Prelude: London, Chatham & Dover Packet Service 1860-1874

English packets out of Dover, that is ships carrying official messages and mail, evolved over the centuries. By 1624, there was a well-organised service to and from the Continental mainland. In the 1850’s the service, run by the nation’s General Post Office, was partially privatised with contracts that were purchased by private individuals to provide the service for a specified period of time. In 1852, Joseph George Churchward (1818-1890) won the packet contract for the Dover-Calais route (see Packets Part 2 and Part 3) and when the London, Chatham & Dover Railway opened their railway line to Dover in 1860, Churchward still held it.

The London, Chatham & Dover Railway (LCDR) had been set up with the over-riding ambition to create an international freight-forwarding enterprise that co-ordinated the international exports and imports throughout the country. It’s centre was to be a massive depository on the Thames embankment, near to Victoria Railway station(see LCDR part I), from where their train services to Kent and the South East ran. The depository was to have its own wharf and their Continental shipping outlet was to be along the Thames estuary and across the North Sea. A second outlet was to be the port of Dover. To gain access to the port of Dover, LCDR had by-passed the established South Eastern Railway’s (SER) London to Dover rail network via Ashford and Folkestone and opened their route via North Kent and Canterbury.

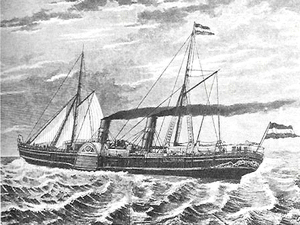

In 1860 the LCDR railway line had reached Dover harbour and on 1 November that year they opened Harbour Station on the western side of the then harbour. In July 1860 they floated the LCDR Steamboat Service, a cross Channel shipping subsidiary company, which was the start of the envisaged freight forwarding enterprise. The Company then bought paddle steamers:

Samphire – a 330gross tonnage iron paddle steamer designed by Lieutenant Edward Edwin Morgan (1815-1892) and built by Messrs Money, Wigram & Co of London in 1861. She had 2×80 horsepower diagonal oscillating engines, with pistons 50inches in diameter with 3feet9inch stroke. These engines were built by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co, Middlesex. Along with the Maid of Kent below, they were the first cross channel ships to have private cabins.

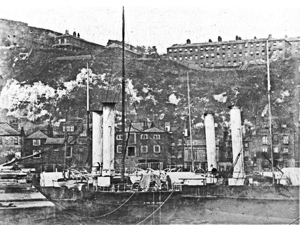

LCDR packet paddle steamers Samphire and Maid of Kent in Western Docks with the Western Heights Barracks on the cliffs behind. Dover Museum

Maid of Kent (1) also designed by Lieutenant Morgan and engined by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co. At 335gross tons, she was slightly bigger than the Samphire and built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar.

Petrel again she was designed by Lieutenant Morgan built by Messrs Money, Wigram & Co of London in 1862. The ship had 2×120 horsepower simple oscillating engines built by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co, Middlesex.

Scud launched in 1862, was an Iron paddle steamer 482gross tonnage. Built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar with 2×120 simple oscillating horsepower engines by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co. She was sold in 1872 and relocated at St John, New Brunswick but on 8 August 1882 was lost off Nova Scotia while on a passage from Boston, USA to Lunenberg, Nova Scotia.

Foam an Iron paddle steamer 497gross tonnage was launched in 1862 and built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar with a bow rudder. Her 2×120 simple oscillating horsepower engines were by Ravenhill, Salkeld & Co.

At this time, operating out of Dover harbour, with the Dover-Calais contract, was the Royal and Imperial Mail Steam Packet Company, owned by Churchward. With partners, he also held the Calais-Dover, Dover-Ostend and the Ostend–Dover contracts. In 1863, the Dover-Calais contract came up for renewal and was to run until 1870. It was expected that Churchward would either retain it or that the much larger SER, which also put in a bid, would run the service.

Operating out of Folkestone Harbour, they had developed, SER held both the Folkestone-Boulogne and the Boulogne-Folkestone packet contracts. Although their railway line from London actually terminated at Dover and from Folkestone to Dover ran through tunnels or at the base of the cliffs along the seashore. The Company’s chairman was the Mancunian, Sir Edward Watkin (1819-1901), who had worked his way up through the senior management structure of a number of railway companies. He was knighted in 1868 for his work in assisting the Canadian Federation and when Watkin was appointed Chairman of the SER in 1866, his wide experience and strong personality dominated. Further, his driving ambition, which he doggedly pursued, was a continuous railway line between Manchester and Paris. Watkin was also a seasoned Member of Parliament (MP) and having won the Hythe seat in 1874, he remaining their MP until 1895.

James Staats Forbes (1823-1904) Chairman of LCDR by George Charles Beresford 1864-1938. Wiki Commons

At the time the contract came up for renewal, LCDR, was already heading for deep financial trouble and in 1864, were forced to sell both Petrel and Foam. However, their General Manager, James Staats Forbes (1823-1904), saw the Company’s future prosperity in shipping rather than freight forwarding and submitted a lower bid than the other two. Forbes was born in Aberdeen to a railwayman and had trained as an engineering draughtsman. He then joined the Great Western Railway (GWR) as a booking office clerk at Paddington Railway station, London. He quickly climbed the lower and middle management ladders to become the goods superintendent and married Ann Bennett (1820-1901). They had five children, the first of which was George (1853-1855) who died at the age of two. The others were the eminent zoologist William Alexander (1855–1883), Ann born circa 1857, Sarah, born 1859 and Duncan Stewart born 1858. The latter went on to work for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway.

Forbes youngest two children were born in the Netherlands, where he had been recruited as the General Manager for the British managed Dutch-Rhenish Railway Company. His contract was for five years – which at the time was not likely as the Company was in a poor financial state. In the event, Forbes, using his natural business acumen, charm, resourcefulness and brilliance as a negotiator, turned the Company round. At the end of the contract Forbes declined to have it renewed but did accept the post of permanent adviser. The remuneration he earned from this sustained the Forbes’ family living standards throughout the hard times with LCDR that were to follow.

At the time of the Dover-Calais contract, Watkin was not the Chairman of SER but as a Board member, he argued for the Company to undercut Forbes bid, but was over-ruled. It would have meant that contract would be financial loss to SER. However, there were those with governmental power who did not want it awarded to Churchward and were apprehensive about it going to LCDR, as that Company had serious financial problems. Indeed, it was implied to SER that if they put in a bid equal to that of LCDR, they would be awarded the contract. This was put to the SER Board but they declined saying that the Folkestone route was the key to the whole Continental traffic while Dover was a mere backwater.

In the event LCDR were awarded the contract and the Company bought Churchward’s shipping stock and associated property. Forbes also negotiated a deal with Churchward whereby LCDR took over all of his contracts. However, as the contracts were in Churchward’s name, he still retained ownership. As the holder of the Dover-Calais contract, LCDR was privy to Berth 2 on the Admiralty Pier, where the London-Dover mail trains terminated. At that time, SER had held the contracts to carry both the Calais and the Ostend mails between London and Dover but by winning the packet contract, LCDR gained the London-Dover, Calais mails contract too.

Of the original fleet of Churchward ships, purchased by LCDR when they gained the contract, by 1875 only the Prince Frederick William of Prussia – usually shortened to Prince Frederick William remained. She was a 215-ton gross iron paddle steamer, designed by James Ash & Co of Poplar, launched in 1857. She was 180feet in length and 20-feet beam, 203-tons gross with 2×75 horsepower engines.

They had, however, in the intervening time purchased the:

Prince Imperial a 327.29gross tonnage iron paddle steamer from James Ash & Co of Poplar. She had, 2×90 horsepower oscillating engines that were supplied by Penn’s of Greenwich.

La France a 388 gross tonnage iron paddle steamer built by James Ash & Co of Poplar. She had 2×90 horsepower ordinary oscillating type engines.

The cost of purchasing and crewing the two ships had added yet further strain to LCDR’s already over-stretched resources but the Dover-Calais packet contract was potentially lucrative. Forbes was confident that the LCDR fleet would soon pay for themselves. However, both the Belgium and the French government had insisted that packet contract senior partners were nationals from their own countries. In the case of the Ostend-Dover contract the ‘senior’ partner was Belgium Marine a subsidiary of Belgium State Railways. Before the LCDR deal with Churchward was signed, Belgium Marine had independently applied to the Belgium government to buy out Churchward’s Ostend-Dover share. They also managed to purchase the Dover-Ostend contract and from then on Belgium Marine held the monopoly of the Dover- Ostend packet route for over a century.

The Continental Agreement that was ratified in 1865 and divided the amount received by SER and LCDR for train journeys on the railway lines between London and the Channel ports.

Not long after LCDR had gained the Dover-Calais packet contract, SER suggested that both Companies would benefit if they created an oligopolistic market. This proposition suited the LCDR Board even though it was readily apparent that the Continental Agreement, as it was called, worked in SER’s favour. They were under financial duress and saw the passage/packet enterprise of short term duration and the Continental Agreement would provide much needed income. In essence, the Agreement meant that the two Companies pooled the profits earned from folk travelling on their railways to and from their cross-Channel ports. Although Forbes was unhappy about the terms he did manage to make modifications and the Agreement was ratified on 10 August 1865. Initially, LCDR received 32% and SER 68% of their joint takings with the gap progressively closing until 1872, from when on the takings were divided equally.

The French Calais-Dover contract, like that of the Belgium contract, was in Churchward’s and his senior national partner’s name. This expired in 1870, three years after the direct rail link between Calais and Boulogne opened, which shortened the route between Calais and Paris. French political changes delayed the renewal until 1873 and, at the same time the Boulogne-Folkestone contract came up for renewal. Initially, both contracts were awarded to a French company but when it collapsed (See part 4 of the Packet story), both British companies were awarded the contracts but with stipulations. One of these, as far as LCDR was concerned, was that the transportation of the midday mails was on ships manned by French crews and flying the French flag. The Prince Imperial, La France, Petrel and Foam were assigned to the midday crossing.

In 1866 LCDR were declared bankrupt, following which Forbes, along with the recently appointed Company Secretary, William E Johnson, became the joint managers and receivers of the Company. The Company was restructured, a new quasi Board of Directors were appointed and major consolidation took place. Although the financially disastrous rail side of the Company’s operations took up much Forbes time, he still took an active interest in what was becoming the most profitable part of LCDR, the Dover packet operations. However, the Samphire accident of 1865, pushed that sector into the red. Forbes, with the backing of a loyal and complying Dover maritime workforce stopped the packet side of the business sliding into further debt.

The final act of the quasi LCDR Board was, in 1873, the abandoning of the international freight forwarding dream and the Company regained its independence. A Board was appointed by the shareholders and the existing Chairman retained his position by a show of hands. He recommended the LCDR should build new railway engines and that Forbes was to be appointed to the Board. This was agreed and Martley ‘Europa’ Class 2-4-0 engines were purchased.

The following year, Forbes was offered the Chairmanship of LCDR, which he recognised was a poisoned chalice. Although, throughout all of LCDR’s turbulent history, Forbes had been awarded a large and increasingly escalating salary, in realty, the remuneration he received had fallen from when he was first employed by LCDR. Thus, much of the family income came from the stipend he received from the Dutch-Rhenish Railway Company. LCDR was broke, it desperately needed new trains, ships and infrastructure. The workforce needed living wages with prospects and there was little hope of the Company making ends meet in the near future. Thus, Forbes accepted the position but only on a temporary basis.

London Chatham and Dover Packet Service 1875 – 1884

Not long after Forbes became Chairman of LCDR he became seriously ill and was totally debilitated throughout the winter of 1874-75. During that time Watkin, on behalf of SER, proposed a quasi merger between the two Kent railway/packet companies. In essence, Watkin suggested, there would be a fusion of the net profits of both companies, for an interchange of traffic and a friendly working relationship. The notion sounded good and the LCDR Board, agreed to a meeting. There, it was pointed out, by Watkin, that SER’s fleet of paddle steamers besides the Princess Maud and the Princess Clementine, which they had occasionally placed at Dover, consisted of five modern paddle steamers. These were the Victoria and Albert Edward, both of which could make the crossing from Folkestone to Boulogne in 1½ hours while the newer ships, Alexander, Eugene and Napoleon III were at the forefront of modern paddle steamer design. The LCDR Board were impressed and a series of amalgamation meetings were arranged for when Forbes returned to work.

The meetings were held in early March 1875 and Watkin expanded on the finer points of the deal and detailed the bureaucratic hurdles that had to be surmounted. The final one of which was parliamentary approval. Nonetheless, Watkin added, in the meantime the two Companies could take the proposed course of action on a provisional basis. The LCDR Board were in full agreement but Forbes was not so enthusiastic. He pointed out that the proposals were a broader version of the Continental Agreement that would be applicable to all the LCDR operations not just cross Channel traffic. Further the five paddle steamers that had been implied as relatively new, was open to interpretation. The Victoria and the Albert Edward were built in 1860 and 1861 respectively, while the Alexander and Eugene were built in 1864 and the Napoleon III was built long before the Emperor abdicated in 1870!

The LCDR Board agreed with Forbes that clauses were to be inserted into any agreement that protected the LCDR rail and maritime service along with LCDR staff, before asking for shareholders acceptance. Watkin, however rejected Forbes proposition and refused any compromise. At the end of May 1875, Forbes issued a formal statement saying, in effect, that negotiations had broken down but that LCDR were willing to reopen discussions.

Site of the present day Pencester Gardens drawn in 1831 by George Jarvis, bought by SER in 1880 for a grand central Dover railway station for Watkin’s Channel Tunnel project.

Unperturbed, Watkin turned his attention to his primary objective, that of a continuous railway route between Manchester and Paris. Back in 1872, the SER shareholders voted £20,000 to build a Channel Tunnel. At the time, the project was to be undertaken in conjunction with the French Nord Railway. To this end, SER formed the Submarine Continental Railway Company and excavation was started at Abbots Cliff when a 74-foot shaft was sunk and a level heading was driven 2,601-feet. A French team undertook borings at their side of the Channel at Sangatte. A second 44-foot shaft was then sunk at the foot of Shakespeare Cliff in February 1881 and the heading progressed 6,380-feet under the sea. Work was going so well that Watkin bought Pencester Meadow, with the view of building a large, luxurious railway station in the centre of Dover. In 1878, SER installed a 60-lever signal box (Hawkesbury Street Junction) adjacent to the Town Station in preparation for the new railway line. However, at parliamentary level the Joint Committee of both Houses were of the opinion that a Channel Tunnel would not be expedient and the project was forced to be abandoned.

The Pencester site was put on the market and bought by William Crundall senior (1822-1888) and eventually became the Pencester Gardens we see today. These days the site adjacent to what was the Watkin Channel Tunnel boring plus the spoil from the present Channel Tunnel was levelled to create Samphire Hoe. This is run by the White Cliffs Countryside Partnership (WCCP) and is a popular visitor attraction. As for Watkin’s Manchester-Paris railway line ambition, this never materialised. However, in 1886 Watkin received a report from Professor Sir William Boyd Dawkins (1837-1929), an eminent geologist who was the main adviser to the Submarine Continental Railway Company. By that time Dawkins was boring for evidence of coal seams in the neighbourhood of Dover. His findings led to the discovery of the Kent Coalfield and the sinking of the long closed Shakespeare Colliery.

Forbes watched Watkin’s Channel Tunnel endeavours with interest but making LCDR pay was uppermost in his mind. The packet side of the business dominated discussions in the prominent national newspapers, particularly in relation to the major scourge of seasickness. The then famous inventor/engineer Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) had adapted a design of a paddle steamer by Sir Edward James Reed (1830-1906) that, it was reported, provided the answer to this problem. Reed had changed the way ships were designed from ‘the rule of thumb’ to calculations based, he said, on sound theoretically principles and from careful experiment he had produced a model that was internally stable on all occasions. Bessemer had adapted the Reed design and a ship had been built with a special swinging saloon, located along the centre of the ship, which rested on two telescopic cylinders with pistons. This kept the floor of the saloon horizontal, it was said, even during the roughest of crossings and Earle’s Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Hull had built the prototype for Bessemer.

The prototype ship was named Bessemer, tonnage 1,974gross. She was 350feet in length and 65feet across the paddle boxes with a draft of 7feet 5inches. She was driven by 4 paddle wheels, two on each side that were powered by four sets of simple oscillating engines placed fore and aft to be out of the way of the saloon. The internal dimensions of the saloon were 70feet long, 30feet wide with a height of 20feet. Besides the main room, the rest of the saloon area was divided into a number of smaller rooms. The saloon area had spiral columns of carved oak and gilt moulded panels. Hand-painted murals decorated the walls while the seating was of Moroccan leather.

Forbes arranged for the Bessemer to be brought from Hull to Dover by LCDR’s Captain James John Pittock (1827-1899) at the beginning of March 1875. This was for a trial purpose only as he did not make any promises to purchase the ship. During the journey, Pittock and the crew tried out the anti-sea sickness mechanism. This was designed to keep the saloon steady by hydraulic machinery that oscillated by means of a mechanism called a ‘manipulator’. A member of the crew, using two short handles one in each hand, operated this by moving them in accordance with the movement of the ship. The sea condition, using the Beaufort Wind Scale when these trials took place were 4-5 fresh to strong breeze, small to moderate long form waves with white horses. Pittock reported that the manipulator worked. At the beginning of May, with members of the LCDR Board, Forbes crossed to Calais on the Bessemer. The weather was fine (Beaufort scale 2-3) and she made the crossing in 1hour 40minutes and equivalent for the return journey.

It was agreed that the Company would hire the Bessemer for the Whitsuntide holidays of Monday 17 and Tuesday 18 May. Special excursion trains were laid on and adverts placed quoting the fare as 5shillings a head with refreshments on board. A week before the special excursions, 500 gentlemen, including Prince Albert the Duke of Edinburgh (1844-1900) and the Lord Warden and Chairman of Dover Harbour Board (1866-1891), George Leveson Gower the Earl Granville (1815-1891), were the guests of LCDR. They crossed, on the Bessemer on a calm day to Calais and were then taken by the Northern Railways of France Company, to Paris for the weekend.

The Whitsuntide excursions proved a sell out and the ship was full on the first crossing to Calais. However, a few days before, on entering Calais harbour under Captain Pittock, the Bessemer caught a portion of the West Pier and demolished it. Surveyors for LCDR reported that both the wooden piers facing the entrance of Calais harbour were rotten and Sir Edward Reed endorsed this. Nonetheless, LCDR were sent a bill for £3,000 for repairs, which was more than LCDR would earn from the special excursions. As for the excursions, the weather did its worse with wind speeds increasing from force 6 on the Beaufort Scale to gale force 8 by the end of second day. The crew members operating the manipulator found it impossible to keep up with the ship’s movements and Captain Pittock ordered it to be closed down. Afterwards, he also reported that in the rough weather, the Bessemer was sluggish in answering the helm and was difficult to manage due to where the engines were situated.

LCDR declined offers to hire Bessemer again and in March 1876, following liquidation of the Bessemer Saloon Steamboat Company Ltd, she was at Millwall Docks on offer for sale by auction. This was held at the Captains’ Room of Lloyds Insurance, London in what is now the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Forbes, who attended, reported that she failed to obtain a bid and eventually the Bessemer was sold. The swinging saloon was removed before she was scrapped in 1877 and Reed purchased it for a billiard room at his home at Hextable, Kent. When the House eventually became part of a college, the saloon became the dining room. During World War II (1939-1945) the building was bombed and subsequently demolished including the unique dining room.

On 15 September 1875 another ship designed to combat the mal de mer made her maiden voyage from Dover to Calais. She was the Castalia made up of two hulls joined with strong girders and covered with a wide upper deck (see Packets IV last paragraph). LCDR hired the ship and she not only lived up to expectation but proved popular. In 1876 she carried over 10,000 passengers during the summer months. The free publicity provided by national newspaper articles, for both the Bessemer and the Castalia brought about an increased interest in crossing the Channel to Calais. And subsequently the number of people using the LCDR trains to and from Dover and on the LCDR packet ships also increased. By the end of the year Forbes reported that 209,133 passengers had made the crossings, which was more than double the number of passengers in 1870 (102,673). Further, he added, LCDR had carried almost twice as many passengers than those carried by SER between Folkestone and Boulogne!

Besides Prince Albert the Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s (1819-1901) extensive family were also regular passengers on the LCDR ships. They were all treated with the utmost courtesy and all their comfort needs were dealt with in the best way possible, including sea-sickness. In October 1875 Edward the Prince of Wales (1841-1910) and his wife Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844-1925), along with the Duke of Edinburgh, embarked on the Castalia with Captain Pittock in charge. The Prince went on to Paris while the Princess and the Duke returned to England on the Castalia.

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1850-1942) regularly made the crossing as part of his military duties. These included travelling on the Castalia as well as the LCDR packet ships. In June 1873, the Duke brought his intended bride, the 13 year old Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia (1860-1917) to Britain on the Maid of Kent under the command of Captain William Waller Paine (1844-1917), to meet his family. She was the daughter of Prince Frederick Charles (1828-1885) and a great-niece of Emperor Wilhelm I (1871-1888) of Germany, who was Arthur’s godfather. The couple married on 13 March 1879, when Princess Louise was 19 and the bride’s family came to England for the occasion travelling on the Maid of Kent under Captain Pittock.

Maid of Kent tied up to Admiralty Pier. The body of George V (1819-1878), the last King of Hanover (1851-1866) was brought across the Channel on the ship for burial at Windsor.

The blind George V (1819-1878), the last King of Hanover (1851-1866), and his daughter Princess Frederica of Hanover (1848- 1926) spent five weeks in Britain in May-June 1876. During the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and against advice, King George involved his country on the side of Austria when Prussia invaded. This eventually led the surrender of the Hanoverian Army on 29 June and Prussia’s formal annexation of Hanover in September forced King George to abdicate. The father and daughter travelled to England on the Samphire, with Captain Frederick Dane (1835-1913) in command. They were met by one of Dover’s two Members of Parliament (1865-1889) Major Alexander George Dickson (1834-1889), on behalf of LCDR. Two years later, on 23 June 1878, the King’s body was brought back to England on the night packet from Calais, the Maid of Kent, under the command of Captain John Whitmore Bennett (1828-1907), for burial in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. A number of Hanoverian dignitaries accompanied the body but as it was 04.00hours when the ship docked at Admiralty Pier, there was no formal welcome. The Dover Express reported that the remains were ‘carried off to Windsor with as much ceremony as Her Majesty’s mails’. The funeral, the following day, more than made up for this.

Franz Joseph I (1848-1916) the Emperor of Austria’s wife, Empress Elisabeth (1837-1898), visited England in April 1876. Following the Seven Week Austro-Prussian War, Franz Joseph was forced to cede the German crown to Prussia but he did retain his Empire. In 1873, under the influence of the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismark (1815-1898), Franz Joseph along with Kaiser Wilhelm I (1871-1888) of Prussia later Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany and Tsar Alexander II (1855-1888) of Russia formed the League of Three Emperors (1873-1887). This was, it was reported, to maintain peace in Europe. Empress Elisabeth had crossed the Channel on the LCDR packet Foam in April 1876, with a large entourage. For the journey, she used the pseudonym the Countess of Palfry to hide her identity even though the entourage included a ‘stable of horses’! It would appear that she had expected to be invited to Windsor by Victoria but the British Queen declined to make such an offer. So the Empress of Austria and her retinue left for Towcester, Northamptonshire where, using the pseudonym Countess Hohenembs, she rented Easton Neston House.

The following month, May 1876, LCDR received a special request that was to be kept as secret as possible. The remains of King Louis-Philippe (1830-1848) of France and his wife Marie-Amélie (1782-1866) of Naples and the bodies of other members of the Orléans family including five of their children, that were buried in St Charles Borromeo Roman Catholic Chapel, Weybridge, were to be removed. The family had moved to England following Louis-Philippe’s abdication on 24 February 1848. Since that time, he and his family had lived at Claremont, Surrey and regularly worshipped at the Weybridge Chapel, where the bodies were buried. In June 1876 the French government agreed to the bodies being reburied at The Royal Chapel of Dreux, Normandy, France, the traditional burial place of members of the House of Orléans.

The cortege left Weybridge for Southampton and the crossing of the Channel to Honfleur, Normandy. For the crossing, the French government had requested that this was to be on a LCDR packet ship under the command of Captain Pittock and the Samphire was chartered for the purpose. Ten coffins plus an urn containing the embalmed heart of Louis-Philippe were placed on the aft part of the ship and draped with black cloth. The British Ensign was flown from the peak halyards and the French Tricolour from the main mast of the Samphire, both at half mast. The LCDR flag, also at half-mast, was flown at the entrance of Southampton Dock until the ship had left the harbour. However, the remains of Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1822-1857), the wife of Prince Louis of Orléans, Duke of Nemours (1814-1896) and the cousin of Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861) stayed at Weybridge. The Queen had refused to allow them to be removed but eventually, in 1979, they were moved to the Royal Chapel of Dreux.

Storms damaged Admiralty Pier in January 1877 and Dover Harbour Board had paid £26,000 to have it repaired. The work was carried out by William Adcock (1840-1907). At Folkestone, SER ships were battered and the repairs were estimated at £2,000. The stormy weather continued and the cliffs between Folkestone and Dover started to give way. SER were forced to close the line while cliff shoring was being undertaken. LCDR helped out by allowing SER passengers to use their train to travel to Dover for the Ostend service. However, as the wet and stormy weather continued sections of the LCDR line between Dover and Canterbury became vulnerable to collapse. An understanding was reached while repairs were undertaken enabling LCDR to divert their packet ships to Folkestone and SER trains to carry the mail for them. This bonhomie between the two companies gave their chairman Watkin, the impetus to make LCDR another offer of amalgamation and went as far at to devise a timetable for talks, sending an appropriately worded Bill to parliament and publicising the possibility.

This caused consternation in Canterbury, which was served by both companies to two separate railway stations, Canterbury East (LCDR) and Canterbury West (SER). In early February 1876 a public meeting was called under the chairmanship of the city’s mayor, William Henry Linom (1820-1888). Primary causes for concern were cuts in services and increases in ticket prices. Several speakers pointed out that as things stood, trains were often overcrowded and ticket prices extortionate between Kent and London except to places where both SER and LCDR had stations. On such lines the competition for passengers was such that there was plenty of room and the fare per mile was cheaper. The same applied, the audience was told, to the carriage of goods, produce and animals.

As for the cross Channel packet fares, a speaker stated that they were kept in check by competition. But that there was a general under capacity on the ships and except for when the Castalia was in operation. The accommodation provided by both companies, except on the Castalia and on all the trains was, at best, worn out! At the end of the meeting, it was proposed by Canterbury banker George Furley (1817-1898) and seconded by bookseller William Bohn, that a committee should be formed. Mayor Linom agreed to chair this and the remit was to observe the decisions made by the Directors of LCDR and SER. On this basis, Linom and his committee were authorised to take any action they saw fit in order to protect the interest of people residing in Canterbury and East Kent. The proposal was unanimously adopted.

Forbes digested the report of the Canterbury meeting, given to him by his employees who had attended and brought it up with Board members prior to the LCDR Annual General Meeting. This was held the following month and there, Board member Major Dickson put forward the SER amalgamation proposition and the shareholders endorsed it. Forbes, as Chairman, acknowledged their wishes adding that if SER offered favourable terms to LCDR, then an amalgamation would take place and neither he nor the Board would stand in the way.

He then added, in essence, that from 1860, when LCDR had first opened the line to Dover the Company has been fighting for its existence against two powerful neighbours, the South Eastern and the London, Brighton, and South Coast railway companies. Further, debt, pressing creditors and doubtful stock issues had wreaked havoc on LCDR but with skilful and careful leadership, he was sure that Company could, in time, become viable in its own right. Therefore, Forbes said, if negotiations were not favourable to LCDR and its shareholders, then the plan should be rejected. A show of hands supported hm.

The negotiations were turbid and as they were drawing to a close Forbes arranged to meet the Canterbury group on their own territory. From the opinions expressed, Forbes became aware of the need for a passage service from north Kent to the Netherlands and northern Europe and that the Stoomvaart Maatschappij Zeeland SS Co (SMZ), known in Britain as the Zeeland Steamship Company, had in 1875, run such a service from Queenborough north Kent. SMZ ‘s Dutch base was Flushing, (Dutch – Vlissingen) in south west Netherlands but that the service had since ceased.

Following the meeting, Forbes team contacted Simon Josephus Jitta (1818-1897) of SMZ and along with Forbes, they went to look at Queenborough. The town and port is on the east side of the River Medway where it enters the Thames Estuary. Back in the late 1850s the Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway Company had built an 8miles 5chains spur from what became the LCDR Strood-Faversham railway line. This was to Sheerness where there was a Royal Naval base and the railway line had opened on 19 July 1860. From that time LCDR had leased the line from the Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway Company for £7,000 per annum, which was just about covered by the receipts from Royal Naval passengers and goods.

Two miles south of Sheerness, was/is Queenborough which, at the time Forbes and his team arrived, was in a very poor state. Historically, the town had thrived on trade from it’s position between London and the North Sea, but improved navigation meant that the town and it’s marine facilities were bypassed. In the 1850s Queenborough was bankrupt so parliament had put the town into the hands of Trustees. Forbes noted the location had possibilities and he made the Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway Company an offer for their railway line. By the summer of 1876 the two companies had merged and LCDR were building the half-a-mile long Queenborough Pier. This was on the Sheerness side of Queenborough railway station out into the River Medway close to its junction with the River Swale. The Company then laid a railway connection from the down-side of the Sittingbourne & Sheerness Railway line and along the Pier. They also built a purpose designed quay adjacent to the Pier and after negotiations with Jitta of SMZ that Company started a new service between Queenborough and Flushing.

When SMZ had started their original service, on 26 July 1875, they did so with two former Confederate blockade runners left over from the American Civil War (1861 to 1865). These they named Stad Middelburg and the sister ship, Stad Vlissingen. The two ships had been built by Quiggin & Jack of Liverpool as the Northern and Southern, respectively. Originally, SMZ had run a nightly service except on Sundays with the two steam ships and following discussion with LCDR, SMZ reintroduced the service and ships until better and more ships could be afforded.

The new service was advertised and the media took notice but just as the new passage service was taking off, the crank axle of the Queenborough-Flushing boat express engine broke while travelling at high speed. This was about six miles from Sittingbourne and caused the driving wheels to leave the line and the train to travel nearly a mile, passing over a bridge, before the driver could bring it to a halt. Although the engine was considerably damaged and the SMZ ship was delayed for three hours until the passengers arrived, no one was hurt. It took two days to repair and re-open the line but the event was well covered in the national papers and commented upon by SER. In the meantime, Jitta had applied to the Dutch government for a Holland – England packet contract and with the backing of Forbes to provide the rail service, SMZ won it!

For much of the 19th century Dover had called for the much needed Harbour of Refuge on the East coast of Kent and for it to be sited at Dover. This had been promised and Admiralty Pier had been built to provide the western arm. However, government money had not been forthcoming to complete the project and this had not been helped by Watkin along with massive support from senior members of his political party, the Liberals and those powerful in the Folkestone/Hythe area putting pressure on the government to build the Harbour of Refuge at Folkestone. Back in 1873, Forbes had stood for a parliamentary election for the Liberal Party in Dover on the premise that he planned to turn Dover into one of the major passenger ports in Europe and his aim, if elected, was to get the Harbour of Refuge that the town had long been calling for. However, the voters of Dover declined to make him their MP, instead preferring a Tory.

Earl Granville, Lord Warden and Chairman of Dover Harbour Board who was champion for a Harbour of Refuge to be sited at Dover.

Albeit, in May 1876 in the House of Lords, the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, the Liberal Earl of Granville, had again put forward the need for a Harbour of Refuge and emphasised that it should be at Dover. He also stated that since 1860, when LCDR had first provided a cross Channel service from Dover the number of passengers using the port had increased and this included members of the Royal family. Granville went on to say that the number of passengers carried between Dover and the ports of Calais and Ostend continued to increase and made reference to passenger figures for that year to May. The figures for the full year were embarkation for Calais 102,121 and for Ostend 18,142. Landed from Calais 99,728 from Ostend 19,137, making the total passenger traffic between Dover and Calais 201,849 and between Dover and Ostend 37,279 and the total passenger traffic for the port 239,128. Thus, he said, there was a need for a specially constructed Water Station, covered space to accommodate cross Channel steamers and a connection from the shore over which the trains would pass to get alongside the cross-Channel ships. Granville finished by saying that both railway companies along with Belgium Marine, through Dover Harbour Board (DHB), had offered to contribute a total of £200,000 towards such a facility but the government had turned down the offer. The government had told DHB that this was because they were planning to build a Harbour of Refuge but no evidence of this was forthcoming.

In response, Granville was told that a water station was about to be built at Dover by a private sector company. In 1875, Hugh Aldersley Egerton (1834-1913) of Banbury had filed a patent for a Channel Ferry that, he said, would revolutionise the cross-Channel industry between Dover and Calais. He had designed a triple-hull ship 600-feet long, with 228-feet beam and estimated to cost £125,000. The ship, he said, would have the capacity to carry ten complete trains, with 2,000 passengers and 500 tons of baggage. The trial of a model of the vessel took place on the Brent Reservoir between Hendon and Wembley Park, London. This was successful and was followed by a publicity trial on the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London. The following year, just before Granville made his speech, Egerton filed a patent application for the ‘Improvements in the construction of floating piers and other analogous structures for embarking or disembarking passengers, animals or merchandise,’ specifically with Dover in mind and included a water station. However, neither Egerton’s giant steamship nor the water station were built and he left for France. There Egerton became an adviser to the French government on cross-Channel shipping improvement.

Opening of the SER Folkstone-Dover Line after a cliff fall in 1877. Watkin, the Chairman of LCDR is wearing the Cossack style hat. Dover Library

A severe storm hit the south east corner of Kent in January 1877, washing away the foot of the cliff at the eastern end of the Martello Tunnel, on the SER line between Dover and Folkestone. This had brought down some 60,000tons of the chalk cliff, killed three workers and completely blocking the line. Forbes reacted by offering the use of the whole of the LCDR railway lines to Watkin, writing, ‘We are partners in the Continental Agreement, take your mails over our railway.’ For the following two months, until SER repaired the line, their trains carrying mails for Belgium, went from London to Beckenham on the SER line and from there on they used the LCDR line to Dover. During this time there were rumours that SER had no intention of reopening the Folkestone-Dover line and Watkin was of the opinion the rumour had originated with Forbes. When the SER line was finally repaired, Watkin organised a grand re-opening and arrived on a Cudworths 2-4-0 Class E locomotive with a stovepipe chimney and wearing a Cossack style hat. At the time Russia was about to be embroiled in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and Watkin drew analogies from the two countries relationship and the relationship between SER and LCDR.

Nationally, the media and passengers were more interested in the accommodation on board cross Channel ships than the hat Watkin was wearing. Although SER was at the brunt of most of the complaints, LCDR also received a great deal of criticism particulary in comparison with the furnishing on the Bessemer and Castalia. In the summer of 1878 a major exhibition was to be staged in Paris and in consequence this increased the SER impetus to join forces with LCDR but Forbes and the Board were far from happy with the terms offered. Nonetheless, both companies started working together with a view to amalgamation and that included meeting the demands of the possible increase in the number of passengers crossing the Channel to attend the 1878 Paris Exhibition.

Early in 1877, an iron twin-hulled paddle steamer with engines by Black, Hawthorn & Co of Gateshead and designed and built by Andrew Leslie & Co of Hebburn-on-Tyne was launched. She was the direct successor to the Castalia and although the basic design was in accordance with the Captain William Dicey patent for that ship (see Packets part 4), the company that had ordered her, English Channel Steam Ship Company, had demanded a number of modifications. They named their new ship, Empress and she was launched on 14 April 1877. By that time, however, the English Channel Steam Ship Company was insolvent but having previously informed the English Channel Transit Company, Andrew Leslie & Co continued on their own account. She was estimated, at that time to cost £90,000.

The Empress was 302feet in length and 65feet6inches in width with a tonnage of 1,925gross. Her engines were 4 diagonal-acting 150horsepower, one on either side of the twin hulls while her draft was only 6foot 6inches. This would enable her to enter ports such as Calais harbour at low tide so the LCDR were interested. Although of the same principle as the Castalia, each hull was a ship within itself and through the wider gap between the two stems than that of the Castalia, the water rushed through with the velocity of a mill race. This gave the paddle wheels, which were amid-ships, a stronger bite. The water escaping at the stern added momentum to the speed of the ship without the rolling, pitching and tossing experienced on other ships at the time. Forbes was impressed.

So impressed were LCDR that Forbes, members of the LCDR board and Captain Pittock went to see a trial, along the coast out of Newcastle to Coquet Island a distance of approximately 22½ statute miles. A mile and a half longer than the direct route from Dover to Calais. With the average speed 14.48knots an hour, the trip took an hour and twenty minutes. Further, the ship could accommodate 1,000 passengers and the passenger accommodation was luxurious. By this time, the finances of LCDR were starting to look up and with the possible increase in bookings due to the Paris Exhibition, the LCDR contingent agreed to pay the full asking price! Renaming their new acquisition Calais-Douvres she was the first new ship that LCDR had purchased since the Company had first set up a cross-Channel packet service at Dover seventeen years before!

Captain Pittock and his crew brought the Calais-Douvres to Dover, arriving on 5 May 1878 having taken 24 hours from Newcastle. The journey was uneventful and the trial run to Calais was on 9 May. This proved highly satisfactory with an average speed of 14 knots. However, the Calais-Douvres had used up so much coal that she required bunkering, which took 1½hours. Two days later she made her publicity trip with the LCDR Board members headed by Forbes, representatives of SER, Nord of France Railway Company, Dover Harbour Board and dignitaries that included Richard Dickeson (1823-1900) the Mayor of Dover and councillors.

While in France, the assembled LCDR Board and guests were invited to look at the Calais Chamber of Commerce’s proposed plans for a new Calais harbour. They, like Dover, had great ideas but lacked the finance. Nonetheless, the French Government had set aside some 50million francs for national harbours to be created at Boulogne, Calais, Dieppe, Dunkerque and Le Havre. Indeed, on 9 May 1878, the first stone for a French national Harbour of Refuge had been laid at Boulogne. Originally the River Aa fed Calais harbour and although sand deposits had moved the mouth of the river north this had created a large lagoon on the flat seashore of the town. This natural reservoir filled at each tide and at other times was fed by local streams, which kept a channel sufficiently open to allow small vessels to enter.

The Dover-Calais and Folkestone–Boulogne mail packet contracts had come up for renewal at the beginning of 1878, as both LCDR and SER had terminated them early. This was a joint decision and the primarily reason had been in the hope of gaining better terms. On 13 April, Forbes was asked by Henry Cuthbert (1829-1927) the Postmaster General (1877-1878) to specify LCDR Company’s requirements though SER were not approached. Forbes responded by asking for a number of increases and concessions including raising LCDR’s subsidy from £6,000 to £8,000 a year and for the transportation of special mail, particularly large or/and valuable packages to be paid between £20 and £40 each. Without being asked by Cuthbert, SER made the same demands. Cuthbert responded by terminating both contracts and publishing adverts for applications. Only LCDR and SER applied and both companies specified the terms that Forbes had outlined. This fait accompli the Lords of the Treasury reluctantly accepted on 22 April but stated that under the House of Commons Standing Orders of 13 July 1869, they were not going to specify the length of time the contracts were to run.

Out of the blue on 5 June 1878, the contracts were fully ratified but with stipulations applicable to both Companies. These were to improve the railway lines, engines and carriages between London and the Channel ports and for new packet ships to be purchased. During parliamentary discussions Major Dickson, Dover’s Member of Parliament and LCDR Board member, said that as far as LCDR were concerned, they had asked for a larger subsidy due to the increase in the amount of mail that had to be carried and the state of Calais harbour. The latter could not accommodate single keel ships of larger size than those already in operation until their new Harbour of Refuge was completed. It was for this reason, Dickeson told the Commons, that the Company had purchased the shallow draft Calais-Douvres, at great expense.

The previous year the other of Dover’s two Conservative MPs, Charles Kaye Freshfield (1865-1868 & 1874-1885) had reiterated the case for a Harbour of Refuge and reminded parliament that Granville had been promised the building of a Water Station at Dover in 1876, but this had not been forthcoming. He finished by pointing out that such a harbour was of national importance, saying ‘that the Strait of Dover, through which a large proportion of the nations commerce and navy had to pass and where the country’s ships of war could best wait in ambush should there be a need, should be completed.’ (Hansard 01.06.1877). However, on 26 March 1878, the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) First Earl of Beaconsfeld, had made a statement in the Lords that was so sarcastic it was generally seen that the Harbour of Refuge of Dover would not happen while he was in power. Disraeli’s disparaging remarks plus the building of the French Harbours of Refuge so infuriated the media that the Times of 7 September 1878 wrote, ‘The English experience has been disastrous, it is now nearly thirty years since we set about forming a harbour of refuge at Dover and we lost no time in constructing fortifications to defend it, but the harbour itself has been reduced to the Admiralty Pier, where the sea in one night destroys the work of a year … The Strait of Dover is about the worse sea crossing in the world …’

Forbes recognised that LCDR did need new packets ships as well as engines, carriages, goods vans, freight wagons and infrastructure etc, but having purchased the Calais-Douvres, he did not have the money. Albeit, the Queenborough-Flushing crossing did have possibilities for upgrading. Along with Jitta, the chairman of SMZ, they met with the appropriate personnel within the Dutch government and negotiated a deal whereby the Dutch government agreed to refinance SMZ in order for that company to purchase two new ships at a low interest rate. These were, the Prinses Elisabeth and the Prinses Marie both registered in Amsterdam and ordered from the Fairfield Shipping Company of Glasgow. They were 3,000tons with two 200 horsepower compound diagonal engines that had a low pressure cylinder diameter of 106 inches that gave them a speed of 17.2knots. The boilers were fore and aft of the engines and the ships each had two funnels. The Prinses Elisabeth and the Prinses Marie were the largest, fastest and most comfortable of the cross-Channel steamers of the time and came on service in March and April 1878.

On the morning of 17 May the Crown Prince of Germany and his entourage arrived at Dover on the Samphire and in the afternoon the Prince and Princess of Wales came across on the Calais-Douvres having travelled from Paris. Dignitaries, military bands and a gun salute from the Castle gave a stately welcome to both Royal parties. The Crown Prince and his entourage had lunch at the Lord Warden Hotel before going on to London but the Prince and Princess of Wales went straight to Windsor Castle to a State banquet hosted by the Queen. Both parties travelled on LCDR trains. Unfortunately for LCDR, before the week was out the Petrel broke down on her way to Calais with passengers and mails on board. The Maid of Kent took both and continued the crossing while the Samphire took the Petrel in tow back to Dover.

For the Whitsun Bank Holiday at the end of May 1878, LCDR provided a special excursion from London and stations along the railway line to Dover and then to Calais and back on the Calais-Douvres. Although the weather was bad, between 500 and 600 passengers took up the offer and were delighted particularly with the comfort the ship offered. For those looking for a longer holiday on the Continent the Prinses Marie and Prinses Elisabeth out of Queenborough, to Flushing proved the most popular. On Thursday 30 May the Calais-Douvres commenced her daily service and 242 passengers made the crossing to attend the Paris Exhibition. Unfortunately, just before leaving Dover, one of her cylinders failed so the crossing had to be made on three-quarters of her full power.

The Paris Exhibition ran between 1 May and 10 November 1878, to celebrate the recovery of France following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, when Emperor Napoleon III (1852-1870) was forced to abdicate. Together with SER, LCDR marketed special tickets at the reduced rate of 31shillings 6pence single and 47shillings return between London and Paris. For passengers living outside London, at the instigation of the Prince of Wales, there were special second class concessionary rates. For instance, between Bradford and Paris the single fare was 36shillings 6pence and cheaper for parties of 20persons. In Southwark, London, 18-year-old Thomas Cook decided to cash-in on the interest and he advertised single tickets at 30shillings first class and 25shillings second class, with return tickets at a further discount. He also advertised hotel accommodation in Paris for 25shillings a week.

Cook had contacted printer Edward Smith of Finsbury making out that he was the son of Thomas Cook (1808-1892) the travel entrepreneur and had ordered both advertising pamphlets and also tickets paying the printer 10shillings. Young Cook then sent the pamphlets to newspapers, one of which landed on the desk of William Hatton, the proprietor of the Bradford Chronicle and Mail. He published the offers and William Bonsor of Bradford deciding to take up the offer, sending the young Thomas Cook a postal order for the requisite amount and asked for details of the hotel accommodation. He received what he believed to be genuine travel and entrance tickets but not the details of the hotel accommodation. Bonsor therefore contacted the real Thomas Cook travel company thanking them for the tickets but stating that he still had not received the asked for hotel details. This brought the scam to light and the young Thomas Cook was arrested, tried and sent to prison.

Prime Minister Disraeli, on 10 June 1878, travelled on the Maid of Kent with Captain Pittock in charge, to Calais. From there he travelled by train to Berlin, spending the night at Prisse Palace, Belgium. The reason for the visit dated back to July 1875, when the former Prime Minister (1868-1874), William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898) brought Beaconsfield’s attention to the atrocities being committed by the Turkish Ottoman Empire in Bulgaria and Herzegovina following an uprising. At the time the Ottoman Empire was a British ally and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) was despatched to the Constantinople Conference (December 1872-January 1873) to seek agreement on reforms in Bulgaria and Herzegovina. These were rejected and the result was the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), that Watkin had referred to when he reopened the Folkestone-Dover line in early 1877 wearing a Cossack style hat. As a result of the War the Russian forces freed most of the Balkans from Turkish rule. In January 1878 the British Fleet were sent to Constantinople while the Army was preparing for any repercussions a result of the War.

The British were concerned that the Russians, as masters of the Balkans, would threaten their power in the Mediterranean – a vital route to India. For LCDR, Forbes was concerned that hostilities would directly affect the transportation of Indian Mails. The Peace Treaty of St Stefano between the Ottoman Empire and Russia was signed on 3 March 1878 and included the provision to create an independent Bulgarian principality. This made it the largest country in the Balkans and was a concern. Other territories were ceded to Russia and therefore rejected by a number of European powers, including Britain. It was to the Berlin Congress, held in June and July that Beaconsfield, along with Salisbury, were travelling in the hope of a settlement. According to British observers, the Congress ended in a diplomatic victory by Beaconsfield as Russia allowed Turkey to recover most of its European provinces. Austria was given a protectorate over Bosnia and Britain was given Cyprus. The Treaty of Berlin was signed on 13 July 1878 and on his return Lord Beaconsfield and Lord Salisbury arrived in Dover on the Calais-Douvres to a tumultuous welcome. This included royalty and dignitaries from across the country. Beaconsfield Avenue and Salisbury Road, Dover, were later named in honour of the two men.

Monday 5 August 1878, was a national public holiday and the weather was fine. 811 people travelled from Dover to London to spend the day in the capital while some 2,203 travelled in the opposite direction to spend the day by the sea at Dover. In the latter part of the 19th century and early twentieth century Dover became a popular tourist resort and Dover Corporation were doing everything possible to foster that image. Two days before, on the Saturday 3,406 passengers left London for a holiday on the Continent with 495 crossing the Channel on the Calais-Douvres, not so many travelled on the other Dover – Calais ships nor the SER ships out of Folkestone with most preferring the Queenborough and Flushing route. This was hardly surprising for not only were the ships better, but the length of Queenborough Pier ensured that the quay could be used at all states of the tide. Further, the station was sited on the Pier close by, so passengers did not have far to walk. LCDR had installed turntables at the Pier end so that luggage carriages as well as freight wagons could be positioned for easy loading /unloading. SMZ had installed cranes at the Pierhead to make all these operations quicker and easier.

Pickpockets had long been a scourge of the packet ships, as well as railway stations and trains, and on that particular weekend a gang had travelled down from London to target passengers on the Calais-Douvres. As a great favourite with day trippers the ship was expected to be crowded and following consumption of alcohol, the trippers were unlikely to notice they were victims until much later. Further, as the Calais-Douvres was heavy on fuel and in order to reduce consumption her speed was kept down, the longer duration of the crossing worked in favour of the pickpockets. When over the next few days, the extent of the pickpocketing came to light, the victims held LCDR morally responsible for the thefts and the Company came in for much criticism in the national newspapers.

LCDR already had their own police force that had been in existence in 1858, when the company operated under the name of East Kent Railway Company (See LCDR part I). Records of the LCDR earliest trial, still in existence, that took place at the Old Bailey, London, on 9 April 1866. This was the prosecution of Alfred Martin, age 38, who worked as a car-man who had stolen five dead fish. LCDR Police Inspector James Tyrell handled the case and when questioned, Martin told the Inspector that all he meant to do was take the fish, which were soles, home to his wife. Although Tyrell had a great deal of sympathy for the man, he was still obliged to bring the case. Martin was found guilty and lost his job. (Thanks are due to British Transport Police History Group for this information). Following the number of thefts on the Calais-Douvres over that August Bank Holiday weekend, LCDR recruited more policemen and increased the number travelling on their ships.

As the Calais-Douvres was heavy on coal, using about 40tons a day, and because of the reduced number of passengers travelling on the packets during the winter, she was taken out of service. This led to crew lay off including Captain Bennett. Just before midnight on 4 November 1878, about 8miles southwest off the South Foreland the German packet ship Pommerania of the Hamburg-American Steamship Company, was in collision with the Moel Eilian sailing vessel of Carnarvon. The 3,338ton Pommerania, enroute from New York to Hamburg, sank in 20minutes with a loss of some 50 lives. The night was foggy with drizzling rain and a moderate North North Easterly wind.

Captain John Whitmore Bennett (1828-1907) of the London Chatham and Dover Railway Company. Hollingsbee Collection

The Glengarry steamship from Middlesborough went to the rescue and the manifest showed that there were 151 passengers on board the Pommerania and a crew of 111. The Glengarry rescued 109 passengers and 63 crew members, all of whom were brought to Dover on the harbour tug Granville. Captain Bennett left his home in the Pier District and rowed out, with some of his crew that had also been laid off. They helped to bring the Moel Eilian into Dover. She was described as having her bow stoved in and the forward compartment full of water. In Dover, Captain Bennett was praised for and people recounted the Samphire disaster of 1865 (see Packet Service part IV) and how the Admiralty Court had made Captain Bennett the scapegoat for their own failure to implement safety regulations that would distinguish ships under sail from those under steam at night. They also recounted how, that same year, Captain Bennett, in charge of the Maid of Kent’s night service, through supreme seamanship had saved the disabled steam packet from drifting helplessly onto the Goodwin Sands. It was a long time after the accident that such regulations were introduced.

January 1879 saw the annual series of winter heavy gales that afflict the Dover Strait but this time the temperatures were generally so cold that there were reports of ice floes down the Thames. One morning the Granville dock gates were frozen and could not be opened thus the LCDR packet ships within were unable to leave. Eventually, under the supervision of the Harbour Master Richard Iron (1818-1883) a stout hawser was made fast with blocks and pulleys and operated by some 30men and gradually the gates did open. Nine hours late the night packet ship, Maid of Kent, to Calais was able to get underway.

The news from Calais was that once the inclement weather had abated, that work was to start on a Harbour of Refuge there. If it did go ahead, it would include major construction work that would make Calais a viable international shipping port! During the previous autumn the French Minister of Finance, Jean-Baptiste-Léon Say (1826-1896), and the Minister of Public Works Charles Louis de Saulces de Freycinet (1828-1923), had undertaken a tour through the departments of Pas de Calais and Nord. There they looked at ports and infrastructure and listened to the ideas of public bodies such as the Calais Chamber of Commerce. In Calais a careful survey had been undertaken on 10 September and the government surveyors had come up with a grand scheme. The communiqué stated that the scheme would have to go through the French Chamber of Deputies and the Senate so could be subjected to severe pruning. However, as Léon Gambetta (1838-1882) had been elected President of the Chamber of Deputies the letter finished by saying that the Calais Chamber of Commerce was sure that he would be receptive to Calais needs.

In February 1879, Empress Elisabeth of Austria again crossed the Channel and again incognito. She made the crossing, with her entourage and stable of horses, on the Maid of Kent and was on her way to Ireland. There, totally open as to whom she was, on 23 March she received a communiqué from home and was obliged to return immediately. This she did again crossing from Dover to Calais and then by rail to Vienna. The emergency that had summoned her were the negotiations taking place between the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires. The result of which was the Dual Alliance of 7 October 1879, when the two Empires promised to support each other if Russia chose to attack either. The two Empires also agreed that in the case of aggression by any other or between any other powers they would remain neutral.

This political arrangement was the work of German Chancellor Bismark and he surmised that Russia would not dare to wage war against both Empires while the agreement would prevent Germany becoming isolated. The Alliance was expanded in 1882 when Italy joined the two nations but the potential of threat of the Triple Alliance led, in 1902, to the formation of the Triple Entente. This was between the United Kingdom, France and Russia and many historians believed it was the primary event leading to World War I (1914-1918). As far the Empress Elisabeth was concerned as she travelled home in 1879, the Dual Alliance could promote German nationalism and destroy the Austrian Empire.

The Calais harbour project was given the go ahead but its potential for LCDR, once complete, annoyed Watkin. This was compounded by the Liberal Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, the Earl of Granville who, in the Lords, was constantly putting forward the case for Dover to become a Harbour of Refuge and because of this was considering leaving the Party. At the SER shareholders meeting in January 1880 meeting, in essence, he said that back in 1836 the Parliament Select Committee had favoured Hythe Bay for the Harbour of Refuge and this was the main reason that the Company had paid £18,000 for Folkestone harbour and make it their main port for Continental services. Even though the Company knew that it would be expensive and foolhardy due to geological problems caused by the proximity of the cliffs to the sea, pressure had been put on the Company to take the line to Dover. This work, paid for by the Company, had given the impetus for Dover to put the case forward for a Harbour of Refuge to be there. Nonetheless, the 1843 Parliamentary National Harbour of Refuge inquiry stated that Folkestone was the favourite.

Indeed, Watkin reminded his audience, the eminent civil engineer William Cubitt (1785–1861), had given evidence on behalf of SER, pointing out the vulnerability of the cliffs between Folkestone and Dover and described the work carried out by the Company to make Folkestone Harbour the pride of the Channel coast. Since that time, Watkin said, Dover had used every opportunity to push the Harbour of Refuge argument in their favour and the western arm of the Harbour of Refuge, Admiralty Pier, was built at Dover. Luckily for Folkestone the Tories, which could not normally be trusted, under Prime Minister Disraeli had shelved the Harbour of Refuge idea at Dover. However, if the Liberals came to power the Lord Warden, Lord Granville would ensure that the situation would change in favour of Dover.

Watkin then turned his audience’s attention on to LCDR, saying that they had opened their railway line to Dover as they planned to use the planned Harbour of Refuge as a Continental freight terminal – or so they said. In reality, they immediately bought ships for the cross Channel ships passage and their shrewd General Manager Forbes, quietly put in a bid for the packet contract between Dover and Calais. Why SER had allowed LCDR to win it, was beyond his comprehension, Watkin’s said, but at that time he was not the Chairman of SER.

Nonetheless, Watkin continued, SER had been fair to LCDR especially over the Continental Agreement whereby all Continental traffic receipts were pooled and divided between the two Companies. Forbes in his usual underhanded way, had opened a cross Channel service between Queenborough and Flushing and subsequently won the packet contacts to carry mail to and from the Netherlands! None of the profits that LCDR make from their rail service between London and Queenborough are included in their contributions to the Continental Agreement and in consequence SER was losing some £15,000 a year. Therefore, Watkin said, SER had two courses of action open to them. The first was litigation, which would be expensive. Alternatively, SER could set up a rival Continental service from Chatham where two of their existing ships would be based and for the Folkestone – Boulogne service, order possibly four new ships!

The shareholders voted for the second option and during the questions, Watkin confirmed that SER were occasionally running to Calais but, he added with delight, that LCDR were not allowed to berth any of their ships in Boulogne. This, he said, gave SER the monopoly of the shortest cross Channel route. On reading the press coverage of Watkin’s speech, Forbes wrote to him and the national newspapers informing both that SMZ operated the passage ships out of Queenborough not LCDR and therefore revenues earned by LCDR were not part of the Continental Agreement. A number of other writers pointed out that the Dover-Calais route was the shortest. In April 1880, the Liberals returned to power and the Earl of Granville, Dover Harbour Board, and Forbes with other interested parties, exerted as much pressure on the government as they could muster for a Harbour of Refuge to be built at Dover.

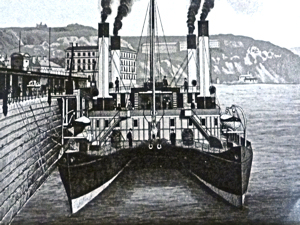

La France with the Breeze, Calais-Douvres and the Wave paddle steamers in Wellington Dock c1880-1890. Dover Library

That month, Queen Victoria, for the first time, used the LCDR Queenborough quay when she returned from Germany. In Flushing the Queen, her youngest child Princess Beatrice (1857-1944) and their entourage had boarded the Royal Yacht (1855-1900), Victoria and Albert II. On arrival at Queenborough, they travelled by an LCDR train to Windsor. Six months later, on 16 November 1880,General Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts (1832-1914), disembarked from the La France at Admiralty Pier to a tumultuous welcome that include both national and local dignitaries. Roberts had fought in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 where he was awarded the Victoria Cross and went on to have a successful military career rewarded by promotions.

In September 1879 Roberts was sent to Kabul, Afghanistan to seek retribution for the assassination of Sir Louis Cavagnari (1841-1879) and his envoy on 3 September 1879. Cavagnari had signed the Treaty of Gandamak with Emir Mohammad Yaqub Khan (1849-1923) in May, which relinquished the control of Afghanistan foreign affairs to the British Empire. It also brought an end to the Second Anglo–Afghan War (1878-1880) between the British Raj and Emirate of Afghanistan. Roberts led the invasion party of 10,000 troops and on 22 July 1880 Abdur Rahman Khan (c1840-1901), who held the position of Emir until his death in 1901, replaced Mohammad Khan.

For well over a century Dover entrepreneurs had earned a livelihood by forwarding parcels, samples and general freight to Continental buyers as well as receiving and forwarding to British addresses, similar packages from Continental manufacturers. This two-way transit of goods was on the increase as innovation had speeded up production. As the British Empire expanded, the manufacturers were looking at these new markets and transport was developing rapidly for the speedier handling of this traffic. In 1880 the General Post Office decided to set up a freight forwarding department, using their packet contracts to ensure fast delivery with the Continent. To tie in with this, LCDR rescheduled the night mail service from London to depart 15 minutes earlier so that the packet ship carrying the night mails to Calais could also leave Dover earlier. In Calais, on transferring the mail, the French mail train left and the mails arrived in Paris in time for delivery by the first post.

The weather for the Whitsuntide Bank Holiday weekend in 1880 was sunny and breezy and on the Monday LCDR offered a special return trip to Calais. This was on the luxurious twin hulled Calais-Douvres and was taken up by 1,200 passengers. From then the Company saw the number of passengers regularly travelling on the to Calais-Douvres being maintained and therefore decided to run her at full speed. The number of passengers increased such that by mid summer the decision was taken to permanently place the ship on the packet service. At the same time, they joined the Calais-Douvres service with the mail express leaving Victoria, London, at 07.40hours, five days a week and the passengers referred to the service as the LCDR Continental service!

At Folkestone, the SER were preparing for the arrival of the two of the four new ships Watkin had promised. They were the Albert Victor and the Louise Dagmar and they were the largest paddle ships to work the cross Channel passage at that time. Built by Samuda Brothers of Poplar, they were both 250feet long 29.2feet beam, 14.3feet deep and with a gross tonnage of 782tons. They had oscillating engines of 2,800ihp made by John Penn and the Albert Victor made 18.58knots over six runs. Both ships were also firsts in that they had steel hulls. Within a year the Duchess of Edinburgh arrived at Folkestone followed shortly after by the Mary Beatrice. The latter was similar to the Albert Victor and Louise Dagmar but 5-feet longer.

Forbes, besides maintaining a working relationship with the Dutch-Rhenish Railway Company, had been appointed the Chairman of the Metropolitan District Railway in 1872. At that time it was in an equally bad financial state as the LCDR when he took over the Company. By 1880, both companies were looking up and that year Forbes was appointed a director of the Lion Insurance Company. This had been established as the Anglo-French Fire Insurance Company Ltd in London and Paris in 1879 and was formed to take over the portfolios of six or seven French offices in Alsace-Lorraine. The company was primarily involved in fire insurance and therefore changed its name to the Lion Fire Insurance Company Ltd. In 1880 it was renamed the Lion Insurance Company Ltd and that year a sister company, the Lion Life Insurance Company Ltd, was established. Both companies provided cover for LCDR rail and shipping operations. In 1888, the French arm of the company was liquidated and on 1 January 1902, it was acquired by the Yorkshire Insurance Company Ltd and was dissolved in 1913. The Yorkshire Insurance Company Ltd became part of the General Accident Fire and Life Assurance Corporation Ltd in 1967.

The insurance company that Forbes dealt with the pay outs following petty thefts and training LCDR police officers. The specialised training was introduced following the summer of 1880, when the number of thefts increased. The London gangs tended to target SER passengers, including those alighting at their Dover Town Station to make their way over to Admiralty Pier for the Belgium ferries. Nonetheless, both LCDR and Belgium Marine ships were also being hit but of the three shipping companies, LCDR had the least problem with theft. As the SER thefts had occurred while passengers were crossing from the Town Station to the Belgium Marine ships, they became within the jurisdiction of Dover Borough police force, Superintendent Thomas Osborn Sanders (1835-1903) called a meeting.

Those attending included senior personnel from SER, LCDR and Belgium Marine, their senior police officers and representatives from the Lion Insurance Company. Since the Great Bullion Robbery of May 1855, SER had ensured a large police presence on their trains and ships and so they outnumbered the joint representatives of LCDR and Belgium Marine attending. Superintendent Sanders told the meeting that following the spate of thefts on the Calais-Douvres in 1878, LCDR had put plain clothes policemen on board their ships as well as uniformed constables. The plain clothes officers and astute passengers, without being asked to do so, made a note of the bank note serial numbers which they carried. If they used them in transactions on board the ships or were stolen during the crossing the appropriate banking authorities were informed of the notes serial numbers. By taking such a course of action, some gang members had been picked up and that was why less pick-pocketing took place on LCDR ships.

Superintendent Sanders went on to say that organised thieving rackets were taking place on other packet/shipping companies as well as on the various railways that made up the British network. For this reason, all the police forces were working together with Scotland Yard to try to put a stop to these rackets using methods similar to those used on LCDR packet ships. To co-ordinate the campaign, a special unit had been set up by Scotland Yard and could be contacted directly.

On 19 January 1881, a severe storm lifted large flagstones, weighing about a ton and a half each that formed the then 250 yard promenade on Admiralty Pier. In some places, the solid concrete base on which they were laid was also lifted. As in 1877, Adcock was called in to make the repairs but due to the time taken passengers boarding the LCDR packets complained of the work getting in their way. Initially, such complaints only occasionally appeared in the national newspapers but very quickly the complaints escalated and LCDR began to wonder if they were emanating from elsewhere.

The winter storms, however, did not let up and at 02.30hours on 8 February the Breeze, carrying the French night mail, was endeavouring to leave Calais harbour against strong winds. Before making it to the open sea, she became stuck on the harbour bar and remained in that position for two hours before the captain and crew managed to get her off. By that time considerable damage had been done and the ship was deemed not seaworthy for the general public. Using the cross Channel submarine telegraph, Dover was informed and eventually the Wave arrived. She returned to Dover with the passengers, mail and the Breeze in tow at 11.00hours on 9 February. The number of shipping casualties in the Channel during those 24hours was unusually high and many were serious.