These days most of us drink ubiquitous branded aerated mineral waters. Once upon a time locals would only drink aerated water manufactured in the town and Dover had a thriving industry for local and national consumption.

George Forster, of 52 Castle Street, (now Blakes) opened his business as a chemist in 1834 and later expanded it to include the manufacture of aerated mineral water, including soda water, lemonade and ginger beer. However, it was Stephen Read Elms, age 34, who in 1837 opened Dover’s first aerated waters factory.

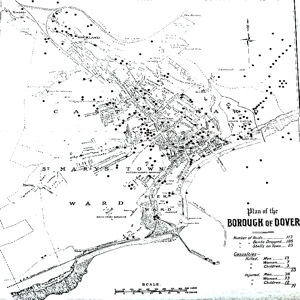

This was in Branch Street, Charlton, between the High Street and, nowadays, Morrison’s delivery yard. Nearby, was, and still is but running into a culvert, a chalybeate spring – water containing salts of iron that had been discovered in the 18th century. Indeed, the drinking of waters from this spring had turned the tiny village into a budding health spa. If it had been allowed to develop, Charlton could have grown to become a rival of Leamington Spa! However, a paper manufacturer opened a short-lived paper mill and the spring was diverted into the culvert in order for the water to be used for papermaking.

Stephen Elms came from Canterbury where he had learnt his trade and Charlton was attractive to him on two counts. The first was other springs and second, there were no aerated water factories in Dover. Stephen’s business was a success and he eventually diversified into making a large variety of sweets for the local market. Stephen died in 1872 but before then his son, also called Stephen, and was heavily involved in the running of the company. It is from Stephen junior’s time that a detailed account still exists of the manufacture of aerated water at the factory.

The basic drink, made up of water, sugar and flavourings, was brewed in large copper pans heated on giant gas rings until the sugar dissolved. The mixture was allowed to cool and then effervescence was added. Manufacturers of fizzy drinks for much of the nineteenth century used either seidlitz powders – a cathartic made up of a mixture of tartaric acid, sodium bicarbonate and potassium sodium tartrate; or citrate of magnesia, a laxative.

By the end of the century, large concerns were using carbonic acid gas, and this is what was being used by Elm’s at the time of the detailed account. The gas was purified carbonate of lime mixed with an acid to create the effervescence and introduced into the drink using a generator. The next part of the process was bottling the aerated water and sealing the bottle.

When the factory first opened in 1837, the liquid was poured into the bottles and corks were pushed in and secured by wire – in the same way as champagne corks are today. Although some manufacturers still used that system, Stephen junior used Codd-neck bottles together with Bennett & Foster bottling machines.

The Codd-neck bottle, patented in 1872 by Hiram Codd of Camberwell, was of heavy glass with a glass marble inside and a ring of rubber at the neck. Using the Bennett & Foster machine bottles were filled with the carbonated drink and once filled, the machine turned them upside down. The marble fell into the neck against the washer and was kept there by the pressure of the gas. The customer released the drink by pushing the glass ball into the slightly wider neck of the bottle either with a special implement or with their finger.

A good operator could fill and seal about 280 bottles an hour but considerable care and judgement was required as there was always the risk of a bottle exploding causing serious injuries from fragmented glass. Although Codd neck bottles are still used in some countries they were discouraged in the early twentieth century because of the danger involved.

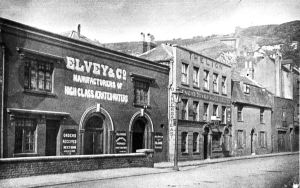

By the last decade of the 19th century, there were seven firms in Dover producing aerated water: Bright of Caroline Place; Elms in the High Street / Branch Street; Elvey in Limekiln Street; Foster in Castle Street; Jones in Elizabeth Street; Meenagh on Priory Hill and Souter & Mackenzie & Co in Blenheim Square.

Whether these manufacturers used the traditional or the Cobb-neck bottles, they all faced the two problems. The first was that the bottles were expensive and second, unscrupulous people filled empty bottles with bogus concoctions and sold them as the real thing. To secure the safe return of bottles, the names of the aerated water manufacturer embossed and people paid a deposit that was returned to them when they brought the bottle back.

In order to try and prevent the bottles being filled with poor quality substitute drinks, the East Kent aerated water manufacturers formed a Society. Shopkeepers, publicans and other retailers were advised to only buy aerated water direct from them and to ensure that only their products were delivered each manufacturer had horse-drawn commercial vehicles with their names emblazoned on the side.

Stephen Elms junior died in 1897 and appears to have been succeeded by a daughter and three nephews but the business eventually ceased. Early in 1910, Alfred Leney, Chairman of the Leney’s Brewery, recognising the profitability of supplying their many licensed pubs with soft drinks and opened a mineral water department at his Phoenix Brewery in Castle Street. So successful was the venture that two years later the company opened a factory in Russell Street. The arch on the east side of the Street was the entrance to the factory.

However, on 9 March 1916 at 14.00hrs, a German seaplane dropped a bomb that completely wrecked the factory and it had to be rebuilt. The firm also opened a second factory in the Chalk Pit, Tower Hamlets. In their adverts, the firm boasted that they used pure water from a stream in the chalk bed accessed by artesian well and a motorised pump. Later, Leney’s excavated the caves around the pit and used them for storing the mineral water and in World War II, they were used as air-raid shelters.

When Leney’s amalgamated with Fremlins in 1926 the table water side of the business became a subsidiary adopting the trademark, ‘Pharos’. With the threat of war in 1939, the basement of the Russell Street factory was adapted as an air raid shelter to accommodate 140 people. On 5 July 1943, the factory was hit in the early hours of the morning but luckily, there were no casualties and the building was repaired.

Souter & Mackenzie & Co had the largest mineral water factory in Dover. It was owned by Edwin Souter from Surrey and Patrick W J Mackenzie, from Birmingham. Edwin came to Dover in the 1870s residing in Hawksbury Street, in the Pier District. He opened his factory, employing three men, in nearby Blenheim Square. The entrepreneurial Patrick joined him and the firm quickly grew with factories in Folkestone and Deal.

Patrick Mackenzie, shortly after his arrival, was assimilated in the town’s politics, becoming the Chairman of the Board of Guardians, Magistrate and Town Councillor. However on 6 November 1913, following a stay in a hospital in Birmingham, he went to Kings Norton, Staffordshire, where he died. At the time of his death, Patrick was in sole control of the factories but following his death, the business appears to have been run by a series of managers. The company was still thriving when Edwin Souter died suddenly on 10 August 1922. He was aged 81 and died at his home, Tabernacle House, Maxton and was buried in Charlton Cemetery. After that, little is on record and by 1934, the Souter & Mackenzie factory was derelict so demolished.

Nearby, in Elizabeth Street, in the early 20th century there were three mineral water manufacturers one of which was Elvey’s. Richard Vine Elvey was born in 1865 the son of a bricklayer living in Charlton and it appears that he may have learnt his trade working for Elms. He then joined W Welsford and as the Dover Brewery Company they produced bottled beer, aerated waters and associated products. The partnership was dissolved in 1888 and Richard, together with a series of partners, built up the Elvey Company. What appears to have been Richard’s final partnership before he died on 2 September 1941, was dissolved in April 1939.

Following World War II, Elvey’s along with Leney’s and Ozonic at 13 Priory Gate Road, were still operating. During the rise of the jukebox era, Leney’s secured a contract with Coca-Cola and it looked as if Dover’s aerated waters industry would not be lost. However, in February 1960 Leney’s table water factory closed and aggressive marketing by national and international concerns ensured that by 1970 aerated water was no longer produced commercially in Dover.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 11 & 18 April 2013

For further information on Dover’s Pubs: http://www.dover-kent.com