From the days before the Conquest (1066) and for centuries after, Dover, as a Cinque Port, had a number of privileges in return for providing ship-service to the ruling monarch. These privileges included the full authority to deal with all criminal offences and the right to arrest, imprison or execute criminals. The mayor passed all sentences, including those of death and the last time was in 1823.

Execution was, for centuries, carried out by throwing the guilty felon from the Bredenstone on the Western Heights. If they survived they could walk or be carried away otherwise they were buried in unconsecrated ground. It was for this reason that the Bredenstone – the western Roman Pharos, was nicknamed the ‘Devils Drop of Mortar.’ With the development of the Pier District, below Western Heights, the execution site was moved to the top of Sharpness (now Shakespeare) Cliff giving it the nickname ‘Devil’s Drop!’

Public hanging increasingly became the preferred punishment as people could watch and, it was argued, this was a greater deterrent. Wooden gallows became a permanent fixture and were only replaced when dilapidated or when the incoming mayor wanted to make a point. Thomas Warren, elected Mayor five times from September 1549, had strong views on punishment as a deterrent so during his administration the gallows were replaced, the ducking stool was repaired and a new lock for the stocks was ordered.

Plaque erected by the Dover Society on the Eagle Hotel, Tower Hamlets opposite to where the gallows once stood.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, public hangings were a common occurrence in Dover and took place outside the ancient boundary on the corner of the High Street and Tower Hamlets Road. Today there is a Dover Society plaque on the Eagle pub opposite to where the gallows once stood on the corner of Tower Hamlets Road. The last Dovorian to be hanged there was Alexander John Spence who had been found guilty of shooting Lieutenant Philip Graham. Graham was a Preventative Coastal Blockade Officer working from the ship Ramillies based at Dover. It was during a confrontation with a group of smugglers that Spence shot at Lieutenant Graham.

Spence was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging under the Malicious Shooting and Stabbing Act. Lord Ellenborough, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales had proposed the Bill, in order to clarify the law relating to abortion. As the Bill wended its way through Parliament it was used to clarify other offences including shooting at an officer during the course of his duties. The Act was given Royal Assent on 24 June 1803 (43 Geo 3 c58).

The prison, at that time was in Gaol Lane, off Market Square, and on the morning of Spence’s execution, 9 August 1822, he ate a ‘hearty breakfast.’ Then he was seen by Reverend John Maule of St Mary’s Church who tried to impress upon Spence his miserable situation but the condemned man remained resolute. Later one of Spence’s sisters visited and his attitude change. He asked for the sacrament and at the time to leave the gaol he dutifully climbed into the cart that was to take him to the gallows.

The cart, with horse and driver, to carry the condemned man was hired from Worthington’s stables in what was then Worthington Lane, (now Street). Mr Worthington charged 10s (50p) of which 2s 6d (12½p) was paid to the driver. Spence sat on his coffin in the body of the cart. Rev. Maule stood by him constantly praying. The executioner, carrying the rope, sat at the front with the driver. The Mayor, Henshaw Latham, and town dignitaries travelled in covered carriages behind.

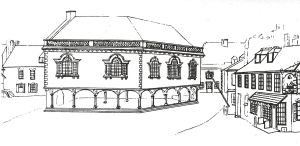

The spectacle of the condemned man being taken along Biggin Street and then up the Charlton High Road (now High Street) in an open cart to Black Horse Lane – the old name for Tower Hamlets Road – was enjoyed by the ‘multitudous’ crowd. Rooms with windows at the Black Horse Inn – now rebuilt as rename the Eagle – were hired for £1.1s (£1.5p), by the town’s wealthy. They were, apparently, enjoying light refreshments when Mayor Latham and the other officials joined them.

On his way to the gallows Spence remained standing, waving to the crowds and bowing to his friends and relatives as he passed by. Standing by the gallows was Preventative Officer Lieutenant Graham and his colleagues and when Spence saw them he became meditative. The hangman swung the rope over the gallows and then joined Spence and the Rev Maule in the body of the cart. He put the hood over Spence’s head and then the noose but before the executioner could drive the cart away, Spence either slipped or threw himself off and ‘struggled wildly.’ Afterwards, Spence’s body was given to relatives for disposal and he was buried in St Mary’s Churchyard.

The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 took most of the ancient privileges away from the town’s officials including the right of passing the death sentence. Although Alexander Spence was the last Dovorian to be publicly hanged on the town’s gallows, in 1823 a young man from Margate was hung there for robbery. In August 1868, Dovorian Thomas Wells, a 19-year-old London, Chatham and Dover Railway carriage cleaner was hung at Maidstone Prison. He was the first person to be convicted of murder following the enactment of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act of 1868 that put an end to public executions. In the UK, execution was abolished (except for treason) in 1973, the last one took place in 1964 and the punishment was abolished totally in 1998.

As for the Preventative Coastal Blockade Officer, Lieutenant Philip Graham of the Ramillies, whom Spence had been convicted of shooting. At the Lent Assizes, Maidstone in 1826, Graham was convicted, with costs, of ‘sending challenges’ to Robert Sherard, 6th Earl of Harborough (1797–1859), ‘with the intent to provoke him into fighting a duel.’

One afternoon the Earl arrived in Dover Bay on his yacht that he moored on Dover’s Archcliffe Beach (now part of Shakespeare Beach). This was the usual place for smugglers to tie up. Lieutenant Graham and his officers, in their official capacity went onboard and conducted a search. The Earl was dressed like a common seaman and, by his own admission, used strong and course language and told them to leave. An altercation took place during which, the Earl alleged, Lieutenant Graham gave him his calling card saying that ‘he expected the satisfaction of a gentleman.’ The Earl tore the card up and threw it to the crowd of onlookers who cheered. Lt Graham then ordered the Earl to take his yacht round on the next high tide to the Custom shed, on Customs House Quay. The Preventative officers then left.

The Earl did as he was bid and the yacht was again searched, nothing was found. However, in the Customs house, according to John Ward – Collector of Customs, Lieutenant Graham told him that he had laid a challenge and that the Earl was a coward for refusing it such that he ‘should be under the necessity of kicking him.’ Ward was the only witness to this alleged conversation.

Lieutenant Graham’s colleagues, at the trial, said that during the first examination of the yacht, the Earl was ‘extremely violent,’ accusing them of being ‘highwaymen,’ and tauntingly doubted that Lieutenant Graham had the ‘king’s commission’. The Earl then demanded to see the evidence, to which Lieutenant Graham produced his card that showed who he was. The Earl’s loud and abusive behaviour had attracted the attention of fishermen and known smugglers and taking the card the Earl tore it up and threw to the wind. The Preventative officers decided to examine to yacht later that day and the Earl was ordered to take it round to the Customs house on the next tide.

Of the Lieutenant, his colleagues said that he was a peaceable and brave man, and a humane and skilful officer. This was backed in affidavits by a number of Dover gentlemen including, Thomas Mantell, George Jarvis, Henshaw Latham, Richard Elsam, Henry Pringle Bruyere, William Knocker, John Shipdem and Mayor George Stringer. Lieutenant Graham was represented by the Attorney General and the jury found that though Lord Harborough was not engaged in any smuggling activities, he conducted himself in a manner to give reasonable ground to the officers to suspect that he was in practices of that nature.

However, the jury preferred the Earl’s and Collector of Customs, John Ward’s version of events to that of Lieutenant Graham and his witnesses. The judge, Mr Justice Bayley, in summoning up before sentencing said that ‘officers’ of the Crown ought to behave with temperance and moderation, and that their failure so to behave must be attended with painful and mischievous results.’ He sentenced Lieutenant Graham to four months in Marshlsea prison, London and the loss of his job.

The Coastal Blockade and the Preventative Water Guard – the latter served the rest of the country – amalgamated in 1821 under the Board of Customs, and were renamed the Coast Guard – in the twentieth century this was changed to Coastguard. The Preventative Officers came directly under the Crown and their job was to prevent smuggling. The Customs was effectively privatised under a Collector of Customs for each locality. The Collector of Customs tendered for the privilege and once in post, it was he who hired the customs officers to collect the excise duties on the goods that were being imported or exported. The Collector of Customs received a percentage of these revenues and after paying his staff and renting the customs house etc., he retained what was left as his income.

- Execution published:

- Dover Mercury 05.11.2009