In the 1840s, Europe was in a major economic depression, discontent was rife and the atmosphere revolutionary. In England, the Chartist movement, demanding political and social reform, were increasing and the Establishment were looking for ways to avert troubles. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort, suggested that businessmen should set up Societies in order to improve or build working class dwellings using the 1836 Improvement Societies Act.

In Dover, Mayor William Clarke, (1845-6), set up the Dover Investment and Mutual Building Society – a Terminating Society. The first Terminating Society had been instigated by a Birmingham pub landlord, Richard Ketley. In 1775 he had set up a central fund for a limited number of his customers that paid a monthly subscription. When sufficient money was raised to buy a house, a ballot was held and one of the customers used the fund to purchase his home. He repaid what he owed over a pre-determined period while in the meantime, when further sufficient funds accrued, a second persons name was drawn and so on. Once all the members had a house, the ballot scheme was dissolved.

At Buckland, Reverend Samuel Tennison Mosse persuaded a group of local businessmen to set up the Dover Cottage Building & Improvement Society. Sir Brook Bridges MP headed this and Rev. Mosse was the Honorary Secretary. They opened for business at 3 Snargate Street in May 1846 and their first major project was financing the building of five pairs of ‘model’ cottages in Buckland. This was followed by the building of Brookfield House, as a master’s residence for Buckland School. They then purchased of land from the Department of Woods and Forest and built Castlemount Cottages – the start of Castlemount Road on land owned by Robert Chignall, who built Castlemount.

In June 1846, the Dover and East Kent Building Society (DEKBS) displayed their rules in the old Town Hall, then in Market Square, showing that it too was raising money in order buy land and build on which the investors could expect a lucrative return. This did not go down well with Dover Investment and Murtal Building Society (DIMBS) – who saw DEBKS as adopting all their ideas without adding anything new. The treaurer of DIMBS was solicitor Edward Knocker who made his views felt at a special meeting. Nonetheless, DIMBS did manage to sell 300 shares and then joined in with DEBKS. The chairman of DEBKS was Lewis Stride of the National Provincial Bank and the secretary, John Knocker – brother of Edward – was the manager of the London County Bank. The business attracted a number of wealthy depositors and with this, the DEKBS purchased much of the land on the west side of the then York Street. There cottages were built some of which still stand today on Cowgate Hill.

Both the Cottage Building & Improvement Society and DEKBS were embryonic forms of what became Permanent building societies. It was quickly realised that it was safer to spread the funds by lending to those who wished to purchase their own homes. On 12 March 1850, the Dover Permanent Benefit Building Society (DPBBS), absorbing the Dover Cottage Building & Improvement Society, opened for business with this in mind.

Dr Edward Farrant Astley chairman of the Dover & East Kent Building Society reconstituted 1855 – Dover Museum

In 1855, the DEKBS followed suit and was reconstituted becoming a Permanent Society (DEKPBS). Dr Edward Ferrand Astley was appointed chairman and Henry Strong Boyton, secretary. There were 18 directors one of which was Thomas Achee Terson and the Society operated out of Terson’s office, then 6 Castle Street.

Henry Strong Boyton was Louis Stride’s cashier at the National Provincial Bank and remained the secretary of DEKPBS until his death in 1916. For much of that time DEKPBS was referred to ‘Boyton’s!’ At the time the minimum contribution to building societies was usually 10s (50p) a month, which most working class people could not afford. So Henry Boyton introduced a 2s 6d a month saving scheme – the first in the country. Boyton’s (DEKPBS) were also one of the first Societies making direct loans to their women savers.

The Dover and District Building Society (DDBS) was launched in September 1861 offering similar terms. The trustees included Richard Dickeson, Alfred Kingsford, James Worsfold and local architect Edward Wicken Fry. The secretary was Christopher Kilvington Worsfold, whose offices were at New Bridge. DDBS differed from their Dover rivals by giving priority to applicants wanting to borrow £200 or less. They also set limits on legal expenses so those clients knew in advance the full cost of their borrowings.

By the 1870s, problems were emerging that needed to be addressed by legislation. For instance, there was a tendency for the ballot winner of Terminating Societies to sell the property for a profit without any benefit accruing to the other members still waiting to buy. Some of the trustees of Permanent Societies gave themselves such huge bonuses that forced the business into liquidation with the savers liable for the debts. While, others failed to maintain sufficient reserves and they were unable to borrow to meet increases in demand for mortgages or /and increases in property/land prices.

The Trustees of DDBS were particularly vociferous for legal clarification that finally culminated in the Building Society Act of 1874. Terminating societies and their direct successors, Mutual societies – where the depositors and the borrowers were the same, were described. The Act also demanded that all new building societies were to be incorporated and existing ones on statutory application. Members, borrowers and lenders were freed from liability when societies were wound-up but trustees/directors were personally liable. Societies were allowed to borrow up to two-thirds of the amount secured by mortgages from the members but if they exceeded that, the trustees/directors were again accountable.

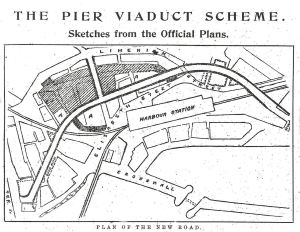

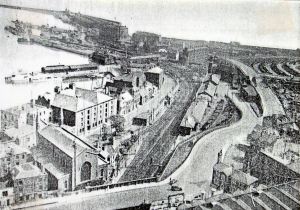

Following the Act, DDBS incorporated to include Permanent (DDPBS) in their name, Christopher K Worsfold remained the secretary, and Edward Wicken Fry was the chairman. Their stated objectives now included the raising of capital to build housing for the working classes and in 1886 set up the Dover Artizans and Labourers Dwelling Company Ltd. Henry Hayward, a partner in Worsfold and Hayward, 3 Market Square was the secretary. The Company built the Artizans, later Victoria, Dwellings, in the Pier District. Costing £5,000 the dwellings was a large five-storey block of flats designed by Peabody Buildings in London and rented to local workers.

On 8 June 1883 the Dover and Folkestone Permanent Self-Help Building Society (D&FS-HBS) was established at Pencester Hall, 20 Biggin Street – where Marks and Spencer’s are today. The first secretary Mr H R Barker of Tontine Street provided the Folkestone interest. They later moved to Priory Place, Folkestone Road, then to A.T.Blackman’s offices in the High Street.

Under the 1874 Building Society Act, the Dover and District Ballot and Sale Society, secretary G W H Toms, opened in 1890 at 21 Park Street. It had folded by 1905. During the latter part of the nineteenth century, a group of local businessmen, headed by architect and auctioneer, Vernon Shone of 6 Market Square, set up the Dover Mutual Building Society to built Victoria Park. The depositors and borrowers were mainly senior army officers stationed in Dover. The Society later advertised that it was incorporated under the 1894 Building Societies Act.

This Act came about following the collapse of the Liberator Mutual in 1892. That society had accepted more than a £1m of funds through their countrywide outlets – including one on Priory Hill. A former Liberal MP, Jabez Spencer Balfour, ran the scheme. He had lent money to companies that bought properties, at an inflated price, owned by himself. Of interest, Balfour was tried at the Old Bailey and sentenced to 14 years in prison. Part of his sentence was served in Langdon Prison, on the Eastern Heights, giving the place a certain amount of fame!

The 1894 Act required Societies to keep and present full accounts, to maintain lending at a manageable proportion to deposits and for them to be used for the purpose as laid down in the Building Society Acts. The Act also brought Mutual societies into line with the Permanent ones.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Dover besides the different forms of building societies there were a number of Friendly Societies lending money for house purchase, to their members. In 1910, the Dover Oddfellows reported that 300 members were buying their own homes and a further 50 members had paid back their loans in full.

The post- World War I economy left little room for home buying and by 1929, just four of Dover’s building societies remained. They were the Dover Permanent Benefit Building Society (DPBBS), Dover and District Permanent Benefit Building Society (DDPBS), Dover and East Kent Permanent Benefit Society (DEKPBS), and the Dover and Folkestone Permanent Self-help Building Society (D&FS-HBS).

In 1931, in order to try to get savers to put their money in their Society, the DDPBS voted to change its constitution and introduced Paid-Up shares of £100 each. The idea worked and by 1939, their total assets were over £100,000.

On 5 March 1936 Thomas Achee Terson, the chairman of DEKPBS died and that year George Norman, son of George Madgett Norman – the Mayor at that time – joined Terson’s as an office boy. In addition, in 1936, the D&FS-HBS was renamed the Dover and Folkestone Building Society (D&FBS) and amended its constitution. Norman V Sutton, later editor of the Dover Express and father of newspaperman, Terry Sutton, joined the board of directors.

During World War II, much of the business of building societies was curtailed. Albeit, the expected withdrawals to pay for house repairs was offset by the 1941 War Damages Act as the Government provided grants for such repairs. Following the war the Act was extended but lack of savings and inflationary pressure took its toll on societies.

One such society was DEKPBS that celebrated its centenary in 1946. On the 30 December that year a special meeting was called and Sydney C Clout, announced that the assets were £108,984 7s 9d but that Society was to amalgamate with the Alliance Building Society of Brighton. The three other Dover building societies managed to keep going and in March 1950, the DPBBS, with offices at 32 Castle Street, celebrated its centenary at the White Cliffs Hotel. The night it was announced that its assets were £150,000.

Terson’s acquired 29 Castle Street in 1953 and the D&FBS moved in. The following year the firm’s sole principal was given as George Norman. In 1959 John S Lewis, Chairman of the Directors of the building firm of G Lewis & Sons, and of Messrs Lewis Brothers the motor engineers, Cherry Tree Avenue, died. He was also chairman of the DPBBS the office of which had moved to 49 Castle Street.

The following year, DPBBS merged with the Hastings and Thanet Building Society, which was later taken over by Anglia then Nationwide. March 1977 saw the 116-year-old DDPBS merge with Chatham Reliance, which in 1986 became the Kent Reliance Building Society. In April 1978, Dover’s remaining building society, the D&FBS moved to 35 Castle Street, which it owned.

Norman Sutton retired as vice-chairman of the D&FBS; he died in 1986. The former principal of Terson’s, George Norman, was chairman when, in March 1984, it was agreed by 354 votes to 13 to merge with the Yorkshire-based Bradford and Bingley Society who took over the premises in Castle Street . . . the Society had been operating ninety-nine years.

Published:

- Dover Mercury: 18& 25 October & 01 November 2012

For further information on Castle Street : http://www.castlestreetsociety.co.uk