrated his new wireless system by transmitting a signal from the South Foreland Lighthouse, St Margaret’s, to the South Goodwin Lightship, the world’s first shore to ship radio transmission. On 27 March 1899 he transmitted the first international wireless message, ‘Greetings from France to England,’ from Wimereux, near Boulogne to the South Foreland Lighthouse.

Connaught Hall quickly proved popular with the townsfolk for besides being used for full Council meetings – the Council Chamber was used at other times. The Hall was, and still is, a popular venue for dinners, dances, musical productions and civic meetings. However, following the installation of the organ, theatrical productions were banned. However, in 1894, 1,300 people packed into the Hall to hear a talk on the New Hebrides. This was far from the first time that the Hall was so packed but the local fire chief – Police Superintendent Thomas Osborn Sanders – raised concerns following which numbers were restricted.

In 1923, an application was granted to use the Connaught Hall as a cinema and it was estimated that there was room for 538 seats on the ground floor, 46 in the gallery and 72 in the side balconies. At the same time the council relented over theatrical productions. Two years later work began on the restoration of the whole of the Town Hall, carried out under the supervision of the government’s Office of Works officials but was later severely criticised. At the time they also had control of the restoration and maintenance works at Dover Castle. During the restoration, the ancient stonework between Connaught Hall and the Stone Hall was found to be badly corroded and the local firm, Hayward and Paramor carried out the repair work.

With the threat of World War II in 1939 all the stained glass windows were removed from the Maison Dieu and the cellars were turned into emergency headquarters. The building was not directly hit during the war but it did suffered damage from nearby explosions. The Museum in Market Square, however, took direct hits and what was salvaged was moved into the cellars below Connaught Hall. The Museum stayed there until the Market Hall was re-built and in 1989 when it was returned to its old home. Above the door, on the Ladywell side of the Maison Dieu, carved into the stonework, is the word ‘Museum’ above the door what was the entrance. The door came from the old St James’ Church.

Following the D-Day landings in June 1944 the bombardment of Dover increased until the last shell fell on the town on 26 September. On 18 October George VI and Queen Elizabeth came to meet the folk. They also inspected Civil Defence workers in the then Town Hall and this is recorded on a plaque in the Stone Hall. The reception was held in Connaught Hall.

The whole building was taken over by the newly formed Dover District Council (DDC) in 1974 who used it for council meetings until moving to new purpose built headquarters at Whitfield, Dover. From then on, the Charter Trustees, a ceremonial body made up of elected DDC councillors representing Dover’s wards, were allowed, by DDC, to use the buildings. The Dover Town Council (a parish council) succeeded the Charter Trustees, in 1996, and DDC obliged them to find an alternative venue. The Maison Dieu was then, and still is, leased to a private company.

To Visit Dover’s Maison Dieu, including Connaught Hall:

Guided tours are provided by volunteers from The Dover Society and are available on Wednesdays every week from 10am and 4pm (from 1 November to 31 March 10am to 2pm) and last up to an hour. For further information and group bookings, please telephone (UK): code: 01304 then 205108, 206458 or 823926. Outside the UK the code: 44 0304 plus the number.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 02 July 2008