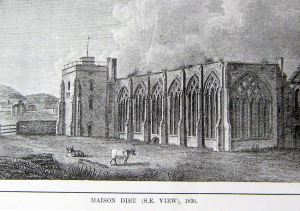

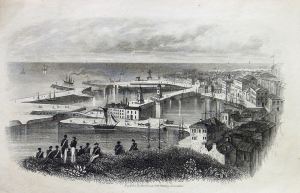

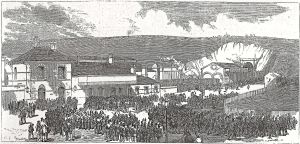

At noon on Saturday 14 July 1883, a Royal Salute announced that the third son of Queen Victoria, HRH Prince Arthur Duke of Connaught and his wife, Louise, had arrived by train at the Town Station. This was in the then Pier District of Dover and they had come to open the newly built major extension of the then Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu, and a municipal park, both to be named after the Prince.

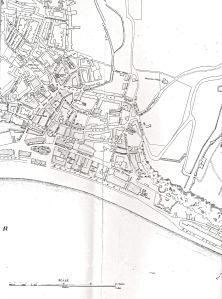

The idea of a municipal park had been muted in the 1860s when land holdings, belonging to the government’s Department of Woods and Forest Department, was put on the market. Charles Gorley, who farmed the land, bought it and built a terrace of villas running from the opposite side of the River Dour at Ladywell to Charlton Back Lane, later renamed Maison Dieu Road. Initially the new road was to be named Ladywell but as the deeds stated the site was part of Maison Dieu Park it was given the name Park Street. This was a cause of embarrassment, as the town did not have a municipal park!

On the slopes below the Castle, in 1876, builder William Adcock was commissioned by Robert Chignell (1837-1923) to build a high-class preparatory school for boys who would later go on to a Public School. Called Castlemount, Chignell had the extensive grounds terraced with lawns, plants and trees and following the express of interest, invited the public to come and promenade at weekends and at times when the pupils were on vacation.

So popular was this that a committee was set up and chaired by Dr Edward Astley (1812-1907) to create an extensive public garden also on the Castle slopes. The committee included John Finnis and Henry Hayward – both of whom contributed £500 each – Mr & Mrs Robert Chignell, Steriker Finnis, Richard Dickeson, John L Bradley, William Adcock, Thomas E Back, the Misses Haddon, James Stilwell, Dr Sutton, Alfred Leney, Mrs John Birmingham, W Rutley Mowll and Messrs Hills and Sons of Castle Street. All of whom contributed £100 each.

The committee approached the Department of Woods and Forests to lease, for 99 years, 30 acres of Castle Farm and part of the agreement was that the land was not to be given over to building development. William Crundall gave a piece of land at the top of what became Park Avenue on which the park entrance was created. He also gave a flagpole to be erected at the side of the entrance. A public subscription was set up and £2,700 was quickly raised for fencing, planting and landscaping of the site. The only charge on the council rates was for maintenance, this was agreed to be in perpetuity and a section of the site was set aside as a nursery. Robert Chignell designed the lay out of the park and the construction was under the supervision of Edward May.

Connaught Park Lake c 1900 with the Astley drinking fountain at the front and the whale jawbones just beyond the pond. Martin Jacollette photographer. Dover Library

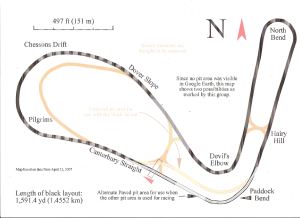

After the creation of the terraces, walks were laid with the intention that the pedestrian could walk from Charlton to the Castle entrance opposite the Constable’s Tower and along the way have extensive views of the sea, harbour and Western Heights. A miniature lake was formed with a fountain in the middle. Nearby a stone drinking fountain was placed that had been bought by Dr Astley and there were ample boarders for flowers. The nursery had a modern hot house where plants could be grown or bought in and kept for planting out to ensure that the flowerbeds would look beautiful from early spring to late autumn. During the winter, appropriate bushes would fill the beds and during the Christmas season be dressed with seasonal garlands.

Edward May was appointed park keeper with a newly built residence adjacent to the park gates. Finally, to make access easier the public roads to the park were widened and improved at a cost of £200.19shillings. By 1882 part of the new park was open to the public and proved more popular than the committee had dared hoped. The whole enterprise was completed by 1 May 1883 when Dr Astley, on behalf of the Park Committee handed over the key to the park to Mayor Richard Dickeson on behalf of the town.

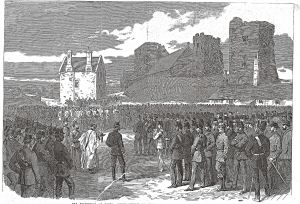

This was not the official opening of the park, that event occurred with great pomp and ceremony on 14 July that year by the Duke and Duchess of Connaught. Prince Arthur – the Duke of Connaught, had been stationed in Dover and was a frequent visitor and he had been invited to open Connaught Hall. However, the town was so proud of the new park that the Duchess was asked to officially open the Park. Following the couple’s arrival at the Town Station they were escorted by the cavalry from the barracks, preceeded by a procession of sixteen carriages containing distinguished visitors and dignitaries. They travelled along Snargate Street to Market Square as originally planned, but instead of then going to the Town Hall, the procession turned into Castle Street went along Maison Dieu Road, up Park Avenue across Love Lane – as Connaught Road was then called – to the new Park. The route was elaborately decorated and at intervals, there were triumphal arches. All the way there were cheering crowds.

Connaught Park – Evergreen Oak planted by the Duchess of Connaught to mark the official opening 14 July 1883. AS 2013

Inside the Park, on the steep banks, were children from St Andrew’s school – Buckland, SS Peter & Paul school – Charlton, St Bartholomew’s school – Tower Hamlets and the Union school at the Workhouse. The children welcomed the Royal couple with a song then watched as the Duchess planted a tree using a silver spade presented by the ladies of Dover. The evergreen oak is still there close to the lake and the inscription nearby was later erected. The Artillery Volunteers, under the command of Captain Poole, provided a guard of honour and the Royal Artillery Band provided the music. When the ceremony was completed the children again sang and to their delight, the Duchess insisted on listening to the end before she waved then goodbye.

Following the formal opening of Connaught Park the procession wended its way down Park Avenue, still thronged with cheering crowds, along Park Street to the Town Hall. There, local women scattered fresh flowers in front of the Duchess, as she climbed the steps. Then the royal couple, together with 450 guests – many of them leading inhabitants of the town – enjoyed a grand luncheon followed by the Duke of Connaught declaring the Town Hall open. Mayor Dickeson paid most of the expenses for which he was later knighted.

Connaught Park quickly proved to be an asset to the town as it was popular with both the townsfolk and tourists. Two years after the opening, William Tourney Tourney – the eccentric owner of Brockhill estate, Hythe – presented the town with the jawbones of a large whale. These were later erected in the Park where they remained until 1967, when the arch was declared unsafe. When the council first announced the intention to remove the jaw bones there was a public outcry. Then one night, while this was all going on, ‘vandals’ came to the council’s aid and cut the jaw bones down for them!

The year after the whale jawbones were given to the town, 1886, while William Adcock was Mayor, there was a national economic depression. To provide work for the unemployed Mayor Adcock paid for what had been the zig-zag part of the old road to the Castle, at the top of Laureston Place to be made into pleasant walkway and diverted to come out opposite the top gate to Connaught Park. The area was terraced and the path lined with bushes making what became a popular with tourists staying near the Seafront. Some twenty years later, when the Admiralty Harbour was almost completed and unemployment in Dover reached new heights, the out of work were employed by the council to dig out part of the hillside at Connaught Park. This was for additional tennis courts. The national coal strike in the spring of 1912 increased the unemployment and relief works included the creation of a croquet lawn at the park.

Connaught Park, during the interwar years became nationally famous for its splendid flowerbeds, lawns, shrubbery’s, promenades and celebrations. On Easter weekend 1919, following the end of World War I (1914-1918), 6,500 children were entertained and given a splendid tea by the Dover Peace Celebrations Committee. This was paid for by the council. In 1922 Sir William Crundall was appointed the Deputy Lieutenant of Kent and shortly afterwards, for his 74th birthday, he gave a garden party at Connaught Park for 7000 Dover school children. To each one he gave an autograph letter saying ‘I was born and brought up in Dover and started work at 14 years and worked for 10hours a day for £5 per year…’ On holiday weekends, during the summer, there was entertainment paid for by the council. For instance, on the 1925 August Bank Holiday the Queen’s Royal Regiment band gave several performances and there was a fireworks display organised by J S Pain and Sons Ltd. In total approximately 8,500 people attended with a further 4,000 going to the park on the Monday evening just to see the fireworks display.

Connaught Park Golden Jubilee 12.07.1933 Mayoress Mrs Morecroft planting a commeration tree. Dover Museum

Towards the end of the 1920s the park became the breeding home of a flock of albino blackbirds. Even today blackbirds, with at least a few white feathers, are fairly common in the area including this author’s garden. During the economic depression of the 1930s, work was provided by the council to lay a car park and build the children’s play area at the park. Money was also found to commemorate the golden jubilee of the opening of the park on 12 July 1933, with the Mayoress, Mrs Morecroft, planting a tree and followed by grand fete. Four years later, in 1937, the Mayoress, Mrs Rosetta Norman, planting another tree in the park, celebrated the coronation of George VI (1936-1952). However, in 1938 as preparation for war a trench shelter for 423 people near the children’s playground was built. The order was then rescinded and demolished but in 1939 it was rebuilt.

World War II was declared on 3 September 1939 and on Friday 21 September 1940, during the Battle of Britain, yet another volley of shells hit the town. The last one exploded in Connaught Park at 16.43hours killing an Army Captain and injuring a number of civilians. On 14 November, the Park was bombed but there were no reported casualties. However, shelling in the afternoon of Saturday 26 April 1941 did cause casualties. Throughout the War the needs of the Park were neglected.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 17 &24 April 2014