When Dover Castle was built in the reign of Henry II (1154-1189), included was a prison and this was situated near the Canon’s Gate at the main entrance. Initially, it was a general-purpose prison, then a political and ecclesiastical prison and later a debtors’ prison. At that time a collection box was mounted outside the Castle Gate and during parliamentary elections candidates made a particular point, with attendant publicity, to put money in the box. Once the elections were over only the winners continued the practice until the next parliamentary election. In the eighteenth century prison reformer, James Neild (1744-1814), made a bequest of £800 for the prisoners welfare in the Castle prison and when it closed in 1855 the bequest was passed on to Dover Almshouses.

Maison Dieu prior to the demolition of the Prison, which looks like a tower on the left but was the full length of the Maison Dieu. LS

The town of Dover had prisons from the earliest times and during medieval times, up until 1746, there were prisons for different classes of inmates in the town wall gate-towers. That year, Dover Corporation bought a house near Queen Street to provide a purposely-designed town gaol – as the British call such institutions. The lane on which it was established was renamed Gaol Lane and still exists. The gaol was partially re-built in 1795 then later in 1820 a mob attacked it to let the inmates free. The building was damaged beyond repair and another, much larger, prison was built on the same site. In 1836 the council bought the Maison Dieu and attached, on the Ladywell side, they built a relatively massive prison.

As Britain colonised different parts of the world, transportation became the choice punishment for British convicted prisoners and early in the 19th century, Australia was the most favoured. That is, with the exception of South Australia, which was never used as a penal colony. In the 1840s, due to pressure from the New South Wales’s authorities, criminals ceased to be sent there but transportation to Western Australia and Tasmania stayed on the statute book for another ten years. By that time, it was noticed that after completing their sentence many stayed in the new country and it was evident that transportation was being seen as a free passage to build a new life! The Penal Servitude Act of 1857 abolished sentences of transportation but still allowed those sentenced to penal servitude to be taken overseas to serve part of their sentences. Ten years later this loophole was finally closed.

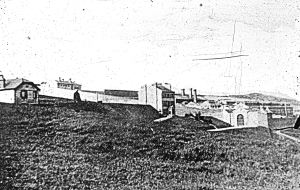

Eastern Heights – Langdon Cliff, Langdon Hole and South Foreland from the end of Eastern Arm – LS 2013

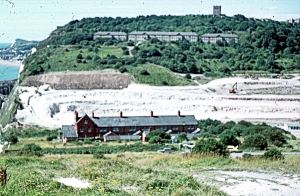

National reforms made the Ladywell prison obsolete and a new prison was created under Maison Dieu’s, Stone Hall. To do this, the floor of the Stone Hall was raised and the steep flight of steps we have to climb for access, were built. The new prison opened in 1867 but when Borough Prison Jurisdiction was abolished under the Prison Act 1877, except for the cells used for police purposes, the prison was demolished. In 1940, police cells in Ladywell Police Station replaced those police cells but the door can still be seen opposite Biggin Hall. The police cells at the police station were closed in 2011. Following the closure of the barracks on Western Heights, in 1954 the Citadel was turned into a prison. Four years later it became a Borstal Institution and was later renamed a Young Offenders Institute. Just after the millennium, the buildings were refurbished as a detention centre for asylum seekers. Back in the latter part of the nineteenth century Dover had another prison at the Langdon Cliff beauty spot on the Eastern Heights and two small buildings still stand.

The Prison Act of 1877 aimed at coordinating the prisons and practices within prisons. The Home Secretary at the time, Conservative Sir Richard Cross (1823-1914), was given the power to centralise British prisons and this was delegated to the Board of Prison Commissioners with the support of an inspectorate. Prison reformers, such as James Neild, had been canvassing for a change in dealing with convicted prisoners for over a century. They wanted prisons to change from pure punishment to include reforming of the prisoner in order that when they were released, the prisoners could then become worthy members of society. This, it was felt, was best achieved by cutting the length of sentences and implementing continuous and methodical employment of criminals in useful labour. These reforms were to be implemented under the authority of the Convict Labour Commission.

The following five years saw a general fall in the number of prison inmates while the general population increased. Although this could be attributed to the implementation of reduced sentencing the Convict Labour Commission announced that it was the reforms they had introduced and looked at making further prison reforms. One of these was the building of new prisons designed to meet the changes in the general philosophy of prison reform. Considerations taken into account was to be the locality stating that the new prisons were to be built and of a type where there was no risk to either the public or the management of the prisoners. The prisons were to be able to provide continual employment to the inmates for a number of years and the work itself was to be of a national utility that would not pay if undertaken in any other way. Finally, two sorts of work were considered ideal, the construction of harbours of refuge and the reclamation of land.

Dover had been fighting for a Harbour of Refuge from the eighteenth century and in 1848 construction of the western arm – the Admiralty Pier – was started. Subjected to delays for financial and political reasons, the Pier was not completed until 1871 and both the Dover Harbour Board and Dover Corporation were in despair as to whether the eastern arm would ever be built. Nonetheless, the town kept up the pressure and in 1875, the Government introduced a Bill for the formation of a Harbour of Refuge at Dover! This stated that the new harbour would enclose 300 acres of the Bay at a cost of £970,000. Having quickly passed through preliminary stages, the Bill was referred to a Select Committee. The delegation, on behalf of Dover was led by the Commander-in-Chief HRH Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge (1819-1904) and supported by Naval surveyor Major-General Thomas Collinson (1821-1902), Civil Engineer Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891), Dover Harbour Board’s Register James Stilwell (1829-1898), Hydrographer of the Admiralty Captain Evans, the Board of Trade resident engineer at Dover Edward Druce (d 1898) and others.

In June 1875 the Committee reported to the House of Commons that the formation of a large harbour at Dover, from a naval and military point of view, was of great importance, particularly as there wasn’t a coaling place between Portsmouth and Sheerness for refuelling ships. Further, there was no proper place for embarking troops onto ships from the major barracks at Woolwich, Chatham, Sheerness or Portsmouth. However, on the 25 June that year, the Government withdrew the Bill on the grounds of lack of finance. Frustrated, in July 1882 the Dover Harbour Board decided to try and raise the money to build the proposed harbour themselves. They applied to Parliament asking for the powers necessary to create a Harbour of Refuge together with a Commercial Harbour that would enclosed Dover bay as far as the Northfall Tunnel – Eastern Cliffs. The proposal was given Royal Assent but before work commenced, the Government intervened with a proposal of its own.

The Prison Commission’s Report had been published in January 1883 and the proposed Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour at Dover, fitted in with the recommendations. Thus, the Government would partially fund the proposal as long as convict labour was used. The Prison Commission was so excited about the proposal, even before it had been officially sanctioned, they had produced a work plan! This gave the size of the convict groups that were ideal for undertaking such work and how other problems would be dealt with. Their conclusion was that the groups would be small, kept separate and work under the watchful eyes of two or more warders. However, it would appear that the Commission had not taken into account the rise and fall of the tides, particularly the extent of the strength during spring tides and that they were cyclical, that is, two weeks after the strong spring tide there would be the weaker neap tide. Further, that the times of high tide change on a daily basis and that the strength of the wind has a direct effect on working conditions. Finally, satisfied that both problems of tides and weather were insurmountable they agreed that they had to be accommodated within the regime of running an efficient prison. Nonetheless, there was the concern over what would happen to the convicts once the harbour was finished and therefore, to justify building a prison, to build a Harbour of Refuge at Dover, this project was to take at least 20-25years.

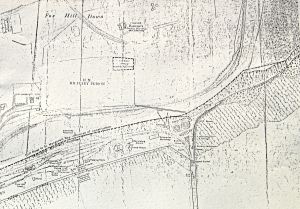

The Commission asked the Board of Trade resident engineer at Dover, Edward Druce to find a suitable site and he suggested Fox Hill Down, to the east of the Castle. It was owned by the Ecclesiastical Commission and was accessed from the Seafront, at that time, by the Northfall Tunnel. The major drawback was the lack of suitable building material in the vicinity but the Commission suggested that this could be brought in barges from Rye using convict labour. On 16 January 1883 came the news that Major-General Sir Andrew Clark (1824-1902), Inspector General of Fortifications (1882-1886) had been told by the Home Office that the Government had decided to construct a National Harbour at Dover. Further, the work was to be undertaken by convict labour. The Dover Express of 19 January stated that the prison buildings would be permanent and once the new Harbour of Refuge was built, they would become barracks for the Castle garrison.

Although the new prison was going ahead, parliament had not sanctioned the Dover Convict Prison Bill. To rectify this the Home Secretary, Sir William Harcourt (1827-1904), presented the Bill to the House of Commons on 23 February 1883. He stated that the harbour project would take 12 years to complete and approximately 900 convicts would be used. The scheme, he said, would cost £790,000 but a larger scheme costing £1,040,000 would be more cost effective in the long run as it would provide a suitable Admiralty harbour and provide work for the convicts for a longer period. He finished by saying that for the duration of the project, the convicts would be transferred to the Admiralty and on completion of the Harbour of Refuge, would be transferred back to the Prison service. As the Bill progressed through parliament, Sir William emphasised the need for a new project as the work for convicts at Chatham and Portsmouth was coming to an end. He showed little interest in the Dover Harbour of Refuge aspect of the proposal other than lengthening the proposed time it would take to build.

Taking into account Harcourt’s recommendations, a Parliamentary Committee, in April 1883, sanctioned the Harbour of Refuge proposal to be built at Dover employing convict labour. That the new harbour should be 520 acres and that it was to take about 25 years to build. In August that year, parliament approved that £16,000 could be spent on the proposed prison and 20 acres of cliff-top land was to be purchased from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. In Dover, the desperate need for a Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour engendered a general feeling of disappointment due to the length of time it was going to take to build. Nationally, this was seen by many commentators that Dover was against the use of convict labour per se. Although this was vehemently denied by Dover Harbour Board and Dover Corporation, the Prime Minister (1880-1885) William Gladstone (1809-1898) reacted by saying he was putting the proposal on hold until an expenditure survey had been made.

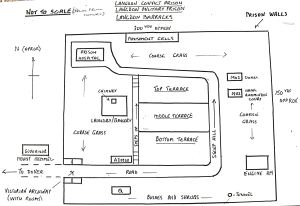

Nonetheless, the land for the prison was bought and the contract for building it was advertised. Several firms, including three from Dover, put in tenders and the contract was won by Denne of Walmer. He had projected to do the job for £25,000, the lowest tender and that it would be finished within a year. Within hours of winning the contract Mr Denne was looking at the site, which was about half a mile from the Castle where the ground gradually sloped down to the edge of the cliff. When Mr Denne arrived, Major Hardiman met him and already there was a pile of several thousand bricks waiting on the three acre building site. The governor’s residence, Mr Denne was told, was to be to the west of the Prison and to the east, warders’ houses. There would be a prison hospital, a separate laundry, administration block, bakery and engine room. The actual prison was to be three storeys high and the complex surrounded by a 15-foot high solid boundary wall that would be about three-quarters of mile in extent.

The contract also included the building of a road at the back of the proposed prison to a prison yard, which would be down the hill on Northfall Meadow. Additional bricks to those already at the site were to be made by Mr Denne’s firm and would be brought from Walmer by cart to the Lone Tree on the Dover-Deal Road (A258). There they would be transferred onto a horse drawn tramway to the site. The tramway was to be built by the Royal Engineers and this had been arranged with the Earl of Guilford, who owned the land between the proposed prison and the Dover/Deal Road. Stone and timber was to come from Dover and it was hoped that much of the labour for building the prison would also come from Dover. In fact, labourers came from far and wide with many lodging in St Margaret’s. At the same time Royal Engineers were going to create two reservoirs and erect water tanks to the north-east of the prison complex and sewerage tanks to the west.

By this time, it was accepted that the Harbour of Refuge would not be completed for a long time but hopes were raised in April 1885, that the project would soon start when a major survey of Dover Bay was undertaken. This was under the superintendence of oceanographer and hydrographic surveyor Captain Thomas Henry Tizard (1839-1924) of Her Majesty’s, ship Triton. The area covered extended from Shakespeare Cliff on the west to Langdon Bay on the east, the distance off shore was a little over 1¼ miles. On 31 August 1885 the first batch of, 50 convicts arrived at Priory Station guarded by 10 warders. The event was reported by the Dover Express (04.09.1885), who wrote that the convicts ‘were handcuffed in couples and fastened together in five groups of ten by chains. They wore the usual convict garb, red and yellow coats, yellow scotch caps, grey stockings and yellow knickerbockers.’

Although Denne had stated that he would build the three blocks of prison cells within the year, he only completed the ancillary buildings and block, ‘A’ by the end of the year. The remaining two blocks were given over to the Royal Engineers to superintend using convict labour under the watchful eye of armed warders. When the prison was completed block ‘A’ was at the top, the exercise area on the second level together with block ’B’ and block ‘C’, on the level nearer the sea. All were surrounded by a high wall.

A Dover Express reporter, along with a group of councillors, were allowed to look round the prison in May 1886. At the time convicts were laying the steep road from the Dover/Deal Road via Northfall Meadow to the site of the prison – now called South Foreland Road. The visitors travelled in wagons pulled by horses along this road and the reporter tells us that as they passed the convicts, they all stopped work and at the command of the warder turned their backs to the visitors. At the top of Langdon Cliff, the visitors approached the prison gates and were met by several officials, all of whom were ‘gentlemen’. The reporter tells us that on the right of the entrance was a waiting room, opposite which was a large reading room and library for the use of the warders. The visitors then crossed the courtyard, to the right of which were offices, in the centre was the work complex that included the kitchen, laundry and workrooms and on the left, the prison hospital. In front of them was a large building with the letter ‘A’ painted on the wall.

They were accompanied to block ‘A’ by a warder who took out a large bunch of keys and unlocked an iron gate, then a sturdy door before the visitors could gain entry into the building. The first thing that struck them was the cleanliness and airiness of the place. The floor was described as being made of asphalt and that it shone through continual sweeping. The block had three storeys that were open to the centre of the building with iron galleries stretching along the full length and across the two upper floors. The cells were surprisingly large with high ceilings. In each cell, facing the door was a shelf that contained a rolled up hammock with its bedding. Let into the wall of the cells, some two to three feet above the floor, were two eyelet holes from which a hammock was slung at night. Behind the door was a triangular shelf on which, in some cells, were useful books such as Castell’s Popular Educator and Chamber’s Journal. On each cell door was the occupant’s name and number while on the walls outside were ‘notices to convicts’ and a dietary table. Night soil was collected in the morning and each prisoner was responsible for cleaning his own latrine.

The visitors were then shown around the common area on the ground floor of block ‘A’. This housed a large stove for heating the building and a reading stand. On a wall the reporter saw a notice listing which prisoners were allowed to grow their hair and cultivate whiskers. The visitors then left the building and were taken to the kitchen and were met with ‘an appetising savoury smell’. The kitchen was large and contained all the latest implements and cooking utensils. About half a dozen convicts were doing the washing up watched over by a warder. On the table were brown loaves of various sizes, the larger ones being for breakfast and supper and the smaller ones for dinner. The visitors were then told about the daily allowance of food and given the opportunity to see the pantry where it was kept and to taste the beverages. They reported that both the tea and cocoa were of good quality. Near the kitchen was the workroom. There, convicts were employed in shoemaking, bookbinding and darning stockings. In the same complex were the bathrooms where convicts received a weekly ‘tubbing’.

Down the steep incline towards the cliff edge, at the time, two other prison blocks were being built. Prisoners were laying the foundations for prison blocks, ’B’ and ‘C’ and the reporter tells us that ‘… high above them on scaffolds were posted several armed warders, who were not only able to see the movements of the men beneath but had the advantage of taking in at a glance the whole of the prison and some distance beyond.’ Before leaving the prison, the visitors were taken into the prisoner visitors’ room. Immediately in front of them, wrote the reporter, were iron bars that went across the width of the room separating the inmates from their visitors. Set into the wall at the far side of the room, on the other side of the iron bars, was the door by which the convict and warder entered. There were no chairs so all remained standing with the guard standing to one side of the prisoner between him and his visitor. This was to ensure that they could speak to each other but that nothing could be passed. In their report of the visit, the councillors were impressed with what they had seen saying that Langdon prison was as comfortable and agreeable as circumstances would allow.

By July 1887, no decision had been made about the proposed Dover’s Harbour of Refuge and questions were asked in the House of Commons, particularly in relation to the employment of convicts at Langdon Prison. Conservative Arthur Balfour (1848-1930) replied on behalf of the government saying that if the harbour works proceeded they should not be by half measure in a desire to save large sums. He declined to expand further on the future of either the prison or the Harbour of Refuge. A month later the questions were again raised when the Home Secretary (1886-1892) Henry Matthews (1826-1913) stated that £68,000 had been earmarked for the prison project and thus far £49,000 had been spent. ‘That having spent that amount of money it was obvious that the government was going to carry out its intentions.’ He went on to say that the government‘s policy was to take all prisoners, not under sentence of death, out of London and to place them on public works in the country. Another MP, without being called by the Speaker, shouted that Mr Matthews had not answered the question and this was followed by a chorus of ‘here, here.’

In the House of Commons, on 4 April 1888, Dover’s Conservative MP (1874-1889) Major Alexander Dickson (1834-1889) tabled the question asking for the government’s intention regarding both the harbour and the convict prison. The Leader of the House of Commons (1887-1891) William Henry Smith (1825-1891) – later Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports – replied saying ‘that it was not the intention of the Government to proceed with the harbour in question.’ Stunned, Major Dickson questioned the cost of the prison thus far and its future purpose, William Smith replied that the total expenditure had been £61,575 10shillings 9pence. Of which £48,400 5pence had been spent on buildings and £13,175 10shillings 4pence for land. Mr Smith went on to say that although the prison had been built to supply labour to build a Harbour of Refuge, that there were doubts over Dover being the best place for such a harbour and it was for this reason it was considered to suspend further outlay.

In Dover, both the Harbour Board and the Corporation looked at other means to build the badly needed Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour. Meanwhile at Langdon prison, it was business as usual. In 1889, the staff consisted of Governor – Captain F Johnson, Deputy-Governor – Captain W E Balle, Chaplain – Rev. John Core Tipper, Medical Officer – H Smalley, Assistant Surgeon – C H Mayhew, Steward – M D Hogg, Foreman of Works – G R Waters and Chief Warder Seymour. The number of inmates was 102 and their main occupation was sewing mailbags. Dover Harbour Board, on 3 October 1890, again applied to parliament for permission for them to build a Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour and for it to be built by a private contractor using ordinary and convict labour. All the government departments except the Admiralty gave approval for the harbour project while the Home Office withheld their support from using convict labour.

At the time what became the Penal Servitude Act of 1891 was going through parliament. This enabled Courts to pass sentences of three years and upwards, instead of a minimum of five years. Not only was this expected to reduce the prison population but would also reduce the need to find outside employment for prisoners that was giving rise to discontent from the unemployed. Work started on the eastern arm of the Dover Harbour of Refuge/Commercial harbour – this became the Prince of Wales Pier. The contract was given to Sir John Jackson of Westminster but approval for the use of convict labour was not forthcoming. Four years later, in 1895, the prison population at Langdon had been reduced as prisoners were starting to be moved to other prisons. The staff remained and government officials reassured the town that the prison was not going to close.

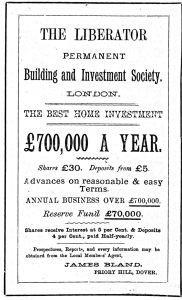

Liberator Building Society Advert of 1887 in Dover’s press giving James Bland of Priory Hill as the local agent.

This appeared to be confirmed when the prison received its most high-profile inmate Jabez Spencer Balfour (1843-1916). Balfour had been the Liberal Member of Parliament for Burnley (1889-1893) and before then had been an MP for other constituencies. In 1867 he founded the Lands Allotment Company, the following year the Liberator Society that purported to be a building society. These were followed, in 1875, by the House and Land Investment Trust. By the interchange of cheques between the three companies he and his associates had produced sufficient paper profits to attract small investors. More companies were then set up and the paper profits continued to increase, some buildings actually saw the light of day. All of which attracted thousands of small savers, mainly working men, shop keepers, professional men, ministers of religion and women of slender means. In 1892 one of the companies collapsed and by the end of that year they all had, with total liabilities of £8,360,000. All the small savers lost their money. Balfour disappeared and turned up in Buenos Aires three months later. The extradition proceedings took two years then in May 1895 he was charged at Bow Street magistrates court and following the subsequent trial was sentence to 14-years penal servitude for conspiracy and fraud. The collapse of the Liberator group of companies led to the 1894 Building Societies Act that required Societies to keep and present full accounts, to maintain lendings at a manageable proportion to deposits and for them to be used for the purpose as laid down in the Building Society Acts. In November 1895 Balfour was incarcerated in Langdon prison.

While all of this was going on, parliamentary approval was being sort for the Undercliff Reclamation Bill, the main given purpose of which was the prevention of sea erosion at the base of Dover’s Eastern Cliffs. In early 1895 there was a severe frost, lasting several days, that had caused a number of cliff falls along the stretch of coast between Dover and St Margaret’s Bay. In February 1895, Chief-Warden Luxon was almost killed when he was returning to the prison from East Cliff by way of the then Northfall Tunnel. As he was about to emerge at the prison end, there was a massive cliff fall that eventually blocked the exit. Luxon managed to escape but there were fears that ‘C’ block may succumb to a cliff fall and it was evacuated. In their evidence to Parliament on the Undercliff Reclamation Bill, Dover Corporation showed that over the previous 25 years the encroachment of the sea had given rise to numerous cliff falls along that stretch of the coast. To build such a wall, they said, would be an excellent use of convict labour.

The Undercliff Reclamation Bill, was in fact a private business venture sponsored by Sir William Crundall (1847-1934) – thirteen times Mayor of Dover from 1886 to 1910 and Chairman of Dover Harbour Board from 1906, Sir John Jackson – who was building the Prince of Wales Pier and Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray (1856-1927) – the eminent construction engineer. In reality, the ultimate purpose of the Bill, as far as the three men were concerned, was not the prevention of sea erosion at the base of Dover’s Eastern Cliffs but to build a road to St Margaret‘s where they planned to develop an exclusive housing estate made up of palatial detached homes in extensive grounds. (See Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Railway Line – Part I).

Dover Corporation, Dover Rural District Council, St Margaret’s Parish Council and the editor of the Dover Express, John Bavington Jones all recognised what the three developers real intentions were. They all backed the Bill as it was the only way they could see a seawall being built. Further, they all guessed that if convict labour was not used, the three developers were likely to take the road over the cliffs, which was a cheaper option. For their part, government cabinet ministers and department officials were at great pains to reassure the different councils and Bavington Jones that prisoners were being moved out due to the closure of block ‘C’. They also implied that the move was to make room for more robust convicts, who could tackle the hard manual work required to excavate the Undercliff. Further, according to Bavington Jones, the Labour Party’s Keir Hardie (1856-1915) along with Trade Unionists John Elliot Burns (1858-1943) and Henry Broadhurst (1840-1911) were prepared to back convict labour being used along with skilled labour to build a seawall and road to St Margaret’s.

Dover Harbour 14 July 1903 Prince of Wales Pier. To the right is the Admiralty Pier. Wellington Dock nearest the camera with Waterloo Crescent and Esplanade. Nick Catford

In Parliament, Herbert Asquith (1852-1928) – the Home Secretary (1892-1895), announced that although the Penal Servitude Act was reducing the prison population, the provision of free labour by convicts was causing discontent amongst the unemployed. This being so, he was very much against convicts being used for what was private enterprise. In the autumn of 1895, the Home Office announced that ‘Owing to the decision not to proceed with the Harbour of Refuge by convicts, there has been no outdoor employment for them at Dover…’ Langdon prison was to close on 30 January 1896. In May 1895, when about three-quarters of the Prince of Wales Pier had been completed, the Admiralty announced its decision. It was going to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy and that an Admiralty Harbour would be built by private contractors to enclose Dover Bay!

Balfour, in January 1896, was one of the last prisoners to leave Langdon Prison. He was transferred to Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight and due to exemplary conduct was released after 10½years. At Easter 1897, the former convict prison housed some 3,000 Surrey Brigade of Military Volunteers who had come to Dover on a military training exercise. The Admiralty Harbour, we see today, was given the go ahead and on 9 November 1897 it was announced that Viscount Cowdray’s company – Pearsons, were to be the main contractors, Sir John Jackson was a subcontractor and Dover Harbour Board, under Sir William Crundall, was to be actively involved.

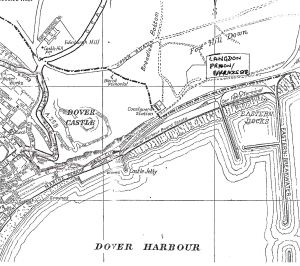

Langdon Convict Prison / Broadlees Military Prison Langdon Cliff Map c 1903 showing location. Note reservoir caption & the proposed road to St Margarets. Dover Library

When work on the Admiralty Harbour was started the Northfall Tunnel was closed and a pathway was excavated with the prospect of it eventually becoming a broad road connecting Dover to the South Foreland. A subterranean tunnel, from the precincts of the old prison to the beach below, was hewn within the cliffs and parallel water pipes were laid. The water was piped from the prison reservoirs to the Eastern Arm building site. Besides the reservoirs on maps of that time is the statement, ‘Soft water for use by the Admiralty.’ This has been interpreted to mean that the water was to be used for ship’s boilers, as hard water was not suitable. The Martin Mill – Dover light railway line was cut across the cliffs to carry shingle for the construction of concrete blocks at what became the Eastern Dockyard and passed close to the prison site. On reaching the cliff edge, the wagons were emptied into side tipping skips that were taken down the cliff face on a funicular.

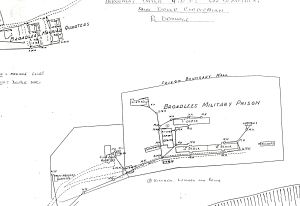

In March 1899, it was rumoured that Portland Prison, Dorset, was to close and that the convicts there were to be moved to Dover. This turned out to be speculation for although inspectors from London were looking at the prison on Langdon Cliffs, this was for other purposes. In September 1900, the War Department announced that they were going to use the Broadlees Prison complex – the new name for Langdon Prison – as a military prison for the South Eastern, Woolwich and Thames District. On the recommendation of the inspectors representing the Military Board, alterations of an extensive character were going to take place to make the buildings suitable before prisoners could be moved in.

Work started almost immediately with’C’ block being demolished, and the cells in ‘B’ block made larger by knocking two cells into one. The former ‘B’ block was extended eastwards with a separate equal size annex. These two blocks were renumbered ‘A’ and ‘B’ block and the former ‘A’ block renumbered ‘C’ block. In August 1901 official approval was given for the New Military Prison by the Secretary of State for War, William St John Broderick (1856-1942). It was reported that the prison would be under the superintendence of a full time army officer graded as a military governor second class. Further, the person chosen would be fully aware of the ‘more enlightened system of military prisons that was being introduced.’ Under this system, prisoners were treated more like soldiers than criminals so that they would be useful members of the military establishment.

Broadlees Prison, Langdon Cliff Agreement between War Dept & Dover Corporation re Drainage 09.12.1903 – Dover Library

At the time, Britain was heavily involved in the Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa, and this had given rise to 1,377 convictions with most serving their sentences in South Africa. It soon transpired that the prisoners to be sent to Broadlees Military Prison were those who had been sentenced to heavy terms of imprisonment at the Front. Generally, they were said, to be very dangerous characters who had committed atrocities of the worst kind. Further, even though the prisoners were of such character, they were still to be treated more like soldiers than criminals and once they had served their sentences they were to be discharged from the army. Another announcement stated that Broadlees was to be the largest military prison in the country and further building work included the only two buildings still standing, these were at the eastern end of the prison. A stable block was built next to the Governor’s house, a house for the Chief Warder and a married quarters block for prison warders to the north-west. Not long after 380 cells were certified for use.

The criminal-soldiers started arriving by the end of 1901 having been brought from South Africa by ship with most disembarking at Dover. They were handcuffed, had shackles around their ankles and walked from the harbour to Athol Terrace at the base of the Eastern Cliffs. They then had to climb the steep path that had been recently excavated, to the prison gates. It was reported that locals felt sorry for the prisoners, as the shackles around the ankles made it difficult for them to climb up the steep path.

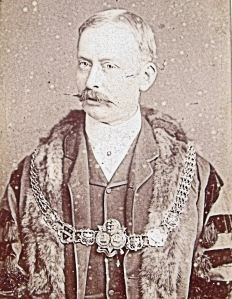

Field Marshall Lord Frederick Roberts (1832-1914) being given the Honorary Freedom of Dover 28 August 1902. Dover Museum

Of the prisoners sent to Broadlees Prison at this time, five had separately been found guilty of sleeping at their posts. Field Marshall Lord Frederick Roberts (1832-1914), Commander in Chief of the Forces, had been asked to look into their cases as it was believed the punishment was far in excess of the seriousness of the crime. The Field Marshall did as he was bid and found that they had all been found asleep and had therefore put in jeopardy what they had been assigned to guard. However, in each case the men had been on duty in excess of 24hours, without a break and including having to relieve themselves while at post. The results of his inquiries were passed on to the relevant authorities and their convictions were over-turned on the grounds of mitigating circumstances. The soldiers were released on 3 September 1902, a week before Lord Roberts received the Honorary Freedom of Dover.

It was about this time that the prison was up-graded from a second class Military Prison to a first class one and Major G.S. Haines was appointed governor. Major C.C. Daniels of the Royal Scots succeeded as prison governor in May 1904 and on 13 August 1904 a prisoner named Taylor asked to see him. At the interview, Artilleryman Taylor confessed that he had committed the Peasenhall murder and that it was preying on his mind so much that he could not think.

The murder had taken place in the village of Peasenhall, Suffolk on 31 May 1902. At about midnight Rose Harsent, a servant girl, had her throat cut and sustained deep gashes to her shoulders. She was unmarried and six months pregnant. After a police investigation William Gardner, a church stalwart and foreman at the local seed drill works was arrested. The father of six children, Gardner had an affair with Rose in 1901 but at the time of Rose’s death, he was at home in bed with his wife who staunchly corroborated this.

Gardner was brought to trial at Ipswich, Suffolk on 7 November 1902. The prosecutor was Henry Fielding Dickens (1849-1913), a son of author, Charles Dickens (1812-1870). He was also Deal’s Recorder. The jury reached a verdict of 11 to 1 in favour of conviction. In those days, for a conviction to be acceptable the jury had to be 100% in agreement. Gardner’s retrial took place on 21 January 1903, again the prosecutor was Dickens, but this time the 10 out of the 12-man jury returned the opposite verdict of not guilty. Instead of yet another retrial, Dickens’ offered a writ of nolle prosequi, which meant that Dickens had declined to further pursue the case against Gardner.

Artilleryman Taylor, the prisoner at Broadlees, came from Peasenhall and had, in 1903, been found guilty of enlisting using fraudulent papers. Superintendent Staunton of Suffolk County Police came to the prison and interrogated Taylor. It was evident to him that Taylor had detailed knowledge that would only be known to someone closely involved and the interrogation finished with Taylor signing a confession. This, along with the Superintendent’s report, was sent to the Home Office. A few days later it was reported that neither Superintendent Staunton nor Major Daniels had believed that Taylor was the murderer and the case against him was closed. It later transpired that Rose was a flighty lass who had a string of lovers but these days it is generally thought that her murderer was Gardner’s wife.

In September 1907 it was announced that the Broadlees Military Prison was to close and that no more prisoners were to be sent there after 1 October that year. It was finally closed on 28 February 1908 when the eighteen remaining prisoners were removed to Woking prison. Locally, two sets of speculations abounded. First, that the buildings were to be converted into barracks, but even the speculators recognised that this would require extensive internal gutting and rebuilding. The alternative view was that as the site actually belonged to the Prison Authorities and was on loan to the War Office, it was likely to become a civil prison. All speculation ceased when the Home Office announced that the prison was to be used for juvenile offenders under a special system that had been introduced in 1902, at Borstal Prison, Rochester. The Home Office planned to re-open Borstal prison as an ordinary convict establishment.

At this time, the War Office was concerned at events in Europe. In 1890, Germany, under Wilhelm II (1888-1918), had been pursuing a massive naval expansion. It was this that had galvanised the British government to build the Admiralty Harbour as a base for the Royal Navy and in 1900, at the prison, an observation post was built next to the tunnel going down to the seashore. The juvenile offenders institute project at Langdon was abandoned and as World War I (1914-1918) loomed the Admiralty ordered the prison to be converted into Naval Barracks. Besides housing naval personnel the site became a military transit camp for troops going to the Western Front.

To help protect the Admiralty Harbour from attack, a cave was excavated part-way down the tunnel to house Langdon Battery, which was equipped with three 9-inch guns. To the east, three searchlight batteries were installed with generators nearer the seashore in order to illuminate passing ships for identification. They were accessed by a steep zigzag path, known as the Langdon Stairs or from Fan Bay beach below by a ladder. During the War a medical centre was built next to the observation post in the former prison compound and at about the same time the water pipes from the reservoirs were strengthened. The water was for use by naval vessels moored in the Camber in the Eastern Dockyard. In February 1918, a ship aiming shells at Langdon Battery hit the former prison injuring two soldiers.

East Arrow Block just below the Castle and demolished in 1984. The photograph shows the excavation of the A2 Jubilee Way in the 1970s and the coastguard cottages nearer to the camera. Dover Museum

Following the War, work started on converting the Castle infantry quarters. This included building four blocks of new quarters on the cliff just below the eastern side of the Castle. To save money, bricks and other materials from the former prison were utilised. A small tramway was laid, worked by motors and wire ropes, that hauled the wagons down the hill from the prison site and up again to the construction site. On 25 July 1924 the demolition of block ‘C’ began and by the end of 1925 the East Arrow Block, as it was named, was completed. The complex was demolished in 1984 and the photograph on the right shows the excavation of the A2 in the 1970s with the East Arrow Block below the Castle and the coastguard cottages nearest the camera. Back in 1925, only the former governor’s and chief warder’s houses the prison hospital, some storage buildings and the strong prison walls, of Langdon prison remained. The former prison site was again renamed, this time to Langdon Barracks. The former governor’s house was named Mount Kemmel and the chief warder’s house became The Red House. Langdon Barracks were given over to the Coastal Defence Artillery to be manned by the Territorial Army (TAs), supported by a small artillery unit from the regular Royal Garrison Artillery who permanently occupied the Barracks.

At the beginning of World War II (1939-1945), Mount Kemmel was commandeered as the headquarters of the Royal Artillery 75th Anti-Aircraft Regiment, who were manning the Dover batteries. The Red House became the home of the Master Gunner and his family, the hospital became the Sergeants’ Mess and the other building were used for storage. Again, the tunnel from old prison to the beach and Langdon Battery was re-equipped with defensive measures. Langdon Hole Deep Shelter was excavated and comprised of two parallel tunnels lined with steel and with iron girders for support. The water pipes from the reservoirs were extended to the end of the Eastern Arm to provide running fresh water for the staff and the Batteries there. Towards the end of the war through to 1948, Langdon Barracks were used for German prisoners-of war awaiting repatriation.

One of the two former Prison buildings at Langdon Cliff that are still standing. The plaques give date of construction as 1902 and refurbishment in 1995. A Sencicle

Early in the 1950s the entire former prison site, with the exception of the two 1902 buildings, was cleared. Dover Harbour Board demolished the old reservoirs and constructed two new ones to the rear of the 1902 buildings. The new water pipes had wider apertures than the former ones and they were carrying considerably more water from 330-feet above the Eastern Docks, a pressure break tank was built about 115-feet above the dock buildings. In 1989, it was reported that the daily consumption of water from the reservoirs at Eastern Docks was approximately 300,000 gallons a day!

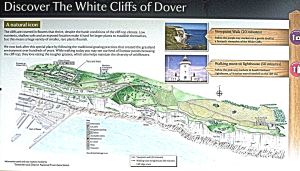

Dover Rural Council, in 1959, accepted a suggestion by the War Department Land Agent that they should take up the lease of 25 acres of land at the top of the Eastern cliffs. It was also suggested that the site of the former Langdon Prison should be laid as an official car park and public open space. Unfenced, the site became a favourite place for parties and occasional public concerts. Following the successful outcome of the referendum to join the European Community in 1975, a massive party was held on Langdon Cliff! The site was transferred to Dover District Council (DDC) in 1974, following Local Government Re-organisation but due to legal complications the transfer was not completed until 14 April 1976.

In order to raise money to pay for the ill-fated White Cliffs Experience, DDC, in the 1980s earmarked the former prison site for redevelopment but following the National Trust buying five miles of Eastern cliffs coastline, through its Operation Neptune Project, DDC gave it to them. As the area is rich in chalk-turf species such as horseshoe vetch, sheep’s fescue, salad burnet, wild thyme, wild carrot and alexanders, in the early 1990s the area was designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). In 1995, the two remaining buildings from the old prison were restored and are now used for administrative purposes. The land has been landscaped, laid out with walks and car parks and in 1999 the visitor centre and café opened. A permanent team of staff supported by volunteers’ run the complex. The National Trust’s main aim is to get visitors to appreciate the surrounding countryside and the areas history and visitor information panels have been erected. Much of the finance is raised locally, by the volunteers and special events.

The visitor centre is open daily throughout the year excluding Christmas Eve and Christmas Day and offers a selection of homemade lunches and cakes. Free maps are available at the visitor centre that shows the walks over the cliffs to South Foreland Lighthouse, which is also well worth a visit. En route there is the Fan Bay Deep Shelter (see Swingate story part II) and both the Lighthouse and the Shelter are open four days a week from Easter to October.

For more information: http://www.national.trust.org.uk/the-white-cliffs-of-dover

- Presented: 14 March 2016