Dover’s harbour, up until the late medieval period, was at the east end of the harbour under Castle cliff, approximately where the Swimming pool and Sports centre are today. Due to a series of natural catastrophes, this harbour became useless and was moved to the west side of the Bay where it developed over the next few centuries. These developments affected the tidal streams causing what became known as the Eastward or Longshore Drift, which caused shingle to be deposited around the edge of the Bay. However, for a variety of reasons it was necessary to access the Castle from the sea so in 1753, a wooden pier was built – the Castle Jetty – where ships could tie up and cargo unloaded for the Castle.

Smith’s Folly, East Cliff, from an original drawing by Rawle and engraved by John Nixon 1801. Dover Library

This triggered the Law of Unintended Consequences as shingle built up against the new Jetty and soon a broad strip of beach accumulated. On the newly created land Guilford Battery was built, fishermen erected huts and Captain John Smith built his Folly. A painting dated 1816 shows that a windmill stood where Athol Terrace was eventually built and four years later, records tell us that a terrace of cottages had been erected. A Scottish lady, Mrs MacIntyre, apparently purchased number 3 and suggested the terrace to be called Athol Terrace after Blair Athol, to remind her of her native land.

The soft white chalk of the steep cliffs was hewed out to create homes that were captured by artist John Nattes (c1765-1822) in a series of sketches. These caves were described as being dry, comfortable, and cool in summer and warm in winter and the 1841 census shows that James Hart lived in one and Widow Mary Burville, along with her four children lived, in another. The Burvilles (various spellings) were said to originate from Tilmanstone, east of Dover, and Mary’s husband, Benjamin, was a carrier of coals. He was killed when he fell from his cart at Broadlees Bottom in 1833 and a public appeal for financial help was launched by the Dover Telegraph. Another artist, W Henry Prior, between 1833 and 1857 used water-colours for his paintings of the interiors and exteriors of the caves and one may well have been Mary’s. One exterior painting shows a cave with three windows and a chimney coming out of the cliff face several feet above the entrance door.

Captain John Smith owned much of the newly created land for his son, Sir Sidney Smith, sold it to Wilson Gates a builder. He was responsible for the development of East Cliff and the adjacent Athol Terrace that we see today. This took place between 1817 and 1840 the date of 1834 can still be seen on one set of the mansions. The new residences proved popular and soldier Francis Cockburn (1780-1867) later General Sir Francis and his wife Alicia (1782-1854) moved in and they stayed until their deaths. Sir Francis played a major role in the European settlement of Canada, was the Commandant of the Settlement of British Honduras (now Belize) and became the Governor of the Bahamas, for which he was knighted and a major role in freeing US slaves. Here in Dover, he was applauded over his compassion for widows and orphans of drowned seamen.

Once the area had been developed, which parish did it belong to became a concern of Dover council especially as the residents were not paying any rates! This came up before the courts at the East Kent Quarter Sessions on 9 April 1847. After the hearing, where twenty witnesses had given evidence, it was decreed that the houses were in the parish of Guston, and were thereafter so rated. However, for municipal purposes, for instance, Parliamentary elections, East Cliff and Athol Terrace were in the Borough of Dover!

Dover Corporation were annoyed, for at the time the town was having flooding problems at high tides for which they were having to pay for sea defences. They decided that as East Cliff and Athol Terrace did not to contribute to the rates, the defences stopped at the Boundary Groyne – so called following the court Ruling. However, at the time of the Ruling work was starting on the Admiralty Pier, at the west end of the Bay. This directly affected the Eastward Drift causing the denuding of the seashore at the eastern end of the Bay and serious flooding at East Cliff. This was noted in the Rawlinson Report on Public Health in Dover published in 1849 but nothing was done.

As the situation deteriorated, pressure was put on Dover Corporation who submitted a Private Bill to parliament seeking approval to carry out what was becoming essential sea defence works. The Dover Ratepayers Association, however, strenuously opposed the Bill, to the extent that in the local elections of 1876, they put up candidates in all the Wards. Although only one candidate was successful this was sufficient to raise doubt over the use of the Borough funds for the promotion of the proposed legislation. The Mayor, George Fielding, chaired a public meeting, which was boisterous but ended with a division in favour of the Bill – but only just.

The Ratepayers Association demanded a poll of all Dover ratepayers but on 1st January 1877, before the referendum, a vicious westerly storm swept into the bay damaging much of the partially built Admiralty Pier. Masonry was carried across the Bay impacting on the residences of East Cliff and at the same time, the raging seas flooded the whole area. The result of the poll was 2246 votes for and 281 against the Sea Defence Bill, which became an Act in 1877 and the contract for £9,428 was given to Josiah Paul of Queenborough. The money was borrowed, with the consent of the Local Government Board, on the understanding that the East Cliff / Athol Terrace properties would be rated for the purpose until the debt was repaid.

At that time, and for most of the 19th century, senior army personnel occupied the large mansions and fishermen the cottages on East Cliff back road. In 1846 the Finnis Family, local timber merchants and philanthropists, opened the British and Foreign School in one of the mansions. The school had no religious barriers and accommodated 50 girls and an unspecified number of boys who were charged 2d a week to attend. Some of the villas along the back road and in Athol Terrace offered lodging accommodation although some were bought as summer residences.

Typically, Lady Clifford, who bought 4 Athol Terrace, would arrange local staff to get her cottage ready before she arrive with her butler and maid for the summer. Charles Okey and his family followed the same format until he was appointed to the Antigua Legislative Council. One of those who lodged at 1 Sydney Place was Marian Evans, better known as novelist George Eliot (1819-1880). She stayed in 1855 and wrote, on 16 March, to her friend, Sarah Sophia Hennel who lived in Coventry. The novelist said that ‘Dover looks very lovely under a blue sky. The cliffs with the soft outline of hills beyond looking, as Kingsley says, like the soft limbs of mother Hertha lying down to rest, and the town with its blue smoke made a charming picture under the afternoon sun as I walked up the castle hill. But here as everywhere else man is vile cheating one of sixpences and making one feel misanthropic in spite of oneself. My lodgings however are very comfortable and I have a nice quiet woman to wait on me.’

The dwellings under the shadow of the cliffs were/are vulnerable to cliff falls. During the night of 14 December 1810, a fall killed Eliza Poole and her five children while they were sleeping. John Poole was pulled out of the debris and the only other survivor was the family pig. On 17 November 1872 two houses were demolished by a fall of cliff and less than nine days later on 25 November another cliff fall causing several houses to be devastated. A gale on 16 September 1935 brought about a cliff fall damaging 8 Athol Terrace. Following a fall in October 1967 the cliff was trimmed to prevent a reoccurrence. However, in February 1980 a six-foot high chalk boulder, weighing over five-tons, landed in one of the back gardens. Since then, strong netting has been put over the cliff face in order to minimise the impact of falls.

In order to provide work for the unemployed and for the benefit of visitors the North Fall (Meadow) Tunnel Footpath was created by the Dover Chamber of Commerce in 1870. Supervised by John Hanvey, Borough Surveyor, it was designed to provide a short cut from the beach to the Castle and for the most part was in a tunnel. A man was employed at 2s6d (12.5p) a week to sweep the path and to stop local boys frightening people by yelling down the tunnel. It was probably some of these boys that discovered the hitherto unknown caves behind Athol Terrace in 1891. A pathway was laid, at about this time, to the top of the cliffs giving fine views across the Bay and the Channel, as well as a bracing walk to St Margaret’s Bay. This walk became a favourite with tourists and Buckland shopkeeper, George Small, seeing the potential, converted an Athol Terrace cottage into a cafe, and opened up one of the caves behind.

As the 19th century progressed the town boundary changed, putting more of the properties in the Dover Borough. A shop opened at 62 East Cliff providing groceries, a post office and bread made on the premises. A number of the large villas were adapted into convalescent and nursing homes for soldiers injured in action. These increased during the Boer Wars (1899–1902) with the largest, the Grosvenor Convalescent Home for Sick Soldiers, opening at 18 East Cliff in June 1899 – four months before the Wars officially started. Of note the house was later sold to dentist W. Hodgins Saul, whose son, Patrick Saul, the famous Sound Archivist, was born there on 15 October 1913.

With the construction of the Admiralty Harbour, from 1898, the cliffs at the east end of the Bay were cut back destroying the North Fall (Meadow) Tunnel Footpath and the caves at the eastern end of Athol Terrace. Pearson’s, who won the contract to build the new harbour, used compulsory purchase powers to buy the front gardens of the Athol Terrace cottages, paying each householder about £60. The remainder of Athol Terrace frontage to the sea was lost as the construction of what became Eastern Dockyard took place.

During World War I properties at East Cliff were commandeered by the Admiralty, 23 East Cliff became His Majesties Naval Depot and 24-27 East Cliff the Headquarters of the 6th Flotilla (Dover Patrol). During that War, the mansions came in for a battering from German Vessels with 14 East Cliff suffering notable shell damage on the night of 15-16 February 1918.

Following the War the Dover garrison was run down and this had a direct effect on the occupation of the mansions front East Cliff. Exacerbating this was the threat of the demolition of the properties along the East Cliff back road and Athol Terrace when, in 1920, the Channel Steel Company applied to run a railway line following the base of the cliff to St Margaret‘s Bay. This came to nothing but the whole of the area was blighted for some years after. In 1934, the boundaries were yet again changed and the remaining properties came under Dover Corporation. That year, in order to relieve the high unemployment in the area, the East Cliff path we know today was reconstructed.

As international tensions started to rise in 1937, the caves were requisitioned by the Council to provide air raid shelters, but when the situation appeared to cool, they were handed back. In February 1939, the council, against government advice, re-requisitioned the caves between Trevanion Street and Athol Terrace to provide deep shelter accommodation for approximately 23,550 persons. The complex of caves is connected by a series of tunnels and these days are in the care of English Heritage as part of its Dover Castle property.

1940 South Staffordshire Regiment marching along East cliff, note barbed wire along the seashore. David Collyer

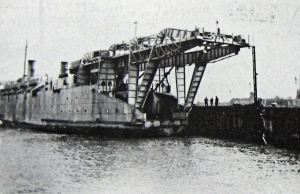

During World War II (1939-1945), the caves were well used, as the town came under heavy bombardment and the properties in the area suffered. Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, Elsan toilets were introduced in the caves. At Christmas 1941, a party was held for over forty children attended by a naval officer, dressed as Father Christmas, who gave out presents. Following the D-Day Landings, in June 1944, Dover became a major port of embarkation for reinforcements of men, munitions and machinery. Tanks of various types, landing craft, and amphibious vehicles for crossing the Rhine and the floods of Holland, were sent from the Port. Embarkation jetties and ramps had already been built in 1943-44 on the East Cliff beach and at the Eastern dockyard to this end.

In the last years of the War Dover Corporation produced a post-war plan that included the demolition of East Cliff and Athol Terrace in order to build an access road to the Eastern Dockyard. This was ear marked as an industrial zone. The plan was endorsed by Sir Patrick Abercrombie, Professor of Town Planning, and covered much of the town. In November 1947, the Plan was given consent by the Government and demolition began in 1948 but there was a change of mind before East Cliff was reached. That summer Messrs Burwill of 6 Athol Terrace, Taylor of 31 and Cockings of 44 East Cliff, all manned 12 seater pleasure boats around the harbour for tourists returning to the town. To meet the needs of these tourists it was decided to extend the promenade to the Eastern Dockyard and build a lavatory block opposite East Cliff.

In 1952, the cost of repairs for the Castle Jetty became a major issue – two years before repairs had cost the council £4,295. A joint bill of £1500 was sent to the residents and at the same time, the owners of the properties facing the sea front were told that they were to lose part of their gardens to enable the widening of the road. It appeared that it was expected that these combined actions would convince the residents to move out so that the houses could be demolished without the council having to pay compensation. Instead the residents reacted by staying put, protesting loudly and raising petitions. In July the Ministry of Housing and Local Government held an inquiry at the then Town Hall (now the Maison Dieu) who upheld the council’s view that the properties should be demolished.

Opening of the Eastern Docks 30.06.1953 by the Minister of Transport the Rt. Hon. Alan T Lennox-Boyd MP. Accompanied by the Chairman of DHB – H T Hawksfield and the General Manager – Cecil Byford. DHB – Lambert Weston

On the 30 June 1953, the new Eastern Docks opened and traffic proved heavy, noisy and polluting. Not long after the Corporation promoted Bill in Parliament regarding Dover’s bus services and used the opportunity to secure a repeal of the 1887 Dover Corporation (Sea Defences) Act. In 1956, the council were informed that they were successful and at the same time the War Department conveyed to them their interest in a small part of the foreshore and promenade at East Cliff that including Castle Jetty. Earlier that year, it was proposed to make Townwall Street, Douro Place and parts of Marine Parade and East Cliff a trunk road.

The first section of the dual carriageway was opened in April 1959 and included the demolition of one of the East Cliff villas. There was also the loss of more of the front gardens. Two years later, as the Port of Dover was rapidly becoming the busiest passenger port in the World, the road was further widened at a cost over £22,500. Many of the residences, by this time, were offering bed and breakfast accommodation for Continental travellers and permission was given to turn one of the mansions into a youth hostel.

Not only was Dover the busiest passenger port in the World, during the 1960s it was becoming one of the busiest freight ports and the demand for more road space increased. In December 1968, Mears began an 18-month contract to build a new terminal designed to speed the flow of passengers and to provide space for the expanding lorry borne freight traffic. Costing about £1,5m it was completed in 1970 and opened on 1 May by Fred Mulley, Transport Minister. That summer saw a massive increase of traffic through the port, particularly lorries and in July, during a national docks dispute that did not include Dover, the town was brought to a halt. The pressure was on to demolish the East Cliff /Athol Terrace properties.

That year, Kent County Council, under new legislation, became responsible for earmarking Conservation Areas and East Cliff and Athol Terrace were included. Both the council and Dover Harbour Board fought bitterly against the proposal. Over the next few years, a number of these residences were turned into flats and bed-sits, ironically mainly used by those with jobs associated with Eastern Docks. A fire, in September 1979, led to questions being raised over fire safety and escapes.

In 1992, following a local reversal of policy, Dover District Council named the area as having special interest. Nonetheless, the Eastern Docks continued to expand and the road was widened at the expense of the seafront. In 2009, the Dock Exit Road opened that effectively cutting East Cliff and Athol Terrace from the sea.

The East Cliff / Athol Terrace area has all the makings of a tourist jewel most towns would be proud to promote. It has lovely rows of houses that are packed with history and captivating stories, some of national importance. The footpath leading up and along the cliffs to St Margaret’s has been named a one of the National Trust’s top 10 hiking routes in Great Britain (2013). Yet, time has shown that these attributes are ignored by the planners.

- Presented:

- 28 September 2013