Dover Sea Cadets Market Square summer 2013

The training of young men in the art of seamanship was recognised in Denmark 1801 by the establishment of the Academy of Sea-Cadets and the idea soon spread throughout Europe’s maritime nations. Eventually national naval colleges were founded such as the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth and in 1712 the Royal Hospital School was established at Greenwich – it is now located at Holbrook, Suffolk. The original purpose of the school was to provide assistance and education to orphans of seafarers in the Royal and Merchant Navies and eventually it became the largest school for navigation and seamanship in the country.

Sailors’ Home, Blenheim Square. Dover Library

In the seaport town of Dover by March 1846, a Captain Porter of Longford, Ireland, owned St John’s Church, Middle Row. This was in the maritime Pier District of the town. He rented the building to Reverend William Yate, a Church of England clergyman (1803-1877) who enlarged it to accommodate 700 communicants, most of whom were seafarers and their families. It was through his ministry that Reverend Yate saw, at first hand, many problems that destitute seamen faced especially when ships were lost in the Channel. He felt that there was a need for hostel in Dover specifically to meet their needs and through Rev Yate’s tenacity, Dover’s first Sailors’ Home was officially opened on 2 January 1853. This was under the auspices of the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society. John Gilbert (c1812-1890) was appointed superintendent.

John Gilbert founder of the Dover Sea Scouts later to become the Dover Sea Cadets

At the time the first part of the Admiralty backed Dover’s Harbour of Refuge was being built – the Admiralty Pier. Officials included Edward Royds Rice, Dover’s MP, who had fought hard for the Harbour of Refuge and was interested in the work of Reverend Yate and John Gilbert doing everything in his power to help them. Within two years of arriving in Dover, John Gilbert had gathered together the sons of the seafarers in the town and formed Dover Sea Scouts. The boys were required to have two pre-requisites, an interest in playing music – even if the instrument was a comb! More importantly, an active interest in learning seamanship both theory and practice. As time passed, for formal occasions they were provided with smart square rig uniform of navy blue top and white trousers that were paid for out of public subscription – collection tins were positioned at strategic places – and by members of the Rice family.

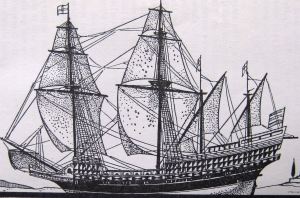

The age of the boys ranged from 8-years to late teens and many stayed on to help with the teaching. Initially Richard Dana’s Seaman’s Friend (published 1841) was the main reference textbook but this was superseded by Lieutenant George S Nares’ Seamanship, first published in 1862. Seamanship training ranged from knowing the principal parts of a ship, rigging and managing sails to helming, making sail and nautical emergencies. The boys would be given practical training initially on local fishing vessels and, as they advanced, hoys and other carriers going from Dover to London and back.

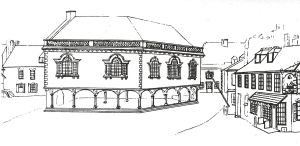

Dover Harbour and the Pier District circa 1830 by Lynn Candace Sencicle

Typically, the hoys would leave Dover at high water, taking the fair tide up to the North Foreland. If conditions were not in their favour, they would anchor off Margate. Otherwise, following two to three hours of adverse ebb, the flood tide would take them comfortably up the Thames estuary to a possible anchorage at Hole Haven off Canvey Island. They would then take the next flood tide to London. With such training, the boys had little difficulty in finding work on fishing boats, cross Channel Packets, ocean going merchant vessels and the Royal Navy.

Lieutenant George Life-Kite from land from Lt G S Nares’ book Seamanship 1862

A few exceptional boys were admitted to the School Frigate Conway, based at Liverpool where they received training to become officers in the merchant navy. That course lasted three years and in 1862 cost 35guineas per annum. To be accepted the boy required a good knowledge of seamanship, leadership abilities and were expected to be literate. The course was run by Liverpool ship owners and following completion of the training, the boy would be accepted as ship apprentices without premiums. In Dover, packet owner Joseph Churchward introduced a similar scheme at a much lower cost to the student.

By 1875, in Germany young men, who had been at sea for three years on merchant ships and having undergone similar training to that Churchward had introduced, were being offered places in naval officer training colleges. The only proviso was passing the entrance examination. Pressure was put on the Admiralty for a similar scheme and this was introduced in 1889. That year, the Naval Defence Act embodied the need for both the Royal and Merchant Navies to be kept strong in order to ward off any possible rivals to Britain’s leading maritime world position.

Western Docks 1920s before Promenade Pier was dismantled. Dover Library

In the mid-19th century at an orphanage in Whitstable, on the North Kent coast, nautical skills were taught. Other orphanages, notably in Whitby, Brixham and Deptford followed suit and from these roots, the Naval Lads Brigade developed. Over the years, similar Brigades could be found in many towns and on 25 June 1899 Queen Victoria presented £10 to the Windsor Naval Lads’ Brigade for the purchase of uniforms. Following a meeting in London, on 11 December 1894, the British Navy League was formed. The first President was Admiral of the Fleet, Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby and among their various objectives was, under the 1889 Act, to promote the Navy to the young through education. By 1910 the British Navy League were sponsoring a small number of Naval Lads’ Brigades.

Up to the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) in Dover the Sea Scouts continued to be a popular avenue in seamanship training and this was recognised by the Royal Navy. Indeed, recruitment from Dover Sea Scouts for ratings was one of the highest in the country. At the same time, the Windsor Branch of the Navy League was developing the skills of their local Lads’ Brigade to a high level. They suggested that the Brigades throughout the country should all receive similar training and come under the auspices of the Admiralty. On 14 January 1919, official recognition was given to the Lads’ Brigades and they were renamed Sea Cadet Corps (SCC). The following year the Admiral of the Training Services took responsibility of the SCC.

Dover Sea Cadet today at Sea. TS Lynx

In many seafaring towns there were Sea Scout groups that had been in existence since the 19th century and in Dover they were faced with two problems. The first was due to the economic depression and the decline of both fishing and small coastal vessels industries. The first was due to the economic depression and the decline of both fishing and small coastal vessels industries. This made the provision of basic seagoing training increasingly difficult but local, Sydney Sharp came to the rescue. He provided an old 27ft whaler, Stormcock, for which he paid £5. At about the same time, the British Sailors’ Society offered a residential year long training course in seamanship for the Sea Scouts. Although competition was fierce, boys from Dover out numbered those from other seaports and on graduation, most joined the Merchant Navy. In 1924, the school was given Royal recognition when Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) gave 20 guineas (£21) for Christmas festivities!

Dover Sea Cadets Sailing today. TS Lynx

The second problem stemmed from 1907, when Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941) founded the Scout movement. As the Boy Scout movement’s popularity increased so did confusion with the Sea Scout movement. This gave the impetuous to a number of Sea Scout groups applying to the Admiralty to be part of the Sea Cadet Corps and this included Dover. Following an inspection by Captain C.H. Pilcher on 7 June 1926 the Admiralty officially recognised the Dover Sea Scouts as Sea Cadets. By this time, not only were members from the maritime families of Dover but from other walks-of-life. This was brought home to the people of the town that year by the death of James Joseph Smith, who was killed while working down Snowdown pit. While the Unit escorted James’ coffin through Dover shop owners drew their blinds and folk turned out to show their respect.

The previous year, 1925, the Seaman’s Mission amalgamated with the National Sailors’ Society and the lease of their Northampton Street premises was put up for sale. The Sea Cadets managed to raise £1,600 and bought it. However, their tenure was short lived for Dover Harbour Board (DHB), who owned the freehold, used a compulsory purchase order to take over the building and it was demolished in 1930. The Cadets were offered the use of the Drill Hall in what was Liverpool Street. In 1937, Lord Nuffield gave £50,000 to fund the national expansion of the Corps and by the start of World War II (1939-1945), there were nearly 100 Units with some 10,000 cadets. However, in Dover, the Drill Hall was requisitioned for military purposes.

HMS Lynx Minesweeping & Patrol Base St James Lane plaque unveiled June 1984

The Dover Sea Cadets moved first to River Primary School then to the River Parish Hall followed, amongst other places, Crabble Athletic Ground. On 1 June 1940 more than 3,000 children were evacuated from Dover to Monmouthshire, Wales but by September some 800 had returned and the numbers continued to increase. During this time George VI became Admiral of the SCC and in Dover the Minesweeping and Patrol craft headquarters, H.M.S. Lynx, operated from the cellar of the former bus garage in St James Lane. To meet the needs of the older children who had returned to the town, from 1941 to 1943, Commander William Gillette, the minesweeper maintenance officer took special interest in promoting Sea Cadets in Dover.

In January 1942, the Admiral Commanding Reserves took over the training of the SCC but in Parliament, it was stated that there were only 13,000 SCC and so to coincide with War Ship Weeks, there would be a recruitment drive to increase the number to 50,000. War Ship Weeks were held in every town and village when emphasis was given to the Navy and the locality would adopt a named ship for which they would make a collection. It was also agreed that to help recruitment to the SCC, the Admiralty would pay for uniforms and the Navy League fund sport and unit headquarters.

Sea Cadets Market Square c 1947-8. Courtesy of TS Lynx.

That same year saw the formation of the Girls’ Naval Training Corps as part of the National Association of Training Corps for Girls. Other changes included the introduction of Units numbers in sequence to their affiliated to the Navy League and an order was sent that new recruits had to be at least 14½ years old and of 5feet 2inches (1m 57.5cms) tall! Under the Ministry of War Transport scheme, in 1944, all Sea Cadets having reached the age of 16½years and suitably qualified could obtain quick entry into the Merchant Navy. They were required to pass out of a four weeks’ course at the Wallasey Sea Training School on the Wirral.

Dover Sea Cadets 1949. Courtesy of TS Lynx.

In 1947, both Admiralty and the Navy League agreed a continuation of their wartime co-sponsorship and this was embodied in what tends to be called the Sea Cadet Charter. It was agreed that the Admiralty would support a maximum of 22,000 cadets by supplying uniforms, boats, training facilities, travel expenses and limited pay to adult staff with retained appointments in what is now known as the Royal Naval Reserve, (RNR). The Sea Cadet Council was set up to govern the SCC and a retired Captain took on the supervision.

Kings Hall, London Road for about 15 years TS Lynx

As a mark of esteem for the large contingent of Dover Sea Cadets, in July 1949 the Ladies of the Dover Society presented them with their colours. At about the same time Dover Sea Cadets moved into the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on Buckland Terrace, off London Road (now the King’s Hall). In May 1955, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Oliver (1898-1980), Commander in Chief, officially dedicated the Dover Sea Cadet Unit as Training Ship Lynx after the wartime connection between the Minesweeping and Patrol craft headquarters and the Dover Sea Cadets. The Cadets were again presented with new Colours. That year saw the formation of the Marine Cadet section of the SCC.

Trawler and Minesweeping Patrol Memorial 1914-1918. Originally in the Holy Trinity Church- Pier District then Archcliffe Fort now Dover Museum. Dover Museum

In the late 1950s, the name of the Girls’ organisation was changed to the Girls’ Nautical Training Corps and in 1964, they were formerly affiliated to the SCC. However, at local level, the Wesleyan Chapel was put up for sale and the Dover SCC was forced to look for a new home. The Army, at the time, was occupying Archcliffe Fort and found them space. Fittingly, on the wall of their new headquarters was the memorial to the World War I Dover Trawler and Minesweeping Patrol (now in Dover Museum).

Then, in 1978, Archcliffe Fort was taken over by English Heritage and the Sea Cadets were homeless again. At the time, the Chairman of the Dover SCC was Cllr. Walter Robertson and he approached Brigadier Maurice Atherton, then deputy-Constable of Dover Castle and now President of the Dover Society. The Brigadier persuaded the Department of the Environment to allow the SCC to use the old Garrison primary school near the Castle. The building had stood empty for 15 years and was in a poor state but over the next few years, the Dover SCC managed to raise enough money and refurbish the building.

At the national level in 1976, the Navy League was renamed the Sea Cadet Association and the Admiralty responsibility for the SCC, was transferred to the Commander-in-Chief Naval Home Command in Portsmouth. The Sea Cadet Charter was revised and replaced by a Memorandum of Agreement. On 31 March 1980, the Ministry of Defence (Navy) approved the admission of girls into the SCC.

Countess of Guilford opening the new Training Ship Lynx, accompanied by Lt Dick Liggett. September 1983

In June 1982, Rear Admiral George Brewer unveiled the plaque on the wall of the former East Kent Road Car Company’s Bus garage, at the time owned by East Kent Bus Company, in St James Lane to commemorate all the Officers and Ratings Minesweeping and Patrol craft that served in HMS Lynx during World War II. The Dover SCC provided the honorary guard. The following year Lady Guilford officially opened Training Ship Lynx at the old Garrison school. Alterations had cost £4,500, included redecoration and had been undertaken by workers under the Manpower Services Commission’s Youth Opportunities Programme, supervised by Dick Horton. During ceremony a special presentation of a Unit Ceremonial Sword, that had belonged to the late Commander William Gillett, of HMS Lynx at Dover, February 1941 – June 1943. Lieutenant Eley, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve made the presentation to Lieutenant Dick Leggett and the Cadets on behalf of Commander Gillett’s daughters

Dover Sea Cadets 1985. Courtesy of TS Lynx.

Richard Liggett Lt. Cdr. (SCC), in 1986, formed a Unit for Dover girls and in 1992 Sub Lt. (SCC) David Kemp, Officer-in-Charge, T.S Lynx, formed the Dover Junior Section. That year single sex units were abandoned and cadets were amalgamated into mixed sex units. Two years later the Parents and Supporters Association was set up. Since that time the Dover Sea Cadets have gone from strength to strength, undertaking sea training on H.M.S. Illustrious,s community activities and Petty Officer Cadet Craig Clark and Leading Cadet Tim Weaver, were appointed the Lord Warden’s Sea Cadets at Admiral Ls Installation in Dover on Tuesday 12 April 2005.

Dover Sea Cadets Sailing. Courtesy of TS Lynx.

It looked as if the Dover Sea Cadets were going to loose their premises in the old Garrison schoolhouse behind the Castle when, in 2008, the Ministry of Defence put the premises up for sale. The £30,000 was raised and the premises were bought – at last, after more that 160-years the Dover Sea Cadets had a permanent home! 2013 was an eventful year for the Dover unit. Eileen Wiggins became the Honorary Patron – in respect and gratitude for her underlying loyalty, love of her family (former sea cadets) and the Dover Sea Cadets. The Dover SCC was awarded the Burgee Award for the second time. This is the Highest Award the Headquarters can give to a unit and is given for the effectiveness of training. Finally, due to the increasing size of the catchment area, in 2013 the group changed their name to the Dover and Deal Sea Cadets.

Dover and Deal Sea Cadets 2013. TS Lynx

It is now March 2014 and already the unit has been nominated for the National Sea Cadet Award – TS Indefatigable Cup – for the most improved unit in the Southern Area, which are 80 units strong.

Former Dover Sea Cadet, Sarah Butler, is the present Commanding Officer, previous ones include: Dick Liggett, Dave Kemp, Peter Franklin and from 2002 to 2012 Sheila Watson.

Contact:

info@tslynx.co.uk

facebook.com/doverseacadets

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 15, 22 & 29 May 2014